Abstract

Daisy mandarin is a commercially important cultivar of citrus, well known for its superior fruit quality and adaptability to subtropical climates. However, the fruit splitting and imbalances in leaf nutrient content often limits its productivity. To address this issue, a field experiment was carried out during 2021 and 2022 at the Fruit Research Station, Jallowal-Lesriwal, Jalandhar, to evaluate the influence of different growth regulators on the incidence of fruit splitting and leaf nutrient composition of Daisy mandarin budded on two rootstocks viz., Rough lemon and Carrizo Citrange. Maintaining the optimal foliar nutrient status is essential, as it plays a vital role in sustaining tree vigor, development of fruits and overall yield. This study involved the foliar application of gibberellic acid (GA3) at 10, 20 and 30 ppm, naphthalene acetic acid (NAA) at 10, 20 and 30 ppm; ethephon at 10, 20 and 30 ppm; and salicylic acid (SA) at 100 and 200 ppm concentration, applied at different phenological stages. The trial was conducted on Daisy mandarin trees budded on two different rootstocks i.e. Rough lemon and Carrizo citrange. Fruit splitting was observed to be more pronounced in Carrizo citrange rootstock than in Rough lemon, which may be attributed to higher soluble solids accumulation, weaker anatomical structure, and greater stress susceptibility. The pooled analysis over two consecutive years revealed that foliar application of SA at 100 ppm significantly reduced the fruit splitting incidence (3.14% and 3.60%) and enhanced the concentrations of nitrogen (2.65% and 2.66%), phosphorous (0.15% and 0.16%), potassium (1.65%), calcium (3.58% and 3.52%), magnesium (0.35%), and other micro nutrient content of Daisy mandarin in the leaves followed by other growth regulators as compared to other untreated (control) plants. These results suggest that SA at 100 ppm is a promising foliar treatment for improving the nutritional status of Daisy mandarin in the subtropical conditions of Punjab.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Citrus is one of the most widely cultivated fruit crops worldwide, valued for its distinctive fruit size, color, flavor and abundance of phyto-chemicals with therapeutic and nutraceutical properties1,2. Globally citrus ranks as the third most important fruit crop in terms of area and production, following mango and banana. The major commercially cultivated citrus species include sweet orange, grapefruit, mandarin and lemon, all of which are integral to both the fresh fruit market and the processing industry3. In India, citrus stands as the third most important fruit crop cultivated on 1100.43 thousand hectares and producing 14.61 million metric tonnes annually4. Among the major growing regions, Punjab is recognized for its high quality citrus production. Citrus cultivate on in Punjab covers 54.99 thousand hectares, yielding an annual production of 1.34 million metric tonnes5. In India, Mandarin, particularly are highly preferred among the Indian consumers due to their ease of peeling, high juice content and pleasant flavor. The northwestern part of Indian is especially renowned for Kinnow mandarin, a hybrid that has gained international recognition6,7. Mandarin’s cultivation has emerged as a profitable crop for fruit growers, offering a higher economic returns in comparison to many other horticultural crops3,8. Among the commercially important cultivars, Daisy mandarin (Citrus reticulata Blanco), has gained attention as a newly introduced variety, distinguished by its early ripening, unique fruit coloration and superior fruit quality. Currently, Daisy mandarin accounts for approximately 15% of the total citrus production in the region. Field evaluations indicate that this cultivar performs well on Rough lemon rootstock under the arid irrigated conditions of Punjab and is also compatible with the Carrizo citrange rootstock, particularly in soils with pH values below 8.03. However, despite its agronomic and commercial potential, Daisy mandarin is highly susceptible to fruit splitting, a physiological disorder that poses a major challenge in citrus production worldwide. This prevalent physiological disorder affects more than 60 per cent of global citrus production. This disorder accounts for substantial economic losses and is often triggered by abrupt changes in environmental conditions such as sudden rainfall after drought, uneven supply of fertilizers and water stress. Apart from this, other factors including cultivar, rootstock compatibility, weather extremes, peel hardness, hardiness, growth regulators and nutrient imbalances (lower Calcium, potassium and high Phosphorous) and heavy crop load during fruit development can also cause fruit splitting in some citrus cultivars9,10.

The role of mineral nutrition in citrus physiology is well established, specifically in terms of vegetative growth, fruit set, quality and stress tolerance. Daisy mandarin, like other citrus species, is largely dependent on adequate mineral nutrition. Daisy mandarin, predominantly grown in the alluvial soils of Punjab, showed higher sensitivity to such nutritional disorders, which are further influenced by soil pH and rootstock compatibility11. Conventional soil fertilization often falls short due to nutrient losses and limited uptake efficiency, thereby necessitating alternative strategies for nutrient management. Macronutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium along with secondary nutrients like calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) are essential for critical physiological processes including photosynthesis, osmotic regulation, fruit development and stress resilience12,13. Leaf nutrient analysis has been established as a reliable tool to assess the nutrient status of citrus stress14. In the recent years, plant growth regulators (PGRs) have gained attention for their role in mitigating abiotic and physiological disorders in fruit crops. Exogenous application of PGRs like GA3, NAA, ethephon and SA have been reported to influence key physiological processes including root activity, improve nutrient translocation and increases the stress tolerance. Exogenous application of PGRs at critical phenological stages can positively enhanced the leaf nutrient content and mitigate the physiological disorder such as fruit splitting and modifying the nutrient portioning within the plant10,15.

