Abstract

Soils containing diatom microfossils is found in different regions of globally marine environments, and exhibits soil properties defying classical soil mechanics. Although the physical and mechanical properties of such soil have been explored, research on its creep characteristics remains limited, leading the creep deformation mechanism unclear. In this study, an artificial diatomite was prepared using diatom powder, kaolinite, montmorillonite, and illite. Triaxial consolidated undrained shear and creep tests were conducted to explore the hydromechanical and creep properties. The microstructure evolution was observed using laser particle size analyzer, scanning electron microscope, and mercury intrusion porosimeter. Besides, the applicability of the creep component model to diatomite was explored. The results showed that for soils containing diatom powder have a higher coefficient of consolidation (1.0 × 10-5m2/s) which is independent of confining pressure. Its failure under CU tests exhibited a barreling mode and strain-hardening process. As for the creep behavior, all diatomite soils under different stress level only exhibited attenuation creep, i.e., the strain rate decreased with time and creep strain was eventually stable. Based on these primary findings, it indicated that the hydromechanical and creep properties were influenced by the unique diatom structure. The numerous hollow pores in the skeleton resulted in a large coefficient of consolidation of diatomite. Additionally, due to frictional and interlocking effects between diatom particles, the undrained shear strength of diatomite was proportional to the confining pressure, and the creep curves showed attenuation creep. The fractional Maxwell model showed highest applicability to diatomite for this creep type. Meanwhile, microstructural observations indicated that there was no significant particle breakage before and after tests when confining pressure was lower than 500 kPa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diatomite, also known as diatomaceous soils, are characterized by the presence of diatom microfossils. The formation of diatomite is closely related to volcanism1, in which a large amount of dissolved silica and other nutrients are available for the growth and reproduction of diatoms due to volcanoes. The remains of dead diatoms are deposited to the seabed or the bottom of the lakes, followed by a dissolution of organic matter, and eventually their skeletons combining with other deposits are turned to the final sediment. Given the correlation between its formation and volcanic movements, research on diatomite starting from 1970 s has been ongoing in various geologically active regions and plate junctions, such as the marina regions of Mexico2,3, Japan4,5, and Colombia6,7. As reported and observed in current researches, diatomite is typified by its physical and hydromechanical properties defying classical soil mechanics owing to the presence of diatom skeletons.

The current researches on diatomite itself as a special soil have revealed the effect of diatom microfossils on its soil physical properties, hydromechanical properties and creep behaviours. It was determined that as the diatom content rises, the liquid limit, plastic limit, and activity of diatomite increase, whereas the density decreases8,9. The alteration in physical properties can be primarily attributed to the unique structure of diatoms, characterized by high porosity and, consequently, a strong water-absorption capability1,8. This structure also significantly affects the compressibility of diatomite, a topic on which has been extensively studied by one-dimensional consolidation tests1,5,7,9,10,11,12. Diatomite exhibits distinct compression behaviour in comparison to typical natural clayey or silty soils. Specifically, natural diatomite has a larger compression index (Cc) and a smaller swell index (Cs), resulting a greater Cc/Cs ratio (> 30), whereas natural silty or clayey soils has a ratio of 3–713. Moreover, it has been observed that the compression index and swell index increase with the increase of diatom content in artificially prepared diatomite14,15,16. Possible explanations for the distinct compression behaviour are the irreversible fragmentation of diatom particles when the consolidation pressure exceeds a certain value5,15, diatoms individual strength and stiffness17, and types of clay minerals15.

In classical soil mechanics, it is widely recognized that the internal friction angle is inversely proportional to the liquid limit. However, researches on diatomite shows an opposite tendency that both the liquid limit and the internal friction angle increase with the diatom content. In diatomite, the internal friction angle falls in a range of 35–45°, a relatively high value for silty soils1,5,18,19. It is primarily attributed to the chemical component of diatom microfossils (i.e., silica), and their rough surface and consequent interlocking effect when particles come into contact with each other20,21,22,23. Besides, the creep properties of diatomite have also been investigated, showing that the coefficient of secondary consolidation is decreased with the liquid limit while increased with higher diatom content7,14,15.

