Abstract

Phenol contamination in water poses serious risks to human health and ecosystems, necessitating low-cost and sustainable treatment options. This study investigates the preparation of biochar from Vicia Faba Stems (VFS) through direct pyrolysis at 600 °C and evaluates its efficiency in phenol removal from aqueous solutions. The produced VFS biochar (VFSB) was characterized using Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis for surface area, Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy for functional groups, X-ray Diffraction (XRD) for structural features, and pHPZC for surface charge. VFSB exhibited a high carbon content (83.1%), porous sheetlike structure, and surface area of 144.34 m²/g, with a pHPZC of 6. Batch adsorption experiments showed rapid equilibrium within 3 h and a maximum removal efficiency of 88.86% at pH 6. The adsorption capacity increased by 45.82% across pH 2–12, with an average uptake of 19.30 ± 3.61 mg/g. Adsorption followed pseudo-second-order kinetics, while equilibrium data fit the Freundlich isotherm, indicating multilayer adsorption. Thermodynamic analysis revealed the process is spontaneous and endothermic. Reusability tests confirmed four adsorption cycles, with efficiency decreasing from 88.86% to 47.31%. The findings establish Vicia faba stem biochar as effective for phenol removal and highlight its potential to guide future studies on affordable, reusable, and practical solutions for organic contaminant treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The widespread presence of synthetic compounds and emerging contaminants has become a major environmental issue due to their persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and adverse effects on human and ecological health. Many of these substances pose long-term risks to biological systems through their carcinogenic, mutagenic and toxic properties1,2,3. Among the substances, phenol, which occurs naturally, is of particular interest4,5. Phenol is a key raw material that has been utilized in various applications across various fields6,7. Phenol is predominantly released into the environment through anthropogenic activities, including petrochemical refining, textile manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, leather tanning, dyes, paints, pesticides, and paper industries8,9,10. It is a highly toxic organic pollutant to the environment that cannot be removed through biological degradation. Phenol exposure, even at low concentrations, has been associated with severe health implications in humans, including neurotoxicity, protein denaturation, and potential damage to vital organs such as the liver, kidneys, and pancreas11. Therefore, it is crucial to eliminate phenols from water before consumption. As a result, numerous strategies rooted in physical, chemical, and biological processes have been innovated to eliminate phenolic compounds from aqueous environments. These methodologies encompass membrane-based separation technologies as reported by12,13,14, pressure-driven processes such as reverse and forward osmosis15, ion exchange mechanisms16, as well as electrochemical oxidation strategies17,18,19. Photocatalytic mechanisms20,21 and advanced oxidative techniques including photo-oxidation22, ozonation23, and the Fenton reaction24have been investigated for their efficacy. Biodegradation via microbial pathways25,26, phase transfer techniques such as liquid-liquid extraction27, and solid-phase extraction28have also shown promise. Additionally, adsorption-based methods remain widely utilized for phenol capture and removal29,30,31.

These methods exhibited several drawbacks, such as elevated expenses, intensive energy requirements, prolonged processing times, low removal efficiency and the generation of hazardous by-products32. Hence, with its high adsorption capacity, low cost, and potential for regeneration, adsorption has become the preferred method for phenol removal compared to the previously mentioned techniques33,34. Identifying an effective adsorbent is the biggest challenge for Scientists. Due to its excellent adsorption performance and proven efficiency, activated carbon remains the preferred adsorbent35,36. Lately, attention has shifted towards eco-friendly alternatives such as carbon-based adsorbents37,38. Bio-sorbents are effective, selective, and naturally attract pollutants. Furthermore, biosorption is extensively adopted for its low production cost and is readily available39. Biochar exhibits strong adsorption potential due to its large surface area, porous architecture, and abundance of surface functional groups. Several studies have investigated the use of biochar derived from agricultural residues for phenol removal from contaminated water. For instance, Pochampally et al. (2024)40 reported dye removal efficiencies exceeding 99% using biochars modified through a two-step treatment with KOH and 0.1 M H₃PO₄. Similarly, Kumar et al. (2021)41demonstrated that ball-milled wood apple shell biochar (WAS-BC) effectively adsorbed organic contaminants, including phenol, 4-chlorophenol (4-CPh), and 2,4-dichlorophenol (2,4-DCPh), from aqueous solutions. The maximum adsorption capacities (Qmax) were 102.71 mg/g for phenol, 172.24 mg/g for 4-CPh, and 226.55 mg/g for 2,4-DCPh.

The adsorption mechanisms for these phenolic pollutants include hydrogen bonding, π–π interactions, electrostatic attraction, ion exchange, and chemical adsorption. Fseha et al. (2023)42, investigated phenol removal using biochar produced from date palm fronds and leaves pyrolyzed at 600 °C (DPF600), reporting a maximum removal efficiency (64%) and adsorption capacity (15.93 mg/g). When applied to synthetic wastewater, DPF600 achieved removal efficiencies of 60% and 85%, with adsorption capacities of 241 mg/g and 22.28 mg/g for primary and secondary treated effluents, respectively. The main mechanisms responsible for phenol adsorption were identified as π–π interactions and hydrogen bonding. Zhou et al. (2023)43, studied phenol adsorption using wheat straw-derived biochar treated with hydrofluoric acid and activated at 900 °C under 10% \(\:{CO}_{2}\) to produce B-III-0.1D900. The biochar achieved 90% removal within 40 min and a maximum adsorption capacity of 471.16 mg/g, driven by electrostatic attraction and π–π interactions. Emenike et al. (2022)44, assessed the performance of biochar derived from Delonix regia pods for phenol removal from aqueous solution. Under optimal conditions of 60 °C and 60 min contact time, the biochar achieved a removal efficiency of 82.3%. Youcef et al. (2025)45,found that modified biochar from olive stones removed 83.65% of COD after 4 h of agitation, demonstrating strong treatment efficiency. Chebbi et al. (2023)46, reported that pine cone-derived biochar removed 96% of metronidazole from water, with an adsorption capacity of 19.26 mg/g, driven by pore-filling, which is defined by the diffusion of pollutants onto the surface and into the interior of biochar, hydrogen bonding, and electron donor–acceptor interactions. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have reported the use of biochar or activated carbon derived from Vicia Faba Stems as an adsorbent for phenol removal from aqueous solutions, although Vicia Faba has been used as a bioindicator for genotoxicity assessment of phenolic pollutants in wastewater (Liu et al., 2020)47. Hence, the purpose of this study was the development of a biochar derived from the Vicia faba stems and to evaluate its effectiveness as an adsorptive material for the removal of phenol from aqueous systems. The biochar was synthesized by Vicia faba stem biomass pyrolysis in one stage.

