Abstract

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has introduced new regulations aimed at reducing carbon emissions in the shipping industry. In this study, seven amines were combined with seven phase separation agents to screen three phase-change absorbents that demonstrated distinct phase separation following CO₂ absorption: DETA + n-Butanol + H₂O, DETA + NMP + H₂O, and DETA + DMSO + H₂O. Among these, the DETA + DMSO + H₂O phase-change absorbent outperformed the MEA-based absorbent in both CO₂ absorption capacity (3.17 mol CO₂/kg solvent) and desorption capacity (2.13 mol CO₂/kg solvent), corresponding to improvements of 46% and 12%, respectively. Furthermore, its regeneration energy consumption was only 29% that of MEA. These results demonstrate that the DETA + DMSO + H₂O absorbent offers efficient CO₂ capture performance alongside significant energy-saving potential, making it a promising candidate for onboard carbon capture applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increase in international economic exchange, the shipping industry, as the main mode of global trade, has expanded steadily. However, this growth has resulted in a pressing issue: rising carbon emissions from shipping now threaten the global climate. Many countries are actively working to reduce these emissions. In 2018, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) launched a greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction strategy. This strategy aims to cut shipping-related CO₂ emissions by at least 50% by 2050 relative to 2008 levels and achieve full decarbonization eventually. These policies have accelerated maritime decarbonization, making ship exhaust carbon management an emerging research priority.

Tavakolideng et al.1 investigated the feasibility of onboard carbon capture by systematically evaluating the technical viability of ship-based systems. They remained optimistic about future development, suggesting that 70–90% CO₂ capture could be achieved. Chemical absorption is currently the most widely used carbon capture technology in industry, mainly applied in coal-fired power plants. In contrast, onboard carbon capture remains at the research stage, with no real-ship applications to date. Therefore, researchers actively explore feasible methods for onboard carbon capture.

Among carbon capture technologies, liquid amine scrubbing remains the most mature and effective method regarding CO₂ absorption capacity. Liquid amine scrubbing separates CO₂ from gas streams through chemical reactions with amine compounds. Common amine absorbents include monoethanolamine (MEA), 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (AMP), and N-methyldiethanolamine (MDEA)2. A novel aqueous mixed solvent was developed by Dash et al.3 through combining AMP with 1-Methyl Piperazine (1MPZ). This solvent integrates the favorable thermodynamic equilibrium properties of AMP with the superior reaction kinetics of 1MPZ and exhibited a cyclic capacity higher than that of the benchmark 30 wt% MEA solution. In a subsequent study, Dash et al.4 conducted simulations using Aspen Plus, which revealed an enhanced CO₂ equilibrium solubility of MDEA solvent activated by PZ. Aspen Plus was further employed to simulate the CO₂ capture process in a coal-fired power plant, examining how absorber height and stripper pressure affect the reboiler heat duty and overall plant efficiency. The study found that supplying low-pressure steam reduced the plant’s energy loss by approximately 30%5. Additionally, Vamja et al.6 measured the density, viscosity, and surface tension of 1-MPZ solutions at varying temperatures, concentrations, and CO₂ loadings. The obtained data were subsequently fitted using relevant models to support the design of post-combustion CO₂ capture systems based on 1-MPZ.

In recent years, research on amine-based absorbents has been further expanded. Dey et al.7,8 developed various mathematical models to investigate the equilibrium solubility of a mixed solvent system comprising N-(3-aminopropyl)−1,3-propanediamine (APDA), MDEA, and AMP. In subsequent studies, they proposed a novel solvent system activated by APDA using 1-dimethylamino-2-propanol (DMA2P), which enhanced both CO₂ solubility and absorption characteristics. Shukla et al.9 investigated CO₂ capture using a rotating packed bed (RPB) and highlighted the absorption performance of conventional amines (MEA, AMP, MDEA, and PZ) under RPB operating conditions. In another study, they identified a mixed solvent comprising AMP, PZ, and 1-(2-aminoethyl) piperazine (AEP) as a potential candidate for post-combustion CO₂ capture (PCC), and employed machine learning to construct models that accurately predicted the solvent’s density, viscosity, and CO₂ solubility10. Darji et al.11 proposed a novel amine solvent, bis(3-aminopropyl)amine (APA), and determined its − ln Kₐ values at various temperatures. They further combined density functional theory (DFT) and natural bond orbital (NBO) calculations to elucidate the functional group effects on − ln Kₐ, and validated the results experimentally.

