Abstract

The rise of generative artificial intelligence has prompted claims that large language models (LLMs) can substitute for human participants, particularly in moral judgment tasks where correlations between ChatGPT and humans approach r = 1.00. In response, we conducted a pre-registered study where two LLMs (text-davinci-003 and GPT-4o) predicted human moral judgments of 60 scenarios prior to a large human sample (N = 940) rating them. Despite strong correlations, difference scores revealed substantial, systematic errors: Compared to humans, LLMs provided more extreme morality ratings of moral and neutral scenarios and more extreme immorality ratings of immoral ones. Moreover, ChatGPT differed significantly and with moderate to large effect sizes from human averages on ~ 87% of scenarios. Further, LLM ratings clustered around a restricted number of values, failing to reflect human variability. Re-examination of earlier published data also reflected this clumping. We conclude that broader evaluation criteria are needed for comparing LLM predictions and human responses in moral reasoning tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To what extent can generative artificial intelligence (AI) large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT replicate the moral judgments of human participants? This question has relevance for a wide variety of fields including political science, psychological science, computational social science, and AI reliability. Previous research has indicated correlations between average human moral judgments and ratings produced by ChatGPT that approach 1.001, leading to suggestions that LLMs might at some point be used as a synthetic subject for moral judgment studies or be utilized as a valid means for pilot testing stimuli prior to their use with human participants2,3,4. Other researchers have been less optimistic, pointing to the need for additional research (particularly pre-registered experiments5, such as the one presented here) and more in-depth consideration of the possible limitations of AI6,7,8,9,10,11,12.

Past research has relied extensively on correlation as an indicator of agreement between LLMs’ ratings and human moral judgments1,13,14,15. However, correlation is an incomplete metric of agreement between variables, as it only assesses a linear relationship and ignores the size or nature of discrepancies. For instance, a dataset of {1,2,3,4,5} would correlate perfectly with {51,52,53,54,55}, yet every value differs by 50, demonstrating that correlation alone cannot capture large discrepancies between two datasets. This problem becomes even more pernicious if discrepancies are inconsistent across a continuum. For example, dataset {2,3,4,5,6,8,12,13,14,15} correlates with dataset {1,3,5,7,9,15,17,19,21,23} at r = 0.987, and yet each pair of values differs by anything from − 1 (e.g., 2 vs. 1) to 8 (e.g., 15 vs. 23).

To determine whether ChatGPT can validly predict average human judgments, we recruited a large sample of human raters (N = 940) to make moral judgments of 60 scenarios. To ensure variance across the 60 scenarios, a third of the scenarios featured moral behaviors, a third featured immoral behaviors, and a third featured morally-neutral behaviors. The human authors of the study wrote 30 of these scenarios specifically for this study to ensure that GPT ratings of the stimuli would not have been contaminated by past publication of data, an issue identified as a potential limitation of previous work1,16. We also prompted ChatGPT to write 30 scenarios. Prior to data collection from our human sample, GPT-3 (text-davinci-003) rated the 60 scenarios, and we pre-registered these ratings along with an a-priori power analysis in an OSF.io repository (see https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/6PF3X).

Because we are interested in the correspondence between average human moral judgments and GPT ratings, the level of analysis for the current study is at the scenario level, which is what we used to determine our a-priori power analysis. The 30 scenarios for each author source (resulting in 60 total scenarios) represents a well-powered study given the effect size reported by Dillion et al.1. In fact, a post-hoc sensitivity analysis using GPower (assuming α = 0.001, one-tailed, and power = 0.999) indicated that with 30 scenarios the minimum detectable effect size was ρ = 0.78, which is 82% of the original estimate (ρ = 0.95) provided by Dillion et al.1. Further, the large sample size of human participants who rated all scenarios provides stable mean estimates and minimizes sampling error.

To assess whether advancements in LLMs might increase accuracy, we also had a later model of ChatGPT (GPT-4o) predict the values for the 60 scenarios. Our pre-registration is limited to text-davinci-003. GPT-4o was released after we pre-registered our study and after Dillon et al.’s study1 that adopted a similar methodology.

Results

For all analyses, we aggregated responses to the scenario level. That is, we computed the average morality response for each scenario across all respondents and compared those to the morality ratings generated by each version of ChatGPT. Full analytical code and results are presented in the OSF.io online supplement.

