Abstract

The mining cycle of multi-section stopes in steeply dipping coal seams is protracted, and the ground pressure appearance is complex.This study utilized physical simulation and theoretical analysis to investigate the surrounding rock structural evolution mechanism in multi-section longwall stopes of steeply dipping coal seams, the mechanical response of barrier pillars under the transient change excitation of the overburden spatial structure, and determine the key dimensions of barrier pillars for controlling the surrounding rock structure. These findings indicate that the movement and structural evolution of the surrounding rock in multi-section stopes of steeply dipping coal seams are governed by the stability of the barrier pillars. Transient changes in the overburden structure have been demonstrated to induce alterations in the static and dynamic mechanical responses of the barrier pillars.The instantaneous maximum abutment pressure, which is formed by the dynamic and static superimposed loads on the barrier pillar, can be calculated through the establishment of a mechanical model based on the overburden structure of the gob prior to and following the transient. By taking the instantaneous maximum abutment pressure as the static load, the critical width and yield critical width of the barrier pillar can be obtained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The term "steeply dipping coal seams" refers to coal seams with burial angles ranging from 35° to 55°, which are recognized in the mining industry as being challenging to extract1. A systematic transition from non-mechanized to mechanized mining has been achieved, encompassing the development of ground control theory and technology, advancements in coal mining methodologies and processes, and the research and development of comprehensive sets of equipment2. However, extant research and practice have mainly concentrated on the theory and technology of single-section mining of steeply dipping coal seams, while research on multi-section mining remains comparatively underdeveloped.

In the mining of steeply dipping coal seams using multi-section longwall faces, when the width of barrier pillars is small, extensive stratum movement may occur in the stope. This has the potential to result in the amalgamation of two gobs, which can in turn precipitate a range of disasters. A substantial corpus of research has been conducted by numerous scholars. This research encompasses analyses of the surrounding rock structure of barrier pillars in steeply dipping coal seams3,4,5,6, stress distribution characteristics and optimal sizing of barrier pillars7,8, multi-section working face mining methods9, and stability analysis of entry10,11,12. These studies have partially elucidated the load-bearing characteristics, deformation, and failure mechanisms of barrier pillars in steeply dipping coal seams, laying a foundation for subsequent research. However, research has primarily focused on selecting optimal pillar dimensions and analysing influencing factors. Systematic research on the evolution of surrounding rock structures in multiple stopes of steeply dipping coal seams remains scarce.

The fracture of hard key strata in multi-section stopes of steeply dipping coal seams not only causes transient changes in the surrounding rock spatial structure, but also instantaneously releases vibrations and their strain energy, affecting the stability of the surrounding rock in the stope13,14. As the key to controlling the destruction and migration of the surrounding rock and the spatial morphology of multi-section stopes, the transient effects of the overburden structure on the dynamic and static superimposed loads on the barrier pillars should be considered. However, research in this field has been limited.

This paper uses physical simulation to investigate the transient changes characteristics of the overburden in a multi-section stope of a steeply dipping coal seam, summarising the evolution mechanism of the spatial structure of the surrounding rock in such a stope. Based on dynamic theory, the paper analyses the mechanical response characteristics of barrier pillars under the transient changes excitation of the spatial structure of the overburden and calculates the combined dynamic and static loads acting on these pillars. Using the equilibrium states before and after overburden structural transients changes, the width of the barrier pillars controlling the evolution of the multi-section stope overburden structures is determined. This study is significant for refining ground control theory in the multi-section mining of steeply dipping coal seams.

Background

The mining area of the Xinjiang Coking Coal (Group) 2130 Mine extends approximately 11.5 km east–west and 0.86 km north–south, covering an area of about 9.9312 km2. The surface elevation of the area in question ranges from + 2183 m to + 2222 m, and is characterised by a high-mountain gully terrain, with no building present that might affect operations. The mine extracts Jurassic Badawan Formation coal seams that are characterised by simple monoclinal structures with generally stable occurrence. The primary 5# coal seam exhibits an inclination of 36–46°, with an average of 45°, and thicknesses ranging from 3.58 to 9.77 m, with an average thickness of 5.77 m. The coal in question has a unit weight of 1.35 tons per cubic metre and a hardness coefficient ( f ) of 0.3–0.5. The coal’s spontaneous combustion tendency grade, designated as ΔT, ranges from 9℃ to 14℃, categorised as Grade IV. The coal dust explosion index Vr, which ranges from 24 to 45%, is indicative of a medium explosion hazard level. The gas outburst rate ranges from 1.52 to 4.62 m3/t, thus classifying the mine as gas-abnormal.The coal rock characteristics of the working face of the 5# coal seam are listed in Table 1.The mechanical parameters of coal and rock are shown in Table 2.

This design illustrates the typical operating conditions for the multi-section mining of a steeply dipping coal seam. Specifically, it involves mining 5# coal seam, which has a dip angle of 45° and an average burial depth of 250 m. Seam thickness: 4 m. The adjacent longwall faces feature an inclined length of 120 m, a strike length of 2,000 m and a mining height of 4 m. Both working faces employ fully mechanised, high-height coal mining technology with a caving method for managing the gob.

