Abstract

Forests store a substantial amount of organic carbon in living biomass and contribute the most to the global terrestrial carbon sink among all vegetation types. Nonetheless, the spatiotemporal variations in and drivers of forest biomass dynamics remain uncertain, especially in regions with strong human disturbances. In this study, we investigated the trends and drivers of forest biomass change in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) from 2000 to 2022 by constructing a remote sensing–based forest biomass model using the forest inventory data in the GBA. Our results indicate the forest biomass model effectively captures (R2 = 0.96) the observed total forest biomass in most cities in the GBA. The total forest biomass in the GBA increased by 18.4% from 2000 to 2022, although the trend and magnitude of changes in forest biomass drastically varied across the GBA. Land use change (LUC) in the GBA induced a slight (– 1%) decrease in forest biomass, while the rise in forest biomass density (FBD) due to tree growth and climate change contributed to a 19% increase in the total forest biomass in the GBA. LUC and FBD explained 17% and 83% of the dynamics of the total forest biomass in the GBA, respectively. Moreover, elevation, slope and temperature is the primary factors controlling the spatial variation in FBD, whereas increase in FBD across GBA over the past two decades was primarily driven by elevated atmospheric CO₂ concentrations. Overall, this study provides an effective framework to quantify forest biomass at a high spatial resolution and decipher the contributions of LUC and FBD changes to forest biomass dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Forests, constituting almost 90% of the terrestrial vegetation biomass1,2, are one of the largest terrestrial carbon sinks1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Accurately quantifying the dynamics of forest biomass is helpful to better assess the terrestrial carbon budget and the response of terrestrial carbon storage to climate change and human disturbances12,13. Therefore, it is necessary to accurately quantify the forest biomass dynamics and the environmental controlling factors that drive these dynamics.

Previous studies that investigated forest biomass changes and their controlling factors were mostly based on site-level inventory data or dynamic vegetation models. Site-level inventories provide detailed biomass data at specific times and locations. However, it is hard to conduct these inventories at a large spatial scale for a long period as they require substantial manpower and resources14. Dynamic vegetation models can effectively simulate changes in forest biomass and its interactions with environmental factors at a large spatial scale15,16,17,18. Nevertheless, these models generally suffer from uncertainties in their simulation results and the substantial demands of computation power when they are run at a fine spatial resolution (e.g., 1 km).

Remote sensing provides an effective way to estimate the dynamics of large-scale forest biomass at high spatial resolutions19,20,21. The integration of satellite imagery (e.g., Landsat) with airborne lidar remote sensing enables the mapping of the forest cover and leaf area index (LAI) at large spatial scales22,23,24,25,26. For example, Zhang and Kondragunta (2006) utilized MODIS land data and leaf-based generalized allometric models to estimate forest biomass components across the contiguous United States23. Zhang (2014) proposed a simple allometric model for estimating live forest aboveground biomass (AGB) using high-resolution LAI data and canopy maximum height data22. Additionally, microwave remote sensing, including measuring the canopy using passive optical sensors or radar backscatter, can enable high-precision AGB mapping (e.g., with a 100-m resolution)27,28,29,30. Meanwhile, existing studies have indicated that the belowground biomass (BGB) can be estimated from the AGB using specific empirical equations31,32,33,34,35. For example, Spawn et al. (2020) estimated the BGB based on the AGB using a rule-based decision model36.

Although many studies have estimated forest biomass using remote sensing data21,27,37,38, clarifying the drivers of the interannual variability in forest biomass remains challenging. The total forest biomass in a region depends on the forest area and the area-averaged forest biomass density39 (FBD). On the one hand, land use change (LUC) can affect the forest area and, hence, the regional total forest biomass; on the other hand, climate, forest age, human disturbances, and many other factors can affect forest biomass by altering the FBD13,40,41,42. Some studies have explored the effects of LUC on forest biomass using the InVEST model. However, the InVEST model generally assumes a fixed FBD across the study area and ignores the spatial and interannual variations in the FBD43.

In this study, an empirical allometric equation for estimating forest biomass based on LAI products and ground-based observations of forest biomass was constructed and used to simulate the forest biomass in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) from 2000 to 2022. Based on the simulated forest biomass, we analyzed the spatial and temporal changes in the forest biomass in the GBA and the drivers of these changes. The specific research goals of this study include: (1) constructing a forest biomass remote sensing estimation model applicable to the GBA, (2) revealing the spatial and temporal characteristics of forest biomass in the GBA over the past 23 years, (3) quantifying the effects of LUC and FBD changes on the total forest biomass in the GBA, and (4) investigating the key environmental controls of the drivers spatiotemporal FBD variations.

Materials and methods

Study area

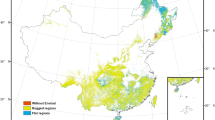

The Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao (GBA) in the south of China (21° 25’–24° 30’ N, 111° 12’– 115° 35’ E) is known as one of the four global major bay areas (Fig. 1) and one of the most economically advanced (contributes 12% of China’s total GDP) regions in China44,45. The GBA is a highly urbanized yet ecologically diverse region, characterized by coastal and estuarine ecosystems, urban ecosystem, croplands and forest. To ensure long-term resilience, the GBA has committed to sustainable and green development, striving to balance rapid economic growth with robust ecological protection. In 2020, the forest area in the GBA was 26,000 km2, accounting for 47% of the GBA’s total area (5.59 × 104 km2)31. The GBA has a subtropical climate with an average annual temperature of 22.3 °C and an average annual total rainfall of 1832 mm yr-1. The entire area is dominated by evergreen broad-leaved forests46. The elevation is high in the northwest of the GBA and low in the southeast, with mountains distributed in the north and plains mainly in the estuary of the Pearl River. Over the past decades, the forest ecosystem in the GBA has experienced notable climate change and human perturbations39,46,47. Accurately quantifying the dynamics of GBA’s forest biomass is essential for revealing its impact on ecological and socio-economic significance12,13.

