Abstract

With the increasing complexity of space missions, the accuracy and efficiency of orbital maneuver planning have become crucial. This paper proposes an analytical derivation-based method for generating orbital maneuver solution sets to address the maneuver planning problem for spacecraft on-orbit services under J2 perturbation. By establishing an analytical relative motion model corrected for J2 perturbation, this method enables the rapid generation of maneuver solution sets that satisfy multiple constraints, providing diverse options for the initial mission planning phase. Simulation validation demonstrates that the method maintains good applicability across mission scenarios at different orbital altitudes. The generated solution sets not only enhance the flexibility of orbital maneuver planning but also provide a quantitative basis for optimizing the selection of mission timing windows, holding certain application value in scenarios such as space debris removal and on-orbit maintenance services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the continuous expansion of human space exploration activities and the growing complexity of the space environment, the safe management of space debris and operational spacecraft has become a global concern. These high-velocity space debris and uncontrolled cooperative spacecraft pose significant threats to critical space assets such as satellites and the International Space Station (ISS) in orbit. They not only increase collision risks but may also lead to damage or complete failure of critical technological infrastructure. Consequently, effective management and servicing of space debris, as well as defunct or decommissioned cooperative spacecraft, have become urgent priorities. This is crucial not only for the long-term sustainability of the space environment but also for ensuring the safety and efficiency of future space exploration and utilization.

Against this backdrop, the development of spacecraft on-orbit servicing technologies has become particularly critical. The core of this technology lies not only in accurately calculating the velocity increment (\(\Delta v\)) required to transfer from one orbital position to a predetermined target orbit but also in formulating optimal maneuver strategies. Such strategies must comprehensively consider when to execute orbital maneuvers to maximize fuel savings while satisfying terminal constraints to ensure efficient and safe orbital transfers. Traditional research has predominantly focused on identifying optimal control strategies to achieve the most economical or rapid maneuver scenarios1,2.

In existing research on orbital maneuver strategies, scholars often employ the Clohessy-Wiltshire (CW) equations for modeling due to their simplicity in simulating close-range maneuver scenarios3. Simultaneously, the development of high-precision relative motion theories incorporating dominant perturbation factors like J2 is an active direction in current academia4,5. Stupik et al.6 introduced the LVLH (local-vertical local-horizontal) rotating coordinate system into spacecraft on-orbit servicing and provided a CW equation-based description model. Under this framework, they constructed a closed-loop feedback controller for spacecraft servicing using the kriging method. Wang et al.7 investigated proximity satellite interception guidance strategies under the CW equations and discussed their saddle point solutions. Building on this, Ye et al.8 transformed the optimal control problem of saddle point solutions into a two-point boundary value problem (TPBVP) and solved it using heuristic search and Newton’s method. Zhang et al.9 proposed a free-time optimal guidance law generation method based on co-state normalization techniques and deep neural networks, ensuring solution uniqueness in specific scenarios. Given the computational advantage of the Clohessy-Wiltshire (CW) equations, they have been widely adopted in spacecraft on-orbit servicing research10. For non-zero-sum game problems under complete and incomplete information, Zheng et al.11 proposed an on-orbit servicing control strategy. They optimized the control gains of the servicing spacecraft through Q-learning and Riccati recursive algorithms, ultimately validating the strategy’s effectiveness.

Although the CW equations significantly simplify the modeling and analysis of spacecraft relative motion near circular orbits, their inherent simplifications, particularly the neglect of orbital perturbations, greatly limit their accuracy in mission scenarios. For scenarios requiring higher precision, the J2 perturbation effect must be considered to more accurately capture the relative motion states between spacecraft. Since Earth is not a perfect sphere, the J2 perturbation in its gravitational field alters spacecraft orbital parameters, including long-term variations in inclination, right ascension of the ascending node (RAAN), and argument of perigee12. These perturbation effects accumulate over time, potentially causing orbital deviations from intended paths and increasing mission uncertainties and complexities. Current research on satellite relative motion under J2 perturbations primarily focuses on solving precise orbit control problems for on-orbit servicing missions. Schaub and Alfriend13 proposed an analytical method for maintaining invariant relative orbits in a J2 environment, providing an important theoretical foundation for long-term orbit maintenance and initiating new approaches for relative motion design in perturbed environments. Building on this, Gim and Alfriend14 designed a high-precision state transition matrix, significantly improving the predictive capability for relative motion under J2 perturbation and laying a solid foundation for subsequent control algorithm design. In guidance and control, Breger and How15 proposed an online, safe, and fuel-optimized rendezvous trajectory method, systematically addressing collision avoidance issues in close-proximity operations and establishing a complete constraint handling framework for autonomous rendezvous missions. In recent years, Morgan et al.16 systematically applied convex optimization techniques to spacecraft trajectory planning, providing effective numerical tools for solving multi-constraint orbital maneuver problems under J2 perturbation. Sun et al.17 further applied robust control theory to orbit control in uncertain perturbation environments, demonstrating a new trend towards adaptivity in this field. These systematic studies provide solid technical support for on-orbit servicing tasks in J2 perturbation environments, while also highlighting the significant value of developing efficient analytical solution methods.