Replicating earlier studies, ChatGPT’s moral evaluation scores correlated with average human judgments nearly perfectly (see Table 1; see Fig. 1). Correlations did not substantially differ between human-authored scenarios and GPT-authored scenarios.

Yet strong correlation alone is not sufficient to demonstrate that ChatGPT moral judgments mirror average human moral judgments. To better assess the level of agreement between ChatGPT and human moral judgments, we examined three discrepancy statistics: simple difference scores (i.e., ChatGPT prediction minus human average), absolute difference scores, and squared difference scores. The simple difference scores indicate whether ChatGPT is directionally biased from human judgments; the absolute difference scores indicate average magnitude of error; and the squared difference scores indicate how different each score is in squared terms (which rewards differences less than 1 and punishes differences greater than 1). We conducted six ANOVAs in which statement authorship (human authorship of statements vs. ChatGPT authorship of statements) served as the independent variable and the discrepancy statistics (simple, absolute, and squared difference scores for each of the GPT models) served as the outcome variables. The results did not find any significant differences in discrepancy statistics between scenarios written by humans or GPT (minimum p-value = 0.52; maximum η2 = 0.01). We thus combined reporting for the two scenario authorship sources.

We calculated the discrepancy statistics as average discrepancies across the 60 scenarios. We also calculated average discrepancy statistics for the moral, neutral, and immoral scenario subgroups. This subdivision is necessary for the simple difference score because positive and negative deviations could cancel each other out (e.g., if ChatGPT is biased positively for moral scenarios and biased negatively for immoral scenarios). It is also informative for the absolute and squared differences in order to examine the consistency of the discrepancies within the moral subsets. We then conducted one-sample t-tests on these average discrepancies to determine whether the discrepancies differed significantly from zero (see Table 2). We applied the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (BH-FDR) and Bonferroni-correction to account for multiple tests17. The Bonferroni-correction is a highly conservative correction intended to minimize false positives, whereas the BH-FDR rate is slightly less conservative and balances risks of false positives and false negatives. All simple discrepancies (except the text-davinci-003 average across all scenarios) were significantly larger than zero and associated with moderate to large effect sizes (Cohen’s d ranged from 0.41 to 2.12). We further note that both text-davinci-003 and GPT-4o are biased significantly positively for the moral and neutral scenarios (minimum Cohen’s |d|= 1.04) and significantly negatively for the immoral scenarios (minimum Cohen’s |d|= 1.35). We note the exceptionally large effect sizes associated with these biases. As indicated by the simple difference scores, ChatGPT produces substantially more extreme ratings of morality for both moral and neutral behaviors as compared to humans. Moreover, it also produces substantially more extreme ratings of immorality for immoral behaviors as compared to humans. These patterns reflect similar biases that have been observed by past research regarding the confidence of AI in its predictions when compared to humans18.

To further examine the discrepancies, we conducted one-sample t-tests on each individual scenario, again applying the BH-FDR and Bonferroni corrections. That is, we tested whether the average human judgment for each scenario differed from the GPT-generated morality rating for that scenario (i.e., the hypothesized value in the one-sample test). This approach complements the prior discrepancy analysis with the advantage of explicitly accounting for variability in human judgments for each scenario.

For text-davinci-003, the average absolute t-value was 17.57 (SD = 10.66, max = 48.00, min = 0.00), which greatly exceeds the standard significance cutoff of ± 1.96 (p < 0.05, two-tailed) for our sample size and the Bonferroni-corrected significance cutoff of ± 3.34. The average Cohen’s d was 0.57 (SD = 0.35, max = 1.57, min = 0.00), which is consistent with a large effect. With regard to the BH-FDR correction, 53 of the 60 scenarios significantly differed from the ChatGPT predicted value; this was reduced to 52 of 60 with the more conservative Bonferroni-correction.

For GPT-4o, the average absolute t-value was 13.78 (SD = 8.13, max = 32.67, min = 0.00). The average Cohen’s d was 0.45 (SD = 0.27, max = 1.07, min = 0.00). With regard to the BH-FDR correction, 56 of the 60 scenarios significantly differed from the ChatGPT predicted value; this was reduced to 52 of 60 with the more conservative Bonferroni-correction. In short, ChatGPT’s morality ratings (both text-davinci-003 and GPT-4o) diverge from average human ratings outside of what would be expected in relation to sampling error, and the effect sizes associated with these deviations represent moderate to large effect sizes in the social sciences. For visual reference, Fig. 2 plots the 95% confidence intervals for the human scores—as well as ± 4 standard errors (which capture more than 99.99% of the sampling distribution and exceeds the Bonferroni correction value)—alongside the ratings produced by text-davinci-003 and GPT-4o. The figure demonstrates the substantial lack of agreement (reflected by a lack of overlap of the confidence intervals/standard errors with the AI estimates) as well as the systematic biases discussed earlier (ChatGPT overestimates the morality of moral behavior and overestimates the immorality of immoral behavior compared to humans).

