Abstract

This paper investigates the feasibility of using Korean-produced biochar derived from wood (WB), rice husk (HB), and poultry manure (MB) as a cement replacement in mortar. The physicochemical and microstructural characteristics of each biochar were analyzed, and mortar specimens containing 5% biochar were tested for flow and compressive strength. WB and HB showed favorable particle sizes and large specific surface areas, enhancing internal curing and filler effects, which resulted in up to 29% higher compressive strength than plain mortar at 28 days. In contrast, MB, with coarse particles and low surface area, improved flowability but significantly reduced compressive strength by about 44%. Analytical results confirmed that WB and HB have higher carbon content and chemical stability than MB. These results demonstrate that feedstock type and physicochemical properties affect mortar performance. WB and HB showed potential for use as supplementary cementitious materials based on their strength and workability performance, whereas MB was shown to be unsuitable due to its inferior properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In response to an acceleration in global climate change, major countries around the world have established policies to reduce carbon emissions and are actively pursuing strategies to achieve carbon neutrality. In 2019, the European Union (EU) unveiled the EU Green Deal with the objective of achieving carbon neutrality by 20501. Similarly, the United States declared its intention to attain zero carbon emissions in select industrial sectors by 2035, with a broader goal of achieving total carbon neutrality by 2050. Concurrently, China has set a goal of carbon neutrality by 2060, and Japan and South Korea by 2050, respectively. In addition, the United States is set to introduce the Clean Competition Act, and Europe the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism to strengthen regulations for industries with high carbon intensity2. These policies underscore the necessity for substantial carbon reduction in major industrial sectors, including the construction industry. Key reduction measures in the construction sector include the use of low-carbon building materials, improvements in energy efficiency, and the increased adoption of renewable energy. The cement used in the construction industry is estimated to account for approximately 7% to 8% of global carbon dioxide emissions, highlighting the need for the cement industry to adopt a low-carbon strategy to achieve carbon neutrality. Consequently, there is a growing imperative to develop and introduce low-carbon construction materials that can effectively reduce carbon emissions throughout the production and utilization of cement3.

The cement industry is exploring the use of alternative raw materials that have the potential to reduce carbon emissions and optimize processes to implement carbon capture and storage technology. Of particular interest is the utilization of biomass-based materials as low-carbon construction materials. Of these, biochar, a porous carbon-based material that is produced by pyrolyzing organic waste, has attracted particular attention due to its potential for effective carbon sequestration and sustainable supply4. Biochar has been used as a soil conditioner or adsorbent5 and, more recently, ongoing research has examined its potential use as a cement substitute and admixture in the construction industry and thus as an eco-friendly construction material6,7.

Previous studies have focused on strength characteristics and the impact on the hydration reaction when biochar is incorporated into cement mortar. The physical structure of biochar acts as a filler in the cement matrix and the moisture-retaining properties of biochar can promote strength development in cement mortar. In particular, research has confirmed that the water retention characteristics of biochar can promote internal curing and have a positive impact on the hydration reaction of cement8. In addition, the particle size of biochar is an important factor that affects the physical properties of mortar. Researchers have reported that biochar with fine particles of 0.1 ㎛ to 2 ㎛ exhibits better workability and early strength development than biochar with particles of 2 ㎛ to 100 ㎛9. Even if biochar is substituted for up to 5% of the cement weight, it can be used without reducing the material’s strength within a certain substitution rate. Further, an incorporation level of 1% to 2% biochar can contribute to the cement’s compressive and flexural strength6,10.

Also, the performance characteristics of biochar can vary depending on the pyrolysis temperature of the biochar and the type of biomass feedstock from which it is made. As the pyrolysis temperature of the biochar is increased, the fixed carbon content and specific surface area also increase11,12, and these characteristics act as factors that affect the performance of mortar and concrete13. The high porosity of biochar increases the water absorption rate of mortar and concrete, and this absorption capacity is enhanced further by a large specific surface area14. The particle surface morphology of biochar coupled with the type of biomass feedstock are important factors that affect the flow and compressive strength of mortar15. The feedstock characteristics can lead to different test results, not only in terms of compressive strength but also in mechanical performance characteristics such as flexural strength and tensile strength. In particular, biochar has been shown to reduce the pore size in concrete while improving the connectivity between hydration products, which increases the material’s flexural strength and helps to inhibit early cracking and failure16,17. These results show that not only the chemical properties of biochar but also physical properties such as particle size can affect the performance of cement-based materials. The results also demonstrate that biochar can be used as a building material under appropriate mixing conditions to improve the performance of mortar and concrete while reducing carbon emissions.

