Abstract

This research reports a novel magnetized polyacrylonitrile-modified chitosan (CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4) nanomaterial, as a heterogeneous catalyst, for multicomponent reactions (MCRs). Appropriate characterization using techniques such as Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, and field emission scanning electron microscopy, as well as N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, and vibrating sample magnetometer techniques confirmed the successful synthesis and structure of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite. This multifunctional catalyst combines basic and Lewis acidic active sites, enhancing its catalytic performance. The catalytic ability of CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanomaterial was demonstrated in MCRs for the synthesis of biologically active dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole (DHPPs) and 2-amino-3-cyano-4H-pyran derivatives. These reactions afforded excellent yields of the desired products with a simplified work-up process. Additionally, the catalyst exhibited almost facile recyclability, as well as maintaining its activity for at least five consecutive runs in both MCRs without a considerable decrease in its catalytic activity. This work highlights the development of a sustainable and efficient magnetic nanocatalyst for the synthesis of valuable heterocyclic compounds. Its simple recovery and reusability offer significant advantages over traditional catalysts, making it a promising candidate to address green chemistry principles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heterogeneous catalysts have become pivotal in the pursuit of cost-effective and eco-friendly organic synthesis1,2,– 3. Their reusability offers a significant advantage over homogeneous catalysts4,5. The desirable properties of heterogeneous catalysts address many green chemistry principles, making them a preferred choice for organic synthesis6,7. Their recovery and separation simplicity, reduced corrosion issues, and environmental friendliness have driven substantial research and development in this area8,9,10,11,12.

Nanoparticles (NPs), with their exceptional physicochemical properties including high surface area-to-volume ratio, mechanical and thermal stability, thermal and electrical conductivity, and corrosion resistance, have shown great potential as efficient catalysts13,14. Owing to their high surface-to-volume ratio, NPs can catalyze chemical reactions at a much faster rate than conventional catalysts. However, their small size often hinders their recovery from reaction mixtures, limiting their practical applications15. Magnetic catalysts align well with green and sustainable chemistry principles for organic synthesis16,17,18,19,20. Their ability to accommodate active catalytic centers or organic functional groups on magnetic materials such as Fe3O43,17,21,22, CoFe2O423, CuFe2O424, and NiFe2O425 has garnered interest due to synergistic effects, heat induction, and efficient magnetic separation 26. To date, a broad spectrum of catalytic systems, encompassing both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts, has been explored, including Pd NPs@Fe3O4/chitosan/pumice hybrid beads3, Fe3O4@CS/DAR-Au22, Fe3O4@CS-Ni27, Fe3O4/GO@melamine-ZnO28, Fe3O4@SiO2-Schiff base-Cu(II)29, MNPs-SA@Cu MOF30, Fe3O4@SiO2@APIDSO3H31. Among magnetic materials, Fe3O4 NPs exhibit superior magnetization but are more reactive in acidic environments, leading to faster magnetic property loss32.

Biopolymers, being one of the most widely used heterogeneous catalysts, have attracted considerable attention3,33,34,35. Chitosan, a natural polymer renowned for its biocompatibility and biodegradability, has emerged as an attractive material for the synthesis of MNPs36,37. Its chemical and physical properties facilitate the creation of MNPs that can serve as drug carriers or in water and wastewater treatment38,39.

Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) or polyvinyl cyanide is a linear polymer characterized by a high melting point and notable properties, including thermal resistance, mechanical robustness, electrochemical stability, solubility in polar solvents, and resistance to oxidative degradation. The presence of a significant number of nitrile (C≡N) functional groups along the polymer backbone renders PAN amenable to chemical modification with various materials. This susceptibility to modification is facilitated by several reaction types, such as nucleophilic addition, 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions, and hydrolysis40. The combination of chitosan and polyacrylonitrile can lead to magnetic nanoparticles with enhanced properties. The incorporation of both chitosan and Fe₃O₄ into the structure of magnetic Cs-g-PAN not only reduces the toxicity of the final composite significantly but also allows for better control over the size and distribution of the nanoparticles41.

Multicomponent reactions (MCRs) are significant methods to synthesize diverse complex heterocyclic compounds42,43. They have received great attention because of striking advantages including simplicity, cost-effectiveness, atomic economy, energy and time savings, mild reaction conditions, and high selectivity44. In the mid-20th century, when chemists began to explore the synthesis and properties of heterocyclic compounds, the first reports of dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazoles (DHPPs) were initially synthesized via a process involving tetracyanoethylene and 3-methyl-1-phenylpyrazolin-5-one, which was published in the 1960s and 1970s, mainly focusing on their synthesis via MCRs and cycloadditions37. These early studies established the foundation for understanding the basic structural and chemical properties of these compounds45.

DHPPs are essential heterocyclic scaffolds found in many biologically-active molecules. The core structure of dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazoles consists of a six-membered pyran ring fused to a five-membered pyrazole ring. This fusion results in a rigid, planar structure that provides a stable framework for the attachment of substituents at different positions46. The presence of both oxygen and nitrogen atoms in the heterocyclic system imparts polarity and reactivity, which are crucial for their biological interactions47,48. They possess pharmacological significance as antimicrobials, anticancers, anti-inflammatories, muscle relaxants, and p38 MAP Kinase and CHK1 kinase inhibitors49,50. While numerous catalysts have been developed for their synthesis, many of these protocols suffer from limitations such as lengthy reaction times, complex work-up procedures, and environmental concerns51,52. Typical examples including ionic liquids, L-proline, PEG, melamine-modified chitosan53, and magnetic silica functionalized with 3,4-diaminobenzoic acid54, have been employed for the synthesis of oxygen-containing DHPPs heterocycles55. Hence, the study of DHPPs has received significant interest in terms of exploring their biological properties as well as developing more efficient protocols for their environmentally-benign synthesis56.

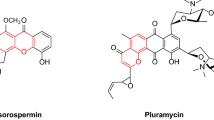

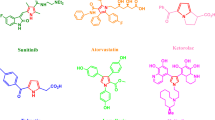

As fundamental components of this field, DHPP as well as 4H-pyran compounds have been the subject of considerable research, with preliminary advances already made. Nevertheless, further development and refinement of their synthetic methodologies are warranted, necessitating ongoing investigation57. The significance of DHPP and 4H-pyran heterocyclic compounds is unambiguous, as they comprise a vital and indispensable realm within the broader discipline of chemistry. A range of pharmaceutical compounds and their therapeutic applications are exemplified in Fig. 1A-H. 4H-pyran derivatives exhibit various medicinal properties such as antispasmodic, anticoagulant, antiallergic, antimicrobial, antidepressant, antifungal, hypoglycemic, anti-HIV, and antipyretic activities58,59,60, and also a therapeutic activity for neurological diseases including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s,40. Therefore, different methods and catalysts have been reported for the synthesis of this oxygen-containing heterocycles such as ionic liquids61,62, sodium alginate63, chitosan-EDTA-cellulose63, Fe3O4@Hal-Glu-EPI-SO3H IL64, Na2CaP2O765, potassium phthalimide-N-oxyl in water under reflux conditions66, potassium phthalimide under ball milling67. However, there are some challenges with the protocols developed for the synthesis of both dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole and 4H-pyran derivatives including moderate yields, long reaction times, the use of toxic reagents with high reactivity, such as ClSO3H for the preparation of catalytic systems, and difficulties in their recycling and reusability.