Locations and distribution of forest and carbon density inventory data in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area. The forest distribution data were obtained from the land use map produced by Yang et al.48. The inventory data on the carbon density at 42 sites were obtained from Xu et al.49. Figure mapping visualizations were performed in ArcGIS Pro (v3.0, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro).

Data

The observed specific leaf area (SLA) data, comprising 4131 records within the GBA, were obtained from the TRY database50,51,52,53,54 (Table 1). The inventory data on the carbon density at 42 sites (kg C m–2) for both AGB and BGB were obtained from Xu et al. (2018)49. The inventory data of the total forest stock volume and forest area data in each district/county of the GBA in 2021 were obtained from the Guangdong Provincial Bureau of Statistics (https://gdzd.stats.gov.cn/, in Chinese). Shenzhen has not publicly released its inventory data on the forest stock volume and forest area. The inventory data on the forest biomass in each district of Shenzhen in 2013 were obtained from Wen et al.55 (Table 1).

The LAI images were obtained from the MOD15A2H.v061 product (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod15a2hv061/). The original LAI data have a temporal resolution of 8 days and a spatial resolution of 500 m. These LAI data have good accuracy across diverse biomes, with a root-mean-square error (RMSE) ranging from 0.66 to 0.6956,57,58,59. We calculated the annual mean LAI images over the GBA using the original 8-day LAI dataset using the Google Earth Engine. The land use data over the GBA at a spatial resolution of 30 m from 2000 to 2022 were extracted from the land use dataset produced by Yang et al.48. The precipitation (Prec) and temperature (Temp) data over the GBA at a spatial resolution of 0.01° were extracted from the ChinaMet dataset produced by Hu et al.60, Zhang et al.61, and Hu et al.62 have indicated that ChinaMet dataset has a good accuracy of Prec in China, with a RMSE ranging from 4 to 12. Data of Atmospheric CO2 concentrations was obtained from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA, https://gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends/). The digital elevation model (DEM) data over the GBA at a spatial resolution of 30 m was extracted from Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM)63. The aspect and slope were derived from DEM using the 3D Analyst tool in ArcGIS Pro. The soil properties, including pH, silt, sand, and clay fractions were obtained from the GSDE dataset produced by Shanguan et al.64.

Calibration of empirical biomass function

The leaf biomass density (LBD) can be calculated from the LAI and SLA using the following equation:

where LAI is the leaf area index, and SLA is the specific leaf area. In this study, the average value (= 163.55 cm2·g-1) of 4131 SLA measurements in the GBA was used in Eq. 1 to calculate the \(LBD\) from the LAI (Fig. 2). To estimate the uncertainties of the simulated LBD, we also estimated the LBD based on an SLA equaling the mean plus standard deviation (SD) of the 4131 SLA measurements (= 93.05 cm2·g-1) and another SLA equaling the mean minus SD of the 4131 SLA measurements (= 234.05 cm2·g-1; Fig. 2).

Many observations have shown that plant growth generally follows an allometric growth relationship22,23,33,36. This provides the possibility and theoretical basis for estimating the AGB and BGB based on leaf biomass. Here we first extracted the LAI data at 42 sites distributed across the GBA49 (Fig. 1) from the MODIS LAI data. Then we calculated the LBD at each of the 42 forest sites from the extracted LAI using Eq. 1. Finally, we trained two empirical allometric functions for calculating the AGB density (AGBD) and BGB density (BGBD) from the LBD respectively using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression in Origin2023 (Fig. 3a, b). Note that, we have conducted a leave-one-out cross-validation to evaluate the accuracy and reliability of the fitted empirical allometric functions, and to access the uncertainties in the optimized parameter values of the fitted empirical functions (Fig. 3c, d). Through leave-one-out cross-validation, we obtained 42 parameters values of the empirical allometric function for AGBD (Eq. 2) and BGBD (Eq. 3), respectively. The means of the 42 fitted parameter values of Eqs. 2 and 3 were finally used to investigate the spatiotemporal variations of forest biomass in GBA. The maximum and minimum of the 42 fitted parameter values were used to quantify the potential uncertainties in our simulated forest biomass.

Relationships between aboveground (a) /belowground (b) forest biomass density and leaf biomass density, and the validations between actual and predicted aboveground(c)/belowground(d) biomass density under leave-one-out cross validation. In subplot (a) and (b), the brown, green and blue lines denote the relationship between leaf and aboveground/belowground forest biomass represented by allometric functions with mean, maximum and minimum of the 42 parameter values obtained from the leave-one-out cross-validation, respectively. RMSE root-mean-square error.

Overall, the LBD explained 78% (RMSE = 1.53) of the observed inter-site variation in the AGBD (Fig. 3a). The empirical function for calculating the BGBD from the LBD is as follows:

The LBD explained 74% (RMSE = 0.53) of the observed inter-site variation in the BGBD (Fig. 3b).

Evaluation of simulated forest biomass

We simulated the forest AGB and BGB in each year from 2000 to 2022 across the GBA based on the MODIS LAI and forest distribution data obtained from 48,56 using Eqs. 1–3 (Table 1). The simulated forest biomass based on the MODIS LAI product was independently validated using the inventory data (Table 1) on the forest biomass in each district and county of the 11 cities in the GBA. The Guangdong Provincial Bureau of Statistics provided the inventory data on the total forest standing stock (m3) and total forest area (hm2) for each district and county of the 11 cities in the GBA. We first calculated the area-averaged density of the forest standing stock (DSD, m3·hm–2) in each city in the GBA with these data. Previous studies32,66 indicated that there is a strong linear relationship between the area-averaged biomass density (DB, t·hm–2) and DSD, although the specific linear regression function describing this relationship depends on the specific forest type. In this study, we collected five empirical linear regression functions from previous studies32,66 to calculate the DB based on the inventory-based DSD. The five regression functions for calculating the DB can be described as follows:

where i is the index of each of the five functions; αi and βi are the slope and interception of each linear regression function. DBi is the Inventory-based biomass calculated by function i. The specific values of αi and βi in each of the five regression functions can be found in Table 2.

