Abstract

Metal strain gauges have been employed for strain and stress measurements for more than 50 years, given their low cost and ease of implementation. However, they face challenges in achieving high sensitivity and miniaturization from the millimeter to the micrometer scale due to their small gauge factor (≃ 2) and low electrical resistivity (≤ 1.1 μΩ∙m). Here, we discovered that metal–insulator nanogranular films can become a novel high-sensitive and micro-scale strain gauge. A Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular film, which comprises metal Co nanogranules and an insulating MgF2 matrix, exhibited a gauge factor 5 times larger and an electrical resistivity 107 times higher than those of practical metal strain gauges. These superior properties originate from the electronic tunneling conduction between the nanogranules, as opposed to the metallic conduction occurring in metal strain gauges. The large gauge factor of nanogranular films is given by the deformation in the intergranular spacing, which causes the modulation of electron tunneling, and thus, the resistivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1938, Simons and Ruge invented the resistance strain gauge, which modifies its electrical resistance in response to mechanical deformation. For over half a century, resistance strain gauges have been used for strain and stress measurements in solid objects. Metal strain gauges, prepared using Cu–Ni and Ni–Cr alloys, have been widely used owing to their low cost and ease of fabrication. Their sensitivities are evaluated using gauge factor (GF), which is the strain coefficient of the electrical resistance. However, they are not suitable for realizing highly sensitive and micro-scale miniaturized devices due to their small GF (≃ 2)1,2 and low electrical resistivity (ρ0 ≤ 1.1 µΩ∙m, ρ0 is the zero-strain electrical resistivity)2,3.

Metal–insulator nanogranular films (nanogranular films), which are composed of magnetic metal nanogranules dispersed in an insulating ceramic matrix, are known to exhibit unique magnetic4,5,6, dielectric7, magneto-electric8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17, and magneto-optic18,19,20,21,22 properties originating from their nanostructural features and nanogranule content23. For example, nanogranular films exhibit high-frequency soft magnetic properties owing to their high electrical resistivity, saturation magnetization, and anisotropic magnetic field4,5,6, and giant Faraday rotation attributed to the enhanced orbital magnetic moment of the nanogranules20,21. Moreover, they exhibit the conventional tunnel magnetoresistance effect9,10,11,12,13,15 as well as the novel tunnel-type magneto-dielectric14,15,16,17 and magneto-optic22 effects. These tunnel-type phenomena originate from spin-dependent electronic transport via quantum tunneling between the nanogranules through an insulating matrix with sub-nanometer-scale intergranular spacing (s)14,24,25 (Fig. 1a). Nanogranular films have practical advantages such as ease of production and good reproducibility11. They are suitable for microscale miniaturization and power saving applications because of their high electrical resistivity2,11.

Schematic structure of nanogranular films and the electronic conduction in the film with bending. (a) Schematic of a bent nanogranular film with nanometer-sized granules dispersed in an insulating matrix. The electronic transport in nanogranular films is caused by the electron tunneling between nanogranules through the matrix. The intergranular matrix functions as a tunnel barrier. When the film is bent upward, a compressive strain is induced in the film, whereas when it is bent downward, a tensile strain is induced. (b) Model for the deformation in the nanostructure of the nanogranular films when the strain ε < 0, ε = 0, and ε > 0. ε is applied in the current flow direction. d and s are the nanogranular diameter and intergranular spacing, respectively. d0 and s0 are the nanogranular diameter and intergranular spacing when ε = 0.