However, despite growing interest, there is limited knowledge is available with regards to the role of growth regulators in mitigating the fruit splitting and improving the leaf nutrient content of Daisy mandarin under subtropical conditions. Therefore, the present study was carried to investigate the influence of foliar application of different concentrations of growth regulators on the incidence of fruit splitting incidence and leaf nutrient content in Daisy mandarin budded on two rootstocks-Rough lemon and Carrizo citrange-under the subtropical climatic conditions of Punjab.

Materials and methods

Experimental site and planting material

The present experiment was undertaken to evaluate the nutritional status of leaves of Daisy mandarin (Citrus reticulata Blanco) budded on two rootstocks Rough lemon (Citrus jambhiri Lush) and Carrizo citrange, during the years 2021 and 2022. The study was carried out at the Fruit Research Station, Jallowal-Lesriwal, Jalandhar, Punjab Agricultural University (PAU), Ludhiana, Punjab, India. The experimental site is situated at an elevation of 228 m above mean sea level and is geographically located at 31°29ʹ38ʺ N latitude and 75°37ʹ40ʺ E longitude. The experimental site was characterized by sandy loam soils with a pH ranging from neutral to alkaline. The nutrient profile of the soil revealed moderate levels of nitrogen, whereas potassium was found to be deficient. Similarly, the availability of micronutrients was also inadequate. The soils exhibited a low organic matter content, which further limits their fertility status (Table 1).

Experimental design and methodology

The experimental layout followed a randomized complete block design (RCBD), with each treatment replicated three times. The plant material comprised of 8-year-old Daisy mandarin trees, budded onto the respective rootstocks and spaced at 6 × 3 m. Trees selected for sampling were uniform in terms of age, canopy size, shape, and vigor to reduce variability associated with plant heterogeneity. The leaves and fruit sample and leaves from the selected trees were collected randomly by using citrus clippers. Sampling was conducted during the morning hours in the months of August and September to ensure consistency. The collected samples were then immediately transported to the PG and nutritional laboratories, Department of Fruit Science, PAU, Ludhiana, for further laboratory analysis. Standard horticultural practices, including irrigation, fertilization, and manuring and plant protection measure were uniformly applied across all the experimental units throughout the duration of the study to maintain consistent growing conditions across treatments.

Treatment details

The following table provides the details of treatments applied.

Treatment application

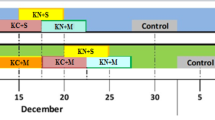

Treatment solutions were applied to the foliage using a battery-operated Knapsack sprayer until the point of runoff, ensuring uniform coverage of the tree canopy. The spray solutions for different treatments were prepared at the desired concentrations by dissolving the required quantities of the respective chemicals in water (e.g., 10 ppm, equivalent to 50 mg in 5 L of water per tree). Each tree received 5 L of solution, applied with a hand-operated knapsack sprayer of 15 L capacity to ensure uniform and thorough foliar coverage. The same procedure was followed for the preparation and application of all other treatments. Foliar sprays were carried out during 2021 and 2022 growing season at three critical phenological stages: once fruit set stage, 30 and 60 DAFS during 2022 (Table 2). Each treatment was replicated three times to ensure the statistical reliability and reproducibility of the results. All spraying operations were carried out during the morning hours, between 7 and 9 am, to minimize the potential negative effects of high temperatures and wind speed, which could otherwise compromise the foliar absorption efficiency.

Observations recorded

Fruit splitting incidence (%)

The incidence of fruit splitting was recorded by counting the total number of fruits per tree from 90 DAFS until harvest (210 DAFS), during both the years 2021 and 2022. The number of split fruits was recorded at monthly intervals. The percentage of fruit splitting was calculated by using the following formula:

Leaf nutrient analysis (Macro and micro nutrients)

The leaves samples from Daisy mandarin plants were collected during the morning hours in the months of August and September. The tress were selected based on the uniformity in canopy size, shape, age and vigor to ensure homogeneity and minimize experimental variability.

Nitrogen estimation (%)

The nitrogen content in leaf tissue was determined by using the Kjeldahl method, as described by20. For this estimation, 500 mg of oven-dried, finely ground leaf sample from each treatment was weighed and placed into the digestion tubes of the Kelpus Nitrogen Estimation (Pelican Equipment, Chennai, India). Then the digestion mixture comprising potassium sulphate (K2SO4) and copper sulphate (CuSO4 .5H2O) was added to the each tube. The samples were then subjected to the digestion at 410 °C. Completion of digestion was indicated by the solution turning into light green or becoming clear.

The digested material was then transferred to the distillation unit. A 40% of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution was added to facilitate the release of ammonium ions (NH4+), which were captured in a conical flask containing 10 mL of 4% boric acid along with mixed indicators. Steam distillation was carried out and the released ammonia was absorbed in the boric acid solution. The resulting distillate was titrate against 0.1 N sulphuric acid (H2SO4). The endpoint of the titration was marked by a color change from pink to light green. The nitrogen content was calculated and expressed as a percentage using the following formula:

Where X = volume of N/10 NaOH used for neutralizing excess of H2SO4.

Determination of phosphorous, potassium, calcium, magnesium and micronutrients

For the estimation of phosphorus (P0, potassium(K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and micronutrients, including iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu), leaf samples were subjected to wet digestion using a triple acid mixture consisting of nitric acid (HNO3), perchloric acid (HCIO4) and sulphuric acid (H2SO4). By following the complete digestion, the samples were diluted and filtered, and the final volume was made upto 100 ml using the double distilled water.

