Abstract

Staphylococcus pseudintermedius is an important opportunistic pathogen of companion animals, mainly associated with skin and mucous membrane colonization among pets. We aimed to characterize the S. pseudintermedius isolates collected from dogs and cats nationwide in South Korea. A total of 1,071 S. pseudintermedius isolates were recovered from mostly dogs (n = 1037) and cats (n = 34) in four different infection sites: skin/ear (n = 887), urine (n = 28), respiratory tract (n = 49), and genital organs (n = 107). S. pseudintermedius isolates exhibited high resistance (> 50%) to penicillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and chloramphenicol. Antimicrobial resistance rates were significantly higher in non-skin isolates than in skin isolates from dogs (p < 0.05). In addition, the isolates demonstrated higher resistance to most antimicrobials in dogs of older ages. Multidrug resistance was detected in more than 70% of isolates. The methicillin resistance was detected in 35.1% of S. pseudintermedius. Furthermore, the methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius (MRSP) isolates showed significantly higher resistance to non-beta-lactam antimicrobials than the methicillin-sensitive S. pseudintermedius (MSSP) isolates (p < 0.05). Multi-locus sequence typing revealed the presence of 48 sequence types (STs) in 100 MRSPs, of which 24 types were identified newly in this study. The most frequently detected STs were ST121, ST794, ST1328, ST71, and ST496, comprising 33.3%. pRE25-like elements, including rec, IS1252, and IS1216, were identified in 62% of MRSP, commonly showing resistance to chloramphenicol. Moreover, the pRE25-like elements were associated with STs, with five predominantly detected STs carrying pRE25-like elements, except for ST71. The occurrence of methicillin resistance among S. pseudintermedius with predominant STs and pRE25-like elements in dogs and cats potentially poses health hazards to humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Staphylococcus pseudintermedius is an opportunistic bacterium localized in the skin and mucous membranes of companion animals. It is associated with over 80% of pyoderma infections, particularly in dogs1 and, to a lesser extent, in cats2. S. pseudintermedius is also connected with postoperative wounds, eyes, and skin infections and is a significant cause of disease of the urinary tract, respiratory system, and other body tissues3. In the past decades, S. pseudintermedius has been isolated from dogs across Europe and North America at increasing frequencies and occasionally from cats and horses4,5,6.

S. pseudintermedius resistance to the varying classes of antimicrobials is emerging as a severe problem in veterinary practice. Recently, S. pseudintermedius isolated from companion animals has seen increased resistance to various antimicrobials, including beta-lactams, macrolides, and fluoroquinolones, observed in different countries7,8. The epidemiology and molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius (MRSP) isolated from companion animals have been investigated worldwide9,10. Moreover, the clonal dissemination of MRSP in companion animals has been reported in many countries, including Malaysia11, Italy12, and Brazil13.

pRE25-like elements, characterized as mobile genetic elements, impart resistance to multiple antimicrobials in S. pseudintermedius14. Several investigations have described multidrug-resistant pRE25-like elements contributing to the spreading of resistance genes in methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius15,16. Moreover, these elements could be disseminated from companion animals to humans16. The presence of these elements leading to multidrug resistance may restrict treatment options for MRSP infections.

In Korea, several studies have been conducted to identify patterns of clonal spread, their genetic lineage, and gene sharing among different geographical areas17,18,19. However, reported studies on the prevalence and clonal dissemination were paucity in knowledge, such as targeting one or two infection sites, collecting samples from only one hospital or a specific region, and tracing genetic lineages concerning their geographical incidences. Thus, for the first time, we aimed to conduct a systematic investigation regarding S. pseudintermedius prevalence in different infection sites of dogs and cats and to investigate the antimicrobial resistance and evidence of the clonal expansion of MRSP lineages nationwide in South Korea. Moreover, we also assessed the presence of pRE25-like elements in methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius.

Results

Distribution of S. pseudintermedius

A total of 1,071 (26.9%) S. pseudintermedius isolates were recovered from 3972 samples during 2018–2019 (Table 1). Among the samples, S. pseudintermedius isolates were frequently recovered from skin/ear (30.1%, 887/2949), followed by genital organ (22.5%, 107/476), respiratory system (16.1%, 49/305), and urine (11.6%, 28/242).

Antimicrobial resistance

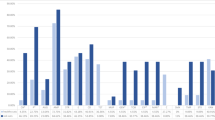

Overall, a majority of the S. pseudintermedius isolates (53.8–78.5%) showed resistance to penicillin (78.5%), followed by erythromycin (67%), clindamycin (63.4%), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (57.6%), and chloramphenicol (53.8%) (Fig. 1). No or rare (less than 1%) resistance was observed for amikacin, linezolid, rifampin, and vancomycin. Antimicrobial resistances were diverse among different origin sites, with significant variation in some antimicrobial resistance rates (Fig. 1). In dogs, chloramphenicol (52.5% vs. 61.8%), erythromycin (65.9% vs. 74.6%), and penicillin (75.9% vs. 90.2%) were significantly higher in non-skin isolates than in isolates recovered from the skin (p < 0.05; Fig. 1a). In cats, the resistance rates (> 50%) of erythromycin, penicillin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole were found in the majority of the isolates (Fig. 1b). However, only the ceftiofur resistance rate was significantly higher in non-skin isolates compared to skin isolates (p < 0.05).

