Abstract

Minas Gerais is, in economic and population terms, the third-largest state in Brazil, where significant investments have been made in producing photovoltaic energy, primarily in distributed micro and mini-generation. Despite the growing demand, no computational model in the literature efficiently predicts future values of solar irradiation, the source of photovoltaic energy, for the entire state. The vast majority of works use empirical models for specific regions of the state. A few papers that use computational models, even those dealing with broader regions of the state, create local models for each point of data observation. This work presents the methodology and development of an optimized computational model for predicting solar irradiation applied throughout Minas Gerais. The presented methodology can be applied to various machine-learning models and used in different locations. Here, we utilize data from 67 meteorological stations distributed throughout all state regions, spanning 20 years of measurements. Different approaches are studied, manipulating the data used in the training and test databases, so that we can answer two main questions: Does the addition of geolocation data improve the prediction of solar irradiation? Is it possible to efficiently predict solar irradiation values in a place without meteorological stations? Experiments have shown that using data from neighboring cities is either detrimental or irrelevant to the results. However, using data from neighboring cities for transfer learning yields good results, generally comparable to those obtained in models that utilize the city’s database.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research background and literature overview

Predicting solar irradiation values is useful for different areas of knowledge, especially agriculture1,2,3,4 and energy production5,6. The efficiency of this prediction is essential in both in systems planning and in the execution of short, medium, and long-term actions in these knowledge areas7. Considering that the physical measurement of solar irradiation, due to the cost and technology involved, is not possible for all locations worldwide, predicting future values is usually restricted to areas with measurement stations8.

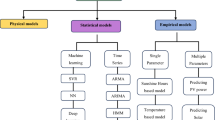

When predicting solar irradiation values is necessary or desired, and there are no meteorological stations, prediction models are used9,10. Empirical models have long been used for this purpose. However, these generally present strong generalizations and do not consistently provide the best results11. In recent years, with the advancement of machine learning techniques, computational resources have been leveraged to partially or entirely replace empirical models, yielding promising results12,13. Regardless of the classification method, it must be appropriately calibrated for efficient execution.

There are many challenges in solar irradiation prediction; therefore, different techniques are employed in various locations14,15. Furthermore, the literature clearly shows that a prediction model that works well in one place is not necessarily the best in another, just as the best variables for one place are not necessarily the best for another16. When selecting the most suitable machine learning model, it is essential to consider whether the data originates from weather stations or satellites17,18 and the desired prediction granularity19,20,21,22. Regardless of the type of data and model, hybrid methods that optimize the hyperparameters of the learning models have better results23,24,25.

In this paper we present a framework for optimizing solar irradiation prediction computational models applied to data from Minas Gerais state, Brazil. Minas Gerais is in economic and population terms the third largest state in Brazil, with a territory of 586,852.35 \(km^2\), and a population of 20 million inhabitants. Its Gross Domestic Product is the third largest in Brazil26 and with a monthly energy demand of approximately \(5\times 10^6\) MWh27, the state is in a constant process of expanding its energy matrix. In Brazil, the power grid’s primary source of production is hydroelectric resources. However, the exploitation of these resources is nearing its limit, and the strong dependence on a seasonal energy source causes disturbances and price fluctuations during periods of drought. In this way, considerable investment has been made in producing photovoltaic energy, primarily in distributed micro- and mini-generation28.

Despite this growing demand, few published studies use computational models to predict future solar irradiation values in Minas Gerais. We found 14 works that address this topic in this region, and only two of these cover the entire state, using a daily granularity. One of these uses empirical models, and the other uses computational models. Most papers use empirical models for specific regions of the state29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Some use computational resources to solve more detailed numerical models or apply empirical models as input to computational models38,39. The most comprehensive works are40,41.

Reference40 compiled a database with 51 stations, showing the challenges in collecting and cleaning data. Fifteen different empirical models are applied to all available cities. The best result, as determined by the \(R^2\) metric, was 59.58%, with an average of 36.97%. Reference41 uses the same database as the previous work, differentiated by applying computational models, specifically Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and Multivariate Adaptive Regression Spline (MARS). The present proposal uses them as the main parameter for comparing results.

Two other works that do not directly deal with solar irradiation prediction, however, are strongly related to the present paper are42, where authors use a computational approach on this same database, observing the entire state of Minas Gerais using an artificial neural network, random forest, support vector machine, and multiple linear regression for the prediction of reference evapotranspiration, and43 that maps data on solar radiation and rainfall in Minas Gerais from different bases, showing how geographic factors influence these measurements. The paper presents an interesting set of maps showing, in addition to the climatic factors, the study’s objective, the location and type of various meteorological stations, and their maintainers. However, the work is just mapping, and no prediction is made.

This research distinguishes from the previous ones by proposing a geolocated transfer learning framework that leverages spatial dependencies by incorporating data from neighboring meteorological stations. This fundamentally departs from previous works by enabling robust predictions in areas without direct meteorological stations, a challenge largely unaddressed by the current literature’s focus on isolated or empirical models. This innovative approach, specifically the use of neighboring city data for transfer learning, represents a key methodological advancement in solar irradiation forecasting for regions with sparse meteorological networks.