Recently, various amine-based absorbents with potential for onboard carbon capture have been developed as research advances. Zhou et al.12 used a blended amine absorbent (MEA + AMP) for CO₂ absorption and desorption. They found that a solution of 20% MEA and 10% AMP exhibited good CO₂ absorption, achieving desorption efficiency above 50% at 80% capture efficiency. Hosseini-Ardali et al.13 employed mixtures of piperazine (PZ) and methyl diethanolamine (MDEA) for CO₂ capture and optimized process parameters using evolutionary algorithms and multi-objective optimization. Luo et al.14 developed a novel cyclic process using a phase-change absorbent (diethylenetriamine (DETA) + sulfolane + H₂O) for CO₂ absorption. The new process achieved a cyclic loading 35% higher than that of a 30 wt% MEA solution.

Amines used in liquid amine scrubbing must be regenerated by heating after absorbing CO₂, which releases the captured CO₂ and restores their reactivity for cyclic use. However, this necessary process typically requires high temperatures (393.15–423.15 K), leading to considerable energy consumption, which remains a major limitation for large-scale industrial application of liquid amine scrubbing15. To address this issue, researchers have recently attempted to reduce regeneration energy consumption by optimizing absorbent formulations, improving regeneration processes, and developing novel amine-based absorbent systems.

Li et al.16 proposed a novel metal-mediated amine regeneration (MMAR) method that reduces the enthalpy of the CO₂ reaction via reversible complexation between amines and metal ions, thereby lowering the regeneration energy requirement. Li et al.17 also developed a series of ternary amine absorbents, finding that the DEEA + PZ + PD system exhibited high CO₂ loading capacity (0.988 mol CO₂/mol amine) and low regeneration energy (2.688 GJ/t CO₂), significantly outperforming single and binary amine systems. Valluri et al.18 investigated bipolar membrane electrodialysis (EDBM) technology for reducing solvent regeneration energy during CO₂ capture. They found that, compared with traditional thermal regeneration, EDBM could lower regeneration energy to as little as 1.18 MJ/kg CO₂, significantly less than the 3–4 MJ/kg CO₂ required by thermal methods. Additionally, alkaline absorbents such as sodium carbonate and sodium hydroxide can further reduce costs and energy consumption.

Phase-change absorbents represent a novel class of CO₂ capture solvents that have attracted significant attention because they reduce regeneration energy consumption. These absorbents exhibit unique phase-change behavior: after CO₂ absorption, they separate into a CO₂-rich phase and a lean phase containing only trace amounts of CO₂. Regenerating only the CO₂-rich phase significantly reduces the overall energy consumption for regeneration.

Hu et al.19 developed a novel phase-change absorbent, MEA + n-butanol + H₂O (MNBH), which achieved a CO₂ desorption efficiency of 89.96% at 393.15 K, with a regeneration energy of 2.6 GJ/t CO₂, approximately 35% lower than that of conventional 30% MEA. Hong et al.20 proposed a new phase-change absorbent, MAE + DGM + H₂O. Experimental results showed that its regeneration energy consumption was only 2.28 GJ/t CO₂, significantly lower than that of conventional 30% MEA. Fang et al.21 proposed a novel anhydrous solid–liquid phase-change absorbent, DAP-NPA. By introducing AMP and piperazine (PZ) as absorption promoters, they significantly shortened saturation time and further reduced regeneration energy to 1.30 GJ/t CO₂ and 1.35 GJ/t CO₂, corresponding to only 34.2% and 35.6% of that required by conventional 5 M MEA. These phase-change absorbents have demonstrated excellent potential for reducing regeneration energy consumption.

Although conventional amine solvents, such as monoethanolamine (MEA), have been extensively studied for CO₂ capture, their application in ship exhaust gas treatment remains challenging due to high regeneration energy requirements and limited onboard space. In contrast, phase-change absorbents have attracted growing interest because they combine high CO₂ absorption capacity with low regeneration energy. Nevertheless, a systematic evaluation of phase-change absorbents under ship exhaust gas conditions is still lacking. To address this gap, the present study aims to assess a series of phase-change amine absorbents and to identify the most promising candidates for efficient and low-energy CO₂ capture from ship exhaust.

This study aims to develop novel phase-change absorbents that have the potential to reduce regeneration energy consumption. Combinations of seven different amines and six phase-separation promoters were screened to identify phase-change absorbents capable of successful phase separation and effective CO₂ absorption. The CO₂ absorption and desorption performance, as well as regeneration energy consumption, were experimentally investigated. The results were compared with those of conventional 5 M MEA to evaluate the potential for energy saving. This work provides important insights into the development of novel phase-change absorbent formulations with significant potential for energy saving.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

