Abstract

Aeromagnetic data acquired over the Obudu Plateau, Ikom Mamfe embayment, and Oban Massif was analyzed to evaluate the study area’s structural pattern and sedimentary thickness. Data filtering and other enhancement methods with 2-D forward modeling were applied to total magnetic intensity (TMI) data to evaluate the structural pattern, possible mineralization potential, sedimentary thickness, and basement framework disparity. To achieve this aim, several data enhancement techniques such as first vertical derivative (FVD), second vertical derivative (SVD), total horizontal derivative (THD), tilt angle derivative (TAD), analytic signal (AS), upward continuation (UC), low pass filter (LPF), high pass filter (HPF), Centre for Exploration Targeting (CET) and 2-D forward modeling were performed on the TMI data from which the buried subsurface structural lineaments and trends were unraveled. The structural lineaments delineated from the various enhancement operations revealed the major structural orientations of NE-SW. In contrast, the minor geologic structures trend in NNE-SSW, NW-SE, N-S, and E-W directions. These high frequency magnetic anomalies (geologic structures) are caused by post-depositional magmatic intrusions occurring at shallow depth and they have significant control over mineralization. They serve as migration pathways for hydrothermal fluids and accumulation zones for minerals. The depth estimation techniques like source parameter imaging (SPI), standard Euler deconvolution (SED) and 2D forward modelling employed in this study, revealed predominantly shallow depths (< 1400 m). These thin sedimentations are attributed to the widespread presence of Precambrian basement rocks in the Oban Massif and Obudu Plateau as well as the significant basaltic intrusions of Ikom-Mamfe Embayment. Furthermore, the 2-D forward model along the SW-NE profile revealed sediment thickness of 0–700 m overlying intruded metamorphic basement with magnetic susceptibility values ranging from 0.00001 to 0.00625 SI. The model which is highly undulant, revealed two sub-basins separated by the magmatic intrusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Detection of geological lineaments (geological boundaries, contacts, fractures, and faults) and their orientation can effectively be established by employing geophysical techniques1,2,3,4,5. Amid the airborne techniques, the aeromagnetic technique has been confirmed to have the utmost resolution to the delineation of structural lineaments and their distributary pattern even down deep the curie points of the geothermal gradient6,7,8. However, magnetic data has been employed for delineation of regional suburface rock boundaries1,9,10,11, assessment of minerals and detection of hydrothermally altered rock areas and geological structural features such as faults, sills, dykes3,4,12,13.

The study area which falls within the eastward trending arm of the Lower Benue Trough (called Ikom Mamfe Embayment), Obudu Plateau and Oban Massif, is characterized by series of post-depositional tectonic activities14,15,16,17. The magnetic and gravity signatures have been reported by several researchers14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

Although high-resolution aeromagnetic data are now available, our understanding of the spatial distribution, orientation, and structural importance of geological lineaments in the Ikom-Mamfe Embayment, Obudu Plateau, and Oban Massif is still limited14,16, as well as their influence on mineralization11,21,22,23. Many earlier studies depended on the outdated 1975 low-resolution dataset, which could not capture subtle geological details, leading to non-unique and often ambiguous interpretations11,14,15,16,17. As a result, the connection between these lineaments, regional tectonic evolution, mineralization potential, and hydrothermal fluid pathways remains unclear. In addition, challenges in magnetic data inversion and interpretation continue to make it difficult to accurately map basement structures, variations in sedimentary thickness, and fault-controlled mineralization zones15,16. To overcome these challenges, it is essential to apply advanced filtering, depth estimation, and modeling techniques to the new high-resolution aeromagnetic datasets, which promise to provide a clearer and more reliable picture of the structural framework and mineralization potential of the study area11,12,13.

To determine the dominant lineaments, orientations, influence on mineralization, and fluid flow, enhancement filters like FVD, SVD, THD, TAD, AS, UC), LPF, HPF and were used to highlight short and long-wavelength magnetic discontinuities. These lineaments serve as conduits for hydrothermal fluids, with shear zones and fault intersections often hosting mineral deposits3,5. Mineralization potential is highest along intersecting fault zones3,5. The depth results were correlated with existing magnetic and gravity results16,18 to validate structural interpretations, particularly in rift-related basins where deeper basement zones align with major fault systems11,21. 2D forward modeling and depth estimators like the SPI and SED were used to further refine depth models, revealing sedimentary thickness variations24,25,26. Higher-resolution data allows for better noise suppression and sharper edge detection when using advanced filters27,28,29,30. The finer grid spacing improves data enhancement and inversion accuracy, reducing ambiguity in magnetic source localization10,31,32. Compared to older datasets, the new data can resolve shallower and narrower structures, improving the detection of minor faults and fractures critical for mineralization studies13,33,34. The spatial distribution and orientation of lineaments are analyzed using directional filtering and rose diagrams to identify predominant trends. These trends can be correlated with regional tectonic stress regimes like the Benue Trough rifting14,16.

This study aims to analyze and interpret aeromagnetic data over the area under investigation, focusing on lineaments pattern and depth to the basement. These lineaments (faults, fractures, boundaries of lithology), which are associated with tectonic activities, have significant control on mineralization1,2,5,10,19,35,36,37. Thus, the location of these structural lineaments suggests the potential target or host for solid mineral deposits, hydrothermal fluid flow, and groundwater resource development21,35,38. Previous studies were carried out with sparse data sets. In contrast, the current analyses were carried out on aeromagnetic data collected at 100 m station intervals with flight line spacing of 500 m39, as opposed to the old NGSA 1975 data on 2 km flight line spacing. However, several methods used for magnetic data reduction, improvement, demonstration, and interpretations have greatly improved over time11. But, magnetic inversion problems usually related to magnetic data pose serious issues, making the solution unreliable and ambiguous3,10,11,40,41. A consistent solution to such difficulties can be solved by knowing sufficient information about geology and using suitable and improved methods of data analysis and interpretation18. This work gives an in-depth understanding of the study area, complementing existing knowledge and making recommendations for further studies in the region.

