Abstract

Additive Manufacturing (AM) processes are new ways of producing techniques that work by printing parts layer upon layer using 3D models. AM has some subcategories, which are classified according to the used parent materials. Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) is a material-extrusion-based technique and is mostly used for rapid prototyping and in some cases for a real servicing part. In the FDM technique, input parent materials are commercial polymers and also, it has some important manufacturing parameters including raster and layer configurations, infill density, layer height, nozzle and bed temperatures, nozzle diameter, and printing speed. Among the mentioned parameters, the infill pattern has a significant effect on the mechanical performance of the FDM products. Thus, the current paper surveyed the effect of five different infill patterns (Grid, Triangle, Wiggle, Fast honeycomb, and Full honeycomb) on the tensile and bending strength of the FDM-Polylactic Acid (FDM-PLA) specimens. Each bending specimen has 50 layers, 10 layers from top and bottom considered solid state, and 30 middle layers printed with the mentioned infill patterns. The results revealed that the specimens that were printed with a Wiggle infill pattern showed the highest values of mechanical properties. For instance, the ultimate tensile strength of the Wiggle and Full honeycomb infill patterns were 43.11 MPa and 28.33 MPa, respectively. However, the Triangle infill pattern presented the highest bending strength (failure load was 9,341 N) and the lowest failure strength was related to the specimens printed with a Full honeycomb infill pattern (failure load was 6,394 N). The obtained results in this paper are comprehensively discussed in the results and discussion section.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

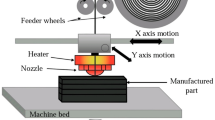

In Additive Manufacturing (AM) techniques, devices are directed to deposit material in precise geometric shapes layer by layer using computer-aided design (CAD) software or 3D object scanners. Additive manufacturing creates objects by adding material, as the name suggests1. In contrast, material removal through milling, machining, carving, shaping, or other methods is frequently required when creating an object using traditional methods2. Recently, many industries such as automobile, aerospace, medicine, food, etc. used the AM processes to produce some parts3. It should be noted that AM is classified into various technologies according to the used source energy or used initial parent material4. Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) is a subcategory of AM processes and is known as an extrusion-based one5. For this manufacturing process, the initial parent materials are the commercial polymers including Polylactic Acid (PLA)6, Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS)7, Polycarbonate (PC)8, Wood, Poly Ether Ketone (PEEK)9. Among the mentioned input materials, the PLA are widely used for its intrinsic properties and two important industry namely medical and food industries are implementing this polymer for fabricating many parts and instruments10. Some manufacturing parameters are involved in the FDM technique and these parameters have a direct influence on the final quality and mechanical properties of a sample printed through this process. In-plane raster angle11, build direction12, nozzle diameter13, nozzle and bed temperature14, infill density15, infill pattern, layer thickness15, and printing speed16 are the main manufacturing parameters in the FDM technique. However, assuming various values for these parameters depends on the parent material catalog and the 3D printer operator. Many applications are revealed for FDM parts and recently, Qin et al.17 used FDM technique for printing Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) for stress measurement in soil mass. Recent advancements in additive manufacturing have demonstrated significant improvements in process efficiency and material utilization, as highlighted by Li et al.18. For instance, Chen et al.19 investigated various aspects in digital light processing to figure out their influences on mechanical performance. As stated earlier, the mechanical performance of the FDM samples can vary with the manufacturing parameters, thus, nowadays, some researchers are trying to find out how the mentioned manufacturing parameters can affect the mechanical properties of the FDM samples. Here, some research studies that have been done on the effects of these manufacturing parameters on the mechanical integrity of the FDM samples are briefly described.