With the increasing diversification of space mission requirements and the growing complexity of the space environment, single-objective optimal control strategies for spacecraft missions are struggling to meet modern challenges. Most existing research focuses on determining the optimal velocity increment for orbital transfer, typically prioritizing single metrics such as fuel efficiency or time minimization. However, during critical phases of missions like on-orbit servicing and debris removal, such as close-range observation and proximity operations, illumination conditions transition from an environmental factor to a decisive constraint. Specifically, the effective operation of optical navigation systems and sensitive payloads strongly depends on the illumination of the space debris or its specific parts: in shadowed regions, optical sensors cannot image effectively, affecting the accurate judgment of target attitude and structure. Furthermore, to ensure the safety and precision of operations like on-orbit docking, mission planning must ensure that the operational area is under suitable illumination conditions to avoid risks associated with visual blind spots. When faced with such dynamic constraints directly related to mission success, along with multiple requirements like terminal distance and fuel limitations, traditional single-objective optimization methods appear inadequate due to their lack of adaptability.

To overcome these limitations, this study proposes a new computational framework for generating multiple feasible solution sets for spacecraft orbital transfer under J2 perturbation. Unlike traditional methods that specifically pursue minimum-fuel strategies, this method uses analytical computation to rapidly generate a series of impulsive solution sets that satisfy complex mission constraints (including proximity trajectories with specific illumination requirements) and establishes an explicit mapping between the velocity increment and the terminal position. This allows decision-makers to intuitively evaluate the trade-off between fuel cost and mission reliability. The framework further possesses the capability to dynamically plan maneuver strategies and trajectory pointing under complex constraints. Specifically, it can provide analytical trajectory design solutions for typical on-orbit servicing scenarios such as “approaching a non-cooperative target from a specific, well-lit direction to ensure continuous and stable operation of the optical navigation system”. For any given scenario, considering J2 perturbation, this method can analytically determine the set of velocity increments required to transfer the spacecraft from the initial state to the desired terminal position, thereby providing a flexible and reliable solution set for dynamic mission requirements.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section II first models the mission scenario involving two impulsive-thrust spacecraft. Section III details the analytical derivation process of the multi-solution-set maneuver strategy for spacecraft on-orbit services under J2 perturbation. Section IV presents numerical simulation results under different scenarios, analyzing the impact of varying termination times on the number of feasible maneuver solutions. Finally, conclusions are provided in Section V.

Scenario modelling

Scenario description

This study focuses on the problem of generating maneuver solution sets for spacecraft on-orbit services. To ensure the practicality and feasibility of the derived maneuver strategies, the mission scenario must incorporate several key realistic constraints. The main considerations include: the inherent maneuverability limitations of the spacecraft, the dependency of optical sensors on solar illumination, and stringent fuel budgets. The analysis is based on the following fundamental assumptions:

Assumption 1

The relative distance between the two spacecraft in the mission scenario is much smaller than the orbital radius, satisfying the conditions for the Clohessy-Wiltshire (CW) equations. This allows the application of a linearized relative dynamics model, significantly simplifying the initial analysis and solution derivation.

Assumption 2

The servicing spacecraft instantaneously acquires the velocity increment from an impulsive maneuver at the maneuver point. This idealized treatment is common in preliminary mission design, aiming to separate translational maneuver planning from complex propulsion system dynamics.

Assumption 3

The spacecraft has limited maneuverability, meaning there is an upper limit to the velocity increment achievable by a single impulsive control, termed the maximum single-impulse velocity increment. This constraint reflects the physical limits of the spacecraft’s propulsion system and is crucial for generating realistic and feasible maneuver schemes.

Based on the above problem definition and fundamental assumptions, the subsequent sections will establish the relative motion dynamics model. This model will serve as the mathematical foundation for deriving analytical maneuver solutions under the given constraints.

Relative motion dynamics modelling

In free-time on-orbit servicing missions, it is typically assumed that the relative distance between the servicing spacecraft and the target spacecraft is much smaller than the radius of the target orbit, and the target spacecraft operates in a near-circular orbit. Under this premise, the target orbital coordinate system—the Local-Vertical-Local-Horizontal (LVLH) frame—is adopted to describe the relative motion states of the two spacecraft18, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Here, the x-axis points from the Earth’s center towards the target spacecraft’s center of mass; the z-axis is perpendicular to the target orbital plane, along the direction of the orbital angular momentum vector; the y-axis lies within the orbital plane, forming a right-handed Cartesian coordinate system with the x-axis and z-axis; the coordinate origin O is located on the target spacecraft.