To thoroughly characterize the physicochemical properties of the resulting material, a suite of analytical techniques was employed, including Fourier Transform Infra-Red spectroscopy (FTIR), Scanning Electron Microscope(SEM) imaging, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area measurement, X-Ray Diffraction(XRD) analysis, and point of zero charge (pHPZC) determination. The performance of (VFS) in phenol elimination was assessed via a sequence of batch adsorption experiments. Both the effectiveness of phenol adsorption and the mechanism on VFS were investigated and analyzed. The experimental findings were then subjected to analysis, employing both kinetic models and adsorption isotherm models.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

All chemicals used in this study were analytical grade and applied without any additional purification(Aldrich, United States of America) with 99% of purity. The target adsorbate is the Phenol. It was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA and has a chemical formula of \(\:{C}_{6\:}{H}_{5}OH\), 96%, MW of 94,11 g/mol, density of 1.07 g/cm3, solubility in water as 85 0.700 at 25 C° g/L at 25 °C. Deionised water was utilised for the preparation of all test solutions, and the solution pH was adjusted using either hydrochloric acid (HCl) or sodium hydroxide (NaOH), as necessary.

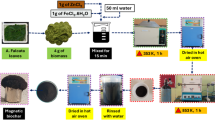

Synthesis of biochar from vicia fabastem

Vicia Faba stems were collected from Djemorrah, Biskra, Algeria. They were washed with tap water until clean, then soaked in distilled water to remove any remaining impurities, and finally air-dried. The material was crushed, oven-dried at 105–110 °C for 24 h, and screened to obtain particles within the 1–2 mm size range. The adopted carbonization was performed at 600 °C for two hours under oxygen-limited conditions. The biochar obtained was immersed in a 0.1 M HCl solution to eliminate any residual minerals. Afterwards, it was thoroughly rinsed with distilled water until the filtrate reached a near-neutral pH (6–7). Finally, the biochar underwent a drying process at temperatures ranging from 105 to 110 °C for a duration of 24 h, and the (VFSB) was ready for adsorption experiments.

Properties of VFS material

A comprehensive characterization of the prepared VFSB was conducted to investigate its structural, textural, and morphological properties. The crystallographic structure was characterized through X-ray diffraction analysis, utilizing a diffractometer outfitted with a goniometer and operating under CuKαradiation at 40 kV voltage and 30 mA current. The diffraction pattern was recorded across a 2θ range extending from 10° to 90°, with a scan speed of 2 degrees per minute. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with EDX (EDEX AMETEK)was performed to analyze the morphology, elemental composition, and particle size of the samples. The presence and nature of the chemical functionalities within the synthesized adsorbent were identified via FTIR spectroscopic analysis, conducted using an Agilent MicroLab equipment. All the Samples were scanned in the 400–4000 cm⁻¹ range, the KBr disc technique was employed, with a weight ratio of 1/100.The porous architecture of the synthesized adsorbent was characterized at 77.31 K through nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms using an ASAP 2020 analyser. The specific surface area (SBET) and overall pore volume (VTotal) were derived via the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) approach, while pore size distribution was evaluated through the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) model. The point of zero charge (pHPZC) was assessed by a previously reported method48, in which 50 mL of 0.01 M NaCl solution was titrated to a pH range of 2 to 12 using standardized HCl or NaOH solutions. Then, 50 mg of VFS-biochar was added to each solution, which was stirred overnight at room temperature. After the measurement of the final pH of each sample, the pHPZC value was determined from the intersection of the curve generated by plotting the net pH change (pHf – pH\(^\circ\) versus pH\(^\circ\).

Batch adsorption trials

Adsorption experiments were carried out using magnetic stirring, where a predetermined amount of biochar was added to 50 mL phenol solutions. After the adsorption phase, the mixtures were filtered under vacuum using membranes with a pore diameter of 0.45 mm. Various parameters influencing the adsorption process were systematically examined.

-

Adsorption Kinetics: Time-dependent adsorption of phenol was explored by sampling at intervals from 5 min to 240 min. The study was carried out using a phenol solution initially concentrated at 50 mg L⁻¹, with biochar applied at 0.05 g L⁻¹.

-

Influence of Initial Solution pH: The effect of varying pH levels (2–12) was investigated using 0.1 M hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide for adjustment. Each test maintained a phenol concentration of 50 mg/L and a biochar dosage of 0.05 g/L.

-

Influence of Initial Pollutant Concentration: To examine adsorption isotherms, the initial concentration of phenol was varied between 10 and 110 mg/L. The experiments were performed at a controlled temperature of 20 °C, with contact time fixed based on the equilibrium duration established in the kinetic studies.

-

Adsorbent Dosage Effect: The influence of biochar quantity on phenol removal efficiency was assessed by altering the biochar dose from 0.05 to 0.09 g/L, while keeping phenol levels fixed at 50 mg/L. All trials were carried out at 20 °C.

-

Impact of Temperature: The thermodynamic behavior of the adsorption process was studied by performing experiments at four different temperatures (20, 30, 40, and 50 °C). Phenol concentrations ranged from 10 to 110 mg/L, and the biochar dosage was consistently fixed at 0.05 g/L.

The adsorption capacities of phenol on VFSB (qt (mg.g−1)) at time t, the equilibrium (qe (mg g-1)), and the efficiency of phenol removal (%) were evaluated by Eqs. (1)-(3).

In this context, C₀, Cₑ and Ct represent the phenol concentrations at the initial time, at equilibrium, and at time t, respectively. The variables m (in grams) and V (in liters) denote the mass of VFSB added and the volume of the sample being tested, respectively.