Antimicrobial resistance profile of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from dogs (a) and cats (b) during 2018–2019 in South Korea. *p < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant change in antimicrobial resistance rate between skin and non-skin isolates. AMK, amikacin; AMP, ampicillin; CFZ, cefazolin; CHL, chloramphenicol; CLI, clindamycin; CPD, cefpodoxime; ENO, enrofloxacin; ERY, erythromycin; GEN, gentamicin; LNZ, linezolid; MAR, marbofloxacin; OXA, oxacillin; PEN, penicillin; RIF, rifampin; SXT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; VAN, vancomycin; VEC, cefovecin; XNL, ceftiofur. MDR, multidrug resistance.

The S. pseudintermedius isolates obtained from dogs and cats exhibited different levels of antimicrobial resistance depending on the age of their hosts. The isolates from dogs aged > 15 years demonstrated higher resistance to most antimicrobials (Table 2). Of note, resistance to beta-lactams was higher in the older age group. Resistance to ampicillin (66.7%), cefovecin (48.1%), ceftiofur (48.1%), and oxacillin (55.6%) was significantly greater in aged > 15 years compared to the other age groups (aged < 1 year and 1–5 years). In cats, most of the isolates recovered from aged < 1 year exhibited a greater rate of antimicrobial resistance compared to isolates from older age groups (aged 1–5 years and 6–10 years). However, a higher level of resistance was observed towards cefazolin (33.3%), cefpodoxime (33.3%), chloramphenicol (66.7%), penicillin (100%), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (66.7%) in isolates from aged 6–10 years than those isolates from other age groups, although there was no significant difference in any combination.

Multidrug resistance (MDR) and antimicrobial resistance patterns

MDR isolates were defined when they showed resistance against three or more classes of antimicrobial agents20. It was found that 91.5% of the isolates were resistant to at least one antimicrobial agent. Moreover, a total of 75.6% of the dog isolates and 70.6% of the cat isolates showed MDR (Fig. 1; Table 3). Resistance to one to four antimicrobials was detected in 29.5% of isolates. Furthermore, 188 (17.6%) isolates demonstrated resistance to ten or more antimicrobials. A total of 130 MDR combination patterns were observed in the collected isolates (Supplementary Table S1). Among them, most of the resistant patterns included penicillin.

Occurrence of methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius

Methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius (MRSP) was found in 35.1% (376/1071) of the isolates from both dogs (34.8%, 361/1037) and cats (44.1%, 15/34) (Table 2). Notably, dogs aged > 15 years had higher levels of MRSP compared to other age groups. In the sample levels, the occurrence of MRSP was not significantly different between skin and non-skin samples from dogs and cats. The resistance rates of MRSP (n = 376) and MSSP (n = 695) against 18 antimicrobials are illustrated in Fig. 2. We have observed that MRSP isolates showed significantly higher resistance against beta-lactam as well as non-beta-lactam antimicrobials compared to MSSP isolates. In particular, resistance to clindamycin (71.5% vs. 59%), fluoroquinolones (enrofloxacin, 60.6% vs. 20.6% and marbofloxacin, 62% vs. 20.4%), erythromycin (76.9% vs. 61.7%), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (70.7% vs. 50.5%) were also significantly higher in MRSP isolates than in MSSP (p < 0.05).

Antimicrobial resistance rate of methicillin-resistant (MRSP) and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MSSP) isolated from dogs and cats during 2018–2019 in South Korea. *p < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant change in antimicrobial resistance rate between MRSP and MSSP isolates. AMK, amikacin; AMP, ampicillin; CFZ, cefazolin; CHL, chloramphenicol; CLI, clindamycin; CPD, cefpodoxime; ENO, enrofloxacin; ERY, erythromycin; GEN, gentamicin; LNZ, linezolid; MAR, marbofloxacin; OXA, oxacillin; PEN, penicillin; RIF, rifampin; SXT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; VAN, vancomycin; VEC, cefovecin; XNL, ceftiofur. MDR, multidrug resistance.

Multi-locus sequence typing of methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius

Among the 376 MRSPs, we selected 100 multidrug-resistant MRSP isolates comprising dogs (98 isolates) and cats (2 isolates) that exhibited co-resistance to clindamycin, erythromycin, and enrofloxacin (Fig. 3; Tables 2 and 4). A total of 48 STs were detected in 100 MRSPs. Among them, five predominant types were ST121 and ST794, followed by ST1328, ST71, and ST496, comprising 33.3% (33/100). However, 27 STs were found to represent only a single isolate each (Fig. 3; Table 4). Moreover, the analysis of ST prevalence in different regions of South Korea showed the most common MRSP STs with representatives from the A and F regions. In the genetic relationship of MRSPs, we found that 33 of the 48 STs were related to each other and formed clonal complexes, while 14 STs were singletons and did not make clonal complexes, accounting for 29.2% of all identified STs (Fig. 3). Moreover, among the identified STs, some STs (ST1328 and ST121) were the primary founders, surrounded by 6 SLVs (single-locus variants) and DLVs (double-locus variants).