The control model for orbital maneuvers is developed using the state transition matrix of the CW equations in the LVLH frame:

Equation (1) describes the general relative motion dynamics under multi-impulse control. When the number of maneuvers is 1 (i.e., i = 1), this model reduces to the single-impulse maneuver scenario studied in this paper. The solution methods and numerical simulations in subsequent Sections III and IV are all based on this single-impulse assumption.where\({\text{X}}(t)=[x,y,z,\dot {x},\dot {y},\dot {z}]\)is the spacecraft’s state vector in the LVLH frame; \({\text{X}}({t_0})\)is the initial state of the spacecraft; t0 denotes the initial time; ti denotes the time of the i-th impulsive maneuver; t denotes the current time; \(\Delta {\text{v}}({t_i})=[\Delta {v_x},\Delta {v_y},\Delta {v_z}]\) denotes the impulse velocity increment applied by the servicing spacecraft at the moment of ti; \({{\varvec{\Psi}}}(t,{t_0})\) and \({{\text{\varvec{\Psi}}}_v}(t,{t_i})\) are input-response matrix for relative motion dynamics, and the expressions are as follows:

In the above equation, \(\Delta t=t - {t_0}\); \(\Delta {t_i}=t - {t_i}\); \(\mu\)is the Earth’s gravitational parameter, with a value of 3.986012 × 1014; \(n=\sqrt {\frac{\mu }{{{r^3}}}}\) is the mean orbital angular velocity of the servicing spacecraft. According to the above equations, given a fixed transfer time, the spacecraft’s position vector under any specified impulsive velocity increment can be obtained.

Assuming the target spacecraft executes a single orbital maneuver, the governing equations can be reformulated as:

included among these:

\({{\text{r}}_p}=[{x_p},{y_p},{z_p}]\) is the position vector of the servicing spacecraft after the orbit maneuver,\({{\text{X}}_p}=[{x_{p0}},{y_{p0}},{z_{p0}},{\dot {x}_{p0}},{\dot {y}_{p0}},{\dot {z}_{p0}}]\) is the initial state vector of the servicing spacecraft. From this equation, a velocity increment satisfying the conditions can be derived for any given terminal position.

More generally, the equation accounts for the effect of a single orbital maneuver on the terminal position vector. When multiple maneuvers are executed, the spacecraft’s state propagation between consecutive maneuvers is described by:

\({\text{X}}({t_i}^{ - })\) and \({\text{X}}({t_i}^{+})\) represent the state vectors of the spacecraft before and after the impulse control at ti moment, respectively. Equation (6) describes the spacecraft’s propagation process from one impulsive control to the next. Thus, the entire mission scenario can be decomposed into multiple single-maneuver problems, forming a sequential decision-making process.

Impulse spacecraft on-orbit service model

Unlike the traditional on-orbit service problem, the impulsive orbital transfer scenario introduces distinct challenges requiring explicit modeling of discrete control actions. This formulation emphasizes finite impulses (e.g., single-impulse velocity increment limits \(\Delta {v_{\hbox{max} }}\)), precise timing constraints between maneuvers, and deterministic state propagation under J2 perturbations.Modelling in the impulsive orbit transfer scenario requires full consideration of the above characteristics.

Spacecraft manoeuvrability constraints

In this study, the maneuverability of the spacecraft is characterized by the total velocity increment provided by a single impulsive maneuver. Based on practical engineering considerations, there is an upper limit to the total velocity increment obtainable from a single orbital maneuver, denoted as the maximum \(\Delta {v_{\hbox{max} }}\). This constraint applies to the magnitude of the velocity increment vector, meaning the velocity increment components of the servicing spacecraft in the x, y, and z directions (denoted by the symbols \(\Delta v_{x}^{{{t_i}}}\), \(\Delta v_{y}^{{{t_i}}}\), \(\Delta v_{z}^{{{t_i}}}\) respectively) must collectively satisfy the following equation:

Solar illumination constraints

In fact, in the geosynchronous orbit, satellites carry out observations of other satellites frequently19.Therefore, When a servicing spacecraft needs to perform proximity observations of space debris, meeting specific illumination conditions at the terminal phase is critical to ensuring the successful execution of on-orbit servicing missions. Typically, the illumination constraint is defined as the angle between the relative line-of-sight (LOS) direction from the servicing spacecraft to the target spacecraft and the solar incidence direction. As shown in Fig. 2:

where \(\theta\) is the angle between the sun vector reS and the relative position vector rpe of the two spacecraft at the terminal moment, indicating the solar illumination angle of the servicing spacecraft to the target spacecraft; \({{\text{r}}_{eS}}(t)\), \({{\text{r}}_{pe}}(t)\)represent the position vectors of the target spacecraft and the Sun, and the servicing spacecraft at any time t, respectively; and \({\theta _{l} }_{{im}}\) indicates the maximum solar illumination angle required for mission success.

Termination conditions

According to the mission scenario settings, the relative positions of the two spacecraft at the termination moment are typically required to meet certain constraints. The terminal target set is defined as follows:

Here,\({r_{\hbox{max} }}\)and\({r_{\hbox{min} }}\)represent the maximum and minimum distance tolerances for mission success, respectively.

