Abstract

Wolbachia, a bacterial endosymbiont, acts as an obligate nutritional mutualist in the bed bug, Cimex lectularius. Wolbachia in C. lectularius (wCle) supplements B-vitamins, namely riboflavin (B2) and biotin (B7), which are deficient in the bed bug’s diet of vertebrate blood. Experimental elimination of wCle significantly impairs fitness in bed bugs, resulting in slow development, low egg production and egg hatch rate, and smaller adult body size. Although this obligatory symbiosis has been well-documented, the specific physiological mechanisms by which wCle-supplemented B-vitamins promote bed bug fitness remain unclear. We hypothesized that B-vitamin deficiency impairs digestion in aposymbiotic bed bugs, and in this study we investigated the effects of wCle elimination on three digestive processes in the bed bug – diuresis, erythrocyte (red blood cell) lysis, and protein catabolism. Our results show that wCle elimination significantly slows both diuresis and protein catabolism. We also demonstrate that riboflavin is critical for the breakdown of hemoglobin, the main protein component of red blood cells, but not albumin, the main protein component of plasma. We propose that the lack of wCle-supplemented riboflavin results in systemic protein deficiency, driving various fitness-related deficits in aposymbiotic bed bugs. These findings enhance our understanding of bed bug digestive physiology and the wCle-bed bug nutritional mutualism, with broader implications for other blood-feeding arthropods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obligate blood feeding insects, such as lice, bed bugs, kissing bugs, tsetse flies, and louse flies, rely on vertebrate blood as their sole source of dietary nutrients. However, this specialized diet presents many challenges that insects must overcome to efficiently acquire nutrients from blood. Vertebrate blood is disproportionately high in protein, the breakdown of which produces cytotoxic byproducts that are harmful to insects1,2. Blood is also severely deficient in essential micronutrients, particularly B-vitamins, which are vital cofactors in numerous enzymatic processes. Most insects cannot synthesize B-vitamins de novo, so B-vitamin deficiency is a critical barrier to insect survival and reproduction3. To mitigate this, obligate blood feeders have evolved mutualistic associations with bacterial symbionts that supplement their diet with B-vitamins, effectively compensating for the nutritional deficits of blood4.

The common bed bug, Cimex lectularius, has evolved an obligate nutritional mutualism with Wolbachia (wCle), a bacterial endosymbiont5,6. wCle is found ubiquitously in bed bug populations worldwide, underscoring its vital role in bed bug biology7,8,9,10. Wolbachia primarily resides within a specialized gonad-associated bacteriome and is vertically inherited from females to offspring6. The elimination or reduction of wCle with antibiotic treatment significantly impairs nymphal development, lowers egg production and egg hatch rate, and results in low adult body size, underscoring its critical contribution to bed bug fitness5,6. These fitness deficits can be recovered by supplementing wCle-free bed bugs with B-vitamins, supporting that the symbiosis is driven by vitamin provisioning. wCle possesses the complete biosynthetic pathways for the production of riboflavin (vitamin B2) and biotin (vitamin B7), and partial pathways for thiamine (vitamin B1), pyridoxine (vitamin B6), and folic acid (vitamin B9), although it has only been confirmed to provide biotin and riboflavin to the bed bug11.

Our preliminary observations revealed that wCle-free bed bugs may retain blood in their gut for longer periods than wCle-present individuals (Fig. 1), suggesting a potential role for wCle in blood digestion. This prolonged retention of blood may result from disruptions in one or more of three key digestive processes: diuresis, erythrocyte (red blood cell) lysis, and protein catabolism. Drawing from previous studies in bed bugs, closely related triatomines (kissing bugs), and other hematophagous arthropods, we drafted an illustrative hypothetical timeline for these digestive events in bed bugs, illustrated in Fig. 2, to guide our investigation of these three processes.

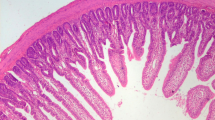

Photographs showing our preliminary observations that wCle-free bed bugs appear to retain the blood meal longer than wCle-present bed bugs, suggesting impaired digestion. Adult male bed bugs 2 weeks post adult emergence and 5 d post-feeding. (A) wCle-present and (B) wCle-free bed bugs. The white V-shaped structures that partly obscure the midgut in (A) are the paired seminal vesicles.

An illustrative hypothetical model for the time-course of blood digestion in Cimex lectularius. The blood meal enters the anterior midgut (AMG), where diuresis and erythrocyte lysis occur rapidly after ingestion. Protein catabolism, represented by the breakdown of hemoglobin into peptides and amino acids, is a more protracted process that primarily occurs in the middle midgut (MMG) and posterior midgut (PMG). A schematic of the bed bug gut is illustrated for reference, also including the esophagus (ES), Malpighian tubules (MT), and hindgut (HG). Created in BioRender.

Blood is primarily composed of water by volume, so blood feeding arthropods must rapidly eliminate excess fluid from their blood meal. Diuresis allows blood feeding arthropods to concentrate erythrocytes and soluble nutrients for digestion12,13. This process involves the transport of water from the midgut into the hemolymph, processing by the Malpighian tubules, and subsequent elimination via the hindgut14. Diuresis is a rapid process, beginning during feeding (pre-diuresis) and reaching its peak within the first 4 h after a blood meal15,16. Another early post-feeding rapid process is erythrocyte lysis, which provides access to intracellular nutrients and is typically completed within 48 h of ingesting a blood meal17. Protein digestion occurs more gradually; in triatomines, digestive protease expression peaks 5 days after feeding and remains active for up to 20 days18. Although the precise timeline of blood meal digestion has not been characterized in bed bugs, they will typically feed again within 3–5 days (temperature dependent) and return to their unfed state about one week after feeding19,20,21,22. These three digestive processes are spatially compartmentalized in the gut, with erythrocyte lysis and the initial stages of diuresis occurring in the anterior midgut (AMG), where undigested blood is stored, and protein digestion occurring in the middle midgut (MMG) and posterior midgut (PMG) where digestive enzymes are produced (Fig. 2)18,23,24,25,26.