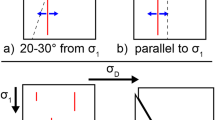

In typical silty or clayey soils, the creep deformation can be divided into two types, namely the attenuation creep and non-attenuation creep24. When the stress is lower than the stress critical value σs, the soils exhibit an attenuation creep deformation characterized by two stages: a decay creep stage where the deformation rate gradually decreases and a steady creep stage where strain rate is maintained. While the non-attenuation creep occurs as the stress level higher than the threshold, which consists of three stages, including a decay stage, a stable stage, and an accelerated stage where creep deformation rate increases rapidly, leading to a failure on short notice. In terms of diatomite, although its physical and mechanical properties have been investigated by previous researchers, there is little study on its creep characteristics, leaving a knowledge gap of its long-term deformation and implication to geotechnical construction on such soils. With a rapid development of offshore engineering such as wind energy and quay, the settlement analysis of these construction on diatomite soils witness a challenge of its creep behavior. More explicitly, up to now the consolidation and creep tests of diatomite were carried out on the one-dimensional oedometer, in which it is impossible to determine if accelerated creep will occur in diatomite. Besides, the clay mineral used in the artificially-prepared diatomite in previous studies was kaolinite8,14,16,25, without considering the influence of montmorillonite and illite.

The aim of this study is to investigate the hydromechanical and creep properties of artificially-prepared diatomite through triaxial tests, with an observation on its microstructural change (especially diatom particle size and pore structure). The specific objectives are as follows:

-

(1)

To explore the hydromechanical and creep behaviours by triaxial consolidated undrained shear and creep tests under different confining pressure and deviatoric stress;

-

(2)

To verify the applicability of the creep component model to diatomite;

-

(3)

To observe the microstructure change (soil particle breakage and pore structure change) as the soil undergoes shear and creep processes.

Methodology

Materials

Clay minerals and diatom microfossils are present in natural diatomite distributed globally, with a typical constitution of 15 ~ 30% clay and 50 ~ 90% diatoms respectively5,7,12,26,27. Therefore, the diatomite soil used in this study was prepared by mixing clay minerals and diatom powders in a ratio of 7:3, which followed a similar ratio in artificial diatomite utilized in previous studies14,16,25. Noticing in these researches kaolinite was regarded as the predominant or even the only clay mineral. However, diatomite typically contains an amount of montmorillonite and illite2,28,29. In order to mimic the properties of natural diatomite, the clay minerals used in this study consisted of a mixture of kaolinite, montmorillonite, and illite in a ratio of 2:1:1 as observed by previous investigations28,29.

The diatom powders used in this study were Cainozoic deposit of diatomite mine in Changbai County, Jilin Province, China, and the kaolinite (Sigma-Aldrich, Guangzhou Fargo Bio-Minerals Co., USA), montmorillonite (Acmec, Shanghai Jizhi Biochemical Technology Co., China), and illite (Dingsheng Chemical Glass, Guangzhou Dingsheng Chemical Glass Instrument Co., China) were commercial products, as shown in Fig. 1. The specific gravity of diatom powder, kaolinite, montmorillonite, and illite are 2.01, 2.6, 2.5, and 2.7, respectively. The microscopic images of diatom powder at different magnifications (Fig. 1b) show that the diatom powder contained a number of disc-shaped diatom skeletons, each possessing numerous hollow pores on its surface. The pore diameter in the edge area of the skeletons was about 1 μm while in the center it was smaller. This porous structure of diatom microfossils could contribute to the low specific gravity of diatomite soil particles5,11,12,30. And it can also be observed from Fig. 1b that the pure kaolinite, montmorillonite, and illite consist of many aggregates.

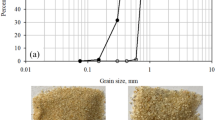

The chemical composition and particle size distribution of diatom powder and clay minerals are illustrated in Fig. 2. The result of XRD analysis revealed that the diatom powder mainly consisted of quartz and opal, which was consistent with the analysis in other literatures16,29. Figure 2b illustrated the particle size distribution of the diatomite used in this study by a comparison to representative diatomite from Chile12, Colombia11, Japan28, China16, and Mexico26. The diatoms used in this study were the range of silt and for most of natural diatomite, the soils were clayey to silty.

The triaxial consolidated undrained shear test

In order to determine the undrained shear strength of diatomite under different confining pressures, triaxial consolidated undrained shear tests (CU) were carried out in this study, with the confining pressures of 100, 200, 300, and 500 kPa, respectively. It should be noted that the maximum confining pressure in this study was 500 kPa, which corresponds to stress levels relevant to offshore engineering foundations at depths of about 5–30 m. While this range is representative of practical engineering conditions, it is lower than the stress levels (2 ~ 6 MPa) reported in previous studies to induce extensive diatom skeleton breakage (Zhang et al.16). Prior to the experiment, kaolinite, montmorillonite, illite, and diatom powder were oven dried at 105 °C and then mixed according to the corresponding ratios. The distilled water was subsequently added to the diatomite to a soil moisture content of 70%. After the mixing, diatomite soil samples were sealed with a cling film to prevent water loss, and then cured at room temperature for 24 h for a homogeneous moisture distribution. The moisture content of the diatomite was measured again after 24-hour curing. A triaxial sample was then prepared by moisture tamping method at a desired dry density (0.66 g/cm3), the reason for using such a small value is because the pore ratio of natural diatomite is very large, and some natural pore ratios even exceed 57,9. The physical parameters of triaxial specimen are shown in Table 1. The prepared specimens underwent vacuum saturation and back pressure saturation until the B value exceeded 0.95, followed by a consolidation at the desired confining pressure and shear at a shear rate of 0.08 mm/min. The undrained shearing process was complete until the axial displacement reached 20 mm.

