Abstract

This paper presents a novel quadratic boost switched capacitor (SC) nine-level inverter topology designed for renewable energy applications, particularly photovoltaic (PV) systems. The proposed topology achieves high voltage gain through a quadratic boost mechanism combined with an optimized SC network. It features a reduced number of power switches and capacitors, resulting in a lower component count, enhanced reliability, and a more compact structure. After testing with a 350 VA load, the inverter achieved a peak efficiency of 96.7%, demonstrating its exceptional power conversion capabilities. A comprehensive comparison with existing SC-type nine-level inverter topologies is provided in terms of voltage gain, switch and capacitor count, and efficiency. The results confirm that the proposed inverter offers significant advantages, making it a strong candidate for next-generation PV systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, multilevel inverters (MLIs) have attracted significant attention in medium- and high-power applications due to their superior output waveform quality, reduced electromagnetic interference (EMI), and lower voltage stress on power switches compared to conventional two-level inverters1. Among various MLI configurations, switched-capacitor-based multilevel inverters (SCMLIs) have emerged as a promising alternative, particularly for applications requiring compactness and high efficiency. A key advantage of SCMLIs lies in the elimination of bulky magnetic components such as transformers and inductors2,3.

SCMLIs leverage passive capacitors and a reduced number of active switches to simultaneously boost the input DC voltage and synthesize multiple output voltage levels. This results in compact and lightweight architectures, making them particularly attractive for space-constrained and high-efficiency systems such as photovoltaic (PV) applications, fuel cell-powered devices, and electric vehicles (EVs)4. Through the careful design of capacitor charging and discharging paths, these inverters can achieve considerable voltage boosting, often eliminating the need for conventional DC–DC converters5.

Numerous SCMLI topologies have been proposed to improve voltage gain and reduce switch count. For example, the design in6 introduced a switched-capacitor inverter with moderate voltage gain and limited output levels, while7 proposed an enhanced topology with improved boosting capability at the cost of a more complex switching scheme. A nine-level SCMLI employing both active and passive switches was presented in4, demonstrating effective performance at low power levels. However, this topology lacked scalability for higher-power applications and exhibited a non-modular architecture. Moreover, its voltage gain was restricted due to the inherently linear nature of capacitor charging.

A self-balancing nine-level SCMLI with reduced total harmonic distortion (THD) was introduced in8, though its increased complexity with the number of voltage levels hindered modularity and practical implementation. Likewise, the step-up SCMLI reported in9 achieved self-voltage balancing but suffered from low voltage gain and high component count. A cascaded SCMLI topology was proposed in10 that eliminated the H-bridge but required multiple DC sources and switches, limiting its scalability. The topology in11 used a series-parallel SCMLI configuration with multiple H-bridge cells and isolated DC supplies, adversely affecting cost-effectiveness and modularity.

In12, a simplified seven-level inverter with a single DC source and two capacitors was introduced. Although it reduced hardware complexity, it only achieved a 0.5× voltage gain per capacitor, thus requiring high input DC voltages. The asymmetric SCMLI in13 employed multiple isolated DC links to increase voltage levels but provided only a fixed 1× gain per capacitor and introduced high voltage blocking stress on the switches.

To address these challenges, binary-boost topologies were introduced in14,15, achieving higher voltage gains by exponentially increasing the voltage across each capacitor. However, these designs resulted in large total standing voltage (TSV) and higher switch counts, which reduced overall efficiency and increased cost. To mitigate these issues, single-stage SCMLIs were explored in16,17,18, eliminating the H-bridge and using unipolar structures to achieve full output polarity.

While this simplified control and reduced TSV, most of these topologies delivered ≤ 1× gain per capacitor and required high-capacity voltage-rated capacitors to extend to higher voltage levels.

A nine-level SCMLI with an active neutral-point clamped (ANPC) configuration was introduced in19, using 10 switches and three capacitors. While it provided self-voltage balancing and moderate voltage gain (2×), its scalability remained limited. More recent nine-level designs, such as those in20,21, employed fewer switches but continued to rely on high-voltage capacitors, limiting modularity and increasing system cost.

A significant advancement was made in22 with the Nine-Level Quadruple Boost (NLQB) inverter, designed for EV applications. It achieved a 4× voltage gain using only 11 switches, 2 capacitors, and a diode, attaining 9.45% THD and 96.37% efficiency under a 786 W load. Compared to other SCMLIs, the NLQB inverter demonstrated reduced component count, minimized TSV, and enhanced cost-performance metrics. In23, a single-source nine-level SCMLI achieved a similar 4× gain with just 9 switches, 2 capacitors, and 2 diodes, while also ensuring continuous input current—an essential feature for PV-based systems.

Further innovations, such as the midpoint-clamped nine-level SCMLI in24, introduced soft-charging inductors between DC-link capacitors. However, the lack of anti-parallel diodes limited the inductor’s contribution to output regulation. Other topologies in25,26 achieved high efficiency (up to 96.2%) and demonstrated strong self-balancing behavior and low voltage ripple, though they required increased component complexity.