Phosphorous estimation

Phosphorous content was estimated by colorimetrically using the Vanado-molybo phosphoric yellow colour protocol, as described by 21. A series of standard phosphorus solutions (0–5 mL) were prepared in 25 mL volumetric flasks. To each flask, 5 mL of vanadate-molybdate reagent was added, the final volume was adjusted to 25 mL with distilled water. After 30 min of color development, the intensity of the yellow color was measured at 470 nm using a spectrophotometer (Spectronic 20D+, Thermo Scientific, USA). A standard calibration curve was prepared by using the known phosphorus concentrations, and the phosphorus content of the plant samples was extrapolated form this curve.

The phosphorus content was expressed as a percentage using the following formula:

Potassium content in leaf samples was determined by using a flame photometer22. Ca, mg, Fe, Mn, Zn and Cu concentrations were determined by using an Atomic absorption spectrophotometer (A Analyst 200, Perkin Elmer, USA). All the nutrient concentrations were expressed on a dry weight basis.

Boron content

Boron content in leaf samples was determined by using the Azomethine-H method as described by23. For the analysis, 0.5 g dried and ground leaf material was placed in silica crucibles and subjected to dry ashing in a muffle furnace at 550 °C until a grayish-white ash was obtained. The ash was then dissolved in a 10 ml of 6 N hydrochloric acid (KCl) and gently heated to approximately 80 °C on a hot plate to evaporate the acid content. After complete drying, the residue was re-dissolved in distilled water and then transferred to a 25 ml volumetric flask. The volume was then adjusted with distilled water and the solution was filtered through using Whatman filter paper. The boron concentration in the extract was measured colorimetrically using the azomethine-H reagent.

Statistical analysis

The experiment was conducted in a Randomized Block Design consisting of 12 treatments, each replicated three times and each treatment consisted of three plants. The data collected were subjected to two way Analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Statistical analysis software (SAS) version 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The treatment means were compared using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test at a 5% level of significance (p ≤ 0.05) to determine the statistical significance of differences among treatments.

Results

Fruit splitting percentage (%)

The foliar application of growth regulators have a significant effect on the fruit splitting percentage in Daisy mandarin (Fig. 1). The pooled analysis of the given data indicated that the highest fruit splitting was noted in control (untreated) plants during both rootstocks. The highest (13.73% and 13.23) fruit splitting was observed in Carrizo citrange and Rough lemon (13.23%) rootstocks in untreated plants (T12). While the minimum (3.14% and 3.60%) fruit splitting was recorded in Rough lemon and Carrizo citrange plants treated with (T10) SA at 100 ppm concentration during the growing season.

Effect of growth regulators on total fruit splitting percentage of Daisy mandarin budded on Rough lemon and Carrizo citrange. T1 = GA3 10 ppm, T2 = GA3 20 ppm, T3 = GA3 30 ppm, T4 = NAA 10 ppm, T5 = NAA 20 ppm, T6 = NAA 30 ppm, T7 = Ethephon 10 ppm, T8 = Ethephon 20 ppm, T9 = Ethephon 30 ppm, T10 = SA 100 ppm, T11 = SA 200 ppm, T12 = Control.

Macronutrient content of leaves

Nitrogen (N) content (%)

The foliar application of growth regulators showed a significant effect on the nutrient content of leaves of Daisy mandarin across both years of study (Fig. 2). Among the different nutrients, SA 100 ppm resulted in the highest nitrogen concentration in the leaves of plants budded on both Carrizo (2.66%) and Rough lemon (2.65%) rootstocks. This was followed by other growth regulators treatments, whereas the lowest nitrogen content was observed in untreated control plants (T12) in Carrizo citrange (2.45%) and Rough lemon (2.51%) respectively (Fig. 2A).

Effect of growth regulators of leaf macronutrient content of Daisy mandarin i.e. (A) Nitrogen, (B) Phosphorous, (C) Potassium, (D) Calcium, (E) Magnesium. T1 = GA3 10 ppm, T2 = GA3 20 ppm, T3 = GA3 30 ppm, T4 = NAA 10 ppm, T5 = NAA 20 ppm, T6 = NAA 30 ppm, T7 = Ethephon 10 ppm, T8 = Ethephon 20 ppm, T9 = Ethephon 30 ppm, T10 = SA 100 ppm, T11 = SA 200 ppm, T12 = Control.

Phosphorus (P) content (%)

The phosphorus concentration in Daisy mandarin leaves were significantly influenced by the application of growth regulators during the growing season (Fig. 2B). Based on the pooled data across both the years, the highest phosphorous content (0.160% and 0.150%) was recorded in plants budded on Carrizo citrange and Rough lemon rootstocks, following the foliar application of SA at 100 ppm (T10). The lowest phosphorous content (0.118% and 0.115%) was recorded in untreated control plants (T12) on Carrizo citrange and Rough lemon rootstocks, respectively.

Potassium (K) content (%)

The pooled analysis of the studied year revealed that the application of growth regulators had a significant impact on the potassium content of Daisy mandarin leaves (Fig. 2C). Among the different concentrations, the foliar application of SA at 100 ppm (T10) resulted in the highest potassium concentration (1.65%) in leaves of Carrizo citrange and Rough lemon rootstocks. In contrast, the lowest content of potassium was recorded in untreated (control) plants (T12) in Rough lemon (1.39%) and Carrizo citrange (1.46%) rootstocks respectively.

Calcium (Ca) content (%)

The calcium content in leaves of Daisy mandarin was significantly influenced by the foliar application of different growth regulators (Fig. 2D). From the given pooled analysis, it was found that the highest calcium content concentrations were observed in the plants treated with SA at 100 ppm (T10) in Rough lemon (3.58%) and Carrizo citrange (3.52%) rootstocks. While the lowest calcium contents were recorded in the untreated plants (T12) of Carrizo citrange (3.24%) and Rough lemon (3.27%) rootstocks respectively.

