Abstract

The annual increase in total methane emissions in China has decelerated, largely due to the continued implementation of effective emission reduction policies. Tracking methane emission hotspots and characterizing their emission profiles are critical for driving further reductions. However, the specific role of strong methane emissions in the annual trend changes of China’s methane emissions, as well as seasonal emission profiles, has not been clarified. In this study, we use TROPOMI satellite observations to estimate methane emissions in China for 2019-2023 and comprehensively analyze the driving mechanisms of the trend changes and seasonal variations of methane emissions in China by combining the emissions structural properties with the emission regions’ signatures. Our results reveal that methane emission trends in China over the five years, based on top-down estimations, have significantly moderated. Emission intensity has declined, stability has improved, and the geographic distribution exhibits a pronounced north-heavy and south-light pattern. While the proportion of unstable strong emissions has remained small and consistent over the years, their contribution to total emissions remains significant. Moreover, the influence of stable strong emissions and unstable weak emissions on overall methane levels has grown over time. Unstable strong emissions, primarily linked to energy-related activities, play a pivotal role in shaping seasonal methane emission trends in China. These findings highlight the complex interplay of emission sources and provide valuable insights for refining methane reduction strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Methane remains in the atmosphere for a shorter period in comparison with carbon dioxide, however, it exhibits a stronger thermal effect, as measured by the 100-year and 20-year global warming potential, which are about 28 and 82 times that of carbon dioxide, respectively, thus deeper emission reductions of methane would be conducive to controlling the average global warming1. Methane is the second largest greenhouse gas emitted by China, and an increase in methane emissions will jeopardize China’s endeavor to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Methane has been emphasized in national policies and actions to address climate change, and the reduction of methane emissions has been incorporated into national and regional greenhouse gas reduction policies2,3. Opportunities for changes in methane emissions in China have emerged in the near term, influenced by energy, agricultural, and environmental policy drivers4.

The sources of methane in China mainly include energy activities, agricultural activities, and waste treatment5,6,7. Among these, energy activities constitute the largest source, accounting for \(\sim\) 45% of total methane emissions in 2018, with emissions primarily derived from gas escape during coal mining and unorganized emissions in the oil and gas sector8,9,10. Agricultural activities contribute \(\sim\) 40% of methane emissions, which mainly come from digestive emissions of ruminants in the process of animal husbandry and microbial fermentation emissions during paddy rice cultivation in farmland11,12,13. Waste treatment accounts for \(\sim\) 12% of methane emissions, mostly generated from anaerobic decomposition of organic matter in landfills and methane production during sewage treatment14. In addition, there are also methane emissions from natural sources such as biomass combustion and wetlands15.

China has developed a set of regulations on coal mine methane emissions and utilization, which came into full effect in 201016. Methane emissions have shown a regionally dependent response to China’s energy policy of closing small coal mines in the southwest and consolidating large coal mines in the north. Co-production of coalbed methane and coal in southwestern Shanxi has effectively reduced methane emissions due to increased coal production4. China’s energy production layout has changed considerably over the past decade due to policies such as ”eliminating outdated productivity” and ”shifting energy bases to the northwest”17. Meanwhile, the methane emissions have been concentrated in the direction of ”Northeast-Central-Northwest”18. Simultaneously with the changes in the layout of oil and gas resources exploration and development, the distribution of methane escaping emissions in the oil and gas industry shows a general trend of relocation from Northeast and North China to Northwest and Southwest China19. According to previous studies, it was found that the trend of methane growth in coal mines has slowed down significantly and the methane utilization rate has gradually increased17. This change might be attributed to the Chinese coal industry’s policy of addressing overcapacity by closing many high-gas and gas-abrupt coal mines. In addition, improvements in coal mine methane extraction and utilization technology have produced relatively significant impacts.

