Abstract

Recent advances in deep learning have led to the widespread use of pre-trained large-scale speech models, such as wav2vec 2.0 (w2v2), in voice spoofing detection. However, the interpretability of such models remains a critical challenge due to their complex internal representations. In this paper, we propose iWAX, an interpretable voice spoofing countermeasure that combines a fine-tuned w2v2 front-end with the AASIST back-end, and an XGBoost classifier. iWAX leverages the feature importance mechanism of XGBoost to identify which temporal segments and frequency bands of the audio w2v2 prioritizes during spoofing detection. To enable frequency-based interpretability, we apply sinc filters to isolate specific spectral regions of input raw waveforms. Temporal analysis is conducted by selecting key features extracted from w2v2 and analyzing their contribution across time. Experimental results on the ASVspoof 2019 LA dataset demonstrate that iWAX not only outperforms baseline models such as AASIST and w2v2-AASIST but also provides human-understandable explanations of its predictions. Further analysis with LightGBM validates the robustness of our approach across different boosting models. Overall, iWAX offers a compelling balance between interpretability and performance, addressing the limitations of both traditional machine learning and modern deep learning-based countermeasures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Voice spoofing countermeasures based on classical machine learning models, such as Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) and Support Vector Machines (SVM), typically rely on handcrafted acoustic features1,2,3. Especially, Rahmeni et al.4,5 proposed interpretable and lightweight countermeasures by integrating handcrafted features like Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC) and Linear Prediction Coefficients (LPC) with XGBoost. With the advancement of deep learning, mel-spectrogram and Constant-Q Transforms (CQT), which lie closer to raw audio than MFCC or LPC, are merged with deep learning-based countermeasures for voice spoofing detection6,7. While handcrafted features offer the advantage of computational simplicity, they typically require extensive hyperparameter tuning and are limited in their ability to capture diverse acoustic patterns. To address these limitations, models such as SincNet8, RawNet9, RawNet210, and AASIST11 adopt end-to-end deep learning architectures that operate directly on raw waveforms as input, shifting away from handcrafted features and laying the groundwork for more data-driven approaches to spoofing detection.

More recently, the field has seen significant progress through the development of pre-trained large-scale speech models such as wav2vec 2.012,13, Whisper14, and WavLM15. Among these, wav2vec 2.0 (briefly, w2v2), originally designed for speech recognition, has demonstrated strong transferability across various speech-related tasks. Lee et al.16 employed w2v2 for feature extraction in spoofing-aware speaker verification, while Tak et al. utilized w2v2 front-end with fine-tuning to enhance voice spoofing detection performance17. Additionally, Tak et al.18 combined a w2v2 front-end with the AASIST countermeasure to detect spoofed speech, and Kang et al.19 conducted an empirical study on optimizing the w2v2-AASIST framework by adjusting the total and frozen layers within the pre-trained w2v2 model. They found that a variant of w2v2, XLS-R(1B), when paired with AASIST, significantly improved the equal error rate (EER) performance compared to conventional AASIST models. These recent studies illustrate the effectiveness of using pre-trained large-scale speech models as front-end feature extractors, which can be integrated with existing deep learning models to enhance downstream task performance.

However, large-scale deep learning models often suffer from limited interpretability due to their large number of parameters. Recent efforts have aimed to interpret the internal representations of w2v2. Singla et al.20 analyzed high-dimensional embeddings extracted from audio transformer models, demonstrating that such models can capture high-level linguistic features, including fluency and pronunciation. Grosz et al.21 explored the impact of fine-tuning w2v2 on Finnish speech data, employing visualization and latent embedding clustering techniques to better understand the model’s behavior. Dieck et al.22 investigated w2v2 from the perspectives of frequency and phonetic information. However, these studies have primarily focused on speech recognition and phonetic analysis, and lack interpretability analysis in the context of voice spoofing detection.

