Abstract

The automotive industry is moving towards low noise and lightweight, and acoustic metamaterials can play a vital role. This paper presents a new acoustic metamaterial consisting of cylindrical holes of different depths arranged circumferentially and divided into different cavities by spacers. The goal is to improve the acoustic absorption performance at low and medium frequencies (f ≤ 1100 Hz). The structure was simulated and studied using the finite element (FEM) simulation software COMSOL Multiphysics to analyze the noise reduction mechanism. Simulation analysis showed that the average sound absorption coefficient is greater than 0.90 in the 510 to 970 Hz frequency range. The acoustic absorption performance of the acoustic metamaterial designed in this paper is verified by using 3D printing to produce a model and an experimental study based on impedance tubes, and the FEM simulation and experimental curves are in good agreement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays, automotive NVH (Noise, Vibration, and Harshness) performance is a key factor in automotive comfort, and cars with low vibration and quietness have become the main pursuit of car buyers. For this reason, major automobile OEMs and component suppliers have invested huge human and material resources to improve their NVH performance continuously. With strict restrictions on sound-absorbing materials in the automotive field, it is difficult for existing technologies to meet the demand for thin-layer, low-frequency broadband acoustic materials in engineering practice. Currently, the traditional noise reduction program for the cockpit is mainly limited to improving conventional sound-absorbing materials and multi-layer traditional sound-absorbing materials superimposed on the cover1,2,3,4. This method is cumbersome and the sound absorption effect is limited. However, the excellent sound-absorbing properties of acoustic super-materials can play a vital role in reducing automobile noise in this regard. Therefore, studying acoustic metamaterials to realize low-frequency broadband sound absorption and sound insulation is a hot issue in current theoretical research and an urgent engineering problem. In the automotive field, where sound-absorbing materials are strictly restricted, existing technologies find it difficult to meet the demand for thin-layer, low-frequency broadband acoustic materials in engineering practice. Therefore, studying acoustic metamaterials to realize low-frequency broadband sound absorption and sound insulation is a hot issue in current theoretical research and an urgent engineering problem.

Domestic and foreign researchers have made numerous progress on acoustic materials, for national studies. Zhang et al.5 proposed a porous-lined coiled-structure acoustic metamaterial, established a theoretical model based on the double-porosity theory and the impedance transfer method, investigated the acoustic absorption performance of the metamaterial, and built a finite element simulation model to reveal its acoustic absorption mechanism. Gai et al.6 proposed a honeycomb-like sandwich acoustic metamaterial based on the properties of honeycomb structure, Helmholtz resonator, and acoustic metamaterial. Finite element models of the honeycomb structure and Helmholtz resonator unit were developed. Gao et al.7 proposed a composite porous metamaterial (CPM) consisting of a polyurethane sponge embedded in a multilayer I-plate to alleviate this problem. Sound absorption coefficients were calculated using the Johnson-Champoux - Allard model. Lu et al.8 tested the SAC of the FHCS using impedance tubes and simulated the structure using a virtual laboratory. The effects of different honeycomb sizes, fibred porosity, and filling amounts on the sound absorption coefficient of the structure were investigated. Wang et al.9 proposed a novel face-centered cubic core ultra-lightweight microporous sandwich structure acoustic material, which has excellent mechanical and acoustic properties. Xie et al.10 formed a new composite structure by filling the Nomex honeycomb with polyester fibers to improve its acoustic properties. Liu et al.11 constructed a new fractal acoustic metamaterial that enables sub-wavelength scale and broadband sound insulation. The finite element method and parametric inversion methods investigate the energy band structure, effective parameters, and transmission loss of acoustic metamaterials with different fractal orders. Sun et al.12 developed a hypersurface absorber for deep subwavelength thickness based on the Fabry-Perot resonance cavity. The impedance tube method was used to measure the absorption coefficient, and a continuous absorption spectrum in the range of 200 to 1600 Hz with an average absorption coefficient higher than 0.8 was realized under the condition of deep subwavelength thickness. Ruan H et al.13 proposed a new chiral helical structure based on the cochlear structure. Liu et al.14 proposed an ultra-broadband acoustic metamaterial with a thickness of only 7.2 cm, which can achieve near-perfect continuous absorption in the range of 380–3600 Hz. To solve the problem of poor low-frequency sound absorption efficiency and narrow bandwidth in traditional materials. In terms of foreign research. Zieliński et al.15 utilized defects in 3D printing to develop sound-absorbing materials. Vasina et al.16 investigated the acoustic absorption properties of open-cell acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene material structures prepared using 3D printing technology. The acoustic impedance tube transfer function method of a material’s normal absorption and noise reduction coefficient is measured by the acoustic impedance tube transfer function method. Rafique et al.17 proposed a composite structure of microporous plates consisting of non-uniform microporous plates and J-shaped cavities of different depths to improve the low-frequency (≤ 500 Hz) sound absorption performance of non-uniform microporous plates. Park et al.18 introduced a microporous plate absorber supported by a Helmholtz resonant cavity to improve sound absorption in the low-frequency region where conventional microporous plate absorbers do not provide adequate absorption. Melnikov et al.19 proposed an acoustic metamaterial structure to reduce noise pollution in multistage mechanical drive systems. Arjunan A et al.20 review focused on acoustic metamaterials, especially their critical properties and ineffective building sound insulation. A wide range of acoustic metamaterials that can complement traditional soundproofing methods for acoustically efficient building design are demonstrated. Gardiner et al.21 used stereolithography to design a functional superparamagnetic film with a resonance range of 88.73 to 86.63 Hz. Gardiner A et al.22 proposed a new concave bionic acoustic metamaterial with the aim of low-frequency vibration isolation and noise reduction, combined with the nesting pattern of a spider web. Chen A et al.23 proposed a composite acoustic metamaterial consisting of an array of Mie resonators and Helmholtz resonators that blocked more than 90% of the incident acoustic energy in the frequency range of 1250 Hz.