In this study, 5 M ethanolamine (MEA, ≥ 99%, Macklin) was used as the benchmark absorbent. Several amines previously reported to exhibit good CO₂ absorption capacity were selected as the primary absorbents, including diethylethanolamine (DEEA, ≥ 99%, Macklin), 2-((2-aminoethyl)amino)ethanol (AEEA, 99%, Macklin), diethylenetriamine (DETA, ≥ 99%, Macklin), 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (AMP, ≥ 99%, Macklin), 3-dimethylaminopropylamine (DMAPA, 99%, Macklin), and methyldiethanolamine (MDEA, ≥ 99%, Macklin). In addition, six compounds were selected as phase-separation promoters: DEEA, N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, ≥ 99%, Macklin), n-butanol (≥ 99%, Macklin), tetrahydrofuran (THF, ≥ 99%, Macklin), isopropyl alcohol (IPA, ≥ 99%, Macklin), and triethylene glycol (TEG, ≥ 99%, Macklin). High-purity carbon dioxide and nitrogen gas (99.99%) were supplied by Zhanjiang Shiji Shuanglong Industrial Gases Co., Ltd. (China). All amine solutions were prepared using deionized (DI) water.

Experimental procedure

CO2 absorption experiment

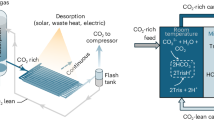

The CO₂ absorption experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 1. Single-amine absorbents were prepared at a fixed mass of 25 g with a concentration of 5 M. Mixed amine absorbents were formulated at a fixed mass ratio of amine: phase-separation agent: water = 3:3:4. The prepared absorbents were transferred into a three-necked flask, heated to 40 °C in a water bath, and stirred at 100 rpm.

Prior to CO₂ absorption, the system was purged with high-purity N₂ until the CO₂ concentration at the outlet, measured using a gas analyzer (PG-350, ± 2%, HORIBA Trading Co., Ltd., China), reached 0%. Simulated marine engine exhaust gas was then introduced to initiate the absorption process. The simulated exhaust was assumed to be free of SOₓ and NOₓ and consisted primarily of N₂ and CO₂, with a total gas flow rate maintained at 1000 mL/min. The CO₂ concentration in the gas stream was set at 5 vol%, corresponding to typical concentrations found in marine engine exhaust22. Gas was introduced into the absorbent via bubbling to facilitate efficient gas–liquid contact and CO₂ absorption.

The absorption experiment was terminated when the outlet CO₂ concentration reached 4.75 vol%, corresponding to 95% CO₂ loading and indicating near saturation. For phase-change absorbents, the CO₂-rich and CO₂-lean phases were separated using a separatory funnel. The CO₂ loading in each phase was subsequently determined via acid–base titration.

CO2 desorption experiment

After the absorption experiment, the CO₂-loaded absorbent was transferred to the desorption apparatus, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The desorption was conducted at a fixed temperature of 403.15 K, with continuous stirring at 100 rpm to facilitate efficient CO₂ release. The desorption process was deemed complete when no further bubbles were observed in the gas-washing bottle, at which point the experiment was terminated and the corresponding electrical energy consumption was recorded. In this study, all regeneration experiments were conducted under identical operating conditions, and the experimental setup was well insulated to minimize heat losses. The regeneration energy consumption was calculated based on the assumption that the electrical energy supplied by the heater is primarily used for solvent regeneration, an approach that has been widely adopted in previous studies on regeneration energy assessment23–26。 Subsequently, samples of the absorbent were collected and subjected to acid-base titration to determine the residual CO₂ loading. The mass of each sample was recorded, and each titration was performed in duplicate to ensure accuracy.

All experiments in this study were independently repeated at least three times under identical conditions. The reported results represent the mean values, and standard deviations were calculated to quantify experimental uncertainty. CO₂ loadings were determined by acid–base titration, with each sample titrated at least three times and the average value reported. The relative standard deviations of the experimental data were generally below 5%.

Parameters involved

During the absorption process, the CO₂/N₂ gas mixture enters the reactor, where only CO₂ participates in the chemical reaction with the absorbent. As nitrogen is inert under the experimental conditions, its flow rate is assumed to remain unchanged at both the inlet and outlet. Based on this assumption, key performance metrics—including CO₂ absorption rate, loading capacity, absorption efficiency, desorption capacity, and desorption efficiency—were calculated.

The CO₂ absorption rate \({r_{{\text{abs}}}}(t)\) of the absorbent at time t was calculated using Eq. (1).

where \({q_{{\text{C}}{{\text{O}}_{{\text{2,in}}}}}}\) is the molar flow rate of CO₂ at the inlet of the absorption reactor, and \({q_{{\text{C}}{{\text{O}}_{{\text{2,out}}}}}}\) is the molar flow rate of CO₂ at the outlet.

The molar flow rate of CO₂ at the reactor outlet, denoted as\({q_{{\text{C}}{{\text{O}}_{{\text{2,out}}}}}}\), can be calculated using Eq. (2).

Here, \({C_{{\text{C}}{{\text{O}}_{{\text{2,out}}}}}}\)represents the CO₂ volume fraction measured by the gas analyzer; \({V_{\text{m}}}\)is the molar volume of the gas, assumed to be 24.7 L/mol at 25 °C and 0.1 MPa; and \({Q_{{{\text{N}}_{\text{2}}}}}\)denotes the volumetric flow rate of nitrogen.