Due to the large-scale closure of coal mines, methane emissions from abandoned mines are largely underestimated, which leads to an increase in the proportion of abandoned mine methane in China’s total coal methane emissions20. China’s coal carbon emissions will decline steadily under different scenarios due to reduced coal demand during the energy transition21. Estimates of emissions per unit of domestic natural gas production show low life-cycle loss rates, implying a net climate benefit from China’s current ”coal-to-gas” energy transition22. Regionally, Shaanxi, Sichuan and Xinjiang become the main emitting areas, while the main emitting areas switch from the Northeast and North to the Northwest and Southwest. Fluctuations in overall and regional emissions are closely related to the changing landscape of China’s natural gas industry. As methane emissions from China’s natural gas sector increase significantly, methane leakage into the atmosphere could offset the benefits of climate change mitigation23. Methane emissions in the Northeast contributed the most to the growth rate of methane emissions in China, largely attributable to the growth in natural gas use. It is indicated that the increased use of natural gas in China has exerted a detectable impact on atmospheric methane emissions24.

The agricultural sector in China faces the dual challenge of ensuring food security and reducing methane emissions, with heterogeneity and spatial imbalances in the mitigation of methane emissions between provinces. Agricultural and environmental policies for agriculture and for improving crop yields and air quality over the same period have contributed to an increase in crop residues and applications, which may have led to an increase in methane emissions from rice cultivation4. China’s methane emissions slowed down in 2016-2021 compared to the acceleration of global methane emissions over the same period. As a result, China’s contribution to global methane emissions declines significantly25.Based on the specific scenario, it is found that China’s agricultural methane emissions in 2060 will be reduced by about 90% through a combination of technological measures, behavioral changes, and innovative policies26.

Quantitative estimation of methane emissions in China and analysis towards its geographic distribution characteristics are of great significance for controlling greenhouse gas emissions and mitigating the greenhouse effect27,28,29. Based on the bottom-up/top-down approaches, accounting for different emission sectors to develop methane emission inventories and conducting research on the spatial and temporal characteristics of methane emissions and the compositional structure of the emissions are very beneficial for the national level to realize the future methane emission reductions. A previous study conducted a comprehensive comparison of anthropogenic methane emissions in China by synthesizing the most recent and publicly available datasets. The results suggest that spatially different inventories differ significantly in identifying emission hotspots, and that incomplete information on emission patterns may mislead or bias efforts to mitigate CH4 emission reductions. Comparison of the results of existing inventory studies reveals that there is still a large uncertainty in studies on estimating methane fugitive emissions from China’s oil and gas systems due to differences in emission source completeness, accounting methods, and data precision19. At the same time, our estimates are downwardly revised in terms of coal compared to China’s reported emissions to the UNFCCC30. Differences in the spatial and temporal dimensions of the underground mining gas emission factors are also major points of disagreement. Based on these discrepancies, it suggests that we are continuously exploring the possibility of finely engraving methane emission maps for China17,31,32.

According to previous studies, the gradual transformation of methane emissions in China in terms of emission structure, spatial pattern, production composition, and emission intensity has led to the mitigation of the increasing trend of total annual methane emissions. For example, under the policy of coal production capacity reduction in the energy sector, the closure of coal mines in China from 2011 to 2019 has led to adjustments in coal mine methane emission reduction and coal production structure4,20,21,32. The national average emission factor of coal mines decreased from 9 \(m^{3}/t\) in 2011 to 8 \(m^{3}/t\) in 2019, which brought a methane emission reduction benefit of 10.70 Tg33. From 2010 to 2019, energy-related methane emissions shifted geographically. Emissions from coal sources spread northwest, oil emissions shifted southwest, and natural gas emissions concentrated in the southeast, with hotspots in provinces like Shaanxi, Shanxi, Gansu, and Inner Mongolia18. This spatial structural shift in energy distribution could cause a gravitational shift in determinants of drivers and mitigation policies, leading to further improvements in China’s methane emission trends.