In a separate line of research, Li et al.23 incorporated interpretability into the model architecture by combining w2v2 with utterance-level attentive features, thereby enhancing transparency in the decision-making process. They introduced a class activation-based representation that highlights the key audio frames most relevant to spoofing detection. However, in the audio domain, frame-level attention may not be sufficient for meaningful interpretation. In computer vision, techniques such as Grad-CAM24 and attention map25 are widely used to identify salient regions that influence model predictions, often aligning with human intuition, for instance, distinguishing a dog from a cat based on visible characteristics. In contrast, for raw audio waveforms, even when a model highlights a particular segment as important for spoofing detection, it is often unclear to human listeners what makes that segment suspicious. In other words, the connection between model attention and interpretable acoustic cues is not always apparent. This highlights the need for modality-aware interpretability techniques that account for the unique challenges of the audio domain, particularly in voice spoofing detection.

The next key question is determining which features of the audio should be prioritized when developing an interpretability framework. Recently, Grinberg et al.26 proposed an explainable AI method to reveal which temporal regions that transformer-based audio deepfake detection models rely on. Chhibber et al.27 developed a probabilistic attribute embedding approach based on interpretability AI for spoofed speech characterization. In the context of voice spoofing detection, Choi et al.6 split audio spectrograms along the frequency axis to extract frequency features from distinct spectral regions. Similarly, Kwak et al.28 employed a data augmentation technique known as Frequency Feature Masking (FFM), which randomly masks frequency bands to enhance model robustness against noise in specific frequency ranges. In addition, Salvi et al.29 highlights the importance of frequency subband-based analysis for voice spoofing detection. These studies demonstrated the effectiveness of frequency-based analysis in improving spoofing detection performance, underscoring the importance of considering spectral characteristics in model design. Building on these insights, we propose the incorporation of frequency-resolved features into our interpretability framework. By identifying discriminative frequency bands, our approach enables more meaningful and human-understandable explanations of why specific audio segments are classified as spoofed, thereby improving both interpretability and detection performance.

In the context of the preceding research, this study seeks to address the following three key questions:

-

How can we build an interpretable model that leverages the representational power of a pre-trained large-scale speech model as a feature extractor while also improving performance?

-

How can we identify the specific regions within an audio sample that the model attends to during spoofing detection?

-

How can we interpret the internal representations of large-scale deep learning-based countermeasures, particularly in the frequency domain, using feature importance mechanisms from traditional machine learning models?

To address these questions, we propose a novel framework iWAX—an interpretable voice spoofing countermeasure that combines wav2vec 2.0 fine-tuned with AASIST, and XGBoost classifier–that:

-

integrates a pre-trained speech model (wav2vec 2.0) with temporally and spectrally resolved interpretability, enhancing transparency;

-

and simultaneously achieves improved performance and interpretability compared to baseline models.

The code of our proposed method is publicly available ( https://github.com/duneag2/iwax).

Backgrounds

XGBoost

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) is a gradient boosting framework that augments conventional Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) by incorporating both L1 and L2 regularization terms, thereby effectively controlling model complexity and mitigate overfitting30. In each boosting iteration, XGBoost constructs a new decision tree aimed at minimizing the residual error, while applying a shrinkage factor to modulate the contribution of each tree. This process of iterative refinement, combined with column subsampling where a random subset of features is selected at each split, enhances the model’s generalization ability and computational efficiency.

Within the iWAX framework, XGBoost plays a critical role in ensuring both model interpretability and computational efficiency. Its intrinsic feature importance mechanism enables a systematic analysis of key features, such as specific frequency bands and temporal intervals, that most significantly influence the model’s decision-making process.

Wav2vec 2.0

Wav2vec 2.0 is a self-supervised learning framework for speech representation, initially developed for automatic speech recognition (ASR) tasks12,13. It processes raw audio waveforms through a series of Transformer layers to extract high-dimensional feature representations that capture salient characteristics of speech signals. Although originally designed for ASR, the model’s strong transfer learning capabilities have enabled its successful adaptation to a variety of downstream tasks, including voice spoofing detection16,18,19. By fine-tuning wav2vec 2.0 on task-specific datasets, the model can effectively capture complex acoustic patterns that are often imperceptible through traditional handcrafted features19, thereby improving performance in scenarios requiring robust and discriminative speech feature extraction.