The LAI-based total forest biomass calculated based on Eqs. 1–3 in each district and county of the 11 cities in the GBA was evaluated against the average result of the inventory-based biomass obtained from the Guangdong Provincial Bureau of Statistics (Table 1). The evaluation result shows that the LAI-based forest biomass can be compared well with the inventory-based biomass (Fig. 4). The regression slope was close to 1.0 (0.99), and the determination coefficient (R2) of the regression function equaled 0.96.

Drivers of change in forest biomass in GBA during 2000–2022

We further investigated the influences of the FBD (t·hm-2) and LUC on the forest biomass changes across the GBA from 2000 to 2022. Firstly, the actual total forest biomass in the GBA for a specific year was calculated as follows:

where i is a specific year during 2000–2022; Biomassi is the total forest biomass in year i (t); Ai is the forest area in year i (hm2); and FBDi is the FBD in year i (t·hm–2).

We launched a new simulation to investigate the separate effect of the LUC on the forest biomass dynamics in the GBA, in which the forest area Ai changed year by year, while the FBD was fixed to the state in the year 2000:

where Biomassi_LUC is the forest biomass in the year i when there was no change in the FBD across the GBA during 2000–2022 (t). Using the year 2000 as a reference, the change in the total forest biomass (∆Biomassi_LUC, t) due to LUC in year i was calculated as follows:

The change in the total forest biomass (∆Biomassi_FBD, t) due to the FBD in year i was calculated as follows:

The relative contributions of the LUC (RLUC_i, %) and the FBD (RFBD_i, %) to the changes in the total forest biomass in year i were calculated as follows:

Analysis of forest biomass drivers in GBA

We further investigated the key environmental controls of spatial and interannual variations in FBD by partial correlation analysis. Partial correlation analysis is a statistical technique that measures the degree of association between two variables while controlling the influence of one or more additional variables67,68,69. This method is particularly valuable in ecological studies when environmental factors are interrelated70,71. To investigate the key environmental drivers of the interannual variation in FBD, we calculated the partial correlation coefficient between FBD in each city of GBA and the corresponding mean annual atmospheric CO2 concentration, temperature, solar shortwave radiation downward, and annual total precipitation. To explore the key environmental controls of the spatial variation in FBD, we calculated the partial correlation coefficient between mean FBD in each 0.25° × 0.25° km grid cell across the GBA and climatic (mean annual temperature and annual total precipitation), soil (pH and texture), and topographic (elevation, slope, and aspect).

Results

Spatiotemporal variation in LAI in GBA during 2000–2022

The present-day LAI in the GBA showed drastic spatial variations (Fig. 5a). The LAI in the urban regions of the GBA was comparatively lower (< 1.0) than that in areas covered with forests and croplands. The regions with LAI values ranging from one to three were mostly distributed across the entire GBA, accounting for 31.6% of the GBA. LAI values ranging from five to six were primarily distributed in the northwestern, southwestern, and northeastern regions covered with forests. Regions with LAI ranging from three to five acted as transitional zones between urban and forest areas, accounting for 16.9% of the GBA. LAI values of greater than six were primarily distributed in the western and eastern regions of the GBA, covering 7.3% of the GBA.

Spatial distribution of leaf area index (LAI) in 2022 (a) and the change in LAI from 2000 to 2022 (b). Figure mapping visualizations were performed in ArcGIS Pro (v3.0, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro).

The LAI dramatically changed across the GBA from 2000 to 2022 (Fig. 5b). Overall, the LAI in regions neighboring the urban area significantly decreased from 2000 to 2022, particularly in the estuary of the Pearl River. Nevertheless, the LAI in the mountainous regions mostly significantly increased (Fig. 5b). Overall, the average forest LAI in the GBA increased by 16.26% from 2000 to 2022 (Fig. 6a).

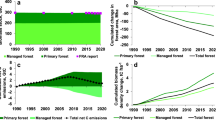

Change trend of forest leaf area index (LAI), area, and biomass during 2000–2022. Change trend of mean forest LAI values across the entire GBA (a). Change trend of forest area in the GBA (b). Annual variations in aboveground and belowground forest biomass (c). The mean aboveground (BIOMabove), belowground (BIOMbelow), and total (BIOMtotal) forest biomass during 2000–2022 (d).

Temporal changes in forest biomass in GBA during 2000–2022

The total forest biomass showed a similar change trend as the LAI during 2000–2022 (Fig. 6a, c). From 2000 to 2005, the forest biomass declined, reaching a minimum in 2005. From 2005 to 2022, the forest biomass in the GBA significantly increased and reached its peak in 2021. The average AGB over the investigated 23 years was 1.02 × 108 t, and the average BGB stood at 0.30 × 108 t (Fig. 6d). The forest biomass increased by 18.24% from 2000 to 2022.

The forest area decreased overall between 2000 and 2003 (Fig. 6b). From 2003 to 2013, the forest area increased every year and reached its maximum in 2013. However, the forest area showed a decreasing trend from 2013 to 2022. Overall, the forest area did not show a significant change trend over the past 23-year period.