Although existing studies have confirmed the slowdown in the growth trend of China’s methane emissions and identified the policy-driven role of key emission sectors such as energy and agriculture, there remain two core research gaps. First, the specific driving mechanisms behind the slowdown in methane emission trends after 2019, particularly the differences in contributions of emission types with varying stability and intensity to interannual changes and seasonal fluctuations, have not been clarified, making it difficult to accurately identify key targets for emission reduction. Second, existing estimations mostly rely on traditional inventories or single data sources, lacking long-term series analysis based on high-resolution satellite observations such as TROPOMI. The accuracy in depicting the dynamic migration of emission spatial patterns such as the shift from Northeast-North China to Northwest-Southwest China is insufficient, which restricts the formulation of region-specific policies. This study, based on 2019-2023 \(XCH_4\) observation data from the TROPOMI satellite and combined with the divergence method to construct an emission estimation model independent of a priori inventories, can not only fill the aforementioned gaps in data and mechanism research but also provide high-credibility quantitative support for analyzing the laws of emission structure transformation and optimizing region-specific and sector-specific methane emission reduction strategies.

Material and methods

Divergence-driven methane emission estimation

The methane estimation model in this study is established based on observations from TROPOMI, driven by the divergence of the horizontal wind field from the ECMWF ERA5 reanalysis. The TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI), on Sentinel-5 Precursor (launched Oct 2017), has provided Level-2 data since May 2018. It enables near-global daily methane observations (overpass 13:30 local time) with high spatial resolution (7\(\times\)7 km² nominal nadir, 5.6 km along-track since Aug 2019) via a spectrometer, surpassing prior methane satellites (e.g., SCIAMACHY, GOSAT)34,35. ERA5 reanalysis data, developed by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), is a global, comprehensive dataset covering 1950 to the near-present (with real-time updates). It boasts high spatial (up to \(0.25^{\circ }\times 0.25^{\circ }\)) and temporal (hourly) resolution, integrating satellite, ground-station, and aircraft observations with advanced models. Offering key variables like temperature, wind, precipitation, and humidity across atmospheric levels, it supports climate research, weather forecast validation, and environmental studies, aiding in understanding climate variability and future projections36.

The algorithmic framework for methane emission estimation used above is based on the divergence approach, which allows obtaining methane emissions at a high spatial resolution without a priori knowledge of the emission sources. Satellite-measured \(XCH_4\) is characterized by abundant emissions from background and regional sources, therefore the contribution from background should be subtracted from the estimation of regional emissions. Orography effects have a large impact on methane transport, so orography effects should be eliminated to reveal the enhancement of emissions on methane transport. The workflow for estimating methane emissions based on TROPOMI \(XCH_4\) consists of three main steps37,38: correction by topography, regional enhancement calculation, and emission estimation based on horizontal wind field divergence. The TROPOMI \(XCH_4\) product was first collected and gridded into a regular latitude/longitude grid of \(0.25^{\circ }\). The \(XCH_4\) data were filtered using a qa value higher than 0.5 for each ground pixel. To eliminate the effect of topography on the intermittent land \(XCH_4\), the relationship between \(XCH_4\) and surface height was corrected by a fitted linear relationship:

where \(XCH_4\) denotes column-averaged dry air mixing ratio of methane, superscripts E and B denote methane enhancement and methane background, respectively, and f(\(XCH_4\), topography) denotes the corrected relationship between \(XCH_4\) and topography, where elevation is used for correction. The regional enhancement is then obtained by eliminating the regional background. The \(XCH_4\)regional background was defined for each grid as described in Ref39.:

where median, mean and std denote the median, mean and standard deviation of the window, respectively. Finally, the enhanced effect of \(XCH_4\) was utilized to calculate spatial divergence40,41 and estimate methane emissions:

Here, the sink term in the flux equation is omitted because the atmospheric lifetime of methane is long enough. Horizontal wind field components were obtained from the ERA5 reanalysis. The divergence was calculated using 100-meter wind data at ground level, with wind field uncertainty minimized by averaging three hours of wind data. To ensure the reliability of the divergence method, wind speeds were constrained to a range of 1 m/s to 10 m/s, as excessively high or low wind speeds can compromise the accuracy of the analysis. Based on the variance of the total monthly methane emissions, the uncertainty of the model’s estimation of total methane emissions is approximately 25%.