In this study, we provide the first direct physiological link between Wolbachia and digestion in bed bugs. We hypothesized that wCle-free bed bugs would exhibit delayed digestion due to B-vitamin deficiencies, particularly biotin and riboflavin. Hemoglobin, the primary protein component of erythrocytes, and albumin, the primary protein component of plasma, served as markers for protein catabolism in this study. Overall, our study offers new insights into how bacterial symbionts and B-vitamins can shape the digestive physiology of hematophagous arthropods. This study also furthers our understanding of Wolbachia-insect mutualisms, which have been reported across several groups in the Insecta27.

Results

Wolbachia elimination slows diuresis, independent of B-vitamin supplementation

There was no significant difference in the pre-feeding weights between wCle-present males (n = 18, mean ± SEM: 3.17 ± 0.086 mg) and wCle-free males (n = 18, 3.36 ± 0.088 mg) (t-test, t = 1.597, P = 0.1194). Moreover, there was no significant difference in the post-feeding weights between wCle-present males (n = 15, 8.40 ± 0.256 mg) and wCle-free males (n = 11, 8.37 ± 0.299 mg) (t-test, t = 0.07661, P = 0.9396). Nevertheless, because our approach to assessing diuresis involved repeated weighing of individual bed bugs, we normalized all subsequent body mass measures of each bed bug to its body mass immediately after blood feeding (0 h); this procedure minimized inter-individual variation. The non-normalized data are shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S1. Elimination of wCle significantly impaired the rate of diuresis in bed bugs. Within the first 4 h after they fed to repletion, wCle-free bed bugs lost mass at a significantly slower rate than the wCle-present bed bugs, and this difference persisted for 24 h post-feeding (Fig. 3A). These data suggest that slow diuresis contributes to the long-term fluid retention observed in wCle-free bed bugs. Supplementation with a B-vitamin cocktail failed to restore diuresis rates in wCle-free bed bugs at 2 h post-feeding (Fig. 3B), so the slower rate of diuresis cannot be attributed directly to B-vitamin deficiency.

Weight loss due to diuresis in wCle-present (+wCle) and wCle-free (–wCle) bed bugs with and without vitamin supplementation. (A) Bed bugs fed blood without supplemented vitamins. Each repeated body mass measure of each individual wCle-free (n = 11) and wCle-present bed bug (n = 13–15) was normalized to the body mass of that individual immediately after blood feeding (0 h). The body mass of wCle-free bed bugs was significantly higher than that of wCle-present bed bugs at 1, 2, 3, and 24 h post-feeding (asterisk, Wilcoxon test, P < 0.001). There was a significantly slower rate of diuresis in wCle-free (n = 11) bed bugs over 24 h compared to wCle-present (n = 13) bed bugs (Friedman test, P < 0.0001). (B) Vitamin rescue experiment showing changes in body mass 2 h post-feeding in wCle-present bed bugs with no vitamin supplementation, wCle-free bed bugs with no vitamin supplementation, and wCle-free bed bugs supplemented with B-vitamins (rescue). The 2 h post-feeding body mass was normalized to the respective body mass of the same individual immediately after blood-feeding (0 h). Treatments that do not share lowercase letters are significantly different (Wilcoxon pairwise test with multiple comparisons and Bonferroni correction, P < 0.017). Summary data are shown as box plots and sample sizes are shown in parenthesis. Non-parametric tests were used because these data were not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test).

Wolbachia elimination slows erythrocyte Lysis within 20 h of a blood meal

There was a significant increase in the erythrocyte concentration within the first 4 h post-feeding in both wCle-present and wCle-free bed bugs, likely attributed to diuresis (Supplementary Information Fig. S2). Therefore, the erythrocyte concentration data between 8 and 48 h post-feeding was normalized to the mean erythrocyte concentration of the respective group at 4 h post-feeding. This approach was necessary because erythrocyte counting was destructive, precluding repeated assays of the same individuals over time. The non-normalized data are shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S2. After normalization, we found that erythrocyte lysis proceeded more rapidly in wCle-present than in wCle-free bed bugs, with significant differences up to 20 h post-feeding (Fig. 4). However, erythrocytes became undetectable (< 250 cells µl− 1) in both groups by 24–36 h, indicating that, while wCle elimination results in slower erythrocyte lysis, this effect is transient and unlikely to explain long-term (beyond 24 h post-feeding) differences in blood meal processing between wCle-present and wCle-free bed bugs.

Time-course of erythrocyte lysis in the midgut of wCle-present (+wCle) and wCle-free (–wCle) bed bugs after blood-feeding. Because erythrocyte concentrations rose between 0 h (immediately after blood feeding) and 4 h post feeding due to diuresis, and these were destructive measures, each erythrocyte concentration at 8–36 h was normalized to the mean erythrocyte concentration of the respective treatment group at 4 h post-feeding. wCle-free bed bugs had higher proportions of erythrocytes in their midguts between 8 and 20 h post-feeding (Wilcoxon test, P < 0.05). Statistical testing could not be conducted at 36 h because erythrocyte concentrations were too low to count with a hemocytometer. Summary data are shown as box plots and sample sizes are shown in parenthesis. Non-parametric tests were used because these data were not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test).

Wolbachia elimination impairs hemoglobin and albumin digestion

Immediately after blood feeding, wCle-free and wCle-present bed bugs had similar levels of both hemoglobin and albumin, respectively (Fig. 5A, B), indicating that both groups ingested similar volumes of blood. Hemoglobin digestion was significantly slower in wCle-free bed bugs, with only a 31% reduction in mean hemoglobin content within 8 days of a blood meal, compared to a 61% reduction in wCle-present bugs (Fig. 5A). In both groups, there was a linear decline in hemoglobin content, but the slope in wCle-present bed bugs was significantly steeper, demonstrating a much faster rate of digestion than wCle-free bed bugs. Albumin digestion followed a non-linear pattern, with wCle-present bed bugs still exhibiting a faster rate of digestion (Fig. 5B). The total amount of albumin digested over an 8-d period was significantly lower in wCle-free bed bugs. Overall, these findings suggest that wCle is necessary for bed bugs to efficiently break down major blood proteins. However, it appears that the elimination of Wolbachia impairs hemoglobin digestion to a greater extent than albumin digestion.

