Abstract

The Amazon forest was struck by an El Niño event with record heat and drought during the second semester 2023, and again in 2024. However, it remains unclear whether this extreme event impacted the forest understory because long-term in situ measurements are rare. Here, we present a time series of understory air temperatures over the 2014–2024 period based on a compilation of 114 ground-based measurements in the Eastern Amazon. We found that understory temperatures increased by up to 1.6 °C in 2023–2024 relative to the 2014–2022 reference period. Understory temperatures increased by 0.04 ± 0.03 °C/yr over 2014–2024, but this increasing trend was mostly driven by the 2023–2024 extreme event. For instance, hourly distributions were significantly warmer than the reference period, reaching + 25% during the 2024 wet season. Monthly mean understory air temperature ranged from 21 to 24 °C across sites, elevation being the main driver of this spatial variability. Using locally debiased ERA5-Land 2 m air temperature, we showed that forest canopies buffered monthly mean temperatures by -2.0 ± 0.5 °C and maximum temperatures by -4.6 ± 1 °C, albeit did not prevent the 2023–2024 anomaly. The observed increase by ~ 1 °C of understory air temperature in 2023–2024 relative to the 2014–2022 period constitutes a substantial perturbation of understory species’ theoretical thermal niche, particularly threatening ectotherms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Amazon tropical moist forest has recently experienced an unprecedented succession of extreme climatic events1,2,3,4,5. An exceptionally long La Niña event (2020–2022) has led to major floods of the Amazon river in 20211 and to negative temperature anomalies in northern Amazon over 2022–20232,6. In 2023 and 2024, the Amazon region experienced record breaking dry and hot conditions, with maximum air temperature anomalies up to + 3 °C relative to the 1980–2023 average, the highest since 19602,7 and the Rio Negro reaching its lowest level since 1902 (Manaus port authority). In French Guiana, the year 2024 was the warmest since 19688.

Extreme events are likely to play an important role in the functioning of tropical forest ecosystems and their wildlife9,10. Tropical forest understories have a stable microclimate, and they shelter a diversity of microhabitats, and a staggering number of arthropods, amphibians, plants and mammals11,12,13. The climatic niche of animal species is to a large extent determined by their thermal limits14,15, with a limited ability for species to adapt if shifts are abrupt16,17. Tropical ectotherms are more vulnerable to increasing temperatures than their higher latitude counterparts because their thermal niche is narrower18,19,20,21,22. Given this vulnerability, understanding whether extreme events surpass canopy buffering is essential.

Developing a causal link between macroclimatic conditions and wildlife persistence is very challenging. An explanation for this is that the connection between above-forest climatic conditions available from climate models and tropical forest understory microclimates remains poorly understood as the buffering effect of forest canopies are dynamic23,24,25,26. Over the 1990–2019 period, global mean temperature has risen by just less than 1 °C, and a recent study indicates that most tropical forest understories have already shifted to novel microclimate regimes27. However, tropical forests are severely underrepresented in direct micrometeorological observational databases28,29,30,31: only a handful of short-term and single site-based micrometeorological studies have highlighted the importance of canopy closure on understory temperature in the Amazon32,33,34,35,36. Despite recent advances on Amazonian microclimates37, there are few long-term studies38, especially in the eastern Amazon.

Here, we study the microclimate and its variation over the last decade in the understorey of four tropical forests from Eastern Amazonia. We document the temporal dynamics of air temperature in the tropical forest understory, and its local and subregional variations, exposing the assumption that tropical forests are tightly regulated thermally. We then assess the drivers of understory temperature spatial variability. Finally, we report the temperature buffering capacities of the different monitored forests. We hypothesize that:

(1) understory mean air temperature tracks seasonal and extreme events;

(2) the average buffering potential is equivalent across forest sites;

(3) the thermal response of forests to extreme events is site-specific and should be documented to understand patterns of biological diversity.

Methods

Study sites

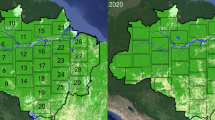

The study area covers lowland tropical moist forests located in French Guiana in the Eastern Guiana Shield, which is part of the Amazonian forest biome (Fig. 1). All four sites included in the study feature a seasonal climate driven by the latitudinal oscillations of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone. The typical wet season brings heavy rainfall up to 600 mm/month from December to July while the dry season extends from September to November with less than 50 mm/month.

Forest study sites and sensor locations. The four monitored forest sites (orange dots) extend from near the shoreline (Laussat and Paracou) to ~ 200 km inland (Itoupé). The location of Mapane and Arbocel, two forest sites which are historical microclimate references for the Guiana Shield lowland forest is shown in blue dots. The measurement points (i.e. the locations where the temperature sensors are placed) are represented by purple diamonds. The monitored area ranges from 4 km2 to 20 km2 depending on the forest site. The background elevation is provided by Mapzen and the maps were generated with QGIS 3.34.13.