The kinetic analysis provided insights into the progression of adsorption efficiency over time, allowed for the determination of the equilibrium time, and facilitated the identification of the dominant adsorption mechanisms. This was achieved by fitting the experimental data to two widely recognized kinetic models: the pseudo-first-order model proposed by Lagergren (1898)49. and the pseudo-second-order model developed by Ho et al. (2000)50. The corresponding equations for these models are outlined in Table 1.

The statistical indicators Chi-square (χ²) and the coefficient of determination (R²) were employed to evaluate the accuracy of the adsorption model fits by comparing the predicted adsorption capacities (qe, cal) with the experimentally measured values (qe, exp). As described in Eq. (4), an R² value approaching 1 signifies a strong correlation between the model and experimental data. Similarly, as outlined in Eq. (5), a lower χ² value indicates minimal deviation between predicted and observed results. Together, a high R² and a low χ² denote a more accurate and reliable model fit51.

Coefficient of determination :

Chi-square :

The variables (qe, exp) and (qe, cal) denote the equilibrium adsorption capacities. The term (qe, mean) refers to the mean value of the experimentally observed (qe, exp) measurements, while (N) indicates the total number of experimental repetitions performed.

Evaluation of VFS-biochar regeneration performance

Evaluating the long-term usability of an adsorbent is essential from both environmental and cost perspectives. To assess the regeneration performance of VFS-biochar, four consecutive adsorption cycles were carried out, incorporating desorption and regeneration steps based on the method outlined by Azri et al. (2022)52. For each cycle, 200 mg of the biochar was introduced into a 40 mg/L phenol solution and agitated at 300 rpm for 4 h. After each run, the saturated biochar was dried and then reapplied in the next cycle. Once phenol removal efficiency dropped below 50%, the used adsorbent was submerged in 100 mL of 0.1 M NaOH for 4 h to induce desorption, followed by thorough rinsing with ultrapure water. The cleaned material was dried again before further regeneration trials. Phenol removal efficiency at equilibrium was determined using the formula (3) above-mentioned.

Results and discussion

Assessment of material properties

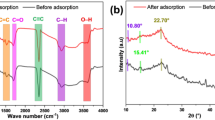

The Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infra-Red spectroscopy(ATR-FTIR) spectrum of the synthesized VFS-derived biochar (VFSB), shown in Fig. 1, highlights the presence of various surface functional groups potentially responsible for interactions with phenol molecules in aqueous solution. Evidence of such interactions was obtained by comparing the FTIR spectra before and after the adsorption process. Notably, the observed shift in peak positions or reduction in intensity, particularly around 3429 cm⁻¹, corresponds to (–OH and –\(\:NH_2\) groups) suggests the occurrence of hydrogen bonding as a result of the interaction between phenol and the chemically active groups on the biochar surface. Hydroxyl groups (OH), which are key participants in hydrogen bonding, were confirmed through peaks at 3776 and 3434 cm⁻¹, consistent with previous findings53. A broad absorption band around 1632 cm⁻¹ was assigned to C = C bonds, aligning with interpretations by Iles et al. (2024)54. Additionally, C–H stretching vibrations of aliphatic acids were identified at 2847 and 2924 cm⁻¹55,56. Atmospheric CO₂ is reflected by the weak absorption peak at 2359 cm⁻¹57,58. A well-observed sharp peak observed at 747 cm⁻¹ was linked to C–H vibrational modes in aromatic rings59, indicating aromatic character on the biochar surface.

We show in Fig. 2 SEM imaging which illustrates the morphology of VFSB, revealing a highly porous and irregular surface texture, which is indicative of a high specific surface area. Complementary elemental analysis via EDX confirmed that the biochar primarily consists of carbon (83.1 at%) and oxygen (16.1 at%).

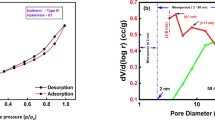

Surface area and porosity characteristics were examined through BET analysis, which showed that VFSB possesses a specific surface area (SBET) of 144.34 m²/g and an average pore diameter of 43.367 Å (4.34 nm), indicating well-developed porosity. The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms, shown in Fig. 3(a), revealed a hysteresis loop within the relative pressure range (P/P\(^\circ\) of 0.4 to 0.8. This hysteresis behavior is indicative of physisorption, suggesting that nitrogen gas was adsorbed without external desorption agents under controlled conditions. Figure 3also details a pore structure composed of both micro- and mesopores, with a predominance of mesopores (ranging between 2 and 50 nm). Based on classification criteria from (Schwanke et al. 2017)60, pores below 2 nm are microporous, while those between 2 and 50 nm fall under mesoporous. Therefore, VFSB is best categorized as a mesoporous material with a non-uniform pore system.

Lastly, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, as depicted in Fig. 4(b), was conducted to investigate the crystallographic nature of the biochar, specifically distinguishing between amorphous and crystalline phases. XRD analysis reveals a broad, featureless profile with no distinct peaks, confirming the amorphous nature of the biochar. A wide signal centred at 22.29°, within the 20°–30° region, aligns with the (002) diffraction plane, typically reflecting the disordered arrangement of aromatic carbon layers. The pronounced symmetry of this feature, coupled with the absence of γ-band reflections, indicates minimal presence of non-aromatic and aliphatic domains, consistent with findings by Huang et al. (2009) and Yan et al. (2021)61,62. Additionally, A diffraction peak around 41° corresponding to the (100) plane was detected, pointing to graphitic and hexagonal carbon structures. This feature reflects the presence of aromatic carbon layers, with lateral dimensions indicative of graphitic domains63,64. Moreover, the point of zero charge (pHPZC) for VFSB, shown in Fig. 4(a), sheds light on the material’s surface charge characteristics under various pH conditions. With a pHPZC of around 6.0, the biochar surface is positively charged at pH values below 6.0 and negatively charged at higher pH, a transition crucial for electrostatic adsorption of pollutants.

Adsorption kinetics

To better understand the adsorption behavior of phenol on VFSB, the experimental kinetic data were evaluated using two widely accepted models: the pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) models.