This study breaks the design paradigm of “consistent depth and uniform aperture” for cylindrical holes in traditional acoustic metamaterials, and adopts cylindrical cavities with stepped depth changes to expand the resonance frequency coverage through the depth difference, avoiding the limitation that a single-depth structure can only absorb sound at a specific frequency. The aperture is divided into three partitions to further broaden the sound absorption bandwidth through the combination of multi-size apertures, solving the core problem of “low efficiency and narrow bandwidth” of low-frequency sound absorption of traditional materials. The research program of this paper is as follows: Firstly, the theoretical basis of simulation and analysis of acoustic absorption materials is introduced. Next, simulation analysis and experimental verification are carried out, and the noise reduction mechanism is analyzed. Finally, the main conclusions and prospects for future work are given.

Materials and methods

Acoustic fundamental theory

In this paper, the sound absorption coefficient of the material was measured by the impedance tube method, and its noise reduction effect was analyzed. Planar sound waves are reflected by the sound-absorbing material at the end of the pipe and emitted as reflected waves in the pipe. The incident and reflected sound waves are shown in Fig. 1 below. Dual microphone experimental evaluation method.

The incident wave sound pressure PI and reflected wave sound pressure PR are24,25,26,27.

Where \(\:{\widehat{P}}_{I}\:\)and \(\:{\widehat{P}}_{R}\) are the complex amplitudes of PI and PR in the reference plane (x = 0), \({k_0}={k_0}^{\prime } - j{k_0}^{{\prime \prime }}\)is the complex wave number, \({k_0}^{\prime }\)is the real component, and \({k_0}^{{\prime \prime }}\)is the imaginary component of the attenuation constant.

Since the actual attenuation cannot be obtained from direct experimental measurements in such a short tube, the following mathematical model is developed for calculating the attenuation.

Where: w is the angular frequency, f is the frequency, co is the speed of sound equal to \(343.2\sqrt {\frac{T}{{293}}}\)m/s; where T is the temperature in Kelvin;\(\:\:{x}_{1}\) and\(\:{\:x}_{2}\) represent the distances of microphones p1 and p2, respectively, from the samples in the impedance tube as shown in Fig. 1, and the sound pressures p1 and p2 at the two microphone positions are.

The transfer function H12 of the total acoustic field between the two microphones can be obtained from Eqs. (4) and (5) as follows:

The complex amplitude reflection coefficient r from Eq. (3) is the ratio of the complex amplitude of the reflected wave to the complex amplitude of the incident wave at normal incidence. It can be simplified at x = 0 as:

Thus, Eq. (7) can be expressed as:

Transpose Eq. (8) to obtain r for x = 0:

besides

The equation can be factorized as:

Where s = X-x2 is the distance between the microphones. The complex amplitude reflection coefficient r at the reference plane (x = 0) can be determined from the measurement function, the distance xi from the first microphone, the distances between the microphones, and the complex wave number ko, which may contain the tube attenuation constant\({k_0}^{{\prime \prime }}\). Sometimes Eq. (8) is expressed as.