The triaxial consolidated undrained creep test

In this study a total of 8 groups of undrained creep tests were carried out by controlling the two variables of confining pressure and deviatoric stress separately, and a scheme of creep test is listed in Table 2. The apparatus and specimens of the creep tests were the same as those of the triaxial consolidated undrained shear tests. The CU test employed strain control, while stress control was utilized in the creep process. The corresponding axial force was applied for creep after the completion of consolidation. The creep test was deemed to be completed when the creep deformation rate was less than 0.05 mm/d, or the time of the stable creep stage reached 7 days, or the accelerated creep occurred and the specimen failed (deformation larger than 20 mm).

Microstructure observations

Existing researches have shown that diatomite undergoes particle breakage under stress5,14,27, mainly referring to the fracture of diatom skeletons, which can lead to significant changes in the microstructure of the soil, particularly in the shape, size, and pore structure of the particles. In order to explore the deformation mechanism of diatomite at a micro scale, laser particle size analyzer, scanning electron microscope (SEM) and mercury intrusion test (MIP) were used to observe microstructural change before and after test in this study. The model of the laser particle size analyzer was UK Marvin Mastersizer 2000, offering a testing range from 0.1 μm to 1000 μm, with anhydrous ethanol as the dispersant to soil samples. Scanning electron microscope was conducted by Tescan Mira4, with an acceleration voltage of 5 kV. Mercury intrusion test was carried out by a mercury porosimeter (AutoPore IV 9500, MicroActive, US). Before conducting electron microscopy scanning and mercury intrusion test, the soil samples were frozen using liquid nitrogen (− 196 ℃) and then dried in vacuum for 24 h to prevent structural changes.

Results and discussions

Consolidation behaviours

Consolidation leads to a decrease in void ratio of diatomite, and the greater the consolidation pressure, the greater the reduction in void ratio. Figure 3a shows the dissipation curves of excess pore water pressure during the triaxial consolidation stage, revealing that the excess pore water pressure in diatomite dissipated significantly within 0.3 h, which indicated a relatively large coefficient of consolidation Cv for diatomite. The coefficient of consolidation under different consolidation pressures was obtained using the time square root method as shown in Fig. 3b. It was observed that the coefficient of consolidation of diatomite remained relatively constant with the rise in consolidation pressure, primarily falling within the range of 1 ~ 2 × 10−5 m²/s. This measured value surpassed the result of Zhang et al.16, which was obtained from one-dimensional consolidation tests by more than 10 times and exceeded the coefficient of consolidation of typical silty clay (approximately 10−8 m²/s) by more than 100 times. Although the diatom powders used by Zhang et al.16 are similar to those used in this study, the difference in Cv is attributed to different test method and clay minerals. The significant coefficient of consolidation of diatomite, comparing to those of silty clay, is primarily attributed to the presence of diatom particles within the material: the distinctive structure of diatom particles not only augments the number of inter-particle pores but also enhances the intra-particle pores, creating additional pathways for infiltration14.

Shear behaviours

Figure 4a exhibits the test results of undrained shear strength, where q = σ1 − σ3 is the deviatoric stress and εa is the axial strain. Since the diatomite exhibited strain hardening throughout the shear process without obvious peak strength, the deviatoric stress at 15% axial strain was taken as the undrained shear strength. The testing results are similar to that observed by Caicedo et al.9 but differ from those reported in the literature6,10,27, and this difference is mainly attributed to the difference in dry density, overconsolidation ratio, and shear rate. Besides, a transitional confining pressure in diatomite has been observed by Ovalle et al.27 and Hong et al.5. If the confining pressure falls below the threshold stress, the undrained shear strength remains unaffected by it. However, when the confining pressure surpasses this stress threshold, the undrained shear strength becomes proportional to the increased confining pressure. The relationship between the undrained shear strength and the confining pressure tested in this study was shown in Fig. 4b, which indicated that there was no transitional stress, and the undrained shear strength was always positively correlated with the confining pressure. The transitional stress may be attributed to the cementation of undisturbed soil, and remolded soil will eliminate this cementation.