Methane emission characterization

We statistically analyzed five years of methane emission data and established an emission magnitude threshold of 5 \(kg \cdot km^2 \cdot h\) to differentiate between strong and weak emissions. Additionally, standard deviations of 3 \(kg \cdot km^2 \cdot h\) and 8 \(kg \cdot km^2 \cdot h\) were used as thresholds to classify emissions as stable or unstable for strong and weak emissions, respectively. This approach enables the classification of emissions into four distinct types. For regional emission characteristics, two classifications were applied. The first is based on the north-south division along the Hu Huanyong line. The second classification considers the emission source type of the city: energy-based provinces such as Shaanxi and Shanxi; energy-based complex provinces like Inner Mongolia; complex cities including Xinjiang and Heilongjiang; and agriculture-based complex provinces such as Jiangxi, Hunan, Hubei, Anhui, Guangxi, Guangdong, and Jiangsu27,28. The methane emission estimation process and emission characterization method are shown in Fig. 1.

Results

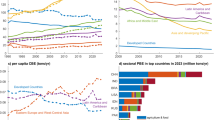

In order to investigate the annual changes in total methane emissions in China, literature reports since 2013 were reviewed. These reports indicate that the anthropogenic methane emissions in China increased from 40 Tg/a to 70 Tg/a from 2000 to 2020, as shown in Fig. 2. This study’s estimate of China’s total annual methane emissions from 2019 to 2023 is depicted with asterisks in Fig. 2(a), showing good comparability with the direction of emission changes reported in the literature from 2015 to 2020. The linear relationships obtained by segmented fitting that was performed in Fig. 2(a) are represented in Fig. 2(b), which shows that the total annual methane emissions exhibit a strong increasing trend in the fitting results for the period until 2019, with a rate of increase in the total annual methane emissions of 1.28 Tg/a. However, a moderation of the trend of growth in the total methane emissions is noticed for the period from 2015 to 2029. The annual methane emissions increasing rate is 0.09 Tg/a. Combined with the estimation results in this paper, a slowing trend in the growth of methane emissions in China from 2015 to 2023 can be identified.

Changes in total methane emissions from China since 2000. (a) Annual variations in total methane emissions. Horizontal lines indicate the range of total emissions over the years. Error bars reflect the uncertainty associated with total emissions. Emissions before 2014 are represented by diamonds, while those after 2014 are shown as circles. The results calculated in this study are denoted by stars. (b) The trends in total methane emissions. Black line illustrates the fitted trend prior to 2019, the red line indicates the trend from 2015 to 2019, and the blue line represents the trend before 2014. Additionally, the functions of the fitting curves, along with the Pearson correlation coefficients and p-values, are provided. Total emissions are marked by black dots.

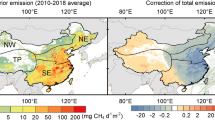

The methane emission map of China obtained after five-year averaging reveals the spatial heterogeneity of the ”northern-dominated emission profile”, as shown in Fig. 3(a). This finding aligns well with previous studies18. Under the regulation of energy-sector emission sources, the pronounced high-intensity methane emissions are particularly evident in regions like Shanxi and Xinjiang. A similar pattern is observed in the geographical distribution of emission standard deviations, as depicted in Fig. 3(b). Upon performing the frequency distribution statistics of methane emission intensity and standard deviation for each year, it is found that the peak of emission intensity occurs in 2020, and the peak of emission standard deviation occurs in 2019. This indicates a trend of decreased intensity and increased stability of methane emissions in China as a whole.

Geographic distributions of mean methane emissions and standard deviation for the five years of 2019-2023 in China. (a) Geographic distribution of mean methane emissions. (b) Geographic distribution of emission standard deviation. The emission maps obtained according to the estimation method are \(0.25^{\circ }\times 0.25^{\circ }\) grids, and those given here are the emission maps after transformed by \(1^{\circ }\times 1^{\circ }\) grids. The transformation method is to transform the size of the emission according to the principle of constant total amount of emissions in a certain area. The circle symbols indicate the mean emission and the square symbols indicate the standard deviation of the emission. The color expresses the magnitude of the value. The size of the circle and square symbols corresponds to the variation in the emissions. The corresponding boxplots of the distribution for each year are shown in the bottom left corner, and the curves are normalized frequency distributions. Frequency distribution uses original resolution data. China’s five-year average total annual methane emission is 60.49 Tg/a. The map was created using basemap 2.0.0 (https://matplotlib.org/basemap/stable/).