Mechanism of the evolution of the structure of the surrounding rock in multi-zone stopes

Physical simulation experiment design

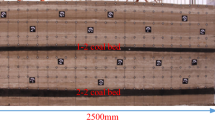

For the present experiment, a variable-angle plane similarity simulation experimental frame from the Xi’an University of Science and Technology was used. The dimensions of the experimental frame are as follows: length × width × height = 2150 × 200 × 1800 mm. In accordance with the established principles of similarity laws, According to the similarity law, the model geometric similarity constant is 150, the unit weight similarity constant is 1.5625, the stress similarity constant is 234.375, the load similarity constant is 2.27 × 106, and the time similarity constant is 12.247. Utilizing the physical and mechanical parameters of the coal rock mass, 70–140 mesh quartz sand, fly ash, gypsum, and calcium carbonate were identified as analogous materials. These materials were amalgamated in accordance with the specified ratio, to which water was added, the mixture was agitated, and the resultant blend was introduced into the model frame. The mixture was then compressed with a substantial amount of object to achieve the requisite density. Mica powder with a mesh size of 8–20 µm was selected as the material to separate the rock layers. An equivalent iron brick was placed on top of the model to act as the load from the unmodelled overburden.

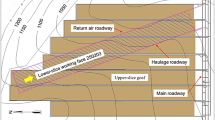

The experiment used a PENTAX R-400NX total station to monitor the displacement of the overburden, pressure sensors to monitor the abutment pressure on the floor, and a digital camera to photograph the collapse of the overburden. The displacement monitoring points were meticulously arranged along the coal seam dip on the surface of the model (with a spacing of 5 cm between points and 4 cm between rows). The arrangement of the rows corresponds to the immediate roof (row b), the main roof (row d), and the roof above the main roof (row g). This phenomenon is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Two experiments were conducted. In the initial experiment, the width of the barrier pillar was 20 cm (30 m); in the subsequent experiment, the width of the barrier pillar was 6.7 cm (10 m). In both experiments, the length of each working face was 80 cm (120 m) and the mining height was 3 cm (4 m). Initially, the upper section of the 5 coal seam # 5 was mined, followed by the lower section. Finally, the coal pillars were manually weakened to simulate their destruction owing to long-term plastic flow.

Characteristics of overburden movement evolution

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the overburden movement characteristics following mining completion in two working faces of a steeply dipping coal seam are demonstrated, in addition to the overburden movement characteristics subsequent to the destruction of barrier pillars. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the vertical displacement characteristics of the main roof and the overlying high-level roof in a multi-section stope are depicted, with shaded areas denoting sectional pillars. The experimental observations indicate the following:

1) Following the extraction of mineral resources from the upper section of the working face, the roof exhibited asymmetric deformation and fracturing, with the collapsed rock mass filling the gob unevenly. The stope thus formed an asymmetric, terraced roof damage envelope shell and an accumulation structure of collapsed rock masses. The formation of an “empty area” was observed in the upper region of the gob. During the mining process of the lower section working face, the overburden in the upper section experienced secondary displacement as a result of its influence.

2) Following the mining of the lower section working face, the characteristics of the overburden collapse and movement, as well as the surrounding rock structure, were found to be analogous to those of the upper section. However, the range of strata movement was smaller, roof collapse level was lower, and exposed length was longer, as shown in Figs. 2(b) and (d).

3) Following the collapse of the barrier pillar, the rock pillar above it tilts, thereby squeezing the gob in the lower section. This, in turn, results in an overburden on the stope moving as a whole. The gobs in the two sections were found to be interconnected, resulting in the formation of a space shell structure that spanned the two sections. The upper section exhibited a tilt towards the roof above it, resulting in a secondary fracture, and the collapsed rock pile structure also moved towards the lower side.The collapsed rock pile structure at the bottom of the lower section of the gob was more compact, and the area of the ‘air space’ at the upper was reduced. The movement of the rock pillars increased concomitantly with the decrease in the width of the barrier pillar. When the width of the barrier pillar was 10 m, the vertical displacement of the rock pillar was approximately 2.5 m; when the width of the barrier pillarr was 30 m, the vertical displacement of the rock pillar was approximately 2 m.Concurrently, the height of the new overburden shell structure in the stope increased with the decrease in the width of the barrier pillar. When the width of the barrier pillar was 30 m, the highest point of the detachment fracture was 80 m from the floor. When the width of the barrier pillar was 10 m, the highest point of the detachment fracture was 94 m from the floor.

Characteristics of distribution of inclined abutment pressure on the floor of the stope

Figure 4 shows the distribution characteristics of abutment pressure on the stope floor. The shaded areas in the figure represent unmined coal; from bottom to top: pre-mining, upper section working face mining completed, lower section working face mining completed, and barrier pillar collapse. This phenomenon indicates the following.