According to the classical soil mechanics theory, the drainage conditions are artificially controlled for undrained shear tests to prevent the volume of the specimen from changing. During the shear process, the volume change potential is manifested as change in excess pore water pressure. Positive excess pore water pressure is generated in the soil when there is a contraction trend and negative excess pore water pressure is produced in the soil when there is a dilatancy trend. The relationship curve between excess pore water pressure and strain during the shear process for diatomite was shown in Fig. 4c. At first, the pore pressure increased continuously, but as the strain reached a certain value, the pore pressure started to slightly decrease. As a result, during the shear process, the diatomite firstly displayed shear contraction and then showed a slight shear dilatancy. This pattern agreed with the effective stress path result (Fig. 4d), where p’=(σ1’+2σ3’)/3 is the mean effective stress (p’).

The deviatoric stress and excess pore water pressure reached a stabilization when the axial strain reached 22%, therefore it could be considered that the soil had reached a critical state at this point. The stress states at these critical points were graphed in the p’-q plane and linearly fitted according to the equation of critical state curve, q = Mp’. The result was shown in Fig. 4d, in which the critical state parameter M was 1.456 for diatomite. The barreling mode of geotechnical materials after shearing at confining pressures of 100 kPa and 500 kPa is shown in Fig. 4e. Even if the axial deformation was large, there was no obvious shear band observed in the specimen, which contrasts with the findings of Gao et al.10 and Ovalle et al.27. This phenomenon could confirm the barreling mode was influenced by the initial void ratio of sample for diatomite, as the dry density in other studies are different from that in this study.

Creep behaviours

The creep behaviour of diatomite under different confining pressures and deviatoric stresses can be obtained by triaxial consolidated undrained creep tests. The effective stress path curves using stress control during creep process were shown in Fig. 5. Firstly, the deviatoric stress and pore water pressure increased, the mean effective stress decreased. Secondly, the pore water pressure did not reach maximum when the deviatoric stress reached target value, the effective stress path was a horizontal line. Finally, the effective stress path moved horizontally around a point when the pore water pressure reached a relatively stable state.

The strain versus time and axial strain rate versus time curves of diatomite under confining pressures of 100 kPa and 500 kPa are displayed in Fig. 6a–d. Based on the analysis presented in Sect. 1, all test groups of diatomite only exhibited attenuation creep, wherein the strain rate gradually decreased to a stable value or zero with the increase of time, and the overall deformation showed obvious nonlinear characteristics. The deformation of attenuation creep can be divided into two parts: transient elastic-plastic strain ε0 and creep strain εc. The transient elastic-plastic strain is mainly formed by the increase of the deviatoric stress from zero to the target value. Figure 7a shows the transient elastic-plastic strain changing with the stress. It was obvious that the transient elastic-plastic strain increased with the rising deviatoric stress. This behaviour is attributed to the transient elastic-plastic deformation mainly consists of the elastic deformation of the soil particles and plastic deformation due to the redistribution of the position between the soil particles31. Consequently, greater stress results in increased deformation in both aspects. On the other hand, the creep strain refers to the deformation generated during the creep process, mainly caused by the redistribution of soil particles24. It can be derived by subtracting the transient elastic-plastic strain from the total strain. The change trend of creep strain with stress is shown in Fig. 7b, revealing a positive correlation between creep strain and the level of deviatoric stress.

Creep components model

The component model is one of the common constitutive models to describe the creep process of geotechnical materials due to its simplicity. The conventional component model consists of three fundamental components: the Hooke elastic body, Newton viscous body, and Saint Venant plastic body. The Hooke elastic body is represented by a spring to represent transient elastic-plastic deformation, the Newton viscous body is symbolized by a dashpot to represent viscous deformation, and the Saint Venant plastic body is illustrated by a slider, usually in parallel with the Newton viscous body to signify plastic deformation. The effectiveness of fractional calculus in describing the viscoelastic deformation of geotechnical materials has been investigated and demonstrated32. Therefore, fractional calculus has been applied to component models, resulting in a new type of component: fractional dashpot, which not only simplifies the model but also improves its accuracy. There are a number of component models that can describe attenuation creep, with three models standing out for their few parameters and high accuracy: the Merchant model, Burgers model and Fractional Maxwell model. The Merchant model comprises a Hooke elastic body in parallel with a Newton viscous body, connected in series with another Hooke elastic body, featuring three parameters which can be written as follows:

where ε is the strain, σ is the stress, t is the creep time, E is the elastic modulus of the spring component, η is the coefficient of viscosity of dashpot component.