Figure 5; Table 2 collectively indicate that both models demonstrated strong agreement with the experimental data, reflected by high coefficients of determination (R²). However, the PSO model exhibited superior fitting performance, with an R² value of 0.992 and a low sum of squared errors (SSE) of 2.162. The observed high degree of correlation underscores the importance of chemisorption as a dominant mechanism governing the uptake of phenol onto VFSB. Similar adsorption behaviors have been documented in various biochar materials synthesized from diverse sources such as paper sludge, wheat husk, Hizikia fusiformis, and microalgae, each exhibiting comparable kinetic patterns in their interaction with phenolic contaminants65,66,67.

The adsorption capacity of VFSB was positively influenced by increasing contact time, with a gradual enhancement until equilibrium was achieved. A contact time of 180 min was identified as the equilibrium point at which the system exhibited its highest phenol removal performance, achieving 88.86% elimination and a maximum adsorption capacity of 44.25 mg g⁻¹, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Where qt and qe (mg/g) are the amounts of phenol at a specific time and at equilibrium, respectively. K1 (min − 1), K2 (g (min − 1 mg − 1)) are the constants of PFO and PSO, respectively.

Effect of pH on phenol adsorption

The adsorption experiments across a wide pH range (2–12) were conducted and reported. The highest removal efficiency (about 88.86%) was observed at pH 6, which is why emphasis was placed on this condition. As shown in Fig. 6, phenol removal is higher at pH˂pka. Sorption capacity increased with an increase pH of the solution from 2.0 to 6.0 and thereafter decreased with a further increase in the pH value. At the optimum pH of 6.0, phenol, the maximum adsorption capacity of phenol was calculated to be 44.43 mg/g. The pKa value of phenol is 9.95. Figure 8 shows that the acidic nature of pH solution in the range of 2–6 is favorable for the phenol adsorption process. It is evident from Fig. 7 that under acidic conditions, phenol remains undissociated, and adsorption is mainly driven by dispersion interactions. Between pH 2 and 6, adsorption increases slightly, but a decline is observed from pH 6 to 7 onward. At alkaline pH, phenol uptake is reduced, likely due to electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged adsorbent surface and phenolate anions in solution, as also reported by68,69. At low pH, protonation of the carbon surface limits phenol interaction, leading to lower adsorption. The pKa of phenol at room temperature is approximately 9.0, indicating that above this pH phenol exists primarily in its ionized form, which enhances solubility in water and decreases adsorption.

Adsorption isotherms

The equilibrium isotherm analysis of phenol adsorption onto VFSB reveals key details about the adsorption mechanism and the nature of interactions at equilibrium, occurring on the biochar surface. Figure 7 shows the equilibrium adsorption pattern, and Table 3 lists the parameters from the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin models.

The obtained isotherm parameters in Table 3 indicate that all three models provided a satisfactory fit to the experimental data, with coefficients of determination (R²) exceeding 0.9. Among them, the Freundlich model exhibited the best correlation, characterized by an R² of 0.972 and a chi-square (χ²) value of 4.327. This strong alignment with the Freundlich model implies that the adsorption process occurs on a heterogeneous surface through multilayer adsorption, which corresponds well with the morphological features observed in SEM analysis, particularly the heterogeneous and fine-pore structure of VFSB. The Freundlich constant (n = 2.217), exceeding the value of 1, suggests that the adsorption process is favourable under the studied conditions. Similar n values above 1 have also been reported in earlier research70,71,72. While the Freundlich model provided the best overall fit, the Langmuir model estimated the highest monolayer adsorption capacity, with a Qmax of 47.473 mg g⁻¹. This capacity is influenced by both the physicochemical features of the adsorbent and the starting concentration of phenol. For a broader context, Table 4 presents a comparative analysis of the maximum adsorption capacities (Qmax) of VFSB with those of various biochars reported in prior studies.

Thermodynamic investigation

This section of the work focuses on the evaluation of thermodynamic characterization of the adsorption process, which are crucial for the interpretation of the nature of the adsorption mechanism, specifically, it explores whether the adsorption occurs spontaneously, whether the process absorbs or releases heat (i.e., is endothermic or exothermic), and how it influences molecular disorder at the interface between the adsorbent and the aqueous phase. These parameters also aid in understanding the adsorption mechanisms, allowing distinction whether the underlying mechanism is dominated by physical or chemical interactions35,73,74. In this investigation, the standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°), enthalpy change (ΔH°), and entropy change (ΔS°) were determined. Equation (6) to (8) were applied to calculate these thermodynamic values within this study.

By substituting Eq. (6) into Eq. (7), the resulting equation is referred to as the Van’t Hoff relation (Eq. (8)).

The thermodynamic parameters analyzed include ΔG° (kJ/mol), denoting the variation in Gibbs free energy; ΔH° (kJ/mol), representing the enthalpy change; and ΔS° (J/mol·K), corresponding to the entropy change. In these calculations, R denotes the universal gas constant with a value of 8.314 J/mol·K, while T signifies the absolute temperature of the solution, expressed in Kelvin.

As shown in Table 4, the Gibbs free energy ΔG° ranged from − 2808.72 to − 1836.19 kJ/mol, with all values being negative. This confirms that the adsorption process occurred spontaneously and was energetically favourable. The positive ΔH° values reported in Table 5 and illustrated in Fig. 8a and b indicate that phenol adsorption is endothermic, involving heat intake from the environment and resulting in increased internal energy within the system. Previous investigations by Zhou et al. (2018)75 and Kalderis et al. (2017)67 demonstrated that phenolic pollutants undergo spontaneous and endothermic adsorption when treated with magnetic and lignocellulosic biochars, indicating consistent thermodynamic behavior across varying sorbent materials. According to Lee et al. (2019)20, the adsorption process yields a favourable increase in entropy (ΔS° > 0), which reflects heightened disorganization at the solid-liquid interface and implies the absence of structural ordering by phenol during adsorption.

Assessment of the reuse potential of the synthesized biochar

The reusability of such an adsorbent describes its capacity to undergo regeneration and be applied in successive cycles. The outcomes of the adsorption–regeneration tests for VFS-biochar are shown in Fig. 9. Phenol removal efficiency declined from 88.86% in the first cycle to 47.31% by the fourth cycle.This reduction may result from the gradual depletion of active sites and surface saturation of the adsorbent over successive adsorption cycles52.During the initial adsorption cycle, phenol molecules occupy part of the active sites and remain partially bound, influencing subsequent adsorption cycles. Experimental results show that after desorption using 0.1 M NaOH solution, VFS-biochar maintains effective performance, achieving a phenol removal rate of around 81.22% in the first cycle post-desorption. These findings highlight VFS-biochar as a reusable, cost-effective, and practical adsorbent for phenol removal from water.