Impulse on-orbit service model

In summary, for the impulsive thrust spacecraft on-orbit service scenario, the relative motion relationship is established by comprehensively integrating constraints such as orbital dynamics, spacecraft maneuverability (7), solar illumination (8), and terminal distance (9). This forms the impulsive spacecraft on-orbit service model, which is essential for ensuring the successful execution of on-orbit servicing missions. The integration of these constraints allows for a more accurate and efficient planning of spacecraft maneuvers, taking into account the complex dynamics and operational requirements of spacecraft in orbit. By considering these factors together, we can optimize the trajectory and control strategies, ensuring that the spacecraft can reach the desired position and orientation while adhering to mission constraints and safety requirements. This approach not only enhances the precision of the mission planning but also improves the overall efficiency and reliability of the spacecraft’s operations in the challenging space environment.

Analytical relative motion dynamics with J2 perturbation

Equation (1) neglects the effects of Earth’s J2 perturbation and represents the classical relative motion equations. However, when mission durations are long or high precision is required, this model often fails to meet mission requirements. To address this, Samuel A. Schweighart enhanced the classical CW equations by incorporating J2 perturbation accelerations into the relative motion dynamics model, improving its accuracy for circular/near-circular orbits20. The refined relative motion dynamics equations are as follows:

where the parameters are related as shown in the following equation:

\(\varepsilon\) is the initial phasing angle for the cross-track motion, \(R_{e}^{{}}\) is the Earth’s radius,\({i_{{\text{ref }}}}\) is the orbital inclination of the reference orbit, \(r_{{{\text{ref }}}}^{{}}\)is the orbital radius of the reference orbit, \({i_{{\text{sat1 }}}}\)is the orbital inclination of the servicing spacecraft, \({\dot {\Omega }_{{\text{ref }}}}\)is the rate of change of the right ascension of the ascending node (RAAN) for the reference orbit, \({\dot {\Omega }_{{\text{sat1}}}}\)is the rate of change of the RAAN for the servicing spacecraft.

Theoretically, the relative motion equations under J2 perturbation are transcendental equations that cannot be solved analytically using conventional methods. For high-orbit spacecraft, the semimajor axis and inclination variations under J2 perturbation are minimal and can be approximated as constants21. Thus, it is reasonable to assume these parameters as constants, set to the mean orbital elements of the spacecraft.

\(\bar {a}\),\(\bar {i}\) are the mean semi-major axis and orbital inclination of the reference spacecraft.Generally, GEO spacecraft exhibit small inclination and eccentricity, resulting in minimal positional changes relative to Earth. Based on practical engineering considerations, orbital maneuvers for such spacecraft primarily focus on orbit plane adjustments, with minimal changes to the z-axis position. Furthermore, according to Eq. (11), the relative motion along the z-axis is decoupled from the x-y plane, allowing for separate analysis. Therefore, in our analysis, we simplify the z-axis dynamics, while retaining the J2 perturbation effects for the x-y planar motion. In summary, the relative motion dynamics model of the two spacecraft under J2 perturbation is transformed into a form that emphasizes orbit plane adjustments with perturbation effects:

Therefore, the relative motion equation under J2 perturbation can be changed from an unsolvable transcendental equation to an analytic ordinary differential equation, and the above equation can be solved to obtain the three-axis motion equation as:

where,\([{x_0},{y_0},{z_0},{\dot {x}_0},{\dot {y}_0},{\dot {z}_0}]\)denotes the positional velocity of the servicing spacecraft in the target orbital coordinate system at the moment of t0,\([{\dot {x}_0},{\dot {y}_0},{\dot {z}_0}]=[\Delta {V_x}+{V_{x0}},\Delta {V_y}+{V_{y0}},\Delta {V_z}+{V_{z0}}]\),\([\Delta {V_x},\Delta {V_y},\Delta {V_z}]\) is the pulse increment applied at the instant of t0,\([{V_{x0}},{V_{y0}},{V_{z0}}]\)is the velocity of the spacecraft at the instant before the impulse increment is applied, and t is the time from the initial moment, according to Eq. (14), we can obtain the position of the servicing spacecraft with respect to the reference spacecraft at any moment.

To efficiently generate orbital maneuver solution sets, an inverse analytical relationship between the terminal state and the control input must be established. According to Eq. (14), by performing an inverse operation on the relevant state transition matrix, the explicit analytical relationship between the terminal relative motion state and the impulsive velocity increment can be obtained, as shown below:

\([M,N,U]\)is the position at which the servicing spacecraft is expected to arrive at the moment of termination. According to the above Eqs. (15)-(17), given the initial and termination state position vectors, the impulse increment required for orbit change, i.e., the maneuver strategy without considering the constraints, can be found.