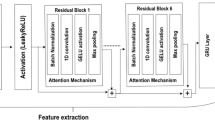

AASIST

Audio Anti-Spoofing using Integrated Spectro-Temporal Graph Attention Networks (AASIST) is an end-to-end deep learning framework specifically designed for voice spoofing detection proposed by Jung et al.11. This architecture directly accepts raw waveforms as input and employs integrated spectro-temporal graph attention mechanisms to learn discriminative features across both time and frequency domains. The AASIST backend is initially randomly initialized and subsequently fine-tuned on spoofing detection tasks, thereby optimizing its capacity to distinguish between genuine and spoofed audio signals. When integrated with the robust feature extraction capabilities of wav2vec 2.0, AASIST significantly improves the overall detection performance19. Moreover, it facilitates interpretability by enabling analysis of the specific temporal and spectral attributes that influence the classification outcomes.

Methods

This section presents iWAX, an interpretable framework that integrates wav2vec 2.0 (w2v2), AASIST, and XGBoost for voice spoofing detection. Overall, the framework fine-tunes w2v2 for voice spoofing detection through integration with AASIST, and then connects the tuned w2v2 to XGBoost to perform the final classification task. We describe the overall iWAX framework, as illustrated in Fig. 1, and detail its analytical methodology.

Fine-tuning wav2vec 2.0 within the w2v2-AASIST framework

The iWAX architecture begins with joint fine-tuning the w2v2 front-end and the AASIST back-end for voice spoofing detection. We initialize both components using publicly available pre-trained weights: w2v2 from Hugging Face (https://huggingface.co/facebook/wav2vec2-xls-r-1b) and AASIST from its official GitHub repository (https://github.com/clovaai/aasist). These modules are integrated and trained end-to-end to optimize performance on our target task.

We employ XLS-R(1B), a large-scale pre-trained variant of w2v2 consisting of 48 Transformer layers and approximately 965 million parameters. Following the strategy proposed by Kang et al.19, we reconfigure the model by selecting the first (leftmost) 12 Transformer layers. Among these, the first 9 layers are frozen to retain general speech representations, while the remaining 3 layers are fine-tuned together with the AASIST back-end. This partial fine-tuning strategy enables the model to preserve foundational acoustic features from pre-training while adapting effectively to spoofing-specific patterns.

Importance of fine-tuning wav2vec 2.0

We observed that directly employing the original pre-trained w2v2 model in conjunction with the XGBoost-based countermeasure, without task-specific fine-tuning, resulted in suboptimal performance. This observation underscores the domain gap between the general-purpose speech representations learned during pre-training and the specific requirements for spoofing detection. Based on these findings, we conclude that fine-tuning w2v2, particularly in conjunction with the AASIST back-end, is essential for bridging this gap. This process effectively aligns the model’s learned features with the specific characteristics of spoofed speech, resulting in a substantial performance improvement.

Interpreting wav2vec 2.0 via the feature importance mechanism of XGBoost

XGBoost is a scalable and efficient gradient tree boosting framework that incorporates regularization techniques. One of its key strengths is the built-in feature importance mechanism, which provides insight into the relative contribution of each input variable. In particular, feature importance is quantified using the F-score, which reflects the frequency with which a feature is used to split data across all boosting rounds. This metric enables us to interpret how different features, extracted from the w2v2 front-end, affect the model’s predictions, thereby enhancing the explainability of the overall iWAX framework.

Temporal analysis

Utilizing XGBoost’s feature importance mechanism, we analyze which temporal segments of the input most influence the model’s predictions. This analysis involves two main steps: feature selection and temporal importance extraction, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. The output of the final Transformer layer in w2v2 is an extracted audio feature matrix of shape \(\mathbb {R}^{T \times F}\), where T denotes the time dimensions and F the feature dimensions.

In the feature selection step, we first select three intermediate row vectors of shape \(\mathbb {R}^{1 \times F}\) from the output of the fine-tuned w2v2 model. These vectors are chosen at fixed relative positions corresponding to time points \(T = \frac{1}{4}, \frac{2}{4}, \frac{3}{4}\), avoiding the very beginning and end of the utterance, where silence is often observed in the ASVspoof 2019 dataset. This choice is also supported by prior work suggesting that silence may affect spoofing detection performance31. Importantly, these vectors are not sampled from the raw waveform but from high-level representations produced by the w2v2. This captures global audio context through receptive fields and self-attention mechanisms within w2v2 architecture. Consequently, we assume that our analysis is less sensitive to the exact sampling positions.