Magnesium (Mg) content (%)

The magnesium content of leaves of Daisy mandarin was significantly influenced with the application of growth regulators (Fig. 2E). According to the pooled data, is was noticed that the highest leaf magnesium content was recorded in trees treated with SA at 100 ppm (T10) in Rough lemon (0.354%) and Carrizo citrange (0.348%) rootstocks respectively. Conversely, the minimum Mg content was recorded in Rough lemon (0.341%) and Carrizo citrange (0.339%) in an untreated plants (T12).

Micronutrient content of leaves

Iron (Fe) content (ppm)

The application of growth regulators significantly influenced the iron content in the leaves of Daisy mandarin (Fig. 3A). The pooled analysis of the data indicated that the foliar application of SA at 100 ppm (T10) resulted in the maximum Fe content in leaves of Rough lemon (120.33 ppm) and Carrizo citrange (118.00 ppm) respectively, while the minimum Fe content was recorded in the untreated plants (T12) of Carrizo citrange (101.94 ppm) and Rough lemon (107.25 ppm) rootstock respectively.

Effect of growth regulators of leaf micronutrient content of Daisy mandarin (A) Iron, (B) Manganese (C) Zinc, (D) Copper, (E) Boron, (F) Carbohydrate content. (G) C/N Ratio. T1 = GA3 10 ppm, T2 = GA3 20 ppm, T3 = GA3 30 ppm, T4 = NAA 10 ppm, T5 = NAA 20 ppm, T6 = NAA 30 ppm, T7 = Ethephon 10 ppm, T8 = Ethephon 20 ppm, T9 = Ethephon 30 ppm, T10 = SA 100 ppm, T11 = SA 200 ppm, T12 = Control.

Maganese (Mn) content (ppm)

The manganese content of leaves of Daisy mandarin were significantly influenced with the foliar application of growth regulators (Fig. 3B). From the given pooled analysis, it was noticed that the highest Mn content was recorded in plants treated with SA at 100 ppm (T10), followed by other growth regulators in Rough lemon (27.74 ppm) and Carrizo citrange (25.62 ppm) rootstocks respectively. Conversely, the minimum manganese content was observed in untreated trees (T12) of Carrizo citrange (24.39 ppm) and Rough lemon (23.90 ppm) rootstock.

Zinc (Zn) content (ppm)

The application of growth regulators have a significant effect on the Zinc content of leaves of Daisy mandarin during the studied years (Fig. 3C). Among the different growth regulators, it was noted that SA 100 ppm (T10) have significantly impact on the nutritional content of leaves followed by other growth regulators. From the given pooled analysis, it was noticed that the highest Zinc content in leaves of both rootstocks i.e. Rough lemon (26.72 ppm) and Carrizo citrange (26.19 ppm) was observed with the foliar application of SA at 100 ppm (T10), followed by other treatments, while lowest was recorded in untreated plants (T12) in Rough lemon (25.91 ppm) and Carrizo citrange (23.64 ppm) (Fig. 3C).

Copper (Cu) content (ppm)

The copper content of leaves of Daisy mandarin was significantly influenced with the application of growth regulators (Fig. 3D). The pooled analysis of the given data indicated that maximum Cu content was recorded in trees treated with SA at 100 ppm (T10) in Carrizo citrange (7.92 ppm) and Rough lemon (7.75 ppm) rootstocks. In contrast, the lower Cu content were observed in untreated plants (T12) of Carrizo citrange (7.58 ppm) and Rough lemon (7.51 ppm) rootstocks, respectively.

Boron (B) content (ppm)

The growth regulators application have significant impact on the boron content of leaves of Daisy mandarin during the studied years (Fig. 3E). Among the different growth regulators, it was noticed that the highest boron content was recorded in Rough lemon (40.72 ppm) and Carrizo citrange (38.49 ppm) with the application of SA at 100 ppm (T10) followed by other growth regulators, whereas the minimum boron content was recorded in untreated plants (T12) of Rough lemon (39.91 ppm) and Carrizo citrange (35.94 ppm) rootstocks, respectively during the both the years.

Carbohydrate content of leaves

The carbohydrates content of leaves of Daisy mandarin was significantly influenced with the application of growth regulators during the growing season (Fig. 3F). The pooled analysis revealed that the maximum carbohydrate content was noticed with SA at 100 ppm (T10) in Rough lemon (12.80 mg/g FW) and Carrizo citrange (12.26 mg/g FW) rootstocks respectively. While the minimum carbohydrate content in leaves of Daisy mandarin was recorded in untreated plants of Rough lemon (10.76 mg/g FW) and Carrizo citrange (9.73 mg/g FW) during the studied years.

C/N ratio

The data related to C/N ratio showed significant variation with the application of foliar application of growth regulators (Fig. 3G). The pooled analysis of the given data indicated that, among the different treatments maximum C/N ratio was recorded with the application of SA at 100 ppm (4.82) in rootstock Rough lemon and Carrizo citrange (4.62) followed by other treatments, while the minimum was recorded in untreated plants of Rough lemon and citrange (4.28 and 4.53), respectively.