However, previous studies have been limited in their capacity to compare and analyze changes in the performance of cement composites according to variables such as the raw materials of the biochar, pyrolysis conditions, and particle size. This limitation is particularly problematic given the recognized fact that the performance of cement composites may vary depending on the raw materials and characteristics of the biochar. For example, the different biochar types produced in Korea and other regions differ in terms of the pyrolysis method applied, raw material characteristics, and particle size, suggesting that discrepancies in their mechanical performance with regard to cement composites may also vary. However, little research is available that has quantitatively compared the physical and chemical properties of various biochar types available in Korea under consistent conditions or has systematically evaluated the effects of these properties on the mechanical performance of cement composites according to KS L 512218. This study aims to provide basic comparative data to identify the biochar suitable for use as an SCM and to support further application at the concrete level.

According to KS L 5122, alternative supplementary cementitious materials (ASCM) are defined as materials that contribute favorably to the strength, durability, workability, and other properties of concrete or mortar. This Korean standard recommends powdered materials that are not included in blast furnace slag, fly ash, or silica fume as corresponding admixtures. For biochar to be used successfully in the construction industry, its applicability must be substantiated through material property analysis and mortar and concrete performance evaluation, as specified in KS L 5122.

In this study, the possibility of using domestically produced wood-based, rice husk-based, and poultry manure-based biochar as cement substitute admixtures was evaluated. These biochars are hereafter referred to as WB, HB, and MB. To this end, the physical and chemical properties of each biochar type were analyzed, and the replacement rate of biochar mixed into the mortar was set according to the cement weight ratio. Then, mechanical performance tests of the mortar specimens were conducted. Based on the test results, differences in performance according to the characteristics of the biochar raw materials were quantitatively analyzed, and the applicability of WB, HB, and MB as cement-based admixtures was evaluated.

Experimental program

Materials

Biochar derived from wood, rice husk, and poultry manure, all produced domestically in Korea, was used in this study. WB was obtained by pyrolyzing wood pellets at 650 °C to 800 °C, HB at 500 °C to 700 °C, and MB at approximately 400 °C. To use the biochar as a cement substitute, all samples were dried at 105 °C for 24 h and subsequently ground for 30 min at 300 rpm using a roll mill. Identical grinding conditions were applied across all three biochar types. Figure 1 shows the appearance of each biochar sample before and after grinding.

Biochar samples before and after grinding using a roll mill: (a) wood-based biochar before grinding, (b) wood-based biochar after grinding, (c) husk-based biochar before grinding, (d) husk-based biochar after grinding, (e) manure-based biochar before grinding, and (f) manure-based biochar after grinding.

Analysis method

Physicochemical analyses were conducted to evaluate the properties of the crushed biochar samples and to assess the suitability of each biochar type as a cementitious composite. These analysis methods included particle size distribution (PSD), scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray (SEM–EDX) spectroscopy, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area analysis, true density analysis, moisture absorption analysis, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis.

PSD analysis was employed to determine the particle size and distribution of the crushed biochar, and the results were compared with the particle size of ordinary cement to evaluate the biochar’s suitability as a cement substitute. SEM and SEM–EDX spectroscopy analyses were performed to determine the microstructure and the composition of the major elements present on the surface of each biochar sample. BET analysis and true density measurements were used to calculate the specific surface area and porosity of the samples and to analyze the water storage capacity of the biochar. Moisture absorption tests were conducted to indirectly ascertain the hydration reaction and its effect on the fluidity of the mortar by evaluating the hygroscopicity of the biochar. TGA was carried out to quantitatively evaluate the residual moisture content based on the mass loss rate in the 100 °C to 200 °C range, along with the thermal stability of the samples. Finally, the crystalline structure of the biochar was confirmed through XRD analysis and compared with the XRD library to identify similar structural characteristics.