Adsorption mechanism

The affinity of an adsorbent for target compounds depends on its surface functional groups and point of zero charge (pHpzc). The pHpzc represents the pH at which the adsorbent surface has no net electrical charge. It reflects the surface’s electronic properties and the presence of oxygen-containing functional groups. When the solution pH is below the pHpzc (pH < pHpzc), the concentration of H⁺ ions is higher than that of OH⁻, giving the adsorbent surface a net positive charge, which promotes the attraction of negatively charged species (anions).

However, adsorption affinity is not governed solely by functional groups and pHpzc. The relatively high surface area of VFS biochar (144.34 m²/g) and its porous structure provide abundant active sites for pore filling and physical adsorption, which enhance uptake capacity. Electrostatic interactions also contribute, especially as solution pH changes relative to the biochar’s pHpzc (6.0). At acidic pH, reduced electrostatic repulsion favors adsorption, whereas at alkaline pH, the predominance of negatively charged phenolate ions and the negatively charged biochar surface lead to lower uptake.

Adsorption of organic compounds onto carbons generally involves three major types of interactions with phenol: (i) π–π interactions, (ii) electron donor–acceptor (EDA) complex formation, and(iii) hydrogen bonding82.These mechanisms often operate simultaneously. Oxidation during biochar preparation can introduce acidic functional groups, such as carboxyl and phenolic groups, which reduce the π-electron density in the carbon structure. This reduction can limit phenol adsorption due to a weaker interaction with the aromatic ring. However, surface oxygen groups in π-electron-rich zones can still form complexes with phenol’s aromatic rings, supporting π–π interactions. Chebbi et al.45 also noted that π–π interactions play a role in the adsorption of aromatic pollutants like metronidazole. The pHpzc of the prepared VST-biochar was measured at 6, indicating a slightly acidic nature.In our study, the solution pH was 6, which matches the pHpzc of the synthesized biochar. At this pH, the biochar surface carries almost no net charge. Additionally, phenol exists mainly in its neutral form (pKa = 9.9), meaning electrostatic forces are negligible. Therefore, phenol adsorption in this case depends primarily on non-electrostatic mechanisms. The dominant interactions observed were π–π stacking, hydrogen bonding, Van der Waals forces, and pore filling.

Conclusion

In this framework, wefocus on producing a cost-effective adsorbent from Vicia faba stem biomass via direct pyrolysis at 600 °C, aiming to valorise agricultural waste and assess its potential for phenol removal from water. The resulting biochar was characterized using BET, SEM, FTIR, XRD, and pHpzc analyses. The specific surface area was measured at 144.34 m²/g. Experimental results indicated that the highest phenol removal efficiency, 88.86%, was achieved at pH 6 under acidic conditions.The findings demonstrate that equilibrium in the phenol adsorption process was attained within three hours, yielding a removal rate of approximately 88.86%. Kinetic modelling revealed that the pseudo-second-order (PSO) model provided an excellent fit to the experimental data at a concentration of 0.05 g L⁻¹, suggesting that chemisorption is the dominant mechanism. The adsorption behavior was best represented by the Freundlich isotherm model, implying that phenol molecules interacted with a heterogeneous surface in a multilayer adsorption pattern. Additionally, the thermodynamic analysis indicated that the adsorption was both endothermic and spontaneous. The Phenol adsorption was governed by a combination of π–π interactions, hydrogen bonding, and pore-filling mechanisms. The reusability test showed that VFS-biochar can be applied across several cycles, demonstrating its cost-effectiveness. Future studies could aim to enhance its surface properties and regeneration efficiency to improve its adsorption performance for phenol and other organic contaminants. Further research may also assess its effectiveness in treating complex mixtures with multiple pollutants and explore its practical application in real wastewater treatment systems.

Challenges and future prospects

Challenge | Possible research direction/innovation |

|---|---|

Limited surface area and pore structure | Surface activation, chemical modification, or nanocomposite integration |

Regeneration efficiency decreases after multiple cycles | Development of low-energy, green regeneration methods |

Performance tested mainly on single-contaminant systems | Evaluation under real wastewater conditions with multiple pollutants |

Adsorption efficiency varies with pH and water chemistry | Design of modified biochar with specific surface functional groups |

Uncertainty persists regarding large-scale application and cost-effectiveness | Integrated assessments of technology performance, cost, and environmental impact |

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bacha, N. & Achour, S. Impact of the combination of aluminum sulphate/activated carbon powder on the removal of refractory organic micropollutants by coagulation-flocculation. LARHYSS J. 33, 209–220 (2018). (in French).

Elwakeel, K. Z., Aly, M. H., El-Howety, M. A., El-Fadaly, E. & Al-Said, A. Synthesis of Chitosanactivated carbon beads with abundant amino groups for capture of Cu(II) and Cd(II) from aqueous solutions. J. Polym. Environ. (. 26, 3590–3602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-018-1243-2 (2018).

Elwakeel, K. Z., El-Sayed, G. O. & Abo El-Nassr, S. M. Removal of ferrous and Manganous from water by activated carbon obtained from sugarcane Bagasse. Desalin. Water Treat. 55, 471–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443994.2014.919606 (2015).

Pradeep, N. V. et al. Biological removal of phenol from wastewaters: a mini review. Appl. Water Sci. 5, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-014-0176-8 (2015).

Yuan, Z., Nag, R. & Cummins, E. Human health concerns regarding micro plastics in the aquatic environment –From marine to foodsystems. Sci. Total Environ. 823, 153730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153730 (2022).

Al-Kindi, G. & Al Ani, F. Study the catalytic oxidation of phenol in both baskets stirred tank and packed bed reactors. Eng. Technol. J. 37, 175–185. https://doi.org/10.30684/etj.37.1C.2 (2019).