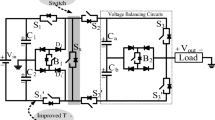

Further, several switched-capacitor multilevel inverter (SCMLI) topologies with generalized structures have been reported in27,28,29,30. The topology in27 introduces a common-ground transformerless inverter that minimizes leakage current in PV grid-connected systems. A five-level SCMLI with two switched capacitors and eight active switches is proposed in28, offering a voltage gain twice the input voltage. In29, a new seven-level SCMLI topology with a reduced device count is presented, where two switched capacitors are employed to achieve a seven-level output with a gain of three. Extending this idea, a quadratic-boost SCMLI for nine-level operation is introduced in30, using two capacitors with different voltage ratings. Although this topology improves upon29, it demands more devices, and the voltage stress on the switches equals the output voltage.

While more than a hundred SCMLI topologies have been published, this article emphasizes recent advances in nine-level inverter designs31,32. These works focus on quadratic-boost SCMLI structures to generate nine-level output waveforms. Similarly33, proposes an ANPC-based nine-level inverter with a reduced device count; however, its device requirement relative to the achieved voltage gain remains comparatively high. Moreover, these topologies still suffer from issues such as large component count and limited capacitor charging cycles.

To address these limitations, a novel SCMLI-based nine-level inverter topology is proposed in this work. In the proposed design, the sources are series-connected with switched-capacitor cells to realize the nine-level output voltage waveform. Although the topology achieves the desired voltage boosting capability, it requires a higher number of switches, and the associated voltage stress on the devices is significant.

This paper introduces a novel high-gain boost-type switched-capacitor nine-level inverter that combines simplicity, scalability, and high efficiency. The proposed topology delivers a quadratic voltage boost (up to 4×) from a single low-voltage DC source without relying on inductors or transformers, thereby ensuring magnetic-less operation. It is structurally compact, requiring only nine switches and two capacitors, which significantly reduces the total component count, switching complexity, and control overhead34. Unlike existing designs, the proposed inverter achieves self-voltage balancing across all capacitors, maintains low ripple voltage (< 5%), and operates stably across a wide modulation index and power factor range. Experimental validation under a 350 W load demonstrates a peak efficiency of 96.7%, confirming its superior performance and practical feasibility. These characteristics collectively make the proposed inverter topology a highly attractive solution for next-generation PV-fed and renewable energy systems, where size, simplicity, and efficiency are critical.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section:Description and modes of topology proposed introduces the proposed inverter topology, describing its circuit configuration and switching strategy. Section: Modulation techniques and component design presents a detailed analysis of the operating modes, including capacitor charging and discharging sequences for each output level. Besides, the modulation technique and component design considerations are discussed, with emphasis on level-shifted pulse-width modulation (LSPWM) and capacitor sizing methodology. In addition, this section evaluates various power loss mechanisms within the inverter, including conduction, switching, and ripple losses. Section: Results and Discussion provides simulation and experimental results to validate the inverter’s performance under different load and input conditions. Finally, the Conclusions Section concludes the paper by summarizing key findings and outlining future research directions.

Description and modes of topology proposed

Description of the proposed circuit

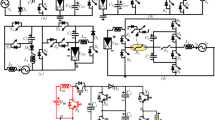

The proposed topology is derived from the well-known existing topologies presented in35,36, as shown in Fig. 1 (a) and (b). The proposed high-gain boost-type nine-level inverter topology is shown in Fig. 1 (c), which combines a reduced number of switches and capacitors with an efficient switched-capacitor structure. The system operates without inductors or transformers, achieving voltage boosting and polarity reversal solely through a coordinated switching strategy.

The switching states that produce the nine voltage levels are listed in Table 1, indicating the on-state switches, the resulting output voltage (vo), and the charging/discharging status of each capacitor. Capacitor activity is denoted by arrows: (↑) for charging and (↓) for discharging. Figure 2 illustrates the modes of operation during one complete cycle, including the positive half-cycle (Fig. 2b–e), negative half-cycle (Fig. 2g–j), and zero-output levels (Fig. 2a and f).

Detailed modes of operation of the switched-capacitor inverter

The proposed nine-level inverter operates through ten distinct switching modes, each producing a specific output voltage level by appropriately controlling the power switches and flying capacitors. These modes are categorized into zero, positive, and negative output levels, as detailed below.

The output voltage and capacitor charging/discharging actions for each mode are shown, corresponding to Fig. 2(a)–(j).

Zero-level modes

-

Mode 0 and Mode 5, Fig. 2a and f, vo = 0 vin: In these modes, the output voltage is zero. Mode 0 is achieved by turning ON switches S1’, Sab, S2, S3, and S4’, while Mode 5 is realized by activating S1, Sab, S2’, S3’, and S4.

-

In both cases, specific flying capacitors discharge C1 and C4 in Mode 0, or C2 and C3 in Mode 5, thereby establishing the reference zero level in the output voltage waveform.

Positive output levels

-

Mode 1, Fig. 2b, vo = + vin: to obtain the vin at the load under the non-unity power factor load, the current path is S1’, S2’, Sab, C2, S3’, C3 and S4. Also, the same mode of operation has an alternate switching path suitable for the unity power factor load only; the conducting switches are S1’, Sab, S2, S3’, and S4. During this mode, the capacitors C1 and C2 charge to vin.