The Laussat site (5°28′N 53°34′W) is a lowland moist forest on white sand, with a distinctive flora typical of this soil type39. The Paracou field station (04°15′N, 52°55′W) is a lowland moist forest on sandy-clayey soils on the coastal part of French Guiana40. The Nouragues field station (04°05′N, 52°40′W) is a lowland moist forest on sandy-clayey soils on a granitic substrate typical of the Guiana Shield41. Finally, the Itoupé site (3°01′N, 53°04′W) is a granitic outcrop of the Amazonian Park of French Guiana (Parc Amazonien de Guyane—PAG) , a protected area that covers most of the interior of French Guiana42. The Itoupé mountain spans an altitudinal range of 300–900 m, and this site has been chosen by the PAG as a reference site to track climate changes on tropical cloud mountain biome in French Guiana. Following an initial exploration in 2010, regular field trips were conducted from 2014 to 2024 and environmental monitoring was carried out by the PAG. At the Itoupé site, we stratified the study sites based on elevation: we distinguished low-elevation sites in the 400–600 m range (ITO1), mid-elevation sites in the 600–800 m range (ITO2) and high-elevation sites above 800 m in elevation (ITO3).

Field protocol

In total we collected data from 114 microclimate sensors across the four study sites, representing a total of 388 years of measurement over the 2014–2024 period (Table in SI). When a sensor failed, it was replaced by another at the same measurement point (n = 28 replacements). Thus, we considered a single time series for each measurement point. The oldest sensor was installed in January 2014, the shortest and longest monitoring lengths are 0.36 and 8.1 years respectively, and the period 2018–2024 spans the highest sampling intensity.

Two different sensors were used: the TMS sensors (n = 65, TMS3 and TMS4 models, accuracy = ± 0.5 °C)43, that measure air temperature at 15 cm aboveground every 15 to 60 min, and the U23 sensors (n = 49, accuracy = ± 0.2 °C, HOBO documentation), installed at 100 cm aboveground to avoid scatter-hoarding animals, and that measure air temperature every 30 min. Height differences did not introduce bias (see Fig. S15).

The forest understory is heterogeneous, and the variation across sensors is assumed to provide an estimate of this natural spatial variability. Since we focused our analysis on forest understory microclimate, we excluded sensors located in forest gaps, forest gap borders and open habitats. The sensors closest to a forest gap are located at ~ 20 m from the opening. We also excluded the sensors that had failed during the majority of the recording period. Finally, we did not try to correct for putative differences between sensors with and without radiation shields as all sensors were already in a shaded environment below vegetation canopies.

Acquisition time was variable across sensors and forest sites, ranging from a few months to ten years. Hence, we split the dataset into two groups of sensors according to the time period they spanned: long-term sensors monitored at least the full 2018–2024 period (seven years; n = 24); short-term sensors were those measuring shorter periods (n = 90; Table TS1 and Fig. S1). Long-term sensors were used to study the trends of local microclimate while short-term sensors provided additional information on microclimate spatial variability within the same forest site.

Raw data processing

A first order cleaning consisted in removing sensor malfunction periods. These were detected when air temperature remained constant (usually below 8 °C) over more than a day. We then removed outliers from the temperature records using a Hampel filter. Over a monthly rolling window average (avg), a data point was discarded if it was farther away from the mean than a factor 5 of the standard deviation (std). In other words, an outlier was defined as a point x for which \(\left|\frac{x-avg}{std}\right|>5\) and was removed from the time series. This threshold was defined by sensitivity analysis in order to maximize outlier removal and to minimize the dampening of natural variability. The average percentage of outliers varied between sites: 1.7% at Itoupé, 4.2% at Paracou, 6.3% at Laussat and 14.7% at Nouragues.

Sensor locations covered a large range of elevations, from sea level to 816 m asl. In order to compare forest understory responses between locations, we corrected all the data for elevation using an environmental lapse rate correction method (henceforth, ELR correction)38,44. We derived a sea level equivalent temperature (TSL) for each sensor as follows: \({T}_{SL}={T}_{S}- \Gamma *{z}_{S}\) where zS is the sensor elevation and TS is the original temperature. This linear dependence has a single parameter, Γ, the regional environmental lapse rate (rate of temperature change with elevation). We chose the most regionally relevant value of Γ (-3.8 °C/km) provided by Rozante, Ramirez, and Fernandes (2022)45 for northern Amazon. The raw time series and their equivalent at sea level is shown on Figure S2. The same ELR corrections were used to correct the macroclimate temperature at weather stations.

Statistical analyses

Temporal trends in the temperature time series were computed using the Theil-Sen slope estimates46, providing lower and upper slopes as confidence intervals.

To compare understory temperature anomalies to the macroclimate natural variability, we used the El Niño 1 + 2 index defined over the (5N-5S,150W-90W) region using the sea surface temperature from the HadISST1.1 observation dataset47.

Changes in hourly understory temperature distributions between 2023, 2024 and the 2014–2022 historical baseline were quantified using a novelty index inspired from Trew et al. (2024)27. Using a kernel density estimate, we computed the temperature distributions for the 2023 and 2024 dry (wet) seasons and compared them to the distributions yielded by 22,312 randomly sampled temperature values from the 2014–2022 dry (wet) seasons. This number of random samples (22,312) was chosen to ensure comparable sampling efforts between 2023, 2024 and the 2014–2022 period. An index was derived as 1 minus the proportion of overlap in hourly values between the 2023 (2024) and the 2014–2022 periods, calculated as:

We repeated this operation 100 times and calculated the novelty index as the mean of the 100 resulting indices. The novelty index ranges between 0 and 100 and represents the percentage of hours in the 2023 or 2024 dry (wet) season which lie outside the range of temperatures that occurred in the historical dry (wet) season climatology.