Mohammed, N. A. S., Abu-Zurayk, R. A., Hamadneh, I. & Al-Dujaili, A. H. Phenol adsorption on Biochar prepared from the pine fruit shells: equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamics studies. J. Environ. Manage. 226, 377–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.08.033 (2018).

Kalogianni, A. I., Lazou, T., Bossis, I. & Gelasakis, A. I. Natural phenolic compounds for the control of oxidation, bacterial spoilage, and foodborne pathogens in meat. Foods.9(6), 794 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9060794

Ali, A., Bilal, M., Khan, R., Farooq, R. & Siddique, M. Ultrasoundassisted adsorption of phenol from aqueous solution by using spent black tea leaves. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 25 (23), 22920–22930. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-2186-9 (2018).

Younis, A. M., Elkady, E. M. & Saleh, S. M. Novel eco-friendly aminomodified nanoparticles for phenol removal from aqueous solution. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 27 (24), 30694–30705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09313-y (2020).

Sarker, N. & Fakhruddin, A. N. Removal of phenol from aqueous solution using rice straw as adsorbent. Appl. Water Sci. 7 (3), 1459–1465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-015-0324-9 (2017).

Li, Y., Wei, J., Wang, C. & Wang, W. Comparison of phenol removal in synthetic wastewater by NF or RO membranes. Desalin. Water Treat. 22, 211–219. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2010.1787 (2010).

Zagklis, D. P., Vavouraki, A. I., Kornaros, M. E. & Paraskeva, C. A. Purification of Olive mill wastewater phenols through membrane filtration and resin adsorption/desorption. J. Hazard. Mater. 285, 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.11.038 (2015).

Huang, J. J. et al. Electrospray-printed three-tiered composite membranes with enhanced mass transfer coefficients for phenol removal in an aqueous-aqueous membrane extractive process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 7611–7618. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c00475 (2020).

Cui, Y. et al. Removal of organic micro-pollutants (phenol, aniline and nitrobenzene) via forward osmosis (FO) process: evaluation of FO as an alternative method to reverse osmosis (RO). Water Res. 91, 104–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2016.01.001 (2016).

Víctor-Ortega, M. D., Ochando-Pulido, J. M. & Martínez-Férez, A. Phenols removal from industrial effluents through novel polymeric resins: kinetics and equilibrium studies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 160, 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2016.01.023 (2016).

Yavuz, Y. & Koparal, A. Electrochemical oxidation of phenol in a parallel plate reactor using ruthenium mixed metal oxide electrode. J. Hazard. Mater. 136, 296–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.12.018 (2006).

Abdelwahab, O., Amin, N. K. & El-Ashtoukhy, E. S. Z. Electrochemical removal of phenol from oil refinery wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 163, 711–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.07.016 (2009).

Garcia-Segura, S., Ocon, J. D. & Chong, M. N. Electrochemical oxidation remediation of real wastewater effluents - a review. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 113, 48–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. psep.2017.09.014 (2018).

Lee, C. G. et al. Porous electrospun fibers embedding TiO2 for adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of water pollutants. Environ Sci. Technol. 52 (7), 4285–4293. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b06508 (2018).

Mohamed, A. et al. Rapid photocatalytic degradation of phenol from water using composite nanofibers under UV. Environ. Sci. Eur. 32, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-00436-0 (2020).

Brillas, E. & Garcia-Segura, S. Benchmarking recent advances and innovative technology approaches of Fenton, photo-Fenton, electro-Fenton, and related processes: a review on the relevance of phenol as model molecule. Sep. Purif. Technol. 237 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2019.116337 (2020).

Ma, C., Jia, S., Yuan, P. & He, Z. Catalytic ozonation of 2, 2′-methylenebis (4-methyl-6-tert-butylphenol) over nano-Fe3O4@cow Dung Ash composites: optimization, toxicity, and degradation mechanisms. Environ. Pollut. 265 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114597 (2020).

Shaida, M. A., Sen, A. K. & Dutta, R. K. Alternate use of sulphur rich coals as solar photo-Fenton agent for degradation of toxic Azo dyes. J. Clean. Prod. 195, 1003–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.05.286 (2018).

Villegas, L. G. C., Mashhadi, N., Chen, M., Mukherjee, D. & Taylor, K. E. Biswas, N. A short review of techniques for phenol removal from wastewater. Curr. Pollut Rep. 2, 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40726-016-0035-3 (2016).

Tomei, M. C., Angelucci, D. M., Clagnan, E. & Brusetti, L. Anaerobic biodegradation of phenol in wastewater treatment: achievements and limits. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-021-11182-5 (2021).

Zhu, G. et al. An ionic liquid functionalized polymer for simultaneous removal of four phenolic pollutants in real environmental samples. J. Hazard. Mater. 373, 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.03.101 (2019).

Yang, G. et al. Effective degradation of phenol via catalytic wet peroxide oxidation over N, S, and Fe-tridoped activated carbon. Environ. Pollut. 258, 113687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113687 (2020a).

Liu, Q. S., Zheng, T., Wang, P., Jiang, J. P. & Li, N. Adsorption isotherm, kinetic and mechanism studies of some substituted phenols on activated carbon fibers. J Chem Eng. 157 (2–3), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2009.11.013 (2010).

Singh, R., Naik, D. V., Dutta, R. K. & Kanaujia, P. K. Biochars for the removal of naphthenic acids from water: a prospective approach towards remediation of petroleum refinery wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 266 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121986 (2020).

Azari, A., Yeganeh, M., Gholami, M. & Salari, M. The superior adsorption capacity of 2,4-Dinitrophenol under ultrasound-assisted magnetic adsorption system: modeling and process optimization by central composite design. J Hazard. Mater 418, 126348 (2021a). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126348

El-Chaghaby, G. A., Ramis, E. S. & Ahmad, A. F. Rice straw and rice straw Ash for the removal of brilliant green dye from wastewater. Asian J. Appl. Chem. 15, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.9734/AJACR/2018/41958 (2018).

Alkaram, U., Mukhlis, F. & Al-Dujaili, A. A. The removal of phenol from aqueous solutions by adsorption using surfactant-modified bentonite and kaolinite. J. Hazard. Mater. 169, 324–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.03.153 (2009).