Research significance and motivation

Brazil has an estimated potential of 176 GW for producing electricity from hydro resources. However, approximately 108 GW of this is already in use, and more than half of the available potential is located in the Tocantins-Araguaia and Amazon watersheds. Consequently, the expansion of hydroelectric resource utilization has encountered recent obstacles, including adverse socio-environmental consequences stemming from the execution of large hydroelectric ventures, substantial upfront investment expenditures, and the complexity of establishing power plants close to significant consumption hubs, this, in turn, necessitates supplementary investments in extensive transmission infrastructure to transport the generated electricity44.

Given the importance of the state of Minas Gerais in the Brazilian economy, its potential for photovoltaic energy generation, the growing demand for new energy sources, especially renewable ones, and the expectation of increased installation of photovoltaic power plants in the state, it is clear that there is a need for different studies to develop efficient forecasting models for solar radiation resources in this location. The scarcity of research in the literature on this region of the country, particularly utilizing computational resources, underscores the need for further investigation.

Research objectives

In this work, we present a computational model for the entire state of Minas Gerais and the methodology for its development. This model utilizes data from 67 weather stations distributed across all state regions, as well as data from an additional 67 stations in neighboring states, with measurements taken over more than 20 years in 129 cities. Different approaches are studied, manipulating the data used in the training and test databases, to answer the following question: Does the addition of geolocation data improve the prediction of solar irradiation? Is it possible to efficiently predict solar irradiation values in a place without meteorological stations?

Two different approaches are compared in this work. In the first experiment, we add data from neighboring stations to the training data of each station, aiming to verify how the inclusion of geolocation data affects the results. In a second moment, we remove from the training base the data for the location where we want to make the forecast, leaving only the data from the neighboring stations. In this way, we have a training base without data from the location where the forecast will be performed. Both methods are compared with the punctual executions of each station.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2.1 provides a detailed description of the database. Section 2.2 presents all the performance metrics adopted to compare this proposal with other works, describes the framework for selecting the fittest machine learning model and optimizing its hyperparameters, and also presents the methodology for developing a geolocated model. Section 3 details the proposed framework execution over the utilized database. Finally, conclusions and extensions are considered in Section 5.

Material and methods

Data

The National Institute of Meteorology (Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia-INMET)45 maintains and makes available data from more than 500 meteorological stations throughout Brazil, 68 of which are automatic meteorological stations in Minas Gerais-MG. This work utilized data from various periods, spanning from December 2002 to December 2021, collected from 67 different stations in 66 cities across all regions of Minas Gerais, which formed its primary database. The availability of data at each station depends on several external factors, including the installation date, potential failures, and scheduled maintenance periods. We also used data from stations in other states besides Minas Gerais to develop the methodology proposed in this work. To select these stations, we calculated the 10 closest stations for each of the 66 cities in Minas Gerais. All cities on this list were included in the database for this work, regardless of whether they are located in Minas Gerais or not. Data from 67 stations outside Minas Gerais were used: 17 from the state of São Paulo (SP), 13 from Rio de Janeiro (RJ), 12 from Espírito Santo (ES), 11 from Bahia (BA), 9 from Goiás (GO), 4 from the Distrito Federal (DF), and 1 from Mato Grosso do Sul (MS). Supplementary Table S1 details the code of each station, its city, federative unit, geographic coordinates, observed period, and the total data analyzed, while Fig. 1 highlights all cities on the map where there are analyzed weather stations, with colors differing between states. In this work, 20 variables were used. Table 1 describes them according to45.

It is worth noting that the INMET data have an hourly measurement granularity. In this work, we used the daily values for each variable, considering that for the variables Global and Qo, the sum of each day was used, and for the others, the average of the daily readings. The Qo variable, unlike the others, is not measured by devices and is not available through INMET. This variable was synthetically generated by the PySolar48 library. The choice of daily granularity is mainly to facilitate comparison with the main works in the literature. Different granularities, such as hourly and monthly, yield distinct results and are typically employed in distinct problems.

Methodology

Performance metrics

The metrics described in Table 2, as outlined in the scikit-learn library documentation49, were used to evaluate the performance of the methods. This Table also describes the purpose of using each metric, the best and worst results that can be found, and what they mean.

Performance profiles

Performance profiles are a valuable resource in optimization benchmarking. They provide a comprehensive method for assessing and comparing the efficacy of diverse optimization algorithms across a range of test scenarios. When we view each station as an independent problem, we deal with 67 individual problems. These problems are analyzed under five distinct scenarios, each evaluated across six different metrics. Consequently, this approach yields a comprehensive dataset of 2010 distinct results. Managing such a vast volume of results can be challenging, particularly when dealing with potentially inconsistent metrics. To address this, we employ the technique of evaluating models through performance profiles, as detailed by50. This approach facilitates a graphical assessment of one solver’s superiority over another, and its methodology is elaborated upon below.

Consider a set P of test problems \(p_{j}\), with j = 1, 2, ..., \(n_{p}\), a set A of algorithms \(a_{i}\), with i = 1, 2, ..., \(n_{a}\) and \(t_{p,a} > 0\) a performance metric (such as compute time, average, etc.). The performance ratio is defined as:

The algorithm performance profile is defined as:

where \(\rho _{a}(\tau )\) is the fraction of problems solved by the algorithm with performance within a factor \(\tau\) of the best performance obtained, considering all algorithms.