Discussion

The foliar application of PGRs, shown promising results in improving the yield and fruit quality attributes, while effectively reducing the incidence of fruit splitting in Daisy mandarin. Fruit splitting was found highest in rootstock Carrizo citrange as compared to Rough lemon rootstock. The higher fruit splitting in Carrizo citrange may be linked to greater soluble solids accumulation, weaker anatomical structure, and stress-induced responses compared to Rough lemon. Environmental factors such as nutrient deficiencies and irregular moisture further exacerbate this susceptibility24,25. Fruit splitting is mainly governed by peel plasticity and resistance, physiological traits that can be modulated by the application of SA. Among the various plant growth regulators, SA at a concentration of 100 ppm was found to be the most effective in reducing the fruit splitting in Daisy mandarin. The role of SA’s efficacy in reducing fruit splitting severity can be linked to multifunctional role in plant physiology. As a naturally occurring phenolic compound, SA functions as a signalling molecule as involved in a range of biochemical and physiological processes. SA is recognized for its role in enhancing the photosynthetic activity, facilitating the uptake of nutrients and translocation within the plant tissue, as well as promoting the biosynthesis of plant pigments-all of which are crucial for the proper fruit development and maintaining of structural integrity26. The antioxidant properties of SA further contribute to the cellular protection by reducing the oxidative stress caused by the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), specifically under abiotic stress conditions such as high temperature27,28.

Additionally, the application of SA improved the assimilation of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorous in leaves of Daisy mandarin plants. The enhanced nitrogen content in the leaves may be due to SA-induced upregulation of nitrate reductase activity, which supports the more efficient nitrogen metabolism29. SA also influences the membrane stability and the root architecture, further enhancing the absorption and transportation of nutrients30,31. This increase in nitrogen availability supports the synthesis of chlorophyll and protein formation, ultimately contributing to the improved plant growth and fruit development32. The observed results are align with the findings in citrus, where SA treatments improved the overall nutrient status under both the optimal stress conditions33,34,35. Our results are similar to the findings in Washington Navel oranges and Balady mandarin36,37.

Furthermore, SA treatments significantly enhanced the uptake and accumulation of phosphorus content in Daisy mandarin leaves. This enhanced in phosphorous content may be attributed due to improved root physiological activity and enhanced the expression of phosphate transporter genes38. These changes may contribute to better ATP production, nucleic acid synthesis and membrane structure, all of which are vital for fruit development39. Similarly, enhancement in phosphorus uptake following SA application have been reported in strawberry40. Similar results were observed by Farhangi-Abriz et al.41that application of SA can enhance the phosphorous content in plant parts by biosynthesis of soluble carbohydrates. Similar results were observed by Abdel-Aziz et al.27, who reported that with the application of SA, nitrogen and phosphorous content in leaves were enhanced in pomegranate.

Potassium is a vital macronutrient, plays an important role in numerous physiological functions such as stomatal regulation, activation of key enzymes, osmoregulation and the translocation of photosynthates. In the present study, an enhanced potassium content was observed in Daisy mandarin leaves with the foliar application of SA. This enhancement can be attributed due to SA’s role in increasing the membrane permeability and the activity of ion transporter, which collectively lead to improved nutrient uptake efficiency42. Furthermore, SA has been reported to positively influence the root growth and function, thereby increasing the nutrient absorption from the rhizosphere40. In citrus and other fruit crops, potassium is important for fruit development, size and overall fruit quality. Higher level of potassium levels in leaves are known to support enhanced carbohydrates synthesis and its effective translocation to developing fruits, ultimately resulting in increased yield and improved fruit attributes43. These results are in agreement with the findings of Elwan and El-Hamahmy44, who observed that foliar application of SA in strawberry significantly enhanced leaf potassium content, contributing to improved productivity and fruit quality.

Similarly, a notable increase in calcium content in Daisy mandarin leaves was recorded with the application of SA. The rise in Ca concentration may be attributed to the role of SA in enhancing the nutrient uptake and translocation. SA facilitates the increased membrane permeability and regulates ion transporters, thereby improving calcium absorption from the soil and its subsequent movement to aerial plant parts45. Calcium plays an essential role in maintaining the cell wall structure, membrane stability and overall plant vigor, all of which are critical for sustaining the fruit quality and mitigating the physiological disorders in citrus46. The present findings aligns with the earlier studies, the enhanced calcium content in leaves with the foliar application of SA in various fruit crops. Shafiee et al.47. found that the increased calcium levels in strawberry plants treated with SA, attributing the improvement to better physiological status and nutrient uptake. Similarly, Ibrahim et al.48 reported to improved nutrient content in pomegranate leaves with the application of SA. Similar results were also observed by Dawood et al.36, Eman et al.37 and Ahmed et al.35 in Washington navel orange. Farhangi-Albriz et al.41 further supported these observations, suggesting that SA may enhance the calcium accumulation through increased biosynthesis of soluble carbohydrates, which can facilitate the nutrient uptake.

The foliar application of growth regulators resulted in a significant increase in magnesium content in leaves of Daisy mandarin could be attributed due to their role in improving plant nutrient uptake, photosynthetic efficiency and physiological processes. SA has been reported to enhance the permeability of plasma membranes, facilitates the uptake of ions and improve the nutrient translocation to different plant parts30. Magnesium being the central part of the chlorophyll molecule, plays a significant role in photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism and its adequate presence in leaves is vital for optimal plant growth and fruit development46. These findings are similar to other reports where foliar application of SA increased magnesium and other nutrient levels in various fruit crops. Kazemi et al.49demonstrated that improved Mg and other nutrient content in strawberry and tomato leaves after SA treatment. Similarly, Sharma and Sharma50 noted increased leaf Mg in guava following foliar sprays of SA. The results are in agreement with the findings of Abdel Aziz et al.27, who suggested that application of SA enhanced the potassium, calcium and magnesium content in leaves of pomegranate.