1) During mining of the lower section, the failure of the main roof precipitated discontinuous changes in the abutment pressure at the barrier pillar. This phenomenon is known as a ‘step change’ in the field of seismology15,16. In instances where the width of the barrier pillar was minimal, the abutment pressure exhibited a solitary peak distribution before and after the failure of the primary roof of the lower section. In instances where the width of the barrier pillar was substantial, the abutment pressure at the coal pillar exhibited an asymmetrical double peak distribution prior to the failure of the main roof, transitioning to a single peak distribution post-failure.

2) Once mining operations have been completed, but before the collapse of the barrier pillars, the load on the upper rock strata in each section is distributed and transmitted by their respective overburden structures. This results in the formation of side abutment pressure at the inclined upper and lower coal walls of the section stope and at the barrier pillars.As the width of the barrier pillar decreases, the abutment pressure at the barrier pillar increases. When the width is 30 m, the peak abutment pressure is 5.1 times the primary rock stress, and when the width is 10 m, the peak abutment pressure is 7.9 times the primary rock stress.

3) Following the collapse of the barrier pillar, the rock pillar above it also collapsed. This caused extensive movement of the overburden in the stope and significantly reduced the abutment pressure at the barrier pillar. The side abutment pressure on the upper and lower sides of the gob continued to increase as the barrier pillar’s width decreased, remaining asymmetrically distributed.

Mechanism of surrounding rock structure evolution in multi-section stopes

Integration of experimental observations with rock pressure theory analysis revealed that following mining in the upper section, the surrounding rock spatial structure of the stope conforms to the general characteristics of steeply inclined longwall faces.

As the lower section of the working face was mined, the roof movement and structure of the surrounding rock in the stope demonstrated periodic development, with each cycle comprising the following two processes, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The initial process occurred from the termination of the preceding stratum movement to the onset of key stratum fracture. During this process, the abutment pressure at the barrier pillar in the gob of the lower section changed uniformly and gradually.Secondly, the fracture of the key stratum occurred, and this continued until the end of the strata movement. This process is relatively brief, and the abutment pressure at the barrier pillar in the section affected by the fracture of the key stratum rapidly increases.

Subsequently, there were three main types of surrounding rock movement in the steeply dipping coal seam multisection stope:

(A) In instances where the width of the barrier pillar was substantial, the formation of two roof damage envelope shells within the stope became evident. The roof loads of the two sections were then transmitted to the barrier pillar through the damage envelope shell, as illustrated in Fig. 6. In this particular instance, the key stratum of the lower section can undergo periodic fracturing in an autonomous manner. However, a significant quantity of coal resources are left behind, and the stress concentration at the barrier pillar affects the mining of the lower coal seam.

(B) The width of the barrier pillar gradually decreased, and the load borne by the pillar gradually increased; however, the key stratum in the lower section could still undergo periodic fracturing independently, as shown in Fig. 6(a). In this particular instance, within the gob situated behind the working face of the lower section (illustrated by the light red and light green regions in Fig. 6(a)), the barrier pillar maintains its stability, thereby effectively isolating the working face of the lower section from the gob of the upper section.It is noteworthy that the minimum strike length of this area is equivalent to one periodic weighting interval. In the distant gob, that is, the light blue area in Fig. 6(a), the barrier pillar may be destroyed owing to the long-term plastic flow. The dip structure of the surrounding rock at this location is illustrated in Fig. 2(b). In this instance, it is conducive to the stability of the surrounding rock of the tail entry and the working face of the lower section that are inclined towards the upper coal wall, which can prevent water accumulated in the gob of the upper section from flowing into the working face of the lower section, and the remaining coal resources are reduced.

(C) In instances where the barrier pillar width is minimal, subsequent to the mining of the lower working face, the barrier pillar within the gob is the first to be destroyed. This results in the gobs of the two sections becoming interconnected, as illustrated in Fig. 6(b). In this instance, the remaining coal resources are limited. The stability of the surrounding rock and coal wall in the tailentry ahead of the working face becomes more challenging to maintain. Furthermore, the situation of water accumulation in the gob of the upper section and air leakage from the gob of the lower section to the upper section is more serious..

It can thus be concluded that the movement process and spatial structure of the surrounding rock in multi-section stopes of steeply dipping coal seams can be controlled by controlling the width of the barrier pillar.In situation A, the critical width at which the barrier pillar remains stable is BW. The distinction between situations B and C depends on their ability to break the key stratum of the lower section independently and periodically. The critical state is defined as the yield width of the barrier pillar when it is subjected to maximum load during one periodic weighting period of the working face of the lower section, which can be set as BL.If the width of the barrier pillar is greater than BW, it is situation A; if the width is greater than BL but less than BW, it is situation B; if the width of the barrier pillar is less than BL, it is situation C.