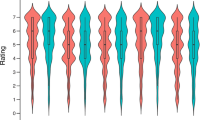

We further noted that ChatGPT’s predictions included only a small number of unique values (see Table 3). Rather than producing fine-grained variations across the 60 scenarios, ChatGPT attributed identical ratings (to the hundredth decimal point) to vastly different scenarios. For the 60 scenarios in the current study, text-davinci-003 only produced 9 unique values, which corresponds to only 6 unique absolute values. Moreover, 32 of the 60 scenarios were rated as either 3.99 (n = 19) or 2.45 (n = 13) by text-davinci-003. Examining GPT-4o’s ratings we found 16 unique values corresponding to only 14 unique absolute values. For GPT-4o, 23 of the 60 scenarios were rated as 3.12. The human means, on the other hand, reflected 57 unique values, corresponding to 50 unique absolute values. ChatGPT’s ratings thus do not reflect variation in unique values that characterize aggregated human data19. Instead, ChatGPT ratings clump onto a small number of unique values.

We re-analyzed the full data from Dillion et al. to determine whether the limited number of unique predictions was also present there (see Table 4). For the 464 scenarios in their dataset, ChatGPT (text-davinci-003) produced only 21 unique values, which corresponds to 15 unique absolute values. We also ran this dataset through GPT-4o, and it performed nominally better, producing 42 unique values, which corresponds to 32 unique absolute values. Still, the human data included far more variation with 287 unique values, which corresponds with 224 unique absolute values.

Discussion

Our results replicate the exceptionally strong correlation between AI ratings and human moral judgments1. Using scenarios specifically written for this study and a large human sample, we were able to rule out the alternative explanation that ChatGPT’s ratings correlated so strongly with human judgments because the original data were included in the training sets. LLMs thus seem particularly good at capturing constructs like morality at a coarse level, distinguishing moral from immoral.

However, LLMs’ ratings deviated considerably from human participants’ judgments in a systematic manner. Our analyses of three types of discrepancies, one-sample t-tests testing the significance of these discrepancies, and frequency tests examining the number of unique values produced by each source of data all provide diagnostic information for assessing whether AI ratings replicated human judgments. Based on these statistics, it becomes clear that the high correlation does not reflect ChatGPT being able to replicate aggregate human moral judgments. As generative AI models continue to develop and improve, researchers seeking to test new models’ ability to replicate human judgments might apply the statistical comparisons provided here in order to more comprehensively investigate AI’s prediction accuracy.

Beyond demonstrating how a sole reliance on correlations can be problematic, our findings contextualize how relying on estimates produced by ChatGPT might lead researchers astray. One use for ChatGPT suggested by previous research is as a pilot test for stimuli prior to their deployment in full studies1,3,4. A researcher might write a series of scenarios, ask ChatGPT to rate them, and then use the ratings to select specific scenarios for use in a full study. Our results show how this process could lead to problematic selections and wild goose chases. For example, the scenarios “A firefighter is taking his family on a vacation during some much needed R & R,” and “A firefighter organizes a potluck dinner with the proceeds being donated to a local charity. The dinner raises just over $1000,” were both rated at 3.12 on the scale by GPT-4o. However, these same scenarios were rated at 1.44 and 3.12 by humans, a difference of 1.68, which spans 18.7% of the available rating scale. A similar issue is further reflected in scenarios that humans judge very similarly but ChatGPT rates as vastly different. “A firefighter plays guitar at the fire station to entertain the crew during slow times,” and “A firefighter is filling out paperwork regarding the weekly calls” were rated by humans as 1.42 and 1.39. ChatGPT text-davinci-003 rated these as 2.45 and 0.45, respectively. A researcher deploying stimuli pretested in ChatGPT among real human participants might be surprised to find large differences between two scenarios that ChatGPT rated as identical to one another or to find small or even no difference between two scenarios that ChatGPT rated as vastly different.