Transfer learning

Transfer learning is a machine learning technique that involves utilizing knowledge gained from one task or domain to enhance the performance of a different, yet related, task or domain. In transfer learning, a pre-trained model, typically trained on a large dataset, serves as a starting point for a new task, rather than training a model from scratch.

The idea behind transfer learning is that the knowledge acquired by a model while learning one task can be leveraged to accelerate learning or improve generalization on a different task. By starting with a pre-trained model, the model already possesses learned features, patterns, or representations that are generally useful across tasks. These learned features can be utilized as a foundation for the new task, allowing the model to adapt and specialize more quickly.

The process of transfer learning typically involves the following steps:

Pre-training: A model is trained on a large dataset from a source task or domain. This training step is usually computationally expensive and time-consuming.

Feature extraction: The pre-trained model is used to extract relevant features or representations from the data of the source task. These features capture important patterns or information in the data.

Fine-tuning: The extracted features are then used to initialize a new model that is specifically designed for the target task or domain. This new model is trained on a smaller dataset specific to the target task, which is often labeled or annotated.

Adaptation: The new model is further trained on the target task dataset, typically with a lower learning rate, to adjust the model’s parameters to the task’s specific requirements. This step allows the model to fine-tune its learned features and improve its performance on the target task.

Transfer learning can be particularly beneficial when the target task has limited data available, as it helps mitigate the risk of overfitting and improves the model’s ability to generalize. It has been successfully applied in various domains, including computer vision, natural language processing, and audio analysis, enabling the development of more accurate and efficient models.

Automatic feature selection

The feature selection process is crucial in building machine learning models. This process implies selecting the most relevant variables or features from a dataset. It is essential for reducing dimensionality, enhancing model interpretability, and improving overall performance.

The developer can perform the variable selection process arbitrarily, where the variables judged attractive are used and others discarded. In this process, the correlation matrix of the variables is usually observed. Considering the numerous databases and their combinations, this approach would be highly time-consuming and inefficient for the present work. In this way, the feature selection process was performed automatically by an optimization algorithm, which also optimized the hyperparameters of the machine learning model. Therefore, all available variables were initially considered usable in training the final model. However, the optimization process selected only those that performed best. Details of this process are described below in the 2.2 section.

Hybrid computational approach

Aiming at an efficient comparison parameter for the geolocated model, we developed a punctual computational model for each station in Minas Gerais. When dealing with a specific station individually, we refer to it as the Target Station. The methodology applied for the development of these models has already been widely validated in41,51,52 and is described below: Initially, all machine learning models are individually executed to find the best set of hyperparameters for each model applied to each station. Each machine learning model has a set of values containing the upper and lower bounds of its hyperparameters. At this initial moment, it is possible to choose to use a specific subset of variables, all available variables or to apply a feature selection technique. After initial settings, the optimization algorithm randomly generates a population of candidate solutions. Each candidate solution represents a set of hyperparameters associated with the machine learning model. If the feature selection process is carried out automatically, each solution will have its own set of variables. The solution is evaluated using a k-fold cross-validation strategy, where the objective to be minimized is the root mean square error (RMSE) value, calculated between the observed and predicted values. As we work with time series, it is worth noting that in the folds of the cross-validation process, future values are not used for training. This process is known as Time Series Split Cross-Validation. When the stopping criterion is met, the evolutionary cycle ends, and the solution that presents the best RMSE is stored. With the models already executed, we can analyze which one performed the best at the Target Station and determine the optimal configuration for its hyperparameters. Figure 2 illustrates this process.

Geospatial model

This paper introduces a novel geolocated transfer learning (TL) approach designed to overcome the limitations of localized prediction models. Unlike conventional methods that typically use data solely from the target station or rely on satellite imagery (which, while intrinsically geolocated, can be less accurate than ground measurements when available), our framework explicitly integrates detailed geolocation data from multiple meteorological stations. Specifically, for developing a geospatial computational model in Minas Gerais, data from the N closest stations to the Target Station are aggregated into a unified dataset enriched with comprehensive geolocation information. The distinct innovation lies in our two-pronged strategy: (1) enhancing the Target Station model by incorporating neighboring data into its training, thereby creating a truly ’geolocated’ model, and (2) critically demonstrating the feasibility of solar irradiation prediction in areas without existing meteorological stations. This is achieved by constructing a training base exclusively from neighboring station data and validating it against the Target Station’s data, a process we define as transfer learning. This approach enables the model to learn broader spatial patterns and generalize effectively, addressing a significant gap in the current literature, where predictions are often constrained to measured locations.

For developing a geospatial computational model of Minas Gerais, the data from the N closest stations to the Target Station are grouped in a single base with the geolocation data of all the stations involved. The methodology described in Section 2.2 is then applied to this new database. However, the validation process only takes place with the Target Station data. In this way, the model representing the Target Station will also incorporate data from neighboring stations into its formulation and can be considered a geolocated model. Figure 3 shows this dynamic, while Fig. 4 illustrates this step on the map. There is a need for special care when dividing the training and testing intervals. Some stations, such as Caratinga and Espinosa, do not have data up to the end of the usually observed period, December 31, 2021. Therefore, data from stations neighboring these bases must also be dropped on the date of the last reading of these stations when they are the Target Station.