The Burgers model comprised a Merchant model connected in series with a Newton viscous body and has four parameters:

where two viscosity coefficients are applied to describe the creep rate with time.

As for the traditional Maxwell model containing a Hooke elastic body and a Newton viscous body, it can be written as:

where \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{e}\left(t\right)\) is the elastic strain corresponding to the stress change with time, \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{v}\left(t\right)\) is the viscosity strain. Equation (3) can be rewritten as:

or

Based on the fractional theory, the derivative of strain to time can be simplified as a fractional order, the constitutive equation of the Fractional Maxwell model can be expressed as:

where β is a fractional order operator. For triaxial creep tests, σ is the creep deviatoric stress and ε is the axial strain. The schematic diagrams of each model are shown in Fig. 8.

The fitting parameters of each model based on the Least Squares method are shown in Tables 3, 4 and 5; Fig. 9. The fitting results indicated that all three models could describe the creep curve of diatomite to some extent, but the fitting coefficients R2 showed that the fitting accuracy of the Burgers model and the Fractional Maxwell model were better than that of the Merchant model, as the fitting coefficients of the Merchant model were between 0.775 and 0.873, the Burgers model was between 0.939 and 0.976, and the Fractional Maxwell model was between 0.935 and 0.982. The fitting coefficients of the former were significantly smaller than those of the latter two models. Apart from that, it could also be found in Fig. 9 that the Merchant model accurately captured transient elastic-plastic deformation but lacked accuracy in describing deformation during the decay creep stage. It effectively characterized deformation in the stable creep stage at low deviatoric stress, yet its precision diminished at high deviatoric stress. The Burgers model adeptly described transient elastic-plastic deformation and creep deformation at low deviator stress but faltered in accurately representing deformation during the decay creep stage at high deviator stress. Compared to the Merchant model, the Fractional Maxwell model had better consistency with experimental data. Compared to the Burgers model, the Fractional Maxwell model not only had better fitting coefficients but also had one fewer parameter. Therefore, the Fractional Maxwell model had better application potential for diatomite.

The fitting results of the Fractional Maxwell model were very consistent with experimental data. This model could not only reflect the transient elastic-plastic deformation after loading, but also described the deformation of the entire creep process of diatomite. Furthermore, its various parameters were influenced by both confining pressure and deviatoric stress. Specifically, the initial elastic modulus E0 increased with rising confining pressure and decreased with increasing deviator stress, reflecting that the instantaneous elastic-plastic deformation increased with the increase of deviator stress, which was consistent with the test data. The magnitude of the viscosity coefficient ηβ was directly affected by β and exhibited a positive correlation with β. It could be observed that fractional order operator β was inversely proportional to deviatoric stress, while Fig. 7b indicates that creep deformation was proportional to deviatoric stress. Consequently, the viscosity coefficient ηβ was inversely proportional to creep deformation, implying that a smaller viscosity coefficient corresponded to greater creep deformation. It is worth noting that the viscosity coefficient is influenced by multiple factors. Sun33 proposes that the viscosity coefficient is a nonlinear function of stress level, stress state, and creep time. Yin et al.24 finds that there is a negative correlation between creep strain and viscosity coefficient, and β significantly affects the slope of the curves during the decay creep stage and the stable creep stage, as revealed through parameter sensitivity analysis.

Although the component model is also applicable to diatomite, laboratory creep experiments are conducted within a limited time frame, representing short-term deformation. In contrast, the deformation time involved in actual engineering often lasts for decades or hundreds of years, which belongs to long-term deformation. Currently, the long-term deformation characteristics of diatom particles in diatomite remain unknown. Consequently, further researches are in needed to explore how component models can be effectively employed to predict the long-term deformation behaviour of diatomite.

Diatom microstructure change during creep

Prior researches have revealed that diatom particles break when the confining pressure exceeds a certain stress level. Therefore, it is necessary to further observe the microstructural changes of diatomite before and after the test, and seek to uncover potential connections between these changes and macroscopic mechanical properties. Samples under different conditions were selected for scanning electron microscopy observation, which were untested, after shear under confining pressure of 100 and 500 kPa, and after creep under confining pressure of 100 kPa and deviator stress of 0.95σf. The changes in the particles and porosity of the diatomite before and after the test were analyzed by combining the laser particle sizer and mercury intrusion test.