Geology and tectonic setting of the study area

This study is located in the South-eastern sector of Nigeria and its shares boundary with the Republic of Cameroon. It is found between latitude 5.300N and 6.300N and longitude 8.300E and 9.300E, covering three geological provinces comprising the Obudu Plateau (OP), Ikom Mamfe Embayment (IME), and Oban Massif (OM) (Fig. 1). The Obudu Plateau primarily reside in the northeastern portion of the study area overlapping into the Republic of Cameroon. The IME lies in the eastern portion of the study area and occupies the southeast portion of the Lower Benue Trough. OM bounds it in the south OP north and ends beneath the Cameroon Volcanic Line in the east.

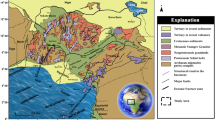

Geologically, the study area has two geological provinces, the Cretaceous sedimentary sequence and the Precambrian basement complex, comprising the IME as the Cretaceous basin and the basement complex comprising of the OP and OM. The OM is one of the Precambrian basement complexes in Nigeria bounded by the Cretaceous sediments. The area involves rocks such as phyllites, gneisses, amphibolies and schists, with dominant granite gneisses and migmatite occupying the eastern axis22. The OM is mostly composed of syntectonic granitoid and granodiorite in the Western region22. The basement blocks were highly characterized by granitic intrusions. The Obudu Plateau is bounded by the Benue Trough in the west and north and the Ikom-Mamfe Rift in the south. Several igneous intrusions characterized the dominant gneissic setting of the Precambrian Obudu Plateau42. These gneisses comprise biotite granite gneiss, migmatite gneiss, pyroxene gneiss, garnet hornblende gneiss and garnet sillimanite gneiss with little portion of schists42. Moreover, the Oban Massif and Obudu Plateau basement complexes are occupied by crystalline rock units (amphibolites - phyllites, chalcocite, and other igneous rocks)42. The Ikom Mamfe Embayment is an extended portion of the Lower Benue Trough in eastern Nigeria extending into the Republic of Cameroun, where it becomes narrower and finally terminates beneath the Tertiary-Recent sedimentary cover of the Cameroun volcanic line14,23,43 reported it as a significant tectonostratigraphic feature in Africa. The Cretaceous sediments dominate the IME with over 5.5 km of Tertiary-Recent intrusive and extrusive rock units such as diorites and basalts11,35. The igneous intrusions resulted in faulting or fracturing of basement rocks. Accordingly, the sedimentary section overlying the basement is sternly faulted, baked, strained, and arched44. These actions are prompted by Tertiary-Recent tectonism of the adjoining Cameroon Volcanic Province. The Ikom Mamfe Embayment, as reported by45, comprises shales, conglomerates, conglomeratic mudstones, sandstones, calcareous and carbonate rocks (Asu River Group), which lies above the Eze-Aku Group. Overlaid by the Asu River Group is the post-Santonian Nkporo Afikpo Shale Formation that specifically occupies the study area’s western and southwestern parts. The key rock units in the formation are the sandstone, mudstone, and shale beds39.

The lower part of the study area is circumscribed by the Oban Massif, which comprises the Precambrian basement complex underneath the Cretaceous-Tertiary sediments forming part of the Calabar Flank. The Oban Massif is Precambrian in age and is characterized by regional metamorphism triggered by volcanic activities. It is influenced by the pan-African orogeny. The oldest rock here is the Branded Gneiss46. This basement complex has experienced a series of metamorphic and igneous deformation47.

Geology map of the area showing the study location (https://ngsa.gov.ng/geological-maps/).

Materials and methodology

The data used

The data used for this study is the anomalies map of total magnetic intensity (TMI) acquired from the Nigerian Geological Survey Agency (NGSA) Abuja (Fig. 2). The data acquisition was carried out by Fugro Airborne Surveys using three optically pumped magnetometers mounted on seven aircraft flown at 80 m constant height above ground. The flight is 135° (NW-SE) direction, the flight lines interval is 500 m and the tie lines flown at 45° (NE-SW) were separated at 5000 m apart. The data recording was done at a spacing of 100 m. Necessary reductions (diurnal reduction, instrument variation, and aircraft heading, were carried out using the data from the contractor. The data analysis used Geosoft Oasis Montaj (version 8.4).

Anomalies of total magnetic intensity data (By Geosoft version 8.4, https://www.seequent.com/products-solutions/oasis-montaj/).

Methods

The magnetic method is popularly used because of its ease and cheap approach for detecting near-surface lineament. However, certain rocks have magnetic content to produce reasonable magnetic anomalies. The data interpretation that shows differences of rock magnetization present on a local scale is principally helpful for detecting lineaments (faults and geologic contacts)48.

First vertical derivative

The first vertical derivative is employed to enhance magnetic signatures. It pinpoints near-surface magnetic sources by magnifying their anomalies and eliminating regional magnetic trends, making it simpler to identify localized anomalies49. Additionally, the FVD is used to detect high-frequency structures more confidently, particularly if they are covered by high amplitude and low-frequency anomalies. The formula for FVD is given by

where A is the magnetic anomaly field intensityand \(\:\frac{\partial\:A\:}{\partial\:z}\) is the vertical derivative.

The second vertical derivative

The Second Vertical Derivative technique amplifies noise because of the higher order of the derivation filter. However, its application requires high-quality data35,50. SVD is expressed as:

where A is the magnetic anomaly field intensity value.

At a higher-order derivative above the second order, the noise becomes clearer than the signal. The formula for the wave-number domain filter to generate the nth derivative is given by35,50.

Horizontal derivative technique

The horizontal gradient technique was employed on the residual map in order to match peaks or ridges to linear anomalies (faults). This technique, THD, is the most frequently used edge-detecting filter48. THD is mathematically defined as:

where A is the magnetic anomaly field intensity, \(\:\frac{\partial\:A}{\partial\:x}\:and\:\:\frac{\partial\:A}{\partial\:y}\) are the two orthogonal horizontal derivatives of the magnetic data in the x and y direction respectively.

The Tilt angle derivative (TAD) is a first order derivative technique and as such it is insensitive to noise when compared to the second and third order derivatives enhancement methods which amplified the noise. TAD is used to map the edges of geologic structures (faults, fractures, and lithological contact/boundaries) generating magnetic anomalies. The TAD is given by:

The TAD is defined as the anomalies’ vertical-derivative divided by their horizontal derivative. The formula is as follows:

where \(\:\frac{{\partial\:}^{2}A}{\partial\:{z}^{2}}\) is the vertical derivative of the magnetic anomaly field intensity, and THD which is well-defined as Eq. (4), is a widely employed edge detection filter48.