These vectors are then used to train an XGBoost classifier. From this model, we identify the top three features that are most frequently selected across these time points, indicating consistent importance. Next, in the temporal importance extraction step, we select three column vectors of shape \(\mathbb {R}^{T \times 1}\) corresponding to the identified top three features. A second XGBoost model is trained using these three temporal trajectories as input. By examining the resulting feature importances, we infer which specific time intervals are most critical for the classification decision.

Frequency band-based analysis

Our hypothesis is inspired by the work of Choi et al.6 and Kwak et al.28, who highlight the significance of analyzing audio signals in terms of frequency bands. We expect that the model attends to specific frequency bands and aim to investigate how manipulating these frequency bands influences detection outcomes. Since w2v2 operates on raw waveform inputs, we utilize sinc filters8 to filter out particular frequency ranges of the audio samples. SincNet, a CNN architecture, uses band-pass filters, called sinc filters, based on the sinc function, defined as \(sinc(x) = sin(x)/x\). The filtering operation is expressed as:

where \(f_1\) and \(f_2\) represent the low and high cutoff frequencies, respectively. Here, n denotes the discrete time index of the filter kernel, which is symmetric around zero. We set the kernel size to 513, resulting in \(n \in [-256, 256]\) where \(n \in \mathbb {Z}\).

Unlike the original SincNet implementation where cutoff frequencies are learned during training, we fix the filter parameters manually to target specific frequency ranges of interest. In accordance with the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem, for accurate signal representation, the sampling rate must be at least twice the highest frequency contained in the signal. Consequently, the cutoff frequencies of sinc filters are constrained to not exceed half the audio sampling rate, i.e., 8,000 Hz for a 16,000 Hz sample rate. Frequency bands are selected on a logarithmic scale to align with the perceptual scale of pitch. We would like to note that we used manually defined ranges to avoid the computational overhead of optimizing frequency bands.

We compare model performance using sinc-filtered inputs against the baseline model that operates on the full frequency spectrum, as illustrated in Fig. 2b. If the equal error rate (EER) and feature importance scores obtained from the frequency-limited inputs are comparable to those derived from the full-spectrum baseline, this strongly indicates that the model does not rely uniformly on the entire frequency range. Instead, it inherently focuses on the specific frequency band under analysis. Such a result not only validates the effectiveness of the selected spectral region but also provides empirical evidence that the model’s decision-making process is predominantly influenced by acoustic cues within that band.

Experiments

Experimental setup

We conducted experiments using ASVspoof 2019 Logical Access (LA) dataset32. The dataset is divided into training, development, and evaluation sets. Specifically, the training set consists of 22,800 spoof and 2580 bonafide samples, while the development set includes 22,296 spoof and 2548 bonafide samples. The evaluation set comprises 63,882 spoof and 7355 bonafide samples. Our model is trained using the training set and assessed with the development and evaluation sets. Following the ASVspoof 2019 competition criterion, we use EER to evaluate model performance. Each audio sample is approximately 4 s long and consists of 64,600 data points recorded at a sampling rate of 16,000 Hz.

It is noteworthy that during the fine-tuning of w2v2 within the w2v2-AASIST framework, only the training set was utilized to avoid any data leakage. The XLS-R(1B) model contains approximately 965 million parameters, while AASIST has 297 thousand. In contrast, XGBoost is remarkably lightweight, with the entire model size measured in kilobytes. Using a GPU server equipped with two TESLA V100 graphics cards, training and evaluating the w2v2-AASIST model takes approximately 6 hours. After fine-tuning w2v2, feature extraction for the entire ASVspoof 2019 LA dataset takes 40 min, and final decision-making using XGBoost requires an additional 3 min. All experiments, except those involving frequency band analysis, were repeated five times, and the mean and standard deviation were subsequently computed. We additionally note that the model’s final training performance on EER was consistently 0%, so we mainly report Dev and Eval EER.

iWAX evaluation

We conducted experiments corresponding to the feature selection step. As shown in Table 1, XGBoost achieved an evaluation EER of 0.3136% at the time point of \(\frac{2}{4}\) and 0.3141% at \(\frac{3}{4}\). Additionally, we performed a re-evaluation based on the methodology proposed by Kang et al.19, and obtained an evaluation EER of 0.3975%. While Kang et al. showed outstanding performance on the development set, their model showed a slight drop in adaptability to the evaluation set. In contrast, our model maintained a balanced performance across both sets.