One of the manufacturing parameters is the layer thickness where the higher values of them result in speeding up the printing process and lower the final price of the part fabricated by the FDM. With this in mind, Pritish Shubham et al.20 printed tensile samples with different layer thicknesses of 0.075, 0.10, and 0.25 mm from the ABS material. The tensile results confirmed that as the mentioned parameter increased the ultimate tensile strength decreased. The impact of feed rate, layer thickness, and build direction on the tensile and bending characteristics of the FDM-PLA samples were examined by Chacon et al.21. In comparison to the on-edge and flat orientations, the upright orientation demonstrated the lowest mechanical performance, according to the results. Furthermore, it was noted that the printed samples’ ductility reduced with increasing layer thickness and feed rate. The FDM process, as previously indicated, creates a part layer by layer, which makes the slicing program a crucial task. As a result, Ozen et al.22 selected the slicer parameter as a manufacturing parameter and looked into how it affected the FDM-PETG samples’ tensile characteristics. For the purpose of creating the tensile samples, they employed two distinct slicing techniques in addition to introducing a new one. The researchers who obtained the results indicated that the new approach detected a more homogenous structure and that travel lines were shortened. Additionally, the printed tensile samples had improved bonding strength as a result of the new slicing technique. Because different raster angles resulted in different amounts of energy being absorbed by the 3D-printed specimen, it was reported that the tensile strength of FDM parts was highly dependent on the raster orientation23. However, by changing the build direction and raster orientation, researchers found that the thermal characteristics of the manufactured FDM parts also varied significantly24. The FDM-ABS tensile specimens’ critical build direction was determined by Gorski et al.25. The fabricated sample fractured in a brittle manner when the angle between the load direction and layer plane was greater than 25o, but the sample displayed plastic deformation if the angle was less than that critical value. Additionally, Bardiya et al.26 found that FDM-PLA specimens with a 30o layer orientation and an 80% infill density had the highest flexural strength. It should be noted that in recent years, different researchers tried to figure out the mechanical characteristics of various structures through use of machine learning. For instance, Huang et al.27 worked on this issue and some information can be found. Also, deep learning as one of the most effective machine learning techniques are mostly used in various fields of predicting even in concrete and tall structures28.

Based on the literature review, new infill patterns should be considered to see how the internal elements and structures can absorb the exerted energy induced by the external loading conditions. Hence, five infill patterns were used to print the test samples and comprehensive discussions were reported on energy absorption process.

Experimental procedure

Material

As stated earlier in the previous section, the FDM technique uses commercial polymers including PLA, ABS, PC, etc. as initial parent material in the shape of filament (i.e., wire form). In the current research paper, PLA filament with an initial diameter of 1.75 mm was used as an input material for the FDM machine. PLA can be found in various colors29 and white color was selected here and renewable resources like corn starch or sugar cane are the source of recyclable, natural thermoplastic polyester known as PLA filament30. The physical and mechanical properties of this material are reported in Table 1.

Printing process

In the FDM technique, some manufacturing parameters should be assumed or checked to print the samples with high mechanical integrity32. Selection of these parameters relies on the parent material catalog (here it was PLA filament) or machine operator33. However, here, nozzle diameter, nozzle temperature, bed temperature, layer orientation, printing speed, infill density, and layer thickness were set at 0.4 mm, 220 °C, 60 °C, flat (i.e., samples were laid on the printer bed), 55 mm/s, 100%, and 0.2 mm, respectively.

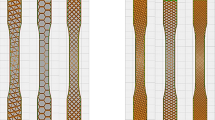

It should be noted that the main purpose of this research study was to understand how different infill patterns could control the tensile mechanical properties and bend strength of the FDM-PLA samples. Thus, in both tensile and bending samples, middle layers were printed considering various infill patterns of Grid, Triangle, Wiggle, Fast Honeycomb, and Full Honeycomb. More detailed information about these patterns is clarified in the next section.

Test samples

First, tensile samples (i.e., dog-bone-shaped) were selected, designed, and printed according to the ASTM-D638 standard (samples named type IV)34. A real printed tensile sample together with dimensions is illustrated in Fig. 1. According to the printing parameters stated in Sect. 2.2, each layer was printed with 0.2 mm thickness, thus, each tensile sample consisted of 30 layers. It should be noted that five layers from the bottom and top of the tensile samples were printed in completely solid form and the middle layers were printed with five different configurations of Grid, Triangle, Wiggle, Fast Honeycomb, and Full Honeycomb.

To investigate the bending strength of the FDM-PLA samples that were printed with different infill patterns, rectangular-shaped samples with 60 × 30 × 10 mm dimensions were printed through the use of the FDM technique. As mentioned above, each layer had 0.2 mm thickness, thus, each bending sample consisted of 50 layers. Also, 30 middle layers were printed with the infill patterns of Grid, Triangle, Wiggle, Fast Honeycomb, and Full Honeycomb. Then, 10 layers from top and bottom were printed in solid form.

It should be noted that all the tensile and bending samples were named Gr, Tr, Wi, Fa, and Fu as representative of infill patterns of Grid, Wiggle, Fast Honeycomb, and Full Honeycomb, respectively.