Where:

Where this is the sum of the transfer functions between the two microphones of the individual incident waves.

This is the transfer function of the reflected wave only between the two microphones. Returning to Eq. (13), the normal reflection coefficient r can be expressed as24,27

Where: rr is the real component, ri is the imaginary component, φr is the phase angle of the normal reflection coefficient. The sound absorption coefficient can be calculated from Eq. (13) or Eq. (16)24,27.

It is assumed to be equal to the complex power transfer factor\(\:\:{\left|r\right|}^{2}+\frac{Z}{\rho\:{c}_{0}}{\left|t\right|}^{2}=1\). The specific acoustic impedance ratio z can be calculated from Eq. (13) or Eq. (16) as follows.

where Z is the normal acoustic incidence impedance, defined as follows: p is the acoustic pressure at the reference plane (x = 0); u (343 m/s) is the velocity of the acoustic particle in the reference plane (x = 0), which is considered normal incidence for plane wave propagation.

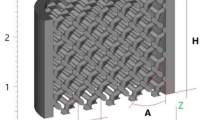

3D modeling

The structure of the acoustic metamaterial proposed in this paper is schematically shown in Fig. 2. It consists of two parts, the cylindrical cavity and the fan-shaped cavity. The sound-absorbing treatment is carried out through the irregular change of the depth of the cylindrical holes and the arrangement of the hole diameters. Pinholes with different diameters and varying degrees of depth are set up in this paper to expand the sound-absorbing band (shown in Fig. 2(a)). Where the depth of the cylindrical cavity varies in a stepwise manner (as shown in Fig. 3). The pore size distribution is categorized into three regions p, q, and r (as shown in Fig. 2(b)). The diameters of the holes in each region are 20 mm, 11 mm, 11–13 mm, respectively. The thin wall thickness of the metamaterial structure is t. The cutaway view of the proposed acoustic metamaterial structure is shown in Fig. 2(c), with d denoting the diameter of the panel holes. In previous studies, the size of cylindrical holes is generally uniform; to expand the acoustic absorption bandwidth, this paper sets up pinholes with different diameters. The geometric and physical characteristics that were used for simulation are shown in Table 1. The irregular cylindrical cavity structure of this study is essentially a “multi-order Helmholtz resonator array” - each cylindrical cavity can be considered as an independent Helmholtz resonance unit, and its resonance frequency is calculated as:

Where \(\:{c}_{0}\:(343m/s)\) is the speed of sound, \(\:S\) is the aperture cross-sectional area, \(\:{\nu\:}_{l}\) is the cavity volume + neck volume.

le effective neck length (m), due to the existence of “end effect” at both ends of the neck (air column vibration range beyond the physical neck), the actual neck length l (i.e., the depth of the cavity h) needs to be corrected. The correction formula is expressed as follows:

Where 0.8 is the end effect coefficient, which applies to cylindrical cavities “open at one end and closed at the other”, consistent with the paper’s construction of a “cavity with a rigid wall (closed) at the bottom and open at the top”. In the thesis, the cavity is divided into three zones, p, q and r, according to the aperture (Fig. 2 (b)), which correspond to different sub-bands of the low and medium frequency bands, and the following is the calculation of the intrinsic resonance frequency f0 of each sub-band one by one, in order to validate its match with the “high efficiency acoustic absorption frequency band of 510 ~ 970 Hz”.

-

1.

p-zone cavity (dp = 20 mm, hp = 50 mm):

$$\:{S}_{P}=\pi\:{\left(\frac{{d}_{P}}{2}\right)}^{2}\approx\:7.854\times\:{10}^{-5}{m}^{2}$$(24)$$\:{V}_{l,P}=1.5708\times\:{10}^{-5}{m}^{3}$$(25)$$\:{l}_{e,p}=58\times\:{10}^{-3}m$$(26)Substituting \(\:{S}_{p}{,V}_{l,p},{l}_{e,p}\) into Eq. (20) yields:

$$\:{f}_{0,p}=\frac{{C}_{0}}{2\pi\:}\sqrt{\frac{S}{{{v}_{l}}_{\bullet\:}{l}_{e}}}\approx\:506Hz$$(27)Similarly, it follows that in the q-region cavity (dp = 11 mm, hp = 35 mm) \(\:{f}_{0,q}\approx\:730Hz\), and in the r-region cavity (dp=12 mm, hp=25 mm) \(\:{f}_{0,r}\approx\:730Hz\). The resonance frequency interval of the three is about 220 Hz, forming a continuous sound absorption band, which is in perfect agreement with the result of “average sound absorption coefficient of 0.91 at 510~970Hz” in the simulation, which proves that the multi-cavity Helmholtz resonance theory is the core basis for the structural design of the present study rather than the random parameter combinations.