Due to the low viscosity of diatomite with high diatom content, the sample after freeze-drying was accompanied by the detachment of powder particles of soil. To prevent contamination of the scanning electron microscope, the electron microscope sample must be prepared in powder form. The electron microscope scanning results of the four samples are shown in Fig. 10. The particles in diatomite before and after the test could be divided into four categories: diatom frustule, crushed diatom, diatom-clay aggregate and clay aggregate. From the electron microscope results, it could be seen that these four types of particles all existed before and after the test. Since the crushed diatom all existed (Fig. 10a-d) before and after test, and the most of diatoms after test were intact (Fig. 10c-d), the diatomite did not undergo particle breakage. It is noteworthy that the stress applied during particle breakage in other studies exceeds 500 kPa, and in some cases, it even reaches 6 ~ 7 MPa5,12. Therefore, further investigation is required to determine whether the diatomite used in this study undergoes particle breakage under higher pressure.

Compared to scanning electron microscopy, laser particle size analysis can quantitatively analyze the size of soil particles, as shown in Fig. 11a. Because the anhydrous ethanol was used as a dispersant in the laser particle size analyzer analysis, most of the aggregates will be dispersed into single diatom and clay particle during the test. Therefore, the horizontal coordinate of the curve corresponds to the diameter of single diatom and clay particle. From Fig. 11a, it could be observed that the particle size distribution curves all has three peaks. The first peak fell within the range of 25–35 μm, the second peak between 5 and 8 μm, and the third peak between 0.6 and 0.9 μm, which indicated that the highest number of particles fell within these three size intervals in diatomite. The diameters of different particles were labelled in Fig. 10e-f, it can be seen that the diatom particles’ diameters were distributed over a wide range, ranging from 5 to 40 μm. The diatom-clay aggregates typically possessed diameters exceeding 20 μm, while clay aggregates usually fell between 5 and 10 μm. In addition, there was no significant change in the particle size distribution curve, so it could be inferred that the diatom did not undergo significant particle breakage during the experimental process.

Pore characteristic is also an important parameter of soil structure. Tanaka et al.28 classifies the pore system in diatomite into four categories: intra-skeletal pore, skeletal pore, intra-aggregate pore and inter-aggregate pore. The latter three types of pores could be seen in Fig. 10, but no intra-skeletal pore had been found. The structure of intra-skeletal pore is clearly shown in that reference16, and these rich pore structures also confirm the experimental results of diatomite with a coefficient of consolidation far higher than that of ordinary clay. In this study, the pore structure characteristic of diatomite before and after the test were quantified by mercury intrusion test, and the results are presented in Fig. 11b. The pore distribution curve could also be divided into three peaks, the first one was not obvious, corresponding to a pore diameter in the range of 0.2–0.4 μm. The second peak corresponded to the pore diameter in the range of 0.6–1.1 μm, and the third one corresponded to the diameter in the range of 5–6 μm. Previous electron microscopy analysis revealed that the pore diameter in the center of the diatom skeleton was less than 1 μm, the diameter of the pore at the edge was around 1 μm. Therefore, the first peak corresponded to the skeletal pore, while the pore corresponding to the second and third peaks should be aggregate pores. The first peak exhibited almost no change before and after the test, supporting the conclusion that diatoms did not undergo significant particle breakage. The second and third peaks displayed noticeable changes but lacked a clear pattern, such alterations were likely induced by the fragmentation and redistribution of the diatom-clay aggregate. As shown in Fig. 10b, the diatom-clay aggregate had a loose structure. When subjected to pressure, it is possible to either deform or force the surrounding individual diatom or clay particles to adhere to the aggregate, forming a larger particle and more complex aggregate structure.The observed attenuation creep without accelerated failure has direct implications for offshore foundation design and slope stability in diatom-rich deposits. The absence of significant diatom breakage under moderate confining pressures (≤ 500 kPa) suggests that settlements in this stress range may be predictable using constitutive models calibrated to attenuation creep. The successful application of the Fractional Maxwell model further provides a tool for predicting time-dependent deformations in engineering analyses, though long-term parameter stability requires further study.

Conclusions

The consolidation, shear and creep properties of diatomite containing diatom microfossils and clay minerals were investigated by triaxial test and microscopic observation, and the main conclusions are as follows.

-

(1)

The abundant skeletal pore in diatomite provides more channels for seepage, which resulted in a fast excess pore pressure dissipation in the consolidation stage. The coefficient of consolidation of diatomite is more than 100 times of that of ordinary silty clay.

-

(2)

During the shear process, diatomite firstly exhibits shear contraction, followed by a small magnitude of shear dilatancy. The stress-strain curve shows strain hardening.