Some fundamental questions related to their inherent properties remain. First, what is the effect of applying a mechanical pressure to nanogranular films? Further, how significant is this effect? The aforementioned functional properties strongly depend on the morphology of the nanogranules10,15,19, and the electronic tunneling conduction, in particular, depends exponentially on the nanogranular diameter (d) and s24,25. In previous studies on the mechanical response of tunneling conductivity, Kaji et al. reported a significant increase in the electrical conductivity and an enhancement in the tunnel-type magnetoconductance effect under high hydrostatic pressures (up to 4 GPa) at a low temperature (4.2 K) in Co–(Al–O) nanogranular films; these phenomena were explained based on the tunneling conduction of electrons26,27. However, experimental and theoretical studies thus far have been performed only at high pressures and ultralow temperatures, and strain gauges with a metal–insulator nanogranular film structure have not been realized. To clarify the effects of tensile and compressive strains on the electrical conduction at room temperature, we selected a Co–(Mg–F) system for two reasons. One is that MgF2 is more suitable as a tunnel barrier than Al2O3 (in a Fe/insulator/Co magnetic tunnel junction, the barrier height of MgF2, 1.6 eV28, is greater than that of Al–O, 0.4–0.6 eV9), and metal–(Mg–F) nanogranular films exhibit superior tunnel-type phenomena to metal–(Al–O) nanogranular films12,16,17. The other is that Co tends to phase-separate from MgF2 since the standard formation enthalpy of CoF2 (− 665.3 kJ/mol)29 is lower than that of MgF2 (− 1112.9 kJ/mol)13,29.

In this work, we discovered a new type of strain gauge with a metal–insulator nanogranular film structure. Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films exhibit a GF approximately five times larger and an ρ0 107 times higher than those of practical metal strain gauges at room temperature. Our findings can lead to strain gauge devices characterized by high sensitivity, miniaturization, and power savings, which may enable greater integration and precise motion control.

Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films with various Co contents (26, 38, 43, and 47 at.%, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S1) were sputter-deposited using the metal Co and the insulator MgF2 targets. The strain dependence of the electrical resistance of the nanogranular films was measured by applying tensile and compressive strains using the cantilever method. To explain the results obtained, we develop a model in which the tunneling conduction of electrons is modified based on the deformation in the intergranular spacing, as presented in Fig. 1b. This deformation model also clarifies the influence of the nanostructure and ρ0 on the GF.

Results

Morphology of Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films

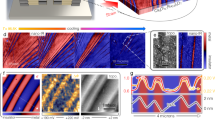

Figure 2a shows a cross-sectional high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image of the Co26Mg18F56 nanogranular film. The Co26Mg18F56 nanogranular film comprised Co nanogranules (dark area) dispersed in a MgF2 matrix (bright area), which was highly crystalline (Supplementary Fig. S2). Figure 2b shows the zero-strain nanogranular diameter (d0) and intergranular spacing (s0) of Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films estimated from the HRTEM images. With an increase in the Co content from 26 to 47 at.%, d0 increased very slightly, whereas s0 decreased.

Morphology of Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films. (a) Cross-sectional high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image of the Co26Mg18F56 nanogranular film. (b) Error bar plots of the zero-strain nanogranular diameter (d0) (red plots) and intergranular spacing (s0) (black plots) of Co26Mg18F56, Co38Mg16F46, Co43Mg13F44, and Co47Mg13F40 nanogranular films. d0 and s0 were estimated from the HRTEM image of each film.

Experimental strain dependence of the electrical resistance and GF

The GF is generally expressed as follows1,2:

where ε is the applied strain in the current flow direction, R is the electrical resistance, and R0 is electrical resistance when ε = 0.

The R0 values of the Co26Mg18F56, Co38Mg16F46, Co43Mg13F44, and Co47Mg13F40 nanogranular films were measured to be 3.46 MΩ, 70.5 kΩ, 18.9 kΩ, and 3.40 kΩ (the film dimensions are provided in Fig. 3a). R0 decreased with increasing Co content given the decrease in the intergranular spacing. In this work, we applied mechanical deformation to the Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films along the current flow direction using the cantilever method, as shown in Fig. 3a–c. Figure 3d shows the ε dependence of R of the Co26Mg18F56 nanogranular film. R increased linearly on applying a tensile strain (ε > 0) whereas it decreased linearly on applying a compressive strain (ε < 0). The same trend was observed for all other Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films (Supplementary Fig. S3a–c). The GF values of the Co26Mg18F56, Co38Mg16F46, Co43Mg13F44, and Co47Mg13F40 nanogranular films were calculated to be 10.09, 7.38, 6.44, and 6.03 (Fig. 4) using Eq. (1). The GF of the Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films increased with increasing R0. In the following sections, we discuss the ε dependence of R and then the relationship between GF and R0.