Calculation method for dynamic and static superimposed loads on barrier pillars

Mechanical response of barrier pillars under transient excitation of overburden structure

As indicated by the theories of system and structural dynamics, instantaneous changes in internal and external factors are known to induce dynamic mechanical responses in objects (structures and systems). Discrepancies inevitably emerge between the static mechanical responses of the equilibrium state prior to the transient and the equilibrium state subsequent to the transient. The term ‘internal factors’ is used to denote the mechanical properties, including the structural characteristics and material properties of objects. By contrast, ‘external factors’ refer to the mechanical environment, including the load characteristics and boundary conditions of the object17. To illustrate this point, consider the systems depicted in Fig. 7(a) and Fig. 7(b). It is evident that the concurrent effect of the external dynamic load F(t) and the instantaneous failure of the No. 2 spring damping subsystem result in a transition from a steady state to an unstable state and then back to a steady state. Owing to the difference between the two steady-state structures of the system, the static mechanical response of the system undergoes a discontinuous, step-like change. For instance, the load on springs 1 and 3 instantaneously transitions from G/3 to G/2, as illustrated in Fig. 7(d).

As demonstrated in the preceding analysis, fracturing in the key stratum of the lower section has the capacity to induce transient changes in the overburden structure of the gob, which can subsequently result in the following effects on the barrier pillar within the section.First, following the fracturing of the key stratum, the roof constrained by it breaks and moves, and the load of these roofs is no longer transferred to the coal pillar. Secondly, the internal forces (shear and bending moment) on the fracture surface of the key stratum will instantaneously vanish, thereby forming an excitation load.The residual part of the key stratum will rebound and vibrate, thereby inducing a dynamic response in the barrier pillar and forming impact stress. Third, the overburden was transformed into a double-damage envelope shell structure. The overburden load transferred to the barrier pillar underwent an instantaneous change, and the static mechanical response of the barrier pillar underwent a step change.

Taking the abutment pressure on the barrier pillar in the physical simulation as an example, as shown in Fig. 8(a). In this figure, f2 (x, y) and f1 (x, y) represent the distribution characteristics of the abutment pressure (static load) on the barrier pillar before and after the transient of the overburden structure, respectively, in kN/m2; fmax (x, y) denotes the distribution characteristic of the maximum abutment pressure (static load + dynamic load) during the transient of the overburden structure, in kN/m2.The step change in abutment pressure Δf (x, y) at any position (x, y) of the barrier pillar can be expressed as.

Given the transient change nature of the overburden structure, it can be assumed that a step load is applied instantaneously. This corresponds to a sudden load in the dynamic-static method. When a sudden load is applied to the coal body, an impact stress is formed, and the dynamic-static superimposed load fmax (x, y) shown by the red curve appears in the barrier pillar, as shown in Fig. 8. It is evident that the dynamic load in the middle of the barrier pillar is ‘positive,’ whilst the dynamic load on both sides is ‘negative.’ This is because of the unloading effect of the fracture rebound of the key stratum. As the width of the coal pillar decreases, the deflection deformation of the key stratum increases prior to the transient of the overburden structure, and subsequently to the transient of the overburden structure, the rebound-unloading effect when the key stratum breaks decreases, and the load transferred to the barrier pillar decreases. Consequently, the alteration in the dynamic load in the middle of the barrier pillar decreased as the width of the barrier pillar decreased.

Estimation method for maximum dynamic load

An accurate analysis of the impact stress requires consideration of the propagation characteristics of the stress waves within the coal body. To simplify the calculations, a rough but safe energy method can be used for estimation18. The following assumptions are made: (1) During the overburden transient change process, the barrier pillar is treated as a deformable body in order to calculate its deformation energy, deformation capacity and impact stress. The roof above the barrier pillar is considered rigid and its deformation is neglected. The collision coefficient is set to zero.(2) During the overburden transient process, energy is converted only between kinetic energy, potential energy and deformation energy, and not into other forms such as thermal, acoustic or electrical energy. (3) Simultaneous deformation is assumed throughout the barrier pillar, disregarding stress wave propagation within it; (4) The mass of the barrier pillar is neglected, as are potential energy changes due to its deformation; (5) Only the effect of normal stresses on the barrier pillar is considered, disregarding the influence of shear stresses. Assumptions (1) and (2) yield conservative calculation results, while assumption (3) accounts for the non-high-speed impact of the overlying roof on the barrier pillar during overburden transient excitation.In the positive phase change zone of the coal pillar, the height is taken as the coal seam thickness h and the bottom edge as the unit area A0 of the coal body. The mechanical model shown in Fig. 9 was established, and the impact stress on the coal body during the structural transient change process was analyzed.

As illustrated in Fig. 9, the following relationships hold: F2 (x, y) = A0∙ f2 (x, y), ΔF (x, y) = A0∙Δf (x, y), and Fd (x, y) denotes the original static load, stepwise load, and maximum impact load acting on a unit area of the coal body A0, expressed in kN. H denotes the height of the coal body under the action of F2 (x, y), measured in meters; ΔH signifies the instantaneous deformation of the coal body under the action of Fd (x, y), also measured in meters; and ΔHst represents the deformation of the coal body under the action of ΔF (x, y), once again measured in meters.