-

Mode 2, Fig. 2c, vo = + vin + vC1: The same switch configuration as Mode 1 is used (S1’, Sab, S2, S3’, and S4), but the energy stored in C1 contributes to the output. Capacitors C1 and C2 discharge, transferring their energy to charge capacitor C3, resulting in an output voltage equal to the sum of vin and vC1.

-

Mode 3, Fig. 2d, vo = + vin + vC3: Switches S1’, S2, S2’, S3, and S4 are activated. The output combines vin and the voltage across capacitor C3. Capacitor C3 discharges to support the output, while C1 and C2 are recharged.

-

Mode 4, Fig. 2e, vo = + vin + vC1 + vC3: Switches S1’, Sab, S2, S3, and S4 are switched to produce the maximum positive output voltage level. The combined contributions of vin, vC1, and vC3 create this peak value. During this mode, C2 and C3 capacitors discharge to provide energy, and C4 begins charging in preparation for the negative half-cycle.

Negative output levels

-

Mode 6, Fig. 2g, vo = –(vC4 – vC1): Switches S1, Sab, S2, S3, and S4’ are turned ON, resulting in a negative output determined by the difference between –vC4 and + vC1. Capacitors C1 and C4 discharge simultaneously to supply energy to the load and establish a low negative level.

-

Mode 7, Fig. 2h, vo = –(vin + vC2): In this mode, switches S1, Sab, S2’, S3, and S4’are ON. The output voltage equals the sum of the source voltage and vC2, inverted in polarity. Capacitors C2 and C4 discharge, enabling the generation of a deeper negative level and maintaining waveform symmetry.

-

Mode 8, Fig. 2i, vo = –(vin + vC4): Switches S1, S2, S2’, S3’, and S4’ are activated, producing a significantly negative output formed by –vin and vC4. Capacitor C4 discharges to support the output, while capacitors C1 and C2 are recharged in preparation for the next positive cycle.

-

Mode 9, Fig. 2j, vo = –(vin + vC4 + vC2): This mode delivers the most negative output voltage by turning ON switches S1’, Sab, S2’, S3’, S4’. The output is the cumulative voltage of –vin, vC4, and vC2. Capacitors C2 and C4 discharge to deliver the required energy, while C3 charges for future use. This mode complements Mode 4 and forms the negative peak of the nine-level waveform.

Modulation techniques and component design

Conventional level-shifted modulation and pulse generation

The operating principle and control methodology of the proposed nine-level SCMLI are illustrated in Fig. 3. The control strategy employs level-shifted pulse width modulation (LSPWM) combined with a capacitor voltage balancing technique to regulate the output voltage waveform.

As shown in Fig. 3a, the modulation scheme compares a sinusoidal reference signal with eight level-shifted triangular carrier signals. This comparison produces gate pulses that determine the switching states of the inverter. The resultant waveform approximates a sinusoid using discrete voltage levels ranging from − 4Vdc to + 4Vdc, yielding a nine-level staircase output.

Furthermore, Fig. 3a includes a capacitor charge–discharge status table, indicating the behavior of each flying capacitor at different output levels. At any given level, a capacitor may be in one of three states: charging (C), discharging (DC), or neutral (NE). This balancing mechanism ensures that all capacitors maintain voltage levels within their designed thresholds, preventing overvoltage or undervoltage conditions.

In Fig. 3b, the gate signal generation logic is shown. Binary signals X1–X4 and Y1–Y4, along with their complements, are derived by comparing the reference sinusoid with each carrier waveform. These signals are processed through combinational logic circuits, primarily OR gates, to generate the final gate pulses for switches S1–S4 and their complements. This approach ensures accurate switching sequences for each voltage level while preserving capacitor voltage balance.

The proposed LSPWM strategy enhances the quality of the output waveform, reduces total harmonic distortion (THD), and improves overall system reliability. It is therefore well-suited for high-performance applications such as electric vehicle (EV) drives and renewable energy integration, where efficiency and waveform fidelity are critical.

Designing capacitors

The proper sizing of the switched capacitors is essential for the stable operation of the SCMLI. The design relies on the charge balance principle, which ensures that the capacitor can supply the required current without excessive voltage ripple during its conduction interval.

Capacitors C1 and C2 are typically charged over symmetrical conduction periods. The conduction angles are considered as:

-

C1: from θ3 to π − θ3,

-

C2: from θ4 to π − θ4.

The charge balance equation can be expressed as:

Assuming sinusoidal current:

The charge delivered during the conduction interval is:

Thus, the required capacitance is derived from:

This formulation ensures that during each conduction interval, the capacitor can provide the necessary energy without exceeding the allowable voltage ripple ΔV.

Similarly, the proposed topologies’ discharging periods are given as θ3 to π-θ3 and θ4 to π-θ4.

where Im stands for the peak output current, and VCx=1−4 stands for the switched capacitor ripple voltage.

This approach ensures that each capacitor can supply the required current during its designated conduction interval without exceeding the permissible voltage deviation. When connected in parallel with a DC power source, a capacitor naturally charges to the same voltage level as the source. Notably, supercapacitors exhibit nearly symmetrical charge and discharge characteristics across both the positive and negative half-cycles. This symmetrical behavior reduces the required capacitance value, thereby enhancing the system’s compactness and overall efficiency.

