Abstract

Conventional solar chimney power plants (SCPPs) are hindered by low energy conversion efficiency and lack of integrated approaches for maximizing simultaneous green hydrogen and electricity production, especially when multiple interdependent system parameters interact nonlinearly. The study aims to optimize a novel hybrid SCPP configuration for dual-output, sustainable electricity and green hydrogen, by systematically analysing the influence and interplay of chimney inclination, solar radiation, collector absorptivity, and turbine pressure drop. Using CFD simulations that solve mass, momentum, and energy conservation equations, the research models complex buoyancy-driven flows within conical chimneys while integrating an electrolysis unit for hydrogen generation. Statistical correlation, priority weighting (AHP), and k-means clustering are employed to identify critical parameter dependencies, prioritize operational outcomes, and group optimal performance regimes. The optimal configuration is determined at an 8° chimney inclination, 800 W/m2 solar radiation, collector absorptivity of 0.88, and 95 Pa turbine pressure drop, yielding an airflow velocity of 9.8 m/s, power output of 16.1 kW, and hydrogen generation of 0.62 kg/day. Correlation analysis reveals electricity and hydrogen outputs are maximized primarily by airflow velocity and power output under these synergistic parameter sets. The study establishes an effective operational envelope for SCPPs that achieves both high electricity and green hydrogen yields, outperforming conventional single-output designs. The integrated multi-objective approach and nuanced parameter selection lay a foundation for deploying versatile, cost-effective renewable energy systems tailored for dual-generation, thus advancing SCPP viability for sustainable energy transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solar Chimney Power Plants (SCPPs) are promising and sustainable solutions for renewable energy generation, since they convert solar radiation into electricity through an innovative thermal process1. As global energy demand increases due to population growth and globalization, the depletion of natural resources poses significant threats, prompting a focus on alternative clean energy sources2. SCPPs offer an eco-friendly, emission-free option, making them effective tools for addressing accelerated climate changes. Solar chimneys operate differently from traditional photovoltaic systems3. They heat air under a wide glass-covered collector, causing the hot air to rise through a tall chimney. This air movement drives turbines to generate electricity4. A key advantage of this technology is its ability to function after sunset, enabled by the collector’s heat storage capacity. These plants require large areas and high levels of solar radiation, making them especially suitable for arid regions with favourable climatic conditions5.

The temperature inside the solar chimney tower can be effectively utilized for simultaneous power and hydrogen generation by leveraging the high-temperature airflow for electricity production while using excess thermal energy for hydrogen-related processes6. As solar radiation heats the air beneath the transparent collector, the rising hot air drives turbines to generate electricity7. The thermal energy retained within the chimney walls and the collector system can be further harnessed for hydrogen production through thermochemical methods. The high-temperature environment within the chimney can support hydrogen production via thermochemical water splitting or steam reforming of bio-derived gases, where heat energy aids in breaking molecular bonds to release hydrogen8. By integrating hydrogen production with electricity generation, SCPPs can provide a dual-output system, enhancing their efficiency and economic feasibility9. This combined approach not only improves energy utilization but also contributes to the broader goal of sustainable and renewable energy development.

The system interactions between SCPP are highly complex due to the nonlinear dependencies between thermodynamic, aerodynamic, and heat transfer phenomena10. Variations in solar intensity, ambient temperature, and chimney geometry create dynamic changes in airflow patterns, leading to fluctuating turbine efficiency and inconsistent hydrogen production rates11. Additionally, factors like heat retention, pressure differentials, and material properties further complicate the prediction of system performance12. The simultaneous occurrence of convective, conductive, and radiative heat transfer within the chimney structure adds another layer of complexity, making it difficult to establish direct analytical relationships between inputs and outputs13. These interdependencies require advanced computational models to accurately predict performance and optimize operational parameters. Modern computational tools such as machine learning (ML) and priority-based AI models offer robust solutions to analyse and optimize these complex interactions14. Traditional models often fail to capture real-time variations and multi-variable correlations, whereas ML algorithms can efficiently learn from large datasets to provide accurate predictions15. Additionally, priority models can dynamically rank and adjust input parameters.

Smaisim et al.16 examines a solar tower system to maximize electrical energy production, evaluating its components across five Iranian cities with different climates. Results show Shiraz city achieving the highest output at 20 kW/m2, while Mashhad records the lowest at 15 kW/m2. Abdelsalam et al.17 explored hybrid solar chimney power plant with a seawater pool and sprinklers, enabling dual operation as an SCPP by day and a downdraft cooling tower by night. Analysing 16 Saudi cities, results show a 55% increase in power, 20% higher freshwater yield, and a 56% CO2 reduction, with optimal performance in central and southern regions. Fallah and Valipou18, studied a sloped solar chimney power plant using 3D simulations, validated with experimental data, to address height limitations in conventional designs. Results show a peak air velocity of 2.73 m/s at 800 W/m2 solar radiation, with a 25% chimney height reduction lowering velocity to 2.07 m/s and slightly increasing air temperature. Mehranfar et al.19 investigated the theoretical, experimental, and numerical research on optimizing solar chimney power plants by improving chimney, collector, and power conversion unit design. It explains hybrid systems and innovative add-ons that enhance efficiency and enable by-product generation like distilled water. Saleh et al.20 reviewed various methods to enhance solar chimney power plant efficiency, focusing on integrating thermal storage materials, and engineering modifications to chimney design.

Prior studies of solar chimney systems, were limited by simplistic parameter studies that failed to capture the complex interdependencies affecting power and hydrogen generation simultaneously. This study addresses these limitations by employing Pearson correlation to quantify variable relationships, weighted prioritization of influential parameters, and clustering to identify optimal operational regimes within multidimensional datasets. This hybrid approach enhances predictive accuracy and system optimization by integrating nonlinear interactions, thereby overcoming prior models’ inability to optimize multiple, conflicting objectives in hybrid energy systems. While previous studies have reviewed upon divergent multiple chimney designs, systematic studies specifically focusing on conical geometries remain limited. Moreover, detailed evaluations of chimney inclination angles and their combined effects on thermal and dynamic performance are sparse in the literature due to complex interactions between its parameters, representing a critical research gap.