Compressive strength tests

Compressive strength tests were conducted using cement mortar specimens containing biochar to evaluate its applicability as a cement replacement admixture. The compressive strength tests were in accordance with ASTM C10919, with a water-to-cement ratio of 0.485 and cement-to-standard sand ratio of 1:2.75. Loading was applied using a universal testing machine with a maximum capacity of 1,000 kN, and the loading rate was controlled within the range of 0.36 MPa/s to 0.72 MPa/s under stress control mode. The replacement rate of biochar was set at 5% by weight of cement, and the mixing procedure specified in ASTM C109 was followed. To ensure consistent test conditions and enable comparison of different types of biochar, a uniform replacement ratio of 5% was applied. Three specimens were prepared for each variable. After casting, the specimens were cured at a controlled temperature in a humidity room for 24 h, then demolded and water-cured at 23 °C ± 2 °C until the designated testing age. the average compressive strength of the three specimens was used. In parallel, flow tests were conducted in accordance with ASTM C143720 to evaluate the workability of the fresh mortar. Table 1 presents the mix proportions based on the cement replacement ratios. In the specimen ID, WB_5%, for example, indicates that wood-based biochar was used to replace 5% of the cement by weight.

Results and discussion

Particle size distribution (PSD)

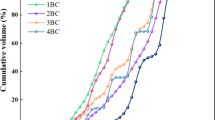

Table 2; Fig. 2 present the results of the PSD analysis. Despite the application of identical roll-milling conditions, noticeable differences in the PSD of the different biochar specimens were observed, which likely originated from structural and physical differences related to the characteristics of the biomass feedstock. Figure 2 (a) and (b) show that the WB and HB exhibited relatively uniform PSD, with more than 60% of the particles distributed in the 10 μm to 50 μm range. The average particle size of the WB was 22.3 μm, which is comparable to that of ordinary Portland cement (typically < 50 μm)6. In contrast, Fig. 2 (c) shows that the MB exhibited the largest average particle size at 65.1 μm, with approximately 30% of the particles exceeding 100 μm. The cumulative PSD shown in Fig. 2 (d) also indicates that the WB and HB have similar curves, whereas the MB exhibited a coarser overall distribution.

Previous studies have reported that materials with a particle size of less than 125 μm can act as fillers even if they are non-pozzolanic and that finer particles are more advantageous in contributing to the filler effect9,21. Therefore, all three types of biochar used in this study are expected to be able to provide filler effects when used as cementitious admixtures.

Scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM, SEM–EDX)

Table 3; Fig. 3 present the SEM and SEM–EDX spectrometry analysis results of the three types of biochar used in this study alongside elemental analysis data from previous studies. Figure 3 (a) shows that the WB exhibits a porous structure, which is derived from the morphology of its cellulose cell walls. Similarly, Fig. 3 (c) shows that the HB also displays a porous structure. In contrast, Fig. 3 (e) shows a relatively low degree of porosity for the MB. According to the EDX spectrometry analysis, the WB and HB exhibited relatively high carbon contents, whereas the MB showed a lower carbon content. When comparing the elemental composition of the biochar types analyzed in this study with those reported in previous studies, the carbon content of this study’s WB is within the range of values previously reported for similar WB. The carbon content of the HB is higher than that of rice husk, husk, and rice waste biochar reported in the literature. These findings suggest that, even within the same biochar category, variations in feedstock type, pyrolysis temperature, and processing method can result in differences in the residual carbon content. Although the MB used in this study exhibited a higher carbon content than other manure-derived biochar, such as chicken manure biochar (CMB), poultry litter biochar (PLB), and raw poultry litter (PL) used in previous studies, the MB carbon content was still lower than that of the WB and HB. This outcome is likely due to the presence of various inorganic components in the manure feedstock compared to other biomass sources23.

When comparing the oxygen-to-carbon (O/C) ratios, the WB and HB exhibited values of 0.13 and 0.17, respectively, while the MB showed the highest value of 0.5. Previous studies also have reported that the O/C ratio of WB is lower than that of HB and MB. Further, research has shown that biochar with an O/C ratio below 0.2 demonstrates the highest level of chemical stability24. Therefore, the WB and HB used in this study are expected to possess high levels of chemical stability, making them suitable for long-term carbon storage and utilization. In contrast, the MB, with its relatively high oxygen content and low carbon content, is considered to have lower chemical stability compared to the other two types.

SEM and SEM-EDX spectrometry analysis results of each biochar sample: (a) SEM image of wood-based biochar, (b) EDX spectrum of wood-based biochar, (c) SEM image of husk-based biochar, (d) EDX spectrum of husk-based biochar, (e) SEM image of manure-based biochar, and (f) EDX spectrum of manure-based biochar.