In the GBA, Zhaoqing possessed the largest amount of forest biomass (5373.99 ± 589.17, 1 × 104t) compared with the other cities, followed by Huizhou (3529.30 ± 286.76, 1 × 104t), Jiangmen (1665.90 ± 208.53, 1 × 104t), and Guangzhou (1317.53 ± 134.88, 1 × 104t). The forest biomass in the remaining cities overall ranged from 60 to 600 × 104 t. Macao had a minimal amount of forest biomass (0.68 ± 0.095, 1 × 104t).

The forest biomass showed an increasing trend from 2000 to 2022 in most cities of the GBA (Fig. 7). Zhaoqing, Jiangmen, Huizhou, and Guangzhou (Fig. 7a, b) exhibited high biomass levels, except Huizhou, where it remained generally stable. The biomass in other cities showed an increasing trend. Zhaoqing exhibited the most significantly increased biomass in the GBA. Foshan, Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Dongguan (Fig. 7c, e, d) exhibited moderate biomass levels and showed an increasing trend. Zhongshan, Zhuhai, and Macao exhibited low biomass levels, except Macao, where it significantly decreased (Fig. 7f). The biomass in other cities showed an increasing trend.

Change trend of forest biomass in different cities of the GBA from 2000 to 2022. a Interannual changes in biomass in Zhaoqing and Huizhou. b Interannual changes in biomass in Jiangmen and Guangzhou. c Interannual changes in biomass in Shenzhen and Zhuhai. d Interannual changes in biomass in Dongguan and Zhongshan. e Interannual changes in biomass in Hong Kong and Dongguan. f Interannual changes in biomass in Macau. The shadow area in each graph represents the uncertainty of simulated forest biomass, and the solid line represents the mean value of our estimates using Eqs. 2 & 3.

Effects of FBD and LUC on forest biomass change

Our analysis of the respective effects of the LUC and FBD on the total forest biomass in the GBA during 2000–2022 indicated that change in the FBD was the dominant driver of the change in forest biomass in the GBA (Fig. 8). Compared with the reference year 2000, the changes in the total forest biomass in the GBA caused by the FBD dynamics ranged from a decrease of nearly 24 × 106 t to an increase of approximately 35 × 106 t. Meanwhile, the changes caused by the LUC were mostly smaller than 3 × 106 t (Fig. 8a). From 2000 to 2022, the LUC in the GBA induced a slight (– 1%) reduction in the total forest biomass, while the rise in the FBD due to tree growth, climate change, and other factors contributed to a 19% increase in the total forest biomass in the GBA. The relative contribution of the FBD to the interannual variation in the total forest biomass in the GBA was mostly larger than 80% from 2000 to 2022, while that of the LUC was generally smaller than 20%. The LUC and FBD averagely explained 17 ± 17% and 83 ± 17% of the total forest dynamics biomass in the GBA during 2000–2022, respectively (Fig. 8b).

Contributions of changes in forest area and forest biomass density (FBD) to the interannual variation in total forest biomass in the GBA. a Changes in total forest biomass (ΔBIOM) due to FBD (ΔBIOMFBD) and Land use change (LUC) (ΔBIOMLUC). b Relative percentage contributions of changes in forest area and FBD biomass.

The effects of the LUC and FBD on the forest biomass during 2000–2022 strongly varied between cities in the GBA (Fig. 9). The LUC increased the forest biomass in Jiangmen, Zhaoqing, and Shenzhen from 2000 to 2022 yet decreased the forest biomass in Foshan, Zhongshan, Huizhou, Guangzhou, Hong Kong, Zhuhai, and Macao. During 2000–2022, the LUC explained more than 85% of the changes in the forest biomass in Macao, followed by an explanatory power of approximately 35% in Zhuhai and Hong Kong. The LUC explained approximately 20% of the total forest biomass change in Foshan, Dongguan, and Zhongshan, while it explained less than 10% of the total forest biomass change in Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Huizhou, Jiangmen, and Zhaoqing.

Respective effects of changes in forest area and forest biomass density (FBD) on total forest biomass in each city of GBA. a Changes in total forest biomass due to Land use change (LUC) from 2000 to 2022. b Changes in total forest biomass due to FBD from 2000 to 2022. c Relative contribution of LUC to total forest biomass change from 2000 to 2022. d Relative contribution of FBD to total forest biomass change from 2000 to 2022. Figure mapping visualizations were performed in ArcGIS Pro (v3.0, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro).

The FBD increased in all cities in the GBA and caused a rise in the total forest biomass. The changes in the total biomass due to the FBD from 2000 to 2022 in Zhaoqing, Huizhou, Jiangmen, Guangzhou, and Foshan exceeded 142 × 104 t. Meanwhile, the increments in the total forest biomass caused by the changes in the FBD were mostly smaller than 50 × 104 t in Dongguan, Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Zhongshan, Zhuhai, and Macao. Moreover, the changes in the FBD explained approximately 63% of the forest biomass changes in Hong Kong and Zhuhai and more than 90% of the forest biomass changes in Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Huizhou, Jiangmen, and Zhaoqing.

Drivers of the spatial and interannual variations in FBD

Key drivers of the spatial variation in FBD across GBA are quite different from that of the interannual FBD evolutions (Fig. 10).Our result indicate that elevation (represented by DEM), slope, temperature, and precipitation are the primary drivers of the spatial variations in FBD across GBA. Slope and precipitation show a positive correlation, while temperature and DEM show a negative correlation. Aspect solar radiation and soil properties (including pH texture) have no significant (p > 0.05) effect on spatial FBD distribution. Different from the key controls of the spatial FBD variation, interannual FBD variation in GBA was mainly driven by the elevated atmospheric CO₂ concentrations over the past two decades (Fig. 10b). Changes in solar radiation is significantly correlated to FBD only in Jiangmen city. Moreover, we did not find significant relationship between FBD and changes in annual total precipitation and in annual mean temperature (Fig. 10b).