The increased in Fe content in leaves of Daisy mandarin treated with SA can be attributed due to its beneficial effects of SA on mobilization of nutrient and its uptake efficiency. SA is known to modulate root architecture, which enhances the rhizosphere interactions and stimulate the expression of iron transporter genes, thereby improving the Fe uptake from soil30. Apart from this, SA may reduce oxidative stress and improve the chlorophyll synthesis, both of which are highly dependent on sufficient iron availability51. Iron is a vital micronutrient for plants, playing a critical role in various physiological functions such as chlorophyll biosynthesis, respiration, and photosynthesis. Similar improvements in Fe content with SA have been reported in other fruit crops. For e.g. Kazemi et al.49 and Shafiee et al.47 observed increased Fe uptake and improved leaf mineral content in strawberry and tomato, respectively, with the application of SA.

The foliar application of SA significantly enhanced the manganese (Mn) content in the leaves of Daisy mandarin. This improvement can be attributed due to SA’s role in enhancing the root absorption capacity, increasing membrane permeability and activating the metal transporter proteins30. Manganese plays a crucial role in various physiological and biochemical processes such as activation of enzymes, photosynthesis and antioxidant defense. Notably, SA is known to induce the expression of antioxidant enyzmes like Mn-superoxide dismutase, which requires manganese as a cofactor, thereby increasing its internal demand and translocation within the plant system51. Similar results have been reported in Guava and strawberry, with the foliar application of SA, indicating improved micronutrient status and overall plant health49,50. These findings are similar to Abdel Aziz27, who reported increased leaf concentrations of Fe, Mn and Zn in pomegranate with the application of SA.

Zinc is an essential micronutrient involved in the protein synthesis, auxin metabolism and chlorophyll production. Increase in Zn content in Daisy mandarin leaves with the application of SA can be linked to SA’s influence on the nutrient solubility and availability in the rhizosphere, as well as its ability to modulate the expression of metal transporter genes and stress responsive pathways30. SA also facilitates the efficient translocation of Zn from roots to shoots through improved phloem loading, thereby enhancing its accumulation in the foliage. Similar results have been observed in pomegranate and mango, where the application of SA sprays significantly improved the uptake of Zn and contributed to the enhanced growth and yield52. Copper plays an important role in enzymatic functions, such as synthesis of lignin and formation of chlorophyll in plants. This increased accumulation of Cu in leaves with the application of SA treatment could be due to enhanced uptake of nutrients and improved translocation efficiency facilitated by the SA. SA is known to influence the membrane permeability and activate transporter proteins, potentially leading to a greater availability of Cu and mobility within the plant tissues30,53. Apart from this SA can mitigate the oxidative stress and promote the better nutrient retention in leaves by stabilizing cellular membranes and improving the metabolic activity. These findings are align with the previous studies on citrus and other fruit crops, where the foliar application of SA led to increase the micronutrient concentration in leaves by improving the physiological function and plant health49,50.

Boron is a key micronutrient associated with cell wall synthesis, membrane integrity and reproductive development. The significant increase in B content with the application of SA suggested that the SA facilitate the greater absorption and translocation of boron, possibly by improving the phloem mobility and enhancing the activity of root30. Apart from this SA is known to upregulate the stress-responsive genes and stimulate the root growth, which may further contribute to the nutrient uptake54. These results are similar with the previous findings in citrus and guava, where foliar application of SA improved the B content and contributed to better flowering and fruit setting55,56,57.

The increased in the carbohydrate accumulation in leaves of Daisy mandarin with the application of SA could be attributed due to its influence on the photosynthetic activity, stomatal regulation and enzyme activation, all of which contributed to enhancement in carbon assimilation and metabolic efficiency35,51. SA is known to improve the chlorophyll content and maintain the stability of cell membrane, which further responsible for enhancing the photosynthetic efficiency and the biosynthesis of carbohydrates. These findings are similar to the previous studies where the application of SA resulted in enhanced the carbohydrate content in fruit crops such as strawberry and pomegranate35,47. The increased carbohydrate content in plants also suggests improved physiological status, which can contributed to better growth, stress tolerance and fruit quality.

Conclusions

We hypothesize the application of different concentrations of growth regulators may help to reduce fruit splitting and improve the nutrient content of Daisy mandarin leaves. The findings of this study clearly indicate that the foliar application of growth regulators exert a significant influence on the nutrient dynamics of Daisy mandarin leaves under subtropical climatic conditions. Among the different treatments, SA at 100 ppm significantly reduce the fruit splitting and consistently resulted in the highest accumulation of both macro- and micronutrients, including nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium, calcium, magnesium, iron, manganese, zinc, copper and boron. The superior performance of SA at 100 ppm highlights its potential as an effective and the sustainable foliar intervention for enhancing the nutritional status and by extension, the physiological health and productivity of Daisy mandarin. These results suggest that the use of SA at an optimal concentration can be integrated into nutrient management strategies for citrus orchards in subtropical regions, particularly in the Indian Punjab and comparable agro-climatic zones.

Data availability

The data present in this paper will be made available upon reasonable request by the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- CaCO3 :

-

Calcium carbonate

- Ca:

-

Calcium

- CuSO4 :

-

Copper sulphate

- DAFS:

-

Days after fruit set

- EC:

-

Electrical conductivity

- GA3 :

-

Gibberellic acid

- KCI:

-

Potassium chloride

- K:

-

Potassium

- Zn:

-

Zinc

- Cu:

-

Copper

- N:

-

Nitrogen

- P:

-

Phosphorous

- Mg:

-

Magnesium

- OC:

-

Organic Carbon

- NaOH:

-

Sodium hydroxide

- NAA:

-

Naphthalene acetic acid

- P:

-

Phosphorus

- PGRs:

-

Plant Growth regulators

- SA:

-

Salicylic acid

- RCBD:

-

Randomized Complete Block Design

- Fe:

-

Iron

- Mn:

-

Maganese

- B:

-

Boron

- K:

-

Potassium

References

Kaur, K. Management of fruit splitting in Daisy mandarin. PhD. Dissertation, Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana (2023).