As demonstrated in Fig. 9(a), prior to the occurrence of structural transients change, the coal body was subjected to a static load F2 (x, y), with its corresponding height designated as H. In accordance with the deformation mechanism, the relationship between barrier pillar thickness h and H is as follows:

where ΔHft denotes the deformation of the coal body under the action of F2 (x, y), m, E is the elastic modulus of the coal body, kN/m2.

In the equilibrium state following the structural transient change, as illustrated in Fig. 9(c), the coal body is subject to the action of both static load F2 (x, y) and step load ΔF (x, y), resulting in the formation of a deformation increment ΔHst. In accordance with the deformation mechanism, the relationship between the step load ΔF (x, y) and deformation increment ΔHst is as follows:

During structural transients, the step load ΔF (x, y) acting on the coal body is a sudden load, and an impact load Fd (x, y) is formed, causing dynamic phenomena and forming an instantaneous maximum deformation increment ΔH, as shown in Fig. 9(b). In accordance with the deformation mechanism, the relationship between the maximum impact load Fd (x, y) and the maximum deformation increment ΔH is as follows:

The deformation of the coal body was relatively insignificant, and its self-weight was considerably lower than that of the external load. Concurrently, alterations in the gravitational potential energy of the coal body were not considered. According to the law of conservation of mechanical energy, the kinetic energy Ek and potential energy Ep of the impact object during the impact process are equal to the strain energy Ved of the coal body.

Under the action of an impact load Fd (x, y), when the deformation of the coal body is ΔH, combining Eq. (4), the potential energy Ep reduced by the impact object can be obtained as.

The initial velocity of the impact object was zero, and the final velocity when the coal body reached the maximum deformation ΔH, as shown in Fig. 9(b),was also zero. This implies that the kinetic energy of the coal body remains constant, that is, Ek = 0. At the same time, the strain energy Vft stored in the coal body before impact is.

During the impact process, when the coal body has the maximum deformation increment ΔH, the stored strain energy Vlt is.

Then, from Eqs. (7) and (8), the newly increased strain energy Ved in the coal can be expressed as.

Substituting Eqs. (2) and (4) into Eq. (9) and simplifying, we obtain.

Substituting Ek = 0, Eq. (6), and Eq. (10) into Eq. (5) and simplifying to obtain the maximum impact load Fd (x, y) as follows:

Based on Eq. (1), ΔF (x, y) is.

From Eqs. (11) and (12), the maximum impact stress fd (x, y) on the coal body can be obtained as follows:

Thus, it can be concluded that the maximum dynamic load of fd (x, y) acting on the coal body is twice the static stress gradient Δf(x, y). Therefore, the instantaneous maximum abutment pressure, fmax (x, y), acting on the barrier pillar is the sum of the critical equilibrium static load, f2 (x, y), before the transient change of the overburden structure and the maximum impact stress, fd (x, y).

Therefore, in longwall mining of steeply dipping coal seams with multiple sections, if the distribution characteristics of the abutment pressure of the barrier pillars in the lower section before and after the fracture of the key stratum are determined, the instantaneous maximum abutment pressure on the barrier pillars can be determined according to Eq. (14).

Quantitative calculation of dynamic and static loads on barrier pillars

Prior to the fracture of the key stratum in the lower section, the ‘beam arch combined beam’ structure of the overburden behind the working face is shown in Fig. 10(a). Subsequent to the fracture of the key stratum in the lower section, the ‘double arch continuous beam’ structure of the overburden behind the working face of the lower section is demonstrated in Fig. 12(a). A mechanical analysis of the two structures in question allowed for the determination of the static load on the barrier pillars of the section, both before and after the key stratum of the lower section was broken. This, in turn, allowed for the calculation of dynamic and static combined loads on the barrier pillars.

Static load on the barrier pillar before the instantaneous change in the overburden structure

In the middle of the beam arch combined beam structure, that is, at section C in Fig. 6(a), a unit width of overburden should be taken along the strike direction, and a mechanical model should be established, as shown in Fig. 10(b). Where A is fixed support, B is a single-hinged support, and BCD section is the inclined stress arc of the overburden in the upper section. The dip angle of the coal seam is α, the thickness of the coal seam is h, and the lengths of the working faces in the top and bottom sections are L1and L2. The thickness of the main roof in the lower section is A, modulus of elasticity is E, and moment of inertia is I. The widths of the plastic zones on the upper and lower coal walls of the working face in the upper section are the widths of the plastic zones on the upper and lower coal walls of the working face in the upper section are ks1 and ks2, respectively, and the widths of the plastic zones on the upper and lower coal walls of the working face in the lower section are kx1 and kx2, respectively. The width of the barrier column of the section is the width of the elastic zone k3 plus the widths of the plastic zones on both sides ks2 and kx1. Taking point B as the origin of the coordinates, we set up the coordinate system Bxy.