An estimation of the intra-site variability was obtained by detrending sensor time series with the monthly mean temperature trend at the corresponding site. Total variability was obtained by detrending all sensor time series with the monthly mean temperature trend of the full dataset. Finally, we computed the intersite variability as the difference between the total variability and the mean of intra-site variability.

The buffering of understory temperatures by forest canopies was characterized by computing the temperature difference, ΔT (the offset), between understory and a nearby open area chosen as a reference. In French Guiana, few open areas exist as most of the region is forested, and we could not find one for all four study sites. We therefore used the ERA5-Land 2 m-temperature hourly reanalysis as an out-of-forest macroclimate proxy. We compared this product with reference weather stations (Meteo-France) in other parts of French Guiana and found that a bias correction was needed both for the mean and the standard deviation (Fig S7 and S8). We bias-corrected the ERA5-Land 2 m temperature data by first applying an environmental lapse rate correction to account for the elevation difference between the ERA5-Land grid and the sensor locations. We then applied a mean and variance correction to remove diurnal and seasonal biases (see SI section 3 for details), and built mean and maximum monthly and hourly time series for each sensor, from which we computed the offset. ∆Tmean and ∆Tmax are the offset for the mean and the maximum (95th percentile) temperatures respectively.

For each forest site, we also computed the linear regression slope between hourly ERA5-Land data and hourly sensor data as another indicator of the capacity of the forest canopy to buffer macroclimate (ERA5-Land) temperature variations48,49. The lower the slope, the stronger the buffering.

All data analysis was conducted with Python 3.9.2 and the scripts are available for reproducibility at https://github.com/Gabriel-Hes/FGuiana_understory_temp.git. Figures 1 and 7 were generated with QGIS 3.34.13 software.

Results

A. Understory temperature extremes in 2022, 2023 and 2024

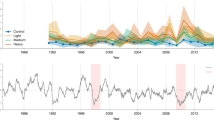

We first analyzed the composite time series for the period 2014–2024 (11 years) corresponding to sea-level monthly understory temperature (Fig. 2a). Our key findings were that (1) 2023–2024 were the warmest years, (2) the long-term trend is positive but lower than the macroclimate and (3) understory temperature was strongly linked with El Niño. In 2023 and 2024, an upward shift of between 0.7 °C and 1.6 °C of the understory temperature was observed at all sites, depending on the site and season (Fig. 2a and Fig. S13). Because the end of 2022 and early 2023 featured the lowest temperatures in the record, the year 2023 had an anomalously high seasonal amplitude of 3.1 °C.

Evolution of monthly mean (black, a), maximum and minimum (red and blue, b) understory temperature once corrected for altitude. Each line represents an individual sensor and the thick dark line is the mean. We also provide equivalent time series for long-term sensors only at each forest site in Figure S4. The Theil-Sen linear trend of + 0.037 [0.005, 0.071]°C/year is shown in light gold with an uncertainty envelope defined by the lowest and highest slopes (shaded gold).

Maximum and minimum temperatures (Fig. 2b) also reached their highest annual lows and highs in 2023 (see Fig. S4 and Fig. S5 for long-term sensors and full dataset per forest site). The warm anomaly is particularly visible on the seasonal cycle (Fig. S12): during the late months of 2023 and the early months of 2024, air temperatures exceeded all previous years for all forest sites. Over the 2014–2024 period, we measured an upward trend of + 0.037 [0.005, 0.071]°C/yr in understory temperature (Table TS2 and TS3). This signals a significant and upward shift in the understory, yet slightly slower than the regional macroclimate trend of + 0.057 [0.025, 0.09]°C/yr measured at Kourou during this period. In addition, we found that the mean understory temperature was highly correlated (r = 0.41) to the El Niño index for a 4-month lag (Fig. S17).

We also quantified how much the 2023–2024 warm anomaly has affected the average forest understory. The hourly temperature histogram differed significantly in 2023 and 2024 relative to the 2014–2022 period for both wet and dry seasons (months of May and October respectively, i.e. the peak of each season). Based on the calculation of the novelty index, October 2023 differed by 22% and October 2024 by 6% relative to the 2014–2022 period (Fig. 3a). In October 2023, average temperature was 25.7 °C, 1.2 °C above the 2014–2022 mean. The contrast was also pronounced in the wet season with a novelty index of 22% in May 2023 and 25% in May 2024 relative to the 2014–2022 period (Fig. 3b). These values suggest that roughly a quarter of the 2023–2024 wet season conditions had never occurred in the previous record. The May 2024 distribution is particularly anomalous for Nouragues and Itoupé characterized by a novelty index above 30% (Fig. S14).