Clonal distribution of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in different provinces. A single eBURST diagram shows S. pseudintermedius ST in the same shade, representing the same clonal complex (CC) clusters by setting a group founder marked with an asterisk that links the STs at four or more loci. The locus variants are indicated by different numerals (1, 2, 3, or 4) above connected lines between STs.

Analysis of pRE25-like element

We found three pRE25-like elements (rec, IS1252, and IS1216) in this investigation (Table 4). Of the 100 MRSP isolates, 62 (62%) were positive for pRE25-like elements, while the remaining 38 MRSPs did not contain pRE25-like elements. There was an association of pRE25-like carrying elements with MLST. Among the 48 STs, 29 STs carried pRE25-like elements. Interestingly, four dominant STs (ST121, ST794, ST1328, and ST496) carried the pRE25-like elements. However, of the 48 STs, a total of 19 ST clusters tested negative for PRE25-like components. Moreover, among the multiple resistances, all isolates carrying pRE25-like elements were resistant to chloramphenicol.

Discussion

In the present report, for the first time, we investigated the prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of S. pseudintermedius in dogs and cats at the national level in South Korea. We also analyzed the variety of genotypes and the presence of pRE25-like elements. Our findings showed that S. pseudintermedius exhibited significant resistance to methicillin and other multiple antimicrobials, along with the emergence of various clonal lineages distributed in different provinces.

In this investigation, different proportions of S. pseudintermedius isolates were recovered from companion animals, mostly dogs rather than cats. Moreover, the prevalence of S. pseudintermedius varied in the sample levels, with the majority found in the skin/ear, followed by the genital organ, respiratory system, and urine samples. The findings of our study align with prior reports, indicating that dogs are the primary source of S. pseudintermedius21. The incidence of S. pseudintermedius infection in companion animals has been increasing, associated with several risk factors, such as misuse and/or abuse of antimicrobials for treatment, long-term hospitalization, surgery, and contact with infected companion animals in recent years22.

Moreover, skin/ear are the most common infection sites of S. pseudintermedius in companion animals23. Studies conducted on the prevalence of S. pseudintermedius in dogs with skin and otitis externa symptoms are also in common with our findings from Brazil24 and China25. However, the occurrence of S. pseudintermedius isolates in the skin in our investigation was less than that stated by the studies from the USA (45.6%)26, South Africa (58.8%)27, and Finland (77%)28. The frequency of recovered isolates from the genital organ, respiratory organ, and urine samples was higher than that reported by the study from Grönthal et al.6 in Finland. This discrepancy in the occurrence of isolates might be due to variations in regional distribution, the presence or absence of disease, the sampling site, and the testing method29.

S. pseudintermedius isolates recovered from companion animals have frequently demonstrated resistance to several antimicrobials, including β-lactams and non-β-lactams. Concurring with prior studies in Canada30, Poland31, and Argentina32, a significant proportion of S. pseudintermedius obtained from dogs and cats showed resistance to penicillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Several previous investigations have detected variable resistance rates (17–90%) to these antimicrobials in S. pseudintermedius isolated from dogs and cats28,33,34. Our studies revealed consistent findings, indicating that 53.8–78.5% of the S. pseudintermedius obtained from dogs and cats exhibited resistance to these antimicrobials. Moreover, the overall resistance rate of the tested antimicrobials was higher in dog isolates than in cats, a disparity that could be attributed to a greater prevalence of sampling within the dog population. Dogs are more prone to bacterial infections than cats, usually with S. pseudintermedius, especially in conditions like pyoderma, and are likely to receive more antimicrobials, leading to the development of higher resistance in dogs than in cats35. Similar other prior studies have documented the notable difference36,37.

Antimicrobial resistance of the isolates showed variation among the different sites of origin. Our findings showed that resistance to most of the antimicrobials, including chloramphenicol, erythromycin, and penicillin, was significantly higher in dog non-skin isolates compared to skin isolates. These findings were inconsistent with those of Grönthal et al.6, who reported that skin isolates from dogs showed significant resistance to these antimicrobials. Among cats, the majority of isolates (> 50%) showed resistance to erythromycin, penicillin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. The resistance of the S. pseudintermedius isolates obtained from cats to these antimicrobials is consistent with the previous studies in different geographical locations7,31. The higher incidence of antimicrobial resistance might be due to the frequent use of antimicrobials in companion animals38,39.