Monitoring and emphasizing strong methane emissions is an effective way to increase the efficiency of methane emission mitigation. Here, the geographical distribution of strong emissions with methane emission intensity greater than 5 \(kg \cdot km^2 \cdot h\) is depicted in Fig. 4. The distribution of strong emissions with different stability is respectively given. The standard deviation (STD) threshold for the division of stability is 8 \(kg \cdot km^2 \cdot h\). It becomes clear from the figures that the strong emissions are mainly distributed in the northwestern and northeastern directions29. In the Shanxi region, the northern part tends to be controlled by stable, strong emissions, and the southern part tends to be controlled by unstable strong emissions. In the Xinjiang region, the distribution of strong emissions is wide, with unstable strong emissions occurring in the east and mostly stable strong emissions in the west. The frequency distribution of strong emissions for each year from 2019-2023 shows that the peak of stable, strong emissions occurs in 2023, and the peak of unstable, strong emissions occurs in 2020.

Geographic distribution of strong methane emissions in China. (a) Distribution of stable strong emissions. (b) Distribution of unstable strong emissions. The resolution of the data utilized here is the same as in Fig. 3. The number of corresponding emissions is summarized in each \(1^{\circ }\times 1^{\circ }\) grid and is indicated by colors. The frequency distributions of corresponding methane emissions are shown in the lower left corner. The map was created using basemap 2.0.0 (https://matplotlib.org/basemap/stable/).

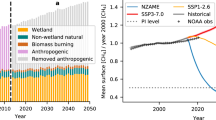

To recognize the driving role of different types of emissions in changing methane emissions in China from 2019-2023, the inter-annual changes of the four types of emissions are given in Fig. 5. Changes in methane emissions in China over the years are given in Fig. 5(a), and it can be noticed that the total methane emissions increase and then decrease over this period. Except for the unstable weak emissions, the other types of emissions are more consistent with the trend of total emissions. Fig. 5(b) presents the quantity proportion of each type of emission in each year, and it shows that the proportion of stable strong emission and stable weak emission decreases with time, and the proportion of unstable weak emission increases with time. Notably, the proportion of unstable strong emissions remains relatively constant, but their intensity decreases over time, as shown in Fig. 5(c). The difference in change between the latter year and the former year is provided in Fig. 5(d-f). From Fig. 5(d), it is clear that the trend of unstable weak emissions is consistent with the trend of total methane emissions. Year by year, the change between 2019-2020 is mainly controlled by the unstable strong emission because the intensity of unstable strong emission changes significantly. The change between 2020-2021 is mainly controlled by the unstable weak emission because the proportion of unstable weak emission changes significantly. The change between 2021-2022 is mainly controlled by the proportion of stable weak emission. The change between 2022-2023 is mainly controlled by a combination of the proportion of stable weak emissions and the intensity of unstable strong emissions. In comprehensive terms, unstable emissions are the main driver of methane emission changes. Stable weak emissions and stable strong emissions gradually transform to unstable weak emissions. Stable strong emissions, while contributing less to total emissions, show an enhancing trend in 2022-2023. Unstable weak emissions, though with smaller emission intensity, gradually increase their proportion and subsequently increase the impact of their contribution to total emissions. The proportion of unstable strong emissions is small and constant, but their contribution to the total emissions cannot be ignored. Therefore, while continuing to concentrate on unstable strong emissions, more attention should be focused on stable strong emissions and unstable weak emissions reduction possibilities.

Changes in China’s annual methane emissions and their main driving factors during 2019-2023. (a) Contribution of the four methane emission types. (b) Quantity proportion of the four methane emission types. (c) The emission intensity distribution of the four methane emission types. (d) Interannual variation in methane emissions. (e) Interannual variation in the proportion of methane emission types. (f) Interannual variation in methane emission intensity.