-

(3)

Due to the interlocking effect between diatom particles, diatomite is relatively less prone to accelerated creep. The creep curve only shows attenuation creep, the deformation rate with the growth of time gradually decreases to a stable value. In view of such creep deformation characteristics, compared with Merchant model and Burgers model, Fractional Maxwell model has the advantages of fewer parameters and higher fitting accuracy, which has a potential to be applied in describing the creep deformation of diatomite.

-

(4)

The PSD curve and the pore distribution curve of diatomite are both triple-peaked. When the confining pressure is lower than 500 kPa, there is no obvious particle breakage of diatom after the shear or creep test, and the changes in particle size and pore structure are likely to be caused by aggregate fragmentation and redistribution.

These findings contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the mechanical and deformational behaviour of diatomite, shedding light on its unique characteristics and potential applications in geotechnical engineering. It should be emphasized that the creep tests in this study were limited to durations of days to weeks, which reflects short-term deformation behavior. In engineering practice, however, foundations and slopes in diatomaceous soils may experience creep over decades. While the Fractional Maxwell model provided an excellent fit to the laboratory data and effectively described attenuation creep, the validity of its parameters for long-term predictions remains uncertain.

The development of strain and strain rate with time during the creep test (a) Strain versus time curves under σ3 = 100 kPa; (b) Strain rate versus time curves under σ3 = 100 kPa; (c) Strain versus time curves under σ3 = 500 kPa; (d) Strain rate versus time curves under σ3 = 500 kPa. Both of strain and strain rates increase with higher stress level.

Creep test data and the component models’ fitting results under different confining pressure (a) σ3 = 100 kPa; (b) σ3 = 200 kPa; (c) σ3 = 300 kPa; (d) σ3 = 500 kPa. All models provide a reasonable prediction of creep development, among which Fractional Maxwell model shows the highest precision with fewer parameters.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Cc :

-

Compression index

- Cs :

-

Swell index

- σs :

-

Stress critical value

- CU:

-

Triaxial consolidated undrained shear test

- σ1 :

-

Axial stress

- σ3 :

-

Confining pressure

- σf :

-

Undrained shear strength

- q:

-

Deviatoric stress

- Cv :

-

Coefficient of consolidation

- εa :

-

Axial strain

- p':

-

Mean effective stress

- M:

-

Critical state parameter

- Δu:

-

Excess pore water pressure

- ε0 :

-

Transient elastic—plastic strain

- εc :

-

Creep strain

- E:

-

Elastic modulus

- η:

-

Coefficient of viscosity

- β:

-

Fractional order operator

References

Shiwakoti, D. R., Tanaka, H., Tanaka, M. & Locat, J. Influences of diatom microfossils on engineering properties of soils. Soils Found. 42, 1–17 (2002).

Mesri, G., Rokhsar, A. & Bohor, B. F. Composition and compressibility of typical samples of Mexico City clay. Géotechnique 25, 527–554 (1975).

Díaz-Rodríguez, J. A., Cruz, R. L., Dávila-Alcocer, V. M., Vallejo, E. & Girón, P. Physical, chemical, and mineralogical properties of Mexico City sediments: a geotechnical perspective. Can. Geotech. J. 35, 600–610 (1998).

Holler, P. R. et al. Consolidation characteristics and permeabilities of sediments from the Japan sea (sites 798 and 799). Proc. ODP Sci. Results. 127-128, 1123–1133 (1992).

Hong, Z., Tateishi, Y. & Han, J. Experimental study of macro- and microbehavior of natural diatomite. J. Geotech. Geoenviron Eng. 132, 603–610 (2006).

Caicedo, B., Mendoza, C., Lizcano, A. & Lopez-Caballero, F. Some contributions to mechanical behaviors of lacustrine deposit in bogotá, Colombia. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 11, 837–849 (2019).

Mendoza, C., Caicedo, B. & Duque, J. Technical report on the compression, structure, and creep behaviors of lacustrine soil deposits in bogotá, Colombia. Soils Found. 62, 101215 (2022).

Xu, Y., Zhang, X., Liu, X. & Wang, G. Alterations of physical properties and microstructure of marine diatomite owing to variation of diatom content. Mar. Geores Geotechnol. 41, 376–387 (2023).

Caicedo, B., Mendoza, C., López, F. & Lizcano, A. Behavior of diatomaceous soil in lacustrine deposits of bogotá, Colombia. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 10, 367–379 (2018).

Gao, L., Luo, Y., Kang, Y., Gao, M. & Abdulhafidh, O. Experimental study on physical mechanical properties and microstructure of diatomite soil in Zhejiang province, China. Appl. Sci. 12, 387 (2022).

