Abstract

Occupational stress represents a substantial health concern. This study investigated the immediate psychophysiological effects of light-guided resonant breathing (RB) on stress recovery following standardized laboratory stressors in a simulated office environment. Eighty healthy university students participated in a controlled laboratory crossover study. After stress induction via a modified cold pressor test, participants were randomized to either 5-minute light-guided RB or passive rest. Following an 18-minute paced serial addition test for cognitive stress induction, recovery interventions were reversed. Primary outcomes included heart rate variability (root mean square of successive differences, RMSSD), heart rate, and self-reported stress and strain. The stress induction procedures triggered distinct psychophysiological stress responses patterns. RB significantly increased RMSSD during recovery after both stressors (large effect sizes) and was rated as more enjoyable than passive rest. Following cognitive stress, RB additionally reduced subjective strain and was perceived as more effective. Light-guided RB effectively promoted stress recovery, with particularly pronounced benefits following cognitive stress. By revealing distinct psychophysiological recovery mechanisms across stressor types, this study provides novel theoretical insights into autonomic recovery specificity. High participant enjoyment ratings further support the potential of RB for occupational implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stress is defined as a psychological, physiological, or behavioral response to perceived threats that exceed individual coping capacity1. Work-related stress represents a substantial proportion of the overall stress burden2,3, with computer-based work emerging as a significant contributor to occupational stress in the digital era4.

To address work-related stress, several stress management interventions have been developed5. Besides others, individual-level interventions focus on improving personal coping mechanisms6. Research indicates that these interventions can effectively reduce stress symptoms in the short to medium term, with some effects persisting for up to a year post-intervention7,8. Among these interventions, slow breathing (SB) has been shown to be a simple yet effective stress-reducing technique9. This practice involves deliberately reducing breathing rates to approximately six breaths per minute, which is significantly lower than normal breathing rates of 12 to 20 breaths per minute10. Research indicates that SB acutely activates the parasympathetic nervous system, evidenced by increased heart rate variability (HRV)11, and decreases blood pressure and cortisol levels, while also improving mood12. Despite these benefits, most SB intervention research has focused on stress-reducing effects under resting conditions13,14,15. Additional research has suggested that even single sessions of SB may exert acute carry-over effects on executive function and attention regulation16,17,18,19. However, only two studies have investigated the acute stress recovery effects of SB interventions under controlled laboratory conditions using validated stress induction procedures and fixed breathing rates of 6 breaths per minute20,21, thus leaving a gap in understanding its acute stress recovery effects.

To address this research gap and leverage the potential of SB, we developed a dynamic indicator light integrated into a computer workstation that functions as a visual pacemaker to guide users in reducing their breathing rate. The indicator light features individual LEDs that switch on sequentially to create a running light effect. This approach represents a novel application of visual light interventions, which contrasts with previous non-visual light research during daytime, which has focused on increasing alertness and cognitive performance parameters22.

To enhance the effectiveness of SB in this study, individual breathing rates were adapted to the resonant breathing (RB) rate of each study participant, a technique designed to maximize HRV and more effectively activate the parasympathetic nervous system23. Healthy young adults were exposed to two stress induction procedures that generated acute psychophysiological stress reactions. After each stress induction, participants either engaged in RB or relaxed without specific instructions (control condition). This study protocol aimed to test the following three hypotheses:

(H1) the RB intervention induces a more pronounced cardiac stress recovery response than standard rest, as indicated by increased HRV and decreased heart rate after both stress induction procedures;

(H2) study participants rate the RB intervention as more effective for stress reduction compared to the control condition; and.

(H3) study participants perceive RB as a more useful stress recovery method compared to the control condition.

Methods

Study participants

Eighty university students were recruited via institutional email and social media platforms. Inclusion criteria included the absence of current somatic or mental health conditions and no medication use except for contraception. Participants completed the World Health Organization Quality of Life – Short Form24 (WHOQOL-BREF) to assess physical, psychological, social, and environmental health domains. Color vision was assessed using an online Ishihara Color Blind Test (https://www.colorlitelens.com/ishihara-test.html). Sample size was determined through power analysis (see Supplementary Materials S1).

Acute stress induction procedures

Two complementary stress induction protocols were employed to examine stress recovery across different stressor modalities.