Hourly temperature distribution from the full dataset in October (wet season) and May (dry season) for 2014–2022 period (black), year 2023 (red) and 2024 (green). Laussat is not accounted for in the October 2024 distribution because this period is lacking (see Fig. S7). The novelty index (i.e. the proportion of non-overlapping area between year 2023 (or 2024) and the 2014–2022 period) is 22% (6%) for October and 22% (25%) for May of year 2023 (and 2024 respectively). The colored ticks represent the mean for each distribution.

B. Spatial heterogeneity of forest understory temperatures

We found a consistent seasonal pattern of mean understory air temperature in all four forest sites (Nouragues, Paracou, Laussat and Itoupé) after applying the environmental lapse rate correction (Fig. S3 and S4). Using the uncorrected dataset over the 2014–2024 period, we found an elevational gradient of temperature equal to -3.8 ± 0.1 °C/km (Fig. 4a), consistent with the environmental lapse rate of -3.8 °C/km by Rozante, Ramirez, and Fernandes (2022)45. Hence, the understory microclimate is largely driven by the elevational gradient. The regular amplitude of seasonal variation in understory temperature was driven by the hot dry season (September–November) and the relatively colder wet season was within 2 °C for all the years prior to 2023 (September–November mean minus January–February mean = 1.36 °C for the 2014–2022 period).

Understory temperature altitudinal gradient and inter-sensor heterogeneity. (a) Monthly understory temperature for each sensor (black dots) as a function of altitude and the associated Theil-Sen slope (red line) over the 2014–2024 period. The Theil-Sen slope 95% confidence interval is shown in shaded red. For comparison, the out-of-forest environmental lapse rate (-3.82 °C/km)45 is shown in purple using the Kourou weather station as the sea-level reference (+ /- std is shown in shaded purple). (b) Distribution and (c) cumulative distribution of the detrended monthly mean (blue), maximum (95th percentile, red) and minimum (5th percentile, green) understory temperature for all sensors at sea level computed with a kernel density estimation.

We also explored the intra- and inter-site variations in temperature to understand how much one site could account for the total temperature variance once corrected for elevation. We found a total variance of 0.13 °C and an average intrasite variance of 0.09 °C thus yielding an intersite variance of 0.04 °C. This result indicates that a large part of the total temperature variability can be found over one single site. The relatively small intersite variability implies that a single site can adequately represent the region. The total variation was summarized by a distribution of the deviation (Fig. 4b and Fig. 4c). For 90% of recorded mean temperatures, we found that the deviation to the mean falls within ± 0.57 °C. In other words, the difference in monthly mean temperature between two measurement locations exceeds 0.57 °C only 10% of the time.

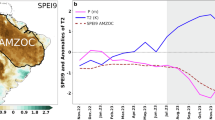

C. Stable buffering effect of forest canopies

We compared forest understory temperature to out-of-forest temperature, thus measuring the buffering effect of the canopy, ΔT. Our main observation was that buffering was insufficient to prevent the record temperature. Hourly understory temperatures were consistently below ERA5-Land air temperatures (Fig. 5), implying that forest understories were buffered most of the time. Slopes ranged from 0.31 to 0.53, confirming the strong buffering of all forest sites. Yet, we also found that understory temperatures could be amplified especially during the night (see Fig. S10 and S11) as shown by previous studies37,38.

We found that forest canopies buffered monthly mean temperatures by -2.0 ± 0.5 °C and maximum temperatures by -4.6 ± 1 °C (Fig. 6). In addition, we observed some seasonal variability with usually lower ΔTmean and ΔTmax during the dry season than the wet season, although the signal was not always consistent between years and sites. For instance, the 2023 dry season featured strong mean and maximum temperature buffering for all sites but Paracou for which we reported a buffer loss. Over the 2016–2024 period, we also found a significant increasing trend in ΔTmean and ΔTmax for Paracou only (0.06 [0.04, 0.08]°C/year and 0.1 [0.08, 0.12]°C/year respectively, Table TS5) suggesting a lowered capacity of this forest canopy to act as a buffer against maximum temperatures.

Discussion

Here, we present an eleven-year record of understory temperature across four moist tropical forest sites of the Guiana Shield allowing us to quantify regional and local heterogeneity and to document long-term trends.

The 2023–2024 microclimate anomaly

We report a striking temperature increase in mean, minimum and maximum understory temperatures at all four study sites in 2023 and 2024. This back-to-back temperature anomaly follows an unusually cold episode at the end of 2022 corresponding to La Niña 2022–2023 2,50. Forest understory temperatures were also different from the 2014–2022 period as indicated by the novelty index (Fig. 3). Together these findings show that the large temperature anomalies in the macroclimate translate to large anomalies in the forest understory. In other words, the average buffering capacity of east amazonian forests is not much altered and rather increased during extreme events. In addition, the monthly soil water content measured by the flux tower in Paracou forest reveals an anomalously low moisture over 2023–2024 (Fig. S16) highlighting a severe drought. Here, we demonstrate that the exceptional 2023–2024 drought event, driven by global climate change51, had major consequences on the forest understory thermal environment.