The overburden load is simplified as a uniformly distributed load q. The upper section of the working face collapse rock pile area was BCEXNB, and the angle of repose of the collapsed rock was β. According to its stacking and filling characteristics, its action on the BC section is assumed to be a triangular load P1(x):

In Eq. (4), PA is a constant. Let the axis equations of the BC and CD segments of the half-arch be.

The lower part of the main roof of the gob in the lower section is filled with collapsed rock masses, and the dip length of the filling area is LS. The load of the collapsed rock masses on the main roof can be simplified to a triangular distribution P2(x):

A two-span beam ABCD is a statically indeterminate structure that can be solved using the force method in structural mechanics19. The free body is shown in Fig. 11(a).

By establishing a balance equation for the BCD segment, the constraining forces FBx1 and FBy1 of AB segment on the stress arc of BCD segment and the constraining forces FDx and FDy20 at D can be calculated as follows:

Unknowns a and f can be obtained by solving Eqs. (22)-(29) simultaneously. Whese φ and c0 are the angles of internal friction and cohesion of the barrier pillars, respectively.

The stress conditions of free bodies AB are shown in Fig. 11(b). FBx1, FBy1, FBx2 and FBy2 are reaction forces. The hinge beamB is removed and replaced with redundant unknown forces X1, X2, and so on to obtain the typical equations of the force method.

X1 and X2 can be obtained using the graphical multiplication method, which is the binding force of the barrier column to overburden FBy3(X1) and FBx3(X2).

Static load on the barrier pillar after the instantaneous change in the overburden structure

In the middle of the ‘double arch continuous beam’ structure, i.e. section B in Fig. 6(a), a unit width of overburden should be taken along the strike and a mechanical model should be established as shown in Fig. 12(b). The filling characteristics of the collapsed rock blocks in the working face of the lower section of the model were analogous to those in the upper section.

By establishing the equilibrium equation, we can determine the constraining forces FD'x, FD'y, and FAx, FAy at points D’ and A, respectively. The expressions are as follows:

The restraining forces at the barrier pillars, designated Fx1 and Fy1, are as follows:

Instantaneous maximum abutment pressure of the barrier pillar

From Eqs. (14), (31), and (34), the equivalent value of the maximum instantaneous abutment pressure on the barrier pillars can be determined as follows:

Optimal Width Design for Barrier Pillars

The calculation of the strength of the barrier pillars under dynamic and static loads is significantly more complicated than that under static loads. To facilitate the calculation, the instantaneous maximum abutment pressure on the coal pillars under the combined action of dynamic and static loads can be treated as a static load for mechanical analysis. This allows the stress distribution pattern and critical width of the coal pillars to be obtained.

Mechanical model of barrier pillars in steeply dipping coal seams

When stable, the barrier pillar comprises three sections: the plastic failure zone at the top, the elastic zone in the middle, and the plastic failure zone at the bottom. The width of the pillar, designated as B, is the sum of the elastic zone width k3 and the plastic zone widths ks2 and kx1 on both sides. In the context of a critical stable state, the width of elastic zone k3 is equivalent to the width of the elastic zone of the mined-out pillar on one side21. As the width of the barrier pillar decreases, the coal pillar reaches the critical yield width in the absence of an elastic zone in the middle of the barrier pillar reaches the critical yield width22.

A model was established by taking barrier pillars of unit width along the coal seam, as shown in Fig. 13. The origin of the coordinates was designated as point O, with the x-axis aligned along the inclination of the coal seam and the y-axis oriented along the normal of the coal seam. When the barrier pillar was in the critical yielding state, the abutment pressure concentration factor was designated as K. When the barrier pillar was in a critical state of stability, the abutment pressure concentration factor was designated as K’. The average unit weight of the overburden is denoted by g’, and the depth of occurrence is denoted by H. The dip angle of the coal seam is designated as α; the thickness of the coal pillar is h = 2h’, the support resistances of the upper and lower sides of the coal pillar are Px1 and Px2, respectively, the width of the elastic zone of the coal pillar is k3; and the widths of the upper and lower plastic zones are ks2 and kx1, respectively. The calculation is limited in its scope, as it solely considers the effect of normal stress on coal pillars while disregarding the effect of tangential stress. The load on the barrier pillars is hypothesized to be the instantaneous maximum abutment pressure under the action of dynamic and static superimposed loads. To facilitate the calculation, the instantaneous maximum abutment pressure on the barrier pillar can be regarded as a static load for the mechanical analysis.

Calculation of the width of the plastic zone and elastic zone in the barrier pillar

Plastic zone width

Mechanical analysis of the plastic zone on the downward side of the barrier pillar was performed. As the coal body is squeezed out along the coal seam/bottom interface, the normal stress \(\sigma_{y}\) and shear stress \(\tau_{xy}\) at the slip surface satisfy the following basic equilibrium equation:

where c0 and \(\varphi_{0}\) denote the cohesion and angle of internal friction, respectively, at the interface between the coal seam and the top floor located at the coal seam interface.