The molar flow rate of CO₂ at the inlet of the absorption reactor, \({q_{{\text{C}}{{\text{O}}_{{\text{2,in}}}}}}\), can be calculated using Eq. (3).

where \({Q_{{\text{C}}{{\text{O}}_{{\text{2,in}}}}}}\) is the volumetric flow rate of CO₂ at the reactor inlet.

The cumulative CO₂ loading of the absorbent from time 0 to time t can be calculated using Eq. (4).

where \(\Delta t\) is the time interval between gas analyzer measurements.

The relative CO₂ loading \(R'(t)\) of the absorbent from time 0 to time t can be calculated using Eq. (5).

where n(mol) is the amount of solute in the absorbent.

The CO₂ desorption capacity \({R_{\text{d}}}\) can be calculated using Eq. (6).

where \({C_{{\text{before}}}}\) is the titration reading before desorption, \({C_{{\text{after}}}}\) is the titration reading after desorption, and \(m'\) is the mass of the absorbent sample.

The phase split ratio, \({R_{{\text{phase}}}}\), of the phase-change absorbent is defined as the percentage of the volume of the rich phase relative to the total volume of the absorbent, and it can be calculated using Eq. (7).

Here, \({V_{{\text{rich}}}}\)represents the volume of the rich phase of the absorbent, and \({V_{{\text{lean}}}}\)represents the volume of the lean phase.

The total CO₂ loading of the solvent, \({R_{\text{T}}}\), represents the combined CO₂ content of both the upper and lower phases and can be calculated using Eq. (8).

Here, \({R_{\text{U}}}\) and\({R_{\text{L}}}\) denote the CO₂ loadings in the upper and lower phases, respectively;\({m_{\text{U}}}\) and\({m_{\text{L}}}\) denote the masses of the solvent in the upper and lower phases, respectively; and\({m_{\text{T}}}\) denotes the total mass of the solvent.

The regeneration energy consumption of the absorbent (H, kJ/mol) is a key performance indicator, defined as the ratio of the heat input to the amount of CO₂ released, with the energy input measured by an electric meter. The regeneration energy consumption can be calculated using Eq. (8). Similar calculation methods have been reported by Zhou et al.12 and Zhang et al.24.

Here, H represents the regeneration energy consumption in kJ/mol, E is the electric meter reading in kW·h, and \({n_{{\text{C}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}}}\)is the amount of CO₂ released during the desorption experiment.

The relative regeneration energy consumption (\(RH\), kJ/mol) is defined as the ratio of the regeneration energy consumption of the mixed amine solution to that of MEA, and is calculated using Eq. (9).

where \({H_{\text{i}}}\)is the regeneration energy consumption of the mixed amine solution (kJ/mol), and \({H_{\text{b}}}\)is the regeneration energy consumption of the 5 M MEA solution (kJ/mol).

Results

Screening of absorbents

To develop CO₂ absorbents with high absorption efficiency, six amine compounds listed in Table 1 were selected for screening. These compounds have been previously confirmed to exhibit good CO₂ absorption performance. DEEA, DMAPA, and MDEA have been widely validated in industrial applications and show excellent CO₂ absorption capacities27,28. The unique molecular structure of AEEA provides additional amino groups, which enhance its CO₂ absorption capacity. The polyamine structure of DETA enables the formation of stable complexes with CO₂, thereby improving absorption efficiency29. AMP is a sterically hindered amine that shows high selectivity for CO₂ at low temperatures30. The favorable CO₂ absorption characteristics of these absorbents suggest their potential as primary absorbents in phase-change systems.Up to three levels of subheading are permitted. Subheadings should not be numbered.

According to Table 1, DETA exhibits a saturated CO₂ capacity of 1.05 mol CO₂ per mol amine, which represents a 102% increase compared to MEA (0.52 mol CO₂ per mol amine). The superior CO₂ loading capacity of DETA is attributed to its molecular structure, which contains three amine groups—two primary amines (–NH₂) and one secondary amine (–NH)—providing additional active sites for CO₂ binding. Theoretically, 1 mol of DETA can react with up to 3 mol of CO₂. However, the actual CO₂ uptake is lower than the theoretical maximum due to reaction reversibility and incomplete participation of DETA.

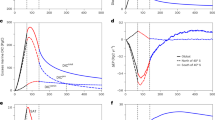

Figure 3 shows the CO₂ absorption capacity and absorption rate of the single amine absorbents. As illustrated in Fig. 3(a), at 100 min of experimental time, DETA shows the highest CO₂ loading among the seven absorbents, reaching 0.71 mol CO₂ per mol amine, which is significantly higher than the others. This value is 11% higher than DMAPA (0.64 mol CO₂ per mol amine), the second highest, and 39% higher than MEA (0.51 mol CO₂ per mol amine).