In this study, we evaluated the occurrence of antimicrobial-resistant S. pseudintermedius in dogs and cats in different age groups, considering that age has a significant role in the prevalence of bacterial infection and the emergence of antimicrobial resistance40. Resistance to ampicillin, cefovecin, ceftiofur, and oxacillin was significantly higher in the isolates from dogs aged > 15 years compared to the other age groups (aged < 1 year and 1–5 years). Similarly, a comparatively higher level of resistance was observed to cefazolin, cefpodoxime, chloramphenicol, penicillin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in isolates from the comparatively older age group (aged 6–10 years) of cats. However, the strains obtained from aged < 1 year cats exhibited relatively higher resistance to other tested antimicrobials, including fluoroquinolones and macrolides, than other age groups. It is speculated that animals are more vulnerable to bacterial infection at an early age, which triggers the increased intake of antimicrobials for treatment, resulting in a higher prevalence of resistant bacteria41. Moreover, consistent with the previous research, our study found a higher occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in isolates obtained from older companion animals42. Increased antimicrobial resistance rates in the isolates from companion animals might be due to their exposure to more antimicrobials throughout their lifetime43. However, previous studies revealed inconsistent antimicrobial resistance dynamics in isolates recovered from animals of different ages44.

In this investigation, we found MDR phenotype in more than 70% of S. pseudintermedius isolates recovered from both dogs and cats. This was much higher than that of the previous studies conducted in Finland (17%)28 and Spain (43.3%)33 on companion animals. We observed diverse MDR patterns; the most common resistance patterns included penicillin. It was reported that MDR patterns frequently include resistance to this antimicrobial45. Moreover, the veterinary guidelines recommend penicillin, which belongs to the class of β-lactam antimicrobials often used for systemic antimicrobial therapy in canine infections46. The strong selective pressure of antimicrobials may trigger the increase in the prevalence of MDR S. pseudintermedius in Korean companion animals47. Hence, the emergence and dissemination of MDR S. pseudintermedius in canines and felines are of growing concern, limiting treatment options and complicating efforts to control resistance48.

We found that S. pseudintermedius isolates from dogs (34.8%) and cats (44.1%) showed resistance to methicillin. Moreover, MRSP isolates also exhibited high resistance to multiple antimicrobials, including β-lactam and non-β-lactam antimicrobials. The prevalence of canine pyoderma associated with MRSP was reported in Italy (31.6%), which is consistent with the findings of this study12. Furthermore, concurring with this investigation, it was observed that the prevalence of MRSP isolates was significantly higher in clinical cases of canine and feline pyoderma compared to MSSP isolates49.

The MRSP isolates demonstrated increased resistance to fluoroquinolones and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, which aligns with the reports worldwide7,13,50. However, the fluoroquinolones (> 60%) and clindamycin (71.5%) resistance rates are still higher than those reported in Germany (fluoroquinolones, 23.3%; clindamycin, 0%)51. Nonetheless, the resistance rates of these antimicrobials are lower than those reported by the study in Australia (66–91.6%)52. Multiple studies have revealed that selection pressure exerted by using other antimicrobials acts as a risk factor for the prevalence of MRSP1,53. Moreover, the presence of the MRSP reservoir in companion animals is concerning because they could potentially contribute to the spread of MRSP to humans and other animals24.

In this study, we found a total of 48 STs in 100 MRSPs, with the most prevalent types being ST121 and ST794, followed by ST1328, ST71, and ST496, distributed in different provinces. Previous studies conducted in Sri Lanka54 and South Korea15 described the predominant prevalence of ST121 and ST794 in MRSP isolated from companion animals. Moreover, the genetic studies of S. pseudintermedius reported that ST71 is predominant in Europe55 and ST296 in Australia56. In addition, consistent with previous investigations, our studies demonstrated that various genetic lineages, including ST71, ST76, ST121, ST361, ST370, ST566, ST568, and ST809, have been identified in South Korea17,18,19,57. It was shown that among the detected predominant STs, ST71 is of prime importance for MDR7. Papić et al.58 reported that various MDR incidences are mainly related to clonal transmission by ST71.

However, specific STs were observed in particular provinces in the present study: ST71 was detected only in A and F. Moreover, more than five region-specific STs were detected in F, A, C, G, and B. Together with our findings, we suggested that the resistance of S. pseudintermedius has been spreading worldwide and within different provinces of South Korea due to the expansion and dissemination of specific lineages with similar genetic backgrounds and the increased mobility of animals and people across topographical borders. Regarding the genetic relations of MRSPs, our current findings were in line with those reports from different countries13,59,60 and previously reported STs from South Korea18. Moreover, the dissemination of MRSP CC121, CC566, and CC1328 among companion animals in different countries has been reported, which is consistent with our investigation15,54.

In our results, we identified some genetic lineages, such as ST124, ST1328, ST1394, and ST1609, that formed clonal complexes with already identified STs. On the other hand, some other identified STs, including ST1604, ST1605, ST1607, ST1612, ST1614, ST1616, ST1617, ST2077, ST2078, ST2079, ST2082, and ST2083, did not form clonal complexes with previously identified STs and are genetically distinct from previously reported STs by other countries and South Korea, attributed as locally evolved new clones17,18,19,57.

The pRE25-like elements significantly contribute to the antimicrobial resistance in pathogenic bacteria14. In this study, a significant proportion of multidrug-resistant MRSP isolates were positive for all pRE25-like elements, which include rec, IS1252, and IS1216. It was investigated that the multidrug resistance pRE25-like element rec was frequently detected in S. pseudintermedius isolated from canine pyoderma15. The IS1252, a mobile genetic element, was often detected in staphylococci isolated from companion animals, significantly contributing to the spread of antimicrobial resistance61,62. Another transposable element, IS1216, frequently detected in S. pseudintermedius strains isolated from dogs and cats, demonstrated its presence in combination with other resistance genes such as erm(B) (gene for macrolide) and aac(6’)-aph(2’’) (gene for aminoglycoside), contributing to the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance63,64.