Partial correlation coefficients between forest biomass density (FBD) and its environmental controls. a Partial correlation analysis on the controlling factors of the spatial variation in FBD. b Partial correlation analysis on the interannual variation in FBD. Prec: precipitation. SSRD: surface solar radiation downwards. Temp: mean annual temperature. * represents significant (p < 0.05) partial correlation, and ** represents very significant (p < 0.01) partial correlation.

Discussion

The forest biomass in the GBA showed a recovering and growing trend during 2000–2022, especially during the most recent decade, which might have been driven by improved forest management and elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration (Fig. 7). This increasing trend has also been highlighted in previous studies42,72. In consistent with previous studies 40,73, we found that urbanization played a crucial role in shaping forest biomass dynamics in the transition zones between urban and rural regions,. Cities such as Jiangmen, Zhaoqing, and Shenzhen experienced significant increases in forest biomass, resulting from effective afforestation efforts and elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration. Afforestation policies in these cities have offset some of the negative impacts of urbanization via the rational planning of forest recovery and proper forest management42,73. Conversely, cities such as Guangzhou, Foshan, and Hong Kong experienced more fluctuations in forest biomass, possibly due to high urbanization pressures and unstable afforestation efforts. The high speed of urbanization in these cities has led to large-scale deforestation74,75.

As a major effect on forest biomass change (83%), FBD reflects the integrated responses of forest ecosystems to both long-term climatic forcing and spatial environmental heterogeneity. At the temporal scale, the ‘fertilizing effect’ of atmospheric CO₂ concentration is the primary driver of forest biomass growth in GBA, consistent with the findings of Chen et al. (2024) in a similar study area76. Nonetheless, this fertilization effect may be constrained by nutrient limitations. Thurner et al. (2024) point out that although elevated CO₂ concentrations promote plant growth, this growth may be limited in the absence of sufficient nutrients (such as nitrogen and phosphorus)77. Topographical and climatic factors have a significant impact on the spatial distribution of FBD. Topographical factors such as elevation and slope indirectly influence the spatial distribution of forest biomass by affecting the distribution of water and nutrients78. In addition, climatic factors such as temperature and precipitation also play a key role in regulating the spatial variation of FBD, which is consistent with the findings of Bouchard et al. (2024)79.

Our findings provide valuable insights for future forest management and urban planning in the GBA. As the GBA has made a committed to achieving carbon neutrality in the middle of the 21th century45, urban forests—particularly those in mountainous and suburban areas with high FBD—should be regarded as important natural carbon sink infrastructure. Integrating ecological considerations into urban development planning, along with promoting reforestation and forest conservation, can support the maintenance and enhancement of forest biomass, strengthen urban resilience to climate change, and offer natural solution for achieving the carbon neutrality goal of the GBA. Policymakers are encouraged to prioritize sustainable land management practices to ensure the long-term productivity, stability and ecological function of the forests across the GBA.

Although the empirical allometric forest biomass model developed in this study has been proven to be an effective tool for estimating the total forest biomass in the GBA, we recognize that there are still some potential uncertainties in our results. First, the uneven distribution of the 42 in-situ measurements of the leaf biomass, AGB, and BGB (Table 1) used for training the empirical allometric functions (Eqs. 2, 3) may cause bias in our estimation results, especially in areas without limited sampling coverage. Nonetheless, as these in-situ observation were mainly conducted in the regions with large forest areas, and the measured forests covered both pristine forests and forests in urbanized areas, the 42 forest sites included in this study still have a good representativeness of the forest ecosystems in the GBA. Second, the SLA and the allometric relationships between AGB, BGB, and leaf biomass generally significantly vary between tree species49,54,80. However, as there is still no a database of tree species distribution across the GBA81, we only trained a universal empirical model to represent the allometric growth relationship between AGB, BGB, and leaf biomass, then estimated the uncertainty introduced by the results based on a single value of SLA mean32,55,66.

In addition, potential overestimation of MODIS LAI values has been reported in subtropical regions, which may influence biomass estimates, especially when relying on LAI-derived empirical models82. In this study, we employed the MOD15A2H v061 product, an updated and improved version of the MODIS LAI dataset. Previous studies indicate that this version has been calibrated against ground measurements across diverse biomes, demonstrating improved performance and consistency over earlier releases. Key improvements include reduced LAI saturation effects and minimized bias in dense canopies56,57,83.

In this study, we aimed to explore the spatial and temporal variations in the forest biomass in the GBA over a long time series, as well as its response to LUC and FBD changes. We considered the effects of changes in both forest area and FBD on the total forest biomass across the GBA. Our estimation of the dynamics of forest biomass should thus be more reliable than previous studies39,42,72,73,74,75,84, which considered only the effect of LUC on the regional total forest biomass and ignored the interannual variation in the FBD. Nonetheless, as FBD in GBA can be affected by not only long-term changes in climate, atmospheric CO2 concentration42, but also disturbance events such as typhoon, fires, droughts, and floods6,16,85,86, as well as human-induced disturbances40,41,87. The specific effect of each of these disturbances on forest biomass should be explored in the future to better understand and project the dynamics of forest biomass in the GBA.