Few studies have explored the seasonal trends of methane emissions in China.. In this work, the seasonal trend changes of methane emissions in China were analyzedusing remote sensing data from the TROPOMI satellite, as shown in Fig. 6(a). To further explore the driving mechanisms behind these variations, seasonal trends for different regions are presented in Fig. 6(b-g),along with the contributions of the four methane emission types. The regions here are divided into regional and city levels, and the regional level is separated into east and west parts by the Hu Huanyong line. The city level is divided into four types of typical methane-emitting provinces: energy-based, energy-dominated complex, complex, and agriculture-dominated complex. As shown in Fig. 6, the seasonal trend of methane emissions in China closely aligns with the trends observed in the western region of the Hu Huanyong line. The western region has a higher proportion of unstable strong emissions and a lower proportion of stable weak emissions compared to the eastern region. Among the four types of emission provinces, energy-based provinces have consistent seasonal trends of methane emissions with China. Energy-based provinces have the highest proportion of unstable strong emissions and the lowest proportion of stable weak emissions compared to the other three types of provinces. On the contrary, the other agriculture-dominated complex provinces have the lowest proportion of unstable strong emissions and stable strong emissions.

Seasonal variation and drivers of methane emissions in China. (a) Seasonal variation of total methane emissions. (b-c) Seasonal variation of methane emissions in the east and west parts of the Hu Huanyong line. (d-g) Seasonal variation of four types of methane-emitting provinces. (h) Distribution of the four types of methane-emitting provinces. Energy-dominated provinces are represented by Shaanxi and Shanxi. The energy-dominated complex-type province is represented by Inner Mongolia. Complex-type provinces are represented by Xinjiang and Heilongjiang. Agricultural-based complex provinces are represented by Jiangxi, Hunan, Hubei, Anhui, Guangxi, Guangdong, and Jiangsu. The bottom part represents the seasonal variations in the distribution of methane emissions in the corresponding regions. The map was created using basemap 2.0.0 (https://matplotlib.org/basemap/stable/).

Conclusions

In this study, methane emission maps for China from 2019 to 2023 were generated using the divergence method, based on TROPOMI \(XCH_4\) observations without prior information on methane emission sources. The five-year emission trends align well with findings from previous studies, providing insights into total methane emissions, emission structures, spatial distribution changes, and the driving effects of various emission types. These results can support the optimization of methane emission mitigation strategies. Our estimates indicate that China’s total annual methane emissions from 2019 to 2023 ranged from 57.09 Tg (2023) to 64.74 Tg (2022), consistent with reported trends in the literature after 2015. Compared to 2019, total methane emissions decreased by 0.69 Tg in 2023. Over this period, methane emission intensity dropped by 12.26%, and the emission standard deviation decreased by 46.15%. Notably, stable strong emissions increased by 0.51%, while unstable strong emissions declined by 12.5%. The spatial distribution remains dominated by northern emissions, reflecting a ”north-heavy, south-light” scenario.

Among the four types of methane emissions, unstable weak emissions increased by 5.41 Tg, whereas the other types experienced reductions ranging from 0.69 Tg to 3.39 Tg. Although the intensity of unstable strong emissions decreased, the proportion of unstable weak emissions gradually grew. Unstable strong emissions remain a significant driver of methane emission changes, but the increasing role of unstable weak emissions highlights a transition in emission structures. Unstable strong emissions, primarily associated with energy-based activities, significantly influence the seasonal variation of methane emissions in energy-based provinces, shaping the overall seasonal trend in China. However, in other city types, unstable weak and stable weak emissions dominate the seasonal variations. Given the dual dynamics of methane emission shifts toward northern regions and the structural transition to unstable weak emissions, it is crucial to design targeted methane reduction pathways to enhance the long-term effectiveness of mitigation efforts.

Methane emission models based on the divergence method rely heavily on high-precision wind field data and accurate background removal techniques. Despite improvements in wind field averaging and background elimination methods, uncertainties remain, as noted in Ref37.. Future work should focus on incorporating higher-precision wind field data and more robust background removal approaches to further refine these models. The analysis of the cross-impacts among different emission sectors and the long-term dynamic evolution remains insufficient. Additionally, multi-source observational data have not been fully integrated for comprehensive verification, making it difficult to fully cover complex emission scenarios. Future efforts should further optimize from both methodological and data dimensions.