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) and true density analysis

Table 4; Fig. 4 present the BET and true density analysis results alongside data from previous studies. According to the BET analysis, the HB has the largest specific surface area and the smallest average pore diameter. The WB also shows a relatively large surface area and small pore diameter. In contrast, the MB exhibits the smallest specific surface area among the three biochar types and the largest average pore diameter, measured at 11.9 nm. Figure 2 (c) shows that more than 30% of the MB particles exceeded 100 μm in size, and Fig. 3 (e) confirms that the MB’s porous structure is less developed compared to that of the other two biochar types. These structural differences are the likely contributors to the smaller surface area and larger pore diameter observed for the MB compared to the other two biochar types.

Biochar tends to have a larger specific surface area and more developed porous structure with an increase in the pyrolysis temperature23. For example, the MB pyrolyzed at 600 °C shows a larger specific surface area and greater pore volume compared to the MB produced at 300 °C, while exhibiting a decrease in mean pore diameter22. The MB analyzed in this study was produced at approximately 400 °C. When compared to the characteristics of CMB 300 (pyrolyzed at 300 °C) and CMB 600 (pyrolyzed at 600 °C) used in previous studies22, the specific surface area and pore diameter of this study’s MB are within the range of these two reference samples. These results indicate that specific surface area and pore structure formation in biochar are properties that are influenced by the pyrolysis temperature, which also suggests that optimizing the pyrolysis temperature can enhance the beneficial properties of biochar for various applications, such as soil amendment and carbon sequestration. Further research is needed to explore ways that these characteristics affect the biochar’s performance in different environmental contexts.

Earlier research has shown that biochar with a large specific surface area and high porosity tends to exhibit a high water absorption capacity14. Based on these characteristics, MB, which has a relatively small specific surface area and large pore diameter, is expected to exhibit less water absorption capacity when mixed into cement. In contrast, WB and HB, characterized by larger specific surface areas and smaller pore diameters, are anticipated to show superior water absorption performance compared to MB. In terms of true density, the HB in this study exhibited the highest value among the three samples. All three biochar types showed lower true density values than that of ordinary Portland cement (3.15 g/cm³), indicating that their use as partial cement replacements may result in a reduction in the unit mass of the cementitious composite.

BET analysis results: (a) isotherm linear plot of wood-based biochar, (b) pore volume plot of wood-based biochar, (c) isotherm linear plot of husk-based biochar, (d) pore volume plot of husk-based biochar, (e) isotherm linear plot of manure-based biochar, and (f) pore volume plot of manure-based biochar.

Moisture absorption and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

Figure 5 (a) shows the results of the moisture absorption tests. All the biochar samples were dried completely in a vacuum oven at 100 °C for 24 h prior to testing, and their moisture absorption characteristics were evaluated over a 7-day period under conditions of 100% relative humidity. All samples exhibited a sharp increase in moisture absorption on the first day of testing, followed by a continued, albeit more gradual, increase throughout the remainder of the test period. The HB exhibited the lowest level of overall moisture absorption during the test period, showing minimal change in absorption from day 1 to day 7. In contrast, the MB showed a continuous increase in moisture absorption from the beginning to the end of the test. The WB demonstrated intermediate moisture absorption characteristics. These results indicate that the moisture absorption behavior of biochar varies depending on the properties of the original biomass feedstock.

Figure 5 (b) presents the TGA results, where the thermal stability of each biochar is compared based on the change in residual mass with an increase in temperature. All samples show an initial mass loss of less than 5% up to approximately 150 °C, which is attributed to the desorption of the adsorbed moisture within the pores. As the temperature increased beyond 300 °C, the MB showed the greatest mass loss, which is a trend consistent with previously reported findings16. In addition, because biochar is a carbonized material that already has undergone pyrolysis, the mass loss observed in the 150 °C to 200 °C range can be interpreted as an indirect indicator of residual moisture content. Within this temperature range, the mass loss follows the order of wood > manure > husk, which corresponds to the initial moisture absorption trend observed on days 1 and 2 of the moisture absorption test. These results confirm that the initial moisture retention characteristics of biochar can be quantified indirectly through TGA. For all three types of biochar used in this study, the total mass loss below 200 °C remained within 5%, indicating that the materials maintained a thermally stable structure within this temperature range10,26.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