In addition, most of the STs proved to include pRE25-like elements contributing to the range of diversity in S. pseudintermedius14. Moreover, these transposable elements reinforce their potential to be clonally disseminated to humans and animals65. The STs of S. pseudintermedius containing pRE25-like components were detected, with a total of 29 STs. Furthermore, four predominant STs carried the pRE25-like elements. A previous study showed that the predominant number of STs were associated with the pRE25 group in S. pseudintermedius isolated from dogs suffering from pyoderma15. In addition, all MRSP isolates exhibited resistance to various other antimicrobials. Among them, chloramphenicol resistance was present in all isolates containing pRE25-like components, consistent with a previous investigation conducted in South Korea15.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings suggest that S. pseudintermedius has emerged as and continues to be an important canine and feline pathogen, not only limited to skin or skin infections but also distributed at various other sites in dogs and cats as an opportunistic pathogenic bacterium. Furthermore, this facultative pathogenic bacterium showed high resistance to methicillin and other commonly used antimicrobials, including penicillin, erythromycin, and clindamycin. Several MRSP clones were distributed nationwide in different provinces of South Korea. Moreover, the MRSP produced numerous clonal lineages (ST124, ST1328, ST1394, and ST1609) and pRE25-like elements (rec, IS1252, and IS1216), leading to severe problems for clinical therapeutics to treat infections. This study highlights the importance of current and future efforts to prevent and control infections and reduce the risk of methicillin resistance in S. pseudintermedius in humans and other animals. Thus, continuous supervision, monitoring, and the careful use of antimicrobials are necessary to prevent methicillin and other antimicrobial resistance in S. pseudintermedius.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Samples were collected between 2018 and 2019 from dogs and cats at 259 veterinary hospitals in seven metropolitan cities in South Korea. Swabs were collected from the skin/ear, urine, and genital organs of dogs and cats suspected of bacterial infection. The respiratory samples were obtained using rhinoscopy. A total of 3972 samples from dogs (2634 skin/ears, 172 urine, 150 respiratory systems, and 451 genital organs) and cats (315 skin/ears, 70 urine, 155 respiratory systems, and 25 genital organs) were collected (Table 1). All of the dogs and cats were house pets. Collected swab samples were placed in ice-cooled containers and immediately transported to the seven laboratories/centers participating in the Korean Veterinary Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System. The isolates obtained from various veterinary hospitals located in different provinces are displayed in Supplementary Fig. S1. However, we do not have information regarding the antimicrobial usage history in dogs and cats considered for this study.

Isolation and identification of species

The S. pseudintermedius strains were isolated and identified from dog and cat samples using the previously described method66. Briefly, swab samples were streaked on blood agar (Synergy Innovation, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea) and incubated aerobically for 16–20 h at 37 °C. The presumptive identification of S. pseudintermedius was based on colony morphology and color on the blood agar plate. In order to exclude the contaminant samples, only 1–2 major colonies showing morphological differences on one culture plate were selected for further analysis. The suspected colonies were further confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers (forward, F: TRGGCAGTAGGATTCGTTAA and reverse, R: CTTTTGTGCTYCMTTTTGG)67 and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF; Bruker Corporation, MA, USA). Briley, bacterial colonies were grown on the blood agar plate overnight at 37 °C. A small quantity of colony biomass was spread across the target sites on the MALDI plate. A 1 µL of matrix solution comprising alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid was applied to each sample spot and subsequently air-dried to promote matrix-sample co-crystallization. The prepared MALDI plate was positioned in the linear scanning mode of the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer. The plate was read, and the findings were compared with the database, delineating the distinctive spectrum of particular bacteria. One isolate per animal was used, and isolates from the same animal were not considered in our study.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was carried out by the broth microdilution method using the commercially available COMPGP1F Sensititre plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA)42. The isolates were tested for susceptibility toward 18 antimicrobials of different classes (aminoglycosides: amikacin and gentamicin; aminopenicillin: ampicillin; ansamycins: rifampicin; cephalosporins: cefazolin, cefovecin, cefpodoxime, and ceftiofur; folate pathway inhibitors: trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; glycopeptides: vancomycin; lincosamides: clindamycin; macrolides: erythromycin; oxazolidinones: linezolid; penicillins: oxacillin and penicillin: phenicols: chloramphenicol; and quinolones: enrofloxacin and marbofloxacin) (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). Methicillin-resistant isolates were detected based on resistance to oxacillin (CLSI, 2020)68. S. aureus ATCC 29,213 was used as a quality control strain. All antimicrobial resistance was interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (VET-01 S, M100)68. The results were within the CLSI quality control strain ranges, and the isolates were categorized as resistant and susceptible.