The first protocol utilized an adapted version of the Socially Evaluated Cold Pressor Test (hereinafter called mCPT), a validated and efficient experimental paradigm combining physical stress (3-minute cold water immersion) with social-evaluative threat25. To enhance ecological validity and better simulate workplace stress, a competitive and financial incentive component was incorporated instead of the social-threat component: same-sex participant pairs (controlling for sex differences in pain tolerance) performed the water immersion simultaneously, with €5 being awarded for either outlasting their peer or completing the full 3-minute duration. For this protocol, cold water (0.5–1 °C) was maintained in insulated containers (34 × 20 × 15 cm, 5 L capacity) using ice. Given the recent popularity of ice bathing, participants were screened for prior ice bathing experience during enrollment.

The Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task - Computerized (PASAT-C) is a validated tool for inducing cognitive load and autonomic activation26,27. During the 18-minute task, participants viewed sequential single digits (1–9) on a black screen and clicked corresponding response boxes to indicate the sum of the last two presented digits (see Supplementary Materials Figure S1). Three progressive difficulty levels featured decreasing presentation intervals (level 1: 3 s for 3 min; level 2: 2 s for 5 min; level 3: 1.5 s for 10 min). Incorrect responses triggered aversive error tones (100 ms noise burst), with additional random error tones presented during level 3. The PASAT-C was retrieved from the Inquisit 6 library (https://www.millisecond.com/).

Outcome measures

Cardiovascular stress and recovery responses

Heart rate variability (HRV) reflects the body’s capacity to adapt to physical and psychological challenges through autonomic nervous system regulation. The parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) facilitates relaxation by decreasing heart rate (HR), whereas the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) increases HR during stress28. Higher HRV correlates with greater stress resilience, improved emotion regulation, and enhanced cognitive functioning23, while low HRV is associated with stress, rumination, and mood disorders10.

In this study, HR and RMSSD were utilized as indicators of PNS activation29,30 and self-regulatory capacity31. Accordingly, interbeat intervals (IBI) were continuously recorded using a validated Polar H10 chest belt (Polar Electro, Finland)32. Data preprocessing excluded artifacts defined as IBIs > 1500 ms, < 400 ms, or > 40% difference in consecutive IBIs, ensuring reliable HR and RMSSD calculations33. To account for adaptation effects, the first minute of IBI recordings during stress induction and recovery periods was excluded. From these data, individual root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) was calculated using sliding 1-minute windows (separated by 2-second intervals), which were then averaged to provide a robust estimate of individual RMSSD. Individual HR scores were derived by averaging IBI data, again with exclusion of the first minute of recordings.

For temporal dynamics analysis during stress induction and recovery, individual RMSSD scores were calculated using sliding 1-minute windows (separated by 2-second intervals) and averaged at each time point across participants within each condition34. Individual HR data were resampled to 0.5 Hz (to match the 2-second sliding interval procedure) and averaged across participants per condition. Both procedures incorporated IBI data from recording onset (without removing the first minute IBI data) to capture cardiovascular responses during the complete experimental procedures.

Subjective stress and strain scales

Perceived stress during and after both stress protocols was assessed using a single-item pictorial Likert scale35 (hereinafter called stress scale) with six response options ranging from 0 (no stress) to 5 (maximum stress). Each response option was visualized with corresponding emoji faces (see Supplementary Materials Figure S2). Single-item stress scales are validated measures of subjective stress (e.g35,36.,, and emoji-based scales are frequently employed in pain research37.

Current psychological and physiological strain was measured using the Short Form Questionnaire on Current Strain (KAB38,, a 6-item self-report instrument designed for rapid, repeated assessment of workload and stress in occupational settings. The KAB comprises six bipolar adjective pairs representing contrasting states: tense- relaxed, anxious-dissolved, worried-unconcerned, restless-relaxed, skeptical-confident, and uncomfortable-comfortable. Participants rated their current state on 6-point Likert scales (0–5). Total scores were calculated by averaging all items, with higher scores indicating greater strain. Internal consistency of the KAB was moderate to high (Cronbach α: 0.62–0.73).

User experience scale

User experience with the two stress recovery interventions was evaluated using three items from the short version of the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ-S39,. The selected items assessed usefulness (inefficient-efficient), ease of use (complicated-easy), and enjoyment (boring-exiting). Participants rated each item on a 7-point semantic differential scale (0–6). Each item was analyzed separately.