Singh, J. et al. Variation in nutrients during the fruit development of Daisy Tangerine. Indian J. Hortic. 77 (4), 633–639 (2020a).

Kaur, K. et al. Impact of foliar application of growth regulators on fruit splitting, yield and quality of Daisy Mandarin (Citrus reticulata). Indian J. Agric. Sci. 94 (2), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.56093/ijas.v94i2.143183 (2024a).

Anonymous. Area and Production of Horticulture Crops: All India. (2023a).

Anonymous Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana. Package of practices for fruit crops. pp 1–2. (2023).

Kaur, K. et al. Physiological and biochemical characterisation of split and healthy Daisy Mandarin (Citrus reticulata Burm.) fruits. New. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/01140671.2024.2371970 (2024b).

Kaur, K. et al. Influence of exogenously applied growth regulators on mitigating fruit splitting and enhancing yield and quality in Daisy Mandarin in an arid irrigated region of Punjab. Erwerbs-Osbeateau 67, 94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10341-025-01323-9 (2025a).

Bindia et al. Improving fruit quality and yield in Daisy Mandarin cultivar by foliar application of manganese and iron. Intl J. Plant. Soil. Sci. 37 (8), 598–6060 (2025).

Kaur, K. et al. Anatomical features of pericarp and pedicel influencing fruit splitting in Daisy Mandarin. J. Food Meas. Charact. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-024-02859-2 (2024c).

Li, J. et al. Effect of Zn and NAA co-treatment on the occurrence of creasing fruit and the Peel development of ‘Shatangju’mandarin. Sci. Hortic. 201, 230–237 (2016).

Singh, G. et al. Effects of potassium application on vegetative growth, fruiting and nutrients status of Kinnow Mandarin under Indian sub-tropical conditions. J. Plant. Nutri. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2022.2068427 (2022).

Singh, J. et al. Seasonal progression in nutrition density of Mandarin cultivars and their relationship with dry matter accumulation during fruit development period. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant. Anal. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103624.2020.1849262 (2020b).

Amiri, M. E. et al. Golchin. Influence of foliar and ground fertilization on yield, fruit quality, and soil, leaf, and fruit mineral nutrients in Apple. J. Plant. Nutri. 31 (3), 515–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904160801895035 (2008).

Ulrich, A. Physiological bases for assessing the nutritional requirements of plants. Ann. Rev. Plant. Physiol. Plant. Mol. Biol. 3, 207–228 (1952).

Kaur, K. et al. Enhancing Daisy Mandarin performance through foliar nutrient treatment. J. Plant. Nutri. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2024.2415477 (2024d).

Nelson, P. W. & Sommers, L. E. Total carbon, organic carbon and organic matter. In Page, A. L., Miller, R. H. & Keeney, D. R. Methods of soil analysis 539–79. (American Society of Agronomy, 1982).

Puri, A. N. Soils, their physics, and Chemistry (Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1949).

Olsen, R. S. Estimation of available phosphorus in soils by extraction with sodium bicarbonate. Circular No. 939. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture (1954).

Knudsen, D. et al. Lithium, sodium and potassium. Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2. Chemical and Microbiological Properties. In (eds Page, A. L., Miller, R. H. & Keeney, D. R.) 225–246. (American Society of Agronomy, 1982).

Isaac, R. A. & Johnson, W. C. Determination of total nitrogen in plant tissue. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 59, 98–100 (1976).

Chapman, H. D. & Pratt, P. F. Methods of Analysis for Soil Plant and Waters (University of California, Division of Agriculture, 1961).

Jackson, M. L. Methods of Chemical Analysis (Prentice Hall of India (Pvt.) Ltd, 1973).

Berger, K. C. & Truog, E. Boron determination in soils and plants. Ind. Eng. Chem. 11, 540–545 (1939).

Barry, G. H. & Castle, W. S. Soluble solids accumulation in ‘Valencia’ sweet orange as related to rootstock selection and fruit size. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 129 (4), 594–598. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.129.4.0594 (2004).

Clemente, R. M. P. et al. Carrizo Citrange plants do not require the presence of roots to modulate the response to osmotic stress. Sci. World J. (2012).

Kaur, K. et al. Comparative analysis of growth regulators on fruit splitting and quality in Daisy Mandarin grafted on Carrizo Citrange. New. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/01140671.2024.2439591 (2024e).

Abdel, A. et al. Response of manfalouty pomegranate trees to foliar application of Salicylic acid. Assiut J. Agric. Sci. 48, 59–74 (2017).

Sharma et al. The role of Salicylic acid in plants exposed to heavy metals. Molecules 25, 540 (2020).

Fariduddin, Q. et al. Salicylic acid influences net photosynthetic rate, carboxylation efficiency, nitrate reductase activity and seed yield in brassica juncea. Photosynthetica 41 (2), 281–284 (2003).

Hayat, S. et al. Salicylic acid: Plant hormone with versatile functions in plant and human health. J. Plant. Interac. 5 (2), 123–131 (2010a).

Khan, W. et al. Photosynthetic responses of corn and soybean to foliar application of salicylates. J. Plant. Physiol. 160 (5), 485–492 (2003).

Zhao, Y. Auxin biosynthesis and its role in plant development. Ann. Rev. Plant. Biol. 61, 49–64 (2010).

Khodary, S. E. A. Effect of Salicylic acid on the growth, photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism in salt-stressed maize plants. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 6 (1), 5–8 (2004).