The impact of the 2023 El Niño event on understory temperatures was especially massive, shifting the mean seasonal cycle by roughly 1 °C from September 2023 to December 2024. This anomaly makes the 2023–2024 event unique during our study period, even compared to the 2015–2016 El Niño-induced drought at the beginning of our record, which had caused the most severe meteorological drought over the 2000–2019 period52. The 2023 El Niño drought yielded negative rainfall anomalies over southwestern Amazonia during November 2022–February 2023 and over northern Amazonia during June–September 2023 season. Overall, the 2023 macroclimate record warming focused on the northern Amazon including the present study areas2. Northeastern Amazon was also shown to be among the amazonian regions with the most rapid warming and the strongest temperature sensitivity to El Niño53,54. Therefore, our results should be representative of 2023 El Niño’s most severe impacts on the Amazon moist forest understory microclimate.

Tropical forests may be approaching a tipping point in metabolic function9, and the 2023–2024 event may be an early warning signal for such a step change for the Amazon.

The massive increase in the understory temperature may have profound implications for local fauna and flora especially when combined with a drought. Such understory extreme events could also disturb multiple aspects of forest dynamics (e.g. recruitment, growth and mortality) and attention should be given to post-disturbance recovery55.

Rapid shifts in the forest understory climate would have direct implications for the wildlife (Fig. 7). Tropical amphibian populations are known to be restricted to narrow thermal and hygrometric conditions56,57. For instance, the rare Pristimantis espedeus, an arboreal frog endemic to the Guiana Shield with most populations known in French Guiana to date, was only found in forests from 200 to 700 m elevation on massifs > 400 m 56. Because Pristimantis espedeus is particularly sensitive to hot and dry conditions and only present on isolated mountains across the Guiana Shield, there is a possibility of extinction by 2070 because of climate change57. Here, our results may be used to map the changes in Pristimantis espedeus potential spatial niche linked to thermal suitability for the 2023 dry season compared to the 2014–2022 dry season climatology (Fig. 7). Using the understory temperatures from Itoupé, we found a local linear relationship between temperature and altitude during the 2014–2022 dry seasons allowing to define a temperature range for the elevational range (200–700 m) where Pristimantis espedeus was found. Our data shows that during the 2023 dry season, this same temperature range was observed at higher altitudes (440–830 m), such that Pristimantis espedeus was theoretically unable to persist in the lowland forests. This shift during the 2023 dry season also resulted in a significant reduction (roughly 80% surface loss) of the suitable habitats area for that species (Fig. 7). Although this single example cannot be generalised to all tropical forest understory species, it illustrates how the 2023–2024 warm anomaly could have affected the most thermosensitive ones. Regular field data are needed to estimate whether the low altitudinal bound of P. espedeus on Itoupé mountain is stable over years. In addition, integrating extreme climate events10 and embracing spatiotemporal gradients simultaneously and at different scales (microhabitat changes, elevational changes)58 may help to understand and predict distribution shifts of species on the move.

Theoretical thermal niche of Pristimantis espedeus at Itoupé forest during the dry season (represented by September and October months) for the 2014–2022 climatology (a) and for the year 2023 (b). The theoretical thermal niche is delimited by the range of maximum temperatures observed for the altitudes of occurrence during the 2014–2022 mean and is represented by shaded colors from blue to red. The area outside the theoretical thermal niche is in purple. Sensor location is shown with white dots. The terrain model used to compute the theoretical thermal niche was provided by Mapzen and the maps were generated with QGIS 3.34.13.

Excluding the 2023–2024 exceptional years, the understory temperatures are stable with limited seasonal variation (~ 2 °C) in agreement with Tymen et al. (2017)36 and as predicted for thermally stable tropical rain forests. We did find some seasonal variability, the highest temperatures being during the dry season when there is less potential for evapotranspiration. In addition, we explored the fine-scale variation of monthly temperature within and across forest sites, and found that the forest understory is strongly regulated and fairly homogeneous.

Along with regional macroclimate, we found that elevation was a strong driver of forest microclimate. We measured an average understory altitudinal gradient of -3.84 [-3.93,-3.75]°C/km subject to seasonal variations. This result is consistent with the lapse rate found by Rozante, Ramirez, and Fernandes (2022)45 outside forests, thereby suggesting that forest canopies do not impact the yearly mean temperature dependence to elevation.

We observed that all forests had a strong buffering effect, dampening mean temperatures by roughly 2 °C. This temperature dampening is larger than for higher latitude forests25 and falls within the range of previous estimations for global tropical forests25,37. The maximum temperature buffering is also consistent with that found by De Lombaerde et al., (2022)25. However, our study suggests a larger buffering than observations in northern Amazon37 and modeling studies for tropical forests26,59. Such a discrepancy could be due to the longer temporal coverage of the present analysis, the difference in macroclimate proxy and the lack of comprehensive model validation.

We observed a consistent but minor seasonal pattern in the buffering of mean temperature across sites with larger temperature damping during the dry season (Fig. S11) although this pattern was reversed in Paracou in 2023 and 2024 (Fig. 6a). This result is in line with previous findings by Ismaeel et al., (2024) but differs from the global tropical seasonal cycle reported by Zhang et al., (2023)59 featuring a weaker buffering during the warm season as compared to the cold season. This discrepancy can be explained by the fact that the offset seasonal cycle differs between continents as shown by Ismaeel et al., (2024)37. In addition, we showed that the maximum temperatures were regularly amplified mostly during the night in some forests. This result is consistent with the nighttime positive temperature offsets already reported in some tropical forests37.