Digestion of hemoglobin and albumin in bed bug midguts within 8-d of blood-feeding. (A) Hemoglobin digestion. Midguts were dissected from groups of wCle-present (+wCle) and wCle-free (–wCle) bed bugs at 2-d intervals immediately after blood-feeding (0-d) and up to 8-d later. Each data point represents the measured hemoglobin amount (µg) in an individual bed bug midgut. Hemoglobin digestion in wCle-free bed bugs was significantly slower than in wCle-present bugs over the 8-d period (one-way ANCOVA, F = 18.79, df = 3,78, P < 0.0001). The final hemoglobin content at 8-d post-feeding was significantly higher in wCle-free bed bugs (Welch’s t-test, t = 5.028, df = 6.16, P = 0.0022). (B) Albumin digestion. Aliquots of the same midgut samples from hemoglobin assays were used for albumin assays. Each data point represents the measured albumin amount in an individual bed bug midgut. There was a significant difference in the rate of albumin digestion between wCle-present and wCle-free bed bugs within 8-d of blood-feeding, evidenced by the non-overlapping confidence intervals after 0-d post feeding and a one-way ANCOVA on log-transformed data (one-way ANCOVA, F = 59.08, df = 4,76, P < 0.0001). The albumin content was significantly higher in wCle-free bed bugs 8-d post-feeding (Welch’s t-test, t = 6.09, df = 6.02, P = 0.0009). Red and gray 95% CIs are shown for wCle-present and wCle-free, respectively. Sample sizes at each time point are reported above the X-axis as (n = wCle-present, n = wCle-free).

Riboflavin rescues hemoglobin digestion, but not albumin digestion in wCle-free bed Bugs

To determine whether vitamin supplementation could recover impaired protein digestion in wCle-free bed bugs, we tested five B-vitamin treatments: (1) no vitamins, (2) full vitamin mix consisting of B2, B7, B1, B6, and B9 (3) B2 only, (4) B7 only, and (5) B1, B6 and B9 mix. Because we detected differences in the initial levels of both hemoglobin and albumin in wCle-free bed bugs fed various B-vitamins, the individual data points at 4- and 8-days post feeding were normalized to the mean of the respective treatment immediately after feeding (0-d post feeding) (Figs. 6 and 7). The non-normalized data are shown in Supplementary Information Figs. S3 and S4.

Rescue experiment of hemoglobin digestion in wCle-free bed bugs treated with B-vitamins. wCle-free bed bugs were assayed 4-d and 8-d post-feeding. Ten bed bug midguts were dissected for each treatment and time point. Within each treatment group, each hemoglobin measurement at 4-d and 8-d was normalized to mean hemoglobin content of the respective treatment group immediately after feeding (0-d post-feeding). There was a significant difference between treatments at both time points post-feeding (one-way ANOVA, d 4: F = 14.73, df = 4,45, P < 0.0001; d 8: F = 16.99, df = 4,45, P < 0.0001). Treatments within each time point that do not share lowercase letters are significantly different from each other (Tukey’s HSD test, P < 0.05). For reference to wCle-present bed bugs, the two horizontal red lines represent the average proportion of the initial hemoglobin content for wCle-present bed bugs from 4-d and 8-d respectively in the experiment shown in Fig. 5A. Both riboflavin and the full vitamin mix (B2, B7, B1, B6, and B9) resulted in significant recoveries of hemoglobin digestion compared with the no-vitamin controls at both 4- and 8-d post-feeding. Means ± SEM are shown.

Rescue experiment of albumin digestion in wCle-free bed bugs treated with B-vitamins. wCle-free bed bugs were assayed 4-d and 8-d post-feeding. Aliquots of the same midgut samples from hemoglobin assays (Fig. 6) were used for albumin assays. Within each treatment group, each albumin measurement at 4-d and 8-d was normalized to mean albumin content of the respective treatment group immediately after feeding (0-d post-feeding). There was a significant difference between treatments at both time points post-feeding (n = 10 per treatment, one-way ANOVA, d 4: F = 10.71, df = 4,45, P < 0.0001; d 8: F = 10.041, df = 4,45, P < 0.0001). Treatments within each time point that do not share lowercase letters are significantly different from each other (Tukey’s HSD test, P < 0.05). The full vitamin mix contained B2, B7, B1, B6, and B9. There was a significant recovery of albumin digestion with riboflavin treatment at 8-d post-feeding compared to the no-vitamin controls. For reference to wCle-present bed bugs, the two horizontal red lines represent the average proportion of the initial albumin content for wCle-present bed bugs from 4-d and 8-d respectively in the experiment shown in Fig. 5B. Means ± SEM are shown.

Only riboflavin (B2), either alone or in combination with other B-vitamins, fully restored hemoglobin digestion in wCle-free bed bugs at both 4 and 8-d post-feeding (Fig. 6A, B). A mixture of B1, B6, and B9 provided a short-term recovery at 4-d, but was ineffective by 8-d post-feeding. In contrast, none of the B-vitamin treatments substantially improved albumin digestion in wCle-free bed bugs (Fig. 7). Notably, biotin (B7) supplementation significantly interfered with albumin digestion relative to the control (Fig. 7A). Although riboflavin slightly improved albumin digestion at 8-d post-feeding, albumin levels remained well above those observed in wCle-present bed bugs over the same time period. These results indicate a specific and critical role for wCle-provisioned riboflavin in hemoglobin digestion. In the case of albumin digestion, additional, non-B-vitamin-mediated mechanisms may be involved in this process.

Discussion

Wolbachia is the most widespread endosymbiont across the Insecta, with an estimated 60% of all insect species infected by the bacterium28. Wolbachia is perhaps best known for reproductive manipulation, enhancing its prevalence in insect populations through mechanisms such as cytoplastic incompatibility29. However, as studies of Wolbachia have extended across diverse insect lineages, it has become clear that Wolbachia plays many different roles along the spectrum of symbiosis – acting as both a parasite and mutualist. Although obligate mutualisms between insects and Wolbachia are relatively rare, facultative associations with Wolbachia are common, and can result in fitness benefits27. Even among “parasitic” Wolbachia strains, riboflavin provisioning is a common benefit reaped by insect hosts30,31. In this study, we explored the obligate dependency of bed bugs on their Wolbachia endosymbiont, namely the critical roles that Wolbachia plays in blood digestion by its host.