The contemporary study employs simultaneous optimization of electricity and green hydrogen production within a single SCPP system, achieved by integrating complex interacting parameters not addressed in earlier works. By coupling real-time electrolysis with advanced aerodynamic tuning, the research demonstrates a unique multi-functional renewable energy generation strategy. Recent studies have shown a growing interest in hybrid SCPP architectures, such as SCPP-desalination and SCPP-cooling tower systems, as well as techno-economic assessments of SCPP-electrolysis coupling21. The main challenges reported include intermittency of electricity production, appropriate sizing of the electrolyzer, hydrogen storage, water requirements (for electrolysis or desalination), and overall economic viability22. The novelty of this study lies in the unique and complex integration of multiple highly influential parameters primarily chimney inclination angle, solar radiation levels and turbine pressure drop, analysed simultaneously to optimize both electricity generation and green hydrogen production in a single system. This systemic combination, including the coupling of buoyancy-driven airflow dynamics with electrolysis-based hydrogen synthesis, marks a novel approach in maximizing thermal-to-electrical and thermal-to-chemical energy conversion efficiencies together. Furthermore, the study pioneers quantifying the interactive effects of these parameters through Pearson correlation, AHP prioritization, and k-means clustering to comprehensively define an optimal operational envelope for dual-outputs. The following objectives needs to be addressed in the study:

-

Pearson-r correlation analysis will be performed to quantify the relationship between input parameters and output variables, identifying the strength and direction of their dependencies.

-

Priority for outcomes will be determined using the AHP to systematically rank and weigh their significance based on multiple criteria.

-

The k-means machine learning method will be applied to cluster the data, grouping similar patterns to identify optimal operational conditions for the system.

-

The best-clustered operating conditions will be analysed and compared to identify the most efficient and balanced system performance.

System design and equipment simulation

System design and chimney geometry variations

The SCPP consists of several key components, including a collector, a ground absorber, a wind turbine near the chimney base to convert airflow energy into kinetic energy for power generation via a generator, and a chimney. The chimney serves as the central unit, enabling updraft caused by the heated air between the collector and the ground. This process drives natural convection, allowing air to circulate from the collector inlet to the chimney outlet. In this study, a simplified SCPP model is proposed, consisting of only two elements: a heat source to generate natural convection and a conical chimney with varying angles.

Table 1 presents the geometric parameters of the system. In this study, the only variable parameter is the chimney’s inclination angle. Various chimney shapes with different angles were analysed to determine the optimal configuration for enhancing the power output and hydrogen generation for the SCPP.

In a prior study which investigated through experiments, variations in the mean Nusselt number along the walls for different cone opening angles (0°, 2°, 5°, 6°, 8°, 11°, and 13°), and identified θ = 8° as the critical cone angle at which convective heat transfer between the walls and the air began to improve23. Chimney angles of 9° and 10° were not considered, as preliminary analysis indicated diminishing returns in airflow velocity and power output beyond 8° due to increased flow separation and potential structural complexity. Higher angles may also induce aerodynamic instabilities and reduce buoyancy-driven flow efficiency, making such configurations less practical. Consequently, the selected parameter range of 0° to 8° sufficiently captures the critical transition region of SCPP performance, balancing flow acceleration and structural feasibility within realistic design constraints.

Equipment selection and arrangement

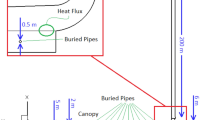

The solar conical chimney system establishes several interlinked components to effectively produce hydrogen by using solar energy as shown in Fig. 1. Solar collectors focus sun rays into thermal energy whereas air inside the air chimney achieves buoyancy and causes an updraft24. The air flowmeter determines ventilation speed to ensure proper turbine operation before the airflow reaches the wind turbine to produce electrical power. The water splitting system receives power from the generated electricity to operate its flow meters and tank for controlled water supply to the electrolysis unit. The unit converts electrical power into water splitting through which water becomes separated into hydrogen and oxygen gases while efficiency optimization relies on system parameters like turbine pressure drop and airflow velocity25,26.

An AI control system together with sensor units continuously checks performance through automated adjustments to detect airflow and pressure changes within the energy output deviations27,28. After production the hydrogen is transfer to the production unit to undergo purification treatment until storage is complete. Regulated hydrogen supply for secondary purposes is achieved through high-pressure tanks and adsorptive materials in the storage system which ensures secure hydrogen containment. Each system component works together in uninterrupted energy conversion through a process which optimizes power production and generates hydrogen for sustainable energy needs.

Assumptions and boundary conditions for the simulation model

The study investigates the thermal-hydrodynamic behaviour under defined boundary conditions to optimize system performance. Understanding the assumptions is crucial for accurately modelling heat transfer and flow characteristics as shown in Table 2. The following assumptions are taken into consideration for the simulation analysis:

-

Steady-state flow: The fluid flow and temperature distributions are assumed to be time-independent, ensuring a stable analysis without transient effects.

-

Incompressible flow: The density variations are negligible, allowing the simplification of Navier-Stokes equations for easier computational modelling.

-

Axisymmetric flow: The model assumes no variation in the circumferential direction, reducing computational complexity while maintaining accuracy.

-

No-slip condition at the wall: The radial and axial velocities are set to zero at the cylinder wall, implying viscous interactions that influence velocity gradients near the boundary.

-

Negligible axial gradients at the outlet: The assumption ensures a fully developed flow at the outlet, preventing artificial acceleration or deceleration effects.

-

Constant fluid properties: The fluid viscosity, thermal conductivity, and specific heat are considered constant, simplifying the energy and momentum equations.

-

Turbulent flow assumption: The assumed to be turbulent in nature due to high Reynolds numbers, driven by increased airflow velocity and thermal buoyancy, requiring turbulence modelling for accurate analysis.

The CFD simulations for the hybrid solar chimney power plant were conducted using ANSYS Fluent with an emphasis on modelling the buoyancy-driven turbulent airflow within the conical chimney structure. The specific turbulence model selected for this study was the standard k − ε model, which is highly relevant due to its robustness in capturing the essential features of recirculation, turbulence generation, and dissipation within high-Reynolds-number with axisymmetric flows commonly observed in natural convection-dominated systems like solar chimneys. Compared to models such as k − ω and Reynolds Stress Model (RSM), k − ε model balances computational efficiency and accuracy—where the k − ω model excels in near-wall precision but becomes sensitive to free-stream conditions, and RSM is superior for complex anisotropic turbulence but at significant computational cost. The k − ε model is preferred in this context for its track record in predicting both core and boundary layer turbulence in solar-related buoyant plumes and for reliably estimating velocity and temperature profiles with reasonable resource requirements, especially when grid independence has been validated.

Capturing the flow dynamics inside the conical chimney presented several challenges, largely due to the complex interaction of buoyancy, thermal gradients, and geometric divergence. The conical shape, with varying inclination angles, induces non-linear acceleration of heated air, causing strong gradients, vortex formation, and flow separation regions that are sensitive to mesh resolution and model selection. One notable challenge was to resolve these gradients without introducing excessive numerical diffusion, which can dampen the characteristic plume and distort velocity/temperature profiles. Ensuring grid independence was critical for stability and accuracy. In complex conical geometries, even the best turbulence models may struggle with transitional flows and recirculation at the inlet or near the wall boundaries, an issue addressed through careful boundary condition setting and validation against experimental benchmarks. Ultimately, the selected k − ε model facilitated reliable prediction, but ongoing challenges remain in accurately modelling secondary flow structures and their impact on energy extraction efficiency.