Over the 2014–2024 period, the mean understory temperature trend increased less than the temperature reference in Kourou weather station thus suggesting a decoupling of understory microclimate and macroclimate leading to more buffering as in Hes et al. (2024)26. However, this is not confirmed by the mean temperature offset time series built with ERA5-Land for which we found non-significant trends for most forest sites and a positive trend for Paracou over 2016–2024 meaning a possible loss of the buffer. Zhang et al., (2023)59 also showed a decreasing buffering effect in tropical forests over 2003–2011. Conclusions about long-term changes in the canopy buffering are not possible due to the limited duration of the record.

Challenging definition of macroclimate

Our study highlights the challenges to define a tropical macroclimate reference in the Amazon forest. The temperature offset is very sensitive to the choice of macroclimate reference so we insist on the importance of choosing the most locally relevant reference data61.

The most straightforward option for comparing climate out of forests and within forests would be to use the nearest out-of-forest weather station60,61. However, the majority of Amazon forest sites are far from existing weather stations. If the forest site is equipped with a local weather station, it is still not always representative of the free air temperature. Weather stations located in small clearings provide a ‘forest edge’ microclimate rather than an open-land macroclimate. Similarly, the above canopy temperature measured from a flux tower is not equivalent to an open-land measurement because it is higher in altitude and affected by the underlying forest boundary condition (see Fig. S18). Such estimation should rather be considered as an ‘above canopy’ microclimate than as an open-land macroclimate. Macroclimate reanalyses (as ERA5-Land used here) or remote sensing products also provide a gridded macroclimate proxy but can be biased (see SI section “Results” for details). Therefore, choosing locally relevant macroclimate references is crucial to interpret temperature offsets. In general, increasing the network of long-term out-of-forest inland weather stations would help to provide a finer description of the effects of forests on understory microclimate.

Limits and future perspectives

In this work, we report that the 2023–2024 period featured strong positive understory temperature anomalies with respect to the past decadal record, what could be called an “understory extreme event”. The limits to this study can serve as prisms for future investigations. First, the present record is not long enough to detect trends that could be related to climate change. For instance, the opposition between the positive trend in ΔTmax observed at one forest site and the negative ΔTmax trend modeled for tropical forests in a warming climate in Hes et al. (2024)26 suggests an inconsistency between models and empirical results and resolving it would benefit from longer site-based micrometeorological observations. Second, we demonstrated that the effect of elevation was comparable below and above the canopy, yet one would expect that the presence of forests might change the environmental lapse rate seasonally. Because forests transpire, they could increase local air moisture and therefore increase thermal inertia of the air which in turn controls the environmental lapse rate. This hypothesis would deserve further scrutiny. Third, the significant residual temperature variability between sensors once corrected for altitude calls for a reanalysis of the local drivers of understory microclimate. We hypothesize that such drivers may include canopy dynamics, forest structure, soil composition, water table depth and correlations between light, temperature (air and soil) and relative humidity36,39. Understanding local drivers can help to predict microclimate and forest dynamic feedback loops and to map finer changes in species thermal niches.

Conclusions

Our study provides the first decadal time series of tropical understory air temperature based on East Amazonian rain forest sites. We report a ~ 1.5 year-long abrupt shift of + [0.7–1.6]°C of the seasonal cycle during the 2023–2024 El Niño event representing a clear anomaly relative to the full record. This understory extreme event may increase the vulnerability of thermosensitive species by reducing the range of suitable habitats. Continuous monitoring of tropical forest microclimate is needed to detect changes in the buffering and anticipate consequences on the understory wildlife.

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly available. Understory temperature data are available at https://zenodo.org/records/15131473, weather station data are available at https://meteo.data.gouv.fr/datasets/donnees-climatologiques-de-base-horaires/ data and ERA5-Land are available at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-land. The code for data analysis supporting the present study is provided at https://github.com/Gabriel-Hes/FGuiana_understory_temp.git

References

Espinoza, J.-C., Marengo, J. A., Schongart, J. & Jimenez, J. C. The new historical flood of 2021 in the Amazon River compared to major floods of the 21st century: Atmospheric features in the context of the intensification of floods. Weather Climate Extremes 35, 100406 (2022).

Espinoza, J.-C. et al. The new record of drought and warmth in the Amazon in 2023 related to regional and global climatic features. Sci. Rep. 14, 8107 (2024).

Marengo, J. Review Extreme seasonal droughts and floods in Amazonia: causes, trends and impacts. Int. J. Climatology 36, (2015).

Meunier, F. et al. Intact Amazon forests hit a record low gross primary productivity level in 2023-2024. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4161696/v1 (2024).

Tao, S. et al. Increasing and widespread vulnerability of intact tropical rainforests to repeated droughts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2116626119 (2022).

Meteo France Guyane. Une phase La Niña qui perdure encore en début d’année. https://meteofrance.gf/fr/actualites/une-phase-la-nina-qui-perdure-encore-en-debut-dannee (2022).