Wolbachia elimination impairs diuresis, erythrocyte lysis, and blood protein digestion

Our findings demonstrate that wCle-free bed bugs exhibit a markedly slower rate of blood meal digestion, driven by multiple physiological impairments. Diuresis, an early process in blood digestion, was significantly delayed in wCle-free individuals, and this deficit persisted up to 24 h post-feeding. These observations suggest that the elimination of Wolbachia leads to fluid retention which, in turn, hampers the bed bug’s ability to efficiently concentrate and process the nutritive components of a blood meal.

Although erythrocyte lysis occurred at a slightly slower rate in wCle-free bed bugs, all detectable red blood cells were lysed within 36 h of feeding in both wCle-present and wCle-free groups. This timeline is consistent with previous observations where erythrocyte concentrations decreased to near undetectable levels within 24–48 h after a blood meal17. This suggests that differential erythrocyte lysis contributes minimally to the overall delay in blood digestion in wCle-free bed bugs. Consequently, we decided not to pursue the effects of B-vitamin supplementation on erythrocyte lysis.

More critically, blood protein digestion was significantly slowed in wCle-free bed bugs. Hemoglobin and albumin represent the primary protein components of red blood cells and plasma, respectively, so inefficient digestion could potentially lead to severe protein deficiency in wCle-free bed bugs. Protein deficiency may partially underlie the notable fitness defects associated with wCle-elimination, including slow nymphal development and lower fecundity, as previously reported5,6. Retention of blood meal components from impaired digestion may also discourage frequent feedings, which would also affect fitness parameters, as female bed bugs require frequent blood meals to maximize egg production32. Finally, the delay in hemoglobin digestion may impair heme detoxification mechanisms, resulting in fitness deficits from long-term oxidative stress2.

Wolbachia-supplemented riboflavin plays a critical role in hemoglobin digestion

In most organisms, B-vitamins primarily function as cofactors (or their precursors) in diverse enzymatic reactions. Biotin and riboflavin are the only B-vitamins for which wCle possesses the full biosynthetic pathway, and these were hypothesized to compensate for processes disrupted by wCle elimination in bed bugs11. Riboflavin and biotin provisioning are common in the bacterial symbionts of obligate blood feeding arthropods, so it seemed likely that one, or both, of these vitamins would have a role in blood meal processing4,33. In contrast, wCle lacks complete pathways for thiamine (B1), pyridoxine (B6), and folic acid (B9) and is not thought to provision these vitamins to its host11. Nonetheless, we included thiamine, pyridoxine, and folic acid in our experiments because of the possibility of metabolic collaboration between wCle and the bed bug host or other microbes.

Contrary to our expectations, only riboflavin, and not biotin, fully restored hemoglobin digestion in wCle-free bed bugs. Additionally, a partial recovery was observed during the first 4-d post-feeding with the supplementation of a thiamine, pyridoxine, and folic acid mixture, suggesting a potential role for one or more of these vitamins in early stages of hemoglobin digestion. These findings demonstrate that wCle-provisioned riboflavin is essential for effective hemoglobin digestion in bed bugs. Riboflavin is a precursor to flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and flavin mononucleotide (FMN), while biotin directly serves as a cofactor for a range of carboxylase enzymes34. We hypothesize that the action of riboflavin in bed bug digestion is through its role as a precursor of FAD or FMN. However, the precise mechanism by which FAD or FMN influence hemoglobin digestion is elusive, as these cofactors are involved in a wide repertoire of metabolic pathways. While it is possible that FAD or FMN serves as a cofactor for a particular enzyme in the hemoglobin degradation pathway, it is also conceivable that riboflavin deficiency impairs an upstream pathway necessary for proper gut development or gene expression, as has been observed in some vertebrates35,36. Moreover, riboflavin supports the synthesis and activation of the B-vitamins pyridoxine and folic acid37. Future studies should investigate synergistic effects of riboflavin in combination with thiamine, pyridoxine, and folic acid to fully elucidate its role in bed bug digestive physiology.

Wolbachia-supplemented B-vitamins do not play a key role in diuresis or albumin digestion

The loss of a bacterial symbiont has been shown to slow diuresis in the obligate blood feeding triatomine, Rhodnius prolixus, and B-vitamin supplementation was sufficient to restore the function in this insect at 24 h post feeding38. However, supplementation with B-vitamins did not fully restore diuresis or albumin digestion in wCle-free bed bugs. This contrast suggests that the role of nutritional mutualists in digestion may vary across blood-feeding insect species. We propose that the observed slowing of diuresis and albumin digestion in wCle-free bed bugs may stem from a general depression of metabolic processes from protein deficiency. This lineage of wCle-free bed bugs has been propagated without wCle for over three years in our laboratory. Chronically insufficient hemoglobin digestion due to B-vitamin deficiency may induce a starvation-like state, which is known to reduce the metabolic rate39. In support of this idea, we have observed that wCle-free bed bugs have reduced locomotor activity, making them easier to catch during collection from colony jars. Thus, we hypothesize that slow hemoglobin digestion may be one of the factors driving the physiological deficits observed in wCle-free bed bugs. However, additional studies are needed to empirically determine the level of protein deficiency in wCle-free bed bugs, as it is not clear to what extent other blood proteins, like albumin, can compensate for this deficiency.