To address these challenges and in the continuation of our research, we have developed a magnetized PAN-modified chitosan (CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4) nanomaterial (Fig. 2)67,68,69. The magnetic nature of the catalyst enables its easy recovery and reuse, making it a sustainable and efficient heterogeneous catalyst for the one-pot condensation reaction involving β-dicarbonyl compounds, hydrazine hydrate, and active methylene compounds including malononitrile has been employed as a simple and efficient method for the synthesis of dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole (DHPP) (Fig. 3a) and 4H-pyran derivatives (Fig. 3b).

Experimental

General information

The high-purity chemicals were purchased from Merck and Sigma Aldrich companies. The solvents used in the experiments consisted of high-purity distilled water and 96% EtOH. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analyses were performed using a UV lamp with a wavelength output of 254 nm. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra were recorded using KBr pellets on a 1720-X Perkin Elmer (USA) spectrometer. Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDS) spectra and X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained using Bruker EDS (Germany) and D8 ADVANCE diffractometer (Germany) with Cu Ka radiation (λ = 1.54050 Å) instruments, respectively. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the samples was measured using a STA 300 Hitachi device. Field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) images were obtained using a FESEM-ZEISS (Germany) and TESCAN-MIRAII instrument. The magnetic behavior of samples was measured using a Meghnatis Daneshpajooh Kashan, Iran vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM). A Micromeritics ASAP 2020 (USA) instrument was used to conduct the BET and BJH tests. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (¹H NMR) spectra were obtained at room temperature using a Bruker Avance 500 spectrometer with deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) as the solvent. Melting point determinations were carried out using a 9100 Electrothermal apparatus, and the values are reported without correction. Product yields were determined based on the isolated and purified compounds.

Preparation of the CS-g-PAN nanomaterial

A solution of chitosan (CS, 1.0 g) was prepared in 100.0 mL of a 5–10% aqueous acetic acid (AcOH) solution by heating at 50 °C with continuous stirring until a clear and colorless solution was formed. This solution was subsequently degassed under N2 atmosphere for a minimum of 15 min. An aqueous solution of ammonium persulfate (APS, 1.0 mmol dissolved in 50.0 mL of water) was then added dropwise over a 30-minute period. After maintaining the reaction mixture at 55 °C for 45 min, acrylonitrile (AN, 90 mmol, 6.0 mL, d = 0.81 g/mol) was gradually introduced, and the mixture was allowed to react for a further 40 min. The polymerization process was allowed to proceed for 15 h, after which the mixture was treated with EtOH (96%, 200.0 mL) to induce the formation of the CS-g-PAN nanocomposite hydrogel. Following a 4 h period, the resulting hydrogel was collected and subjected to repeated washing cycles with EtOH and deionized water. Finally, the purified hydrogel was dried in an oven at 50 °C for 1 h.

Preparation of the magnetic decorated polyacrylonitrile-grafted chitosan (CS-g-PAN MNPs) nanocomposite

The CS-g-PAN nanomaterial was further modified by introducing magnetic nanoparticles to its composition via an in-situ coprecipitation technique. Initially, 0.54 g (1.0 mmol) of ferrous chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl2.4H2O) and 0.92 g (2.0 mmol) of ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3.6H2O) were dissolved in 20 mL of distilled water and agitated at ambient temperature for 20 min. Subsequently, 0.66 g of the CS-g-PAN nanocomposite was introduced into the aforementioned solution and stirred under a N2 atmosphere for an additional 20 min. Upon raising the reaction temperature to 80 °C, 10 mL of a 28% liquid ammonia solution was gradually added to the reaction mixture over 20 min. The reaction was then allowed to proceed for approximately one hour. The resulting precipitate was magnetically separated and subsequently subjected to multiple washes using distilled water, EtOH, and acetone to eliminate any residual unreacted components. Finally, the obtained magnetic nanocomposite was dried in an oven at 70 °C for a duration of 2 h.

General procedure for the synthesis of DHPP 6a-p derivatives in the presence of CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocatalyst

The synthesis was conducted at 80 °C by incorporating 10.0 mg of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 catalyst (1) into a 2.0 mL solution of EtOH and water (EtOH/H2O, 1:1 v/v) containing the following reactants: Ethyl acetoacetate (2, 1.0 mmol), hydrazine hydrate (3, 1.2 mmol), an aromatic aldehyde (5, 1.0 mmol), and malononitrile (4, 1.0 mmol). Reaction progress was monitored using thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Upon completion, the reaction mixture was dissolved in hot EtOH, and the undissolved magnetic catalyst was subsequently separated using an external magnet and filtration. The obtained crude product was then purified via recrystallization from EtOH to yield the desired DHPP 6a-p derivatives (Fig. 2a).

General procedure for the synthesis of 2-amino-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile 8a-j derivatives in the presence of CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocatalyst

A mixture consisting of an aromatic aldehyde (5a, 1.0 mmol), malononitrile (4, 1.0 mmol), dimedone (7, 1.0 mmol), and CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 catalyst (1, 0.01 g) was stirred in 2.0 mL of EtOH at room temperature. The reaction’s progress was tracked using thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Upon completion, additional hot EtOH was introduced to the mixture to dissolve the product, allowing for the separation of the undissolved nanocatalyst by using an external magnet and filtration. The crude products were then purified through recrystallization in EtOH, yielding 2-amino-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile 8a-j derivatives. The structural identification of these derivatives was confirmed by measuring of their melting points, and in certain instances, by obtaining of their FTIR and 1H NMR spectral data.

Spectral data of the selected products

6-Amino-4-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-methyl-2,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c] pyrazole-5-carbonitrile (6a)

1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) = 1.80 (s, 3 H, ), 4.64 (s, 1H), 6.91 (s, 2H), 7.20–7.22 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H, Harom.), 7.38–7.40 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H, Harom.), 12.15 (s, 1H, NH).

6-Amino-4-(4-methylphenyl)-3-methyl-1,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole-5-carbonitrile (6d)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) = 1.80 (s, 3H), 2.25 (s, 3 H), 4.65 (s, 1H), 6.94 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.20–7.22 (d, 2H, J = 10.0 Hz, Harom.), 7.38–7.40 (d, 2H, J = 10.0 Hz, Harom.), 12.15 (s, 1H, NH).

6-Amino-3-methyl-4-(3-nitrophenyl)-1,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole-5-carbonitrile (6k)

1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) = 1.82 (s, 3H), 4.89 (s, 1H), 7.07 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.63–7.68 (m, 2H, Harom.), 8.03 (s, 1H, Harom.), 8.13–8.15 (dd, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, Harom.), 12.22 (s, 1H, NH).

2-Amino-4-(4-chlorophenyl)-7,7-dimethyl-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-arbonitrile (8a)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) = 0.94 (s, 3H), 1.03 (s, 3H) 2.09–2.26 (ABq, J = 16.0 Hz, 2H), 2.50 (s, 2H) 4.19 (s, 1H), 7.07 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.16–7.36 (m, 4 H, Harom.).

2-Amino-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-7,7-dimethyl-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile (8d)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) = 0.94 (s, 3H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 2.09–2.26 (ABq, J = 16.0 Hz, 2H), 2.51 (s, 2H), 4.19 (s, 1H), 6.54–6.99 (m, 6 H, 4Harom. and 2H of NH2), 9.29 (s, 1H, OH).