Our approach also outperformed the w2v2-AASIST counterpart on the evaluation set (Wilcoxon rank-sum test followed by Bonferroni correction, \(p < 0.05\)). Furthermore, compared to the method of Li et al.23, which focuses on marking salient segments of the audio, our model achieved better detection performance while providing interpretability in both temporal and frequency domains. Another notable observation is that the top three significant features identified through the XGBoost feature importance mechanism remained consistent. This stability across various audio extraction points enables feature-based interpretation. The three features, f85, f1000, and f1001 exhibited high F-scores as shown in Table 1, and we further analyze the corresponding audio time intervals.

iWAX interpretation

Temporal interpretation

The temporal importance extraction step was applied to further interpret the model’s behavior. From previous experiments, we identified that three features including f85, f1000, and f1001 play a significant role in voice spoofing detection. Accordingly, we used these features to construct three corresponding vectors spanning the entire temporal dimension, which served as inputs for the XGBoost countermeasure. The resulting evaluation EERs, ordered by feature importance (f1000, f1001, f85) at \(T=\frac{1}{4}, \frac{2}{4}\), were 0.3612%, 0.6388%, and 2.0992%, respectively, as shown in Table 2. The performance using f1000 was statistically significantly better than the other features, confirmed by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test followed by Bonferroni correction (\(p < 0.05\)). It is noteworthy that Fig. 5 visualizes the results from Tables 1 and 2 as bar plots, comparing Dev and Eval EER of XGBoost-based iWAX variants across three temporal sampling points (1/4, 2/4, 3/4) and three single-feature choices (f85, f1000, f1001).

Using XGBoost’s feature importance mechanism, we also investigated the specific temporal intervals that the model focuses on. Figure 3 describes the temporal importance across the full input sequence, as well as the average importance within 10 segmented intervals. Overall, the model predominantly attends to the beginning and middle portions of the audio samples. This tendency can be attributed to the preprocessing method, where audio clips shorter than the target length of 4 s are padded by repeating their initial segments to fill the gap. As such padding introduces unnatural discontinuities, the model appears to avoid these artificial regions and instead prioritizes continuous sections, primarily at the beginning and middle. This pattern was consistently observed across all three models, offering meaningful insight into which temporal regions are most critical for voice spoofing detection.

Frequency band-based interpretation

To enable frequency band-based interpretation of iWAX, we first apply a sinc filter to raw waveforms. By manually specifying low and high frequency cutoffs, we compare EER and feature importance across different frequency bands. We also examine whether f85, f1000, or f1001 appear within the top 30 features ranked by XGBoost, with the audio extraction point fixed at \(T=\frac{2}{4}\).

As described in Table 3, the frequency range between 0 and 128 Hz yielded a high evaluation EER of 13.9095%, and none of the three key features, f85, f1000, nor f1001, appeared in the top 30 features. When setting the lower frequency boundary to 64 or 128 Hz and progressively expanding the upper limit, the model achieved EER and feature importance values comparable to the baseline model that utilized the entire frequency spectrum.

From these experiments, we derive insights into the spectral focus of w2v2. The line graph in Fig. 6 illustrates the trend of model performance across different frequency ranges. First, the model tends to concentrate on the frequency range from 128 to 8000 Hz, indicating that the lower band between 0 and 128 Hz is less informative for voice spoofing detection. Second, selecting an appropriate frequency range can improve performance compared to using the full spectrum. For example, using the range from 128 to 8000 Hz resulted in an evaluation EER of 0.2883%, which is lower than the baseline model’s EER of 0.3136%. Notably, 14 of the top 30 features in this range overlapped with those of the baseline model, while the 64 to 8000 Hz range shared 16 features in common. Additionally, Fig. 4 presents the top 10 features identified by the XGBoost model for each time point and frequency band. Although the analysis was conducted using the top 30 features, only the top 10 are shown for clarity.