Limitations and constraints of the study

This study has several limitations. First, all experiments were conducted using only male bed bugs. This was based on the assumption that digestive processes are similar between the sexes. However, since female bed bugs consume larger blood meals than males40, the dynamics (e.g., time-course) of digestion or the impact of B-vitamin supplementation may differ between the sexes. Second, like previous studies5,6,11, we delivered B-vitamins through the blood meal. This mimics the intake of vitamins in many animals, including humans, that are dependent on dietary B-vitamins and feed frequently on relatively small meals. Bed bugs however, feed infrequently, ingesting exceptionally large blood meals. Therefore, this method of B-vitamin supplementation through blood introduced high concentrations of B-vitamins into the anterior midgut. This delivery method contrasts with what we presume is continuous B-vitamin supply provided by Wolbachia, which resides in a specialized gonad-associated bacteriome. Wolbachia increases in abundance following a blood meal41 and presumably delivers the water-soluble B-vitamins directly into the hemolymph. This difference may partly explain two of our findings; (1) that biotin treatment inhibited albumin digestion and (2) that some B-vitamin treatments caused a significant increase in midgut hemoglobin in wCle-free bed bugs. Given that biotin can bind albumin42, the high concentrations of biotin in the midgut might have interfered with enzymatic processing of albumin. With regard to hemoglobin, we suspect that some of our B-vitamin treatments may have accelerated the movement of water from the midgut into the hemocoel, increasing the concentration of red blood cells (and hemoglobin) in the midgut. Future research should examine the time-course and localization of Wolbachia-provisioned B-vitamins and explore sex-specific differences in blood digestion. Lastly, since wCle-free bed bugs may exhibit a starvation-like state with reduced metabolic activity, it is difficult to separate the specific effects of B-vitamins from broader physiological changes. Future studies should assess the effect of Wolbachia-elimination on the metabolic rate of the bed bug and specific enzymes which may be linked to digestive insufficiency.

Outstanding questions

This study raises several important questions regarding the nutritional mutualism between bed bugs and Wolbachia and the roles of B-vitamins in the digestive physiology of blood-feeding arthropods. A key finding from our study – that a single blood meal supplemented with riboflavin can fully restore hemoglobin digestion in wCle-free bed bugs – is especially noteworthy. Future research should investigate the effects of individual B-vitamins on bed bug-specific enzymes through in vitro enzyme activity assays. This could uncover specific contributions of B-vitamins to blood digestion, broadening our understanding of bed bugs and other blood-feeding arthropods. This study also provides insights into the mechanistic role of Wolbachia in enhancing host fitness and offers a valuable foundation for more comprehensive investigations into nutritional mutualisms. The potential role of Wolbachia-supplemented riboflavin in digestive physiology of the bed bug introduces new questions regarding the nature of insect-Wolbachia associations. Finally, the potential roles of other endosymbionts and gut microbes in bed bug nutrition warrant detailed studies. The microbiome of C. lectularius is sparse and dominated by Wolbachia. However, previous studies have identified a secondary endosymbiont, Pectobacterium sp., along with a limited community of gut microbes8,9. It is plausible that Pectobacterium or other members of the gut microbiota contribute to B-vitamin biosynthesis or blood digestion. Potential interactions and cooperative functions between wCle and these microbial partners should be further explored.

Materials and methods

Insect colony maintenance

The C. lectularius used in this study was the Harold Harlan strain, also known as the Ft. Dix strain, originally collected at Fort Dix, New Jersey (USA) in 1973. This strain was maintained on a human host until December 2008, after which it was transitioned to an artificial feeder and defibrinated rabbit blood until July 2021, and finally to reconstituted human blood. In 2020, we generated a wCle-free lineage of the Harlan strain by treating bed bugs with rifampicin to eliminate wCle endosymbionts and then discontinued the use of the antibiotic5. This colony has remained wCle-free for many generations, as confirmed by digital droplet PCR43. By eliminating antibiotics as a confounding factor, we ensured that any observed effects in the wCle-free bed bugs could be attributed specifically to the absence of wCle rather than to antibiotic-related interference, including pharmacological side effects that can negatively impact physiological processes44,45.

In this study, bed bugs with their wCle endosymbionts are referred to as wCle-present (also +wCle), while aposymbiotic bed bugs are termed wCle-free (also –wCle). Unless otherwise stated, all bed bugs were maintained in 20 ml vials containing file folder paper as a substrate for sheltering and egg laying and capped with plankton netting that allowed air exchange and enabled feeding. Rearing conditions were consistent across experiments, with a temperature of 27 ± 0.5 °C, 35–45% relative humidity (RH), and a 12 h:12 h light: dark cycle. Colonies and experimental insects were fed reconstituted human blood (obtained from the American Red Cross under IRB #00000288 and protocol #2018-026) using an artificial feeding system, as previously described46. To prevent erythrocyte settling, we agitated the blood with a pipette every 5 min during feeding. In all experiments, the blood was supplemented with 1 mM ATP to stimulate feeding47, and the hematocrit of the blood was set to 40% using a microhematocrit centrifuge (XC-3012, C&A Scientific, Sterling, VA), well within the normal human range of 35–50%48. For colony maintenance, the wCle-free bed bugs received B-vitamin supplementation using the Kao and Michayluk (K&M) vitamin mix49 (Millipore Sigma, Cat#K3129), while the wCle-present bed bugs were not given any additional vitamins5,41. For dissections or insect homogenization, insects were anesthetized on ice for approximately 10 min.

B-vitamin solutions

Although the K&M vitamin mix was used for colony maintenance, for all recovery experiments involving the supplementation of B-vitamins to wCle-free bed bugs, we used vitamins in concentrations consistent with the Lake and Friend (L&F) vitamin mix50. Both the K&M and L&F vitamin mixes have been shown to recover nymphal development and reproduction when added to the blood meal of wCle-free bed bugs5,6. However, the L&F mix contains higher concentrations of B-vitamins, and in preliminary experiments, we observed that bed bugs fed this mix recovered blood digestion more effectively than on the K&M mix. Combinations of only five B-vitamins (all from ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) – riboflavin (A14545), biotin (230095000), thiamine (148990100), pyridoxine (A12041), and folic acid (J62937) – were used for recovery experiments because these are the only B-vitamins which have complete or partial biosynthetic pathways within the genome of wCle11. Vitamin treatments used in recovery experiments are shown in Table 1. For colony maintenance and recovery experiments, 10 µl of a 100X vitamin stock solution was added to each 1 ml of blood just before feeding.