The evaluation of both charging current and capacitor voltage must account for the impact of parasitic elements and the specific discharge paths, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Under unity power factor conditions, the capacitor currents iC1 to iC4 can be accurately derived by considering these effects, ensuring reliable modeling of capacitor dynamics during operation.

The voltages across the capacitors during the charging intervals are derived from Eqs. (9) and (10). In these expressions, ESR denotes the equivalent series resistance of the capacitor, RD represents the resistance of the diodes, and Rds, on refers to the on-state resistance of the power switches. Additionally, VFD is the forward voltage drop across the diodes, while VDsw signifies the voltage drop across the switches in their conducting state. T represents the time constant of the charging circuit, defined as the product of the total resistance and capacitance in the path. The term iavgCx (for x = 1 to 4) corresponds to the average charging current through each capacitor branch.

Collectively, these parameters determine the transient behavior and voltage evolution of the capacitors during the charging process. Besides, this ensures that capacitors are sized correctly to maintain performance under varying load and modulation conditions.

Power loss analysis

The total power losses in the proposed SCMLI topology are divided into three major categories: conduction losses, switching losses, and ripple-related losses.

Conduction losses

Conduction losses occur as a result of the inherent resistive elements and voltage drops across semiconductor devices during current conduction. In the proposed inverter topology, these losses arise from both the capacitor charging current and the load current. Consequently, the total conduction losses can be categorized into two distinct components: (i) losses associated with the charging and discharging of flying capacitors, and (ii) losses due to the current delivered to the external load. This classification enables a more precise analysis of energy dissipation across different conduction paths within the inverter system.

In this topology, each switch is configured to conduct bidirectional current while blocking voltage in a single direction. Consequently, the total conduction loss associated with a switch must account for both the main switching element and its antiparallel diode. This combined loss can be accurately estimated using analytical models, such as those outlined in26, which consider key parameters including the switch’s on-state resistance, the forward voltage drop of the diode, and the temporal profile of current conduction throughout the switching cycle.

The parameters PCL, Sw and PCL, d represent the conduction losses associated with the main switch and its antiparallel diode, respectively, under the influence of the instantaneous current i(t). The terms VD, sw and VD, d denote the on-state voltage drops of the switch and the diode, while Rsw and Rd correspond to their respective on-state resistances. Additionally, the parameter β is a device-specific constant that characterizes the conduction behavior of the switch and is typically provided in the manufacturer’s datasheet.

Switching losses

The switching losses (PswL) have a significant impact on the overall efficiency of the inverter. These losses are calculated based on the blocking voltage (Vblock) of the switch, the average current flowing through it (iswavg), and the switching times, specifically the turn-on (tON) and turn-off (tOFF) durations. These parameters collectively determine the energy dissipated during each switching transition, as given in (13):

where fSw is the switching frequency of the inverter.

Ripple losses

Ripple losses (Prip, Loss) in the capacitors arise due to the mismatch between the charging voltage and the instantaneous capacitor voltage. During the charging process, energy is dissipated through various components in the charging path, including the ON-state resistance of the switches, the ESR of the capacitors, and the forward voltage drop of the diodes. These losses collectively contribute to the overall ripple loss. The ripple losses associated with the capacitors can be estimated using the method described in25.

where ΔVrip, i denotes the ripple voltage of capacitor Cx.

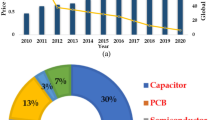

The power losses of individual components in the proposed topology were analyzed using PLECS simulation software. The detailed breakdown of these losses for a 350 VA load is presented in Fig. 4. It can be observed that most components exhibit relatively low power dissipation, except for those involved in the capacitor charging paths. This increase is primarily attributed to the presence of inrush currents during the charging process.

Results and discussion

Simulation results

In the simulation of the proposed nine-level quadratic boost switched-capacitor multilevel inverter (SCMLI), operating with an input voltage of 50 V, a load resistance of 50 Ω, and an inductance of 50 mH, several key behaviors are observed in the capacitor voltage and current waveforms. The switching frequency and the output fundamental frequency are set to 5 kHz and 50 Hz, respectively.

Figure 5 presents the detailed simulation results of the proposed SCMLI, demonstrating the inverter’s steady-state performance and component-level behavior. 5a shows the output voltage waveform (vo), which clearly exhibits nine discrete voltage levels, confirming the effectiveness of the modulation and switching strategy. The corresponding output current waveform (io) is illustrated in Fig. 5b, indicating a well-shaped sinusoidal profile with minimal distortion, validating the inverter’s capability to deliver high-quality current to the load. The voltage dynamics of the flying capacitors are depicted in Fig. 5c and d for vC1 and vC2, respectively, and in Fig. 5e and f for vC3 and vC4. Finally, the capacitor charging and discharging current waveforms are illustrated in Fig. 5g and h for iC1–iC2 and iC3–iC4, respectively. In addition, Fig. 6 shows the simulation results, output voltage, output current, capacitor currents C1, C2, C3, C4, and capacitor voltages C1, C2, C3, C4, of the proposed inverter under dynamic load changes.