Calculation process

To specifically illustrate the application mechanism of the proposed impulsive solution set construction method for spacecraft in specific scenarios, this section details the solution set generation process. The core idea is to systematically explore the solution space through analytical solutions: first, strategically select candidate maneuver timings and terminal times based on orbital geometric parameters—these parameters inherently have energy efficiency advantages—and then efficiently verify whether all candidate trajectories meet the actual constraints. By combining analytical dynamics derivation with multi-level constraint verification, this method can effectively screen feasible orbital maneuver schemes under J2 perturbation while satisfying fuel limitations, solar illumination conditions, and terminal distance constraints. The specific process is as follows:

In the table, the apsis time is the time when the true anomaly of the servicing spacecraft is 0 or π, and the orbital plane crossing time is the time when the dot product of the normal vector of the target orbital plane and the radius vector of the servicing spacecraft is zero. \(\rho\) represents the minimum distance during the approach phase. If the minimum distance falls below a predefined threshold, violating the collision avoidance constraint, the corresponding velocity increment is discarded. Meanwhile, in this scenario, apogee is selected as the default maneuver point for orbit transfer. This is because the velocity increment required for apogee maneuvers is minimized22, thereby optimizing the utilization of the spacecraft’s fuel and energy. Additionally, the terminal moment is selected as the orbital plane crossing time when the inter-spacecraft distance reaches its minimum, which helps reduce the energy consumption and time required for the maneuver. Based on the table above, feasible impulsive velocity increments can be rapidly identified, providing efficient multi-strategy planning support for missions such as debris removal and on-orbit maintenance.

Arithmetic example and discussion

In this section, a sampling-based approach is employed to solve the impulsive on-orbit servicing problem. First, an analytical impulsive on-orbit servicing model is established, yielding closed-form expressions for terminal position and required velocity increments. Then, tailored constraints for the mission scenario are designed, and sampling is used to solve for velocity increments corresponding to feasible terminal points, with results analyzed to overcome the limitations of traditional optimal solutions.

To validate the accuracy of the proposed analytical solutions and impulsive solution sets under mission-specific constraints, a geosynchronous Earth orbit (GEO) impulsive on-orbit servicing mission is considered. Using the analytical solutions introduced in Sect. 4 and a sampling approach for constraint-compliant terminal conditions, corresponding impulsive increment solutions are derived.

Simulation experiment parameters

To validate the spacecraft impulsive solution set construction method based on J2 perturbation compensation proposed in this paper, full-model simulations in realistic scenarios are required. To verify the accuracy of the method, three groups of experiments were designed, each with different initial states of the servicing spacecraft relative to the space debris. Among them, the high-orbit scenario models the space debris based on the orbital parameters of the real fragment INTELSAT 33E DEB, and the initial orbital altitude and inclination of the space debris in the low-orbit scenario are 700 km and 30°, respectively. The simulation experiments were run on an Intel Core i7-14650HX CPU @ 2.20 GHz with 16GB of memory. These experiments considered various initial conditions to comprehensively evaluate the robustness and adaptability of the method. The spatial states of the space debris and the servicing spacecraft at the initial time are shown in Table 1.

The simulation experiments establish an impulsive on-orbit servicing model based on practical space constraints such as fuel limitations, terminal distance, and solar illumination angle, and solve for the analytical solutions of impulsive increments under the given scenario. Detailed constraint parameter values are listed in Table 2:

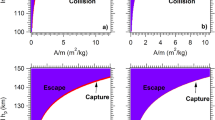

It is noteworthy that when the terminal time varies, the velocity increment required to achieve the mission objective is not unique for a given initial state of the servicing spacecraft. This means that for a specific mission scenario, there exists a solution set containing all feasible velocity increment strategies. To analyze the impact of terminal time selection on the number of solutions in the final orbital maneuver set, simulations were conducted for each scenario, starting from the maneuver time and using a series of subsequent orbital plane crossing times as terminal times.

By evaluating the influence of different terminal times on the solution set, this analysis provides additional options and flexibility for spacecraft orbit maneuver strategies. This is critical for optimizing spacecraft orbit maneuver planning, as it helps to understand how to achieve orbit maneuver objectives with minimal energy consumption under varying conditions. Through these simulation experiments, the proposed J2 perturbation compensation-based impulsive solution set method can be further validated and optimized to ensure its effectiveness and reliability in practical applications. Specific scenario settings are detailed in Table 3:

Simulation experiment results

In this study, the terminal positions of the servicing spacecraft that satisfy geometric constraints are determined based on the solar illumination angle and distance relative to the space debris at the terminal time. Since Eq. (14) describes the mathematical relationship between terminal states and required orbit increments, it is known from the analytical expression that each terminal position corresponds to a velocity increment. Considering the single available impulsive velocity increment, terminal states that do not meet velocity constraints are further filtered out. Through this process, a set of terminal states that satisfy both geometric and velocity constraints in practical scenarios is obtained. Based on these filtered and constraint-compliant terminal states, the velocity increments required to achieve these states can be further calculated.