In order to verify the feasibility of predicting solar irradiation in areas without meteorological stations, we employed an alternative approach, slightly modifying the methodology described above. We created a database with data from the N closest stations to the Target Station. However, we removed the Target Station data from the training base. In this manner, all training is conducted using data from neighboring stations, and validation is performed using data from the Target Station. This process is, in essence, what we refer to as transfer learning. Figure 5 shows the geospatial base creation process without the presence of the Target Station in the training base.

Computational experiments, analysis and discussion

Although the methodology described above can be applied to any forecast horizon, in this work, the forecast is made one day ahead, using data from the previous day. As the data from each station has different periods of availability in each Scenario and Target Station combination, different periods were used for the machine learning model’s testing and training periods.

First phase of experiments

In the developemnt of process of the present study, different approaches were tested. Initially, the framework developed did not account for the transfer learning process. At this stage, experiments were conducted using various machine learning models. We will report the results found at this stage in the following to justify some choices made in the final process.

At this preliminary stage, we also analyzed the biome’s correlation with the results. Initially, we assumed this variable would be strongly correlated, given that the biome is highly influenced by various climatic factors, such as altitude and the region’s general geography. However, in most of the tests performed, the variable selection process excluded this exogenous variable, demonstrating that it did not influence the results. Therefore, we chose not to use this data in the second phase of the experiments.

Initially, six different machine learning models were applied, following the methodology described in41. The models were Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Extreme Learning Machine53,54 (ELM), Elastic Net55 (EN), Multivariate Adaptive Regression Spline56,57 (MARS), Extreme Gradient Boosting58,59 (XGB), and Support Vector Regression60 (SVR). Of all the applied models, the one that demonstrated the best performance was the ELM, as shown in Table 3, which displays the normalized area under the curves of the performance profiles for each learning model.

Second phase of experiments

Considering that the ELM model yielded the best result in the initial tests, we applied it exclusively in the second development stage. ELM is a type of machine learning algorithm, specifically a variation of the feedforward neural network, and its training is done differently from most other neural networks. It is one of the most used machine-learning models for predicting solar irradiation61.

Unlike traditional neural networks, which use a stepwise, iterative training process to adjust the weights of connections between layers, ELM randomly assigns these weights. ELM does not require a long and time-consuming training phase, making it much faster than other machine learning methods.

ELM is also known to be highly efficient in terms of processing and requires relatively little training data to produce accurate results. It is often used in classification and prediction tasks such as pattern recognition, time series analysis, and signal processing.

As an optimizer, we use a Simple Genetic Algorithm (SGA). SGA is a method to solve optimization problems with and without constraints, inspired by natural selection. Each possible solution to the problem is considered an individual from the population, and the algorithm repeatedly modifies a population in search of fitter individuals. At each step, the algorithm selects individuals from the current population as parents and uses them to produce offspring for the next generation. Over successive generations, the population evolves towards an optimal solution. The implementation used was the Pygmo library62.

All scenarios presented were executed 30 times independently, aiming at greater statistical confidence in the results found. Five different scenarios were analyzed for all stations:

-

1.

The Target Station database was used alone for training and testing. This scenario represents the station model independently, is the one traditionally analyzed in other works40,41, and serves as the main object of comparison of the results.

-

2.

Data from the two closest neighboring cities were added to the Target Station training bases. Only Target Station data was used as a test basis. In this scenario, we verify the benefit of using data from neighboring stations to compose the training base. We can consider the models generated in this scenario as geolocated.

-

3.

Data from the two closest neighboring cities were used as a training base, and data from the Target Station as a test base. This scenario tries to verify the feasibility of applying transfer learning using cities with meteorological stations as training to generate models for cities without meteorological stations.

-

4.

Data from the four nearest neighboring cities were added to the Target Station training bases. Only Target Station data was used as a test basis. This scenario is similar to scenario 2, with the only difference being the number of stations used.

-

5.

Data from the four nearest neighboring cities were used as a training base, and Target Station data as a test base. This scenario is similar to scenario 3, with the only difference being the number of stations used.

Supplementary Table S2 presents the averages of 30 independent runs of all city scenarios. The best values found for each city are highlighted in bold, and the standard deviation is in parentheses. Furthermore, Supplementary Table S3 presents the count of the selected variables across 30 independent runs for all scenarios in all cities. Table 4 presents the parameters used in the genetic algorithm, while Table 5 presents the ELM parameters, as well as the search intervals employed.

Discussion

Considering scenario 1 and comparing it with the main works found in the literature40,41, this work focuses on 16 stations that were not studied in the literature. At 22 stations, the results presented here are more favorable. In the other 29 stations, the results reported in the literature are better, always observing the metric \(R^2\). These results suggest that the MARS model may be superior to the ELM. However, the experiments presented here are insufficient to confirm this situation. This variation in the results can be attributed to several factors, including the observed interval, the percentage of division between the training and test sets, and the differences between the empirical and machine learning models used in other works. Regardless, this work aims to demonstrate the viability of using geographically distant data to forecast values without meteorological stations, rather than to obtain better models where stations already exist. The comparison of this scenario’s results with those found in the literature is presented in Supplementary Table S4, with the best results from each city highlighted in bold.