With regard to voltage levels, capacitors C1 and C2 stabilize at approximately 50 V, closely matching the input voltage. These capacitors form part of the initial boosting stage and are directly charged from the input source. Their voltage levels are carefully regulated through controlled switching sequences to avoid overcharging and to maintain dynamic voltage balance within the system.

Conversely, capacitors C3 and C4 reach voltage levels around 100 V, reflecting their role in the secondary boosting stage. In a quadratic boost SC topology, energy transfer occurs in a staged manner, sequentially from the lower to the higher stage, effectively stacking the voltage levels to achieve the required multilevel output. The observed 100 V across C3 and C4 represents the cumulative voltage contribution of the first-stage capacitors, thereby enabling the generation of higher-level voltage steps needed for nine-level waveform synthesis. These voltage levels are critical to ensuring that the output waveform maintains equally spaced levels, which is essential for minimizing THD and enhancing output power quality.

Regarding current behavior, the charging currents through capacitors C1 to C4 (iC1–iC4) exhibit peak magnitudes of up to 7 A. These high currents are attributed to the inherent rapid charge–discharge dynamics of switched-capacitor circuits. When a capacitor is connected to a voltage source with a substantial voltage differential, a transient inrush current is generated due to the low-impedance path formed by the switch ON-resistance, the capacitor’s ESR, and the diode forward characteristics. Although these current spikes are brief, they can be considerable in magnitude, particularly in high-frequency switched-capacitor systems such as the proposed SCMLI.

While the 50 mH inductor placed on the load side influences the overall current response by smoothing the load current, it exerts limited damping on the instantaneous capacitor charging currents. However, the addition of a soft-charging inductor of 33 µH in the charging path helps to mitigate these current transients, reducing stress on switching components and enhancing system reliability. In addition, the proposed topology is simulated with a highly inductive load (R = 50 Ω, L = 500 mH) to demonstrate the capability of reactive power flow. The corresponding voltage and current waveforms are illustrated in Fig. 6(a)–(b), while the capacitor current and voltage characteristics are presented in Fig. 6(c)–(f). Since switch stress is a critical factor in inverter design, the blocking voltage (voltage stress) across the individual switches is analyzed and depicted in Fig. 7(a)–(i). It is observed that switches S4 and S4’ experience the maximum blocking voltage, which is equal to the peak output voltage (Vo, max). Similarly, the current stress on the switches is shown in Fig. 8(a)–(i). As discussed earlier, the highest current stress occurs in the switches involved in the capacitor charging path.

Experimental results

To verify the practical feasibility of the proposed nine-level SCMLI, a 350 W hardware prototype was developed and tested under various loading conditions. Figure 9 presents the complete laboratory test bench used in the experimental validation. As shown in the figure, the setup comprises key components including the SiC MOSFET power modules, DC source, gate driver circuits, and switched capacitors. The control unit is implemented using a TMS320F28379D dual-core DSP Launchpad, enabling precise timing control and high-speed switching operations. Measurement instruments such as voltage and current probes and a mixed signal oscilloscope (MSO) are used for capturing real-time waveforms. The load side includes configurable resistive and inductive elements (R and L load) to emulate different operating scenarios.

To ensure consistency between simulated and real-world conditions, both the simulation and experimental evaluation of the proposed nine-level SCMLI were conducted with a constant input voltage of 50 V. In both domains, switched capacitors C₁ and C₂ were charged to the input voltage (50 V), while C₃ and C₄ reached 100 V, collectively enabling a 200 V peak output voltage across the load terminals.

Due to practical constraints in the laboratory environment, the experimental setup required modifications in load selection compared to the idealized simulation conditions. While the simulation utilized lower load values to emphasize theoretical operation and waveform shaping, the hardware prototype employed higher resistive and reactive loads to align with equipment safety ratings and power limitations. Despite these adjustments, the experimental results exhibit excellent agreement with the simulation, thus confirming the viability and robustness of the proposed topology under realistic operating conditions.

A 350 W laboratory prototype was constructed to validate the inverter’s performance. The power stage is composed of SCT3080ALGC11 SiC MOSFETs, driven by HCPL-3140 optocoupler-based gate drivers, and supported by a 2.2 mF electrolytic capacitor for DC link voltage stabilization. Digital control is implemented on a Texas Instruments TMS320F28379D dual-core DSP Launchpad, which executes real-time switching sequences at a 5 kHz switching frequency. Experimental testing was conducted using a 100 V DC input under three loading scenarios: a purely resistive 100 Ω load, and two reactive loads: (50 + j100) Ω and (100 + j100) Ω, each representing distinct power factor conditions. This comprehensive evaluation provides insights into both steady-state behavior and the dynamic response of the inverter topology. The capacitors used in the prototype are specified as C₁ and C₂: 2.7 mF / 63 V (Model No. B41252C8278M000), C₃ and C₄: 3.3 mF / 200 V (Model No. B43630A2338M000).

Figure 9 presents a detailed view of the experimental test bench, highlighting the key hardware components, including the MOSFET power modules, DSP controller, switched capacitors, current and voltage probes, and the RL load bank. The waveform display from the MSO confirms correct voltage and current shaping.