2-Amino-4-(3-nitrophenyl)-7,7-dimethyl-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile (8h)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) = 0.93 (s, 3H), 1.02 (s, 3H), 2.10–2.27, (ABq, J = 16.0 Hz, 2H), 2.51 (s, 2H), 4.56 (s, 1H), 7.19 (s, 2H, NH2) 7.59–8.09 (m, 4 H, Harom.).

2-Amino-7,7-dimethyl-4-(2-nitrophenyl)-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile (8i)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) = 7.82 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Harom.), 7.67 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Harom.), 7.43 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Harom.), 7.36 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Harom.), 7.22 (s, 2H, NH2), 4.93 (S, 1H), 2.44–2.56 (ABq, J = 20.2 Hz, 2H), 2.00-2.22 (Abq, J = 16.2 Hz, 2H), 1.01 (s, 3H), 0.88 (s, 3H).

2-Amino-4-(4-cyanophenyl)-6,6-dimethyl-7-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile (8j)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) = 7.77 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H, Harom.), 7.36 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, Harom.) 7.15 (s, 2H), 4.29 (s, 1H), 2.53 (s, 2H), 2.25 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 2.11 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 0.95 (s, 3H).

Results and discussion

Characterization of the magnetic decorated polyacrylonitrile-grafted chitosan with ferrite nanoparticles (CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite)

Characterization of nanoparticles typically involves various techniques to understand their size, shape, composition, surface properties, and other relevant characteristics. To confirm the structure and surface characteristics of the prepared magnetic CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite, several analyses were employed. These analyses include Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) for identifying functional groups through vibrational modes, field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) for detailed imaging to reveal information about size and morphology, X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) for determining the crystallinity degree of structure and providing insights into composition and arrangement, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) for determining the elemental composition of the nanoparticles, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) for assessing specific surface area and porosity, and vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) technique for measuring magnetic properties including magnetic moment, magnetic susceptibility, and coercivity.

Fourier‑transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite

To determine the functional groups and structure of PAN (a), chitosan (b), CS-g-PAN (c), and CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 (d) as well as the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 catalyst (1), FTIR spectroscopy was employed. The results are exhibited in Fig. 4. The broad band at 3435 cm− 1 can be assigned to O‒H and N‒H stretching vibrations. The stretching vibration band of C‒H was observed at 2960 cm− 1, while the bands in the region of 2194–2251 cm− 1 can be considered for the corresponding C≡N functional group. On the other hand, the band observed at 1655 cm− 1 can be attributed to the C = O bond of the amide group in the chitosan moiety. Furthermore, out of plane and in plane bending vibrations of CH2 units appeared at 1460 and 1390 cm− 1, respectively. The C–O stretching bands are located at about 1100 cm− 170. In FTIR, the nanocomposite Cs-g-PAN/Fe3O4 had a new characteristic absorption band at about 580 cm− 1, which is related to the stretching vibration of Fe–O and confirms the presence of Fe3O4 MNPs in the nanocomposite structure. All of these data demonstrate successful grafting of PAN to the backbone of chitosan biopolymer and subsequent formation of its magnetic nanocomposite.

Field Emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite

The morphological features and dimensions of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocatalyst were investigated using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) analysis, as depicted in Fig. 5. The acquired FESEM images revealed that the nanocatalyst particles predominantly exhibit a spherical shape with non-smooth surfaces, which effectively enhances their surface area and catalytic activity. The FESEM micrographs of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 catalyst demonstrated a uniform distribution of MNPs throughout the sample. Notably, the formation of a porous structure was observed, which can be attributed to the grafting of polyacrylonitrile (PAN) onto the chitosan (CS) backbone and the subsequent incorporation of Fe3O4 NPs71, 72. This porous design offers highly advantageous features as it facilitates the accessibility of reactants to the catalytically active sites, thereby improving the overall catalytic performance of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocatalyst.

Powder X‑ray diffraction (XRD) of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite

X-Ray diffraction (XRD) analysis is a non-destructive method that provides detailed insights into the crystallographic structure, physical properties, and chemical composition of materials73. The XRD spectra of chitosan (CS) and its graft copolymer (CS-g-PAN) are presented in Fig. S6. The intense peak observed in the CS spectrum at approximately 2θ = 19.20° is attributed to the overlapping diffraction from the crystal planes (020) and (110) of chitosan. In contrast, the more intense peak in the CS-g-PAN spectrum at approximately 2θ = 16.75° is ascribed to the overlapping diffraction peaks from the crystal planes (110) and (200) of polyacrylonitrile (PAN)74. Notably, the diffraction intensity of the peak at around 2θ = 20.00° in the CS-g-PAN spectrum is significantly weakened, indicating a decrease in the crystallinity of chitosan after modification. This suggests that PAN has grown into sufficiently long chains to form regular crystalline regions during the grafting copolymerization process. Furthermore, the XRD spectrum of CS-g-PAN reveals reflection peaks at 2θ = 18.00°, 30.21°, 35.91°, 37.59°, 43.28°, 53.68°, 57.16°, and 62.82°, which are assigned to the characteristic peaks of cubic Fe3O475. Additionally, a relatively broad diffraction peak is observed at 16.99°, corresponding to the (100) crystal plane structure of PAN. The compatibility between the components is further supported by the fact that all peaks in the composite pattern match well with the desired pattern of each component, indicating that there are no significant interferences or disruptions in the crystal structure of the composite material due to blending. This suggests a high degree of compatibility and structural integrity in the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 composite (Fig. S6).

EDS and mapping elemental analysis of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite

The identification of N, Fe, and O elements through energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis provides further justification for the successful synthesis of CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocatalyst (Fig. 6a). Furthermore, the EDS elemental mapping analysis of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 catalyst, as depicted in Fig. 6b, clearly confirms the presence of Fe, N, and O elements within the nanomaterial’s composition. Notably, the mapping analysis reveals a uniform distribution of these desired elements in the structure of nanocomposite 1.

Vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) analysis of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite

Figure 7 illustrates the magnetization curve of magnetic CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanomaterial, providing a detailed characterization of their magnetic behavior. A distinct ferromagnetic response is observed in the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite, with a saturation magnetization value of 15.1 emu/g. This behavior is consistent with the previous reports on Fe3O4-containing nanocomposites, especially when the average particle diameter is below 17 nm. The observed MNPs are therefore reliable , contributing to their ability to respond to an external magnetic feild, particularly within the context of CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanomaterial.

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area analysis and Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) pore size analysis of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite

The N2 adsorption-desorption porosimetry technique was utilized to determine various quantitative aspects of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanomaterial’s porous nature, including surface area, pore diameter, and total pore volume. The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm and BJH pore volume of the catalyst are illustrated in Fig. S9, respectively. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area of the catalyst was approximately 59.60 m².g-1, indicating a relatively high surface area compared to the pristine chitosan76. The average pore width sizes were calculated using different methods, yielding values of 100.28 Å using the 4V/A by BET method, 104.94 Å using the BJH adsorption method, and 108.60 Å using the BJH desorption method. These results suggest that the MNPs have contributed to the formation of a suitable surface area, highlighting the potential of this nanomaterial for various applications.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanomaterial

TGA is a widely used method for analyzing the thermal behavior of materials and identifying the stages of degradation or mass changes that occur due to temperature rising. The first main mass loss is observed at 66 °C, which is usually attributed to the loss of moisture or volatile solvents such as water or EtOH. Chitosan is hydrophilic due to the presence of amine and hydroxyl functional groups and can retain water in its structure through surface adsorption or hydrogen bonding. The weight loss at 289 °C is related to the initial degradation of the chitosan polymer as well as PAN chains. At this stage, glycosidic bonds in the chitosan structure break, and side groups, such as cyanide groups in the PAN, may begin to decompose. Indeed, the presence of PAN increases the degradation temperature compared to pure chitosan. The breakdown at 418 °C is related to a more complete degradation of the polymer structure and the decomposition of the main chains of chitosan and PAN. The temperature of 626 °C is related to the final destruction of organic and inorganic structures. At this stage, the organic parts of the material are completely decomposed and inorganic residues remain (Fig. S10).