Conclusions

This study developed an empirical allometric forest biomass model that can be used to estimate the aboveground and belowground forest biomass using the LAI database. We applied this model to the GBA to investigate the change trend of the forest biomass in the GBA from 2000 to 2022 and the drivers of this change. Our results indicate that the empirical allometric forest biomass model developed in this study is an effective tool for estimating the total forest biomass in the GBA. The FBD across the GBA showed larger spatial variability, with low values in the estuary of the Pearl River and high values in the surrounding mountainous regions. The total forest biomass significantly increased by 18.4% from 2000 to 2022. Nonetheless, the increase in forest biomass mainly occurred in the mountainous regions, while it declined in the transition zone from the urban to the surrounding rural regions. An increase in the FBD due to tree growth, climate change, and many other environmental factors was the main driver (83%) of the increase in total forest biomass across the GBA. LUC played a secondary (17%) role in explaining the dynamics of forest biomass in the GBA. Furthermore, the relative contributions of changes in FBD and land use to the dynamics of total forest dynamics differed between cities. In addition, elevation, slope and temperature is the primary factors controlling the spatial variation in FBD, whereas increase in FBD across GBA over the past two decades was primarily driven by elevated atmospheric CO₂ concentrations. Overall, this study helps us to better understand the spatiotemporal variations in the forest biomass in the GBA, as well as the responses of forest biomass to LUC and climate change. This study also contributes to a better estimate of the carbon sequestration strength of the forests in the GBA.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. Please contact Woheng Li at 1,401,564,074@qq.com.

References

Ma, H. et al. The global distribution and environmental drivers of aboveground versus belowground plant biomass. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1110–1122 (2021).

Pan, Y., Birdsey, R. A., Phillips, O. L. & Jackson, R. B. The structure, distribution, and biomass of the world’s forests. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 44, 593–622 (2013).

Pan, Y. et al. A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science 333, 988–993 (2011).

Pugh, T. A. M. et al. Role of forest regrowth in global carbon sink dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 4382–4387 (2019).

Guerrero-Ramirez, N. R. et al. Diversity-dependent temporal divergence of ecosystem functioning in experimental ecosystems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1639–1642 (2017).

Yang, Y. et al. Terrestrial carbon sinks in China and around the world and their contribution to carbon neutrality. Sci. CHINA-LIFE Sci. 65, 861–895 (2022).

FAO. Global forest resources assessment 2020: Main report. In: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9825en. (2020).

Houghton, R. A. Interactions between land-use change and climate-carbon cycle feedbacks. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 4, 115–127 (2018).

Cheng, K. et al. Carbon storage through China’s planted forest expansion. Nat. Commun. 15, 4106 (2024).

Migliavacca, M. et al. Securing the forest carbon sink for the European Union’s climate ambition. Nature 643, 1203–1213 (2025).

Peng, D. et al. Newly established forests dominated global carbon sequestration change induced by land cover conversions. Nat. Commun. 16, 6570 (2025).

Kim, D. et al. Estimation of future carbon budget with climate change and reforestation scenario in North Korea. Adv. Space Res. 58, 1002–1016 (2016).

Pan, Y. et al. The enduring world forest carbon sink. Nature 631, 563–569 (2024).

Wang, Y., Jia, X., Chai, G., Lei, L. & Zhang, X. Improved estimation of aboveground biomass of regional coniferous forests integrating UAV-LiDAR strip data, Sentinel-1 and sentinel-2 imageries. Plant Methods 19, 65 (2023).

Magalhaes, T. M. Live above- and belowground biomass of a Mozambican evergreen forest: a comparison of estimates based on regression equations and biomass expansion factors. For. Ecosyst. 2, 28 (2015).

Jia, Y., Chang, Y., Ping, X. & Chang, C. Dynamics of carbon stocks of different pools in Huzhong National Nature Reserve, Northeast China under the disturbance of various severity fires. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 32, 2325–2334 (2021).

Ouyang, M. et al. A field-based estimation of moso bamboo forest biomass in China. For. Ecol. Manag. 505, 119885 (2022).

Bergkvist, J. et al. Quantifying the impact of climate change and forest management on Swedish forest ecosystems using the dynamic vegetation model LPJ-GUESS. Earths Future 13, e2024EF004662 (2025).

Chen, Y. et al. Maps with 1 km resolution reveal increases in above- and belowground forest biomass carbon pools in China over the past 20 years. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 897–910 (2023).

Zhou, F. & Zhong, D. Kalman filter method for generating time-series synthetic Landsat images and their uncertainty from Landsat and MODIS observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 239, 111628 (2020).

Lu, D. et al. A survey of remote sensing-based aboveground biomass estimation methods in forest ecosystems. Int. J. Digit. Earth 9, 63–105 (2016).

Zhang, G. et al. Estimation of forest aboveground biomass in California using canopy height and leaf area index estimated from satellite data. Remote Sens. Environ. 151, 44–56 (2014).

Zhang, X. & Kondragunta, S. Estimating forest biomass in the USA using generalized allometric models and MODIS land products. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL025879 (2006).

Min, H. E. et al. Review of forest Leaf Area Index retrieval over rugged terrain based on remotely sensed data. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 26, 2451–2472 (2024).

Zolkos, S. G., Goetz, S. J. & Dubayah, R. A meta-analysis of terrestrial aboveground biomass estimation using lidar remote sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 128, 289–298 (2013).

Xu, L. et al. Changes in global terrestrial live biomass over the 21st century. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe9829 (2021).

Cartus, O., Santoro, M. & Kellndorfer, J. Mapping forest aboveground biomass in the Northeastern United States with ALOS PALSAR dual-polarization L-band. Remote Sens. Environ. 124, 466–478 (2012).

Bouvet, A. et al. An above-ground biomass map of African savannahs and woodlands at 25 m resolution derived from ALOS PALSAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 206, 156–173 (2018).

Antunes, R. et al. Leveraging SAR and optical remote sensing for enhanced biomass estimation in the Amazon with random forest and XGBoost models. ISPRS Ann Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 3, 21–27 (2024).

Chang, Z. et al. Evaluation of optical and microwave-derived vegetation indices for monitoring aboveground biomass over China. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 28(2), 421–436 (2024).