Figure 2 shows the rectangular-shaped sample that was printed for the bending experiments together with the various infill patterns.

Experiments

As it is clear, the first object in each research study in the field of mechanical properties is to evaluate the tensile mechanical properties. Hence, a universal testing machine was implemented to test the printed dog-bones. To extract the stress-strain curves, first, the loads were recorded by the load cell, and then, stresses were calculated by dividing the obtained loads into cross-section area (which 60 mm2 in the current research). The second issue was related to obtain the strain values and to get these values with high precision, the Digital Image Correlation (DIC) technique was implemented. In this technique, a spackle pattern35 with black dots was prepared on the dog-bone surfaces (see Fig. 3) and a camera with high degrees of resolution was used to capture the photos during the tensile experiments with 5s time intervals. The main concept of this was to trace the dots on the surface of the samples in order to calculate the displacements and then, the strain by considering the initial reference length36. All the tensile tests were done with a 2 mm/min displacement control rate and to ensure the repeatability of the tensile experiment, each test was repeated three times. After collecting the captured images, all of them were imported to the GOM-Correlate software37 to evaluate the strain in the vertical and horizontal directions. The tensile test machine and DIC setup are exhibited in Fig. 4.

Bending tests were also conducted with a 2 mm/min displacement control rate in a three-point bending test setup. Each bending test was repeated three times to ensure the repeatability of the experiments38. It is worth noting that the three-point test setup consisted of three rollers where the upper one transferred the external load to the rectangular-shaped samples and the other two rollers were completely fixed in the bottom of the bent samples. Figure 5 demonstrates this setup and the rectangular-shaped sample under the compressive loading condition.

Results and discussions

The main purpose of the current research paper was to investigate the effects of different infill patterns on the mechanical performance and bending strength of the FDM-PLA samples. After conducting the experiments as explained in the previous sections, the obtained results are presented in this section and comprehensive discussions about the results are stated below.

Tensile results

The representative stress-strain curves of the FDM-PLA samples that experienced tensile loading conditions are shown in Fig. 6. Besides, the summary of the tensile properties is reported in Table 2. In this table, E, υ, σU, σY, and εFailure denote the elastic modulus (i.e., Young’s modulus), Poisson’s ratio, ultimate tensile strength, yield strength, and strain at failure point, respectively. As it is obvious in Fig. 6; Table 2, the highest value of the ultimate tensile strength was related to the samples that were printed with a Wiggle (named Wi) infill pattern. The Triangle infill pattern was in the second position after the Wiggle one from the ultimate tensile strength point of view. Full and Fast honeycomb (i.e., Fa and Fu samples) infill patterns resulted in similar mechanical properties because fast and full honeycomb patterns only had a difference in number of the honeycombs inside the sample. Thus, load-carrying capacity of these patterns had a similar load distribution mechanism.

As a matter of fact, parts that are printed through the FDM technique have elastic-plastic behavior due to the intrinsic nature of the polymeric filaments. Here, the plastic deformation of the tensile samples was completely obvious, and the tensile sample with a Wiggle infill pattern showed the highest elongation and strain at the failure point. Three infill patterns of Grid, Fast honeycomb, and Full honeycomb (i.e., samples named Gr, Fa, and Fu) resulted in somewhat similar results from a plastic deformation point of view. There was an exception about the Triangle infill pattern and this pattern led to lower amounts of elongation at failure.

For exploring the reasons behind the obtained results in Fig. 6; Table 2; Fig. 2 should be considered carefully. Wiggle infill pattern mostly liked to zig-zag pattern, thus, when a tensile sample experienced the external load, these zig-zag patterns should be stretched and changed into a straight line. Then, the straight lines carried the external tensile load and the whole sample failure. In the Triangle infill pattern, a similar mechanism that was mentioned for the Wiggle one happened. The lower mechanical properties of the two honeycomb patterns were due to the shape of the honeycombs inside the tensile sample. The shape of these patterns (i.e., Fa and Fu samples) resulted in the creation of stress concentration zones inside the sample and earlier failure occurred. Thus, for minimizing the stress concentration inside the samples that were printed with two infill patterns of Fast and Full honeycomb patterns, some other techniques might be useful such as shot-pining and heat treatments or any other post-processes.