Stress recovery interventions

A light-based prototype was developed for RB at computer workstations. The device comprised two RGB LED strips (Adafruit NeoPixel; https://www.adafruit.com/product/1507) with diffusers, housed in 3D-printed enclosures and mounted vertically on both sides of a computer monitor. Control logic was implemented using a Raspberry Pi Zero WH. LED control utilized the Adafruit Circuit Python library to generate synchronous, vertically moving lights that guided breathing patterns: upward motion indicated inhalation, while downward motion signaled exhalation (see Supplementary Materials Figure S3). The visual pacemaker maintained equal inhalation/exhalation ratios without breathing pauses. While targeting recommended RB rates of 4, 6, and 8 breaths per minute40, technical limitations resulted in actual frequencies of 3.6, 5.6, and 8.2 breaths per minute. Participants could personalize the visual pacemaker by selecting their preferred color (purple, blue, green, yellow, orange, or red) and brightness at the study’s outset.

The pacemaker was designed to minimize non-image forming light effects. Across all colors, it generated a maximum of 9 melanopic equivalent daylight illuminance (CIE S 026, 2018) when measured at eye level in a seated position. This intensity falls below the threshold for affecting alertness or sleep41. The control condition involved quiet sitting with the prototype deactivated. Participants were instructed to relax as they normally would, without additional guidance.

Laboratory conditions were standardized in an 80 m² space with two computer workstations. Closed blinds eliminated natural light, while artificial ceiling lighting provided 500 lx desk illuminance at 4000 K, complying with office lighting standards (EN 12464-1). The research prototype contributed an additional 8 lx horizontal illuminance, thus maintaining consistent lighting conditions throughout testing.

Study protocol

Participants first selected their preferred color and brightness level for the visual pacemaker, with settings stored for subsequent breathing interventions. Individual RB rates were then determined by guiding participants in a seated position through three breathing frequencies (3.6, 5.6, and 8.2 breaths per minute) for 2.5 min each using the visual pacemaker, separated by 5-minute breaks. The breathing rate yielding the highest RMSSD was selected as the individual RB rate. This procedure lasted 20 min. Participants were not assessed for coffee intake, smoking status, energy drink consumption, or physical activity prior to the experiment.

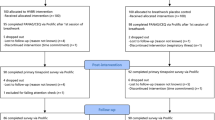

Following RB calibration, participants were randomly assigned (stratified by sex) to two groups (hereinafter called ‘group 1’ and ‘group 2’, see Fig. 1). All participants then completed the 3-minute mCPT protocol. Group 1 subsequently performed the 5-minute RB stress recovery intervention while group 2 engaged in self-directed relaxation (control condition). After a 5-minute break, during which participants were instructed to remain seated and refrain from drinking, smoking, eating, or using smartphones, all participants underwent the 18-minute cognitive stress induction (PASAT-C). Subsequently, the stress recovery interventions were reversed: group 1 received the control condition while group 2 performed RB.

Subjective stress (stress scale) was assessed immediately before and after each stress induction and following recovery periods. Psychological and physiological strain (KAB) were measured after each stress recovery period. Additionally, user experience was evaluated using three items from the UEQ-S. Interbeat interval (IBI) data were continuously recorded throughout the study using the Polar H10 chest belt.

The study was approved by the University of Innsbruck Ethics Committee (No. 93/2023). Participants provided written informed consent and received €45 compensation, with an additional €5 for mCPT completion or superior performance. Data collection took place during morning (9–12 am) or afternoon (2–5 pm) sessions between December 2023 and April 2024.

Statistics

Demographic and health parameters were compared between groups using independent samples t-tests and Fisher exact tests.

Changes in subjective stress (stress scale) and physiological parameters (RMSSD, HR) were analyzed using mixed analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with time as a within-subject factor and intervention as a between-subject factor. Significant interactions were followed by post-hoc tests with Bonferroni correction. Differences between the stress recovery interventions in psychological and physiological strain (KAB) and user experiences (three items of the UEQ-S) were examined using independent samples t-tests.

As data collection occurred during both morning and afternoon sessions, we conducted additional ANOVAs to examine time-of-day-specific intervention effects. The time of day factor was not statistically significant (see Supplementary Materials Table S1, Table S2, and Table S3).

Temporal HR and RMSSD dynamics were visualized through time course plots showing means with 95% confidence intervals. Point-by-point comparisons assessed intervention differences during stress recovery at 2-second intervals. Differences were identified as significant when one intervention’s mean fell outside the other’s 95% confidence interval (as indicated by horizontal lines).

Data are presented as mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD). Figures display means with 95% confidence intervals (CI). All tests were two-tailed (α = 0.05). Effect sizes are reported as partial eta squared (ηp2) for ANOVAs and Cohen’s d for t-tests.