Simulation meshing

The pressure acoustics-frequency domain module of the finite element simulation software COMSOL Multiphysics was used for the simulation. The fluid domain is defined as the air that gives a port at the top to incident acoustic waves of 1 Pa. Through the upper air layer to reach the lower layer, the simulation model has the same parameters as the experimentally measured specimen, the boundary of the specimen is the hard sound field boundary, and the impedance of the thermo-viscous layer is set up in consideration of the viscous effect and the thermal effect on the acoustic absorption effect. The overall sound absorption coefficient of the system α = Eα/Ei=(Ei-Er)/Ei=1-r; Where: Ei-incident sound, Eα-acoustic energy absorbed by the material or structure, Er-acoustic energy reflected by the material or structure, r-reflection coefficient. The impedance Z is the complex ratio of the pressure of the medium over an area of the wavefront surface to the volumetric velocity through that area, where the volumetric velocity is the velocity of the medium flow through an area; Using the mesh function in the software, the model was divided into a free tetrahedral mesh with a more refined predefinition and a minimum cell size of 1 × 10−6. Simulation of the specimen model gives the results as well as the model mesh. Impedance tube and material meshing. In the unit size parameter of the user-defined window settings, the global maximum unit size is 1/8 of the minimum wavelength, λ = co/fmax/8.The maximum frequency fmax calculated in this paper is 1100 Hz, and the simulation analysis mesh division is shown in Fig. 4. In the meshing section, the total cell size is set to a maximum of 13.5 mm and a minimum of 1.69 mm. Since both the Perfect Matching Layer (PML) and the background pressure field are standard cylinders, in order to reduce the amount of computation, the mesh is plotted by scanning with a fixed number of cells set to three. The middle part is the thermo-viscous acoustic part, which is also scanned and mapped with a fixed cell number of 2. The last part is the effective acoustic structure part, which needs to be carefully divided in order to get accurate results, so a free tetrahedral mesh is used, and the maximum cell size is set to 5 mm.

Results and discussion

Simulation analysis

To verify the validity of the acoustic computational model and the transfer function post-processing computational procedure, numerical examples from Literature7 are used. As shown in Fig. 5, the calculated frequency range is 490 ~ 1110 Hz with a step size of 20 Hz, the density of air is 1.225 kg·m−3, and the speed of sound is 343 m/s. Finite element simulations were performed using the COMSOL Multiphysics acoustic-thermoviscosity module. The sound absorption of thermoviscous acoustics in COMSOL Multiphysics mainly stems from two major mechanisms: thermal conduction dissipation and viscous dissipation. When sound waves propagate, the fluid at the gas-solid interface compresses and heats up, expands and cools down. Due to the untimely heat exchange, the temperature gradient causes heat conduction, resulting in the conversion of sound energy into heat energy. At the same time, the viscosity of the fluid causes the velocity of the interface particles to lag behind the sound field, generating frictional energy consumption. The software precisely calculates the interface temperature and velocity gradients through models such as laminar flow boundary layers to quantify energy consumption. It is suitable for scenarios like porous materials and mufflers, and ultimately achieves the conversion of acoustic energy into thermal energy through the synergy of the two mechanisms, completing a wideband sound absorption simulation. In this work, explicitly use the “Pressure Acoustics - Frequency Domain” module (frequency range 400–1100 Hz, step size 20 Hz), superimpose the “Thermal Viscosity Acoustics” interface (taking into account the viscous and thermal effects), and supplement the interface coupling conditions (the thickness of the thermo-viscous layer is set to be 1/10th of the aperture, i.e. 1.1 mm); the incident port is set as “plane wave incidence”, sound pressure amplitude 1 Pa; the sample boundary is set as “rigid boundary” (no slip); the bottom is set as “total reflection boundary “The thickness of Perfect Matching Layer (PML) is set to 1/4 of the minimum wavelength (175 mm at 490 Hz) to absorb transmitted waves and avoid reflections; the refinement level of ”free tetrahedral grid” is clarified in the mesh delineation (Physical field control: acoustic domain grid). The refinement level of “free tetrahedral grid” is clearly defined in the grid division (physical field control: acoustic domain grid level 4, thermal adhesion domain level 5), the maximum cell size = λmin/8 (the wavelength of λmin is ≈ 312 mm at 1100 Hz, so the maximum cell size is 39 mm, and it is actually set to 13.5 mm to improve the accuracy), the minimum cell size = thermal adhesion layer thickness/5, (1.1 mm/5 ≈ 0.22 mm), and supplementary grid quality check results (average distortion ≤ 0.3, meeting the simulation accuracy requirements). The maximum cell sizes of 13.5 mm, 20 mm and 25 mm are used for simulation, and the sound absorption coefficients at 730 Hz are compared (0.98 for 13.5 mm, 0.95 for 20 mm and 0.89 for 25 mm), which indicates that the results converge at 13.5 mm and proves the reasonableness of the mesh setting; Supplemented with the modeling method of the present study, the “composite porous metamaterial” sound absorption curves are reproduced in7, and the average error of the simulation results is ≤ 5% with that of the literature data. “The average error between the simulation results and the literature data is ≤ 5%, which verifies the generality of the modeling method and ensures that the simulation process can be verified and reproduced. Two layers of air are added to the sample: the incident field, where the incident wave is located, and a perfectly matched layer simulating a reflection-free infinite field.