Methodology

The methodology begins with system design incorporating a simplified hybrid solar chimney power plant with variable chimney inclinations, a heat source, turbine, and integrated electrolysis unit to produce electricity and green hydrogen. In the next step development of a CFD model using steady-state, incompressible, turbulent flow assumptions to simulate thermodynamic buoyancy-driven airflow and heat transfer is performed. Further, grid generation and independence tests are conducted to ensure numerical accuracy and mesh sensitivity. Moreover, parametric simulations are performed by varying chimney angle, solar radiation, collector absorptivity, and turbine pressure. Finally, AHP is applied for prioritizing performance outcomes followed by k-means clustering for identifying optimal operating regimes, enabling robust multi-criteria design optimization within computational feasibility.

Outcomes and their relevance for the system

The system serves critically to analyse buoyancy-driven flow dynamics within conical chimney designs which optimizes natural convection for passive cooling usage. The analysis of velocity distribution leads to better thermal plume performance eventually decreasing energy wastage while preventing the flow separation. Chimney angle choice relies on the test outcomes to achieve peak heat dissipation and steady airflow performance.

-

(a)

Turbine pressure drop (\(\:\varvec{\Delta\:}{\varvec{P}}_{\varvec{t}}\), Pa).

The pressure drops across the turbine is given by

where

\(\:{P}_{in}\) and \(\:{P}_{out}\) are the inlet and outlet pressure, \(\:\rho\:\) is the air density, \(\:V\) is the velocity, and \(\:{C}_{d}\) is the discharge coefficient. This parameter is critical as it directly affects the efficiency of power extraction, ensuring optimal turbine operation while maintaining sufficient airflow for sustained chimney draft.

-

(b)

Airflow velocity (\(\:\varvec{V}\), m/s).

The velocity of air inside the chimney is determined using Bernoulli’s equation

where, \(\:g\) is gravitational acceleration and \(\:H\) is the chimney height. Airflow velocity influences the convective heat transfer, which dictates the updraft strength, ensuring maximum kinetic energy conversion for efficient power generation.

-

(c)

Power output (\(\:\varvec{P}\), kW).

The power output from the turbine is expressed as

where, \(\:{\eta\:}_{t}\) is turbine efficiency, \(\:\dot{m}\) is mass flow rate, h is height, and \(\:A\) is the turbine cross-sectional area. This equation highlights how thermal gradients and airflow dictate energy conversion, ensuring that the chimney effectively harnesses solar energy for power generation.

-

(d)

Hydrogen generation (\(\:\dot{{\varvec{m}}_{\varvec{H}},\:\varvec{k}\varvec{g}/\varvec{d}\varvec{a}\varvec{y})}\).

Hydrogen production is calculated using electrolysis efficiency

where, \(\:{\eta\:}_{elec}\) is the electrolysis efficiency, and \(\:{\Delta\:}{H}_{H}\) is the enthalpy change of hydrogen production. This parameter is crucial in assessing the feasibility of integrating renewable hydrogen production within the solar chimney system contributing to sustainable energy solutions.

The results in Table 3 are generated by systematically varying the core operating parameters of the proposed system and then calculating corresponding airflow velocity, power output, and hydrogen generation using thermodynamic and fluid mechanics equations specific to the system’s architecture. Each data point in the table is derived by incorporating relevant governing equations for mass, momentum, and energy conservation, as well as the performance parameters for airflow velocity (via Bernoulli’s analysis), power output (turbine work), and hydrogen yield (electrolysis efficiency involving enthalpy change).

AHP method application

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) applies weightages to various outcomes through relative significance assessment in system performance evaluation. AHP measures the effect of each parameter on system efficiency by using hierarchical criteria and pairwise comparison29. The weights generated by the process represent the individual impact levels so the approach delivers unbiased criteria for additional clustering analysis. The calculation of weights through this methodology provides more accurate cluster formation because significant parameters gain increased influence in grouping processes. The integrated method enhances the classification precision of system performance circumstances to produce optimal operational protocols30.

In this study, ANSYS Fluent simulation data is initially generated sequentially for varied parameter sets, producing detailed flow, thermal, and performance outputs. These outputs form the input dataset for a hybrid post-processing stage where AHP calculates weighted priorities of outcomes based on their impact on the system, which then guides the k-means clustering to segment and optimize performance scenarios. The workflow strategically uses CFD to capture physics accurately, AHP for decision weighting to account for multi-objective criteria, and k-means for robust unsupervised optimization of clustered scenarios, ensuring computationally efficient system design analysis.

Prioritization within the k-means algorithm in this study was achieved by initially applying the AHP derived weightages to outcome variables, based on their contribution to system efficiency and real-world viability. These weightages were embedded into the k-means final clustering, which segmented multi-dimensional datasets according to their weighted Euclidean proximities to optimal performance benchmarks, forming clusters that reflect trade-offs between outputs. The principal criterion for defining “priority” was therefore a composite score integrating system dynamics, thermoelectric conversion efficiency, and electrolysis performance, with the most dominant features steering centroid calculation and cluster ranking. This allowed the clustering not just to reflect raw performance but also scientific relevance and practical optimization, ensuring that the most “priority” configurations maximized both green hydrogen yield and electricity generation within the modelled operational constraints.

k-means machine learning algorithm implementation

The k-means modelling technique enables clustering of optimal data points through similarity-based segmentation which leads to effective groupings of operational optimal conditions. The k-means algorithm begins its operation by identifying clusters of data points that promote optimal system performance by minimizing intra-cluster variance31. k-means modelling helps choose the most efficient configurations by locating groups of data that exclude substandard or outlier conditions. The optimized clusters form the basis for refining the model because it leads to improved decision-making through high-performing scenario selection and result in better system analysis accuracy for future developments32. The following are the steps of the above technique:

Step 1: Initialize centroids.

The k cluster centres are initialized which correspond to actual data points within the dataset or be generated within the data’s range, guided by algorithm-determined weights.

Step 2: Assign data points to clusters.

-

Compute the distance of each data point from all cluster centers.

-

Assign each data point to the cluster represented by the nearest center.

-

The Euclidean distance metric is typically utilized for distance calculation.

Step 3: Update centroids.

-

Recalculate the cluster center for each cluster by taking the mean of all data points assigned to it.

-

The formula for calculating the new centroid is as follows:

where:

-

\(\:{\mu\:}_{q}\) is the new centroid of cluster \(\:q\).