Detection of pRE25-like elements

The presence of pRE25-like elements was assessed by PCR using the previously described method and primers15: rec, F: GAAATATGGATATGCACGTGTC and R: GTACTGCGACTGAAACCG; IS1252, F: GAAACATCGTCTTGCCAAAG and R: CCAATTAGAGAATTCTTTCCCAC; IS1216, F: GATTATTGTAGCCGTGGGC and R: CCTTTAATCGTGGTAGAGGC. The PCR was performed based on the following conditions: enzyme activation and initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles of amplification at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 58 °C for 30 s. The PCR products were sequenced to determine the amplified genes using the ABI3730XL system (SolGent, Daejeon, South Korea). The DNA was extracted using a mini DNA extraction kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH, Duren, Germany).

Multi-locus sequence typing analysis

S. pseudintermedius genetic diversity was determined by multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) following the previous method69. A total of seven target genes (tuf, cpn60, pta, purA, fdh, ack, and sar) were amplified and sequenced. Gene sequencing was conducted using an ABI Prism 3730 analyzer (Solgent, Daejeon, South Korea). The inferred sequence of each target gene was compared with known sequences from the PubMLST database (http://pubmlst.org/spseudintermedius). An isolate with a novel combination of alleles was assigned a new ST number by the database curator (vincent.perreten@vetsuisse.unibe.ch). The STs of the S. pseudintermedius isolates were grouped using PHYLOViZ 2.0 and examined for associations with existing STs previously reported in the MLST database.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the data using Excel (Microsoft Excel, 2016, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and Rex Software (Version 3.0.3, RexSoft Inc., Seoul, South Korea). The antimicrobial resistance rates were determined using the chi-square test, where p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis for multiple comparisons among the different age groups of dogs and cats was performed using the R statistical software package (version 4.5.1)70. For each antimicrobial resistance in dog isolates, age-group differences were tested with an omnibus Pearson χ², followed by 2 × 2 Fisher’s exact pairwise comparisons with Holm’s multiplicity control, while in cats, age-group differences were tested with an omnibus Fisher’s exact and Fisher’s pairwise tests with Holm’s adjustment.

Limitation and future perspective

It should be mentioned that there are some limitations in this investigation. The quantity of S. pseudintermedius isolates obtained from dogs (n = 1037) was much higher than that from cats (n = 34), making it challenging to compare the results between the two groups. Moreover, the lack of available antimicrobial usage history data for the animals considered in this study exposes them to a reporting bias that should be cautiously taken into account in future investigations. Moreover, experiments on determining β-lactamase (ESBL/AmpC) genes warrant to be performed. Furthermore, the whole-genome sequencing needs to be accomplished for efficient comparison of the genetic characteristics of the isolates, including their clonal lineage.

Data availability

The data produced in this study are included within the article and its supplementary material.

References

Frosini, S. et al. Effect of topical antimicrobial therapy and household cleaning on meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius carriage in dogs. Vet. Rec. 190 (2022).

Weese, J. S. & Prescott, J. F. Staphylococcal infections. Greene’s Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat 611–626 (Elsevier, 2021).

Roberts, E. et al. Not just in man’s best friend: A review of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius host range and human zoonosis. Res. Vet. Sci. 105305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2024.105305 (2024).

Webster, A. E. The epidemiology of canine Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in Atlantic Canada. Doctoral dissertation, University of Prince Edward Island (2021).

Ruzauskas, M. et al. Characterization of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from diseased dogs in Lithuania. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. (2016).

Grönthal, T. et al. Epidemiology of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in guide dogs in Finland. Acta Vet. Scand. 57, 37 (2015).

Morais, C. et al. Genetic diversity and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius associated with skin and soft-tissue infections in companion animals in Lisbon, Portugal. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1167834 (2023).

Bellato, A. et al. Resistance to critical important antibacterials in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius strains of veterinary origin. Antibiotics 11, 1758 (2022).

Rynhoud, H. et al. Molecular epidemiology of clinical and colonizing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus isolates in companion animals. Front. Vet. Sci. 8, 620491 (2021).

Ma, G. C., Worthing, K. A., Gottlieb, T., Ward, M. P. & Norris, J. M. Molecular characterization of community-associated methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus from pet dogs. Zoonoses Public. Health. 67, 222–230 (2020).

Afshar, M. F., Zakaria, Z., Cheng, C. H. & Ahmad, N. I. Prevalence and multidrug-resistant profile of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in dogs, cats, and pet owners in Malaysia. Vet. World. 16, 536 (2023).

Menandro, M. L. et al. Prevalence and characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius from symptomatic companion animals in Northern italy: clonal diversity and novel sequence types. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 66, 101331 (2019).

Teixeira, I. M. et al. Investigation of antimicrobial susceptibility and genetic diversity among Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from dogs in Rio de Janeiro. Sci. Rep. 13, 20219 (2023).

Wegener, A. et al. Absence of host-specific genes in canine and human Staphylococcus pseudintermedius as inferred from comparative genomics. Antibiotics 10, 854 (2021).

Kang, J. H. & Hwang, C. Y. First detection of multiresistance pRE25-like elements from Enterococcus spp. In Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from canine pyoderma. J. Glob Antimicrob. Resist. 20, 304–308 (2020).