As shown in Fig. 6, the test data were analyzed, and the average sound absorption coefficient was 0.87, with a maximum of 0.98 at 730 Hz and a minimum of 0.40 at 490 Hz. From the absorption coefficient curve, it can be seen that in the frequency range of 510–970 Hz, the absorption coefficient is high, the average absorption coefficient reaches 0.91, and the acoustic metamaterials show good sound absorption performance in this frequency range.

The 490 Hz, 530 Hz, 570 Hz, 810 Hz, 930 Hz, and 1100 Hz velocity clouds are compared and analyzed as shown in Fig. 7. A sound velocity cloud map is an image that visualizes the distribution of sound propagation speed in a particular space or medium. At 490 Hz as well as at 530 Hz, the sound velocity amplitude occurs mainly at the larger cavity volume, and the maximum value of the velocity amplitude increases from 14 × 10−3 m/s to 20 × 10−3 m/s. As the frequency increases, the absorption performance increases between 490 Hz and 530 Hz. As the frequency increases, the velocity amplitude shifts to the smaller part of the cavity, and the maximum value of the velocity amplitude decreases, with a velocity amplitude of 6 × 10−3 m/s at 570 Hz. After the frequency of 810 Hz, the velocity amplitude is concentrated in a single small cavity, and the velocity amplitude increases significantly from 200 × 10−3 m/s to 300 × 10−3 m/s, and the acoustic performance showed a weakening trend. A sound pressure cloud map is a visual representation of the sound pressure distribution. Sound pressure is an important physical quantity that describes the change of medium pressure during sound wave propagation, and it reflects the intensity and energy distribution of sound waves. After obtaining sound pressure data through measurements or calculations, data processing software can be used to convert this data into the form of a cloud diagram, thus visualizing the distribution of sound pressure. Sound Pressure Level (SPL) is a key physical quantity describing the intensity of acoustic energy, and its value directly reflects the degree of energy concentration in the local acoustic field (the higher the SPL is, the denser the local acoustic energy is). The difference between the cloud diagrams of different frequencies in Fig. 8 is a visualization of the “coupling of acoustic wave frequency with the resonance characteristics of the cavity structure”. Figure 8 (a) shows that the SPL of the background pressure field (the region of the incident sound field outside the cavity) at 490 Hz is concentrated in the range of 80–85 dB, while the sound pressure inside the cavity is uniformly distributed and has low values (there is no region of significantly high SPL). At this time, the air column in the cavity does not enter the “mass - spring” resonance state, and cannot effectively capture the incident acoustic energy, resulting in a weak distribution of acoustic energy in the background field, with no localized energy concentration. Figures 8 (b)-(e) (530 Hz, 570 Hz, 810 Hz, 930 Hz) show that the SPLs of the background pressure field in this band are generally ≥ 90 dB, and there are obvious “high SPL clustered areas” (red/darker areas in the cloud) inside the cavity, and the clustering location gradually shifts from “large volume cavity” to “small volume cavity” with the increase of the frequency. The location of aggregation gradually shifts from “large-volume cavity” to “small-volume cavity” with the increase of frequency: This frequency band covers the intrinsic resonance frequency of the p, q, r three-zone cavity, the air column in the cavity into the resonance state -- the incident sound wave and the air column vibration to produce a “standing wave superposition”, in the standing wave wave belly position to form a sound pressure peak (i.e., high SPL region in the cloud diagram). When the frequency rises, the wavelength of the sound wave shortens. Figure 8 (f) shows that the background pressure field SPL remains ≥ 90 dB at 1100 Hz, but the extent of the high SPL region inside the cavity is significantly reduced and concentrated in the r-region (smallest volume) of the cavity, with some areas of “acoustic pressure faults” (well defined boundaries between dark and light colors in the cloud diagram). 1100 Hz is slightly higher than the intrinsic resonance frequency of the cavity in the r-zone (≈ 960 Hz), the cavity enters the “over-resonance state” - the air column vibration frequency exceeds its own intrinsic frequency, the vibration amplitude is weakened, and the superposition effect of the standing wave is weakened, resulting in a high SPL zone. Reduced range. The transfer of the sound pressure concentration area from p-zone → q-zone → r-zone at 530 ~ 930 Hz in Fig. 8 proves that the p-zone, q-zone and r-zone cavities correspond to different sub-frequencies of the low and mid-frequency bands (530 ~ 650 Hz, 650 ~ 850 Hz, and 850 ~ 930 Hz), and that complete sound field coverage of the target frequency band of 510 ~ 970 Hz is realized through “multi-order resonance” -- if the conventional “uniform aperture - depth” cavity is used, only a single frequency can be formed (narrow-band absorption). 970 Hz target frequency band complete sound field coverage -- if the traditional “uniform aperture - depth” cavity, only at a single frequency to form a sound pressure concentration (narrow band sound absorption), while the structure of the “irregular design The structure’s “irregular design” directly supports the performance goal of “broadband absorption” by providing zoned coverage of the sound field.