Maciel, D. A. et al. Sentinel-1 data reveals unprecedented reduction of open water extent due to 2023–2024 drought in the central Amazon basin. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 124034 (2024).

Meteo France Guyane. Bulletin climatique annuel 2024. https://meteofrance.gf/fr/climat/bulletin-climatique-annuel-2024 (2025).

Doughty, C. E. et al. Tropical forests are approaching critical temperature thresholds. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06391-z (2023).

Soifer, L. G. et al. Extreme events drive rapid and dynamic range fluctuations. Trends Ecol. Evol. 40, 862–873 (2025).

de Souza Amorim, D. et al. Vertical stratification of insect abundance and species richness in an Amazonian tropical forest. Sci Rep 12, 1734 (2022).

Pillay, R. et al. Tropical forests are home to over half of the world’s vertebrate species. Front. Ecol. Environ. 20, 10–15 (2022).

Basham, E. W., Baecher, J. A., Klinges, D. H. & Scheffers, B. R. Vertical stratification patterns of tropical forest vertebrates: a meta-analysis. Biol. Rev. 98, 99–114 (2023).

Deutsch, C. A. et al. Impacts of climate warming on terrestrial ectotherms across latitude. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 6668–6672 (2008).

Harvey, J. A. et al. Scientists’ warning on climate change and insects. Ecol. Monogr. 93, e1553 (2023).

Hoffmann, A. A. & Sgrò, C. M. Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature 470, 479–485 (2011).

Scheffers, B. R. et al. The broad footprint of climate change from genes to biomes to people. Science 354, aaf7671 (2016).

Araújo, M. B. et al. Heat freezes niche evolution. Ecol. Lett. 16, 1206–1219 (2013).

Basset, Y. et al. Arthropod Distribution in a Tropical Rainforest: Tackling a Four Dimensional Puzzle. PLoS ONE 10, e0144110 (2015).

Bennett, J. M. et al. The evolution of critical thermal limits of life on Earth. Nat. Commun. 12, 1198 (2021).

Huey, R. B. et al. Why tropical forest lizards are vulnerable to climate warming. Proc. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 276, 1939–1948 (2009).

Tewksbury, J. J., Huey, R. B. & Deutsch, C. A. Putting the Heat on Tropical Animals. Science 320, 1296–1297 (2008).

De Frenne, P. et al. Global buffering of temperatures under forest canopies. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 744–749 (2019).

De Frenne, P. et al. Forest microclimates and climate change: Importance, drivers and future research agenda. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 2279–2297 (2021).

De Lombaerde, E. et al. Maintaining forest cover to enhance temperature buffering under future climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 810, 151338 (2022).

Hes, G. et al. Projecting future forest microclimate using a land surface model. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 024030 (2024).

Trew, B. T. et al. Novel temperatures are already widespread beneath the world’s tropical forest canopies. Nat. Clim. Chang. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02031-0 (2024).

Antão, L. H. et al. Temperature-related biodiversity change across temperate marine and terrestrial systems. Nat Ecol Evol 4, 927–933 (2020).

Cusack, D. F. et al. Global change effects on humid tropical forests: Evidence for biogeochemical and biodiversity shifts at an ecosystem scale. Rev. Geophys. 54, 523–610 (2016).

Lembrechts, J. J. et al. SoilTemp: A global database of near-surface temperature. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 6616–6629 (2020).

Kemppinen, J. et al. Microclimate, an important part of ecology and biogeography. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 33, e13834 (2024).

Hales, W. B. Micrometeorology in the Tropics. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 30, 124–137 (1949).

Schulz, J. P. Ecological studies on rain forest in Northern Suriname. Mededelingen van het Botanisch Museum en Herbarium van de Rijksuniversiteit te Utrecht 163, 1–267 (1960).

Finkelstein, D. Evolution comparée des microclimats en coupe rase, sous recrû naturel et sous forêt primaire sur la parcelle Arbocel. Bull. Liaison Ecerex 19–32 (1982).

Freiberg, M. Spatial and Temporal Pattern of Temperature and Humidity of a Tropical Premontane Rain Forest Tree in Costa Rica. Selbyana 18, 77–84 (1997).

Tymen, B. et al. Quantifying micro-environmental variation in tropical rainforest understory at landscape scale by combining airborne LiDAR scanning and a sensor network. Ann. For. Sci. 74, 32 (2017).

Ismaeel, A. et al. Patterns of tropical forest understory temperatures. Nat Commun 15, 549 (2024).

Newell, F. L., Ausprey, I. J. & Robinson, S. K. Spatiotemporal climate variability in the Andes of northern Peru: Evaluation of gridded datasets to describe cloud forest microclimate and local rainfall. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 5892–5915 (2022).

Baraloto, C. & Couteron, P. Fine-scale Microhabitat Heterogeneity in a French Guianan Forest. Biotropica 42, 420–428 (2010).

Gourlet-Fleury, S., Guehl, J.-M. J.-M. & Laroussinie, O. Ecology and Management of a Neotropical Rainforest. Lessons Drawn from Paracou, a Long-Term Experimental Research Site in French Guiana. (Elsevier, 2004).