\(\:{P}_{q}\) is the number of data points in cluster \(\:q\).

-

\(\:{y}_{r}\) represents the coordinates of data point \(\:{r}^{th}\) in cluster \(\:q\).

Step 4: Repeat steps 2 and 3.

-

Repeat steps 2 and 3 until the stopping criteria are met. These criteria could include reaching a predefined maximum number of iterations, minimal movement in cluster centers, or no change in point-to-cluster assignments.

-

The goal of the k-means algorithm is to minimize the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS), which is the sum of the squared distances between each data point and its associated cluster center. This can be mathematically expressed as:

Mathematically, it can be represented as:

where \(\:Q\) is the number of clusters, \(\:{P}_{q}\) is the number of data points in cluster \(\:q\), \(\:{y}_{r}\) represents the coordinates of data point \(\:{r}^{th}\) in cluster \(\:q\), \(\:{\mu\:}_{q}\) is the centroid of cluster \(\:q\), || || denotes the Euclidean distance.

Process simulation

The conservation and governing equations for a 2-D turbulent incompressible steady flow are suggested below for simplification of the complex simulation analysis:

The equation for mass conservation:

The equation for r-momentum conservation:

The equation for z-momentum conservation:

The equation for energy conservation:

In this context, the viscous dissipation function for an incompressible fluid in the (r-z) dimensions is defined as \(\:{\varphi\:}_{v}\):

The \(\:k\)-equation:

The \(\:\epsilon\:\)-equation:

Moreover, a grid sensitivity analysis is undertaken to enumerate the meshing process. The mesh is not significantly affecting the velocity results, ensuring numerical stability as shown in Fig. 2. The strategized velocity profiles for diverse mesh sizes (49,383, 83,931, and 129,640 nodes) displays minimal variation, justifying that further mesh refinement does not significantly impact the result. The grid size of 83,931 demonstrates a correct relation between processing speed and solution accuracy. An appropriate mesh selection allows the system to reduce computational costs without compromising its ability to capture essential flow and heat transfer characteristics within the solar chimney system.

The Fig. 3a shows the temperature distribution (T) at the cylinder inlet, comparing experimental (Te) and numerical ((Tn) results. Both profiles exhibit a symmetric pattern, with two prominent peaks corresponding to regions of high thermal activity. The experimental data shows sharper fluctuations, while the numerical model smooths out variations, likely due to numerical diffusion in simulations. The agreement between the two curves validates the computational model’s accuracy in capturing thermal behaviour, confirming that the selected mesh resolution effectively represents the temperature field without significant numerical artifacts.

The Fig. 3b illustrates the velocity distribution (V) at the cylinder inlet, comparing experimental (Ue) and numerical results (Un). Both profiles exhibit a symmetric M-shaped pattern, indicating the presence of two high-velocity regions near the outer edges and a central low-velocity zone. The experimental velocity shows slightly lower values in the peak regions than the numerical, possibly due to measurement uncertainties or turbulence effects not fully captured in the simulations. The close agreement between the two curves suggests that the computational model effectively predicts the airflow behaviour, validating the selected grid resolution for accurate flow field representation as depicted in Fig. 3c.

Results and discussion

The simulation output enables the establishment of relationship patterns between different system variables and their performance parameters through a correlation analysis. The AHP method establishes outcome weightage through a process that leads to k-means clustering for determining optimal input values for system improvement.

Simulation analysis

The vertical velocity and temperature distribution for different chimney angles are presented in Fig. 4a,b respectively. This shows the flow and gradient dynamics change with convergence of chimney. The velocity profiles represent the impact of chimney expansion on buoyancy-driven flow, velocity gradients, and potential flow separation while the temperature gradient helps in understanding the temperature variations in the chimney. A perfect optimizing chimney design becomes possible through this method to boost thermal plume performance and passive cooling functionality.

This section presents the vertical velocity distribution for conical chimneys with different inclination angles (0°, 2°, 5°, 6°, and 8°). The study examines how the angle affects flow velocity at different sections, including the inlet, middle, and outlet, determining the optimal design for maximizing natural convection. The velocity trends help assess airflow efficiency, with the highest velocity at the outlet indicating the best performance. For θ = 0°, the chimney is cylindrical, leading to minimal acceleration of airflow. The velocity remains low across the section, with the highest value at the outlet being 0.0351 m/s. The absence of convergence limits buoyancy-driven acceleration, reducing the effectiveness of thermal plume formation33. At θ = 2°, a slight divergence allows for improved airflow, leading to increased velocity at the middle and outlet sections. The outlet velocity rises to 0.0531 m/s, showing a better convective effect than the 0° case. However, the airflow is still constrained, and the velocity gain remains moderate.

For θ = 5°, the chimney structure enhances the chimney effect significantly, increasing velocity at the middle to 0.0543 m/s and at the outlet to 0.1497 m/s. The conical shape assists in better acceleration of heated air, improving natural convection efficiency. At θ = 6°, a further increase in inclination leads to greater velocity gains, reaching 0.2655 m/s at the outlet. The middle section velocity is also higher at 0.0643 m/s, indicating a strong thermal plume effect. This suggests an optimized airflow profile for passive cooling applications34. For θ = 8°, the velocity is maximized, with an outlet velocity of 4.3328 m/s, significantly surpassing previous configurations. The converging design accelerates airflow efficiently, ensuring optimal heat dissipation and buoyancy-driven flow. This makes 8° the optimal design, as it enhances natural convection, minimizing energy losses while maximizing cooling efficiency.

The temperature distribution across different conical chimney configurations (θ = 0°, 2°, 5°, 6°, and 8°) represents the impact of divergence angles on thermal performance. These variations influence buoyancy-driven convection and heat transfer, ultimately determining the optimal chimney design for effective passive cooling35. The straight cylindrical design lacks convergence at θ = 0°, leading to minimal airflow acceleration. Heat accumulates at the base, with an inlet temperature of 404.92 K and an outlet temperature of 572.99 K. The lack of expansion results in poor convective heat transfer, causing inefficient exhaust of hot air and limited temperature reduction along the chimney height36. A slight divergence improves airflow, reducing thermal stagnation at θ = 2°. The inlet temperature slightly increases to 405.73 K, while the middle section cools to 328.63 K, showing better thermal dissipation than the 0° case. However, the outlet temperature drops drastically to 313.83 K, indicating that while air is expelled efficiently, the buoyancy effect is still not fully optimized.