Experimental results

To verify the validity of the acoustic calculation model and the transfer function post-processing calculation program, the machined part structure was prepared using the 3D printing process. A sample with a diameter of 99.9 mm and a thickness of about 50 mm (shown in Fig. 9) was used for this validation. Using Stereolithography Apparatus (SLA) Light curing printing technology (resolution size is 60-60-60 cm, infill density is 30%) and photosensitive resin as raw material. As shown in Fig. 10, the diameter of the impedance tube Di is 100 mm, the distance between the microphone and the specimen ds is 100 mm, the measurement mode of the exchange channel method is used, the microphone distance dr is 70 mm, and the sound absorption coefficient of the acoustic metamaterial structure is measured by the impedance tube acoustic test system. The measurement frequency range was 400–1100 Hz, and the acoustic absorption was determined using the transfer function method according to EN ISO 105,342 in the frequency range of 400–1100 Hz. Signal acquisition for both microphones was used. Experimental data processing was performed using commercial software.

An impedance tube test was performed as shown in Fig. 11, showing the results of the test data for the sound absorption coefficient in the frequency range of 400–1100 Hz. The average absorption coefficient of 0.70, the maximum value of the absorption coefficient of 0.99 (corresponding to 803 Hz), and the minimum value of the absorption coefficient of 0.06 (corresponding to 803 Hz) were observed over the entire study range. In the frequency range of 500–1000 Hz, the sound absorption coefficient of the test value is good, and the sound absorption effect is significant. It can be seen that the acoustic metamaterials designed in this paper have a good sound absorption effect.

As shown in Fig. 12, the test and simulation results are in good agreement, and the test verifies the validity of the simulation. The differences between 500 and 1000 Hz are insignificant, and the error between test and simulation is within acceptable limits. The test and simulation results are in good agreement over the entire frequency range. The error between the test and simulation exists:

(1) In this paper, when the test specimen is prepared, there will be gaps between the specimen and the wall of the standing wave tube, and these factors affect the measurement of the sound absorption coefficient.