Bongers, F., Charles-Dominique, P., Forget, P.-M. & Théry, M. Nouragues: Dynamics and Plant-Animal Interactions in a Neotropical Rainforest. vol. 80 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Fichaux, M. et al. Environmental determinants of leaf litter ant community composition along an elevational gradient. Biotropica 53, 97–109 (2021).

Wild, J. et al. Climate at ecologically relevant scales: A new temperature and soil moisture logger for long-term microclimate measurement. Agric. For. Meteorol. 268, 40–47 (2019).

Trew, B. T. & Maclean, I. M. D. Vulnerability of global biodiversity hotspots to climate change. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 30, 768–783 (2021).

Rozante, J. R., Ramirez, E. & de Fernandes, A. A newly developed South American Mapping of Temperature with estimated lapse rate corrections. Int. J. Climatology 42, 2135–2152 (2022).

Almazroui, M. & Şen, Z. Trend Analyses Methodologies in Hydro-meteorological Records. Earth Syst Environ 4, 713–738 (2020).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 2002JD002670 (2003).

Ewers, R. M. & Banks-Leite, C. Fragmentation Impairs the Microclimate Buffering Effect of Tropical Forests. PLoS ONE 8, e58093 (2013).

Gril, E. et al. Slope and equilibrium: A parsimonious and flexible approach to model microclimate. Methods Ecol. Evol. 14, 885–897 (2023).

Mamani, L. et al. Extreme droughts in the Amazon Basin during cyclic ENSO events coupled with Indian Ocean Dipole modes and Tropical North Atlantic warming. Sci. Total Environ. 963, 178536 (2025).

Clarke, B. et al. Climate change, not El Niño, main driver of exceptional drought in highly vulnerable Amazon River Basin. (2024).

She, X. et al. Varied responses of Amazon forests to the 2005, 2010, and 2015/2016 droughts inferred from multi-source satellite data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 353, 110051 (2024).

Malhi, Y. & Wright, J. Spatial patterns and recent trends in the climate of tropical rainforest regions. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 359, 311–329 (2004).

Jiménez-Muñoz, J. C. et al. Record-breaking warming and extreme drought in the Amazon rainforest during the course of El Niño 2015–2016. Sci Rep 6, 33130 (2016).

Köpp Hollunder, R., Garbin, M. L., Rubio Scarano, F. & Mariotte, P. Regional and local determinants of drought resilience in tropical forests. Ecol. Evol. 12, e8943 (2022).

Fouquet, A. et al. A new species of the genus Pristimantis (Amphibia, Craugastoridae) associated with the moderately evelated massifs of French Guiana. Zootaxa 3750, (2013).

Courtois, E. A. et al. Taking the lead on climate change: modelling and monitoring the fate of an Amazonian frog. Oryx 50, 450–459 (2016).

Fredston, A. L. et al. Reimagining species on the move across space and time. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 0, (2025).

Zhang, C. et al. Seasonal and long-term dynamics in forest microclimate effects: global pattern and mechanism. npj Clim Atmos Sci 6, 1–12 (2023).

Gril, E. et al. Using airborne LiDAR to map forest microclimate temperature buffering or amplification. Remote Sens. Environ. 298, 113820 (2023).

De Frenne, P. et al. Ten practical guidelines for microclimate research in terrestrial ecosystems. Methods Ecol Evol 16, 269–294 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank the many people involved in fieldwork and in supporting the monitoring of forest microclimate. We are especially grateful to Hélène Delvaux for support at Parc Amazonien de Guyane and Lore T. Verryckt for sharing data. We warmly thank Rosie A. Fisher, Raphaël Garisoain, Romain Bertrand and Isabelle Maréchaux for insightful discussions of the results. We acknowledge support from the CNRS Nouragues Ecological Research Station which benefits from “France 2030” and “Investissement d’Avenir” grants managed by Agence Nationale de la Recherche (AnaEE France ANR-24-INBS-0001; Labex CEBA ANR-10-LABX-25-01). We also acknowledge funding from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Project MaCCmic ANR-21-CE32-0012 and Project ALT ANR-21-CE32-0009), from the Parc Amazonien de Guyane (PAG) and from the French ministry of higher education and research providing a doctoral fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Gabriel Hes: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; Vincyane Badouard: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing; Benoit Burban: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing; Jocelyn Cazal: data curation, investigation; Elodie A. Courtois: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing; Géraldine Derroire: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing; Léa Francoise: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing; Jean-Yves Goret: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing; Ariane Mirabel: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing; Petrus Naisso: data curation, investigation; Jérôme Ogée: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing, supervision and funding acquisition; Laetitia Proux: data curation, investigation; Elodie Schloesing: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing; Sylvain Schmitt: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing; Giacomo Sellan: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing; Clément Stahl: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing; Jérôme Chave: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing, supervision and funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author(s) declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hes, G., Badouard, V., Burban, B. et al. East Amazon forest understory temperatures reached a record high in 2023–2024. Sci Rep 15, 43423 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24810-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24810-1