With further divergence, buoyancy forces increase, accelerating hot air evacuation at θ = 6°. The inlet temperature remains stable at 403.36 K, while the middle section drops to 321.25 K, showing improved cooling efficiency. The outlet temperature increases slightly to 313.23 K, indicating enhanced thermal plume development, but not yet achieving peak performance. The 8° divergence proves optimal, as the chimney structure enables the highest heat recovery. The inlet temperature reaches 410.72 K, facilitating rapid airflow acceleration due to higher buoyancy forces. The middle section retains 328.47 K, while the outlet reaches 318.22 K, marking efficient heat dissipation and superior thermal plume dynamics. This configuration maximizes airflow velocity and temperature gradients, ensuring optimal passive cooling37. The 8° conical angle enables the highest recoverable temperature due to enhanced pressure differentials and buoyancy-driven acceleration.

To conduct a thorough comparative study with the simulation CFD model, curves have been plotted which validate the influence of the inclination angle on the evolution of velocity and temperature. This is represented in accordance with the maximum values of these quantities (V and T) at key points. This approach clearly establishes 8 degrees as the optimal angle which exhibits the highest velocity and heat recovery at all levels. Ten evolution curves—five for velocity and five for temperature are plotted. The negative velocity sign at the inlet (20 mm) is justified by the recirculation observed at this location, as shown in the Fig. 5. Additionally, it is evident that the evolution of performance and efficiency is not linear with an increasing inclination angle. This is further supported by the behaviour at 6°, reinforcing the optimal status of the 8° angle.

The SCPP operates on the principle of buoyancy-driven airflow, where heated air rises through the chimney to drive a turbine for power generation38. The useful power output is estimated based on the temperature-induced air movement, which directly correlates with the total heat transfer rate. At a 0° angle, the inlet heat is 3.343 W, and the outlet heat is 9.023 W, indicating limited airflow acceleration. As the chimney angle increases, the outlet heat first fluctuates and then gradually rises, demonstrating improved heat transfer. At 8°, the inlet heat reaches 3.376 W, while the outlet heat surges to 13.499 W, marking the highest thermal energy extraction due to enhanced airflow velocity and temperature gradients.

A higher chimney angle facilitates greater thermal energy generation by enhancing convective heat transfer and reducing thermal resistance within the system39. The 8° divergence enables optimal flow expansion, leading to higher buoyancy forces that accelerate hot air evacuation. This maximizes kinetic energy conversion, improving power generation potential. Additionally, the increased angle reduces backflow losses and maintains a stable temperature gradient along the chimney height, ensuring sustained heat transfer40. Thus, 8° is the ideal angle for optimizing both heat transfer efficiency and buoyancy-driven airflow, making it the most effective design for SCPP performance.

Figure 5 illustrates how increasing chimney inclination angle enhances both velocity and temperature gradients across the collector radius, with the 8° configuration yielding the highest airflow (V) and temperature (T) peaks. This results in improved natural convection and thermal buoyancy, as a steeper inclination facilitates more efficient vertical air movement, boosting system performance. The observed trends validate the study’s core hypothesis that optimal geometric tuning directly elevates thermal and flow efficiency in hybrid solar chimney systems, thus improving both electricity and hydrogen production potential.

Correlation analysis

The Pearson’s r correlation analysis quantifies important relationships to support optimized chimney design which improves heating efficiency and airflow output. The analysis helps to identify essential variables which optimize power output alongside the hydrogen generation efficiency as observed in Fig. 6.

The turbine pressure drop shows a moderate to high correlation with chimney inclination (Pearson’s r = 0.5804, Adj R2 = 0.3002), indicating that increasing the chimney angle enhances pressure variation due to buoyancy effects. Similarly, pressure drop has a strong positive correlation with collector absorptivity (r = 0.8186, Adj R2 = 0.4678) since higher absorptivity improves heat transfer, leading to stronger buoyancy forces. However, its correlation with solar radiation is weak (r = 0.0261, Adj R2 = 0.0542), suggesting that short-term fluctuations in solar input do not significantly influence pressure variation. Airflow velocity exhibits a strong correlation with chimney inclination (r = 0.6593, Adj R2 = 0.4041) as a steeper angle improves convective heat transfer, accelerating air movement. It also correlates positively with pressure drop (r = 0.9768, Adj R2 = 0.9517) because higher pressure gradients drive faster airflow. The correlation with solar radiation is moderate (r = 0.5319, Adj R2 = 0.3243), meaning increased radiation contributes to air velocity but is not the sole determining factor.

The power output strongly correlates with airflow velocity (r = 0.9815, Adj R2 = 0.9619), proving that higher airflow directly enhances turbine performance. The correlation with pressure drop is also high (r = 0.9768, Adj R2 = 0.9517), as stronger buoyancy forces result in greater energy conversion. However, its relationship with solar radiation (r = 0.5348, Adj R2 = 0.2936) is moderate, emphasizing that consistent airflow and chimney efficiency matter more than solar intensity variations alone. Hydrogen generation has the highest correlation with power output (r = 0.9959, Adj R2 = 0.9913), demonstrating that increased power availability directly boosts electrolysis efficiency. Its correlation with airflow velocity (r = 0.9944, Adj R2 = 0.9882) and pressure drop (r = 0.9812, Adj R2 = 0.9619) is also very strong, showing that optimal thermal and flow conditions maximize hydrogen production. However, it has a moderate correlation with collector absorptivity (r = 0.7520, Adj R2 = 0.5144) and solar radiation (r = 0.6288, Adj R2 = 0.3619), suggesting that while solar input influences generation, system efficiency is more dependent on airflow and pressure variations.

Priority analysis

The findings from AHP analysis need to be prioritized for determining dominant outcomes which supports accurate clustering operations in the k-means method. The system optimization process becomes more effective through emphasis on key performance factors which is illustrated in Fig. 7.

A conical chimney system depends primarily on power output as its main determinant factor since chimney inclinations drive efficient buoyancy airflow which increases turbine efficiency which is in accordance with the obtained weightages (47.09%). Moreover, hydrogen generation (28.40%) ranks second best due to its direct relationship among power output and electrolysis efficiency. Airflow velocity receives weightage of 17.15% but it plays an important role in energy conversion owing to its connection to pressure drop limitations. The weightage for turbine pressure drop (7.36%) is minimal primarily due to advanced conical chimney designs are responsible for reduction in airflow resistance leading to better efficiency. The energy generation optimization from the conical design stems from a well-balanced weighting system between thermal dynamics and aerodynamic functions and electrochemical activities.