Wegener, A. C. H. Genomic dynamics of antimicrobial resistance in canine and human derived Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. Doctoral dissertation, Utrecht University, the Netherlands (2022).

Lee, G. Y. & Yang, S. J. Comparative assessment of genotypic and phenotypic correlates of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius strains isolated from dogs with otitis externa and healthy dogs. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 70, 101376 (2020).

Kang, J. H., Chung, T. H. & Hwang, C. Y. Clonal distribution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolates from skin infection of dogs in Korea. Vet. Microbiol. 210, 32–37 (2017).

Han, J. I., Rhim, H., Yang, C. H. & Park, H. M. Molecular characteristics of new clonal complexes of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius from clinically normal dogs. Vet. Q. 38, 14–20 (2018).

Magiorakos, A. P. et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 268–281 (2012).

Chrobak-Chmiel, D. et al. Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, both commensal and pathogen. Med. Weter. 74, 362–370 (2018).

Ruiz-Ripa, L. et al. S. pseudintermedius and S. aureus lineages with transmission ability circulate as causative agents of infections in pets for years. BMC Vet. Res. 17, 1–10 (2021).

Szewczuk, M. A., Zych, S. & Sablik, P. Participation and drug resistance of coagulase-positive Staphylococci isolated from cases of pyoderma and otitis externa in dogs. Slov. Vet. Res. Vet. Zb 57 (2020).

Guimarães, L. et al. Epidemiologic case investigation on the zoonotic transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius among dogs and their owners. J. Infect. Public. Health. 16, 183–189 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation, and virulence factors of isolates of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius from healthy dogs and dogs with keratitis. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 903633 (2022).

Tang, S. et al. The canine skin and ear microbiome: a comprehensive survey of pathogens implicated in canine skin and ear infections using a novel next-generation-sequencing-based assay. Vet. Microbiol. 247, 108764 (2020).

Qekwana, D. N., Oguttu, J. W. & Sithole, F. Burden and predictors of Staphylococcus aureus and S. pseudintermedius infections among dogs presented at an academic veterinary hospital in South Africa (2007–2012). PeerJ 5, e3198 (2017).

Grönthal, T. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and the molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius in small animals in Finland. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 2141 (2017).

Lynch, S. A. & Helbig, K. J. The complex diseases of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in canines: where to next? Vet. Sci. 8, 11 (2021).

Priyantha, R., Gaunt, M. C. & Rubin, J. E. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius colonizing healthy dogs in Saskatoon, Canada. Can. Vet. J. 57, 65 (2016).

Bierowiec, K. et al. Epidemiology of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in cats in Poland. Sci. Rep. 11, 18898 (2021).

Srednik, M. E. et al. Genomic features of antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from dogs with pyoderma in Argentina and the united states: A comparative study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 11361 (2023).

Viñes, J. et al. Concordance between antimicrobial resistance phenotype and genotype of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius from healthy dogs. Antibiotics 11, 1625 (2022).

Prior, C. D., Moodley, A., Karama, M., Malahlela, M. N. & Leisewitz, A. Prevalence of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolates from dogs with skin and ear infections in South Africa. J. S Afr. Vet. Assoc. 93, 40a–40 h (2022).

Bannoehr, J. & Guardabassi, L. Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in the dog: taxonomy, diagnostics, ecology, epidemiology and pathogenicity. Vet. Dermatol. 23, 253 (2012).

Gómez-Beltrán, D. A. et al. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in bacterial isolates from dogs and cats in a veterinary diagnostic laboratory in Colombia from 2016–2019. Vet. Sci. 7, 173 (2020).

Marco-Fuertes, A. et al. Multidrug-resistant commensal and infection-causing Staphylococcus spp. isolated from companion animals in the Valencia region. Vet. Sci. 11, 54 (2024).

Kim, S. M., Kim, H. S., Kim, J. W. & Min, K. D. Assessment of antimicrobial use for companion animals in South Korea: Developing defined daily doses and investigating veterinarians’ perception of AMR. Animals 15 (2025).

Weese, J. S. et al. Antimicrobial use guidelines for treatment of urinary tract disease in dogs and cats: Antimicrobial guidelines working group of the international society for companion animal infectious diseases. Vet. Med. Int. 2011, 263768 (2011).

Gandolfi-Decristophoris, P., Regula, G., Petrini, O., Zinsstag, J. & Schelling, E. Prevalence and risk factors for carriage of multi-drug resistant Staphylococci in healthy cats and dogs. J. Vet. Sci. 14, 449–456 (2013).

Moon, D. C. et al. Bacterial prevalence in skin, urine, diarrheal stool, and respiratory samples from dogs. Microorganisms 10, 1668 (2022).

Moon, B. Y. et al. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis isolated from healthy dogs and cats in South Korea. Microorganisms 11, 2991 (2023).

Caneschi, A., Bardhi, A., Barbarossa, A. & Zaghini, A. The use of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance in veterinary medicine, a complex phenomenon: a narrative review. Antibiotics 12, 487 (2023).

Moon, B. Y. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from healthy dogs and cats in South Korea, 2020–2022. Antibiotics 13, 27 (2023).