According to Fig. 3(b), the CO₂ absorption rate of DETA remains higher than that of the other six absorbents after 40 min. The relatively lower absorption rate during the first 40 min may result from insufficient mixing of CO₂ with the solution and incomplete reaction initiation. Ye et al.31 reported that the secondary amine group of DETA also participates in the reaction, providing additional CO₂ binding sites. The potential reactions between DETA (denoted as A) and CO₂ are presented in Eqs. (10)–(14).

Formation of primary carbamate:

Formation of secondary carbamate:

Formation of primary–primary dicarbamate:

Formation of primary–secondary dicarbamate:

Formation of tricarbamate:

The reactions between DETA and CO₂ show that both secondary and primary amine groups of DETA participate in carbamate formation, providing multiple reactive sites. Due to the reversibility of these reactions, the carbamates formed are unstable, and four types of carbamate species coexist in the solution, resulting in a complex solute composition system32,33. The excellent CO₂ absorption performance of DETA indicates its great potential as the primary active component in phase-change absorbents.

Screening of phase separators

To enable successful phase separation following CO₂ absorption by the DETA-based absorbent, phase separation promoters were screened. Seven phase separation promoters with experimentally validated separation-enhancing effects were selected in this study34,35,36,37,38,39. For each combination, the mass ratio of amine to phase separation promoter to H₂O was fixed at 3:3:4, with a total solution mass of 25 g and an absorption temperature of 313.15 K. Figure 4 shows the CO₂ absorption capacities and absorption rates of the different absorbents.

Table 2 shows that only three absorbent systems—DETA + n-Butanol + H₂O (DTNB), DETA + NMP + H₂O (DTNP), and DETA + DMSO + H₂O (DTSO)—successfully exhibited phase separation after CO₂ absorption. Figure 4(a) shows that the CO₂ absorption capacity of DTSO approached saturation at 3.17 mol CO₂/kg solvent, outperforming other absorbent combinations and representing a 46% improvement over 5 M MEA (2.17 mol CO₂/kg solvent). DTSO also exhibited a faster absorption rate during the first 30 min compared to other absorbents, although the rates converged at later stages. Figure 4(b) further illustrates that DTSO had the highest absorption rate during the first 20 min, followed by a gradual decrease. After 80 min, absorption nearly reached saturation, and minimal differences were observed in absorption rates among the various combinations.

The DTSO system exhibited the highest initial CO₂ absorption rate, whereas the kinetics of the DTNP and DTNB systems were slower, indicating that interactions between CO₂ and the DTSO solvent are more favorable, possibly due to stronger polarity and enhanced mass transfer in the biphasic environment. The CO₂ absorption rates of all solvent systems gradually decreased over time, as the active sites available for CO₂ capture were progressively occupied, reducing the absorption driving force and eventually approaching a steady state, which indicates equilibrium.

During the initial stage, the CO₂ absorption rate in DMSO exceeded 25 × 10⁻⁶ mol/s, while solvents such as NMP, n-butanol, and IPA also showed relatively high initial rates. In contrast, TEG exhibited a comparatively lower initial rate. These results demonstrate that different solvents display distinct initial absorption kinetics, with solvents like DMSO facilitating more rapid CO₂ uptake. Over time, the absorption rates of all solvents gradually declined and converged.

Solvents can also influence the activation energy of the reaction between CO₂ and amines. Those that reduce the activation energy promote faster reactions and higher absorption rates. In particular, DMSO may lower the activation energy through solvation effects, leading to higher initial CO₂ absorption rates. As the reaction progresses, the number of available reactive sites decreases, causing a corresponding decline in absorption rate, consistent with the observed macroscopic trend. Compared with other systems, the higher CO₂ loading and faster absorption rate of DTSO further highlight its potential advantages for rapid onboard CO₂ capture.

Desorption capacity and regeneration energy consumption of phase-change absorbents

Based on previous studies, three phase-change absorbents capable of phase separation were obtained. Their desorption performances are compared in this section. The desorption temperature for all three phase-change absorbents was uniformly set at 403.15 K, and desorption was conducted solely on the rich phase. Figure 5 shows that among the three phase-change absorbents, DTSO exhibited the highest desorption capacity, reaching 2.13 mol CO₂/kg solvent, equivalent to 112% of the MEA absorbent’s capacity (1.90 mol CO₂/kg solvent). The desorption capacities of DTNB and DTNP were 1.28 mol CO₂/kg solvent and 1.48 mol CO₂/kg solvent, corresponding to 67% and 78% of the MEA absorbent’s capacity, respectively. DTSO has the highest desorption capacity and is the only phase-change absorbent that surpasses MEA.