Analytical signal

The analytical signal technique centered anomaly over their causative body51. This technique is usually used at low magnetic latitudes51 applied three orthogonal derivatives of the magnetic data to describe the amplitude of the AS:

where \(\left| {A{S_{\left( {x,y} \right)}}} \right|\) is the analytical signal amplitude, A is the magnetic anomaly field intensityin (x, y) axes, and \(\:\frac{\partial\:A}{\partial\:x},\:\:\frac{\partial\:A}{\partial\:y}\:and\:\frac{\partial\:A}{\partial\:z}\) are the orthogonal components in the x, y, and z coordinates, respectively.

Center for exploration targeting

The Center for Exploration Targeting analysis is employed to evaluate textural and structural complexity, delineate lineaments, and vectorization of these lineaments. This technique is applied to perform several tasks on the TMI data, such as textural analysis, determination of boundaries or edges of structures, identification of lineaments, and detection of the structural pattern of the area under investigation35,52,53,54. The determination of the trend menu is programmed particularly for the delineation of discontinuities in potential field data. The entropy and standard deviation are the two approaches employed here to estimate the trends35,52,53,54. The formula below is used to calculate the entropy55,56:

where the E = entropy, P = probabability and n = number of bins.

The standard is given as:

The deviation estimates an approximate value of the data inconsistency locally. Thus, for N number of cells window, µ = average value of cells, σ = the standard deviation, and xi = the cell value.

Plotting of Rose diagrams

Linear features were digitized in ArcMap to produce lineaments maps. The geographic coordinates of the lineaments were saved on MS Excel and used to plot rose diagrams.

Source parameter imaging

The SPI characteristically creates the outputs of imageries from which depth to magnetic bodies can be observed57. Based on57, this technique analyses the qualities of the analytic signal and second vertical-derivative responses. The analysis can offer an appropriate geologic model, and unlike the SED57, the depth approximation is not dependent on any assumptions made on the geologic model. Also, it is unnecessary to subject the input grid to a reduction-to-pole procedure as the estimated depth values are non-reliant on the angle of the inclination and declination of the magnetic field. When one has a full understanding of the geology of the study location, magnetic data analysis become remarkably simpler58. The wavelength of the ASIG is characteristically where the SPI approximations of depth come from. The ASIG based on59, A1(x, z) is given as:

j is the imaginary number, x and z are Cartesian coordinates for the horizontal and the vertical directions perpendicular to the strike respectively, and M(x, z) is the magnitude of the anomalous total magnetic field.

Standard Euler Deconvolution

The SED was formulated by60 as a programmed interpretation method for calculating approximately the location of 2-D magnetic anomalous sources along profile data. Thereafter, the method was used on gridded data61. Today, the method has gained wide publicity for both magnetic and gravity field data analyses for semi-automatic and automated interpretation because of its ease of operation, coupled with the fact that it is used for automatic estimation of causative source locations and their depths. The Euler homogeneity equation provides apparent depth to the magnetic bodies. This technique connects the magnetic field and its gradient components to the location of magnetic anomaly, with the degree of homogeneity described as a structural index (SI). The Euler’s homogeneity equation for magnetic data can be stated as:

where (x0, y0, z0) is the location of the magnetic source whose total field (T) is observed at (x, y, z). N, a measurement of the magnetic field fall-off rate, can be taken to be the SI, and B is the local magnetic field. The method involves selecting a suitable SI value and determining the equation for the best x0, y0, z0 and B by means of least-square inversion. Furthermore, a square window size that describes the number of gridded data cells to be applied in the inversion at each chosen solution must be provided.

Upward continuations

Upward continuations are used to remove or reduce the effects of noise and shallow sources in the gridded data to enhance or improve the deeper sources anomaly. Upward continuation was performed on the TMI data to a depth of 1,000 m (1 km). Mathematically, upward continuation is expressed as:

Where; F (x′, y′, −ℎ) is the total field at the point P(x′, y′, −ℎ) above the surface on which F(x′, y′, 0)) is known, while h is the elevation above ground surface.

Wavelength filtering

Wavelength filtering employed in this work involves low-pass filtering (LPF) and high-pass filtering (HPF) of magnetic data. Filtering magnetic data involves qualitative interpretation, which divulges magnetic relief and textures21. Magnetic relief mainly includes the amplitude of anomaly, which is relatively objective, whereas magnetic texture involves the size, shape, and continuity of adjacent anomaly, which is further subjective. Variations in geology that show rock magnetization give rise to variations in texture and relief. When rock magnetization is faint, anomalies are quiet, and wavelength filtering is essential to reveal the variations2. Generally, it is believed that shallow magnetic sources produce short wavelength anomalies, whereas long wavelengths come from deep magnetic bodies. These different sources of magnetization are fused in the observed TMI map. They should be separated before lineament analysis to differentiate regional lineaments from those associated with intrusives or sedimentary fill. Using Fourier transform analysis before spectrum calculation in Oasis Montaj to obtain the cut-off wavelength, which was produced from a segment of the graph using the relation;

where λ is the wavelength, π is a constant, and k is the wave number.

2-D forward modeling

To reveal the basement image (depth and magnetic susceptibility), a 2.75D forward model was employed since the geologic setting of the study region is very familiar. A potential model was created using the GM-SYS extension of Oasis Montaj to interpret the observable regional magnetic field. This involved digitizing a profile from the Oban Massif in the southwest through the Ikom Mamfe Embayment up to the Obudu Plateau in the northeast of the study area. To model the profile, we employed the Geosoft database and Gridprof programs, from which the data along the digitized profile were saved to the database, and the appropriate channels were exported to the GM-SYS extension for modeling. The model was generated by iteration until a realistic fit of the calculated and observed values matched with minimum root mean square error62. The model result is utilized in the last part of the interpretation to reveal the subsurface architecture. A model is simply a structure with parameters such as size, shape, depth, and susceptibility that shows information about the measured data63.