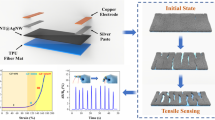

Measurement of the strain dependence of the electrical resistance of Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films. (a) Photographs of a Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular film (thickness: 330–360 nm) for the electrical resistance measurement. Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films deposited on the 100 °C glass substrate (Corning, Eagle XG) were patterned to rectangular shape (2500 μm × 500 µm). Subsequently, Ti(400 nm)/Au(250 nm) electrodes were deposited on the films (interelectrode distance: 20 µm). The patterned films were bonded to a SUS316 plate (225 mm × 18 mm × 1.5 mm) using an α-cyanoacrylate adhesive (Toagosei, Aron Alpha) along with metal foil strain gauges (Kyowa Electronic Instruments, KFGS-2-350-C1-11) to measure the applied strain on the films. (b) Front and (c) top views of the jigs to bend Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films. One end of the SUS316 plate with the film was fixed with the jig on the right, while the other end was moved up (compression) and down (tension) with the jig on the left. (d) Strain dependence of the electrical resistance of the Co26Mg18F56 nanogranular film. The mean electrical resistance for three cycles is displayed.

Structure and electrical resistivity dependence of gauge factor of Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films. The vertical axis indicates the gauge factor (GF) of Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films. The horizontal axis is the product of the structural factor ((s0 + d0)/s0) and the factor originating from tunneling conductance (ln(ρ0/C)). s0 and d0 are the intergranular spacing and nanogranular diameter without strain, respectively. ρ0 is the electrical resistivity without strain, and C is the constant.

Theoretical model for the strain dependence of electrical resistance

In nanogranular films, electrical conduction is dominated by the tunneling of electrons between neighboring nanogranules. Considering the electrical resistivity (ρ) in a nanogranular film (Abeles’s model)24,25 and the relationship between R and ρ, R = (L/A)ρ, the R of the nanogranular films can be expressed as follows:

where L is the interelectrode distance, A is the cross-sectional area of the films, C is a constant, κ is the decay rate of the electron wave functions in the matrix, Ec is the charging energy of the nanogranules, which is approximately proportional to 1/d, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the temperature. In Eq. (2), L/A originates from the film dimension and \({\text{exp}}\left( {{2}\sqrt {{\kappa E}_{{\text{c}}} {\it\text{s}}{\text{/}}{\it\text{k}}_{{\text{B}}} {\it\text{T}}} } \right)\) is derived from the tunneling conduction of electrons. The ε dependences of L and A is generally expressed as L = L0(1 + ε) and A = t0W0(1 − νε)2, where L0, t0, and W0 are the interelectrode distance, film thickness, and film width without ε, respectively; ν is the Poisson’s ratio of the Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films.

In order to discuss the ε dependence of the electronic tunneling conduction, we assume that only s is modified by applying ε and that the deformation in d is negligible because the Young’s modulus of the MgF2 thin films (115 GPa)30 is lower than that of Co (211 GPa)31, and Co nanogranules are presumed to be difficult to deform because of the size effect32,33,34. The Ec and κ values are assumed to be independent of ε. We discuss the deformation in the center distance between two adjacent nanogranules (s0 + d0), as shown in Fig. 1b, as nanogranules homogeneously disperse in nanogranular films. When ε is applied to the film, (s0 + d0) changes by (s0 + d0)ε. Because the deformation in d is negligible, the change Δs of the intergranular spacing can be expressed as Δs = (s0 + d0)ε, and the ε dependence of s can be represented as follows:

We now calculate R using Eqs. (2) and (3), and the ε dependences of L and A. For the calculation, the s0 and d0 shown in Fig. 2b and the parameters C and κEcs0/kB obtained from the T dependence of R0 (Supplementary Fig. S4a–d and Supplementary Table S1) were employed. The Poisson’s ratio of the MgF2 thin film, νMgF 2= 0.2730, was used as ν. The solid line in Fig. 3d indicates the calculated R of the Co26Mg18F56 nanogranular film. The calculated R is consistent with the measured R, which is also confirmed in all other Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films (Supplementary Fig. S3a–c). Thus, the ε dependence of R is demonstrated based on the deformation in s, that is, the tunnel barrier thickness for electronic tunneling conduction. The ε dependence of the electronic tunneling conduction, under the assumption of the deformation in both MgF2 matrix and Co nanogranules, is also discussed in Supplementary Note S1 and Supplementary Fig. S5a, b. The inverse magnetostrictive effect of the Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films is considered negligibly small in this study. This is because previous studies reported that the magnetostriction of Co–insulator nanogranular films was very small, around − 1 ppm6.

Theoretical analysis of GF

To explain the positive correlation between the GF and R0 in nanogranular films, we derived the following equation by substituting Eqs. (2) and (3), and the equations (1/L0)(∂L/∂ε) = 1 and (1/A0)(∂A/∂ε) = − 2ν1,2 into Eq. (1).

The solid line in Fig. 4 indicates the GF of the Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films calculated using Eq. (4). The same parameters (s0, d0, and C) that were used to calculate R were employed in this calculation. The calculated GF is consistent with the measured GF. Thus, we demonstrate that the GF of the nanogranular films increases with an increase in d0 and ρ0 (proportional to R0). In this study, the influence of ρ0 on the GF is greater than that of d0, as d0 of the Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films with different Co contents were very similar as shown in Fig. 2b.

Next, we consider the contribution of electronic tunneling conduction to the GF. The GF can be expressed as follows1,2:

Here, the terms 1 + 2ν and (1/ρ0)(∂ρ/∂ε) originate from the modification in the film dimension L/A and in the tunneling conduction of electrons by applying ε, respectively. In the Co26Mg18F56 nanogranular film, (1/ρ0)(∂ρ/∂ε) = 8.55 as 1 + 2ν = 1.54. Thus, approximately 85% of the GF is attributed to electronic tunneling conduction.

The Co26Mg18F56 nanogranular film exhibited a larger GF = 10.09 and a much higher ρ0 = 3.02 × 107 µΩ∙m than those of practical metal strain gauges, represented by Cu52Ni48 alloy (GF = 2.04–2.12 and ρ0 = 0.478 µΩ∙m)1,3 and Ni80Cr20 alloy (GF = 2.0–2.63 and ρ0 = 0.85–1.10 µΩ∙m)1,2. In metal strain gauges, (1/ρ0)(∂ρ/∂ε) is considered to be derived from volumetric changes in the strain gauge1,35 or by the modification in the mean free path of electrons and the effective number of free electrons36, and its value is very low (in the range of 0.30–0.39 in Cu–Ni alloys with Cu contents ranging from 50 to 60 at.%36,37). Thus, most of the GF (≃ 2) is attributed to 1 + 2ν (≃ 1.6)1,35. Therefore, the origin of the superior GF of the nanogranular films is electronic tunneling conduction, not metallic conduction.

Discussion

In summary, we demonstrate the ε dependence of R at room temperature in nanogranular films and report a large GF of 10.09 (which is approximately 5 times greater than those of metal strain gauges) and a high ρ0 of 3.02 × 107 µΩ∙m (which is 107 times higher than those of metal strain gauges) in the Co26Mg18F56 nanogranular film. The mechanical response of R is given by the modification in the electronic tunneling conduction between nanogranules originating from the deformation in s, that is, the tunnel barrier thickness. We also demonstrate that the GF of the nanogranular films increases with increasing d0 and ρ0, and that their large GF is attributed to the electronic tunneling conduction. Since the large GF is independent of magnetic properties of the Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films, a large GF can be expected in all metal–insulator nanogranular films. Our findings can help realize new strain gauge devices characterized by high sensitivity, miniaturization, and power savings, which may enable high integration of strain gauge devices and fine motion control.