Data availability

The wind product of ECMWF ERA5 can be downloaded at: https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/dataset/ecmwf-reanalysis-v5. S5P TROPOMI methane dataset is available at: http://www.tropomi.eu/data-products/methane.

References

Kikstra, J. S. et al. The ipcc sixth assessment report wgiii climate assessment of mitigation pathways: from emissions to global temperatures. Geoscientific Model Development 15, 9075–9109 (2022).

Zhang, B., Yang, T., Chen, B. & Sun, X. China’s regional ch4 emissions: Characteristics, interregional transfer and mitigation policies. Applied energy 184, 1184–1195 (2016).

Zhang, B. & Chen, G. China’s ch4 and co2 emissions: Bottom-up estimation and comparative analysis. Ecological indicators 47, 112–122 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. Observed changes in china’s methane emissions linked to policy drivers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, e2202742119 (2022).

Guo, F., Dai, F., Gong, P. & Zhou, Y. \(\text{ Chn-ch}_{4}\): a gridded (\(0.1^{\circ }\,\times \,0.1^{\circ }\)) anthropogenic methane emission inventory of china from 1990 to 2020. Earth System Science Data 17, 4799–4819. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-17-4799-2025 (2025).

Gong, S. & Shi, Y. Evaluation of comprehensive monthly-gridded methane emissions from natural and anthropogenic sources in china. Science of the Total Environment 784, 147116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147116 (2021).

Karakurt, I., Aydin, G. & Aydiner, K. Sources and mitigation of methane emissions by sectors: A critical review. Renewable Energy 39, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2011.09.006 (2012).

Sun, S., Ma, L. & Li, Z. A source-level estimation and uncertainty analysis of methane emission in china’s oil and natural gas sector. Energies 15, 3684. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15103684 (2022).

Li, N. et al. Methane emissions from the natural gas industry in china - a systematically accounting based on the bottom-up approach. Gas Science and Engineering 126, 205346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgsce.2024.205346 (2024).

Chen, D. et al. Characteristics of china’s coal mine methane emission sources at national and provincial levels. Environmental Research 259, 119549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.119549 (2024).

Xu, Z., Zheng, Y. & Wu, Y. Paving the way for sustainable agriculture: An analysis of evolution and driving forces of methane emissions reduction in china. Resources Conservation and Recycling 202, 107392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2023.107392 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Mitigation potential of methane emissions in china’s livestock sector can reach one-third by 2030 at low cost. Nature Food 5, 603–614. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01010-0 (2024).

Pan, H. et al. Agriculture related methane emissions embodied in china’s interprovincial trade. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 189, 113850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.113850 (2024).

Du, M. et al. Quantification of methane emissions from municipal solid waste landfills in china during the past decade. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 78, 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.04.082 (2017).

Zhang, X. & Jiang, H. Spatial variations in methane emissions from natural wetlands in china. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 11, 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-013-0385-y (2014).

Miller, S. M. et al. China’s coal mine methane regulations have not curbed growing emissions. Nature Communications 10, 303 (2019).

Zhu, A., Wang, Q., Liu, D. & Zhao, Y. Analysis of the characteristics of ch4 emissions in china’s coal mining industry and research on emission reduction measures. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, 7408 (2022).

Yao, L., Qian, W. & Jiang, H. Spatial-temporal distribution and multiple driving mechanisms of energy-related ch4 emissions in china. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 106, 107463 (2024).

Yang, Z., Gao, J., Tang, X., Zhong, b. & Zhang, b. Accounting and spatial-temporal characteristics of fugitive methaneemissions from the oil and natural gas industry in china, Petroleum. Science Bulletin 3, 1–10 (2016).

Liu, Q., Teng, F., Nielsen, C. P., Zhang, Y. & Wu, L. Large methane mitigation potential through prioritized closure of gas-rich coal mines. Nature Climate Change 14, 1–7 (2024).