Through scenarios 2 and 4, we attempted to verify the hypothesis that adding data from neighboring stations would improve the results at a specific point. We found that for most stations, 47 exactly, adding these data to the training base was not advantageous. That is, in 47 stations, the result of scenario 1 was better than the results of scenarios 2 and 4. In 11 stations, scenario 2 had better results, and in 9, scenario 4 had better results, always observing the metric \(R^2\). This outcome suggests that a simple distance-based selection of neighboring stations may not be sufficient to capture the intricate spatial dependencies in a region with diverse topography, such as Minas Gerais. While proximity is a factor, variations in altitude, terrain, and microclimates can significantly influence solar irradiation patterns, leading to a non-uniform decay of spatial correlation. Therefore, a station’s geographical closeness does not automatically guarantee a strong positive correlation in solar irradiation. In some cases, it may even introduce noise if the neighboring station is in a significantly different microenvironment.

Scenarios 3 and 5 present the central hypothesis of this work, where we apply transfer learning to predict solar irradiation values in cities without meteorological stations. To this end, as previously explained, we consider each city as if it did not have a meteorological station present, and we use data from neighboring cities to train the model. We only use data from the Target Station to confirm the transfer learning efficiency in the model validation period.

In scenario 3 specifically, in 39 of the 67 cities, there were independent executions where the metric \(R^2\) was negative. In 16, the average results of this metric were less than zero. In the other 23, even with some bad executions, the final average was reasonable. In the 2010 independent runs (\(67 \times 30\)), 234 had a metric \(R^2\) value less than zero, which is approximately 11.65%. Figure 6 shows the Boxplot of \(\hbox {R}^2\) for each city, considering only the executions where \(\hbox {R}^2\) was positive. Considering only these executions, \(\hbox {R}^2\) mean was 0.5633 with a standard deviation of 0.1849.

In scenario 5, in 11 cities, there were independent executions where the metric \(R^2\) was negative, and in 4, the average results of this metric were less than zero. Analyzing the total executions in this scenario, of the 2010 independent executions (\(67 \times 30\)), 83 had a metric \(R^2\) less than zero, which is approximately 4.13%. Figure 7 shows the Boxplot of \(\hbox {R}^2\) for each city, considering only the executions where \(\hbox {R}^2\) was positive. Considering only these executions, \(\hbox {R}^2\) mean was 0.5851 with a standard deviation of 0.1681.

The negative values of the \(\hbox {R}^2\) metric are associated with two main groups of factors: (1) geographic and topographic characteristics that generate local microclimates distinct from those of neighboring cities used in training; and (2) the scarcity or inadequacy of data, which compromises the spatiotemporal representativeness of the model. The average temperature decreases approximately 6.5 \(^{\circ }\)C for each kilometer of altitude due to the environmental lapse rate. In cities located at high altitudes or on steep slopes, the microclimate differs substantially from that of neighboring stations at lower altitudes. Automatic modeling based on neighborhood data, without accounting for altitudinal differences, can lead to significant underestimations or overestimations.

Figure 8 shows the scatter plots of the measured and estimated solar irradiation for the best individual executions of each station, considering the \(R^2\) metric, grouped by scenarios. In it, we highlight the ideal regression line, where the predicted values match the measured ones within a 20% margin. Figure 9 shows the plot of the performance profiles for the five scenarios, considering all five metrics used. Table 6 shows the values of the curves of the normalized performance profiles. Analyzing these results, despite the performance profile curves of the five scenarios being very close and the scatter plots being very similar, we can confirm that, for this study, using neighboring cities’ data in the training base setup was not advantageous, as the curve of scenario 1 grew faster than those of scenarios 2 and 4. Regarding the use of transfer learning for data forecasting in areas without meteorological stations, the analysis through performance profiles suggests that, for this study, increasing the number of cities used generates better performance. However, analysis of variance (ANOVA) produced a p-value of 0.206. This value indicates that there is no statistically significant difference between the sample means of the groups. This result, when analyzed in conjunction with the proximity of the curves from scenarios 3 and 5 to the curve from scenario 1, suggests that transfer learning can be used efficiently, considering that the scenarios where learning transfer occurred had statistically similar results to those of the original scenario. It also reinforces the inefficiency of using neighboring stations to improve the prediction of the target station (scenarios 2 and 4).

Model strengths and limitations

With these results, it is clear that, in most cases, the use of transfer learning is a viable option for predicting solar irradiation in areas without meteorological stations, even if the results are not satisfactory in some stations. Observing the improvement between the results of scenario 5 and scenario 3, we can also see that the number of cities used in the training base is relevant. In this study, the results improved with the increase in the number of stations in the training base, as evident in 46 stations.

Conclusion

This work presents the methodology and results of applying geolocation data in constructing computational models to predict solar irradiation in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Data from 134 cities, acquired over more than 20 years of observations, were analyzed to answer two main questions: Does adding geolocation data to predict solar irradiation improve results? Is it possible to efficiently predict solar irradiation values in a place without meteorological stations?