Systematic investigation of the optimized conditions for the synthesis of DHPP and 4H-pyran derivatives

To study the synthesis of DHPP derivatives in the presence of CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocatalyst, a model reaction comprising of benzaldehyde (5a), ethyl acetoacetate (2a), hydrazine hydrate (3), and malononitrile (4) was chosen. Various influencing parameters, including catalyst and solvent type, catalyst loading, and temperature, were systematically studied. The results of these experiments have been summarized in Table 1. The obtained yield of the desired DHPP, 6-amino-4-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-methyl-2,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c] pyrazole-5-carbonitrile (6a), was not significant when the model reaction was run in the absence of any catalyst under solvent-free conditions at room temperature or 80 oC (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). Subsequently, the model reaction was also carried out in the acetonitrile solvent, which also did not afford a significant yield of the desired product 6a (entry 3). When the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 catalyst was added to the model reaction under solvent-free conditions, the yield increased to approximately 50%. This enhancement is rationalized by increased local concentrations of the substrates and improved mass transfer, while the catalyst reduces the activation energy and favors the desired pathway (entry 4). In the next experiment, EtOH was used, as the solvent, for the model reaction in the presence of the catalyst (entry 5), resulting in increased efficiency of the catalyst at room temperature. To evaluate the effect of temperature, the reaction was also conducted at higher temperature. It was observed that increasing the temperature of the model reaction in EtOH to 80 °C improves the reaction progress, and more higher temperatures are not necessary (entry 6). Further optimization experiments were carried out to compare solvent-free conditions with other green solvents, including H2O and EtOH/H2O mixtures. The best yield of the desired product 6a (97%) was obtained in the EtOH/H₂O (1:1 v/v) mixture (entry 8). To optimize the amount of catalyst, various catalyst loadings ranging from 5.0 to 10.0 mg were used in the optimal solvent at different temperatures. It was found that 10.0 mg of CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocatalyst was suitable for the model reaction (entries 9–12). Finally, the individual components of the catalyst, Fe3O4 (inorganic component) and chitosan (organic component), were also investigated at 80 oC (entries 13 and 14). Experimental data demonstrated that the product yield in the presence of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 catalyst was significantly improved compared to using either Fe3O4 or chitosan alone as catalysts, indicating a synergistic effect between the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 components. When the CS-g-PAN catalyst was magnetized with Fe3O4 nanoparticles, there was a substantial increase in its surface area, which contributed to the excellent efficiency observed with the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 catalyst.

Following the optimization process, the overall methodology at its optimized conditions was developed to other aldehydes. Various aldehydes containing different electron-donating groups (–OMe, –OH, –Me) or electron-withdrawing ones (‒NO2, ‒Cl, ‒Br, and ‒CN) were employed, leading to high yields in short reaction times, as presented in Table 2. The observation that electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs) on an aromatic ring generally accelerate reaction rates and enhance yields of the corresponding products compared to benzaldehyde or derivatives bearing electron-donating groups can be explained by considering the rate-determining step in reaction mechanism, which is a well-established principle in organic chemistry.

In the synthesis of 4H-pyran derivatives using the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 catalyst, the condensation of 2-nitrobenzaldehyde (5i), malononitrile (4), and dimedone (7) was selected as the model reaction to determine optimized conditions. Factors such as catalyst loading, solvent, temperature, and reaction time were examined. Initial attempts without a catalyst at 80–100 °C (Table 3, entries 1 and 2) and in MeCN (Table 3, entries 12),afforded minimal desired product 8i. Improved yields were observed in EtOH under reflux conditions, particularly with 10.0 mg of pristine chitosan. To imorove yield further, the reaction was tested with the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 catalyst under various conditions. The best result, 97% isolated yield of 8i, was achieved using 10.0 mg of CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 in EtOH under reflux conditions (Table 3). These conditions were then applied to other aromatic and heterocyclic aldehydes, resulting in high to excellent yields in short reaction times. Aldehydes with electron-donating substituents required longer reaction times compared to those with electron-withdrawing groups, indicating that the rate-determining step is the Knoevenagel condensation (Table 4).

Proposed mechanism for the synthesis of DHPP and 2-amino-3-cyano-4H-pyran derivatives in the presence of CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocatalyst

The multifunctional heterogeneous catalyst, specified as CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite, was employed to facilitate the synthesis of DHPP derivatives. The catalytic efficacy of this nanocomposite stems from the presence of simple or PAN-modified amine functional groups acting as Bronsted basic sites as well as hydroxyl functional groups in conjunction with Fe3+ and Fe2+ centers serving as Lewis acidic sites77. These active sites synergistically promote the activation of reactants.

According to the obtained results and literature data, a plausible mechanism for the formation of DHPPs is proposed as illustrated in Fig. 8. Initially, the carbonyl moieties of ethyl acetoacetate (2) undergo activation facilitated by both the hydroxyl and amine groups, via hydrogen bonding interactions as well as the Lewis acid sites present within the structure of CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 catalyst17, 54, 78, 79. This activation makes the carbonyl group more susceptible to nucleophilic attack by hydrazine hydrate. Subsequent elimination of water and EtOH molecules yields intermediate I, containing the pyrazolone ring system.

Concurrently, intermediate II, –identified as 2-phenylidenemalononitrile– is generated through a Knoevenagel condensation between the catalyst-activated aromatic aldehyde and malononitrile. Subsequently, a Michael addition reaction occurs between the catalyst-activated intermediates I and II to afford intermediate III. This intermediate then undergoes enolization and intramolecular cyclization to produce the intermediate IV.

Finally, tautomerization of the intermediate IV yields the desired DHPP derivatives 6a-p. Following this step, the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 catalyst is then regenerated and available for subsequent catalytic cycles.

A plausible mechanism for the synthesis of 2-amino-3-cyano-4H-pyran derivatives is also illustrated in Fig. 9. According to the obtained results and previous studies77, the aromatic aldehyde is activated by the acidic sites of the catalyst and subsequently reacts with malononitrile, which is activated by the catalyst’s basic sites to form intermediate I (arylidiene malononitrile) via a Knoevenagel condensation. In the second stage, the keto form of dimedone (7) can be in equilibrium with its nucleophilic enol form supported by both hydroxyl and the amine groups as well as Fe cations of the catalyst, allowing it to react with intermediate I through a Michael addition to generate intermediate II. Through a catalyst-assisted intramolecular cyclization process and the tautomerization of intermediate II, the desired products 8a–j are formed80. Finally, the CS-g-PAN/Fe₃O₄ nanocatalyst is returned to the reaction cycle for further use.