In the analysis of Scenario 1, an exhaustive simulation of all possible impulsive solution sets was performed to determine the final orbital positions under different terminal time conditions. Specifically, the terminal distance step was set to 1 km, and the azimuth and elevation angles were refined with a 1-degree step, resulting in a total of 2,678,981 sampling points. Considering the constraints, the numbers of feasible impulsive increment solutions obtained under different terminal time conditions were 258,719, 512,975, and 40,547, respectively. Under the same sampling step size, similar simulation analyses were conducted for Scenarios 2, 3, and 4. As shown in Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6, the distributions of feasible maneuver solution sets at different approach times for Scenarios 1, 2, 3, and 4 are presented, respectively. These figures, through 3D and 2D views, clearly display the set of terminal positions satisfying all constraints, where the color depth of each point corresponds to the magnitude of the required velocity increment Δv, intuitively reflecting the spatial distribution characteristics of feasible solutions under different scenarios.

Analysis of results

A comprehensive comparison of the relationship between terminal time and the corresponding number of impulsive increment solutions for Scenarios 1, 2,3 and 4 is provided in Table 4:

After a comprehensive analysis of orbital maneuver strategies across multiple mission scenarios at different orbital altitudes (including high-orbit GEO scenarios and low-orbit LEO scenarios), we observed a significant cross-orbit regularity in the number of feasible solutions and fuel efficiency. For high-orbit scenarios, the optimal windows appear at 0.5 days, 1.5 days, and 2.5 days after the maneuver, which are odd multiples of the orbital semi-period. Similarly, in low-orbit scenarios, the optimal window appears at 9.5 h after the maneuver. Although the absolute time intervals differ in magnitude from those in high-orbit scenarios, the underlying orbital mechanics principle remains entirely consistent: when the flight time approaches an odd multiple of the orbital semi-period, both the number of feasible solutions and the fuel efficiency reach their optimum. This regular discovery makes the generated maneuver solution set itself a powerful decision-support tool, providing multi-level practical application value for mission planning.

Firstly, the number of feasible solutions is a direct indicator of the time window’s robustness. A larger solution set quantity implies greater flexibility in handling uncertainties during execution. Therefore, when mission robustness is highly required, planners can prioritize time windows with abundant solution sets (e.g., 1.5 days in Scenario 1); whereas when fuel efficiency is critical, the window with the minimum ΔV can be chosen.

Secondly, the clear mapping relationship between the velocity increment and the terminal relative position (as shown in Figs. 3, 4 and 5) allows for a preliminary qualitative assessment of the “cost” of approaching the target from different directions. For example, by analyzing the distribution of ΔV values required to approach different surfaces of the space debris, planners can quickly identify which approach directions are more fuel-efficient or feasible under given illumination constraints.

Furthermore, the solution set reveals the unreachable regions of the space debris under the current flight time and constraints. If there are no corresponding feasible solutions for certain azimuths under the illumination constraints, it means that approaching these faces of the space debris is infeasible under the current conditions. This characteristic enables the assessment of scheme feasibility in the early stages of the mission and guides the adjustment of initial conditions or mission requirements, thereby avoiding ineffective planning work.

This phenomenon indicates that specific time windows not only provide abundant feasible strategy choices but also guarantee minimized fuel consumption, presenting a dual advantage of “strategy diversity-fuel economy”. From a mission application perspective, these windows provide ideal operation opportunities for orbital maneuver planning characterized by high robustness and low cost, both enhancing the mission’s ability to cope with uncertainties and significantly improving execution efficiency. This discovery holds important guiding value for practical on-orbit servicing tasks, can provide a theoretical basis for selecting orbital maneuver timing under multiple constraints, and supports the rapid generation of mission plans that combine flexibility and optimality.

Discussion and verification

Model error and generality analysis

To systematically evaluate the applicable boundaries of the J2 perturbation analytical dynamics model for long-duration missions, this study conducted a comprehensive error analysis. By comparing with a high-precision nonlinear orbit propagator, the model’s accuracy performance in different orbital scenarios was quantitatively analyzed. The simulation covered two typical orbits: Geostationary Earth Orbit (GEO, semi-major axis 42,164 km) and Low Earth Orbit (LEO, semi-major axis 7,500 km). For each scenario, different initial relative distances (100 km, 500 km, 1,000 km) were set, and propagation was performed for up to 3 days to comprehensively evaluate the model’s performance under different operating conditions. The results are presented in Fig. 7; Table 5:

Figure 7 clearly shows the growth of the model’s position error over time. The analysis results indicate that in the GEO scenario, the accuracy is high; even after 3 days of propagation with a 1000 km initial separation, the maximum absolute error remains below 0.19 km. In the LEO scenario, where the J2 perturbation effect is more significant, the model’s accuracy still meets the requirements for preliminary mission design, with a maximum absolute error of 2.23 km under the same conditions.

To further quantify the combined influence of unmodeled higher-order perturbations (such as J₂² terms, solar radiation pressure, atmospheric drag, and third-body gravitational effects), we compared the absolute position accuracy of the J2 analytical model against a high-precision orbit predictor that includes a full force model. It should be noted that this phase of analysis focuses on the absolute orbital position accuracy of the spacecraft itself, to independently assess the completeness of the dynamics model.