The desorption energy consumption of three phase-change absorbents was investigated and compared with that of MEA. Figure 6(a) shows that among the three absorbents, DTSO exhibited the lowest regeneration energy consumption at 6177.87 kJ/mol CO₂, corresponding to only 29% of that of MEA. In contrast, DTNB showed the highest regeneration energy consumption of 15,230.27 kJ/mol CO₂, accounting for 70% of that of MEA. These results indicate that the DTSO phase-change absorbent has the greatest potential for energy savings. The observed reduction in total regeneration energy arises from two complementary process advantages. First, phase separation reduces the volume of material that requires heating: after CO₂ absorption, the solution spontaneously separates into a CO₂-rich phase and a CO₂-lean phase, with only the CO₂-rich phase requiring heating, while the lean phase can be directly recycled without additional energy input. Second, the elevated temperature accelerates desorption, thereby shortening the heating time: raising the temperature to 130 °C significantly increases the CO₂ desorption rate, reducing the overall regeneration duration. Since energy consumption was evaluated based on the actual operating time of the electric heater, the shorter operation time directly results in lower electricity use. Consequently, the total regeneration energy remains lower than that of MEA. Although the slight increase in temperature may marginally raise the instantaneous energy demand per unit mass of solution, the combined effect of reduced solvent volume requiring regeneration and shortened heating time leads to substantial potential energy savings.

Discussion

In this study, seven amine blended systems were screened to identify the most efficient formulation, rather than suggesting that all amines should be used simultaneously in practical applications. For large-scale deployment, only the best-performing system, such as DTSO, would be employed. Both DETA and DMSO are commercially available and reasonably priced, and the substantial reduction in regeneration energy consumption—only 29% of that of MEA—implies significant operational cost savings over long-term use. Although a comprehensive techno-economic analysis (TEA) under actual ship operating conditions is still required to provide a quantitative cost assessment, the application of the DTSO phase-change absorbent system is considered economically feasible.

A comprehensive analysis of the experimental results from Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6 indicates that the DETA + DMSO + H₂O (DTSO) system exhibits the best overall performance across multiple key metrics. Its CO₂ absorption capacity reaches 3.17 mol/kg, significantly higher than that of DTNB (3.03 mol/kg), DTNP (2.93 mol/kg), and the benchmark MEA (2.17 mol/kg), representing an increase of 46%. Regarding desorption performance, DTSO also stands out, with a desorption capacity of 2.13 mol/kg, surpassing DTNB (1.28 mol/kg) and DTNP (1.48 mol/kg), and exceeding MEA (1.90 mol/kg) by 12%. The most notable advantage of DTSO is its extremely low regeneration energy, only 6177.87 kJ/mol CO₂, corresponding to 29% of that of MEA and far lower than the energy consumption of DTNB (15,230.27 kJ/mol CO₂) and DTNP(14139.17 kJ/mol CO₂). Furthermore, from the perspective of absorption kinetics, DTSO demonstrates a relatively rapid initial CO₂ uptake. Therefore, considering the three core indicators of absorption capacity, desorption efficiency, and regeneration energy, the DTSO system exhibits the highest energy efficiency and application potential among all the solvents screened in this study.

Although the DETA + DMSO + H₂O (DTSO) system demonstrates excellent CO₂ capture performance, several potential challenges and limitations must be considered before its practical application on ships. First, solvent cost and environmental impact are important practical concerns. As an efficient phase-separation promoter, DMSO is generally more expensive than conventional MEA and exhibits certain volatility and toxicity. This not only increases the initial investment and operational costs but also imposes stricter requirements on onboard operational safety, personnel health protection, and exhaust gas treatment. Second, material compatibility represents another critical engineering issue. Amine solutions are inherently corrosive, and DMSO, as a strongly polar solvent, may cause swelling or degradation of certain polymeric materials, such as seals and pipe linings. This necessitates careful material selection and compatibility testing during system design, potentially leading to additional equipment costs. Furthermore, the unavoidable motion and vibration of ships during navigation may affect the phase separation efficiency and stability of the DTSO system, posing dynamic operating challenges that are difficult to fully replicate under static laboratory conditions. Future research should focus on developing novel phase-change solvents with lower cost and reduced environmental impact, as well as conducting comprehensive evaluations of the dynamic performance and engineering optimization of the DTSO system under specific ship operating conditions.