Methods

Sample fabrication

Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films were sputter-deposited on 100 °C glass substrates (Corning, Eagle XG, 50 mm × 50 mm × 0.5 mm) using an RF-magnetron co-sputtering apparatus under 0.2 Pa of Ar gas, with Co and MgF2 disk targets (φ2 in.). The substrate was rotated at a constant speed of 10 rpm to obtain a homogeneous nanogranular structure. The Co content in the Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films was adjusted by changing the sputtering power of the Co target from 90 to 150 W, while fixing the power of the MgF2 target at 150 W. Film samples with different compositions are denoted by Co26Mg18F56, Co38Mg16F46, Co43Mg13F44, and Co47Mg13F40. The film thickness was regulated in the range of 330–360 nm.

Composition and structural analysis

The chemical compositions of the Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films were determined using a wavelength dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (Rigaku, ZSX Primus II). The crystal structure and morphology of the films were observed using a field-emission transmission electron microscope (JEOL, JEM-2100Plus) operated at 200 kV and a cold field-emission scanning transmission electron microscope (JEOL, JEM-ARM200F) operated at 200 kV. Observations were conducted from a cross-sectional view. Compositional and structural analyses were conducted at room temperature.

Electrical resistance measurement

For electrical resistance measurements, Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films were patterned to a rectangular shape (2500 µm × 500 µm) using a photo lithographic process (EV Group, 620 NT) and an Ar+ ion milling process (Hakuto, 10IBE-R1EM). Subsequently, patterned Ti(400 nm)/Au(250 nm) electrodes (interelectrode distance: 20 µm) were deposited on the patterned Co–(Mg–F) nanogranular films with a DC-magnetron sputtering process and a lift-off process. The glass substrate with patterned films and electrodes was cut into a width of 8 mm and was adhered to a SUS316 plate (225 mm × 18 mm × 1.5 mm) with an α-cyanoacrylate adhesive (Toagosei, Aron Alpha), as shown in Fig. 3a.

The electrical resistance of the films was measured in the in-plane direction using the two-probe method. The 2 V of the DC voltage was applied to the films. To measure the strain dependence of the electrical resistance, the films were bent using the cantilever method, as shown in Fig. 3b and c at room temperature. The strain was applied to the films in the current flow direction and was measured using a metal foil strain gauge (Kyowa Electronic Instruments, KFGS-2-350-C1-11) with GF = 2.13, attached to a glass substrate on a SUS316 plate, as shown in Fig. 3a. The temperature dependence of the electrical resistance of the films was measured by heating the film from room temperature to 70 °C on a hot plate. All measurements in this study were conducted without the application of any external magnetic field.

Calculations related to the relationship between GF, film structure, and electrical resistivity

By substituting Eq. (2) into Eq. (1), we obtain:

By expanding Eq. (6), we have:

Using (1/L0)(∂L/∂ε) = 1 and (1/A0)(∂A/∂ε) = − 2ν, we can rewrite the above equation as follows:

In the exponential term, only s is strain-dependent, we can rewrite Eq. (8) as follows:

From Eq. (3), Eq. (9) can be expressed as follows:

By substituting the electrical resistivity of nanogranular films24,25, \(\rho_{{0}} {\text{ =}}{\it\text{ C}}{\text{ exp}}\left( {{2}\sqrt {\frac{\Large{\kappa {\it\text{E}}_{{\text{c}}} {\it\text{s}}_{{0}} }}{{\Large{\it\text{k}}_{{\text{B}}} {\it\text{T}}}}} } \right)\), into Eq. (10), we can derive Eq. (4).