Discussion

iWAX addresses the interpretability challenge inherent in pre-trained large-scale deep learning models for voice spoofing detection by offering a novel interpretation approach that also enhances detection performance. The key innovation lies in leveraging XGBoost’s feature importance mechanism to analyze the temporal segments within audio samples that w2v2 prioritizes during spoofing detection. In addition, by applying sinc filters to raw waveforms, iWAX identifies specific frequency bands that w2v2 focuses on. This dual analysis of temporal and spectral features provides meaningful insight for a comprehensive interpretation of w2v2’s behavior and the role of specific speech features in its decision-making process.

Another strength of iWAX is its integration of w2v2, a model that extracts features directly from raw waveforms, thereby capturing a broader range of acoustic information compared to traditional feature extraction techniques such as mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCC) and linear prediction coefficients (LPC). As a self-supervised learning-based speech recognition model, w2v2 also maintains high performance with limited labeled data. By combining the features extracted by w2v2 with AASIST and XGBoost, the model performance can be further improved, particularly in capturing long-term speech patterns.

To further validate the framework, we conducted an ablation study using LightGBM33 classifier instead of XGBoost. LightGBM is a gradient boosting framework that employs histogram-based learning and a leaf-wise tree growth strategy. Like XGBoost, it offers a feature importance mechanism to evaluate the contribution of each feature to the model’s predictions. As shown in Table 4, LightGBM achieved slightly better performance than XGBoost and consistently highlighted the same top three features. This difference was found to be statistically significant based on a t-test, indicating the potential for further improvements through model selection and hyperparameter tuning. While XGBoost’s feature importance mechanism provides overall dataset understanding, it lacks the ability to capture instance-specific importance unlike interpretable models such as TabNet34 or SHAP35 and integrated attention visualization methods. Future work will focus on developing an enhanced interpretability framework capable of per-instance analysis. We would like to note that our work primarily focuses on analyzing the global tendencies of the model, since understanding the overall decision process and dataset-level tendency of voice spoofing detection was our first step. For future work, we plan to extend the analysis to the local level and employ various methods to enable comparison across different approaches.

Additionally, exploring a wider variety of filters for raw waveform transformation will support more diverse interpretations of w2v2 beyond frequency-based features. Ablation study on multi-feature combinations will also be necessary to better understand their individual and joint contributions. Further evaluation on diverse datasets including ASVspoof 2021 and WaveFake will be required to assess the generalization capability of the proposed approach. Moreover, while this work primarily focused on building an interpretable and effective framework, future research will explore parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods such as LoRA so that reduce the computational burden of the large model.

As another possible direction, future work will explore trainable filter banks to optimize frequency ranges beyond the manually defined, perceptually motivated bands. One more interesting extension is designing an end-to-end trainable framework, possibly in combination with tabular deep learning architectures, such as TabNet or FT-Transformer.

Full frequency-band inference yields an Eval EER of 0.3136%, which is much closer to that of 128-8000 Hz (0.2883%) than to 0-64 Hz (18.4083%) or 0-128 Hz (13.9095%), as shown in Table 3. This indicates that the iWAX decision process effectively discounts the least informative low-frequency band, which may act as noise, thereby contributing to more stable performance under potential degradations. We can also observe that same top features (f1000, f1001, f85) consistently dominate XGBoost’s feature importance. This stability suggests that our proposed model relies on robust and repeatedly selected cues rather than instance-specific artifacts. Taken together, subband-based design and stable feature selection choice of iWAX suggest robustness of the framework. For future work, we plan to validate our framework on noisy datasets or employ noise augmentation and reverberation simulation to validate resilience which could align with real-world deployment scenarios.

Prior research has also explored Visual Speech Recognition (VSR), showing that visual information alone can help mitigate voice spoofing36,37. If these visual features are combined with audio features, Audio-Visual Speech Recognition (AVSR) can be constructed. Building on this, integrating feature importance or attention maps from both audio and visual modalities could yield more meaningful and interpretable results.

Conclusion

iWAX presents a novel approach to voice spoofing detection by combining the strengths of wav2vec 2.0 and XGBoost. Traditional machine learning models are lightweight and offer some degree of interpretability, but are limited by the need for manually engineered features. In contrast, deep learning-based audio representations capture a wide range of acoustic characteristics, but often involve substantial computational resources and present challenges in interpretability. iWAX addresses these limitations by integrating wav2vec 2.0 with XGBoost, providing an interpretable and effective voice spoofing countermeasure. To further validate the robustness of our framework, we also conducted experiments using LightGBM as an alternative classifier, confirming consistent trends.