Conclusion

This study systematically evaluated the performance of various amine-based solvent systems for shipborne carbon capture and identified three promising phase-change absorbent systems: DTSO, DTNB, and DTNP. Among these, DTSO exhibited the best absorption and desorption performance, significantly lowering the desorption energy consumption. Compared to the conventional MEA absorbent, DTSO improved the CO₂ absorption capacity by 46%, reaching 3.17 mol CO₂/kg solvent, and increased the desorption capacity by 12% to 2.13 mol CO₂/kg solvent. Meanwhile, its desorption energy consumption was only 29% of that of MEA, demonstrating remarkable energy-saving potential. These results indicate that the DETA + DMSO + H₂O phase-change absorbent system holds strong potential as a next-generation absorbent for shipborne carbon capture, providing a promising solution to overcome the energy consumption bottleneck of traditional amine scrubbing. This work provides a novel energy-efficient CO₂ absorption strategy for ship carbon capture.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tavakoli, S. et al. Exploring the technical feasibility of carbon capture onboard ships. J. Clean. Prod. 452, 142032 (2024).

Wilberforce, T., Olabi, A. G., Sayed, E. T. & Elsaid, K. Abdelkareem, M. A. Progress in carbon capture technologies. Sci. Total Environ. 761, 143203 (2021).

Dash, S. K., Parikh, R. & Kaul, D. Development of efficient absorbent for CO2 capture process based on (AMP + 1MPZ). Materials Today: Proceedings 62, 7072–7076 (2022).

Dash, S. K., Mondal, B. K., Samanta, A. N. & Bandyopadhyay, S. S. Post-Combustion CO2 Capture with Sulfolane Based Activated Alkanolamine Solvent. in Computer Aided Chemical Engineering (eds. Gernaey, K. V., Huusom, J. K. & Gani, R.) vol. 37 521–526 (Elsevier, 2015).

Dash, S. Retrofitting a CO2 capture unit with a coal based power Plant, process simulation and parametric study. J. Clean. Energy Technol. https://doi.org/10.18178/JOCET.2017.5.3.377 (2024).

Vamja, V., Shukla, C., Bandyopadhyay, R. & Dash, S. K. Density, Viscosity, and surface tension of aqueous 1-Methylpiperazine and its carbonated solvents for the CO2 capture process. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 69, 904–914 (2024).

Dey, A., Dash, S. K. & Mandal, B. Elucidating the performance of (N-(3-aminopropyl)-1, 3-propanediamine) activated (1- dimethylamino-2-propanol) as a novel amine formulation for post combustion carbon dioxide capture. Fuel 277, 118209 (2020).

Dey, A., Mandal, B. & Dash, S. K. Analysis of equilibrium CO2 solubility in aqueous APDA and its potential blends with AMP/MDEA for postcombustion CO2 capture. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.5404

Shukla, C., Mishra, P. & Dash, S. K. A review of process intensified CO2 capture in RPB for sustainability and contribution to industrial net zero. Front Energy Res 11, 1135188 (2023).

Shukla, C., Mishra, P., Dubey, R. & Dash, S. K. CO2 solubility and physicochemical properties of 2-amino 2-methyl-1-propanol based solvents for post-combustion CO2 capture. Predictive modeling using machine learning. J. Mol. Liq. 415, 126327 (2024).

Darji, M., Manhas, A., Dash, S. K. & Mukherjee, K. Dissociation constants of amine solvents used in CO2 capture: titrimetric Estimation and density functional theory calculation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 62, 7868–7876 (2023).

Zhou, J., Zhang, J., Jiang, G. & Xie, K. Study on shipboard carbon capture technology with the MEA-AMP-Mixed absorbent based on ship applicability perspective. ACS Omega. 9, 35929–35936 (2024).

Hosseini-Ardali, S. M., Hazrati-Kalbibaki, M., Fattahi, M. & Lezsovits, F. Multi-objective optimization of post combustion CO2 capture using Methyldiethanolamine (MDEA) and piperazine (PZ) bi-solvent. Energy 211, 119035 (2020).

Luo, W., Guo, D., Zheng, J., Gao, S. & Chen, J. CO2 absorption using biphasic solvent: blends of diethylenetriamine, sulfolane, and water. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 53, 141–148 (2016).

Cristina Why MOFs outperform amine scrubbing? https://blog.novomof.com/why-mofs-outperform-amine-scrubbing

Li, K. et al. Mechanism investigation of advanced Metal–Ion–Mediated amine regeneration: A novel pathway to reducing CO2 reaction enthalpy in amine-Based CO2 capture. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 14538–14546 (2018).

Li, G. et al. Novel tri-solvent amines absorption for flue gas CO2 capture: efficient absorption and regeneration with low energy consumption. Chem. Eng. J. 493, 152699 (2024).

Valluri, S. & Kawatra, S. K. Reduced reagent regeneration energy for CO2 capture with bipolar membrane electrodialysis. Fuel Process. Technol. 213, 106691 (2021).

Hu, Y. et al. Experimental study on CO2 capture by MEA/n-butanol/H2O phase change absorbent. RSC Adv. 14, 3146–3157 (2024).