Results

For aeromagnetic data interpretation, areas described by high frequency anomalies are often allied to zones of mineralization and complex geologic structure2,11,64. The TMI data were subjected to both short and long wavelength enhancement operations, CET grid analysis, SPI and SED depth estimators and 2D forward modelling (Fig. 3). The short and long wavelength filters accentuated the geologic structural signatures originating from near surface and deeply seated magnetic sources respectively. The First and Second Vertical Derivative maps (Fig. 4) were generated by applying the FVD and SVD filters on the TMI map (Fig. 2). These derivatives enhancement filters were deployed to filter the TMI data. The Oban Massif and Obudu Plateau, predominated by Precambrian metamorphic and igneous basement blocks, occupy the southeastern and northeastern parts of the study location, respectively. In contrast, the Ikom Mamfe Embayment, characterized by the Cretaceous sediments, occupied the east-central part of the study area. These regions are distinctively identified by thickly filled red to magenta color. The basement blocks are mainly comprised of granites and biotite-gneisses64, which are made of magnetite and are considered to be the reason for the high magnetization observed in those areas. The filters divulge the locations of magnetic lineaments or edges (fault, boundaries, and contacts of the magnetic source bodies). It also reveals the region occupied by the sediments, indicated by the blue and green colors, and the area occupied by the basement, indicated with red and magenta colors. The FVD and SVD maps show that they agree with each other, further strengthening the fact that the filters are excellent tools for edge detection.

The Total Horizontal Derivative (THD) map (Fig. 5a) delineated the source body location. It reveals several liner patterns and geometric structures. The Tilt angle derivative (TAD) map (Fig. 5b) shows lineaments that are dominant in the Obudu Plateau and Ikom Mamfe Embayment and are trending in the NE-SW direction analogous to the Benue Trough in Nigeria. A comparison of the THD and TAD maps (Fig. 5a and b) shows a good match and reveals the lineation within this region. The tectonic activities in the region gave rise to geologic structures triggered by the intrusion of non-metamorphosed minerals like granites, feldspar, quartz moods and basalt intrusions into Obudu Plateau Precambrian Basement and the Cretaceous sediments of the Ikom Mamfe Embayment11,65,67. Reference11 reported that regions described by complex geological structures formed by igneous intrusions are usually related to mineralization. Thus, to delineate such regions, substantial emphasis was focused on high-frequency anomalies on the improved map. Therefore, to clearly visualize the short wavelength anomalies which are of exploration interest we eliminate the magnetic effect emanating from deep-seated structures (long wavelength anomalies) by applying the High pass filtering (HPF) with a cut-off wavelength of 30 m on the TMI data (Fig. 6a). However, in order to delineate the edges of causative source bodies, particularly in a low magnetic latitude where remanence magnetization makes interpretation ambiguous, we employed analytical signal (AS) technique on the TMI data (Fig. 6b). Analytical signal operation is best appreciated at low magnetic latitudes because it aligned the anomaly directly over the causative bodies and clearly mapped edges of these bodies68,69. The Analytical signal map (Fig. 6b) clearly reveals areas with peak values represented by the pink color averaging 0.1185 nTm− 2 and the least values represented by the blue color averaging 0.0025 nTm− 2 of magnetic field intensities as shown in the map. Moreover, distant sections with low magnetic anomalies denoted by the blue-green colour show portions with low frequency (long wavelength) anomalies. To visualize these anomalies, the TMI data were upward continued to 1000 m (Fig. 7a), and a Low pass filter (LPF) was also applied with a cut-off wavelength of 5,000 m (Fig. 7b) in order to remove the magnetic effects due to near-surface magnetic bodies. These filtering methods clarified the key tectonic elements and crustal rock bodies domiciled in the region. Both maps revealed deeply concealed intrusions trending NE-SW and E-W directions. As well as the main weak zones indicated by the blue and green colors are supposed to be deep-seated faults corresponding with the positions of the adjoining sub-basins. The correlation of the upward continuation to a height of 1,000 m and low pass filtering with a cut-off wavelength of 5,000 m maps (Fig. 7) shows a very close match between the two filters. Nevertheless, the use of the Centre Exploration Targeting (CET) technique affords us the opportunity to thoroughly map and evaluate the broadly concealed geological features, orientation, and their interpretation. The result of the CET technique helps to improve our understanding of the multifaceted structural pattern of the region under investigation. Application of the CET grid examination resulted in the identification of favorable exploration targets that can be mapped within the study area70,71. Figure 8 revealed these geologic structures and their orientation (NE–SW, NNE–SSW, NW–SE, and E–W) with major NE–SW, and NW–SE and minor E–W orientation of lineaments. In the long run, the CET analysis gives rise to the creation of a good complex structural map, which is a valued tool for exploration of minerals. Furthermore, Fig. 9 showed SPI and SED results of varied depth to the basement of the study area. These techniques revealed the distribution of deep and shallow sources of magnetic bodies57. The depth to the basement ranges from 100 m to 1,300 m, as revealed from the maps (Fig. 9a and b). Interestingly, the 2-D modeling (Fig. 10) revealed the basement topography and marked the breaks in the magnetic signature. These breaks indicate weak zones within the basement block, which created an opening for magmatic intrusions11,18,72. The model also shows how the Precambrian OP and OM basement were intruded by the Quaternary–Recent intrusion, which further extended into the Cretaceous sediment of the IME. This intrusion resulted in the formation of two sub-basins separated by the Quaternary—Recent intrusion with susceptibility of 0.00625 SI as shown in (Fig. 10). These geologic structures are related to the Abakalilki Anticlinorium and the Cameroon Volcanic line as reported by65,73,74 triggering the widespread up-lifting, faulting, fracturing, and baking of the sedimentary sequence3,64,74.

(a) FVD and (b) SVD maps of the study area (By Geosoft version 8.4, https://www.seequent.com/products-solutions/oasis-montaj/).

(a) THD and (b) TAD maps of the study area (By Geosoft version 8.4, https://www.seequent.com/products-solutions/oasis-montaj/).

(a) HPF and (b) AS maps of the study area (By Geosoft version 8.4, https://www.seequent.com/products-solutions/oasis-montaj/).