The primary contribution of this study lies in the integration of temporal and frequency-based feature analyses to enhance model interpretability. The temporal analysis identifies key features and the corresponding time intervals they influence. Meanwhile, the frequency-based analysis employs sinc filters applied to raw waveforms to concentrate on specific frequency bands. These dual perspectives enable iWAX to reveal which time segments and frequency bands the model emphasizes when making decisions. In terms of performance, iWAX outperforms both AASIST and w2v2-AASIST in terms of EER evaluation. Moreover, by selectively applying frequency band filtering, iWAX achieves improved performance compared to models trained on the full frequency spectrum. Overall, the proposed framework delivers a computationally efficient and interpretable model for voice spoofing detection, addressing key limitations of prior methods in this domain.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the ASVspoof 2019 LA repository, which can be found from Todisco, M. et al. (2019)32. The code and pretrained models used for iWAX are available at https://github.com/duneag2/iwax.

References

Villalba, J., Miguel, A., Ortega, A. & Lleida, E. Spoofing detection with dnn and one-class svm for the asvspoof 2015 challenge. Proc. Interspeech 2015, 2067–2071 (2015).

Chettri, B. & Sturm, B. L. A deeper look at gaussian mixture model based anti-spoofing systems. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). 5159–5163. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2018.8461467 (2018).

Tak, H., Patino, J., Nautsch, A., Evans, N. & Todisco, M. Spoofing attack detection using the non-linear fusion of sub-band classifiers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.10393 (2020).

Rahmeni, R., Aicha, A. B. & Ayed, Y. B. Voice spoofing detection based on acoustic and glottal flow features using conventional machine learning techniques. Multimed. Tools Appl. 81, 31443–31467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-12606-8 (2022).

Rahmeni, R., Aicha, A. B. & Ayed, Y. B. Acoustic features exploration and examination for voice spoofing counter measures with boosting machine learning techniques. Proc. Comput. Sci. 176, 1073–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2020.09.103 (2020). Knowledge-Based and Intelligent Information & Engineering Systems: Proceedings of the 24th International Conference KES2020.

Choi, S., Kwak, I.-Y. & Oh, S. Overlapped frequency-distributed network: Frequency-aware voice spoofing countermeasure. In Proc. Interspeech 2022. 3558–3562. https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2022-657 (2022).

Li, X., Wu, X., Lu, H., Liu, X. & Meng, H. Channel-wise gated res2net: Towards robust detection of synthetic speech attacks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.08803 (2021).

Ravanelli, M. & Bengio, Y. Speaker recognition from raw waveform with SincNet. In 2018 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT). 1021–1028. https://doi.org/10.1109/SLT.2018.8639585 (2018).

Jung, J.-W., Heo, H.-S., Kim, J.-H., Shim, H.-J. & Yu, H.-J. Rawnet: Advanced end-to-end deep neural network using raw waveforms for text-independent speaker verification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.08104 (2019).

Tak, H. et al. End-to-end anti-spoofing with rawnet2. ICASSP 6369–6373, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP39728.2021.9414234 (2021).

Jung, J.-W. et al. Aasist: Audio anti-spoofing using integrated spectro-temporal graph attention networks. In ICASSP 2022 - 2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). 6367–6371. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP43922.2022.9747766 (2022).

Baevski, A., Zhou, Y., Mohamed, A. & Auli, M. wav2vec 2.0: A framework for self-supervised learning of speech representations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 12449–12460 (2020).

Babu, A. et al. XLS-R: Self-supervised cross-lingual speech representation learning at scale. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2022. 2278–2282. https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2022-143 (2022).

Radford, A. et al. Robust speech recognition via large-scale weak supervision. In International Conference on Machine Learning. 28492–28518 (PMLR, 2023).

Chen, S. et al. Wavlm: Large-scale self-supervised pre-training for full stack speech processing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 16, 1505–1518 (2022).

Lee, J. W., Kim, E., Koo, J. & Lee, K. Representation selective self-distillation and wav2vec 2.0 Feature exploration for spoof-aware speaker verification. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2022. 2898–2902. https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2022-11460 (2022).

Tak, H. et al. Automatic speaker verification spoofing and deepfake detection using wav2vec 2.0 and data augmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.12233 (2022).