Notably, our results indicate that discrepancies between human moral judgments and ChatGPT predictions are systematic rather than random. As seen in Table 2 with the simple difference scores, both ChatGPT models consistently rated immoral scenarios as more immoral than humans rated them and consistently rated neutral and moral scenarios as more moral than humans rated them. Although random errors might average out with a large corpus of stimuli, systematic errors will not. Thus, even if a researcher engaged in a stimulus sampling approach with a large number of ChatGPT pre-tested stimuli, systematic error would likely bias their results as compared to human data.

Our current investigation cannot speak to why ChatGPT exhibits these systematic discrepancies from human judgments. Future research, however, should consider that LLMs tend to agree with human end-users. Notably, because of the independence between the human ratings (i.e., means produced by a large human sample) and the output of the LLMs, it seems unlikely that the LLMs are attempting to amplify the beliefs or values of an individual end-user (i.e., the researcher who prompted the LLMs). It seems more likely that the LLMs are amplifying aggregate human biases in the training data (e.g., helping behaviors are good, harmful behaviors are bad). Future research could be conducted to help examine whether the biases in the training data could be reduced or eliminated—or even amplified—based on specific end-user inputs.

Although our current data casts substantial doubt on the ability of current ChatGPT models to accurately reflect human moral judgments, as LLMs continue to develop, future models may be better suited for such a task. When assessing the ability of generative AI models to predict human moral judgment, future research should consider metrics of agreement and discrepancy beyond correlation. To date, correlation seems to be the dominant metric used by researchers for assessing AI correspondence to human judgments, not only in the context morality, but also in other contexts such as sensory evaluations20. To be sure, we do not mean to suggest that correlations are worthless indications of agreement. They do offer relevant evidence regarding the consistency between two sets of information; however, we argue that this evidence provides an incomplete assessment of the overlap between the two sets of information and can even prompt misleading conclusions when taken in isolation. That is, if LLMs could replicate human cognition, they would produce judgments that strongly correlate with human judgments; however, caution is warranted when drawing the reverse inference that the presence of such a correlation is evidence that LLMs produce the same ratings that humans would. The metrics and methods applied in this paper demonstrate the shortcomings of relying purely on correlations and can serve as a starting point for considering alternative and complementary indicators of correspondence between AI models and human judgments.

Materials and methods

Prior to data collection, the study’s procedures were reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at The Ohio State University, and the study was determined to be exempt from IRB review (application 2023E0522). The experiment was performed in accordance with relevant institutional guidelines and regulations, and all participants were treated in a manner consistent with the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in the study.

Our approach was based on the Dillion et al. study1 with the explicit goal of establishing that ChatGPT can predict human responses before they have been generated. Our central hypothesis was that moral evaluation scores of behaviors generated by ChatGPT will correlate strongly with those generated by human participants.

A group of the co-authors wrote 30 scenarios describing a firefighter engaging in behaviors that were intended to be moral, immoral, or morally neutral. We also asked ChatGPT to generate 30 scenarios. The effect size reported in Dillion et al.1 was large (rho = 0.95). This correlation was based on 464 scenarios from 5 papers21,22,23,24,25. Because the level of analysis is at the scenario level (i.e., ChatGPT scores are correlated with the mean score from a human sample), the number of scenarios in the current study (30 per source with 60 total) greatly exceeds the number required (N = 4) to detect a correlation of rho = 0.95, with alpha = 0.05 (one-tailed), power (1-beta) = 0.95.

In generating ChatGPT predictions, we first used the OpenAI API to instruct ChatGPT to rate the 60 scenarios using the text-davinci-003 model. We consulted with co-authors of Dillion et al. who were most closely involved in prompting ChatGPT (personal correspondence) to ensure that our prompts and model parameters replicated theirs precisely (see ‘Files’ section of the OSF repository for this project; https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/9JW23). The prompting we used perfectly replicated the prompt Dillion et al.1 used, which is reproduced below:

-

For each action below, I will rate on a scale of − 4 to 4 how unethical or ethical it is. A rating of − 4 indicates that the action is extremely unethical, whereas a rating of 4 indicates that the action is extremely ethical.

-

Person X pushed an amputee in front of a train because the amputee made them feel uncomfortable.

-

[Rating]: − 3.78

-

Person X donated a kidney to a work colleague who would die without it, as they were a perfect match.