Five different scenarios were performed, where we verified the independent results in each of the 67 cities in Minas Gerais where there are meteorological stations, we analyzed the inclusion of geolocation data from neighboring cities to improve the results, and we applied transfer learning in a methodology to allow prediction in cities where there are no weather stations.

The results of scenario 1, with independent executions of each station, were compared to other works found in the literature and served as a comparison parameter for the other studies conducted. In scenarios 2 and 4, we added geolocation data from neighboring cities, and we found that this type of approach generally worsens the results compared to scenario 1. In scenarios 3 and 5, we used data from the neighboring stations of the studied cities to compose the training bases. We used data from each analyzed city as a test base, thus applying the transfer learning technique. The study of these scenarios revealed that, in most cases, it is possible to efficiently predict solar irradiation values where no meteorological stations are available in the databases of neighboring cities. The study of these scenarios also reveals that the choice of the number of cities used in the training database creation process affects the results obtained.

The main achievement of this work is the development of models for predicting solar irradiation in cities lacking meteorological stations. The vast number of cities analyzed allowed us to verify that transfer learning techniques work for most sites. One limitation of this work is the choice of cities that should be used to compose the training base, as the current selection relies solely on Euclidean distance. Initially, we verified that using the 5 stations closest to the location we want to predict yields the best results. However, more studies can be done in this area. This paper’s contributions are summarized as follows:

-

1.

A methodology for transfer learning to geographically distributed locations;

-

2.

Methodology for developing an optimized computational model;

-

3.

Automatic feature selection;

-

4.

Unprecedented application of the ELM model for predicting solar irradiation in Minas Gerais;

-

5.

Study covering the entire state of Minas Gerais;

This work represents a significant step forward in predicting solar irradiation in regions lacking meteorological stations, particularly in Minas Gerais, Brazil. The proposed methodology, which combines geolocation data and transfer learning techniques, has demonstrated effectiveness in achieving high accuracy in solar irradiation predictions.

The intelligent selection of neighborhood stations can drive potential improvement for the model to compose the training database. The choice of stations can significantly impact the model’s performance, and future research should focus on refining the criteria for selecting the optimal set of stations, thereby enhancing the accuracy and applicability of the developed models.

Despite the limitations, this study contributes valuable methodologies and insights to propose precise solar irradiation predictions and further advancements in renewable energy planning and implementation. The findings of this study could be used to develop more efficient and cost-effective solar energy systems, which could help reduce our reliance on fossil fuels and combat climate change.

Data availability

Code, data and materials can be obtained upon request from samuel@cefetmg.br.

References

Ferreira, L. B., da Cunha, F. F., de Oliveira, R. A. & Fernandes Filho, E. I. Estimation of reference evapotranspiration in brazil with limited meteorological data using ANN and SVM—A new approach. J. Hydrol. 572, 556–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.03.028 (2019).

Ferreira, L. B., da Cunha, F. F. & Fernandes Filho, E. I. Exploring machine learning and multi-task learning to estimate meteorological data and reference evapotranspiration across brazil. Agric. Water Manag. 259, 107281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2021.107281 (2022).

Castro, J. R. D. et al. Parametrization of models and use of estimated global solar radiation data in the irrigated rice yield simulation. Revista Brasileira de Meteorologia 33, 238–246 (2018).

Santos, M. V. C. et al. A modelling assessment of the maize crop growth, yield and soil water dynamics in the Northeast of Brazil. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 897–904 (2020).

Rodríguez, F., Martín, F., Fontán, L. & Galarza, A. Ensemble of machine learning and spatiotemporal parameters to forecast very short-term solar irradiation to compute photovoltaic generators’ output power. Energy 229, 120647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.120647 (2021).

De Oliveira, I. F. B., Vasconcelos, L. A. & Freitas, I. S. O. Impact of dirt on the performance of photovoltaic plants in the north of minas gerais. In 2023 15th IEEE International Conference on Industry Applications (INDUSCON), 858–863. https://doi.org/10.1109/INDUSCON58041.2023.10374784 (2023).

Chueca, E. et al. Early adopters of residential solar pv distributed generation: Evidence from Brazil, Chile and Mexico. Energy Sustain. Develop. 76, 101284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2023.101284 (2023).

Jiang, C. & Zhu, Q. Evaluating the most significant input parameters for forecasting global solar radiation of different sequences based on informer. Appl. Energy 348, 121544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.121544 (2023).

Babatunde, O., Munda, J., Hamam, Y. & Monyei, C. A critical overview of the (im)practicability of solar radiation forecasting models. e-Prime Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 5, 100213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prime.2023.100213 (2023).

Figueiró, L. S. d. P., Bonfá, C. S. & Santos, L. d. C. Calibration and evaluation of the Hargreaves-Samani equation for estimating reference evapotranspiration: A case study in Northern Minas Gerais, Brazil. Rev. Gest. Secr. 16, e4638 (2025).

Krishnan, N., Kumar, K. R. & Inda, C. S. How solar radiation forecasting impacts the utilization of solar energy: A critical review. J. Clean. Product. 388, 135860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.135860 (2023).

Nawab, F. et al. Solar irradiation prediction using empirical and artificial intelligence methods: A comparative review. Heliyon 9, e17038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17038 (2023).