The comparison results are shown in Fig. 8. In the GEO scenario, for an initial separation of 1000 km, the maximum position error after 3 days is only 0.26 km (relative error 0.026%). Even for the smallest initial distance of 100 km, the maximum error is only 0.03 km. This confirms the high reliability of the J2 analytical model for high-orbit missions.

In the LEO scenario, due to the increased effect of unmodeled perturbations like atmospheric drag, the errors are more significant. For a 1000 km initial separation, the maximum position error after 3 days is 1.78 km (relative error 0.178%). Although the error is larger compared to the GEO scenario, considering the significant computational efficiency advantage of this analytical method, the magnitude of this error remains within an acceptable range for the preliminary planning and rapid strategy generation of most on-orbit servicing missions.

In summary, the J2 analytical dynamics model achieves a good balance between accuracy and computational efficiency, making it particularly suitable for the preliminary design phase where mission duration is limited and a large number of feasible strategies need to be generated quickly. It should be noted that for missions requiring high precision over longer periods, the cumulative effect of unmodeled perturbations becomes increasingly important. In such application scenarios, it is recommended to perform trajectory fine-tuning using local optimization algorithms based on the initial solution set generated by the method proposed in this paper, to ensure the execution accuracy of the final mission.

Model accuracy and comparative verification

Furthermore, to ensure the reliability of the analytical method proposed in this paper in engineering practice, this section conducts a reverse numerical validation of the generated maneuver strategies. A high-precision orbital numerical integrator was used to re-integrate all feasible velocity increments (ΔV) obtained analytically for Scenarios 1, 2, 3, and 4 in Sect. 4.3. The integration started from the maneuver time and ended at the terminal time, to obtain the real terminal position corresponding to each ΔV strategy and re-evaluate whether it satisfies the terminal distance constraint (i.e., relative distance within the range of 10 km to 50 km). The verification results are illustrated in Figs. 9, 10, 11 and 12:

In the figure, the green points represent valid solutions that still satisfy the terminal constraints after verification by the high-precision model, while the red points represent invalid solutions that exceed the constraint range due to the accumulation of model errors. Quantitative statistical results show that in the three GEO scenarios, the validity ratios of the analytical solutions reach 98.1%, 98.2%, and 97.8%, respectively; while in the low-orbit Scenario 4, where perturbation effects are more significant, 92.2% of the analytical solutions still satisfy the constraints, fully verifying the practicality of this method in the preliminary mission design phase.

The above results indicate that although the dynamics model adopted in this paper undergoes necessary simplifications, it still demonstrates high reliability in real orbital environments, with the vast majority of analytical solutions serving as valid maneuver strategies. This characteristic makes the method suitable for rapidly generating a large number of feasible strategies and providing high-quality initial solution sets for subsequent high-precision optimization. Overall, the analytical method proposed in this study can generate maneuver strategy solution sets with reliability exceeding 92% for both GEO and LEO missions, meeting the requirements of preliminary mission design.

Conclusion

Building upon existing research in orbital maneuver planning, this paper proposes an analytical derivation-based method for generating impulsive maneuver solution sets. Its core innovation lies in breaking through the limitations of traditional single-optimal-solution strategies and constructing an efficient computational framework capable of systematically outputting sets of feasible trajectories under multiple constraints. By decoupling the processing steps for each sampling point—including terminal position calculation, illumination judgment, distance constraint checking, and impulsive increment verification—into independent tasks via the analytical model, computational efficiency is significantly enhanced, providing a technical foundation for real-time integration and rapid on-orbit planning. By introducing an analytical relative dynamics model corrected for J2 perturbation, this method significantly improves the accuracy of close-range relative motion prediction while maintaining computational efficiency. It should be noted that the model’s accuracy is subject to the linearization assumptions and the dominance of J2 perturbation; in very low orbits or over extended durations, higher-order perturbations may necessitate subsequent refinement. Despite this, the method demonstrates clear applicability boundaries across different orbital altitudes: in high-orbit (GEO) missions, the model error can be controlled within 0.2 km, fully meeting mission planning requirements; in the low-orbit (LEO) environment, although unmodeled perturbations (such as atmospheric drag) introduce certain errors, it still holds significant advantages for rapid strategy generation and preliminary scheme screening. The feasible solution sets generated by this method can serve as a multi-functional decision-making tool in practical mission design—mission planners can not only directly select approach trajectories satisfying specific illumination directions to support directed observation or optical navigation of space debris, but also assess the robustness of time windows based on the solution set size, or quickly identify fuel-optimal approach strategies based on the ΔV distribution. For example, in debris removal missions, decision-makers can directly select various pre-planned strategies from the solution set, such as “minimum fuel” or “highest solution density,” greatly enhancing the mission’s flexibility to cope with unexpected situations. This method provides a new planning approach for scenarios such as on-orbit services and non-cooperative target operations under complex constraints, combining speed, reliability, and decision transparency, effectively bridging the gap between theoretical design and engineering practice in orbital maneuvers.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Carter, T. E. State transition matrices for terminal rendezvous studies: brief survey and new example. J. Guid Control Dyn. 21, 148–155. https://doi.org/10.2514/2.4211 (1998).