In Fig. 10a, the output voltage and current waveforms under a purely resistive load are illustrated. The sinusoidal voltage and in-phase current indicate unity power factor operation, highlighting the system’s efficiency in resistive conditions. Furthermore, the voltage and current waveforms of capacitor C₁ are shown, demonstrating a peak voltage of approximately 50 V and a peak charging current of around 8 A, consistent with simulated predictions.

To manage high inrush currents during fast switching intervals, a soft-charging inductor (33 µH) was inserted between the input source and C₁. This inductor includes an anti-parallel diode to support freewheeling and ensure smoother capacitor charging, thereby enhancing device protection and extending component longevity.

To evaluate the inverter’s performance under inductive loading conditions, an impedance of 100 + j100 Ω, corresponding to a lagging power factor of approximately 0.95, was applied. The resulting output voltage and current waveforms, shown in Fig. 10b, confirm that the proposed topology maintains high waveform quality even under significant reactive power conditions. This demonstrates its suitability for grid-tied and motor drive applications where inductive loads are prevalent.

The dynamic response of the inverter was further tested by introducing a sudden load variation from 50 + j100 Ω to 100 + j100 Ω. As illustrated in Fig. 10c, the system exhibits a rapid and stable transition, with minimal overshoot and no visible distortion in the output voltage waveform. This indicates the robustness of both the power stage and the implemented control algorithm in handling abrupt changes in operating conditions.

To assess the inverter’s flexibility in output regulation, modulation index variation tests were performed. The modulation index was gradually reduced from 1 to 0.25 in discrete steps, and the corresponding output voltage levels are depicted in Fig. 10d–f. The results demonstrate the topology’s capability to dynamically adjust its output voltage according to reference commands or load demands, an essential feature for applications requiring real-time voltage control or energy-saving modes.

Lastly, the system’s response to input voltage variation was investigated. In Fig. 10g, the input voltage is changed from 40 V to 50 V, while Fig. 10h shows the resulting voltage waveforms of capacitors C₁, C₂, and C₃. The capacitor voltages remain well-regulated and balanced during the transition, validating the effectiveness of the capacitor voltage balancing mechanism and the inherent stability of the proposed inverter under fluctuating input conditions.

The efficiency of the proposed inverter topology is assessed as the ratio of output power to input power. The evaluation reveals a strong correlation between simulation and experimental results, confirming the accuracy and reliability of the developed model. A peak efficiency of 96.7% is achieved, indicating excellent energy conversion performance. Figure 11 presents a comparative analysis of efficiency versus output power under both simulated and experimental conditions. The close agreement between the two datasets highlights the robustness of the proposed topology across varying load scenarios. These findings underscore the inverter’s potential for deployment in renewable and hybrid energy systems, where high efficiency and resilience to input voltage fluctuations are critical design considerations.

The performance of inverter topologies is commonly assessed through comparative analysis with established designs. In this study, the proposed nine-level switched-capacitor topology is benchmarked against several existing multilevel inverter configurations, as summarized in Table 2. The comparison highlights that the proposed design offers superior performance across key parameters such as component count, voltage gain, output waveform quality, and overall efficiency. While the topology introduces a modest increase in voltage stress across the switches, this trade-off is considered acceptable given the significant improvements in power quality and circuit simplicity. These advantages affirm the proposed topology’s suitability for modern power conversion applications where compactness, efficiency, and waveform integrity are essential. Besides, the feasibility of the proposed topology under grid-connected operation is demonstrated in Fig. 12a, where the grid peak voltage is maintained at 325 V and the inverter output voltage is set to 400 V. Figure 12a illustrates the grid voltage and current waveforms, confirming operation at both unity and lagging power factors, thereby validating the capability of the proposed topology to function under different power factor conditions. Figure 12b presents the inverter output voltage waveform before filtering, while the complete simulation diagram of the grid-connected inverter system is shown in Fig. 12b. A conventional PQ controller is employed to regulate active and reactive power flow, ensuring unity power factor operation. The harmonic analysis of the proposed inverter under grid-connected operation is presented in Fig. 13a–d for both voltage and current. The voltage spectrum is evaluated before filtering, while the current FFT is measured at the point of common coupling (PCC). The results indicate that the voltage THD is 9.48%, whereas the current THD is maintained below 5%, which complies with the IEEE 519 standard and is suitable for distributed generation applications such as rooftop PV systems37,38.

Conclusions

This paper has introduced a novel SCMLI topology, supported by a comprehensive analysis of its operating principles, modulation strategy, and component design. The proposed configuration effectively combines voltage boosting and multilevel output generation without requiring magnetic components or complex control schemes. A detailed examination of the switching modes and capacitor voltage balancing has been carried out using mathematical modeling, while power loss mechanisms have been analyzed through PLECS-based simulations.

Simulation results reveal that the highest power losses occur in the capacitor charging path switches due to transient inrush currents. Despite this, the overall simulated efficiency reaches up to 97.2%, demonstrating the topology’s strong potential for high-efficiency applications. To validate the practicality of the proposed design, a 350 W hardware prototype was developed and tested under various loading scenarios, including both resistive and inductive conditions, as well as dynamic changes in input voltage and modulation index. The experimental results confirm a peak efficiency of 96.7%, closely matching the simulation outcomes.