El-Tayeb, M. A. Response of barley grains to the interactive effect of salinity and Salicylic acid. Plant. Growth Regul. 45 (3), 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-005-4928-1 (2005).

Ahmed, A. et al. Effect of magnesium, copper and growth regulators on growth, yield and chemical composition of Washington navel orange trees. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 8, 1271–1288 (2017).

Dawood, S. A. et al. How to regulate cropping in Balady Mandarin trees using girdling and GA3. Minufia J. Agric. Res. 26, 834–94 (2001).

Eman, A. et al. GA3 and zinc sprays for improving yield and fruit quality of Washington navel orange trees grown under sandy soil conditions. Res. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 3, 498–503 (2007).

Elwan, M. W. M. & El-Hamahmy, A. M. Improved productivity and quality associated with Salicylic acid application in greenhouse strawberry production. Agric. Biol. J. N. Am. 1 (1), 1–7 (2009).

Taiz, L. & Zeiger, E. Plant Physiology and Development (6th ed.). (Sinauer Associates, 2015).

Shafiee, M. et al. Effect of Salicylic acid on growth, yield, and chemical properties of strawberry. J. Med. Plants Res. 4 (6), 548–553 (2010).

Farhangi-Abriz, S. et al. Growth-promoting bacteria and natural regulators mitigate salt toxicity and improve rapeseed plant performance. Protoplasma 257, 1035–1047 (2020).

Hayat, Q. et al. Effect of exogenous Salicylic acid under changing environment: A review. Environ. Exper Bot. 68 (1), 14–25 (2010b).

Kumar, D. & Tiwari, R. K. Influence of foliar spray of plant growth regulators and micronutrients on flowering, fruiting and yield of guava (Psidium Guajava L). Bioscan 11 (3), 1897–1901 (2016).

Elwan, M. W. M., El-Hamahmy, M. A. M., Elwan, M. W. M., El-Hamahmy, M. & A M. and Improved productivity and quality associated with salicylic acid application in greenhouse pepper. Sci. Hortic. 122, 521–26 (2009).

Hayat, S. et al. Salicylic Acid: A Plant Hormone (Springer, 2010c).

Marschner, H. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants 3rd edn (Academic, 2012).

Shafiee, M. et al. Addition of Salicylic acid to nutrient solution combined with postharvest treatments improves shelf life and quality of strawberry fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 68, 26–34 (2013).

Ibrahim, M. et al. Effect of Salicylic acid and ascorbic acid on growth, yield and chemical constituents of pomegranate. Nat. Sci. 9 (1), 26–34 (2011).

Kazemi, M. et al. Influence of Salicylic acid and calcium chloride on postharvest quality and shelf life of tomato fruit. J. Agric. Sci. 3 (3), 162–170 (2011).

Sharma, R. R. & Sharma, V. P. Influence of pre-harvest application of calcium and Salicylic acid on the post-harvest quality of guava fruit. Sci. Hortic. 167, 71–74 (2014).

Arfan, M. et al. Does exogenous application of Salicylic acid through the rooting medium modulate growth and photosynthetic capacity in two differently adapted spring wheat cultivars under salt stress? J. Plant. Physiol. 164 (6), 685–694 (2007).

Kumar, R. et al. Role of micronutrients in improving crop productivity. Indian J. Fert. 6 (8), 58–62 (2010).

Nazar, R. et al. Salicylic acid alleviates decreases in photosynthesis under salt stress by enhancing nitrogen and sulfur assimilation and antioxidant metabolism differentially in two Mungbean cultivars. J. Plant. Physiol. 168 (8), 807–815 (2011).

Singh, V. et al. Impact of foliar application of micronutrients and plant growth regulators on flowering and fruiting of Mango cv. Dashehari. Indian J. Hortic. 73 (2), 185–189 (2016).

Pathak, R. A. et al. Effect of foliar application of Boron and zinc on yield and quality of guava. Asian J. Hortic. 8 (2), 602–605 (2013).

El-Tantawy, M. M. Behavior of guava trees to some foliar applications. World J. Agric. Sci. 5 (4), 407–414 (2009).

Shaban, A. E. A. et al. Potassium and methionine mitigate the alternate bearing of Balady Mandarin via reducing gibberellins and increasing Salicylic acid and auxins. Sci. Rep. 15, 20141. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04943-z

Acknowledgements

The experiment was conceptualized and designed by Dr. Monika Gupta and supervised by Dr. H S Rattanpal, and Dr. T S Chahal designed and supervised the experiments. Data collection, analysis, and the drafting and writing of the manuscript was carried out by Dr. Komalpreet Kaur. Dr. Komalpreet Kaur performed the experiments; Dr. PPS Gill, Dr. Gurteg Singh and Dr. Dimpy Raina critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for final approval.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support, grants or any kind of specific funding was received during this research or for the publication of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The experiment was conceptualized and designed by Dr. Monika Gupta and supervised by Dr. H S Rattanpal, and Dr. T S Chahal designed and supervised the experiments. Data collection, analysis, and the drafting and writing of the manuscript was carried out by Dr. Komalpreet Kaur. Dr. Komalpreet Kaur performed the experiments; Dr. PPS Gill, Dr. Gurteg Singh and Dr. Dimpy Raina critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for final approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors confirm that all the experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the appropriate institutional committees. Furthermore, all the experiments were conducted in accordance with the relevant institutional guidelines and regulations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaur, K., Gupta, M., Rattanpal, H.S. et al. Role of growth regulators on fruit splitting and nutritional status of Daisy Mandarin in subtropical conditions. Sci Rep 15, 40790 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24540-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24540-4