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Higson, G. R. Recent advances in strain gauges. J. Sci. Instrum. 41, 405–414 (1964).

Zhao, Y., Liu, Y., Li, Y. & Hao, Q. Development and application of resistance strain force sensors. Sensors (Basel) 20, 5826 (2020).

Sundqvist, B. Thermal diffusivity and thermal conductivity of Chromel, Alumel, and Constantan in the range 100–450 K. J. Appl. Phys. 72, 539–545 (1992).

Ohnuma, S., Lee, H. J., Kobayashi, N., Fujimori, H. & Masumoto, T. Co–Zr–O nano-granular thin films with improved high frequency soft magnetic properties. IEEE Trans. Magn. 37, 2251–2254 (2001).

Kijima-Aoki, H., Takeda, S., Ohnuma, S. & Masumoto, H. High-frequency soft magnetic properties of Co–SiO2 nanogranular films with large out-of-plane magnetic anisotropy. IEEE Magn. Lett. 9, 3704205 (2018).

Ohnuma, S., Ohnuma, M., Fujimori, H. & Masumoto, T. Metal–insulator type nano-granular soft magnetic thin films investigations on mechanism and applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 310, 2503–2509 (2007).

Cao, Y. et al. Novel dielectric nanogranular materials with an electrically tunable frequency response. Adv. Electron. Mater. 9, 2201218 (2023).

Rylkov, V. V. et al. Tunneling anomalous Hall effect in nanogranular CoFe-B-Al-O films near the metal-insulator transition. Phys. Rev. B 95, 144202 (2017).

Fujimori, H., Mitani, S. & Takanashi, K. Giant magnetoresistance in insulating granular films and planar tunneling junctions. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 267, 184–192 (1999).

Kijima-Aoki, H. et al. Shape effect of Co nanoparticles on the electric and magnetic properties of Co–SiO2 nanogranular films. AIP Adv. 12, 035229 (2022).

Kobayashi, N. & Masumoto, T. TMR of metal-insulator nano-granular thin films and power-saving magnetic sensor GIGS®. IEEJ Trans. Fundam. Mater. 132, 827–832 (2012).

Kobayashi, N., Ohnuma, S., Masumoto, T. & Fujimori, H. Tunnel-type magnetoresistance in metal-fluoride nano-granular films. J. Magn. Soc. Jpn. 24, 571–574 (2000).

Tregubova, T., Stognei, O., Kirpan, V. & Sitnikov, A. Magnetotransport properties of Cox(MgF2)100–x oxygen-free nanocomposites. EPJ Web Conf. 185, 01014 (2018).

Kobayashi, N., Masumoto, H., Takahashi, S. & Maekawa, S. Giant dielectric and magnetoelectric responses in insulating nanogranular films at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 5, 4417 (2014).

Kijima-Aoki, H. et al. Large magnetodielectric effect based on spin-dependent charge transfer in metal–insulator type Co-(BaF2) nanogranular films. J. Appl. Phys. 128, 133904 (2020).

Cao, Y., Umetsu, A., Kobayashi, N., Ohnuma, S. & Masumoto, H. Tunable frequency response of tunnel-type magneto-dielectric effect in Co−MgF2 granular films with different content of Co. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 122901 (2017).

Kimura, M. et al. Tunneling magnetodielectric effect in Co–Al2O3 granular films. Mater. Trans. 63, 1677–1681 (2022).

Kravets, A. F., Borodinova, T. I. & Kravets, V. G. Strong plasmon enhancement of magneto-optical Kerr rotation in Co–AlO nanogranular films coated with gold nanoparticles. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 33, 302–307 (2016).

Simdyanova, M. A. et al. Effect of granule sizes on magneto-optical spectra of nanocomposites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 595, 171550 (2024).

Kobayashi, N. et al. Giant Faraday rotation in metal-fluoride nanogranular films. Sci. Rep. 8, 4978 (2018).