Figure 6 shows the XRD analysis results, where the crystalline structures of each sample were identified based on the SEM–EDX spectrometry results and comparison with the XRD library. Figures 6 (a) and (c) show strong diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 29.36 °C and 29.44 °C, respectively, corresponding to the main peaks of CaCO₃ (calcite). In contrast, Fig. 6 (b) shows the strongest peak at 2θ = 21.92 °C, which aligns with the main diffraction peak of SiO₂ (cristobalite). The HB presents a different crystalline phase compared to the other two types, likely due to its higher silicon and lower calcium contents. These differences in crystal structure are considered to be related to variations in the thermal treatment conditions and the elemental composition of the raw materials.

The biochar samples used in this study, produced from wood, husk, and manure, are carbonized materials obtained through pyrolysis. The XRD library search results revealed that some samples exhibit crystalline structures that are similar to those of CaCO₃ and SiO₂. Researchers have reported that these components contribute positively to the strength development of cement and concrete27,28.

Flow and compressive strength test results

Figure 7 shows the flow test results of the cement mortar, analyzed in conjunction with the previously conducted BET analysis, TGA, and moisture absorption tests. For example, as shown in Fig. 5 (a), the WB sample exhibited greater moisture absorption capacity than the HB sample, which corresponds to a more significant reduction in flow value for the WB specimen. The mortars with WB and HB exhibited flow reduction of 5.4% and 2.7%, respectively, indicating a decline in workability due to the biochar substitution. In contrast, the mortar with MB showed a flow increase of up to 43% compared to the plain (with no biochar) specimen, indicating enhanced workability.

According to the BET analysis results presented in Table 4, the HB and WB exhibited relatively large specific surface areas of 86.8 m²/g and 64.0 m²/g, respectively, along with small average pore diameters of 2.70 nm and 3.36 nm, respectively. These characteristics suggest a pore structure that is capable of effectively retaining moisture within the particles. This interpretation is supported by the TGA results, which show a gradual weight loss in the temperature range of 150 °C to 200 °C, indicating that moisture remained within the internal structure of the particles. Such internal moisture retention characteristics likely led to the absorption of available mixing water by the biochar during the mortar preparation, thereby reducing the effective water content and consequently lowering the flow values. This result is consistent with the findings of Pyo et al.29, who reported that the high carbon content and well-developed pore structure of wood-based biochar improve its ability to retain moisture. This enhanced moisture retention reduces the amount of free water in the fresh mortar mix, which consequently lowers the flow value and affects workability.

In contrast, despite the fact that the MB exhibited the second-highest moisture retention capacity in the early stages of the moisture absorption tests, and as indicated by the TGA results, the MB showed a tendency to increase the flow in actual mortar mixtures. The MB has the largest specific surface area at 5.23 m²/g, the largest average pore diameter of 11.9 nm, and the smallest total pore volume compared to the WB and HB specimens. These results indicate that the moisture in this type of biochar is retained primarily on the external surface rather than within the internal pore structure, making it more prone to release during mixing.

Figure 3 (e) shows that the MB has a rough particle surface, which also appears to have contributed to its flowability. Researchers have reported that the surface morphology of biochar can influence the workability of mortar15. In addition, as illustrated in Fig. 2 (c), the presence of larger particles in the MB may have replaced some of the finer cement particles, thereby increasing the flowability of the mortar mix13. These findings confirm that flow behavior is not determined solely by the amount of moisture absorbed but rather by a combination of the various physical properties of the biochar, including the moisture retention, pore size and volume, specific surface area, and particle morphology.

Table 5; Fig. 8 present the compressive strength results of the cement mortar specimens that contain biochar. The plain specimens (with no biochar) exhibited compressive strength values of 26.6 MPa and 31.3 MPa at 7 and 28 days, respectively. The specimens with WB (WB_5%) and HB (HB_5%) show strength values of 27.5 MPa and 32.0 MPa at 7 days and 40.3 MPa and 40.2 MPa at 28 days, respectively, indicating an increase in compressive strength compared to the plain specimens at both curing ages. This enhancement is considered to result from the filler effect of fine biochar particles below a certain size, which improves the microstructure of the cement matrix and contributes to the strength development of the mortar6,21.