(a) UC (of TMI to 1000 m); and (b) LPF (with a cut-off wavelength of 5000 m) maps of the study area (By Geosoft version 8.4, https://www.seequent.com/products-solutions/oasis-montaj/).

SPI and SED maps of the study area (By Geosoft version 8.4, https://www.seequent.com/products-solutions/oasis-montaj/).

The 2-D forward model of the study area (By Geosoft version 8.4, https://www.seequent.com/products-solutions/oasis-montaj/).

Discussion

Considerable improvements in magnetic data analysis and interpretation, coupled with geological information, have enhanced our understanding of linear features and their distribution patterns. This advancement has led to a better prospect of accurately detecting mineral and hydrothermal resource deposits2,35,75. The improved data enhancement techniques have enabled the mapping of geologic structures related to mineralization2,10,18,36,76. Figures 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 revealed lineaments with various orientations (NE–SW, NNE–SSW, NW–SE, and E–W). The FVD and SVD maps (Fig. 4a and b) revealed the dominance of the Precambrian metamorphic and igneous basements rocks that coincide with the Oban Massif and Obudu Plateau at the southeastern and northeastern parts of the study area respectively. The basement blocks comprise largely granites and biotite-gneisses64 dominated by magnetite. The FVD and SVD results agree with the findings of previous researchers in the Lower Benue Trough72,74,77. However, THD map (Fig. 5a) reveals the magnetic sources characterized by several linear patterns and geometric structures. In addition, the TAD map (Fig. 5b) showed lineaments in the Obudu Plateau and Ikom Mamfe Embayment that trend in the NE-SW direction analogous to the Benue Trough in Nigeria. A comparison of the THD and TAD maps (Fig. 5) shows a good match and reveals the lineation within this region18,76,77. These results were validated with the HPF map (Fig. 6a) with cut-off wavelength of 30 m. These geologic structures are caused by tectonic activities triggered by the intrusion of non-metamorphosed minerals such as granites, quartz, feldspar moods and basaltic intrusions into Obudu Plateau and Oban Massif Precambrian Basement extending into the Cretaceous sediments of the Ikom Mamfe Embayment11,65,66,67. Regions described by complex geological structures formed by igneous intrusions are usually related to mineralization11,76. On the whole, the AS map (Fig. 6b) clearly revealed the magnetic sources that created the observed lineaments. Additionally, regions dominated by low magnetic anomalies are characterized by long wavelength anomalies11,76. The UC and LPF maps (Fig. 7) revealed deeply concealed intrusions trending in the NE-SW and E-W directions that have been previous reported11,18,76,78. These weak zones indicating deeply seated faults are related to the Chain and Charcot fault zones72,79. Furthermore, the CET (Fig. 8) showed a multifaceted structural patterns indicating favorable exploration targets within the study area70,71. The observed geologic structures (Fig. 8) were characterized with major (NE–SW) and minor (E–W, NW–SE, and NNE–SSW) trends. The regional geologic study by Benkhelil (1987) revealed that the key structural configuration of the Obudu Basement Complex, Benue Trough, Oban Massif and Abakaliki Anticlinorium, is NE-SW direction, while some E-W and N-S lineaments orientations are regarded as transverse geologic structures to the predominant NE-SW and NNE-SSW fractures.

Furthermore, the depth estimators like the SPI and SED methods (Fig. 9) used in this study showed depth values generally less than 1400 m. The shallow depth is caused by the dominance of Precambrian basement rocks in the Oban Massif and Obudu Plateau12,66,67 as well as extensive invasion of the Ikom Mamfe Embayment by basaltic intrusions related to the Cameroun Volcanic Line11,65,74. The 2-D model (Fig. 10) divulged the basement configuration and the weak zones in the basement that created openings for igneous intrusions11,72. The weak zones with the basement areas caused the massive invasion of the Precambrian basement by younger granites, dolerites, and quartzo-feldspathic80,81,82. These invasions caused series of metamorphism70, folds, faults, and shear zones71,81 with N-S, NNE-SSW, NW-SE, NE-WS, and E-W arrangements, reflecting the regional strike of lineaments associated with the Pan-African orogeny and succeeding post-orogenic events71,81. The polyphase deformational history of the basement rocks reflects various occurrences of tectonic events81 that have influenced the geometry of the basement rocks64,71,74,81. On the whole, the study area is characterized by polymetallic-magmatic hydrothermal and metallogenic deposits12,64,74, Chain and Charcot fault zones79, igneous intrusions72, hydrothermal alterations72,79, brine fields83,84,85, and geologic structures associated with thermo-tectonic disturbances65,71,81,86,87,88.

Conclusion

The interpretation of aeromagnetic data over the Obudu Plateau, Ikom-Mamfe Embayment, and Oban Massif has provided critical insights into the structural framework, sedimentary architecture, and mineralization potential of the region. Through the application of advanced data filtering and enhancement techniques like FVD, SVD, THD, TAD, AS, UC, LPF, HPF, CET grid analysis, and 2-D forward modeling, key geologic structures and magnetic anomalies were effectively delineated. The identified structural lineaments predominantly trend NE-SW, with subordinate trends in NNE-SSW, NW-SE, N-S, and E-W orientations, reflecting complex tectonic reactivations and magmatic imprints. The high-frequency magnetic anomalies are attributed to shallow-seated magmatic intrusions, which play a pivotal role in the localization of mineralization by acting as conduits for hydrothermal fluid migration and zones for mineral deposition. Depth estimation techniques such as SPI, SED, and 2-D forward modeling consistently indicated shallow magnetic source depths (< 1400 m), corresponding to limited sedimentary cover across the study area. These results affirm the dominance of exposed and near-surface Precambrian crystalline basement in the Oban Massif and Obudu Plateau, and the basaltic influx associated with the Ikom-Mamfe Embayment. The 2-D forward modeling along the SW-NE profile revealed a sedimentary succession of 0–700 m overlying a variably intruded metamorphic basement, characterized by magnetic susceptibility values ranging from 0.00001 to 0.00625 SI. The subsurface geometry, marked by two distinct sub-basins separated by a pronounced magmatic body, underscores a structurally heterogeneous basement configuration. Collectively, these findings underscore the area’s mineralization potential, particularly in zones of magmatic concentration and structural complexity, and provide a geophysical framework for future mineral exploration initiatives in southeastern Nigeria.