Yang, K., Yang, J., Jiang, Y., Wu, W. & Lin, D. Correlations and adsorption mechanisms of aromatic compounds on a high heat temperature treated bamboo Biochar. Environ. Pollut. 210, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2015.12.004 (2016).

Polat, H., Molva, M. & Polat, M. Capacity and mechanism of phenol adsorption on lignite. Int. J. Min. Process. 79 (4), 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.minpro.2006.03.003 (2006).

Lin, S. H. & Juang, R. S. Adsorption of phenol and its derivatives from water using synthetic resins and low-cost natural adsorbents: a review. J. environ. Manag. 90 (3), 1336–1349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.09.003 (2009).

Lee, C. G., Hong, S. H., Hong, S. G., Choi, J. W. & Park, S. J. Production of Biochar from food waste and its application for phenol removal from aqueous solution. Water Air Soil. Poll. 230, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-019-4125-x (2019).

Lawal, A. A. et al. One-step steam pyrolysis for the production of mesoporous Biochar from oil palm frond to effectively remove phenol in facultatively treated palm oil mill effluent. Environ. Tech. Innov. 18, 100730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2020.100730 (2020).

Sabzehmeidani, M. M., Mahnaee, S., Ghaedi, M., Heidari, H. & Roy, V. A. Carbon based materials: a review of adsorbents for inorganic and organic compounds. Mater. Adv. 2 (2), 598–627. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0MA00087F (2021).

Pochampally, S. V., Blanco, J. G., Ayalew, K., Murph, S. E. H. & Moon, J. Novel alkali intercalated and acid-exfoliated biochars with enhanced surface areas for contaminant adsorption applications. Sep. Purif. Technol. 350, 127793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.127793 (2024).

Kumar, N. S., Shaikh, H. M., Asif, M. & Al-Ghurabi, E. H. Engineered Biochar from wood Apple shell waste for high-efficient removal of toxic phenolic compounds in wastewater. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 2586 (2021).

Fseha, Y. H., Shaheen, J. & Sizirici, B. Phenol contaminated municipal wastewater treatment using date palm frond biochar: optimization using response surface methodology. Emerg. Contaminants. 9 (1), 100202 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Adsorption and mechanism study for phenol removal by 10% CO2 activated bio-char after acid or alkali pretreatment. J. Environ. Manage. 348, 119317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119317 (2023).

Emenike, E. C. et al. Delonix regia Biochar potential in removing phenol from industrial wastewater. Bioresour Technol. Rep. ;19, 101195 (2022).

Youcef, S. et al. Chemical oxygen demand (COD) reduction in wastewater from the textile industry by coagulation-flocculation and adsorption. Environ. Monit. Assess. 197 (5), 536 (2025).

Chebbi, M., Ounoki, S., Youcef, L. & Amrane, A. Synthesis and characterization of pine cones Biochar for the removal of an antibiotic (Metronidazole) from aqueous solutions. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 126, 327–339 (2023).

Liu, Y., Liu, Y. J. & Liu, J. Study on the removal effects and genotoxicity evaluation of phenols in a semi-coking wastewater treatment stages. J. Water Chem. Technol. 42 (4), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1063455X20040086 (2020).

Hadj-Otmane, C., Ouakouak, A., Youcef, L. & NguyenTran One-stage Preparation of palm petiole-derived biochar: characterization and application for adsorption of crystal Violet dye in water. Environ. Tech. Innov. 19, 100872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2020.100872 (2020).

Lagergren, S. About the theory of so-called adsorption of soluble substances. Kungliga Svenska VetenskapsakademiensHandlingar. 24, 1–39 (1898).

Ho, Y. S. & McKay, G. The kinetics of sorption of divalent metal ions onto sphagnum moss peat. Water Res. 34, 735–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1354(99)00232-8 (2000).

Benaoune, S. et al. Dual-Activated Tamarix Gallica-Derived Carbons for Enhanced Glyphosate Adsorption: A Comparative Study of Phosphoric and Sulfuric Acid Activation. Materials.18(3), 511 (2025). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18030511

Azri, N. et al. Development of a novel and efficient Biochar produced from pepper stem for effective ibuprofen removal. Bioresour Technol. 347, 126685 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. X. Biochar surface complexation and Ni (II), Cu (II), and cd (II) adsorption in aqueous solutions depend on feedstock type. Sci. Total Environ. 712, 136538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136538 (2020).

Iles, A., Zaoui, F., Daouadji, B. E., Zorgani, M. A., Siddig, L. A., Abdelhamid,A. S., … Saleh, N. I. Removal of pollutants by olive stones-derived activated carbon@Fe3O4 nanocomposites: Effect of calcination temperature on adsorption properties.J.Water. Process. Eng. 66, 105960(2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.105960.

Wafaa, Y. et al. Mechanistic insights into methylene blue removal via Olive stone-activated carbon: A study on surface porosity and characterization. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 27 (5), 101692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jscs.2023.101692 (2023).

Magioglou, E., Frontistis, Z., Vakros, J., Manariotis, I. D. & Mantzavinos, D. Activation of persulfate by biochars from valorized Olive stones for the degradation of sulfamethoxazole. Catalysts 9 (5), 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal9050419 (2019).

Ni, X., Sun, X., Xu, Y. & Xu, D. A green and facile synthesis of Nosean composite from coal Fy Ash for optimizing Rhodamine B adsorption using response surface methodology. J. Water Chem. Technolo. 42 (4), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1063455X20040086 (2020).

Salem, D. B. et al. Easy separable, floatable, and recyclable magnetic-biochar/alginate bead as super-adsorbent for adsorbing copper ions in water media. Biores Technol. 383, 129225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2023.129225 (2023).

Nadolny, B. et al. Use of brewing industry waste to produce carbonbased adsorbents: Paracetamol adsorption study. J. Environ. Sci. Health A. https://doi.org/10.1080/10934 (2020).

Schwanke, C. et al. Correlating oxygen evolution catalysts activity and electronic structure by a high-throughput investigation of Ni1-y-zFeyCrzOx. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 44192. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44192 (2017).

Huang, Y. et al. Effects of metal catalysts on CO2 gasification reactivity of biomass Char. Biotechnol. Adv. 27 (5), 568–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bio (2009).