Gupta, R., Yadav, A. K., Jha, S. & Pathak, P. K. Comparative analysis of advanced machine learning classifiers based on feature engineering framework for weather prediction. Scientia Iranica –, https://doi.org/10.24200/sci.2024.61305.7242 (2024). https://scientiairanica.sharif.edu/article_23690_0bfb4185871b929ab5a7f26e966abcfb.pdf.

de Freitas Viscondi, G. & Alves-Souza, S. N. A systematic literature review on big data for solar photovoltaic electricity generation forecasting. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 31, 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2018.11.008 (2019).

Demir, V. & Citakoglu, H. Forecasting of solar radiation using different machine learning approaches. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 887–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-022-07841-x (2023).

Gürel, A. E., Ağbulut, Ü., Bakır, H., Ergün, A. & Yıldız, G. A state of art review on estimation of solar radiation with various models. Heliyon 9, e13167 (2023).

Gupta, R., Yadav, A. K. & Jha, S. Harnessing the power of hybrid deep learning algorithm for the estimation of global horizontal irradiance. Sci. Total Environ. 943, 173958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173958 (2024).

Ganvir, C., Dinesh, D., Gupta, R., Jha, S. & Raghuvanshi, P. K. Prediction of global horizontal irradiance based on explainable artificial intelligence. In 2024 International Conference on Intelligent and Innovative Technologies in Computing, Electrical and Electronics (IITCEE), 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1109/IITCEE59897.2024.10467440 (2024).

Zhang, J., Zhao, L., Deng, S., Xu, W. & Zhang, Y. A critical review of the models used to estimate solar radiation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 70, 314–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.124 (2017).

Das, U. K. et al. Forecasting of photovoltaic power generation and model optimization: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 81, 912–928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.08.017 (2018).

Guermoui, M., Melgani, F., Gairaa, K. & Mekhalfi, M. L. A comprehensive review of hybrid models for solar radiation forecasting. J. Clean. Product. 258, 120357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120357 (2020).

Zhou, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, D., Liu, X. & Wang, Y. A review on global solar radiation prediction with machine learning models in a comprehensive perspective. Energy Conversion Manag. 235, 113960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2021.113960 (2021).

Yadav, A. K. & Chandel, S. Solar radiation prediction using artificial neural network techniques: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 33, 772–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.08.055 (2014).

Akhter, M. N., Mekhilef, S., Mokhlis, H. & Mohamed Shah, N. Review on forecasting of photovoltaic power generation based on machine learning and metaheuristic techniques. IET Renew. Power Generation 13, 1009–1023. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-rpg.2018.5649 (2019) https://ietresearch.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1049/iet-rpg.2018.5649.

Jha, A. et al. An efficient and interpretable stacked model for wind speed estimation based on ensemble learning algorithms. Energy Technol. 12, 2301188. https://doi.org/10.1002/ente.202301188 (2024) https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/ente.202301188.

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Produto Interno Bruto - PIB (2020).

Ministério de Minas e Energia. Consumo Mensal de Energia Elétrica por Classe. Tech. Rep., Empresa de Pesquisa Energética (2023).

Secretaria de Desenvolvimento Econômico. O Projeto Sol de Minas. Tech. Rep., Secretaria de Desenvolvimento Econômico (2021).

Dantas, A. A. A., Carvalho, L. G. D. & Ferreira, E. Estimativa da radiação solar global para a região de lavras, mg. Ciência e Agrotecnologia 27, 1260–1263 (2003).

Barbosa, L. A. et al. Estimativa da radiação solar com base na temperatura do ar na região sul, suldeste, oeste de Minas e Campo das Vertentes. In XVII Congresso Brasileiro de Agrometeorologia, 2011 (Guarapari - ES, 2011).

Finzi, R. R. et al. Estimativa da radiação solar baseando-se na temperatura máxima e mínima do ar para a região noroeste de Minas Gerais. In XVII Congresso Brasileiro de Agrometeorologia, 2011 (Guarapari - ES, 2011).

Carvalho, F. J. et al. Avaliação de modelos de estimativa da radiação solar com base na temperatura do ar para o norte de Minas Gerais. In XVII Congresso Brasileiro de Agrometeorologia, 2011 (Guarapari - ES, 2011).

Paula, M. T. G. et al. Estimativa da radiação solar através dos valores de temperatura registrados na região nordeste de Minas Gerais. In XVII Congresso Brasileiro de Agrometeorologia, 2011 (Guarapari - ES, 2011).

Silva, C. R. D., Silva, V. J. D., Alves Júnior, J. & Carvalho, H. D. P. Radiação solar estimada com base na temperatura do ar para três regiões de minas gerais. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental 16, 281–288 (2012).

Silva, V. J. D., Silva, C. R. D., Finzi, R. R. & Dias, N. D. S. Métodos para estimar radiação solar na região noroeste de minas gerais. Ciência Rural 42, 276–282 (2012).

Ramos, J. P. A., Vianna, M. D. S. & Marin, F. R. Estimativa da radiação solar global baseada na amplitude térmica para o brasil. Agrometeoros 26, https://doi.org/10.31062/agrom.v26i1.26299 (2018).