Results

Study sample

Eighty students participated with an equal gender distribution (mean age = 22.8 years). The majority were psychology students (N = 57; 71%) and enrolled in undergraduate programs (N = 62; 78%). Participants demonstrated normal color perception (Ishihara test) and good health status (WHOQOL-BREF). For 71% of participants (N = 57), the personalized breathing rate was 5.6 breaths per minute. Preferred visual pacemaker settings included dimmed orange (35%), blue (20%), and green (20%) lighting (see Table 1). No significant differences were observed between groups for demographics or intervention parameters (all p >.05; see Table 1).

Stress induction 1 (mCPT)

Effectiveness of mCPT

Four participants (5%) discontinued the mCPT before the 3-minute threshold (stopping at 73, 91, 97, and 160 s). The mCPT did not significantly change subjective stress (stress scale) ratings (pre: 1.4 ± 1.0; post: 1.3 ± 1.0), t(79) = 0.803, p =.424, d = 0.09. Physiological analyses revealed that HR increased initially (from 94.8 ± 16.4 beats per minute to 98.7 ± 17.4 beats per minute) within 15 s, then decreased over 120 s, stabilizing at 85.7 ± 15.4 beats per minute until protocol completion (Fig. 2A). RMSSD increased during the first 120 s (from 30.4 ± 14.5 ms to 41.6 ± 25.0 ms) and maintained this level until the end of the stress induction procedure (Fig. 2B).

Prior ice-bathing experience did not influence physiological responses to the mCPT (see Supplementary Materials S2).

Stress recovery after mCPT

A mixed ANOVA revealed no significant time x intervention interaction for subjective stress (F(1,78) = 0.017, p =.898, ηp2 = 0.00) or main effect of intervention (F(1,78) = 1.637, p =.204, ηp2 = 0.02). However, the factor time showed a significant main effect with a large effect size, indicating decreased subjective stress during recovery for both interventions (F(1,78) = 14.023, p <.001, ηp2 = 0.15). Subjective strain (KAB), measured once after recovery, did not differ between the two stress recovery interventions (t(78) = 0.213, p =.645, d = 0.08). Means and standard deviations for the stress scale and KAB are shown in Supplementary Materials Table S4.

For RMSSD, a significant interaction effect with a large effect size was observed (F(1,78) = 24.193, p <.001, ηp2 = 0.24). Post-hoc analyses revealed significant RMSSD increases under RB (p <.001) and significant differences in RMSSD scores during recovery between the two interventions (p =.005); see Fig. 3. HR showed no significant interaction (F(1, 78) = 0.148; p =.702, ηp2 = 0.00) or main effects of time (F(1, 78) = 2.105; p =.151, ηp2 = 0.03) or intervention (F(1, 78) = 0.366; p =.547, ηp2 = 0.01). Means and standard deviations for RMSSD and HR scores are shown in Supplementary Materials Table S5.

Temporal dynamics analyses confirmed these findings. HR was significantly higher under the control condition during seconds 20–30 (Cohen’s d: 0.20 ± 0.10; small effect size) compared to RB; see Fig. 4A. RMSSD scores were significantly higher under RB beginning at second 30 (Cohen’s d: 0.57 ± 0.18; moderate-to-large effect size); see Fig. 4B.

User experience after mCPT

No significant differences were observed between the two stress recovery interventions for perceived usefulness (RB: 5.1 ± 1.1; control: 5.3 ± 1.1; p =.316, d = 0.23) or ease of use (RB: 4.6 ± 1.4; control: 4.2 ± 1.5; p =.220, d = 0.27). However, RB was perceived as significantly more enjoyable (RB: 4.3 ± 1.4; control: 3.3 ± 1.9; p =.012, d = 0.57).

Stress induction 2 (PASAT-C)

Effectiveness of PASAT-C

The PASAT-C significantly increased subjective stress (stress scale) with a large effect size (pre: 0.8 ± 0.8; post: 2.7 ± 1.1), (t(79) = 14.197, p <.001, d = 1.59. HR remained relatively stable (79.9 ± 14.2 beats per minute) with a brief elevation when difficulty level 3 started at 480 s (84.2 ± 14.3 beats per minute); see Fig. 5A. RMSSD was elevated during difficulty level 1 (38.9 ± 25.6 ms), decreased steadily during level 2 to 33.3 ± 19.6 ms, and reached minimum levels after 7 min of level 3 (30.1 ± 16.9 ms) before showing slight recovery; see Fig. 5B.