Data availability

The data used in this study can be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Al-Badani, M. A. & Al-Wathaf, Y. M. Using the aeromagnetic data for mapping the basement depth and contact locations, at Southern part of Tihamah region, Western Yemen. Egypt. J. Pet. 27, 485–495 (2018).

Eze, O. E. et al. Delineation of deep-seated crustal structures from magnetic data in the southeastern part of the Niger delta basin, Nigeria. Front. Earth Sci. 12, 1439199 (2024).

Ekwok, S. E., Akpan, A. E., Kudamnya, E. A. & Ebong, D. E. Assessment of groundwater potential using geophysical data: a case study in parts of cross river State, south–eastern Nigeria. Appl. Water Sci. 10, 144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-020-01224-0 (2020).

Eldosouky, A. M. & Elkhateeb, S. O. Texture analysis of aeromagnetic data for enhancing geologic features using co-occurrence matrices in Elallaqi area, South Eastern Desert of Egypt. NRIAG J. Astron. Geophys. 7, 155–161 (2018).

Eldosouky, A. M. et al. Delineation of structural lineaments of Southeast Nigeria using high resolution aeromagnetic data. Open. Geosci. 14 (1), 331–340 (2022).

Chen, W., Ban, H., Mao, C., Liang, H. & Jiang, M. Sediment dynamics subject to sea level rise in the Yangtze river estuary. J. Ocean. Univ. China. 23 (6), 1572–1582 (2024).

Abdelrahman, K. et al. Exploratory mapping of the geothermal anomalies in the neoproterozoic Arabian shield, Saudi Arabia, using magnetic data. Minerals 13 (5), 694 (2023).

Eldosouky, A. M. et al. Appraisal of geothermal potentials of some parts of the Abakaliki anticlinorium and adjoining areas (Southeast Nigeria) using magnetic data. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1216198 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Planet craters detection based on unsupervised domain adaptation. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 59 (5), 7140–7152 (2023).

Ben, U. C. et al. Gómez-Ortiz, D. Interpretation of magnetic anomalies by simple geometrical structures using the manta-ray foraging optimization. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 849079 (2022).

Ekwok, S. E., Akpan, A. E. & Ebong, D. E. Enhancement and modeling of aeromagnetic data of some inland basins, southeastern Nigeria. J. Afr. Earth Sc. 155, 43–53 (2019).

Ekwok, S. E. et al. Mapping of geological structures and sediment thickness from analysis of aeromagnetic data over the Obudu basement complex of Nigeria. J. Geophys. Eng. 21 (2), 413–425 (2024).

Ekwok, S. E. et al. Unveiling the mineral resources and structural patterns in the middle Benue trough: a comprehensive exploration using airborne magnetic and radiometric data. Geocarto Int. 39 (1), 1–23 (2024).

Fairhead, J. D., Okereke, C. S. & Nnange, J. M. Crustal structure of the Mamfe Basin, West Africa, based on gravity data. Tectonophysics 186, 351–358 (1991).

Obi, D. A., Obi, E. O. & Okiwelu, A. A. Basinal configuration and intrasediment intrusives as revealed by aeromagnetic data of Southeast sector of Mamfe basin Nigeria. IOSR J. Appl. Geol. Geophys. 1 (5), 1–8 (2013).

Okereke, C. S. Contrasting modes of rifting: the Benue trough and Cameroon volcanic Line, West Africa. Tectonics 7 (4), 775–784 (1988).

Nzeuga, A. R., Nouajou, R., Nyam, F. E. & Fairhead, J. D. The use of aeromagnetic data interpretation to characterize the features in the Mamfe sedimentary basin Cameroon and a part of the East of Nigeria. Int. J. Sci. Res. 6 (11), 617–624 (2017).

Ekwok, S. E., Akpan, A. E., Achadu, O. I. M. & Ulem, C. A. Implications of tectonic anomalies from potential field data in some parts of Southeast Nigeria. Environ. Earth Sci. 81, 1–15 (2022).

Ekwok, S. E. et al. Gómez-Ortiz, D. Depth Estimation of sedimentary sections and basement rocks in the Bornu Basin, Northeast Nigeria, using high- resolution airborne magnetic data. Minerals 12 (3), 285 (2022).

Ekwok, S. E. et al. Application of the enhanced horizontal gradient amplitude (EHGA) filter in mapping of geological structures involving magnetic data in southeast Nigeria. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 34 (8), 102288 (2022).

Okiwelu, A. A. et al. Magnetic anomaly patterns, fault-block tectonism and hydrocarbon related structural features in the Niger delta basin. IOSR J. Appl. Geol. Geophys. 2 (1), 31–46 (2014).

Oden, M. I., Umagu, C. I. & Udinmwen, E. The use of jointing to infer deformation episodes and relative ages of minor cretaceous intrusives in the Western part of Ikom-Mamfe Basin, southeastern Nigeria. J. Afr. Earth Sc. 121, 316–329 (2016).

Nguimbous-Kouoh, J. J. et al. Structural interpretation of the Mamfe sedimentary basin of Southwestern Cameroon along the Manyu river using audiomagnetotellurics survey. Geophysics 4 (5), 34–65 (2012).

Yuan, Y. et al. Real-time joint filtering of gravity and gravity gradient data based on improved Kalman filter. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1, 1 (2024).

Liu, G. et al. Impact failure and disaster processes associated with rockfalls based on three-dimensional discontinuous deformation analysis. Earth. Surf. Proc. Land. 49 (11), 3344–3366 (2024).

Cao, D. et al. Correction of linear fracture density and error analysis using underground borehole data. J. Struct. Geol. 184, 105152 (2024).

Yin, Y. et al. Integrated geophysical prospecting for deep ore detection in the Yongxin gold mining area, Heilongjiang, China. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 7258 (2025).

Wang, L., Zhang, Y., Han, R. & Li, X. LA-ICP-MS analyses of trace elements in zoned sphalerite: A study from the Maoping carbonate-hosted Pb-Zn(-Ge) deposit, Southwest China. Ore Geol. Rev. 157, 105468 (2023).