(2) Since the air domain model without wall thickness established in the finite element calculation process ignores the influence of the acoustic wave in the cavity due to wall reflection on the overall structural coupling effect in the lower frequency bands in the actual situation, there will be some deviation in the measured results.

(3) The experimental bandwidth is slightly larger than the theoretical and simulation results. This is mainly due to finite tolerances in the dimensions of the fabricated samples. The peak amplitudes of the experimental curves are smaller than those of the finite element and theoretical curves, which may be attributed to suboptimal test conditions. Air leakage may have occurred at the boundary.

Overall, based on simulations and experiments, it has been determined that the structure has effective sound absorption properties at low and medium frequencies (f ≤ 1100 Hz). It is expected that the subsequent optimization of the phonon crystal structure and array arrangement can further enhance its vibration noise control performance. However, the vehicle’s variable internal geometry and irregular body structure complicate the design and arrangement of phononic crystals. Therefore, developing phononic crystals for precise control of vehicle interior/exterior vibration noise will be the focus of future research here. Meanwhile, the component materials of the phononic crystal in the paper are prepared by 3D printing, which will be an unreliable preparation method if formally put into engineering application, and a stronger, stable, and long-lasting preparation method needs to be sought for replacement in the future.

Conclusion

In this paper, from the perspective of the acoustic performance of acoustic metamaterial structures, the impedance tube method and the acoustic finite element simulation and analysis method are used to predict the sound absorption coefficients of the designed acoustic metamaterials by using the common transfer matrix method. The acoustic absorption properties of acoustic metamaterials consisting of different cavities are mainly investigated. It was found that the size of the apertures and the depth of the cavities, as well as the periodic arrangement, determine the acoustic absorption performance of this acoustic metamaterial designed by us.

From the simulation point of view, this material can reduce the broadband noise in the range of 490–1100 Hz with an average sound absorption coefficient of 0.87, with a maximum of 0.98 (at 730 Hz) and a minimum of 0.40 (at 490 Hz). At the frequency range of 510–970 Hz, the average absorption coefficient reaches 0.91, and the acoustic ultramaterials show good sound absorption performance.

From an experimental point of view, impedance tube experiments show that the sound absorption coefficient prediction method works well and can be used for low and medium-frequency noise attenuation. The average absorption coefficient of 0.70, the maximum value of the absorption coefficient at 803 Hz, and the minimum value of the absorption coefficient of 0.06 at 400 Hz were observed over the whole range of the study. In the frequency range of 400–1100 Hz, the measured value of the acoustic absorption coefficient of the test data is in good agreement with the simulation value, which verifies the accuracy of the simulation.

This study provides an effective way to design broadband sound absorbers in a limited space. The developed acoustic metamaterials have the advantages of thin layer thickness, low frequency, and wide bandwidth, which have important applications in noise reduction. In addition, acoustic metamaterials are also expected to be used in automotive engines and automotive interiors to achieve effective control of low and medium-frequency noise in automobiles. Acoustic metamaterials mainly achieve noise control through superior structural performance, have a long service life, a production process that is almost pollution-free, are easy to assemble, and possess other advantages. Moreover, in terms of noise reduction effect, it is stronger than traditional materials. Even for certain specific frequencies, traditional materials cannot achieve high sound absorption efficiency. In the field of automotive noise reduction, there is a very broad space for development.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Hu, Q. et al. Investigation on the technology of automobile vibration and noise reduction based on body-in-white structure. Key Eng. Mater. 474, 676–680 (2011).

Horváth, K. & Zelei, A. Simulating Noise, Vibration, and harshness advances in electric vehicle powertrains: strategies and challenges. World Electr. Veh. J. 15, 36 (2024).

Sakamoto, S., Sato, K. & Muroi, G. Improvement of Sound-Absorbing wool material by laminating permeable nonwoven fabric sheet and nonpermeable membrane. Technologies 12 (10), 195–195 (2024).

Husain, H. N. S. et al. Development of Kenaf Nonwoven as automotive noise absorption.Appl. Mech. Mater. 4752, 101–105 (2019).

Zhang, W. & Xin, F. Coiled-up structure with porous material lining for enhanced sound absorption. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 256, 10848 (2023).

Gai, X. L., Guan, X. W. & Cai, Z. N. Acoustic properties of honeycomb-like sandwich acoustic metamaterials. Appl. Acoust. 199, 10901 (2022).