Grid infill pattern inside the tensile samples resulted in the average mechanical properties among the other ones and this infill pattern is mostly used pattern for printing the FDM part.

However, the results examined in the current research study can be useful for designers and 3D printing systems to print the products with the Wiggle infill pattern because this pattern could present superior performance from all of the mechanical properties points of view.

In some cases, in industrial projects, the weight of the parts is a critical issue. To this end, the weight of the tensile FDM-PLA samples was measured before the experiments and reported in Table 3. Also, after performing the tensile experiments, the strength-to-weight ratios of the samples that were printed with different infill patterns were evaluated (see last column of Table 3). This parameter shows that a sample with a specific weight acts under different loading conditions. The highest value of strength-to-weight ratio belonged to the tensile samples printed with the Wiggle infill pattern.

Bending strength results

The rectangular-shaped samples were loaded in the three-point bending setup and load-displacement curves were recorded and plotted as seen in Fig. 7. The summary of the failure loads obtained from the three-point compressive experiments is reported in Table 4. Based on Fig. 7, all the load-displacement curves had a nonlinear behavior, thus, plastic deformation in the printed samples with various infill patterns was completely obvious. Comparing the plastic behavior with the brittle one presents that the materials and parts with plastic behavior can absorb more amounts of exerted energies, therefore, for some structures that are exposed to the loads, plastic behavior can be useful. With this in mind, the samples that were printed with some manufacturing parameters in the current research paper can be good choices for use in various industries.

According to Fig. 7; Table 4, rectangular specimens fabricated with the Triangle infill pattern exhibited superior average failure loads compared to other configurations. These specimens contained numerous microscopic triangular elements within their internal structure, with each triangle functioning as a truss member. Consequently, when external loads were applied to these specimens, two truss members shared the load distribution, resulting in enhanced failure load capacity. In addition to improved failure load characteristics, specimens printed with the Triangle infill pattern (designated as Tr) demonstrated the highest elongation values, indicating superior energy absorption capability compared to alternative infill patterns. Following the Triangle infill pattern, the Wiggle configuration achieved the second-highest failure load performance. This significant finding contrasts with the tensile test results. As previously discussed, the Wiggle infill pattern exhibits a zigzag geometry (illustrated in Fig. 2), and under tensile loading conditions, these patterns can extend and subsequently transform into straightened elements, thereby increasing failure load capacity. However, when zigzag patterns are subjected to compressive loading, the rasters within this configuration demonstrate reduced load-bearing capacity. It is important to note that the primary mechanism governing the observed mechanical properties and bending strength relates to the orientation of internal structural elements within the Tr and Wi specimens. The underlying phenomenon may be attributed to the deformation characteristics of the distinctive elements comprising the Tr and Wi patterns.

The lowest value of the failure load was related to the printed rectangular-shaped sample with the Full honeycomb (i.e., Fu samples) infill pattern. Again, this issue might arise from the stress concentration zones in the intersection points. But vise-versa result was ween for the samples that were printed with Fast honeycomb (i.e., Fa samples) infill patterns. However, the presence of the stress concentration zones in these samples was undeniable but in this infill pattern, tiny honeycombs could reduce the stresses. Also, the area of a single honeycomb was an important factor and the fast honeycomb infill pattern had less area in comparison to the full honeycomb infill pattern. Therefore, when the sample started to collapse during the compressive experiment, the honeycomb in the fast infill pattern collapsed earlier and high amounts of collapsed areas resulted in a higher bending strength compared to the full honeycomb infill pattern.

Other infill patterns presented similar results from a failure load point of view. The most important aspect of this paper was to understand how two infill patterns of Wiggle and Triangle could improve the mechanical performance and bending strength of the FDM-PLA samples.

Here, again, the strength-to-weight ratios were measured like the previous section. After measuring the rectangular-shaped samples that were printed with various infill patterns, the failure loads were considered and the ratio of strength-to-weight was evaluated and summarized in Table 5.

As seen in Table 5, the highest ratio of the strength-to-weight belonged to the samples that were printed with the Triangle infill pattern. The discrepancy between the highest and lowest (which was related to the Grid infill pattern) strength-to-weight ratio was about 39%.

However, most of the research studies used the Grid infill pattern to print their samples and according to the obtained results in the current paper, this infill pattern presented weak performance compared to the other infill patterns.