Caicedo, B., Zuluaga, D. & Slebi, C. Effects of micro-features of fossil diatom on the macroscopic behaviour of soils. Géotechnique Lett. 9, 322–327 (2019).

Arenaldi Perisic, G., Ovalle, C. & Barrios, A. Compressibility and creep of a diatomaceous soil. Eng. Geol. 258, 105145 (2019).

Bardet, J. P. & Hall, P. Experimental soil mechanics. Experimental Soil. Mech. 57, 2973–2980 (1997).

Sonyok, D. R. & Bandini, P. Oedometric behavior of diatomite–kaolin mixtures. J. Geotech. Geoenviron Eng. 145, 6019005 (2019).

Wiemer, G., Dziadek, R. & Kopf, A. The enigmatic consolidation of diatomaceous sediment. Mar. Geol. 385, 173–184 (2017).

Zhang, X., Liu, X., Xu, Y., Wang, G. & Ren, Y. Compressibility, permeability and microstructure of fine-grained soils containing diatom microfossils. Géotechnique. 1–15 (2023).

Hamm, C. E. et al. Architecture and material properties of diatom shells provide effective mechanical protection. Nature 421, 841–843 (2003).

Cheng, X. H., Ngan-Tillard, D. & Haan, E. J. D. The causes of the high friction angle of Dutch organic soils. Eng. Geol. 93, 31–44 (2007).

Díaz-Rodríguez, J. A. Characterisation and Engineering Properties of Mexico City Lacustrine Soils (Characterization and Engineering Properties of Natural Soils, 2003).

Wang, J., Yazdani, E. & Evans, T. M. Case study of a driven pile foundation in diatomaceous soil; I, site characterization and engineering properties. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 13, 431–445 (2021).

Day, R. W. Engineering properties of diatomaceous fill. J. Geotech. Eng. 121, 908–910 (1995).

Polidori, E. Relationship between the Atterberg limits and clay content. Soils Found. 47, 887–896 (2007).

Sollecito, F. et al. Effects of bio-chemo-mechanical processes on the properties of contaminated marine sediments. Géotechnique 73, 506–520 (2023).

Yin, Q. et al. A fractal order creep-damage constitutive model of silty clay. Acta Geotech (2023).

Xu, Y., Zhang, X., Wang, G., Liu, X. & Yan, L. Effects of diatom content on rheological properties of marine diatomite. Mar Geores Geotechnol ahead-of-print, 1–15 (2023).

Daniel, Z., Ruge, J. C., Camacho-Tauta, J., Reyes-Ortiz, O. & Caicedo-Hormaza, B. Diatomaceous soils and advances in geotechnical engineering—part i. Appl. Sci. 13, 549 (2023).

Ovalle, C. & Arenaldi-Perisic, G. Mechanical behaviour of undisturbed diatomaceous soil. Mar. Geores Geotechnol. 39, 623–630 (2021).

Tanaka, H. & Locat, J. A microstructural investigation of Osaka Bay clay: the impact of microfossils on its mechanical behaviour. Can. Geotech. J. 36, 493–508 (1999).

Yuan, P., He, H. P., Wu, D. Q., Wang, D. Q. & Chen, L. J. Characterization of diatomaceous silica by Raman spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 60, 2941–2945 (2004).

Zhang, Y., Guo, C., Yao, X., Qu, Y. & Zhou, N. Engineering geological characterization of clayey diatomaceous Earth deposits encountered in highway projects in the Tengchong region, yunnan, China. Eng. Geol. 167, 95–104 (2013).

Bai, B., Zhou, R., Cai, G., Hu, W. & Yang, G. Coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical mechanism in view of the soil particle rearrangement of granular thermodynamics. Comput. Geotech. 137, 104272 (2021).

Cai, W., Chen, W. & Xu, W. Characterizing the creep of viscoelastic materials by fractal derivative models. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 87, 58–63 (2016).

Sun, J. Rock rheological mechanics and its advance in engineering applications. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 26, 1081–1106 (2007).

Funding

This work was supported by the CCCC Fourth Harbor Engineering Co., Ltd. (No. 76140-71020071), Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China(Grant No. 42207188) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2023A1515012116).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yue Zhang conducted the experiments, analyzed data and wrote the main manuscript text; Hongjie Lin wrote the manuscript text; Jianyu Li provided the material and conducted the preliminary tests; Ke Chen reviewed the manuscript and provided the model establishement method; Jiankun Liu supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Lin, H., Li, J. et al. An experimental exploration on the creep behaviour of fine-grained soils containing diatoms microfossils and insight into microstructure evolution. Sci Rep 15, 40713 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24575-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24575-7