Monteiro, A. F. M. & Martins, F. B. Global solar radiation models in Minas Gerais, Southeastern Brazil. Adv. Meteorol. 2019, 9515430. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9515430 (2019).

Moraes, R. A. & Miranda, W. L. Avaliação dos dados decendiais de precipitação, temperatura média, máxima e mínima do ar, radiação solar e evapotranspiração de referência simulados pelo modelo ecmwf para Minas Gerais. In XVIII Congresso Brasileiro de Agrometeorologia, 2013 (Belém - PA, 2013).

Lyra, G. B. et al. Estimates of monthly global solar irradiation using empirical models and artificial intelligence techniques based on air temperature in southeastern brazil. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 152, 1031–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-023-04442-z (2023).

Cunha, A. C., Filho, L. R. A. G., Tanaka, A. A. & Putti, F. F. Performance and estimation of solar radiation models in state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 7, 603–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-020-00956-x (2021).

Basílio, S. d. C. A., Putti, F. F., Cunha, A. C. & Goliatt, L. An evolutionary-assisted machine learning model for global solar radiation prediction in Minas Gerais region, southeastern Brazil. Earth Sci. Inform. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12145-023-00990-0 (2023).

Santos, P. A. B. d. et al. Machine learning and conventional methods for reference evapotranspiration estimation using limited-climatic-data scenarios. Agronomy. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13092366 (2023).

Tiba, C. et al. On the development of spatial/temporal solar radiation maps: A Minas Gerais (Brazilian) case study. J. Geogr. Inform. Syst. 06, 258–274. https://doi.org/10.4236/jgis.2014.63024 (2014).

Ministério de Minas e Energia. Potencial dos Recursos Energéticos no Horizonte 2050. Tech. Rep., Empresa de Pesquisa Energética (2018).

Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia (2022).

Liao, C. PyEarth: A lightweight python package for earth science (2024). Available at https://github.com/changliao1025/pyearth, version 0.1.26.

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Biomas do Brasil (2019). Available at http://www.ibge.gov.br.

Pysolar: staring directly at the sun since 2007 (2008).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Dolan, E. D. & Moré, J. J. Benchmarking optimization software with performance profiles. Math. Program. 91, 201–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s101070100263 (2002).

Basílio, S. d. C. A., Saporetti, C. M., Yaseen, Z. M. & Goliatt, L. Global horizontal irradiance modeling from environmental inputs using machine learning with automatic model selection: A case study in tanzania. Environmental Development 100766, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2022.100766 (2022).

Basílio, S. d. C. A., Silva, R. O., Saporetti, C. M. & Goliatt, L. Modeling global solar radiation using machine learning with model selection approach: A case study in tanzania. In Shakya, S., Ntalianis, K. & Kamel, K. A. (eds.) Mobile Computing and Sustainable Informatics, 155–168 (Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, 2022).

Huang, G.-B., Zhu, Q.-Y. & Siew, C.-K. Extreme learning machine: Theory and applications. Neurocomputing 70, 489–501, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2005.12.126 (2006). Neural Networks.

Wang, J., Lu, S., Wang, S.-H. & Zhang, Y.-D. A review on extreme learning machine. Multimed. Tools Appl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-021-11007-7 (2021).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–22 (2010).

Friedman, J. H. Multivariate adaptive regression splines. Ann. Stat. 1–67 (1991).

Cheng, M.-Y. & Cao, M.-T. Accurately predicting building energy performance using evolutionary multivariate adaptive regression splines. Appl. Soft Comput. 22, 178–188 (2014).

Ibrahem Ahmed Osman, A., Najah Ahmed, A., Chow, M. F., Feng Huang, Y. & El-Shafie, A. Extreme gradient boosting (xgboost) model to predict the groundwater levels in Selangor Malaysia. Ain Shams Eng. J. 12, 1545–1556 (2021).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785 (ACM, 2016).

Smola, A. J. & Schölkopf, B. A tutorial on support vector regression. Stat. Comput. 14, 199–222 (2004).

Attar, N. F., Sattari, M. T., Prasad, R. & Apaydin, H. Comprehensive review of solar radiation modeling based on artificial intelligence and optimization techniques: future concerns and considerations. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 25, 1079–1097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-022-02434-7 (2023).

Biscani, F. & Izzo, D. A parallel global multiobjective framework for optimization: Pagmo. J. Open Source Softw. 5, 2338 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by UFJF’s High-Speed Integrated Research Network (RePesq). https://www.repesq.ufjf.br/.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the support of the Computational Modeling Graduate Program at Federal University of Juiz de Fora (UFJF), the Federal Center for Technological Education of Minas Gerais (CEFET-MG), and the Brazilian funding agencies CNPq - Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (grants 429639/2016 and 401796/2021-3), FAPEMIG - Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (grant number APQ-00334/18), and CAPES - Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, (finance code 001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The development, execution and analysis of the proposed framework were performed by Samuel da Costa Alves Basílio and Leonardo Goliatt. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Samuel da Costa Alves Basílio. Cicero Manoel dos Santos, Alfeu Dias Martinho and Leonardo Goliatt commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

da Costa Alves Basílio, S., dos Santos, C.M., Martinho, A.D. et al. Transfer learning for solar irradiation prediction in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Sci Rep 15, 40235 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24095-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24095-4