Gao, N., Tang, L. & Deng, J. Design, fabrication and sound absorption test of composite porous metamaterial with embedding I-plates into porous polyurethane sponge. Appl. Acoust. 175, 107845 (2021).

Lu, Q., Li, X. & Zhang, X. Perspective: acoustic metamaterials in future engineering. Ei 17, 22–30 (2022).

Wang, D. W., Wen, Z. H. & Glorieux, C. Sound absorption of face-centered cubic sandwich structure with micro-perforations. Mater. Des. 186, 108344 (2020).

Xie, S., Yang, S. & Yang Sound absorption performance of a filled honeycomb composite structure. Appl. Acoust. 162, 107202 (2020).

Liu, Y., Chen, M. & Xu, W. Fractal acoustic metamaterials with subwavelength and broadband sound insulation. Shock Vib. 2019 (1), 1894073 (2019).

Sun, W., Wang, Y. & Yuan, H. Low-frequency ultra-broadband absorbers with conical cavity-coupled porous materials. Appl. Acoust. 221, 110035 (2024).

Ruan, H. & Li, D. Bandgap characteristics of bionic acoustic metamaterials based on spider web. Eng. Struct. 308, 118003 (2024).

Liu, C. R., Wu, J. H. & Yang, Z. Ultra-broadband acoustic absorption of a thin microperforated panel metamaterial with multi-order resonance. Compos. Struct. 246, 112366 (2020).

Zieliński, T. G., Dauchez, N. & Boutin, T. Taking advantage of a 3D printing imperfection in the development of sound-absorbing materials. Appl. Acoust. 197, 108941 (2022).

Vasina, M., Monkova, K. & Monka, P. P. Study of the sound absorption properties of 3D-printed open-porous ABS material structures. Polymers-Basel 12 (5), 1062 (2020).

Rafique, F., Wu, J. H. & Liu, C. R. Low-frequency sound absorption of an inhomogeneous micro-perforated panel with j-shaped cavities of different depths. Acoust. Aust. 50 (2), 203–214 (2022).

Park, S. H. Acoustic properties of micro-perforated panel absorbers backed by Helmholtz resonators for the improvement of low-frequency sound absorption. J. Sound Vib. 332, 4895–4911 (2013).

Melnikov, A., Maeder, M. & Friedrich, N. Acoustic metamaterial capsule for reduction of stage machinery noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 147 (3), 1491–1503 (2020).

Arjunan, A., Baroutaji, A. & Robinson, J. Acoustic metamaterials for sound absorption and insulation in buildings. Build. Environ. 2024, 111250 (2024).

Gardiner, A., Domingo-Roca, R. & Windmill, J. F. C. An adjustable acoustic metamaterial cell using a magnetic membrane for tunable resonance. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 15044 (2024).

Ruan, H., Yu, P. & Hou, J. Low-frequency band gap design of acoustic metamaterial based on cochlear structure. Smart Mater. Struct. 33 (2), 025017 (2024).

Chen, A., Yang, Z. & Zhao, X. Composite acoustic metamaterial for broadband low-frequency acoustic Attenuation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 20 (1), 014011 (2023).

Vasile, O. & Bugaru, M. Experimental vs. numerical computation of acoustic analyses on the thickness influence of the multilayer panel. TCYB 11 (1), 1 (2022).

EN 10534-2. Acoustics-Determination of Sound Absorption Coefficient and Impedance in Impedance Tubes Part 2: Transfer-Function Method (ISO, 2002).

Vasile, O., Miculescu, F. & Voicu, S. I. Correlation aspects between morphology, infrared and acoustic absorption properties of various materials. Optoelectron. Adv. Mat. 6, 631–638 (2012).

Gai, X. L., Guan, X. W. & Cai, Z. N. Acoustic properties of honeycomb-like sandwich acoustic metamaterials. Appl. Acoust. 199, 109016 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by Noise Reduction Performance of Composite Acoustic Materials (2024JBE01L02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhenhua Hou: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration, Resources, Experiment. Ke Zhang: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Analysis of results. Zhenfu Zhou: 3D Model building. Yuxiang Zheng: Conceptualization. Jianqiang Wang: Reviewed the manuscript. Libo Wang: Experiment, Conceptualization, Analysis of results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, Z., Zhang, K., Zhou, Z. et al. Low and medium frequency acoustic absorption properties of acoustic metamaterials with irregular cylindrical cavities. Sci Rep 15, 40586 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24387-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24387-9