To understand how these patterns can affect the mechanical performance of the FDM parts intrinsically, some finite element analyses may be needed to observe how the pattern such as a honeycomb or triangle deforms under the external loads.

Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the influence of five different infill patterns of Grid, Triangle, Wiggle, Fast honeycomb, and Full honeycomb on the tensile properties and bending strength of the samples that were printed through the use of the Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) technique. Because of some important properties of Polylactic Acid material, this material was chosen as the input parent material. However, the results drawn from this paper are summarized below:

-

The Wiggle infill pattern resulted in higher mechanical properties due to the zig-zag-shaped infill pattern. When a sample was printed with the Wiggle infill pattern, first, the zig-zags were stretched out and changed into straight lines. Thus, more exerted energies could be dissipated.

-

Fast and Full honeycomb infill patterns resulted in lower mechanical properties compared to the Grid and Triangle infill patterns. The reason behind this issue was related to the creation of stress concentration zones.

-

Rectangular-shaped samples that were printed with the Triangle infill pattern presented the highest amounts of failure loads. Each sample with the Triangle infill pattern consists of many tiny triangles which act as trusses. Thus, more compressive loads could be absorbed by these samples.

-

The primary mechanism governing the observed mechanical properties and bending strength relates to the orientation of internal structural elements within the Tr and Wi specimens.

Future studies can be related to the finite element modeling the studies infill patterns to see how stresses and strains are distributed along the pattern and how the stress concentration zones and weak spots are created.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Frazier, W. E. Metal additive manufacturing: a review. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 23, 1917–1928 (2014).

Van Sice, C. & Faludi, J. Comparing environmental impacts of metal additive manufacturing to conventional manufacturing. Proc. Des. Soc. 1, 671–680 (2021).

Javaid, M., Haleem, A., Singh, R. P., Suman, R. & Rab, S. Role of additive manufacturing applications towards environmental sustainability. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 4, 312–322 (2021).

Gibson, I. et al. Additive Manufacturing Technologies Vol. 17 (Springer, 2021).

Chennakesava, P. & Narayan, Y. S. Fused deposition modeling-insights. Proc. Int. Conf. Adv. Des. Manuf. ICAD&M. 14, 1345 (2014).

Drummer, D., Cifuentes-Cuéllar, S. & Rietzel, D. Suitability of PLA/TCP for fused deposition modeling. Rapid Prototyp. J. 18, 500–507 (2012).

Ahn, S. H., Montero, M., Odell, D., Roundy, S. & Wright, P. K. Anisotropic material properties of fused deposition modeling ABS. 8. (2002). https://doi.org/10.1108/13552540210441166

Zhou, Y., Zou, J., Wu, H. & Xu, B. Balance between bonding and deposition during fused deposition modeling of polycarbonate and acrylonitrile-butadiene‐styrene composites. Polym. Compos. 41, 60–72 (2020).

Wang, P., Zou, B., Xiao, H., Ding, S. & Huang, C. Effects of printing parameters of fused deposition modeling on mechanical properties, surface quality, and microstructure of PEEK. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 271, 62–74 (2019).

Lebedev, S. M. et al. Mechanical properties of PLA-based composites for fused deposition modeling technology. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 97, 511–518 (2018).

Huang, B. & Singamneni, S. Raster angle mechanics in fused deposition modelling. J. Compos. Mater. 49, 363–383 (2015).

Mohamed, O. A., Masood, S. H. & Bhowmik, J. L. Optimization of fused deposition modeling process parameters: a review of current research and future prospects. Adv. Manuf. 3, 42–53 (2015).

Vicente, C. M. S., Martins, T. S., Leite, M., Ribeiro, A. & Reis, L. Influence of fused deposition modeling parameters on the mechanical properties of ABS parts. Polym. Adv. Technol. 31, 501–507 (2020).

Zhou, Y., Nyberg, T., Xiong, G. & Liu, D. Temperature analysis in the fused deposition modeling process. 3rd Int. Conf. Inf. Sci. Control Eng., IEEE. 2016, pp. 678–82. (2016).

Dave, H. K., Patadiya, N. H., Prajapati, A. R. & Rajpurohit, S. R. Effect of infill pattern and infill density at varying part orientation on tensile properties of fused deposition modeling-printed poly-lactic acid part. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 235, 1811–1827 (2021).