At 7 days of curing, the compressive strength of the WB specimens was measured at 27.5 MPa, while a higher strength value of 32.0 MPa was recorded for the HB specimens. However, by 28 days, the values converged, with the WB and HB specimens showing compressive strength values of 40.3 MPa and 40.2 MPa, respectively. This outcome indicates that the WB specimens initially absorbed more moisture than the HB specimens, which delayed early hydration. However, the internally retained water was released gradually during the later curing period, which promoted internal curing and contributed to long-term strength development8,29,30.

The XRD analysis revealed the presence of residual CaCO₃ in the WB and SiO₂ in the HB. These components are considered to have influenced the strength development in the mortar specimens27,28. CaCO₃ is considered to contribute through its filler effect and the possible formation of carboaluminate by reacting with C₃A, while SiO₂ may have contributed to the strength enhancement through potential pozzolanic reactions. These mechanisms should be verified through further chemical analysis in future studies. In contrast, the mortar specimens that incorporated MB exhibited reduced compressive strength across all curing ages, with a strength decrease of approximately 44% compared to the plain specimen at 28 days. The MB specimens also showed a marked increase in flow value during the flow test, indicating that the biochar had little to no moisture absorption capacity during the initial mixing stage. The MB specimen’s small specific surface area, large average pore diameter, and low pore volume together suggest insufficient internal moisture retention. These characteristics, which include limited internal moisture retention, rough particle surface, and heterogeneous PSD, are considered to have collectively contributed to the observed reduction in compressive strength of the MB specimens. Overall, these findings confirm that the physicochemical properties of each biochar type, such as pore structure, surface area, and chemical composition, influence the compressive strength performance of the mortar.

Conclusion

In this study, domestically produced wood (WB), rice husk (HB), and manure (MB) biochar were applied as cement replacement admixtures, and the relationship between their physical and chemical properties and the mechanical performance of cement mortar was analyzed. The conclusions are as follows.

-

1.

Based on PSD, BET, SEM, and SEM–EDX analyses, WB and HB exhibited PSD results similar to ordinary cement, high porosity, and relatively large specific surface areas, whereas MB had the largest average particle size, lowest specific surface area, and higher inorganic content.

-

2.

The results of the moisture absorption test and flow test showed that HB had the lowest moisture absorption, WB was intermediate, and MB had the highest. The WB and HB mortars showed decreased flow values due to internal moisture retention, while MB exhibited increased flowability because of low moisture retention and poor particle characteristics. It was determined that these behaviors were influenced by multiple factors, including pore structure and particle morphology.

-

3.

The compressive strength test results indicated that WB and HB mortars showed strength improvement of up to 29% at both 7 and 28 days compared to plain mortar, possibly due to internal curing and the filler effect. In contrast, MB caused a significant reduction in compressive strength by approximately 44% and is therefore considered unsuitable for use as a cement replacement admixture.

For future studies, it is recommended to conduct quantitative analyses to clarify whether the strength improvement primarily results from internal curing or the filler effect, to determine the optimal replacement levels for different biochar types, and to evaluate additional mechanical properties and durability performance at the concrete scale.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

References

Kim, B-C. & Shin, E-C. Analysis of the EU green deal and just transition mechanism: A focus on the implementation of the just transition fund regulation. Korean J. Social Sci. 42 (3), 215–249 (2023).

Kumar, S., Gangotra, A. & Barnard, M. Towards a net zero cement: strategic policies and systems thinking for a low-carbon future. Curr. Sustainable/Renewable Energy Rep. 12 (1), 5 (2025).

Zhou, Z., Wang, J., Tan, K. & Chen, Y. Enhancing Biochar impact on the mechanical properties of cement-based mortar: an optimization study using response surface methodology for particle size and content. Sustainability 15 (20), 14787 (2023).

Lehmann, J. A handful of carbon. Nature 447 (7141), 143–144 (2007).

Weber, K. & Quicker, P. Properties of Biochar. Fuel 217, 240–261 (2018).

Han, S. M. & Choi, W. C. Evaluation of the mechanical properties of cement mortar containing wood-based bio-char. J. Korea Concrete Inst. 35 (3), 285–292 (2023).

Bhatia, S. K. et al. Trends in renewable energy production employing biomass-based Biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 340, 125644 (2021).

Choi, W. C., Yun, H. D. & Lee, J. Y. Mechanical properties of mortar containing Biochar from pyrolysis. J. Korea Inst. Struct. Maintenance Inspection. 16 (3), 67–74 (2012).