-

[Rating]: 3.51

-

Person X never learned how to ride a bicycle.

-

[Rating]: − 0.01

-

Person X has memorized three of Shakespeare’s plays.

-

[Rating]: 0.28

-

Person X risked their life rescuing an animal that was trapped inside a burning house

-

[Rating]:

During testing we noted that the spacing of words/lines in the prompt can affect the results given. The spacing in our prompt was thus matched to that reported by Dillion et al.1 and held constant across all completions. We also noted that ChatGPT did not always return the same result for the same prompt, even when temperature was set to 0.0. In the current project, we ran each completion once, and thus our data represent the first completion returned. We note that since the collection of our data, the text-davinci-003 model has been discontinued by OpenAI. The text-davinci-003 data reported in this paper were collected through the OpenAI API in May of 2023.

After generating moral ratings from ChatGPT (text-davinci-003) for the 60 scenarios, we pre-registered those data (see https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/6PF3X). We then collected data from a sample of human participants through CloudResearch (N = 1000). We excluded participants (n = 60) who did not complete the study, had duplicate IP addresses, or failed any of the four attention checks included in the survey (final N = 940). Participants were instructed to rate each behavior on a − 4 (Extremely unethical) to 0 (Neither unethical nor ethical) to + 4 (Extremely ethical) 9-point scale. The instructions closely followed the prompt Dillion et al. provided to ChatGPT:

-

Thank you for agreeing to participate! On the following pages, you will be presented with 60 short (1–2 sentences) scenarios.

-

Each scenario describes a behavior. We would like you to evaluate the behavior in the scenario in terms of whether the action is unethical or ethical along a scale where -4 means extremely unethical and + 4 means extremely ethical.

-

We will present each scenario to you one at a time.

-

There are no right or wrong answers. Just please read each scenario carefully, and tell us your honest opinion.

-

Click forward to begin.

Following these instructions, the 60 scenarios were presented in a random order followed, with each scenario followed by the aforementioned 9-point rating scale. Each participant responded to all 60 scenarios resulting in 56,400 human-generated morality ratings.

Following the release of GPT-4o (but after pre-registering the initial estimates from text-davinci-003), we recollected predictions from ChatGPT. Similar to our procedure for the text-davinci-003 model, we used the OpenAI API to instruct ChatGPT to rate the 60 scenarios using the GPT-4o model, which OpenAI recommends as a replacement for the discontinued text-davinci-003 model. We retained the same parameters used by Dillion et al.1. Because GPT-4o’s prompting function for completions (Chat Completions) differs from the function available in text-davinci-003 (Completions; see https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/completions), the format of the prompt for GPT-4o had to be slightly different than the prompt used for text-davinci-003. However, the training data remained identical, and we were careful to keep the prompting instructions as similar as possible to the original code used on the text-davinci-003 model (see https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/9JW23 for prompts).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study as well as the surveys, prompts for data generation, and analysis scripts are available in the files section of the OSF repository (see https:/doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/9JW23).

References

Dillon, D., Tandon, N., Gu, Y. & Gray, K. Can AI language models replace human participants?. Trends Cogn. Sci. 27, 597–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2023.04.008 (2023).

Gray, K. [@kurtjgray] We gave GPT 464 moral scenarios from past papers, and asked it to make moral judgments—they correlated .95 with human rating. X (10 May 2023). https://x.com/kurtjgray/status/1656281196916006914 (accessed 27 May 2025).

Bail, C. A. Can generative AI improve social science?. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 121, e2314021121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2314021121 (2024).

Hämäläinen, P., Tavast, M. & Kunnari, A. Evaluating large language models in generating synthetic HCI research data: A case study. In Proc. 2023 CHI Conf. Human Factors in Computing Systems (eds. Schmidt, A. et al.) Paper 433 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3580688

Anthis, J. R. et al. LLM social simulations are a promising research method. arXiv [Preprint] (2025). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.02234 (accessed 27 May 2025).

Almeida, G. F., Nunes, J. L., Engelmann, N., Wiegmann, A. & de Araújo, M. Exploring the psychology of LLMs’ moral and legal reasoning. Artif. Intell. 333, 104145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2024.104145 (2024).

Lehr, S. A., Caliskan, A., Liyanage, S. & Banaji, M. R. ChatGPT as research scientist: probing GPT’s capabilities as a research librarian, research ethicist, data generator, and data predictor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 121, e2404328121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2404328121 (2024).