These findings underscore the proposed inverter’s robust performance, high efficiency, and reliable operation under real-world conditions. Its ability to maintain stable output and capacitor voltage balance during abrupt transients makes it especially suitable for renewable energy integration, particularly in grid-tied photovoltaic (PV) and hybrid energy systems, where input variability and dynamic load conditions are common. Furthermore, integration with energy storage systems and adaptive MPPT (maximum power point tracking) controllers will be explored to broaden the applicability of the proposed design in smart grid and off-grid renewable energy environments.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Jagabar Sathik, M. & Vijayakumar, K. An assessment of recent multilevel inverter topologies with reduced power electronics components for renewable applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 82 (3), 3379–3399 (Feb. 2018).

Rodriguez, J., Lai, J. S. & Peng, F. Z. Multilevel inverters: A survey of topologies, controls, and applications, IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 724–738, Aug. (2002).

Araujo, S. V., Zacharias, P. & Mallwitz, R. Highly efficient single-phase transformerless inverters for grid-connected photovoltaic systems, IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol. 57, no. 9, pp. 3118–3128, Sep. (2010).

Naik, B. S., Suresh, Y., Aditya, K. & Rao, B. N. A novel nine-level boost inverter with a low component count for electric vehicle applications. Int. Trans. Electr. Energ. Syst. 31 (12), e13172. https://doi.org/10.1002/2050-7038.13172 (2021).

Naik, B. S., Suresh, Y., Venkataramanaiah, J. & Panda, A. K. Nine-Level inverter topology with boosting capability and reduced component count. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs. 68 (1), 316–320. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2020.2998496 (Jan. 2021).

Sathik, M. J., Tang, Z., Yang, Y., Vijayakumar, K. & Blaabjerg, F. A New 5-Level ANPC Switched Capacitor Inverter Topology for Photovoltaic Applications, IECON 2019–45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Lisbon, Portugal, pp. 3487–3492, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/IECON.2019.8926832

Barzegarkhoo, R., Moradzadeh, M., Zamiri, E., Madadi Kojabadi, H. & Blaabjerg, F. A New Boost Switched-Capacitor Multilevel Converter With Reduced Circuit Devices, in IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, vol. 33, no. 8, pp. 6738–6754, Aug. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2017.2751419

Mohamed Ali, J. S. & Krishnasamy, V. Compact switched capacitor multilevel inverter (CSCMLI) with Self-Voltage balancing and boosting ability. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 34 (5), 4009–4013. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2018.2871378 (May 2019).

Ye, Y., Cheng, K. W. E., Liu, J. & Ding, K. ‘‘A step-up switched capacitor multilevel inverter with self-voltage balancing,’’ IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol. 61, no. 12, pp. 6672–6680, Dec. (2014).

Zamiri, N., Vosoughi, S. H., Hosseini, R., Barzegarkhoo & Sabahi, M. ‘A new cascaded switched-capacitor multilevel inverter based on improved series–parallel conversion with less number of components’. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 63 (6), 3582–3594 (Jun. 2016).

Fong, Y. C., Ye, Y., Raman, S. R., Cheng, K. W. E. & Exposition IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and A hybrid multilevel inverter employing series-parallel switched-capacitor unit, (APEC), Tampa, FL, USA, 2017, pp. 2565–2570, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/APEC.2017.7931059

Sathik, M. J., Sandeep, N., Siddique, M. D., Almakhles, D. & Mekhilef, S. Compact Seven-Level Boost Type Inverter Topology, in IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs, vol. 68, no. 4, pp. 1358–1362, April (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2020.3039387

Barzegarkhoo, R., Kojabadi, H. M., Zamiry, E., Vosoughi, N. & Chang, L. ‘Generalized structure for a single phase switched-capacitor multilevel inverter using a new multiple DC link producer with reduced number of switches’. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 31 (8), 5604–5617 (Aug. 2016).

Fallah Talooki, M., Rezanejad, M., Khosravi, R. & Samadaei, E. ‘‘A novel high step-up switched-capacitor multilevel inverter with self-voltage balancing,’’ IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 4352–4359, Apr. (2021).

Liu, J., Wu, J. & Zeng, J. ‘‘Symmetric/Asymmetric hybrid multilevel inverters integrating switched-capacitor techniques, IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Power Electron., vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 1616–1626, Sep. (2018).

Sandeep, N., Ali, J. S. M., Yaragatti, U. R. & Vijayakumar, K. ‘‘A self balancing five-level boosting inverter with reduced components,’’ IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 34, no. 7, pp. 6020–6024, Jul. (2019).