Diuresis assays

After feeding colonies of wCle-present and wCle-free bed bugs using the colony rearing practices described above, we selected replete (fully engorged) 5th instar bed bugs and placed them in separate 5.5 cm D × 4.8 cm H jars. Ten d later (3–5 d after adult emergence), we selected newly emerged males within a body mass range of 2.5–4.5 mg to minimize variability associated with blood meal size. There was no significant difference in the pre-feeding weights between wCle-present and wCle-free cohorts. These bed bugs were fed blood without B-vitamin supplementation and immediately weighed on an analytical balance. Bed bugs that fed to repletion were transferred individually into 7 ml glass vials containing file folder paper for sheltering. Vials were placed in an incubator at 27 ± 0.5 °C and 35–45% RH, and each bed bug was re-weighed hourly until 4 h post-feeding, and again at 24 h. To reduce the effect of variation in blood meal size in our analysis, we normalized the body mass measurements of each individual bed bug as proportions of the same individual’s body mass immediately after feeding (time 0) (Fig. 3). The non-normalized data are shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S1. To evaluate the effects of B-vitamin supplementation, we repeated this experiment at 0 and 2 h post-feeding, with an additional treatment consisting of wCle-free bed bugs that received the full B-vitamin mix, as detailed in Table 1.

Erythrocyte lysis assays

We collected adult male wCle-present and wCle-free bed bugs of mixed ages from their respective colony jars and starved them for 7–10 d prior to feeding on blood without B-vitamin supplementation. At designated time-points immediately after feeding (0 h), and at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 36 h post-feeding, we destructively sampled the anterior midgut (AMG) contents. We pierced the cuticle just below the elytra using a dissection pin and placed a calibrated 10 µl microcapillary pipette onto the resulting fluid droplet, allowing AMG contents to be drawn up by capillary action. The volume of AMG fluid collected was recorded, and each sample was brought to a final volume of 10 µl using cold 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1X protease inhibitor cocktail III (Millipore Sigma, Cat#539134) to limit premature erythrocyte lysis. We diluted each sample as necessary, and loaded 10 µl aliquots of each sample into a hemocytometer to obtain erythrocyte counts. Erythrocyte counts were used to calculate the original erythrocyte concentration in the AMG. Due to individual variation in the size of the blood meal and the rate of diuresis, we normalized erythrocyte concentrations to the average erythrocyte concentration at 4 h post-feeding (Fig. 4). This time-point corresponded to the peak erythrocyte concentration prior to significant cell lysis, as diuresis causes a transient increase in erythrocyte concentration (Supplementary Information Fig. S2).

Hemoglobin and albumin digestion assays

To evaluate hemoglobin and albumin digestion, we collected freshly fed adult male wCle-present and wCle-free bed bugs of mixed ages from their respective colonies and starved them for 20 d before feeding on blood with no B-vitamin supplementation. At time-0 (immediately after feeding), whole wCle-present and wCle-free bed bugs were homogenized in 100 µl of PBS using a disposable pestle; these samples were used to determine baseline amount of hemoglobin and albumin in the blood meal. We used whole insects at this time point due to the difficulty of dissecting midguts from fully engorged bed bugs without rupturing them. Preliminary results confirmed no significant difference in hemoglobin content between whole-insect homogenates and dissected midguts within the first 2 d post-feeding (Supplementary Information Fig. S5). At 2, 4, 6, and 8 d post-feeding, midguts were dissected following a protocol modified from51, homogenized as above, and stored at -20 °C until analysis. The initial sample size was 10 bed bugs per group per time point; however, midguts damaged during dissection were excluded from analysis, resulting in n = 6–10 (Fig. 5). We quantified hemoglobin content using a high-sensitivity colorimetric hemoglobin assay (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat#EIAHGBC), and albumin content using a BCG albumin assay (Millipore Sigma, Cat# MAK124), following the manufacturers’ protocols. The raw data was corrected for the dilution in PBS to obtain hemoglobin or albumin content per insect or per insect midgut. One data point was identified as an outlier, and subsequently removed from the analysis.

To assess the effect of B-vitamin supplementation, we collected 125 adult male wCle-free bed bugs as described above and randomly assigned them to five treatment groups (n = 25 per group): (1) no vitamins (control), (2) full vitamin mix (B2, B7, B1, B6, and B9), (3) B2 only, (4) B7 only, and (5) B1, B6 and B9 mix. Vitamin stock solutions were added (10 µl of 100X solution per 1 ml) to reconstituted blood, yielding the concentrations listed in Table 1. Immediately post-feeding (0 d), five whole bed bugs per treatment were individually homogenized to quantify initial hemoglobin and albumin content in the blood meal. At 4 and 8 d post-feeding, midguts from 10 individual bed bugs per treatment were dissected and analyzed using hemoglobin and albumin assays, as described previously.

Of note, during the vitamin rescue experiments (Figs. 6 and 7), there was a signifcant difference in the initial hemoglobin content in wCle-free bed bugs by vitamin treatment, with the B2 only and B1, B6, and B9 mix treatments resulting in signifcantly higher hemoglobin content in bed bug midguts when compared to the no vitamin treatment. A similar pattern was observed for albumin, but the affect was not statistically significant. Thus, individual data points at 4- and 8-days post feeding were normalized to the mean of that treatment at 0-days post feeding. The non-normalized data for hemoglobin and albumin are shown in Supplementary Information Figs. S3 and S4, respectively.

Statistical analyses

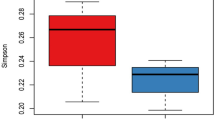

All statistical analyses were performed using JMP version 17 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), except for the Friedman test, which was conducted in R version 4.2.3 (R Core Team). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of all data sets. Data from diuresis and erythrocyte lysis experiments were not normally distributed, so nonparametric tests were employed. It is important to note that erythrocyte lysis and protein digestion experiments involved destructive sampling, with different individuals measured at each time point. In contrast, the diuresis experiments used non-destructive methods, allowing repeated measurements of the same individuals over time. Diuresis data were assessed using the Friedman test, the non-parametric equivalent of a repeated measures ANOVA. Two wCle-present samples were excluded from the Friedman test (n = 13) because there was no data collected at 24 h post feeding, and this analysis required continuity for all samples across each time point. These two samples were retained for Wilcoxon tests and visualization (n = 13–15) shown in Fig. 3. A one-way ANCOVA was used to compare slopes of the hemoglobin and albumin digestion data, with the P-value reported as the interaction term of Wolbachia-status * days post feeding. The albumin data were linearized using a log-transformation prior to the ANCOVA. Unless otherwise stated, we used an α-level of 0.05 for all analyses. We present summary data as box plots, showing all the replicates. The box represents the interquartile interval (middle 50% of the replicates) and the black horizontal line within the box is the median. Whiskers indicate all data points to the furthest points within 1.5 times the interquartile range, and potential outliers shown as individual points. In cases where outlier analyses were conducted, we used the Robust Fit Outliers approach in JMP, using the quartile method and a K sigma value of 4.