Gupta, S. & Kua, H. W. Carbonaceous micro-filler for cement: effect of particle size and dosage of Biochar on fresh and hardened properties of cement mortar. Sci. Total Environ. 662, 952–962 (2019).

Suarez-Riera, D. et al. The effect of different biochar on the mechanical properties of cement-pastes and mortars. Buildings 13(12), 2900 (2023).

Cantrell, K. B., Hunt, P. G., Uchimiya, M., Novak, J. M. & Ro, K. S. Impact of pyrolysis temperature and manure source on physicochemical characteristics of Biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 107, 419–428 (2012).

Lehmann, J., Gaunt, J. & Rondon, M. Bio-char sequestration in terrestrial ecosystems: A review. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Change. 11, 403–427 (2006).

Maljaee, H. et al. Effect of cement partial substitution by waste-based Biochar in mortars properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 301, 124074 (2021).

Tan, K. et al. Biochar from waste biomass as hygroscopic filler for pervious concrete to improve evaporative cooling performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 287, 123078 (2021).

Aziz, M. A., Zubair, M., Saleem, M., Alharthi, Y. M., Ashraf, N., Alotaibi, K. S., Aga, O., and Al Eid, A. A. A. (2023). Mechanical, non-destructive, and thermal characterization of biochar-based mortar composite. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery.

Akhtar, A. & Sarmah, A. K. Novel biochar-concrete composites: Manufacturing, characterization and evaluation of the mechanical properties. Sci. Total Environ. 616, 408–416 (2018).

Gupta, S., Kua, H. W. & Koh, H. J. Application of Biochar from food and wood waste as green admixture for cement mortar. Sci. Total Environ. 619, 419–435 (2018).

KS L 5122. Standard Guide for Evaluation of Alternative Supplementary Cementitious Materials (ASCM) for Use in Cement and Concrete (Korea Industrial Standards, 2024).

ASTM C109/C109M-20b. Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA. (2020).

ASTM C1437-13. Standard Test Method for Flow of Hydraulic Cement Mortar. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA. (2020).

Elyamany, H. E., Abd Elmoaty, M. & Mohamed, B. Effect of filler types on physical, mechanical and microstructure of self-compacting concrete and flowable concrete. Alexandria Eng. J. 53 (2), 295–307 (2014).

Li, J. et al. Comparative study for microcystin-LR sorption onto Biochars produced from various plant-and animal-wastes at different pyrolysis temperatures: influencing mechanisms of Biochar properties. Bioresour. Technol. 247, 794–803 (2018).

Yang, Y. et al. Qualities and quantities of poultry litter Biochar characterization and investigation. Energies 17 (12), 2885 (2024).

Spokas, K. A. Review of the stability of Biochar in soils: predictability of O:C molar ratios. Carbon Manag. 1 (2), 289–303 (2010).

Muthukrishnan, S., Gupta, S. & Kua, H. W. Application of rice husk Biochar and thermally treated low silica rice husk Ash to improve physical properties of cement mortar. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 104, 102376 (2019).

Kaikiti, K., Stylianou, M. & Agapiou, A. Development of food-origin biochars for the adsorption of selected volatile organic compounds (VOCs) for environmental matrices. Bioresour. Technol. 342, 125881 (2021).

Ali, M., Abdullah, M. S. & Saad, S. A. Effect of calcium carbonate replacement on workability and mechanical strength of Portland cement concrete. Adv. Mater. Res. 1115, 137–141 (2015).

Zhuang, C. & Chen, Y. The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: A review. Nanatechnol. Reviews. 8 (1), 562–572 (2019).

Pyo, M., Kim, J., Seok, S., Park, C. H. & Choi, W. Wood-Based Micro-Biochars in a cement mixture. Molecules 30 (9), 1898 (2025).

Gupta, S. & Kua, H. W. Effect of water entrainment by pre-soaked Biochar particles on strength and permeability of cement mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 159, 107–125 (2018).

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant, funded by the Korean government. (No. RS-2024-00408370)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, W.C.; methodology, W.C. and H.Y.; data curation, S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K. and W.C.; writing—review and editing, H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, SB., Yun, HD. & Choi, W. Feasibility on diverse biochars as supplementary cementitious materials. Sci Rep 15, 40732 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24618-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24618-z