Power output received the dominant weight because it represents the primary conversion of solar thermal energy into usable electricity, which is the core mechanism driving the entire hybrid system, with all downstream processes (including electrolysis for hydrogen generation) being directly dependent on the quantity and stability of electrical output. Power output acts as the bottleneck for the subsequent hydrogen generation process, since the efficiency and rate of hydrogen production via electrolysis are tightly linked to the magnitude and continuity of available electrical power. Airflow velocity, though critical for maximizing natural convection and turbine efficiency, serves as an upstream enabler rather than a fundamental output; its influence, while strong, is indirect compared to power.

k-means clustering analysis

Machine learning processing generates clusters of performance parameters to classify datasets into best, worst and average categories enabling a systematic method for system efficiency assessment. The analysis of the top-performing cluster will reveal essential patterns together with conditions that produce maximum output. The dataset achieving closest proximity to the best cluster center will be selected because it would maximize the performance of system in regarding power output alongside airflow velocity and hydrogen generation levels.

The heatmap dendrogram in Fig. 8 shows cluster distance variations which represent performance shifts because of differences in chimney angle and solar radiation variation. The best performance is achieved in Cluster 1 since impact of chimney angle provides optimal conditions for maximizing solar energy collection and buoyancy-driven ventilation. The performance variables from Cluster 2 fall into the average level indicating insufficient configuration of either chimney angle position or solar radiation exposure. Performance within Cluster 3 (worst) remains at the lowest level because excessive or insufficient chimney inclinations decrease airflow speed and thermal energy efficiency. The many variations in clusters indicate that proper optimization of both chimney structure and solar access is essential for maximizing energy conversion results.

The machine learning analysis divided the datasets into three clusters according to performance metrics which allowed the distinction of best, worst and average performance groups. Among them, datasets 4, 16, and 10 were found closest to the best cluster centroid. Dataset 16 shared the shortest centroidal distance which placed it as the most optimal solar chimney condition point according to Fig. 9. Under the optimal conditions of Chimney Inclination (8°), Solar Radiation (800 W/m2), and Collector Absorptivity (0.88), the system achieved a Turbine Pressure Drop of 95 Pa, Airflow Velocity of 9.8 m/s, Power Output of 16.1 kW, and Hydrogen Generation of 0.62 kg/day. This dataset ensures a high-efficiency balance while maintaining practical feasibility for large-scale applications.

Although dataset 4 exhibits slightly better power output compared to dataset 16, its higher cost makes it less practical for real-world implementation. The increased cost is attributed to its more complex structural modifications, requiring a larger or more aerodynamically optimized chimney, which demands higher material and fabrication expenses. Additionally, improved thermal insulation and enhanced collector materials in dataset 4 lead to higher absorptivity but also increase manufacturing and operational costs. Dataset 16, on the other hand, achieves an optimal balance between power generation and cost efficiency, making it the most viable choice for maximizing energy conversion while maintaining economic feasibility in solar chimney applications.

The hybrid analysis derived results enable groupings of operational scenarios with similar performance characteristics. Each cluster delineates a distinct regime in the multi-parameter design space, enabling targeted optimization by highlighting parameter combinations that yield comparable energy conversion efficiencies and sustainable hydrogen production rates. This clustering allows for systematic decision-making and prioritization of design variables, facilitating the identification of optimal system configurations while reducing computational complexity by focusing on representative clusters rather than individual data points.

Discussion

The performance of the system depends on collector absorptivity according to Fig. 10. The performance of turbine pressure drop and hydrogen generation shows an irregular pattern when collector absorptivity increases because changes in heat absorption and airflow dynamics affects the thermal updraft. This further determines airflow velocity through absorptivity as improved convective currents occur with high absorptivity but turbulence introduces flow non-uniformity effects. A power decline occurs until an optimal heat retention point where higher absorptivity leads to power output growth in the system. The system efficiency benefits from maximal solar absorptivity yet excessive values might lead to thermal losses which degrade stability.

As depicted in Fig. 11, an increment in the applied solar radiation certainly effects the system variables primarily due to improved thermal energy absorption. High values of applied radiation boost the airflow velocity by growing the temperature gradient, enabling a stronger buoyancy-driven current. This further translates into a higher turbine pressure drop, which eventually improves airflow in the converging section design of chimney, boosting power output. Subsequently, hydrogen production simultaneously upsurges due to enhanced system efficiency and energy conversion. Nevertheless, at decreased levels of solar radiation, reduced thermal input fades this effect, leading to lower velocity, pressure drop, and total hydrogen creation capacity.

The Fig. 12 displays that increment in chimney inclination angle boosts the combined outcomes of the study. As the inclination surges from 2° to 8°, airflow velocity simultaneously boosts significantly enabling an improved buoyancy-driven flow, attaining approximately 9.8 m/s at 8°. This enhanced airflow increases the turbine pressure drop from nearly 80 Pa to 95 Pa, enabling improved energy conversion. Accordingly, power output progresses from around 12 kW to 16.1 kW as more kinetic energy is available from increased velocity. The hydrogen production follows a similar trend, increasing from about 0.4 kg/day to 0.62 kg/day, directly correlating with power output, as higher electricity availability advances electrolysis efficiency. This validates the optimal selection of 8-degree angle which maximizes the performance variables.

The simplified model excludes critical components such as the solar collector’s detailed geometry, ground heat storage, and ambient environmental variations, all of which profoundly influence turbulence, thermal gradients, and pressure distributions in operational conditions. This results in an idealized flow representation that neglects transient effects, multi-directional wind impacts, and heat loss mechanisms present in full-sized power plants. Moreover, complex interactions between multiple system components and materials’ thermal responses in real large-scale setups may introduce nonlinearities and instabilities not captured in the simplified framework. Consequently, predicted performance outcomes may be over-optimistic or lack fidelity under variable climatic and structural stressors. Thus, while excellent for isolating chimney shape effects and foundational design optimization, the simplified model requires coupling with more comprehensive, multi-physics simulations or scaled experiments to robustly translate results to practical, large-scale SCPP deployment scenarios, accounting for real-world operational heterogeneities and long-term sustainability factors.

The current study’s results align well with previous research demonstrating comparable performance metrics for solar chimney power plants. Cuce et al.41 reported power outputs near 46.6 kW for similar solar radiation intensity and collector dimensions, showing consistent airflow velocity and pressure drop profiles with our findings. Similarly, Mandal et al.42 explained the importance of chimney geometry and solar radiation interplay, corroborating the observed impact of chimney inclination and absorptivity on system efficiency and power output. These parallels validate the modelling approach used in this study while reinforcing the significance of multi-objective optimization for hybrid electricity and hydrogen generation systems. These studies collectively affirm the current work’s reliability and extend its outcome relevance in the solar chimney power plant literature.