When x = kx1, the normal stress at the interface between the elastic and plastic zones is divided into vertical and horizontal components as follows:

where \(\lambda\) is the lateral pressure coefficient of the normal stress at the interface between the elastic and plastic zones.

The expression for the stress component in the plastic zone is.

Furthermore, we obtained the width kx1 of the lower plastic zone of the barrier pillar as follows:

Similarly, the width ks1 of the plastic zone at the top of the barrier pillar is.

Elastic zone width

In the case of coal pillars with a gob on one side, the elastic zone of unit width should be taken along the dip of the coal seam to establish a mechanical model, as illustrated in Fig. 14.

Given that the mining thickness is less than the coal seam burial depth, it can be posited that \(\sigma_{y}\) is uniformly distributed and \(\sigma_{x}\) remains constant within the coal pillar along the normal direction of the coal seam. The following equation can be used to set \(\sigma_{x}\).

The expression for the stress component can be obtained is follows:

When y = 0 and z = h/2 or z = − h/2, \(\sigma_{1}\) and \(\sigma_{3}\) reached their maximum values. Assuming that \(\varepsilon_{2} = 0\), according to \({\raise0.7ex\hbox{${\varepsilon_{2} = \left[ {\sigma_{2} - \mu (\sigma_{1} + \sigma_{3} )} \right]}$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\varepsilon_{2} = \left[ {\sigma_{2} - \mu (\sigma_{1} + \sigma_{3} )} \right]} E}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$E$}}\), we can conclude that.

The hyperbolic D-P-Y criterion was adopted, and \(\sigma_{1}\) \(\sigma_{2}\) \(\sigma_{3}\) and Poisson’s ratio \(\mu = 1/2\) at coal yield were substituted into the calculation. This process yields width k3 of the elastic zone after simplification.

Maintain a stable critical width

The barrier pillar maintains a stable critical width BW, which can be expressed as BW = kx1 + k3 + ks, where kx1, k3, and ks1 are functions of the stress concentration factor K’. Therefore, the equivalent concentrated force of the external load can be calculated based on the abutment pressure-distribution characteristics.

The equivalent value of the instantaneous maximum normal abutment pressure of the barrier pillar under the combined action of the dynamic and static loads can be obtained using Eq. (37). By combining Eqs. (37) and (48) and substituting in the relevant parameters, K’ and BW can be obtained.

Yield critical width

The critical yield width BL of the barrier pillar is expressed as BL = kx1 + ks1, where kx1 and ks1 are functions of the stress concentration factor, K. The equivalent concentrated force of the external load can also be calculated based on abutment pressure distribution characteristics.

K and BLBy can be obtained by combining Eqs. (37) and (49) and substituting for the relevant parameters, K and BL can be obtained.

Example of calculation

The calculations were performed based on the specified typical operating conditions. The coal rock parameters under consideration were selected based on engineering examples and relevant existing research. The natural filling length of the gangue was designated as LS = 40m, angle of repose was 35°, and angle of internal friction was 45°. The widths of the plastic zones at the top and bottom coal walls in the upper section are designated as ks1 = 3m, while the width of the plastic zone on the lower coal wall in the lower section is denoted as kx2 = 2m. The side pressure coefficient was assigned as \(\lambda = 0.47\), the cohesion of the coal seam interface was defined as c0 = 1.8MPa, and the angle of internal friction of the coal seam interface was specified as \(\varphi_{0} = 25\). Figure 15 shows the curve of the calculated internal limit equilibrium position of the barrier pillar as a function of width.

As illustrated in the figure, the abscissa of the dashed line on the left corresponds to the yield critical width BL of the barrier pillar, BL = 7.48m, and the abscissa of the dashed line on the right corresponds to the stable critical width BW of the barrier pillar, BW = 15.29m. The area to the left of the dotted line on the left corresponds to the situation in which the entire barrier pillar is in a plastic state. The area between the two dotted lines corresponds to the situation in which the barrier pillar is in a long-term plastic flow state and is destroyed. At this time, the middle is the elastic zone and the load is large. The area to the right of the right dotted line corresponds to a situation where the width of the barrier pillar is greater than the stable critical width.

Conclusion

-

(1) The structural evolution of the surrounding rock in the multi-section stopes of steeply dipping coal seams were controlled by the barrier pillars. In the event of the width exceeding the critical width, the two gobs will invariably be isolated.If the width decreases yet remains greater than the yield critical width, the working face of the lower section becomes separated from the gob of the upper section, yet the two gobs remain connected at a distance behind the working face. When the width was less than the yield critical width, the coal pillar was destroyed as the lower section was mined.

-

(2) The fracture of the key stratum in the lower section causes transient changes in the overburden structure of the stope, which in turn causes static mechanical response changes and dynamic mechanical responses in the barrier pillar. The instantaneous maximum abutment pressure exerted on the barrier pillar is equivalent to the sum of the static load prior to the transient load and the maximum dynamic load.