Investigating of the recyclability and reusability of CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocatalyst

The principles of green chemistry emphasize the importance of recyclability and reusability of catalysts. While homogeneous catalysts often exhibit higher efficiency, heterogeneous catalysts are favored for their ease of separation and reuse. In this part of our study, the reusability of CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite was evaluated using two model MCRs.

Owing to its magnetic properties, the catalyst 1 was efficiently separated from the reaction mixture using an external magnet after each reaction cycle. Then, the catalyst was thoroughly washed with distilled water and EtOH (96%) to remove any residual impurities, followed by drying. The data presented in Fig. 10 demonstrate that the catalyst retained its catalytic activity over at least five consecutive cycles, with no significant decrease in performance for the synthesis of compounds 8a and 6k derivatives. To further assess the stability and structural integrity of the reused catalyst, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis was conducted. The FT-IR spectrum of the reused nanocatalyst exhibited no detectable changes in its composition, closely matching that of the fresh catalyst. This observation confirms the stability and recoverability of CS-g-PAN/Fe₃O₄ nanocomposite as a robust and reusable catalyst for organic reactions (Fig. S11).

Comparison of CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 catalyst with recently reported protocols for the synthesis of 6a and 8a

Ultimately, the effectiveness of the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocatalyst was assessed in comparison to previously reported protocols. As outlined in Table 5, the CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocatalyst developed in this study exhibits notable efficiency in the rapid synthesis of DHPPs and 4H-pyran derivatives. Additionally, an individual characteristic of this catalyst is its capability to facilitate the formation of these products under environmental friendly conditions and green chemistry principles.

Conclusion

A novel magnetic biopolymer-based nanomaterial was developed through the modification of chitosan (CS) with polyacrylonitrile (PAN) and subsequent magnetization via the in-situ incorporation of Fe3O4 MNPs to afford corresponding CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite. The resulting CS-g-PAN/Fe3O4 nanocomposite was thoroughly characterized using a variety of spectroscopic, microscopic and analytical techniques. The obtained nanocomposite demonstrated exceptional catalytic activity in the efficient synthesis of dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole and 2-amino-3-cyano-4H-pyran derivatives via MCRs strategy. High yields of the desired products were achieved within short reaction times, without the need for laborious work-up procedures. Furthermore, the prepared nanocatalyst exhibited excellent reusability, maintaining its catalytic performance over five consecutive cycles in both MCRs without any substantial loss of its activity.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supporting information of this article.

References

Lambat, T. L. et al. Recent developments in the organic synthesis using nano-NiFe2O4 as reusable catalyst: a comprehensive synthetic & catalytic reusability protocol. Results Chem. 6, 101176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rechem.2023.101176 (2023).

Banifatemi, S. S. et al. Green synthesis of CoFe2O4 nanoparticles using Olive leaf extract and characterization of their magnetic properties. Ceram. Int. 47, 19198–19204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.03.267 (2021).

Baran, T. Pd NPs@Fe3O4/chitosan/pumice hybrid beads: a highly active, magnetically retrievable, and reusable nanocatalyst for cyanation of Aryl halides. Carbohydr. Polym. 237, 116105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116105 (2020).

Gupta, V. & Pal Singh, K. The impact of heterogeneous catalyst on biodiesel production; a review. Mater. Today: Proc. 78, 364–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.10.175 (2023).

Ghosh, N., Patra, M. & Halder, G. Current advances and future outlook of heterogeneous catalytic transesterification towards biodiesel production from waste cooking oil. Sustain. Energy Fuels. 8, 1105–1152. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3SE01564E (2024).

Qu, R., Junge, K. & Beller, M. Hydrogenation of carboxylic acids, esters, and related compounds over heterogeneous catalysts: a step toward sustainable and carbon-neutral processes. Chem. Rev. 123, 1103–1165. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00550 (2023).

Sheldon, R. A. E factors, green chemistry and catalysis: an odyssey. Chem. Commun. 29, 3352–3365 (2008).

Zhu, Y. M. & Shi, X. W. L. Hydrogenation of Ethyl acetate to ethanol over bimetallic Cu-Zn/SiO2 catalysts prepared by means of coprecipitation. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 35, 141 (2014).

Hanifi, S., Dekamin, M. G. & Eslami, M. Magnetic BiFeO3 nanoparticles: a robust and efficient nanocatalyst for the green one-pot three-component synthesis of highly substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidine-2(1H)-one/thione derivatives. Sci. Rep. 14, 22201. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72407-x (2024).

Kamalzare, M., Ahghari, M. R., Bayat, M. & Maleki, A. Fe3O4@chitosan-tannic acid Bionanocomposite as a novel nanocatalyst for the synthesis of Pyranopyrazoles. Sci. Rep. 11, 20021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-99121-2 (2021).

Guo, M., Deng, R., Gao, M., Xu, C. & Zhang, Q. Sustainable recovery of metals from E-Waste using deep eutectic solvents: advances, challenges, and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Green. Sustain. Chem. (2024).

Wu, L. et al. Lithium recovery using electrochemical technologies: advances and challenges. Water Res. 221, 118822 (2022).

Zou, C., Tan, C. & Chen, C. Heterogenization strategies for nickel catalyzed synthesis of polyolefins and composites. Acc. Mater. Res. 4, 496–506. https://doi.org/10.1021/accountsmr.2c00263 (2023).

Ahmad, F. et al. Unique properties of surface-functionalized nanoparticles for bio-application: functionalization mechanisms and importance in application. Nanomaterials 12, 2563 (2022).

Riaz, S. et al. Multifunctional magnetic nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery against cancer: a review of mechanisms, applications, consequences, limitations, and tailoring strategies. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 53, 1291–1327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-025-03712-3 (2025).

Ghobadi, M., Kargar Razi, M., Javahershenas, R. & Kazemi, M. Nanomagnetic reusable catalysts in organic synthesis. Synth. Commun. 51, 647–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/00397911.2020.1819328 (2021).

Fattahi, B. & Dekamin, M. G. Fe3O4/SiO2 decorated Trimesic acid-melamine nanocomposite: a reusable supramolecular organocatalyst for efficient multicomponent synthesis of imidazole derivatives. Sci. Rep. 13, 401. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-27408-7 (2023).

Bushra, R. et al. Recent advances in magnetic nanoparticles: key applications, environmental insights, and future strategies. Sustainable Mater. Technol. 40, e00985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2024.e00985 (2024). https://doi.org/https://doi.

Shakib, P., Dekamin, M. G., Valiey, E., Karami, S. & Dohendou, M. Ultrasound-Promoted Preparation and application of novel bifunctional core/shell Fe3O4@SiO2@PTS-APG as a robust catalyst in the expeditious synthesis of Hantzsch esters. Sci. Rep. 13, 8016. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33990-7 (2023).

FaniMoghadam, H., Dekamin, M. G. & Rostami, N. Para-Aminobenzoic acid grafted on silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles: a highly efficient and synergistic organocatalyst for on-water synthesis of 2,3-dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-ones. Res. Chem. Intermed. 48, 3061–3089. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11164-022-04736-3 (2022).

Falciglia, P. P. et al. Physico-magnetic properties and dynamics of magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles (MNPs) under the effect of permanent magnetic fields in contaminated water treatment applications. Sep. Purif. Technol. 296, 121342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2022.121342 (2022).