Runsheng, H. et al. Geology and geochemistry of Zn-Pb (-Ge-Ag) deposits in the Sichuan-Yunnan-Guizhou triangle area, china: A review and a new type. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1136397 (2023).

Wang, R. et al. CGBi_YOLO: Lightweight land target detection network. Land 13 (12), 2060 (2024).

Gan, B. et al. Phase transitions of CH4 hydrates in mud-bearing sediments with oceanic laminar distribution: mechanical response and stabilization-type evolution. Fuel 380, 133185 (2025).

Niu, Q. et al. Inversion and optimization of CO2 + O2in situ leaching of blasting-stimulated sandstone-type uranium deposits. Phys. Fluids. 37 (3), 1 (2025).

Niu, Q. et al. Explosive fracturing mechanism in low-permeability sandstone-type uranium deposits considering different acidification reactions. Energy 312, 133676 (2024).

Huang, L. et al. Overburden movement law in strip filling mining of upward mining faces. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 1378 (2025).

Ekwok, S. E., Akpan, A. E. & Kudamnya, E. A. Exploratory mapping of structures controlling mineralization in Southeast Nigeria using high-resolution airborne magnetic data. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 162, 103700 (2020).

Ekwok, S. E., Akpan, A. E. & Ebong, E. D. Assessment of crustal structures by gravity and magnetic methods in the Calabar flank and adjoining areas of southeastern Nigeria case study. Arab. J. Geosci. 14 (4), 1–10 (2021).

Ekwok, S. E. et al. Gómez-Ortiz, D. Application of high-precision filters on airborne magnetic data: A case study of the Ogoja Region, Southeast Nigeria. Minerals 12 (10), 1227 (2022).

Alfaifi, H. J. et al. Exploratory assessment of geothermal resources in some parts of the middle Benue trough of Nigeria using airborne potential field data. J. King Saud University-Science. 35 (2), 102521 (2023).

Nigerian Geological Survey Agency (NGSA). Geological and Mineral Resources Map of Cross River State, Nigeria (2006).

Ben, U. C. et al. Investigating the applicability of the social spider optimization for the inversion of magnetic anomalies caused by dykes. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 35 (3), 102569 (2023).

Essa, K. S. & Elhussein, M. A new approach for the interpretation of magnetic data by a 2-D dipping dike. J. Appl. Geophys. 136, 431–443 (2017).

Ukwang, E. E., Ekwueme, B. N. & Horsley, R. J. Petrology of granulite facies rocks in Ukwortung area of Obudu Plateau, southeastern Nigeria. Glob J. Geol. Sci. 1 (2), 159–167 (2003).

Tabod, C. T., TokamKamga, A. P., Manguelle-Dicoum, E., Nouayou, R. & Nguiya, S. An Audio-Magnetotelluric Investigation of the Eastern Margin of the Mamfe Basin, Cameroon (The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics, 2008).

Akpan, A. E., Ugbaja, A. N. & George, N. J. Integrated geophysical, geochemical and hydrogeological investigation of shallow groundwater resources in parts of the Ikom Mamfe embayment and the adjoining areas in cross river State, Nigeria. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 70, 1435–1456 (2013).

Dumort, J. C. Carte géologique de reconnaissance et note explicative sur la feuille Douala-Ouest (1:500000). République Fédérale du Cameroon, vol. 69 Direction des Mineset de la Géologie du Cameroon (1968).

Ekwueme, B. W. Basaltic magnetism related to early stages of Benue trough, the study dolerites of Smith Eastern Nigeria. Geol. J. 29, 269–276 (1994).

Ekwueme, B. N. Rb-Sr ages and petrologic features of precambrian rocks from the Oban Massif southeastern Nigeria. Precambrian Res. 47, 271–286 (1990).

Blakely, R. J. Potential Theory in Gravity and Magnetic Applications (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Cooper, G. R. J. & Cowan, D. R. Enhancing potential field data using filters based on the local phase. Comput. Geosci. 32, 1585–1591 (2006).

Reeves, C., Reford, S. & Millingan, P. Airborne geophysics: old methods, new images. In Proceedings of the Fourth Decennial International Conference on Mineral Exploration (ed Gubins, A.) 13–30 (1997).

Roest, W. R., Verhoef, J. & Pilkington, M. Magnetic interpretation using the 3-D analytic signal. Geophysics 57 (1), 116–125 (1992).

Kovesi, P. Symmetry and asymmetry from local phase. AI’97. Tenth Australian Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 2–4 December 1997 (1997).

Kovesi, K. Image features from phase congruency. Videre J. Comput. Vis. Res. 1, 1 (1991).

Lam, L., Lee, S-W. & Suen, C. Y. Thinning methodologies—a comprehensive survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 14, 879 (1992)

Holden, E. J., Kovesi, P. & Dentith, M. Detection of regions of structural complexity within aeromagnetic data using image analysis. In Twenty Fifth International Conference of Image and Vision Computing New Zealand, 8–9 November, 2010 (2010).

Holden, E. J., Dentith, M. & Kovesi, P. Towards the automatic analysis of regional aeromagnetic data to identify regions prospective for gold deposits. Comput. Geosci. 34, 1505–1513 (2008).

Smith, R. S., Thurston, J. B. & Dai, T. MacLeod, I. N. iSPITM the improved source parameter imaging method1. Geophys. Prospect. 46, 141–151 (1998).

Thurston, J. B. & Smith, R. S. Automatic conversion of magnetic data to depth, dip, and susceptibility contrast using the SPITM method. Geophysics 62, 807–813 (1997).

Nabighian, M. N. Towards the three-dimensional automatic interpretation of potential field data via generalized hilbert transforms. Fundamental Relations: Geophys. 53, 957–966 (1984).

Thompson, D. T. & EULDPH A technique for making computer assisted depth estimates from magnetic data. Geophysics 47, 31–37 (1982).

Reid, A. B., Allsop, J. M., Granser, H., Millett, A. J. & Somerton, I. W. Magnetic interpretation in three dimensions using Euler Deconvolution. Geophysics 55, 80–91 (1990).

Gamel, Z. A., Mahmoud, A. A. & Haby, S. M. 2D and 3D modeling of airborne magnetic data to estimate depth to basement at the southeastern part of Egypt. Assiut Univ. J. Multidisciplinary Sci. Res. 53 (1), 98–118 (2024).