Prussing, J. E. Optimal multiple-impulse Orbital Rendezvous (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1967).

Clohessy, W. H. & Wiltshire, R. S. Terminal guidance system for satellite rendezvous. J. Aerosp. Sci. 27, 653–674. https://doi.org/10.2514/8.8704 (1960).

Kapila, V., Sparks, A. G., Buffington, J. M. & Yan, Q. Spacecraft formation flying: dynamics and control. J. Guid Control Dyn. 23, 561–564. https://doi.org/10.2514/2.4567 (2000).

Schaub, H. & Alfriend, K. T. Impulsive feedback control to Establish specific mean orbit elements of spacecraft formations. J. Guid Control Dyn. 24, 739–745. https://doi.org/10.2514/2.4774 (2001).

Stupik, J., Pontani, M. & Conway, B. AIAA, Optimal pursuit/evasion of spacecraft trajectories in the hill frame of reference. in AIAA/AAS Astrodynamics Specialist Meeting 4882 (2012). https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2012-4882

Wang, Q., Ye, D., Fan, N. J. & Wu, Y. X. Terminal orbital control of satellite pursuit evasion game based on zero effort miss. Trans. Beijing Inst. Technol. 36, 1171–1176. https://doi.org/10.15918/j.tbit1001-0645.2016.11.014 (2016).

Ye, D., Shi, M. M. & Sun, Z. W. Satellite proximate pursuit-evasion game with different thrust configurations. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 99, 105715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ast.2020.105715 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Near-optimal interception strategy for orbital pursuit-evasion using deep reinforcement learning. Acta Astronaut. 198, 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2022.05.057 (2022).

Miele, A., Weeks, M. W. & Ciarcià, M. Optimal trajectories for spacecraft rendezvous. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 132, 353–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10957-007-9166-4 (2007).

Zheng, Z. X., Zhang, P. & Yuan, J. P. Nonzero-sum pursuit-evasion game control for spacecraft systems: A Q-learning method. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 59, 3971–3981, https://doi.org/10.1109/TAES.2023.3235873

Holzinger, M. J., Scheeres, D. J. & Erwin, R. S. On-orbit operational range computation using gauss’s variational equations with J2 perturbations. J. Guid Control Dyn. 37, 608–622. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.53861 (2014).

Schaub, H. & Alfriend, K. T. J2 invariant relative orbits for spacecraft formations. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astronomy. 79, 77–95. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011161811472 (2001).

Gim, D. & Alfriend, W. (ed T, K.) State transition matrix of relative motion for the perturbed noncircular reference orbit. Inamerican Astron. Soc. (AAS)/american Inst. Aeronaut. Astronaut. (AIAA) Space Flight Mech. Meeting https://doi.org/10.2514/2.6924 (2001).

Breger, L. How,et al. Safe trajectories for autonomous rendezvous of spacecraft. Journal of guidance. Control Dynamics. 31 (5), 1478–1489. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.29590 (2008).

Morgan, D., Chung, S. J. & Hadaegh, F. Y. Model predictive control of swarms of spacecraft using sequential convex programming. J. Guid Control Dyn. 37, 1725–1740. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.G000218 (2014).

Sun, L. et al. Robust adaptive control of spacecraft proximity maneuvers under dynamic coupling and uncertainty. Adv. Space Res. 56, 2206–2217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2015.08.029 (2015).

Henderson, D. M. C-W state transition matrix for LVLH relative motion.Appl. Cartes. Tensors Aerosp. Simul. (2006). https://doi.org/10.2514/5.9781600861567.0195.0196

Orchard, M. E. & Vachtsevanos, G. J. A particle filtering approach for on-line failure prognosis in a planetary carrier plate.Int. J. Fuzzy Log. Intell. Syst. 7, 221–227. https://doi.org/10.5391/IJFIS.2007.7.4.221 (2007).

Schweighart, S. A. & Sedwick, R. J. High-fidelity linearized J model for satellite formation flight. J. Guid Control Dyn. 25, 1073–1080. https://doi.org/10.2514/2.4986 (2002).

Zhang, Y. S., Xu, Y. L. & Yang Q.Spacecraft Orbit Theory and Applications (Tsinghua University, 2020). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Curtis, H. D.Orbital Mechanics for Engineering Students (Elsevier, 2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X; S.Z; Y.Z; methodology and software validation Y.J; Y.Z; X.T; formal analysis and writing—original draft, Y.Z; J.X; writing—review and editing, J.X; Y.Z; S.Z; X.T; visualization, S.Z; M.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, J., Zhao, S., Yang, M. et al. An analytical approach to generating orbital maneuver sets for spacecraft on-orbit services. Sci Rep 15, 40960 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24686-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24686-1