Yan, Y., Manickam, S., Lester, E., Wu, T. & Pang, C. H. Synthesis of graphene oxide and graphene quantum Dots from miscanthus via ultrasound-assisted mechano-chemical cracking method. Ultrason. Sonochem. 73 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105519 (2021).

Lu, L., Kong, C., Sahajwalla, V. & Harris, D. Char structural ordering during pyrolysis and combustion and its influence on Char reactivity. Fuel 81 (9), 1215–1225. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-2361(02)00035-2 (2002).

Mohan, D., Abhishek, K., Sarswat, A., Patel, M. S. P. & Pittman, C. U. Biochar production and applications in soil fertility and carbon sequestration – a sustainable solution to crop-residue burning in India. RSC.Adv. 8(1):508–520 doi: 10. 1039/c7ra10353k (2018).

Shin, W. S. Adsorption characteristics of phenol and heavy metals on Biochar from Hizikia fusiformis. Environ. Earth Sci. 76 (22). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-017-7125-4 (2017).

Zheng, H. et al. Adsorption of p-nitrophenols (PNP) on microalgal biochar: analysis of high adsorption capacity and mechanism. Biores Technol. 244 (Pt 2), 1456–1464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.025 (2017).

Kalderis, D., Kayan, B., Akay, S., Kulaksız, E. & Gözmen, B. Adsorption of 2,4-dichlorophenol on paper sludge/ wheat husk biochar: process optimization and comparison with biochars prepared from wood chips, sewage sludge and hog fuel/demolition waste. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 5 (3), 2222–2231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2017.04.039 (2017).

Hameed, B. H. & Rahman, A. A. Removal of phenol from aqueous solutions by adsorption onto activated carbon prepared from biomass material‖. J. Hazard. Mater. 33 160 (2–3), 576–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.03.028 (2008).

Moreno-Castilla, C. Adsorption of organic molecules from aqueous solutions on carbon materials‖. Carbon N Y. 42 (1), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2003.09.022 (2004).

Poots, A., Mckay, G. & Healy, J. J. All use subject to JSTOR terms and conditions removal from using of effluent wood basic as an dye adsorbent. J. Water Pollut Control Fed. 50 (5), 926–935 (1978). http://www.jstor.org/stable/25039656

Mittal, A., Mittal, J., Malviya, A., Kaur, D. & Gupta, V. K. Adsorption of hazardous dye crystal Violet from wastewater by waste materials. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 343 (2), 463–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2009.11.060 (2010).

Imran, M. S., Javed, T., Areej, I. & Haider, M. N. Sequestration of crystal Violet dye from wastewater using low-cost coconut husk as a potential adsorbent. Water Sci. Technol. 85 (8), 2295–2317. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2022.124 (2022).

Vithanage, M., Mayakaduwa, S. S., Herath, I., Ok, Y. S. & Mohan, D. Kinetics, thermodynamics and mechanistic studies of Carbofuran removal using biochars from tea waste and rice husks. Chemosphere 150, 781–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.11.002 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Adsorption characteristics and mechanism of sewage sludge-derived adsorbent for removing sulfonated Methyl phenol resin in wastewater. RSC Adv. 5 (93), 76160–76169. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA17125C (2015).

Zhou, X. et al. Preparation of magnetic Biochar derived from cyclosorus interruptus for the removal of phenolic compounds: characterization and mechanism. Sep. Sci. Technol. 53 (9), 1307–1318. https://doi.org/10.1080/01496395.2018.1444056 (2018).

Anirudhan, T. S., Sreekumari, S. S. & Bringle, C. D. Removal of phenols from water and petroleum industry refinery effluents by activated carbon obtained from coconut Coir pith. Adsorption 15, 439–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10450-009-9193-6 (2009).

Altenor, S. et al. Adsorption studies of methylene blue and phenol onto vetiver roots activated carbon prepared by chemical activation. J. Hazard. Mater. 165 (1–3), 1029–1039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.10.133 (2009).

Han, Y., Boateng, A. A., Qi, P. X., Lima, I. M. & Chang, J. Heavy metal and phenol adsorptive properties of biochars from pyrolyzed Switchgrass and Woody biomass in correlation with surface properties. J. Environ. Manage. 118, 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.01.001 (2013).

Feng, J., Qiao, K., Pei, L., Lv, J. & Xie, S. Using activated carbon prepared from typha orientalispresl to remove phenol from aqueous solutions. Ecol. Eng. 84, 209–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2015.09.028 (2015).

Xu, B., Chen, L., Xing, B., Li, Z., Zhang, L., Yi, G., … Mohanty, M. K. Physicochemical properties of Hebi semi-coke from underground coal gasification and its adsorption for phenol. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 107, 147–152. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2017.02.007.

Cheng, W. P., Gao, W., Cui, X., Ma, J. H. & Li, R. F. Phenol adsorption equilibrium and kinetics on zeolite X/activated carbon composite. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 62, 192–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2016.02.004 (2016).

Lingamdinne, L. P. et al. Insights into kinetics, thermodynamics, and mechanisms of chemically activated sunflower stem Biochar for removal of phenol and bisphenol-A from wastewater. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 4267 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through the project number (TU-DSPP-2024-70). The authors also express their sincere gratitude to the Scientific and Technical Research Center on Arid Regions (CRSTRA) for their invaluable support in facilitating this research. Special thanks are extended to the Scientific and Technical Research Center for Physico-Chemical Analyses (CRAPC) branches in Biskra and Laghouat for their assistance in the characterization of activated carbons (ACs), which contributed significantly to the successful completion of this work.

Funding

This research was funded by Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia, Project No. (TU-DSPP-2024-70).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fateh Barbari, Salim Khechana, Lynda Hecini, Naima Bacha, Mohamed Salah Halati, Badereddine Babes: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Investigation, Writing- Original draft preparation. Ahmad Alghamdi, Mohammad Alsharef, Ahmed Althobiti, Badmaw Abebe Gedefie: Data curation, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration, Funding Acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barbari, F., Khechana, S., Hecini, L. et al. Kinetic and isothermal insights on phenol removal via biochar from vicia Faba stems. Sci Rep 15, 40591 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24228-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24228-9