Videla, R. et al. Clonal complexes and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolates from dogs in the united States. Microb. Drug Resist. 24, 83–88 (2018).

Lee, C. H., Park, Y. K., Shin, S., Park, Y. H. & Park, K. T. Characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from dogs in veterinary hospitals in Korea. Int. J. Appl. Res. Vet. Med. 16 (2018).

Yoo, J. H., Yoon, J. W., Lee, S. Y. & Park, H. M. High prevalence of fluoroquinolone-and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolates from canine pyoderma and otitis externa in veterinary teaching hospital. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20, 798–802 (2010).

Haulisah, N. A., Hassan, L., Jajere, S. M., Ahmad, N. I. & Bejo, S. K. High prevalence of antimicrobial resistance and multidrug resistance among bacterial isolates from diseased pets: retrospective laboratory data (2015–2017). PLoS One. 17, e0277664 (2022).

Hensel, N., Zabel, S. & Hensel, P. Prior antibacterial drug exposure in dogs with meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP) pyoderma. Vet. Dermatol. 27, 72 (2016).

Jantorn, P. et al. Antibiotic resistance profile and biofilm production of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from dogs in Thailand. Pharmaceuticals 14, 592 (2021).

Feßler, A. T. et al. Antimicrobial and biocide resistance among feline and canine Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolates from diagnostic submissions. Antibiotics 11, 127 (2022).

Siak, M. et al. Characterization of meticillin-resistant and meticillin-susceptible isolates of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius from cases of canine pyoderma in Australia. J. Med. Microbiol. 63, 1228–1233 (2014).

Rana, E. A. et al. Prevalence of coagulase-positive methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in dogs in Bangladesh. Vet. Med. Sci. 8, 498–508 (2022).

Duim, B. et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius among dogs in the description of novel SCCmec variants. Vet. Microbiol. 213, 136–141 (2018).

Gagetti, P. et al. Identification and molecular epidemiology of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius strains isolated from canine clinical samples in Argentina. BMC Vet. Res. 15, 264 (2019).

Worthing, K. A. et al. Characterization of Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec elements from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius infections in Australian animals. mSphere 3, e00491–e00418 (2018).

Han, J. I., Yang, C. H. & Park, H. M. Prevalence and risk factors of Staphylococcus spp. Carriage among dogs and their owners: A cross-sectional study. Vet. J. 212, 15–21 (2016).

Papić, B., Golob, M., Zdovc, I., Kušar, D. & Avberšek, J. Genomic insights into the emergence and spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in veterinary clinics. Vet. Microbiol. 258, 109119 (2021).

Phumthanakorn, N. et al. Genomic insights into methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolates from dogs and humans of the same sequence types reveals diversity in prophages and pathogenicity Islands. PLoS One. 16, e0254382 (2021).

Gómez-Sanz, E., Torres, C., Lozano, C., Sáenz, Y. & Zarazaga, M. Detection and characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in healthy dogs in La Rioja, Spain. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 34, 447–453 (2011).

J., H. C. & M., H. R. IS26 and the IS26 family: versatile resistance gene movers and genome reorganizers. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 88, e00119–e00122 (2024).

MacFadyen, A. C. & Paterson, G. K. Methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius encoded within novel Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) variants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 79, 1303–1308 (2024).

Partridge, S. R., Kwong, S. M., Firth, N. & Jensen, S. O. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31, 10–1128 (2018).

Chanchaithong, P., Perreten, V. & Schwendener, S. Macrococcus canis contains recombinogenic methicillin resistance elements and the MecB plasmid found in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 74, 2531–2536 (2019).

Wegener, A. et al. Within-household transmission and bacterial diversity of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. Pathogens 11, 850 (2022).

Moon, D. C. et al. Prevalence of bacterial species in skin, urine, diarrheal stool, and respiratory samples in cats. Pathogens 11, 324 (2022).

Sasaki, T. et al. Multiplex-PCR method for species identification of coagulase-positive Staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 765–769 (2010).

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Seventh Informational Supplement, M100-S25 (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2020).

Solyman, S. M. et al. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51, 306–310 (2013).

Team, R. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2025).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the staff of the laboratories/centers participating in the Korean Veterinary Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System from 2018 to 2019.

Funding

This work was supported by the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency, Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs, Republic of Korea [Grant number: B-1543081-2024-26-01].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-J.K., D.C.M., and S.-K.L. conceived and designed the study. N.B., S.-J.K., B.-Y.M., J.-H.C., H.-J.S., and M.S.A. performed the experiments. J.-H.C. and N.B. analyzed and interpreted the data. S.-J.K., M.S.A., and N.B. wrote the original draft of the manuscript. M.S.A., B.-Y.M., D.C.M., N.B., J.-H.C., H.-J.S., S.-S.Y., J.-M.K., S.-C.P., and S.-K.L. revised and amended the manuscript. D.C.M. and S.-K.L. acquired funding and supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, SJ., Ali, M.S., Moon, BY. et al. Nationwide surveillance and molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from dogs and cats in South Korea. Sci Rep 15, 41190 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24385-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24385-x