Data availability

The data generated during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Graça-Souza, A. V. et al. Adaptations against heme toxicity in blood-feeding arthropods. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 36, 322–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.01.009 (2006).

Sterkel, M., Oliveira, J. H. M., Bottino-Rojas, V., Paiva-Silva, G. O. & Oliveira, P. L. The dose makes the poison: nutritional overload determines the life traits of blood-feeding arthropods. Trends Parasitol. 33, 633–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2017.04.008 (2017).

Douglas, A. E. The B vitamin nutrition of insects: the contributions of diet, microbiome and horizontally acquired genes. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 23, 65–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2017.07.012 (2017).

Duron, O. & Gottlieb, Y. Convergence of nutritional symbioses in obligate blood feeders. Trends Parasitol. 36, 816–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2020.07.007 (2020).

Hickin, M. L., Kakumanu, M. L. & Schal, C. Effects of Wolbachia elimination and B-vitamin supplementation on bed bug development and reproduction. Sci. Rep. 12, 10270. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14505-2 (2022).

Hosokawa, T., Koga, R., Kikuchi, Y., Meng, X. Y. & Fukatsu, T. Wolbachia as a bacteriocyte-associated nutritional mutualist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 769–774. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0911476107 (2010).

Catagay, N. S., Akhoundi, M., Izri, A., Brun, S. & Hurst, G. D. D. Prevalence of heritable symbionts in Parisian bedbugs (Hemiptera: Cimicidae). Environ. Microbio Rep. 17, 783. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-2229.70054 (2025).

Kakumanu, M. L., DeVries, Z. C., Barbarin, A. M., Santangelo, R. G. & Schal, C. Bed Bugs shape the indoor microbial community composition of infested homes. Sci. Total Environ. 743, 140704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140704 (2020).

Meriweather, M., Matthews, S., Rio, R. & Baucom, R. S. A 454 survey reveals the community composition and core microbiome of the common bed bug (Cimex lectularius) across an urban landscape. PLOS ONE. 8, e61465. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061465 (2013).

Sakamoto, J. M. & Rasgon, J. L. Geographic distribution of Wolbachia infections in Cimex lectularius (Heteroptera: Cimicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 43, 8569. https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585(2006)43[696:gdowii]2.0.co;2 (2006).

Nikoh, N. et al. Evolutionary origin of insect–Wolbachia nutritional mutualism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 10257–10262. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1409284111 (2014).

Benoit, J. B. et al. Emerging roles of aquaporins in relation to the physiology of blood-feeding arthropods. J Comp. Physiol. B 184, 811–825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00360-014-0836-x

Krebs, H. A. Chemical composition of blood plasma and serum. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 19, 409–430. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.bi.19.070150.002205 (1950).

Te Brugge, V., Ianowski, J. P. & Orchard, I. Biological activity of diuretic factors on the anterior midgut of the blood-feeding bug, Rhodnius prolixus. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 162, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.01.025 (2009).

Maddrell, S. H. P. Excretion in the blood-sucking bug, Rhodnius prolixus Stål: II. The normal course of diuresis and the effect of temperature. J. Exp. Biol. 41, 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.41.1.163 (1964).

Tsujimoto, H., Sakamoto, J. M. & Rasgon, J. L. Functional characterization of Aquaporin-like genes in the human bed bug Cimex lectularius. Sci. Rep. 7, 3214. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03157-2 (2017).

Vaughan, J. A. & Azad, A. F. Patterns of erythrocyte digestion by bloodsucking insects: constraints on vector competence. J. Med. Entomol. 30, 214–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/30.1.214 (1993).

Balczun, C., Pausch, J. & Schaub, G. Blood digestion in triatomines - a review. Mitteilungen Dtsch. Ges Für Allg Angew Entomol. 18, 331–334 (2012).

Usinger, R. L. Monograph of Cimicidae (Hemiptera- Heteroptera). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 7, 526. https://doi.org/10.4182/BQCN5049.1966.vi (1966).

Saveer, A. M., DeVries, Z. C., Santangelo, R. G. & Schal, C. Mating and starvation modulate feeding and host-seeking responses in female bed bugs, Cimex lectularius. Sci. Rep. 11, 1915. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81271-y (2021).

Mellanby, K. The physiology and activity of the bed-bug (Cimex lectularius L.) in a natural infestation. Parasitology 31, 200–211. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000012762 (1939).

Reinhardt, K., Isaac, D. & Naylor, R. Estimating the feeding rate of the bedbug Cimex lectularius in an infested room: an inexpensive method and a case study. Med. Vet. Entomol. 24, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2915.2009.00847.x (2010).

Azevedo, D. O. et al. Notes on midgut ultrastructure of Cimex hemipterus (Hemiptera: Cimicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 46, 435–441. https://doi.org/10.1603/033.046.0304 (2009).

Billingsley, P. F. The midgut ultrastructure of hematophagous insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 35, 219–248. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.35.010190.001251 (1990).

Oliveira, P. L. & Genta, F. A. in Triatominae - Biol. Chagas Dis. Vectors. 265–284 (eds Guarneri, A. & Lorenzo, M.) (Springer International Publishing, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64548-9_12.

Rost-Roszkowska, M. M. et al. Investigation of the midgut structure and ultrastructure in Cimex lectularius and Cimex pipistrelli (Hemiptera: Cimicidae). Neotrop. Entomol. 46, 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13744-016-0430-x (2017).

Zug, R. & Hammerstein, P. Bad guys turned nice? A critical assessment of Wolbachia mutualisms in arthropod hosts. Biol. Rev. 90, 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12098 (2015).

Hilgenboecker, K., Hammerstein, P., Schlattmann, P., Telschow, A. & Werren, J. H. How many species are infected with Wolbachia? A statistical analysis of current data. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 281, 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01110.x (2008).