Mussett, A. E. & Khan, M. A. Looking into the Earth—An Introduction To Geological Geophysics (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Arinze, I. J., Emedo, C. O. & Ngwaka, A. C. Analysis of aeromagnetic anomalies and structural lineaments for mineral and hydrocarbon exploration in Ikom and its environs southeastern Nigeria. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 159, 284–285 (2019).

Akpan, A. E., Ebong, D. E., Ekwok, S. E. & Joseph, S. Geophysical and geological studies of the spread and industrial quality of Okurike barite deposit. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 10 (6), 566–574 (2014).

Agbi, I. & Ekwueme, B. N. Preliminary review of the geology of the hornblende biotite gneisses of Obudu plateau southeastern Nigeria. Global J. Geol. Sci. 17, 75–83 (2018).

Woakes, M., Rahaman, M. A. & Ajibade, A. C. Some metallogenetic features of the Nigerian basement. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 6 (5), 655–664 (1987).

Elkhateeb, S. O. & Eldosouky, A. M. Detection of porphyry intrusions using analytic signal (AS), Euler deconvolution, and centre for exploration targeting (CET) technique porphyry analysis at Wadi Allaqi area, South Eastern desert. Egypt. Int. J. Eng. Res. 7 (6), 471–477 (2016).

Blakeley, R. J. & Simpson, R. W. Approximating edge of source bodies from 532 magnetic or gravity anomalies. Geophysics 51, 1494–1498 (1986).

Nwankwo, L. I. Structural styles in the precambrian basement complex of southeastern Nigeria. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 53, 73–86 (2009).

Ajibade, A. C., Oyawoye, M. O. & Rahaman, M. A. Petrology of migmatites of the Obudu Plateau, Nigeria. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 56, 23–30 (2010).

Ekwok, S. E., Akpan, A. E. & Kudamnya, E. A. Exploratory mapping of structures controlling mineralization in Southeast Nigeria using high resolution airborne magnetic data. J. Afr. Earth Sci. (2020).

Ekwok, S. E., Akpan, A. E., Ebong, E. D. & Eze, O. E. Assessment of depth to magnetic sources using high resolution aeromagnetic data of some parts of the lower Benue trough and adjoining areas, Southeast Nigeria. Adv. Space Res., 67 (7), 2104 (2021).

Oha, I. A., Onuoha, K. M. & Nwegbu, A. N. Interpretation of high resolution aeromagnetic data over Southern Benue Trough, southeastern Nigeria. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 125, 369–385 (2016).

Uwiduhaye, J. D., Ngaruye, J. C. & Saibi, H. Defining potential mineral exploration from the interpretation of aeromagnetic data in Western Rwanda. Ore Geol. Rev. 128, 103927 (2021).

Abdelrahman, K., El-QassasR, A. Y. & Fnais, M. S. Geological structures controlling Au/Ba mineralization from aeromagnetic data: Harrat ad Danun Area, Saudi Arabia. Minerals 13, 866 (2023).

Ekwok, S. E., Akpan, A. E., Achadu, O. I. M. & Eze, O. E. Structural and lithological interpretation of aero-geophysical data in parts of the lower Benue trough and Obudu Plateau, Southeast Nigeria. Adv. Space Res. 68 (7), 2841–2854 (2021).

Ekwok, S. E., Akpan, A. E. & Achadu, O. I. M. Structural and lithological interpretation of aero-geophysical data in parts of the lower Benue trough and Obudu Plateau, Southeast Nigeria. Adv. Space Res. 68, 2841–2854 (2021).

Ene, E. G., Okogbue, C. O. & Dim, C. I. P. Structural styles and economic potentials of some barite deposits in the Southern Benue Trough, Nigeria. Romanian J. Earth Sci. 86 (1), 27–40 (2012).

Haruna, I. V. & Mamman, Y. D. A brief review of some metallogenetic features of uranium mineralisation in the upper Benue Trough, N.E. Nigeria. Technol. Dev. J. 9, 1–8 (2005).

Asouzu, E. C. & Onyeagocha, A. C. Geology and mineralization of the Obudu area of southeastern Nigeria. J. Afr. Earth Sc. 86, 20–34 (2013).

Obiora, D. N., Igwe, E. O. & Nwachukwu, S. O. Petrology and structural evolution of the high-grade terrain around Obudu and Oban massifs, southeastern Nigeria. J. Afr. Earth Sc. 117, 42–58 (2016).

Eseme, E. Geochemistry of Salt Springs in the Southwestern Mamfe Basin and Its Significance to Applied Sedimentology. M.Sc. Dissertation, Buea University, Buea, Cameroon, 111 (2001).

Eseme, E., Agyingi, C. M. & Foba-Tendo, J. Geochemistry and genesis of Brine emanations from cretaceous strata of the Mamfe Basin, Cameroon. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 35, 467–476 (2002).

Tijani, M. N., Loehnert, E. P. & Uma, K. O. Origin of saline groundwaters in the Ogoja area, lower Benue Trough, Nigeria. J. Afr. Earth Sc. 23 (2), 237–252 (1996).

Murat, R. C. Stratigraphy and palaeogeography of the Cretaceous and Lower Tertiary in southern Nigeria. In African Geology (Dessauvagie, T. F. J. & Whiteman, A. J.) 251–276 (1970).

Ekwok, S. E. et al. Particle swarm optimization (PSO) of high-quality magnetic data of the Obudu basement complex, Nigeria. Minerals 13 (9), 1209 (2023).

Song, H. et al. CAUM: A software for calculating and assessing chemical ages of uranium minerals. Geosci. Front. 16 (3), 102031 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their sincere appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-249), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for funding this research article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.E.E., S.E.E., C.E.T., E.I.O., A.A.O., K.A., M.S.F., P.A. and A.M.E.wrote the main manuscript text, prepared the figures, and applied methodologies. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eze, O.E., Ekwok, S.E., Thompson, C.E. et al. Deciphering aeromagnetic data for sustainable sedimentary and structural insights in Obudu Plateau, Ikom Mamfe embayment and Oban Massif, southeastern Nigeria. Sci Rep 15, 40387 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24801-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24801-2