Nourmohammadi, M. et al. Magnetic nanocomposite of crosslinked Chitosan with 4,6-diacetylresorcinol for gold immobilization (Fe3O4@CS/DAR-Au) as a catalyst for an efficient one-pot synthesis of Propargylamine. Mater. Today Commun. 29, 102798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2021.102798 (2021).

Manohar, A., Geleta, D. D., Krishnamoorthi, C. & Lee, J. Synthesis, characterization and magnetic hyperthermia properties of nearly monodisperse CoFe2O4 nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 46, 28035–28041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.07.298 (2020).

Ansari, S. M. et al. Eco-friendly synthesis, crystal chemistry, and magnetic properties of manganese-substituted CoFe2O4 nanoparticles. ACS Omega. 5, 19315–19330. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b02492 (2020).

Lau, E. C. H. T. et al. Direct purification and immobilization of his-tagged enzymes using unmodified nickel ferrite NiFe2O4 magnetic nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 13, 21549. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48795-x (2023).

Ishani, M., Dekamin, M. G. & Alirezvani, Z. Superparamagnetic silica core-shell hybrid attached to graphene oxide as a promising recoverable catalyst for expeditious synthesis of TMS-protected cyanohydrins. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 521, 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2018.02.060 (2018).

Taheri-Torbati, M. & Eshghi, H. Fe3O4@CS-Ni: an efficient and recyclable magnetic nanocatalyst for α-alkylation of ketones with benzyl alcohols by borrowing hydrogen methodology. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 36, e6838. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.6838 (2022).

Eivazzadeh-Keihan, R. et al. Fe3O4/GO@melamine-ZnO nanocomposite: a promising versatile tool for organic catalysis and electrical capacitance. Colloids Surf., A. 587, 124335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.124335 (2020).

Jassim, G. S. et al. An Fe 3 O 4 supported O-phenylenediamine based Tetraaza schiff base-Cu (ii) complex as a novel nanomagnetic catalytic system for synthesis of Pyrano [2, 3-c] pyrazoles. Nanoscale Adv. 5, 7018–7030 (2023).

Sharma, M., Sharma, P., Janu, V. C. & Gupta, R. Evaluation of adsorptive capture and release efficiency of MNPs-SA@Cu MOF composite beads toward U(VI) and Th(IV) ions from an aqueous media. Langmuir 40, 541–553. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.3c02767 (2024).

Aghashiri, Z., Ghassamipour, S., Jamalian, A. & Emadi, M. Synthesis and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2@APIDSO3H as a novel and efficient magnetic nanocatalyst in Pechmann condensation. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 38, e7716. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.7716 (2024).

Aberdeen, S., An Hur, C., Calì, E., Vandeperre, L. J. & Ryan, M. P. Acid resistant functionalised magnetic nanoparticles for radionuclide and heavy metal adsorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 608, 1728–1738 (2021).

Goetjen, T. A. et al. Metal-organic framework (MOF) materials as polymerization catalysts: a review and recent advances. Chem. commun. (2020).

Baran, T., Sargin, I., Kaya, M. & Menteş, A. Green heterogeneous Pd(II) catalyst produced from chitosan-cellulose micro beads for green synthesis of biaryls. Carbohydr. Polym. 152, 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.06.103 (2016).

Faísca Phillips, A. M. Applications of carbohydrate-based organocatalysts in enantioselective synthesis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 7291–7303. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.201402689 (2014).

Warkar, S. G. Synthesis and applications of biopolymer /FeO nanocomposites: a review. J. New. Mater. Electrochem. Syst. (2022).

Abou-Okeil, A., Refaei, R., Moustafa, S. E. & Ibrahim, H. M. Magnetic hydrogel scaffold based on hyaluronic acid/chitosan and gelatin natural polymers. Sci. Rep. 14, 28206. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78696-6 (2024).

Mittal, N., Kundu, A. & Pathania, A. A review of the chemical synthesis of magnetic nano-particles and biomedical applications. Mater. Today: Proc. (2023).

Wiranowska, M. Advances in the use of Chitosan and chlorotoxin- functionalized Chitosan polymers in drug delivery and detection of glioma – a review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 7, 100427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carpta.2024.100427 (2024).

Sruthi, P. R. & Anas, S. An overview of synthetic modification of nitrile group in polymers and applications. J. Polym. Sci. 58, 1039–1061 (2020).

Hingrajiya, R. D. & Patel, M. P. Fe3O4 modified Chitosan based co-polymeric magnetic composite hydrogel: Synthesis, characterization and evaluation for the removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 244, 125251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125251 (2023).

Younus, H. A. et al. Multicomponent reactions (MCR) in medicinal chemistry: a patent review (2010–2020). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 31, 267–289 (2020).

Shen, X., Hong, G. & Wang, L. Recent advances in green multi-component reactions for heterocyclic compound construction. Org. Biomol. Chem. 23, 2059–2078. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4OB01822B (2025).

Gensch, T., Hopkinson, M. N., Glorius, F. & Wencel-Delord, J. Mild metal-catalyzed C-H activation: examples and concepts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45 (10), 2900–2936 (2016).

Ahmad, A., Rao, S. & Shetty, N. S. Green multicomponent synthesis of pyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives: current insights and future directions. RSC Adv. 13, 28798–28833 (2023).

Biswas, S. K. & Das, D. One-pot synthesis of Pyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives via multicomponent reactions (MCRs) and their applications in medicinal chemistry. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. (2021).

Hemmerling, F. & Hahn, F. Biosynthesis of oxygen and nitrogen-containing heterocycles in polyketides. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 12, 1512–1550 (2016).

Hajihasani Bafghi, M., Bamoniri, A. & Mirjalili, B. B. F. Talc as a natural mineral catalyst for the one pot-three component synthesis of benzo[f]chromene, dihydropyrano[3,2-c]chromene, and tetrahydrobenzo[b]pyran derivatives under different conditions. Sci. Rep. 15, 14167. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95727-y (2025).

Mali, G. et al. Design, Synthesis, and biological evaluation of densely substituted dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazoles via a taurine-catalyzed green multicomponent approach. ACS Omega. 6, 30734–30742 (2021).

Nguyen, H. T. et al. A new pathway for the Preparation of pyrano[2,3-c]pyrazoles and molecular Docking as inhibitors of p38 MAP kinase. ACS Omega. 7, 17432–17443. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c01814 (2022).

Guan, Z. et al. Green synthesis of nanoparticles: current developments and limitations. Environ. Technol. Innov. (2022).

Nagasundaram, N., Kokila, M., Sivaguru, P., Santhosh, R. & Lalitha, A. SO3H@carbon powder derived from waste orange peel: an efficient, nano-sized greener catalyst for the synthesis of dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives. Adv. Powder Technol. 31, 1516–1528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2020.01.012 (2020).

Valiey, E., Dekamin, M. G. & Alirezvani, Z. Melamine-modified Chitosan materials: an efficient and recyclable bifunctional organocatalyst for green synthesis of densely functionalized bioactive dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole and benzylpyrazolyl coumarin derivatives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 129, 407–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.01.027 (2019).

Karami, S., Dekamin, M. G., Valiey, E. & Shakib, P. DABA mnps: a new and efficient magnetic bifunctional nanocatalyst for the green synthesis of biologically active pyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole and benzylpyrazolyl coumarin derivatives. New J. Chem. 44, 13952–13961. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0NJ02666B (2020).