Conclusions

The research investigates conical solar chimney thermal processes and airflow mechanisms to improve its functionality when generating electrical power and hydrogen. Different angles for the chimney system were used to boost both buoyant airflow strength and heat exchange effectiveness. AHP enables decision making by allocating importance levels to key parameters one step at a time starting from pressure drop and airflow velocity and power output levels. The identified weighted parameters go through k-means clustering which produces dominant performance patterns. The methodology enables efficient classification of chimney designs through which the best design choice emerges. The combination of AHP with k-means enables the study to balance thermal operations with aerodynamics which results in better energy generation and hydrogen production effectiveness. The system efficiency determining parameters emerged through the integration of AHP priority with k-means clustering methods. The following are the conclusions of the study:

-

At an 8° chimney angle, the inlet heat is 3.376 W, and the outlet heat reaches 13.499 W, maximizing thermal energy extraction, airflow velocity, and power generation efficiency.

-

Hydrogen generation has the highest correlation with power output (r = 0.9959), while power output strongly depends on airflow velocity (r = 0.9815).

-

Power output (47.09%) is the most influential factor, followed by hydrogen generation (28.40%), airflow velocity (17.15%), and turbine pressure drop (7.36%), enhancing the conical chimney’s efficiency.

-

Dataset 16 is the optimal configuration with Chimney Inclination (8°), Solar Radiation (800 W/m2), Collector Absorptivity (0.88), Turbine Pressure Drop (95 Pa), Airflow Velocity (9.8 m/s), Power Output (16.1 kW), and Hydrogen Generation (0.62 kg/day).

The research omits consideration of immediate environmental changes in wind speeds and ambient temperature changes since these factors might impact system functionality. These factors directly affect buoyancy-driven flow stability and turbulence intensity, leading to fluctuating power. Additionally, neglecting long-term material degradation, especially in chimney structural integrity, might result in diminished heat capture efficiency and increased thermal losses, reducing overall system efficiency and lifespan. These unaccounted dynamic and degradation effects could compromise the sustainable performance and economic viability of the proposed system when subject to aging stresses. Another potential limitation includes lack of integration with thermal energy storage systems such as phase change materials, which could enhance performance by mitigating solar intermittency and providing more stable, continuous power and hydrogen production. Additionally, while k-means clustering effectively identifies operational regimes, it has inherent limitations for real-world decision-making due to its reliance on predefined clusters. Unlike advanced multi-objective optimization algorithms like NSGA-II, k-means does not generate Pareto-optimal solutions or consider trade-offs explicitly, potentially restricting its ability to address complex, multi-criteria design goals.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- SCPP:

-

Solar chimney power plant

- ANSYS Fluent:

-

Analysis system fluent

- k-means:

-

Machine learning algorithm for clustering

- AHP:

-

Analytic hierarchy process

- WCSS:

-

Within-cluster sum of squares

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- CFD:

-

Computational fluid dynamics

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- Re:

-

Reynolds number

- Pearson-r:

-

Pearson correlation coefficient

- W/m:

-

Watts per square meter

- Pa:

-

Pascal

- m/s:

-

Meters per second

- kW:

-

Kilowatt

- kg/day:

-

Kilogram per day

- V:

-

Airflow velocity

- Pt :

-

Turbine pressure drop

- ηt :

-

Turbine efficiency

- m:

-

Mass flow rate

- g:

-

Gravitational acceleration

- h:

-

Height of chimney

- A:

-

Turbine cross-sectional area

- Pelec :

-

Electrical power input

- H:

-

Enthalpy change

- L:

-

Chimney length

- r0, r1, r2 :

-

Radii: heat source radius, inlet radius, outlet radius

- Cd :

-

Discharge coefficient

- T, Te, Tn :

-

Temperature: general, experimental, numerical

- Vr, vz :

-

Velocity components in radial and axial directions

- Q:

-

Number of clusters in k-means clustering

- Pq :

-

Number of data points in cluster q

- yr :

-

Coordinates of data point r in cluster q

- Q:

-

Centroid of cluster q

- Tw :

-

Wall temperature

- T0 :

-

Ambient or inlet temperature

- Pin, Pout :

-

Pressure at inlet and outlet

- V:

-

Kinematic viscosity

- P:

-

Pressure

- Cp :

-

Specific heat capacity at constant pressure

- G:

-

Turbulence production

- C1, C2 :

-

Empirical constants

- xj :

-

Spatial coordinate

- vk :

-

Velocity component

- τ:

-

Shear stress tensor or turbulence time scale

- r, z:

-

Cylindrical coordinates: radial and axial directions

- Vmax :

-

Maximum airflow velocity observed

- Tinlet, Toutlet :

-

Temperatures at chimney inlet and outlet

- ΔP:

-

Pressure difference

- r2, r3 :

-

Exponents indicating squared, cubed terms

References

Dhahri, A. & Omri, A. A review of solar chimney power generation technology. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2 (3), 1–17 (2013).

Danook, S. H., AL-bonsrulah, H. A. Z., Hashim, I. & Veeman, D. CFD simulation of a 3D solar chimney integrated with an axial turbine for power generation. Energies 14, 5771 (2021).

Mohammadi, F., Jahangiri, A. & Ameri, M. Thermo-Enviro-Exergoeconomic Analysis of Solar Chimney Compared with Heller Tower in Fars Combined Cycle Power Plant 100506 (Energy Nexus, 2025).

Fluri, T. P. & von Backström, T. W. Comparison of modelling approaches and layouts for solar chimney turbines. Sol. Energy. 82 (3), 239–246 (2008).

Guo, P., Li, J., Wang, Y. & Wang, Y. Numerical study on the performance of a solar chimney power plant. Energy. Conv. Manag. 105, 197–205 (2015).

Abdelsalam, E., Almomani, F., Alnawafah, H., Habash, D. & Jamjoum, M. Sustainable production of green hydrogen, electricity, and desalinated water via a hybrid solar chimney power plant (HSCPP) water-splitting process. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 52, 1356–1369 (2024).

Jemli, M. R., Naili, N., Farhat, A. & Guizani, A. Experimental investigation of solar tower with chimney effect installed in CRTEn. Tunisia Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 42 (13), 8650–8660 (2017).

Shariatzadeh, O. J., Refahi, A. H., Abolhassani, S. S. & Rahmani, M. Modeling and optimization of a novel solar chimney cogeneration power plant combined with solid oxide electrolysis/fuel cell. Energy. Conv. Manag. 105, 423–432 (2015).

Araya, H. G. & Teferi, S. T. Performance comparison of cylindrical and diverging solar chimney power plants. Results Eng. 105485 (2025).

Habibollahzade, A. et al. Enhanced power generation through integrated renewable energy plants: solar chimney and waste-to-energy. Energy. Convers. Manag. 166, 48–63 (2018).

Fasel, H. F., Meng, F., Shams, E. & Gross, A. CFD analysis for solar chimney power plants. Sol. Energy. 98, 12–22 (2013).