Hong, S. et al. A low energy-consuming phase change absorbent of MAE/DGM/H2O for CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. J. 480, 148079 (2024).

Fang, J. et al. Regulating the absorption and solid regeneration performance of a novel anhydrous solid–liquid phase change absorbent for carbon capture. Fuel 366, 131424 (2024).

CIMAC Recommendation No. 28. https://www.cimac.com/publications/recommendations410/cimac-recommendation-no.-28.html

Zhou, S. et al. Research on CO2 capture performance and reaction mechanism using newly tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA) monoethanolamine (MEA) mixed absorbent for onboard application. Chem. Eng. J. 485, 149790 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Reduction of energy requirement of CO2 desorption from a rich CO2-loaded MEA solution by using solid acid catalysts. Appl. Energy. 202, 673–684 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Reducing energy consumption of CO2 desorption in CO2-loaded aqueous amine solution using Al2O3/HZSM-5 bifunctional catalysts. Appl. Energy. 229, 562–576 (2018).

Zhu, Y. et al. Research on CO2 capture performance and reaction mechanism using a novel low energy consumption and high Cyclic performance absorbent for onboard application. J. Clean. Prod. 479, 144003 (2024).

Guo, H., Hui, L. & Shen, S. Monoethanolamine + 2-methoxyethanol mixtures for CO2 capture: Density, viscosity and CO2 solubility. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 132, 155–163 (2019).

Liu, F., Rochelle, G. T., Fang, M. & Wang, T. Volatility of 2-(diethylamino)-ethanol and 2-((2-aminoethyl) amino) ethanol, a biphasic solvent for CO2 capture. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 106, 103257 (2021).

Zhai, W. et al. Fundamental physicochemical properties, intermolecular interactions and CO2 absorption properties of binary mixed solutions of monoethanolamine + diethylenetriamine. J. Mol. Liq. 413, 125974 (2024).

Karunarathne, S. S., Eimer, D. A. & Øi, L. E. Density, viscosity and free energy of activation for viscous flow of CO2 loaded 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (AMP), monoethanol amine (MEA) and H2O mixtures. J. Mol. Liq. 311, 113286 (2020).

Ye, Q., Zhu, L., Wang, X. & Lu, Y. On the mechanisms of CO2 absorption and desorption with phase transitional solvents. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 56, 278–288 (2017).

Nwaoha, C. et al. Carbon dioxide (CO2) capture performance of aqueous tri-solvent blends containing 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (AMP) and Methyldiethanolamine (MDEA) promoted by diethylenetriamine (DETA). Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 53, 292–304 (2016).

Sun, Y. et al. Microwave-assisted one-pot synthesis of hierarchical MnCO3/NiO heterojunction with superior energy storage performance for aqueous supercapacitor. Chem. Eng. J. 519, 165031 (2025).

Liu, J., Qian, J. & He, Y. Water-lean triethylenetetramine/N,N-diethylethanolamine/n-propanol biphasic solvents: Phase-separation performance and mechanism for CO2 capture. Sep. Purif. Technol. 289, 120740 (2022).

Eskandari, M., Elhambakhsh, A., Rasaie, M., Keshavarz, P. & Mowla, D. Absorption of carbon dioxide in mixture of N-Methyl-2-Pyrrolidone and six different chemical solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 364, 119939 (2022).

Wang, N. et al. New insight and evaluation of secondary Amine/N-butanol biphasic solutions for CO2 capture: equilibrium Solubility, phase separation Behavior, absorption Rate, desorption Rate, energy consumption and ion species. Chem. Eng. J. 431, 133912 (2022).

Ibeh, S. & Jaeger, P. Interfacial tension of tri-ethylene glycol-water mixtures in carbon dioxide at elevated pressures. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol. 13, 1379–1390 (2023).

Herslund, P. J., Thomsen, K. & Abildskov, J. Solms, N. Modelling of tetrahydrofuran promoted gas hydrate systems for carbon dioxide capture processes. Fluid. Phase. Equilibria. 375, 45–65 (2014). von.

Jung, Y. T. & Diosady, L. L. Application of a ternary phase diagram to the phase separation of Oil-in-Water emulsions using isopropyl alcohol. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 89, 2127–2134 (2012).

Funding

Special Funds for Marine Economic Development of Guangdong Province (NO. GDNRC [2023]51).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.J. designed and constructed the experimental setup, performed absorption, desorption, and cyclic tests, analysed the data, and drafted the manuscript; J.H. assisted with experiments and contributed to manuscript preparation; C.S. conceived the research idea, supervised the project, and served as the corresponding author; S.Z., W.W., and K.Z. contributed to data analysis, figure preparation, language editing, and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, W., Hu, J., Sun, C. et al. Low-energy phase-change absorbents for efficient onboard CO₂ capture in the maritime sector. Sci Rep 15, 40318 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24126-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24126-0