Angela, S. et al. Aminoacid functionalised magnetite nanoparticles Fe3O4@AA (AA = Ser, Cys, Pro, Trp) as biocompatible magnetite nanoparticles with potential therapeutic applications. Sci. Rep. 14, 26228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76552-1 (2024).

Krzeszewski, M. et al. Computer-generated, mechanistic networks assist in assigning the outcomes of complex multicomponent reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 15636–15644. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5c02846 (2025).

Ilkhanizadeh, S., Khalafy, J. & Dekamin, M. G. Sodium alginate: A biopolymeric catalyst for the synthesis of novel and known polysubstituted pyrano[3,2-c]chromenes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 140, 605–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.08.154 (2019).

Kumar, D. et al. The value of Pyrans as anticancer scaffolds in medicinal chemistry. RSC Adv. 7, 36977–36999 (2017).

Srikrishna, D., Godugu, C. & Dubey, P. K. A review on Pharmacological properties of coumarins. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 18, 113–141 (2018).

El-Bana, G. G., Salem, M. A., Helal, M. H., Alharbi, O. & Gouda, M. A. A review on the recent multicomponent synthesis of 4 h-pyran derivatives. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 21, 73–91. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570193X19666220527163846 (2024).

Gangu, K. K., Maddila, S., Mukkamala, S. B. & Jonnalagadda, S. B. Synthesis, structure, and properties of new Mg (II)-metal–organic framework and its prowess as catalyst in the production of 4 H-Pyrans. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 56, 2917–2924 (2017).

Javed, M. N. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and application of natural occurring hydroxy functionalized benzoate based ionic liquids as catalyst for 2-amino-7-hydroxy-4 h-chromene derivatives under ultrasound irradiation. J. Mol. Struct. 1336, 142100 (2025).

Rostami, N., Dekamin, M. G., Valiey, E. & Fanimoghadam, H. Chitosan-EDTA-Cellulose network as a green, recyclable and multifunctional biopolymeric organocatalyst for the one-pot synthesis of 2-amino-4 H-pyran derivatives. Sci. Rep. 12, 8642 (2022).

Zamanfar, S., Daraie, M., Azizi, N., Ghafuri, H. & Mirjafary, Z. Facile synthesis of sulfonic acid-based ionic liquid-decorated magnetic Halloysite as an efficient catalyst for the multicomponent synthesis of 2-amino 4 H Pyran derivatives. J. Alloys Compd. 976, 173358 (2024).

Achagar, R. et al. Exploration of Na2CaP2O7 as a nanocatalyst for eco-conscious synthesis of 4 H-Pyran derivatives: computational examination utilizing DFT and Docking techniques. Chem. Afr. 7, 1829–1848 (2024).

Dekamin, M. G., Eslami, M. & Maleki, A. Potassium phthalimide-N-oxyl: a novel, efficient, and simple organocatalyst for the one-pot three-component synthesis of various 2-amino-4H-chromene derivatives in water. Tetrahedron 69, 1074–1085 (2013).

Dekamin, M. G. & Eslami, M. Highly efficient organocatalytic synthesis of diverse and densely functionalized 2-amino-3-cyano-4 H-pyrans under mechanochemical ball milling. Green Chem. 16, 4914–4921. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4GC00411F (2014).

Sun, Q., Aguila, B., Perman, J. A., Nguyen, N. & Ma, S. Flexibility matters: cooperative active sites in covalent organic framework and threaded ionic polymer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138 48, 15790–15796 (2016).

Dekamin, M. G., Azimoshan, M. & Ramezani, L. Chitosan: a highly efficient renewable and recoverable bio-polymer catalyst for the expeditious synthesis of α-amino nitriles and Imines under mild conditions. Green Chem. 15, 811–820. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3GC36901C (2013).

Domszy, J. G. & Roberts, G. A. F. Evaluation of infrared spectroscopic techniques for analysing Chitosan. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 186, 1671–1677 (1985).

Zohrevand, M., Nashibi, N., Dekamin, M. G. & Sarvary, A. Nano ordered polyacrylonitrile-grafted Chitosan as a robust biopolymeric catalyst for efficient synthesis of highly substituted pyrrole derivatives. Sci. Rep. 15, 2563. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05504-0 (2025).

Nashibi, N., Dekamin, M.G. & Maleki, A. Nano‑ordered polyacrylonitrile grafted to chitosan as a bio‑based and eco‑friendly organocatalyst for the one‑pot synthesis of 2‑amino‑3‑cyano‑4H‑pyran derivatives. Res. Chem. Intermed. 51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11164-025-05782-3 (2025).

Raja, P. B., Munusamy, K. R., Perumal, V. & Ibrahim, M. N. M. In Nano-Bioremediation: Fundamentals and Applications (eds. Hafiz M. N. I. et al.) 57–83 (Elsevier, 2022).

Julkapli, N. M., Ahmad, Z. & Akil, H. M. X-ray diffraction studies of cross linked chitosan with different cross linking agents for waste water treatment application. AIP Conf. Proc. 1202, 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3295578 (2010).

Chernova, E. et al. A comprehensive study of synthesis and analysis of anisotropic iron oxide and oxyhydroxide nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 12, 4321 (2022).

Pivarčiová, L., Rosskopfová, O., Galamboš, M., Rajec, P. & Hudec, P. Sorption of pertechnetate anions on Chitosan. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 308, 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-015-4351-7 (2016).

Rubio-Gaspar, A. et al. Metal node control of brønsted acidity in heterobimetallic titanium–organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 3855–3860 (2023).

Dekamin, M.G., Karimi, Z. & Farahmand, M. Tetraethylammonium 2-(N-hydroxycarbamoyl)benzoate: a powerful bifunctional metal-free catalyst for efficient and rapid cyanosilylation of carbonyl compounds under mild conditions. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2, 1375–1381. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2CY20037F (2012).

Dekamin, M.G., Varmira, K., Farahmand, M., Sagheb-Asl, S. & Karimi, Z. Organocatalytic, rapid and facile cyclotrimerization of isocyanates using tetrabutylammonium phthalimide-N-oxyl and tetraethylammonium 2-(carbamoyl)benzoate under solvent-free conditions. Catal. Commun. 12, 226–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catcom.2010.08.018 (2010).

Hassanzadeh, N., Dekamin, M. G. & Valiey, E. A supramolecular magnetic and multifunctional Titriplex V-grafted Chitosan organocatalyst for the synthesis of acridine-1,8-diones and 2-amino-3-cyano-4H-pyran derivatives. Nanoscale Adv. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4NA00264D (2025).

Tamoradi, T. et al. Synthesis of Eu(III) fabricated spinel ferrite based surface modified hybrid nanocomposite: study of catalytic activity towards the facile synthesis of tetrahydrobenzo[b]pyrans. J. Mol. Struct. 1219, 128598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128598 (2020).

Saffar, A. Tetrahydrodipyrazolopyridine covalently immobilized on silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles as a basic heterogeneous catalyst for multicomponent synthesis of dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives and Knoevenagel condensation. Sci. Rep. 15, 23698. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07368-w (2025).

Beiranvand, M. & Habibi, D. Design, Preparation and application of the semicarbazide-pyridoyl-sulfonic acid-based nanocatalyst for the synthesis of Pyranopyrazoles. Sci. Rep. 12, 14347. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18651-5 (2022).