Wang, H., Zheng, B., Li, H., Zhang, Q. & He, K. Targeting ultra-emitters for effective methane mitigation in china’s coal sector. ACS ES &T Air 1, 734–742 (2024).

Sheng, J. et al. Sustained methane emissions from china after 2012 despite declining coal production and rice-cultivated area. Environmental Research Letters 16, 104018 (2021).

Li, N. et al. Methane emissions from the natural gas industry in china-a systematically accounting based on the bottom-up approach. Gas Science and Engineering 126, 205346 (2024).

Wang, F. et al. Atmospheric observations suggest methane emissions in north-eastern china growing with natural gas use. Scientific reports 12, 18587 (2022).

Zhao, M. et al. Slow down in china’s methane emission growth. National Science Review 11, nwae223 (2024).

Duan, Y. et al. Agricultural methane emissions in china: inventories, driving forces and mitigation strategies. Environmental Science & Technology 57, 13292–13303 (2023).

Huang, M., Wang, T., Zhao, W., Xie, X. & Wang, D. Estimation of atmospheric methane emissions and its spatial distribution in china during 2015. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae 39, 1371–1380 (2019).

Gong, S. & Shi, Y. Evaluation of comprehensive monthly-gridded methane emissions from natural and anthropogenic sources in china. Science of the Total Environment 784, 147116 (2021).

Lin, X. et al. A comparative study of anthropogenic ch4 emissions over china based on the ensembles of bottom-up inventories. Earth System Science Data 13, 1073–1088 (2021).

Chen, Z. et al. Methane emissions from china: a high-resolution inversion of tropomi satellite observations. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 22, 10809–10826 (2022).

Zhu, T., Bian, W., Zhang, S., Di, P. & Nie, B. An improved approach to estimate methane emissions from coal mining in china. Environmental science & technology 51, 12072–12080 (2017).

Sheng, J., Song, S., Zhang, Y., Prinn, R. G. & Janssens-Maenhout, G. Bottom-up estimates of coal mine methane emissions in china: A gridded inventory, emission factors, and trends. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 6, 473–478 (2019).

Guo, J., Gao, J., Yan, K. & Zhang, B. Unintended mitigation benefits of china’s coal de-capacity policies on methane emissions. Energy Policy 181, 113718 (2023).

MacDonald, C. G. et al. Estimating enhancement ratios of nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide using satellite observations. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 23, 3493–3516. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-3493-2023 (2023).

Veefkind, J. P. et al. Tropomi on the esa sentinel-5 precursor: A gmes mission for global observations of the atmospheric composition for climate, air quality and ozone layer applications. Remote Sensing of Environment 120, 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2011.09.027 (2012).

Deng, X. et al. Comparison of horizontal wind observed by wind profiler radars with era5 reanalysis data in anhui, china. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 150, 1745–1760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-022-04247-6 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. A new divergence method to quantify methane emissions using observations of sentinel-5p tropomi. Geophysical Research Letters 48, e2021GL094151 (2021).

Veefkind, J. et al. Widespread frequent methane emissions from the oil and gas industry in the permian basin. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 128, e2022JD037479 (2023).

Lauvaux, T. et al. Global assessment of oil and gas methane ultra-emitters. Science 375, 557–561 (2022).

Koene, E. F. M., Brunner, D. & Kuhlmann, G. On the theory of the divergence method for quantifying source emissions from satellite observations. Journal of Geophysical Research-atmospheres 129, e2023JD039904. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JD039904 (2024).

Beirle, S. et al. Catalog of nox emissions from point sources as derived from the divergence of the no2 flux for tropomi. Earth System Science Data 13, 2995–3012. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-2995-2021 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72394402; 41921005). Thanks for the support provided by the Space Application System of China Manned Space Program (SCP03-01-04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y.: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing-Original Draft; Writing-Review & Editing, Z.L.: Supervision; Project administration; Funding acquisition, L.S.: Visualization, D.C.: Investigation; Resources, X.D.: Resources; Data Curation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, S., Liu, Z., Sun, L. et al. Structural changes and impacts of methane emissions in China. Sci Rep 15, 40554 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24293-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24293-0