Surapu, P. R., Sandeep, N. & Verma, A. K. ‘‘A nine-level midpoint clamped inverter with full DC-bus utilization and suppressed charging current for PV application,’’ IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Power Electron., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 2972–2980, Jun. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/JESTPE.2024.3375391

Sekar, R., Jagabar Sathik, M., Alghaythi, M. L., Alshammari, M. S. & Vijayakumar, K. Lower energy Storage-Based 9L- switched capacitor ANPC inverter topology with voltage boosting Features, in IEEE access, 13, pp. 25958–25968, (2025). https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3535941

Sathik, M. J. & Nine Level, A. ANPC Boost Type Inverter Topology With Reduced Component Stress, in IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs, vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 380–384, Jan. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2023.3305230

Kumari, M., Siddique, M. D., Sarwar, A., Mekhilef, S. & Tariq, M. ‘‘A twice boost nine-level switched-capacitor multilevel (2B-9L-SCMLI) inverter with self-voltage balancing capability,’’ Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl., vol. 49, no. 8, pp. 2578–2592, Aug. (2021).

Mohamed Ali, J. S. et al. ‘‘Experimental validation of nine-level switched-capacitor inverter topology with high voltage gain,’’ Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl., vol. 49, no. 8, pp. 2479–2493, Aug. (2021).

Dhasharatha et al. A novel Nine-Level quadruple boost inverter for electric vehicle applications. IEEE Access. 12, 60694–60704 (2024).

Kumar, R., Raushan & Chakraborty, S. A single source quadruple boost Nine-Level Switched-Capacitor inverter with reduced components and continuous input current. IEEE Access. 12, 52922–52933 (2024).

Pal, P. K., Jana, K. C., Siwakoti, Y. P., Majumdar, S. & Blaabjerg, F. ‘‘An active-neutral-point-clamped switched-capacitor multilevel inverter with quasi-resonant capacitor charging,’’ IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 37, no. 12, pp. 14888–14901, Dec. (2022).

Liu, J., Lin, W., Wu, J. & Zeng, J. ‘A novel nine-level quadruple boost inverter with inductive-load ability’. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 34 (5), 4014–4018 (May 2019).

Iqbal, M. D., Siddique, B. P., Reddy & Maroti, P. K. ‘‘Quadruple boost multilevel inverter (QB-MLI) topology with reduced switch count,’’ IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 36, no. 7, pp. 7372–7377, Jul. (2021).

Jena, K., Panigrahi, C. K., Gupta, K. K. & Kumar, D. A generalized transformerless switched-capacitor inverter for photovoltaic application. Electr. Eng. 104 (5), 3435–3444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-022-01496-6 (2022).

Jena, K., Panigrahi, C. K., Gupta, K. K., Kumar, D. & Dewangan, N. K. Generalized switched-capacitor multilevel inverter topology with self-balancing capacitors. J. Power Electron. 22 (9), 1617–1626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43236-022-00456-4 (2022).

Jena, K. et al. A single DC source generalized switched capacitors multilevel inverter with minimal component count. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2023, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/3945160 (2023).

Jena, K., Gupta, K. K. & Kumar, D. A 4-X gain 9-Level multilevel inverter topology with reduced part count. Sci. Iran. 0 (0), 0–0. https://doi.org/10.24200/sci.2025.65182.9341 (2025).

Tayyab, M., Sarwar, A., Bakhsh, F. I., Al-Durra, A. & Siddiqui, K. M. A single-source nine-level inverter with quadratic boost ability for renewable energy applications. IET Renew. Power Gener. 19 (1). https://doi.org/10.1049/rpg2.12549 (2025).

Sandeep, N. & Ali, J. S. An Improved Quadruple-Boost Switched-Capacitor-Based Nine-Level Inverter, IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 38, no. 8, pp. 9335–9339, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2023.3272915

Alaas, Z. A new active neutral point clamped (ANPC) nine-level inverter topology with low energy storage switched capacitors. Sci. Rep. 15 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87302-2 (2025).

Ali, D. & Doss, M. A. N. High-efficiency nine-level inverter using switched-capacitor technique with optimized switch count. Electr. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-025-03211-7 (2025).

Saeedian, M., Adabi, M. E., Hosseini, S. M., Adabi, J. & Pouresmaeil, E. A novel step-up single source multilevel inverter: Topology, operating principle, and modulation, IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 3269–3282, Apr. (2019).

Sathik, M. J., Sandeep, N., Almakhles, D. J. & Yaragatti, U. R. A Five-Level Boosting Inverter for PV Application, in IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 5016–5025, Aug. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/JESTPE.2020.3046786

Rawa, M. et al. Optimal Allocation and Economic Analysis of Battery Energy Storage Systems: Self-Consumption Rate and Hosting Capacity Enhancement for Microgrids with High Renewable Penetration. Sustainability (2071 – 1050). ;12(23). (2020).

Aleem, H. E. A., Shady, M. T., Elmathana, Ahmed, F. & Zobaa Different design approaches of shunt passive harmonic filters based on IEEE Std. 519–1992 and IEEE Std. 18-2002. Recent Patents on Electrical & Electronic Engineering (Formerly Recent Patents on Electrical Engineering) 6, no. 1 : 68–75. (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author, ZA, takes full responsibility for every aspect of this research. This includes the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, as well as drafting, revising, and giving final approval to the manuscript. ZA has ensured the accuracy and integrity of all components of the work and has approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alaas, Z. High-gain boost-type switched capacitor nine-level inverter topology with reduced device count. Sci Rep 15, 40263 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24137-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24137-x