Tak, H. et al. Automatic speaker verification spoofing and deepfake detection using wav2vec 2.0 and data augmentation. In Proceedings of the Speaker and Language Recognition Workshop (Odyssey 2022). 112–119. https://doi.org/10.21437/Odyssey.2022-16 (2022).

Kang, T. et al. Experimental study: Enhancing voice spoofing detection models with wav2vec 2.0 (2024). arxiv:2402.17127.

Singla, Y. K., Shah, J., Chen, C. & Shah, R. R. What do audio transformers hear? Probing their representations for language delivery & structure. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW). 910–925. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDMW58026.2022.00120 (2022).

Grosz, T., Getman, Y., Al-Ghezi, R., Rouhe, A. & Kurimo, M. Investigating wav2vec2 context representations and the effects of fine-tuning, a case-study of a Finnish model. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2023. 196–200. https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2023-837 (2023).

tom Dieck, T., Pérez-Toro, P. A., Arias, T., Noeth, E. & Klumpp, P. Wav2vec behind the Scenes: How end2end models learn phonetics. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2022. 5130–5134. https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2022-10865 (2022).

Li, M. & Zhang, X.-P. Interpretable temporal class activation representation for audio spoofing detection. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2024. 1120–1124. https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2024-2156 (2024).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). 618–626. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2017.74 (2017).

Xu, K. et al. Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning (Bach, F. & Blei, D. Eds.). Vol. 37. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. 2048–2057 (PMLR, 2015).

Grinberg, P., Kumar, A., Koppisetti, S. & Bharaj, G. What does an audio deepfake detector focus on? A study in the time domain. In ICASSP 2025 - 2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP49660.2025.10887568 (2025).

Chhibber, M., Mishra, J., Shim, H.-J. & Kinnunen, T. H. An explainable probabilistic attribute embedding approach for spoofed speech characterization. In ICASSP 2025 - 2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP49660.2025.10889868 (2025).

Kwak, I.-Y. et al. Low-quality fake audio detection through frequency feature masking. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Deepfake Detection for Audio Multimedia, DDAM ’22. 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1145/3552466.3556533 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2022).

Salvi, D., Bestagini, P. & Tubaro, S. Towards frequency band explainability in synthetic speech detection. In 2023 31st European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO). 620–624. https://doi.org/10.23919/EUSIPCO58844.2023.10289804 (2023).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, KDD ’16. 785–794. https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. The impact of silence on speech anti-spoofing. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Proc. 31, 3374–3389. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASLP.2023.3306711 (2023).

Todisco, M. et al. Asvspoof 2019: Future horizons in spoofed and fake audio detection. In Proceedings Interspeech 2019. 1008–1012. https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2019-2249 (International Speech Communication Association, 2019). Interspeech 2019 ; conference date: 15-09-2019 through 19-09-2019.

Ke, G. et al. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS’17. 3149–3157 (Curran Associates Inc., 2017).

Arik, S. Ö. & Pfister, T. Tabnet: Attentive interpretable tabular learning. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 35, 6679–6687. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v35i8.16826 (2021).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS’17. 4768–4777 (Curran Associates Inc., 2017).

Chandrabanshi, V. & Domnic, S. A novel framework using 3D-cnn and bilstm model with dynamic learning rate scheduler for visual speech recognition. Signal Image Video Process. 18, 5433–5448 (2024).

Chandrabanshi, V. & Domnic, S. Leveraging 3D-cnn and graph neural network with attention mechanism for visual speech recognition. Signal Image Video Process. 19, 844 (2025).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00341075, RS-2023-00208284)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L., S.O.; methodology, S.L., S.C., S.O, I.K.; software, S.L.; validation, S.L., S.C., T.K., S.C., S.H., S.P.,E.K.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, S.L., S.C., T.K., S.C., S.H., S.P.,E.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing–review and editing, S.L., S.C., S.H., S.O., I.K.; visualization, S.L.; supervision, S.O., I.K.; funding acquisition, S.O., I.K.; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S., Choi, S., Kang, T. et al. iWAX: interpretable Wav2vec-AASIST-XGBoost framework for voice spoofing detection. Sci Rep 15, 40491 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24361-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24361-5