Habash, D. et al. Green hydrogen: a novel hybrid solar chimney power plant integrated with electrolysis station. In 2023 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), 1–6 (IEEE, 2023).

Yahya, Z. & Mahmoud, A. M. Numerical study of the effects of a hot obstacle on natural convection flow regimes. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 16 (3), 459–476. https://doi.org/10.47176/jafm.16.03.1339 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. Optimal design of large-scale solar-aided hydrogen production process via machine learning based optimisation framework. Appl. Energy. 305, 117751 (2022).

Abdelsalam, E. et al. A classifier to detect best mode for solar chimney power plant system. Renew. Energy. 197, 244–256 (2022).

Smaisim, G. F., Abed, A. M. & Shamel, A. Modeling the thermal performance for different types of solar chimney power plants. Complexity 2022 (1), 3656482 (2022).

Abdelsalam, E., Almomani, F. & Ibrahim, S. A novel hybrid solar chimney power plant: performance analysis and deployment feasibility. Energy Sci. Eng. 10 (9), 3559–3579 (2022).

Fallah, S. H. & Valipour, M. S. Numerical investigation of a small scale sloped solar chimney power plant. Renew. Energy. 183, 1–11 (2022).

Mehranfar, S. et al. Comparative assessment of innovative methods to improve solar chimney power plant efficiency. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 49, 101807 (2022).

Saleh, M. J., Atallah, F. S., Algburi, S. & Ahmed, O. K. Enhancement methods of the performance of a solar chimney power plant. Results Eng. 101375 (2023).

Abdelsalam, E. et al. Performance analysis of hybrid solar chimney–power plant for power production and seawater desalination: A sustainable approach. Int. J. Energy Res. 44 (14), 11349–11363 (2020).

Roy, D. & Samanta, S. A solar-assisted power-to-hydrogen system based on proton-conducting solid oxide electrolyzer cells. Renew. Energy. 220, 119562 (2023).

Mahmoud, A. M. & Yahya, Z. Experimental investigation of a thermal plume’s air entrainment in a circular cone. Int. J. Thermofluid Sci. Technol. 8 (4), Paper080403 (2021). http://ijtf.org/2021/experimental-investigation-of-a-thermal-plumes-air-entrainment-in-a-circular-cone

Kallioğlu, M. A., Avcı, A. S., Yılmaz, A. & Karakaya, H. A genetic programming approach for the prediction of solar chimney power plant power. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy. 238(2), 322–333 (2024).

Al-Kayiem, H. H. & Aja, O. C. Historic and recent progress in solar chimney power plant enhancing technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 58, 1269–1292 (2016).

Sangi, R., Amidpour, M. & Hosseinizadeh, B. Modeling and numerical simulation of solar chimney power plants. Sol. Energy. 85 (5), 829–838 (2011).

Shahreza, A. R. & Imani, H. Experimental and numerical investigation on an innovative solar chimney. Energy. Conv. Manag. 95, 446–452 (2015).

Ming, T., de Richter, R. K., Meng, F., Pan, Y. & Liu, W. Chimney shape numerical study for solar chimney power generating systems. Int. J. Energy Res. 37 (4), 310–322 (2013).

Arslan, A. E., Arslan, O. & Kandemir, S. Y. AHP–TOPSIS hybrid decision-making analysis: Simav integrated system case study. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 145 (3), 1191–1202 (2021).

Yagmur, L. Multi-criteria evaluation and priority analysis for localization equipment in a thermal power plant using the AHP (analytic hierarchy process). Energy 94, 476–482 (2016).

Khan, F. et al. Innovative hydrogen production from waste bio-oil via steam methane reforming:an advanced ANN-AHP-k-means modelling approach using extreme machine learning weighted clustering. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 105, 1080–1091 (2025).

Khan, O., Alsaduni, I., Parvez, M. & Yadav, A. K. Enhancing hydrogen production using solar-driven photocatalysis with biosynthesized nanocomposites: A hybrid machine learning approach towards enhanced performance and sustainable environment. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 102, 609–625 (2025).

Mokrani, O. B. E. K., Ouahrani, M. R., Sellami, M. H. & Segni, L. Experimental investigations of hybrid: geothermal water/solar chimney power plant. Energy Sour. Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 46 (1), 15474–15491 (2024).

Biswas, N., Mandal, D. K., Bose, S., Manna, N. K. & Benim, A. C. Experimental treatment of solar chimney power plant—A comprehensive review. Energies 16 (17), 6134 (2023).

Arefian, A. & Hosseini Abardeh, R. Ambient crosswind effect on the first integrated pilot of a floating solar chimney power plant: experimental and numerical approach. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 1–19 (2021).

Torabi, M. R. et al. Investigation the performance of solar chimney power plant for improving the efficiency and increasing the outlet power of turbines using computational fluid dynamics. Energy Rep. 7, 4555–4565 (2021).

Kassaei, F., Bagherzadeh, A., Abedi, M. & Bénard, A. Experimental studies of solar chimneys: A survey of performance, design, and applications for power generation. Energies. 18 (17), 4634 (2025).

Ali, M. H., Kurjak, Z. & Beke, J. Modelling and simulation of solar chimney power plants in hot and arid regions using experimental weather conditions. Int. J. Thermofluids. 20, 100434 (2023).

Abdelsalam, E. et al. Integrating solar chimney power plant with electrolysis station for green hydrogen production: A promising technique. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 52, 1550–1563 (2024).

Abdelsalam, E. et al. Synergistic energy solutions: solar chimney and nuclear power plant integration for sustainable green hydrogen, electricity, and water production. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 186, 756–772 (2024).

Cuce, E. Dependence of electrical power output on collector size in Manzanares solar chimney power plant: an investigation for thermodynamic limits. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 17, 1223–1231 (2022).

Mandal, D. K. et al. Optimization of hybrid solar chimney power plants (HSCPPs): A review of multi-objective approaches. Appl. Energy. 396, 126214 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Deanship of Scientific Research, (DSR), Majmaah University, Al Majmaah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, under project number, R-2025-2067.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Symbiosis International (Deemed University). Open access funding provided by Symbiosis International (Deemed University) Pune, India.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.J.: Conceptualization, writing-original draft. Z.Y.: Formal investigation, data curation, software. O.D.: Software, validation, A.M.M.: Methodology, resources. A.A.: Writing-review and editing, V.A.: Funding acquisition, writing-review and editing. O.K.: Data curation, formal analysis. A.K.Y.: Conceptualization, supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jemal, A., Yahya, Z., Drame, O. et al. Optimization of hybrid solar chimney power plant using Pearson and k-means analysis for green hydrogen and electricity production. Sci Rep 15, 40729 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24507-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24507-5