Zeng, Z. Assessment of the Effectiveness of Forest Ecological Restoration in Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macao Greater Bay Area and its Optimization Study (Guangzhou University, 2023). https://doi.org/10.27040/d.cnki.ggzdu.2023.000335.

Yang, K. & Guan, D. S. Forest biomass and its dynamics in Pearl River Delta. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 18(4), 705–712 (2007).

Dong, L., Zhang, L. & Li, F. Evaluation of stand biomass estimation methods for major forest types in the Eastern Da Xing’an Mountains, Northeast China. Forests 10, 715 (2019).

Jin, X. et al. Allometric equations for estimating above- and below-ground biomass of reed (Phragmites australis) marshes. J. Plant Ecol. 18, rtae113 (2025).

Shumie, A. et al. Allometric equations for estimation of above- and below-ground biomass of Acacia mearnsii in northwestern Ethiopia. For. Sci. Technol. 20, 279–285 (2024).

Spawn, S. A., Sullivan, C. C., Lark, T. J. & Gibbs, H. K. Harmonized global maps of above and belowground biomass carbon density in the year 2010. Sci. Data 7, 112 (2020).

Wu, Y. et al. Climate interprets saturation value variations better than soil and topography in estimating oak forest aboveground biomass using Landsat 8 OLI imagery. Remote Sens. 16, 1338 (2024).

Xu, L. et al. Forest aboveground biomass estimation based on spaceborne LiDAR combining machine learning model and geostatistical method. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1428268 (2024).

Tian, L. et al. Dynamic simulation of land use/cover change and assessment of forest ecosystem carbon storage under climate change scenarios in Guangdong Province, China. Remote Sens. 14, 2330 (2022).

Moi, D. A. & Teixeira-de-Mello, F. Cascading impacts of urbanization on multitrophic richness and biomass stock in neotropical streams. Sci. Total Environ. 806, 151398 (2022).

Blarquez, O. et al. Regional paleofire regimes affected by non-uniform climate, vegetation and human drivers. Sci. Rep. 5, 13356 (2015).

Liu, J., Yan, Q. & Zhang, M. Ecosystem carbon storage considering combined environmental and land-use changes in the future and pathways to carbon neutrality in developed regions. Sci. Total Environ. 903, 166204 (2023).

Zheng, H. & Zheng, H. Assessment and prediction of carbon storage based on land use/land cover dynamics in the coastal area of Shandong Province. Ecol. Indic. 153, 110474 (2023).

Yang, Y. & Fan, F. Land surface phenology and its response to climate change in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area during 2001–2020. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110728 (2023).

Chen, R., Ren, C., Liao, C., Huang, Y. & Liu, Z. Spatial dynamics of per capita building carbon emissions in the Greater Bay Area: Pathways to net zero carbon by 2060. Build. Environ. 270, 112501 (2025).

Feng, X., Zeng, Z. & He, M. A 20-year vegetation cover change and its response to climate factors in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area under the background of climate change. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, 1080734 (2023).

Wu, L., Sun, C. & Fan, F. Estimating the characteristic spatiotemporal variation in habitat quality using the InVEST model: A case study from Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Remote Sens. 13, 1008 (2021).

Yang, J. & Huang, X. The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. EARTH Syst. Sci. DATA 13, 3907–3925 (2021).

Xu, L., He, N. & Yu, G. A dataset of carbon density in Chinese terrestrial ecosystems (2010s). China Sci. Data 4, 90–96. https://doi.org/10.11922/sciencedb.603 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. The complexity of trait–environment performance landscapes in a local subtropical forest. New Phytol. 229, 1388–1397 (2021).

Ronghua, L. et al. Are functional traits a good predictor of global change impacts on tree species abundance dynamics in a subtropical forest?. Ecol. Lett. 18, 1181–1189 (2015).

He, P. et al. Leaf mechanical strength and photosynthetic capacity vary independently across 57 subtropical forest species with contrasting light requirements. New Phytol. 223, 607–618 (2019).

Guan, L.-L. & Wen, D.-Z. More nitrogen partition in structural proteins and decreased photosynthetic nitrogen-use efficiency of Pinus massoniana under in situ polluted stress. J. Plant Res. 124, 663–673 (2011).

Kattge, J. et al. TRY plant trait database–enhanced coverage and open access. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 119–188 (2020).

Wen, W., Tan, Y., Shi Zhengjun, S. Z. J. & Peng Yougui, P. Y. G. Biomass and carbon storage and their spatial distribution of economic forest in Shenzhen City. J. West China For. Sci. 44, 90–96 (2015).

Myneni, R. B. et al. Global products of vegetation leaf area and fraction absorbed PAR from year one of MODIS data. Remote Sens. Environ. 83, 214–231 (2002).

Myneni, R., Knyazikhin, Y. & Park, T. MODIS/terra leaf area index/FPAR 8-day L4 global 500m SIN grid V061 NASA EOSDIS land process. Distrib. Act. Arch. Cent. https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MOD15A2H.061 (2021).

Yan, K. et al. A bibliometric visualization review of the MODIS LAI/FPAR products from 1995 to 2020. J. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.34133/2021/7410921 (2021).

Yan, K. et al. Performance stability of the MODIS and VIIRS LAI algorithms inferred from analysis of long time series of products. Remote Sens. Environ. 260, 112438 (2021).

Hu, Y., Zhang, L., Zhao, Y. & Che, T. ChinaMet: A multisource integrated high-resolution multi-variable meteorological dataset for China. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14580706 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Merging multiple satellite-based precipitation products and gauge observations using a novel double machine learning approach. J. Hydrol. 594, 125969 (2021).

Hu, Y. & Zhang, L. Added value of merging techniques in precipitation estimates relative to gauge-interpolation algorithms of varying complexity. J. Hydrol. 645, 132214 (2024).