Ansari, A. A. & Kamil, M. Effect of print speed and extrusion temperature on properties of 3D printed PLA using fused deposition modeling process. Mater. Today Proc. 45, 5462–5468 (2021).

Qin, Y., Wang, Q., Xu, D., Yan, J. & Zhang, S. A fiber Bragg grating based Earth and water pressures transducer with three-dimensional fused deposition modeling for soil mass. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 14, 663–669 (2022).

Li, R. et al. Application of unsupervised learning methods based on video data for real-time anomaly detection in wire Arc additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 143, 37–55 (2025).

Chen, S., Khan, S. B., Li, N. & Xiao, C. In-depth analysis of sintering, exposure time, and layer height (um) in LRS 3D printed devices with DLP. J. Manuf. Process. 133, 576–591 (2025).

Shubham, P., Sikidar, A. & Chand, T. The influence of layer thickness on mechanical properties of the 3D printed ABS polymer by fused deposition modeling. Key Eng. Mater. 706, 63–67 (2016).

Chacón, J. M., Caminero, M. A., García-Plaza, E. & Núnez, P. J. Additive manufacturing of PLA structures using fused deposition modelling: effect of process parameters on mechanical properties and their optimal selection. Mater. Des. 124, 143–157 (2017).

Özen, A., Auhl, D., Völlmecke, C., Kiendl, J. & Abali, B. E. Optimization of manufacturing parameters and tensile specimen geometry for fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D-printed PETG. Mater. (Basel). 14, 2556 (2021).

Oviedo, A. M., Puente, A. H., Bernal, C. & Pérez, E. Mechanical evaluation of polymeric filaments and their corresponding 3D printed samples. Polym. Test. 88, 106561 (2020).

Sonsalla, T., Moore, A. L., Radadia, A. D. & Weiss, L. Printer orientation effects and performance of novel 3-D printable acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) composite filaments for thermal enhancement. Polym. Test. 80, 106125 (2019).

Górski, F., Wichniarek, R., Kuczko, W. & Andrzejewski, J. Experimental determination of critical orientation of ABS parts manufactured using fused deposition modelling technology. J. Mach. Eng. 15, 121–132 (2015).

Bardiya, S., Jerald, J. & Satheeshkumar, V. The impact of process parameters on the tensile strength, flexural strength and the manufacturing time of fused filament fabricated (FFF) parts. Mater. Today Proc. 39, 1362–1366 (2021).

Huang, G., Zhang, L., Chu, S., Xie, Y. & Chen, Y. A highly ductile carbon material made of triangle rings: A study of machine learning. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124 (4),https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0189906 (2024).

Long, X., Li, H., Iyela, P. M. & Kang, S-B. Predicting the bond stress–slip behavior of steel reinforcement in concrete under static and dynamic loadings by finite element, deep learning and analytical methods. Eng. Fail. Anal. 161, 108312 (2024).

Hanon, M. M., Zsidai, L. & Ma, Q. Accuracy investigation of 3D printed PLA with various process parameters and different colors. Mater. Today Proc. 42, 3089–3096 (2021).

Liu, W., Zhou, J., Ma, Y., Wang, J. & Xu, J. Fabrication of PLA filaments and its printable performance. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., vol. 275, IOP Publishing; p. 12033. (2017).

www.matweb.com/PLA filament n.d.

Ferretti, P. et al. Relationship between FDM 3D printing parameters study: parameter optimization for lower defects. Polym. (Basel). 13, 2190 (2021).

Song, R. & Telenko, C. Material and energy loss due to human and machine error in commercial FDM printers. J. Clean. Prod. 148, 895–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.171 (2017).

ASTM D638. Test method for tensile properties of plastics. ASTM Int. 15(2014).

Patel, S. & Martin, C. D. Evaluation of tensile young’s modulus and poisson’s ratio of a bi-modular rock from the displacement measurements in a Brazilian test. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 51, 361–373 (2018).

McCormick, N. & Lord, J. Digital image correlation. Mater. Today. 13, 52–54 (2010).

Correlate, G. O. M. GOM Correlate. GOM GmbH Schmitzstraße. 2, 38122 (2018).

Shah, V. Handbook of Plastics Testing and Failure Analysis (Wiley, 2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

authors wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Luo, L., Wang, L. et al. Bending strength measurement of structures printed via fused deposition modeling with different infill patterns. Sci Rep 15, 40282 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24148-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24148-8