Messeri, L. & Crockett, M. J. Artificial intelligence and illusions of understanding in scientific research. Nature 627, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07146-0 (2024).

Harding, J., D’Alessandro, W., Laskowski, N. G. & Long, R. AI language models cannot replace human research participants. AI Soc. 39, 2603–2605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-023-01725-x (2024).

Nie, A. et al. Moca: measuring human–language model alignment on causal and moral judgment tasks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 36, 78360–78393 (2023).

Bisbee, J., Clinton, J. D., Dorff, C., Kenkel, B. & Larson, J. M. Synthetic replacements for human survey data? The perils of large language models. Polit. Anal. 32, 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2024.5 (2024).

Gibson, A. F. & Beattie, A. More or less than human? Evaluating the role of AI-as-participant in online qualitative research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 21, 175–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2024.2311427 (2024).

Wachowiak, L., Coles, A. & Celiktutan, O. Are large language models aligned with people’s social intuitions for human–robot interactions? In 2024 IEEE/RSJ Int. Conf. Intelligent Robots and Systems 2520–2527 (IEEE, 2024). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.05701

Davani, A., Díaz, M., Baker, D. & Prabhakaran, V. Disentangling perceptions of offensiveness: Cultural and moral correlates. In Proc. 2024 ACM Conf. Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency 2007–2021 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, 2025). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2312.06861

Argyle, L. P. et al. Out of one, many: using language models to simulate human samples. Polit. Anal. 31, 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2023.2 (2023).

Abdurahman, S. et al. Perils and opportunities in using large language models in psychological research. PNAS Nexus 3, pgae245. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae245 (2024).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B Methodol. 57, 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x (1995).

Takemoto, K. The moral machine experiment on large language models. R. Soc. Open Sci. 11, 231393. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.231393 (2024).

Santurkar, S. et al. Whose opinions do language models reflect? In Proc. 40th Int. Conf. Machine Learning (eds. Krause, A. et al.) 29971–30004 (PMLR, 2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.17548

Marjieh, R., Sucholutsky, I., van Rijn, P., Jacoby, N. & Griffiths, T. L. Large language models predict human sensory judgments across six modalities. Sci. Rep. 14, 21445. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72071-1 (2024).

Clifford, S., Iyengar, V., Cabeza, R. & Sinnott-Armstrong, W. Moral foundations vignettes: a standardized stimulus database of scenarios based on moral foundations theory. Behav. Res. Methods 47, 1178–1198. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-014-0551-2 (2015).

Cook, W. & Kuhn, K. M. Off-duty deviance in the eye of the beholder: Implications of moral foundations theory in the age of social media. J. Bus. Ethics 172, 605–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04501-9 (2021).

Effron, D. A. The moral repetition effect: Bad deeds seem less unethical when repeatedly encountered. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 151, 2562–2585. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001214 (2022).

Grizzard, M., Matthews, N. L., Francemone, C. J. & Fitzgerald, K. Do audiences judge the morality of characters relativistically? How interdependence affects perceptions of characters’ temporal moral descent. Hum. Commun. Res. 47, 338–363. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqab011 (2021).

Mickelberg, A. et al. Impression formation stimuli: A corpus of behavior statements rated on morality, competence, informativeness, and believability. PLoS ONE 17, e0269393. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269393 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Kurt Gray, Yuling Gu, and Dr. Niket Tandon’s assistance in discussing their prompting procedures. The authors would also like to acknowledge Lucy Brown, Annie Dooley, and Samantha Flanagan for help in proofing study materials.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G. conceptualized the study; M.G., R.F., C.K.M., N.L.M., and C.J.F. designed the study; R.F. and M.F. wrote code to generate the AI predictions; M.G., R.F, C.K.M. and C.J.F. designed the survey; C.K.M. and M.G. pre-registered the study; M.G. collected the data; M.G., R.F., C.K.M., N.L.M., and A.L. analyzed the data and conceptualized the implications; M.G. and R.F. wrote the first draft of the paper. M.G., R.F., C.K.M., N.L.M, and A.L. revised the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grizzard, M., Frazer, R., Luttrell, A. et al. ChatGPT does not replicate human moral judgments: the importance of examining metrics beyond correlation to assess agreement. Sci Rep 15, 40965 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24700-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24700-6