-

(3) Before and after the transient changes of the overburden structure in the multi-section stope of the steeply dipping coal seam, the overburden structure behind the working face of the lower section comprises a ‘combined beam arch’ and double-arch continuous beam. These two structures can be used to establish mechanical models to calculate the instantaneous maximum abutment pressure on the barrier pillar.

-

(4) Using the equivalent value of the instantaneous maximum abutment pressure on the barrier pillar as the static load allowed us to derive expressions for the widths of the plastic and elastic zones of the coal pillar. This enabled us to obtain the critical widths for stability and yield.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Wu, Y. et al. Progress,practice and scientific issues in steeply dipping coal seams fully-mechanized mining. J. China Coal Soc. 45, 24–34 (2020).

Wu, Y. et al. Reform and prospects of mining technology for large inclined coal seam in China. Coal Sci. Technol. 52, 25–51 (2024).

Tu, H. et al. Instability of a coal pillar section located at a steep mining face: Pillar size selection. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 42, 6–12 (2013).

Men, J. et al. Study on Overburden Strata Structure Features and Stress Distribution Law of Coal Pillar in Inclined Seam. Coal Sci. Technol. 42, 21–24 (2014).

Qu, X. et al. Research on mechanism of rock burst induced by coal pillar failure in mine goaf. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 34, 1134–1140 (2017).

Zheng, Z. et al. Study on reasonable coal-pillar width and surrounding-rock control of 751 gob-side irregular roadway in inclined seam. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 36, 223–231 (2019).

Wei, F., Chen, J. & Zou, Y. Influence factors and change law of protection coal pillars left. Coal Sci. Technol. 36, 85–87 (2006).

Li, X., Li, H. & Yuan, R. Stress distribution influence on segment coal pillar at different dip angles of working face. J. China Coal Soc. 37, 1270–1274 (2012).

Li, J., Qu, Z. & Sun, Q. Multi sectional coalm ining method applied to deep inclined thin seam and medium thick seam. Coal Sci. Technol. 33, 11–13 (2005).

Deng, Y. & Wang, S. Feasibility analysis of gob-side entry retaining on a working face in a steep coal seam. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 24, 499–503 (2014).

Zhang, Y., Tang, J., Chen, Y. & Li, G. (2017) The characteristics and application of flexible support technique for a 755 roadway in deeply inclined coal seam. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 34, 542-548 555 (2017).

Zhang, L., Zhao, J. & Wang, S. Research on the roof structure evolution and control technology of 753 gob-side entry retaining with cutting the roof in steeply dipping seam. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 5, 169–178 (2020).

Wang, P., Jiang, F., Feng, Z. & Wang, D. Relationship between fracture of high-position thick and hard roof and mine quake forecast. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 33, 618–623 (2011).

Zhou, N., Li, Z., Zhang, J., Li, B. & Wang, H. Energy evolution and backfilling weakening mechanism of hard rock strata 757 causing dynamic disasters in coal mining district. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 40, 078–1091 (2023).

Qiu, Z. & Shi, Y. Observation example of remote stress step change caused by earth-quake. Sci. Sinica (Terrae) 33, 60–64 (2003).

Yue, C. et al. Discussion on the relationship between the co-seismic stress field and the 748 distribution coseismic step among deformation observation stations from the Maduo MS7.4 earthquak. Earthq. Res. China. 38, 189–198 (2022).

He, M., Xie, H., Peng, S. & Jiang, Y. Study on rock mechanics in deep mining engineering. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 24, 2803–2813 (2005).

Sun, X., Fang, X. & Guan, T. Mechanics of Marerials (II) (Higher Education Press, 2016).

Long, Y., Bao, S. & Kuang, W. Structural mechanics tuto-rial(I) (Higher Education Press, 2000).

Luo, S., Wu, Y., Liu, K., Xie, P. & Lang, D. Study on the shape of the space stress arch shell in steeply dipping coal seam mining. J. China Coal Soc. 41, 2993–2998 (2016).

Qian, M., Shi, P. & Xu, J. Control pressure and strata control (University of Mining and Technology press, 2010).

Xu, Z. Elasticity (Higher Education Press, 2016).

Funding

This study was supported by the Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China.(Grant number: 51634007,52274139,51974227).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yongping Wu: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding acquisition, Review & Editing. Jingyu Huangfu: Writing-original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation of data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization. Shenghu Luo: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Review & Editing. Yepeng Tang: Validation of data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization. Zhuangzhuang Yan: Validation of data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization. Chengyang Tian: Formal analysis, Visualization. Tong Wang: Validation of data curation and Formal analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Huangfu, J., Luo, S. et al. Control mechanism of the surrounding rock structure of multisection stopes in steeply dipping coal seams under overburden transient changes excitation. Sci Rep 15, 40955 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24723-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24723-z