Ito, K. et al. Enhanced orbital magnetic moment in an FeCo-BaF2 granular film revealed by x-ray magnetic circular dichroism. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 606, 172361 (2024).

Kobayashi, N., Masumoto, H., Takahashi, S. & Maekawa, S. Optically transparent ferromagnetic nanogranular films with tunable transmittance. Sci. Rep. 6, 34227 (2016).

Cao, Y., Kobayashi, N., Kijima-Aoki, H., Zhang, J. & Masumoto, H. Multifunctional spin-dependent tunneling: from tunnel magnetodielectric to magneto-optic and Faraday effects. Acc. Mater. Res. 6, 979–990 (2025).

Sheng, P., Abeles, B. & Arie, Y. Hopping conductivity in granular metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 31, 44–47 (1973).

Helman, J. S. & Abeles, B. Tunneling of spin-polarized electrons and magnetoresistance in granular Ni films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 37, 1429–1432 (1976).

Kaji, S. et al. Pressure enhanced tunnel magnetoresistance in Co-Al-O granular films. Phys. Rev. B 68, 054429 (2003).

Kaji, S. et al. Electrical transport and magnetoresistance in Co–Al–O granular films under high pressure. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 74, 2783–2790 (2005).

Moriyama, T., Mitani, S. & Takanashi, K. Tunnel magnetoresistance in Fe/MgO/MgF2/Co junctions. J. Magn. Soc. Jpn. 26, 405–409 (2002).

Smithells, C. J. Metals Reference Book 4th Edition. Vol. Ⅰ, 244–245 (Butterworth & Co. (Publishers) Ltd, London, 1967).

Granata, M. et al. Optical and mechanical properties of ion-beam-sputtered MgF2 thin films for gravitational-wave interferometers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 17, 034058 (2022).

Doi, H., Fujiwara, Y., Miyake, K. & Oosawa, Y. A systematic investigation of elastic moduli of WC-Co alloys. Metall. Trans. 1, 1417–1425 (1970).

Li, H., Han, Y., Duan, T. & Leifer, K. Size-dependent elasticity of gold nanoparticle measured by atomic force microscope based nanoindentation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 053104 (2019).

Gu, Q. F., Krauss, G., Steurer, W., Gramm, F. & Cervellino, A. Unexpected high stiffness of Ag and Au nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 045502 (2008).

Liang, L., Ma, H. & Wei, Y. Size-dependent elastic modulus and vibration frequency of nanocrystals. J. Nanomater. 2011, 1–6 (2011).

Meier, J. H. On the transverse-strain sensitivity of foil gages. Exp. Mech. 1, 39–40 (1961).

Kuczynski, G. C. Effect of elastic strain on the electrical resistance of metals. Phys. Rev. 94, 61–64 (1954).

Hu, C., Gao, Y. & Sheng, Z. The piezoresistance coefficients of copper and copper-nickel alloys. J. Mater. Sci. 35, 381–386 (2000).

Acknowledgements

A part of this work was supported by “Advanced Research Infrastructure for Materials and Nanotechnology in Japan (ARIM)” of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). Proposal No. JPMXP1224TU0157.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aids for Scientific Research (Grant Nos. 23K26371 and 24H00388) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). T.U. was supported by Grant-in-Aids for Scientific Research (Grant No. 24KJ0362) from the JSPS. S.M. was supported by Grant-in-Aids for Scientific Research (Grant No. 24K00576) from the JSPS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.U. and Y.H. prepared the samples. T.U. performed the experiments. T.U., C.W., N.K., and H.M. discussed the data. C.W., S.T., and S.M. developed the theoretical model. All the authors contributed to the writing and editing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Uchiyama, T., Wang, C., Hasegawa, Y. et al. High-sensitive mechanical response in metal–insulator nanogranular films with large gauge factor. Sci Rep 15, 37337 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24084-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24084-7