Maleki, B. et al. Silica-coated magnetic NiFe2O4 nanoparticles-supported H3PW12O40; synthesis, preparation, and application as an efficient, magnetic, green catalyst for one-pot synthesis of tetrahydrobenzo[b]pyran and pyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives. Res. Chem. Intermed. 42, 3071–3093. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11164-015-2198-8 (2016).

Moosavi-Zare, A. R. Goudarziafshar, H. & Saki, K. Synthesis of Pyranopyrazoles using nano‐Fe‐ [phenylsalicylaldiminemethylpyranopyrazole] Cl2 as a new schiff base complex and catalyst. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 32, e3968 (2018).

Upadhyay, A. et al. Electrochemically induced one pot synthesis of 1,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]-pyrazole-5-carbonitrile derivatives via a four component-tandem strategy. Tetrahedron Lett. 58, 1245–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.01.049 (2017).

Moosavi-Zare, A. R., Goudarziafshar, H. & Saki, K. Synthesis of Pyranopyrazoles using nano-Fe-[phenylsalicylaldiminemethylpyranopyrazole]Cl2 as a new schiff base complex and catalyst. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 32, e3968. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.3968 (2018).

Nazari, S., Keshavarz, M. & Amberlite-supported L-prolinate: a novel heterogeneous organocatalyst for the three-component synthesis of 4H-pyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 87, 539–545. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1070363217030252 (2017).

Babaee, S., Zarei, M., Sepehrmansourie, H., Zolfigol, M. A. & Rostamnia, S. Synthesis of metal–organic frameworks MIL-101(Cr)-NH2 containing phosphorous acid functional groups: application for the synthesis of N-Amino-2-pyridone and Pyrano [2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives via a cooperative vinylogous anomeric-based oxidation. ACS Omega. 5, 6240–6249. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b02133 (2020).

Safaei-Ghomi, J., Shahbazi-Alavi, H. & Heidari-Baghbahadorani, E. ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles as a robust and reusable magnetically catalyst in the four component synthesis of [(5-hydroxy-3-methyl-1H-pyrazol-4yl) (phenyl) Methyl]propAnedinitriles and substituted 6-Amino-Pyrano[2,3-c]Pyrazoles. J. Chem. Res. 39, 410–413. https://doi.org/10.3184/174751915X14358475706316 (2015).

Nguyen, H. T. et al. A new pathway for the Preparation of Pyrano [2, 3-c] pyrazoles and molecular Docking as inhibitors of p38 MAP kinase. ACS Omega. 7, 17432–17443 (2022).

Kamel, M. Convenient Synthesis, characterization, cytotoxicity and toxicity of pyrazole derivatives. Acta Chim. Slov. 62, 136–151. https://doi.org/10.17344/acsi.2014.828 (2015).

Yousefi, M. R., Goli-Jolodar, O., Shirini, F. & Piperazine An excellent catalyst for the synthesis of 2-amino-3-cyano-4H-pyrans derivatives in aqueous medium. Bioorg. Chem. 81, 326–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.08.026 (2018).

Jin, T. S. et al. Hexadecyldimethyl benzyl ammonium bromide: an efficient catalystfor a clean one-pot synthesis of tetrahydrobenzopyran derivatives in water. Arkivoc 14, 78–86 (2006).

Mirza-Aghayan, M., Mohammadi, M., Boukherroub, R. & Ravanavard, K. Functionalized reduced graphene oxide as a useful and efficient base catalyst for the Preparation of 4 H‐pyran and pyran‐like Tacrine compounds and their antibacterial activity. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 60, 252–263 (2023).

Mashhadinezhad, M., Mamaghani, M., Rassa, M. & Shirini, F. A facile green synthesis of Chromene derivatives as antioxidant and antibacterial agents through a modified natural soil. ChemistrySelect 4, 4920–4932. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.201900405 (2019).

Hiremath, P. B. & Kantharaju, K. An efficient and facile synthesis of 2-amino‐4H‐pyrans &tetrahydrobenzo [b] Pyrans catalysed by WEMFSA at room temperature. ChemistrySelect 5, 1896–1906 (2020).

Zonouz, A., Moghani, D. & Okhravi, S. A facile and efficient protocol for the synthesis of 2-amino-3-cyano-4H-pyran derivatives at ambient temperature. Curr. Chem. Lett. 3, 71–74 (2014).

Ramesh, R., Jayamathi, J., Karthika, C., Małecki, J. G. & Lalitha, A. An organocatalytic newer synthetic strategy toward the access of polyfunctionalized 4H-pyrans via multicomponent reactions. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 40, 502–515 (2020).

Hu, H., Qiu, F., Ying, A., Yang, J. & Meng, H. An environmentally benign protocol for aqueous synthesis of Tetrahydrobenzo[b]pyrans catalyzed by cost-effective ionic liquid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 6897–6909 (2014).

Magar, R. R., Pawar, G. T., Gadekar, S. P. & Lande, M. K. Fe-MCM-22 catalyzed multicomponent synthesis of dihydropyrano [2, 3-c] pyrazole derivatives (2017).

El-Assaly, S., Ismail, A., Bary, H. & Abouelenein, M. Synthesis, molecular Docking studies, and antimicrobial evaluation of Pyrano [2, 3-c] pyrazole derivatives. Curr. Chem. Lett. 10, 309–328 (2021).

Badbedast, M., Abdolmaleki, A. & Khalili, D. Copper-decorated magnetite polydopamine composite (Fe3O4@ PDA): an effective and durable heterogeneous catalyst for Pyranopyrazole synthesis. ChemistrySelect 7, e202203199 (2022).

Kamalzare, M., Bayat, M. & Maleki, A. Green and efficient three-component synthesis of 4H-pyran catalysed by CuFe2O4@ starch as a magnetically recyclable Bionanocatalyst. R. Soc. Open. Sci. 7, 200385. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.200385 (2020).

Ahankar, H., Ramazani, A., Slepokura, K., Lis, T. & Joo, S. W. One-pot synthesis of substituted 4$ H $-chromenes by nickel ferrite nanoparticles as an efficient and magnetically reusable catalyst. Turk. J. Chem. 42, 719–734 (2018).

Kalantari, F. et al. SO3H-Functionalized epoxy-immobilized Fe3O4 core–shell magnetic nanoparticles as an efficient, reusable, and eco-friendly catalyst for the sustainable and green synthesis of Pyran and pyrrolidinone derivatives. ACS Omega. 8, 25780–25798. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c01068 (2023).

Sabitha, G., Arundhathi, K., Sudhakar, K., Sastry, B. & Yadav, J. Cerium (III) chloride–catalyzed one-pot synthesis of tetrahydrobenzo [b] Pyrans. Synth. Commun. 39, 433–442 (2009).

Funding

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Research Council of Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran (IUST) for their financial support (grant no 160/25285). We would also like to acknowledge the support of the Iran Nanotechnology Initiative Council (INIC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Niloufar Nashibi: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; validation; writing of initial draft. Mohammad G. Dekamin: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; project administration; supervision; editing of the initial draft. Ali Maleki: Funding acquisition; project administration; supervision; writing of the initial draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nashibi, N., Dekamin, M.G. & Maleki, A. Preparation of magnetic decorated polyacrylonitrile-grafted chitosan as a new bio-inspired nanocatalyst for the synthesis of dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole and 2-amino-3-cyano-4H-pyran derivatives. Sci Rep 15, 44789 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24359-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24359-z