Farr, T. G. et al. The shuttle radar topography mission. Rev. Geophys. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005RG000183 (2007).

Shangguan, W., Dai, Y., Duan, Q., Liu, B. & Yuan, H. A global soil data set for earth system modeling. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 6, 249–263 (2014).

Hersbach, H et al. ERA5 monthly averaged data on pressure levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.6860a573 (2023).

Guo, Z., Hu, Z., Cai, C. & Liu, P. Stand-Level Models of Biomass and Carbon Stock for Major Forest Types in Guangdong. Sci. Silvae Sin. 37–50 (2023).

Ray-Mukherjee, J. et al. Using commonality analysis in multiple regressions: a tool to decompose regression effects in the face of multicollinearity. Methods Ecol. Evol. 5, 320–328 (2014).

Murray, K. & Conner, M. M. Methods to quantify variable importance: implications for the analysis of noisy ecological data. Ecology 90, 348–355 (2009).

Carr, A., Diener, C., Baliga, N. S. & Gibbons, S. M. Use and abuse of correlation analyses in microbial ecology. ISME J. 13, 2647–2655 (2019).

Moya-Laraño, J. & Corcobado, G. Plotting partial correlation and regression in ecological studies. Web Ecol. 8, 35–46 (2008).

Fieberg, J., Rieger, R. H., Zicus, M. C. & Schildcrout, J. S. Regression modelling of correlated data in ecology: subject-specific and population averaged response patterns. J. Appl. Ecol. 46, 1018–1025 (2009).

Zhou, R., Lin, M., Gong, J. & Wu, Z. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity and influencing mechanism of ecosystem services in the Pearl River Delta from the perspective of LUCC. J. Geogr. Sci. 29, 831–845 (2019).

Li, T., Li, M.-Y. & Tian, L. Dynamics of carbon storage and its drivers in Guangdong Province from 1979 to 2012. Forests 12, 1482 (2021).

Chen, L. & Ma, Y. Exploring the spatial and temporal changes of carbon storage in different development scenarios in Foshan, China. Forests 13, 2177 (2022).

Zhu, Z., Ma, X. & Hu, H. Spatio-temporal evolution and prediction of ecosystem carbon stocks in Guangzhou City by coupling FLUS-InVEST models. Soil Water Conserv 41, 222-229,239 (2021).

Chen, T. et al. Elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration and vegetation structural changes contributed to gross primary productivity increase more than climate and forest cover changes in subtropical forests of China. Biogeosciences 21, 2253–2272 (2024).

Thurner, M. A., Caldararu, S., Engel, J., Rammig, A. & Zaehle, S. Modelled forest ecosystem carbon–nitrogen dynamics with integrated mycorrhizal processes under elevated CO2. Biogeosciences 21, 1391–1410 (2024).

Fang, Y. et al. Modeling the topographic influence on aboveground biomass using a coupled model of hillslope hydrology and ecosystem dynamics. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 7879–7901 (2022).

Bouchard, E. et al. Global patterns and environmental drivers of forest functional composition. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 33, 303–324 (2024).

McRoberts, R. E., Chen, Q., Walters, B. F. & Kaisershot, D. J. The effects of global positioning system receiver accuracy on airborne laser scanning-assisted estimates of aboveground biomass. Remote Sens. Environ. 207, 42–49 (2018).

Goudie, J. W., Parish, R. & Antos, J. A. Foliage biomass and specific leaf area equations at the branch, annual shoot and whole-tree levels for lodgepole pine and white spruce in British Columbia. For. Ecol. Manag. 361, 286–297 (2016).

Pandya, S., Yang, Y., Jones, D. L., Engel, J. & Liu, C. Multisensor processing algorithms for underwater dipole localization and tracking using MEMS artificial lateral-line sensors. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2006, 1–8 (2006).

Yan, K. et al. Evaluation of MODIS LAI/FPAR product collection 6: part 2—validation and intercomparison. Remote Sens. 8, 460 (2016).

Wang, G., Guan, D., Xiao, L. & Peart, M. R. Forest biomass-carbon variation affected by the climatic and topographic factors in Pearl River Delta, South China. J. Environ. Manag. 232, 781–788 (2019).

Bacanamwo, M. & Purcell, L. C. Soybean dry matter and N accumulation responses to flooding stress, N sources and hypoxia. J. Exp. Bot. 50, 689–696 (1999).

Reinhart, K. O., Dangi, S. R. & Vermeire, L. T. The effect of fire intensity, nutrients, soil microbes, and spatial distance on grassland productivity. PLANT SOIL 409, 203–216 (2016).

Loarie, S. R., Asner, G. P. & Field, C. B. Boosted carbon emissions from Amazon deforestation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L14810 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Basic and Applied Foundation Projects (SL2023A04J00997) provided by the Science and Technology Bureau of Guangzhou, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Sun Yat-sen University (No. 31610004), and Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2020A1515110423).

Funding

This study was supported by the Basic and Applied Foundation Projects (SL2023A04J00997) provided by the Science and Technology Bureau of Guangzhou , the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Sun Yat-sen University (No. 31610004), and Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2020A1515110423)China Meteorological Administration Eco-Environment and Meteorology for The Qinling Mountains and Loess Plateau Key Laboratory (2024Y-15), and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (2023B1212060019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HZ and KX designed this study. WL performed the specific data and result analysis, with help from HZ, JX and KX. WL wrote the manuscript, with substantial contributions from all co-authors. HZ, JX and KX contribute to the visualization and interpretation of the simulation results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Xiang, K., Xie, J. et al. Trend and drivers of forest biomass change in the Greater Bay Area of China from 2000 to 2022. Sci Rep 15, 40638 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24345-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24345-5