Moran, N. A., McCutcheon, J. P. & Nakabachi, A. Genomics and evolution of heritable bacterial symbionts. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42, 165–190. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130119 (2008).

Moriyama, M., Nikoh, N., Hosokawa, T. & Fukatsu, T. Riboflavin provisioning underlies Wolbachia’s fitness contribution to its insect host. mBio 6, e01732-15. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.01732-15 (2015).

Newton, I. L. G. & Rice, D. W. The Jekyll and Hyde symbiont: could Wolbachia be a nutritional mutualist? J. Bacteriol. 202, 1128 (2020).

Matos, Y. K., Osborne, J. A. & Schal, C. Effects of cyclic feeding and starvation, mating, and sperm condition on egg production and fertility in the common bed bug (Hemiptera: Cimicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 54, 1483–1490. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjx132 (2017).

Husnik, F. Host–symbiont–pathogen interactions in blood-feeding parasites: nutrition, immune cross-talk and gene exchange. Parasitology 145, 1294–1303. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182018000574 (2018).

Serrato-Salas, J. & Gendrin, M. Involvement of microbiota in insect physiology: focus on B vitamins. mBio 14, e02225–e02222. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.02225-22 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Effect of riboflavin deficiency on intestinal morphology, jejunum mucosa proteomics, and cecal microbiota of Pekin ducks. Anim. Nutr. 12, 215–226 (2023).

Pinto, J. T. & Zempleni, J. Riboflavin Adv. Nutr. 7, 973–975 doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aninu.2022.09.013. (2016).

Thakur, K., Tomar, S. K., Singh, A. K., Mandal, S., Arora, S. Riboflavin and health: a review of recent human research. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 57, 3650–3660. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2016.1145104 (2017).

Eichler, S. & Schaub, G. A. The effects of aposymbiosis and of an infection with Blastocrithidia triatomae (Trypanosomatidae) on the tracheal system of the reduviid bugs Rhodnius prolixus and Triatoma infestans. J. Insect Physiol. 44, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1910(97)00095-4 (1998).

DeVries, Z. C., Kells, S. A. & Appel, A. G. Effects of starvation and molting on the metabolic rate of the bed bug (Cimex lectularius L). Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 88, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1086/679499 (2015).

Araujo, R. N., Costa, F. S., Gontijo, N. F., Gonçalves, T. C. M. & Pereira, M. H. The feeding process of Cimex lectularius (Linnaeus 1758) and Cimex hemipterus (Fabricius 1803) on different bloodmeal sources. J. Insect Physiol. 55, 1151–1157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2009.08.011 (2009).

Fisher, M. L. et al. Growth kinetics of endosymbiont Wolbachia in the common bed bug, Cimex lectularius. Sci. Rep. 8, 11444. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29682-2 (2018).

Mock, D. M. Encycl. Hum. Nutr. Third Ed. 182–190 (Academic Press, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-375083-9.00026-X.

Kakumanu, M. L., Hickin, M. L. & Schal, C. Detection, quantification, and elimination of Wolbachia in bed Bugs. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ. 2739, 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-3553-7_6 (2024).

Jayaraj, S., Ehrhardt, P. & Schmutterer, H. The effect of certain antibiotics on reproduction of the black bean aphid, Aphis fabae Scop. Ann. Appl. Biol. 59, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7348.1967.tb04412.x (1967).

Li, G. et al. The physiological and toxicological effects of antibiotics on an interspecies insect model. Chemosphere 248, 126019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126019 (2020).

Sierras, A. & Schal, C. Comparison of ingestion and topical application of insecticides against the common bed bug, Cimex lectularius (Hemiptera: Cimicidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 73, 521–527. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.4464 (2017).

Romero, A. & Schal, C. Blood constituents as phagostimulants for the bed bug Cimex lectularius L. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 552–557. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.096727 (2014).

Jedrzejewska-Szczerska, M. & Gnyba, M. Optical investigation of hematocrit level in human blood. Acta Phys. Pol. A. 120, 642–646. https://doi.org/10.12693/APhysPolA.120.642 (2011).

Kao, K. N. & Michayluk, M. R. Nutritional requirements for growth of Vicia hajastana cells and protoplasts at a very low population density in liquid media. Planta 126, 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00380613 (1975).

Lake, P. & Friend, W. G. The use of artificial diets to determine some of the effects of Nocardia rhodnii on the development of Rhodnius prolixus. J. Insect Physiol. 14, 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1910(68)90070-x (1968).

Patton, W. S. & Cragg, F. W. A Textbook of Medical Entomology (Christian literature society for India, 1913).

Acknowledgements

We thank Richard G. Santangelo for assisting with experimental insects during this study. We also thank Dr. Gareth Powell for providing guidance and equipment for photographing bed bugs, Dr. Rocio Crespo for providing a hematocrit microcentrifuge, Dr. James Clothier for statistical guidance, and Drs. Marcé Lorenzen, Kelly Meiklejohn, and R. Michael Roe for constructive comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Funding

Elizabeth L. Wiles was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (Fellow ID: 2023348287), a Provost Doctoral Fellowship through the Genetics and Genomics Scholars Program (GGS) at North Carolina State University, a graduate student grant from the Triangle Center for Evolutionary Medicine, and Scholarship awards from the North Carolina Pest Management Association. This work was supported in part by the Research Capacity Fund (HATCH) project award no. NC02639 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and the Blanton J. Whitmire Endowment at North Carolina State University. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official funder determination or policy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: E.L.W., M.L.K., C.S.; Methodology: E.L.W., M.L.K., C.S.; Resources: E.L.W, M.L.K., C.S., Investigation: E.L.W.; Formal analysis: E.L.W.; Visualization: E.L.W., C.S.; Funding acquisition: E.L.W., C.S; Supervision: M.L.K., C.S.; Writing – original draft: E.L.W.; Writing – review & editing: E.L.W., M.L.K., C.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiles, E.L., Kakumanu, M.L. & Schal, C. Wolbachia-supplemented B-vitamins are critical for blood digestion in the bed bug Cimex lectularius. Sci Rep 15, 40962 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24795-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24795-x