Stress recovery after PASAT-C

A mixed ANOVA showed no significant time x intervention interaction for subjective stress (F(1,78) = 0.048, p =.827, ηp2 = 0.00) or main effect of intervention (F(1,78) = 2.989, p =.09, ηp2 = 0.04). The factor time demonstrated a significant main effect with a large effect size, showing decreased stress under both stress recovery interventions (F(1,78) = 130.596, p <.001, ηp2 = 0.63). In contrast, perceived strain (KAB) was significantly higher (with a moderate effect size) after standard rest (control) compared to RB (RB: 4.0 ± 0.9; control: 4.6 ± 0.6; t(78) = 3.698, p <.001, d = 0.83). Means and standard deviations for both scales are shown in Supplementary Materials Table S4.

For RMSSD, a significant interaction effect with a large effect size was observed (F(1,78) = 13.621, p <.001, ηp2 = 0.15). Post-hoc tests revealed significant RMSSD increases for both RB (p <.001) and control (p <.001), and a significant difference in RMSSD scores between the two stress recovery interventions (p =.040); see Fig. 6. HR showed no significant interaction (F (1, 78) = 0.258; p =.613, ηp2 = 0.00) or main effect of intervention (F (1, 78) = 0.361; p =.550, ηp2 = 0.01), but the main factor time reached significance with a moderate effect size (F (1, 78) = 10.180; p =.002, ηp2 = 0.12), indicating lower HR during recovery compared to during the PASAT-C. Means and standard deviations for RMSSD and HR scores are shown in Supplementary Materials Table S5.

Temporal analyses revealed minimal HR differences except for brief periods (seconds 5–8 and 223–225, Cohen’s d: 0.17 ± 0.13; see Fig. 7A). RMSSD scores were significantly higher under RB during the first half of the recovery period for 93 s (between seconds 42–143; Cohen’s d: 0.21 ± 0.18), see Fig. 7B.

User experiences after PASAT-C

RB demonstrated significantly higher perceived usefulness (greater efficiency, with a moderate effect size) compared to the control condition (RB: 4.3 ± 1.4; control :3.3 ± 1.9), t(78) = 2.565, p =.012, d = 0.57. In contrast, ease of use was significantly lower (with a moderate effect size) for RB (4.0 ± 1.7) compared to the control condition (5.0 ± 1.0); t(78) = 3.176, p =.002, d = 0.71. RB was perceived as significantly more enjoyable (more exiting) with a large effect size (RB: 4.4 ± 1.3; control: 2.4 ± 1.6); t(78) = 5.931, p <.001, d = 1.33.

Discussion

This controlled laboratory study investigated the psychophysiological stress recovery effects of light-guided RB following exposure to two distinct stress induction protocols. The findings demonstrate that RB significantly enhances parasympathetic recovery, as evidenced by increased HRV (RMSSD), following both modified physical (mCPT) and cognitive (PASAT-C) stress induction protocols. The study revealed differential stress recovery responses between stressor types, with RB showing particularly pronounced benefits following cognitive stress exposure. These results provide novel insights into stressor-intervention specificity and potential applications in occupational settings.

Distinct Psychophysiological stress responses to different stressors

The two stress induction protocols generated markedly different psychophysiological response patterns, emphasizing the importance of stressor specificity in stress recovery research42.

Unlike traditional cold pressor paradigms25,43, the mCPT showed initial sympathetic activation (increased HR) followed by parasympathetic compensation with decreasing HR and increasing RMSSD. This cardiac autonomic response extends results from a recent meta-analysis showing enhanced PNS activity during cold water immersion44. Notably, the mCPT did not significantly alter subjective stress levels. This absence of perceived stress increase, despite a distinct cardiovascular response, reveals a dissociation between physiological reactions and subjective appraisals of study participants. This finding suggests that the competitive context may have reframed the stressor from a threat into a manageable challenge (95% succeeded), aligning with biopsychosocial challenge-threat models45. Additionally, Psychology students, who comprised 71% of the sample and actively train stress management skills, may have further contributed to unexpectedly low subjective stress ratings.

In contrast, the PASAT-C induced robust subjective and cardiovascular stress responses26. Temporal dynamics revealed higher initial parasympathetic activity during difficulty level 1, followed by systematic PNS decline as cognitive demands intensified. This pattern aligns with cognitive load theories and executive resource depletion models46, demonstrating protocol effectiveness for simulating sustained workplace cognitive stress.

Differential stress recovery responses

RB effects differed markedly between stress induction procedures, revealing important insights into intervention specificity.

RMSSD changes after both stress protocols provide evidence for RB efficacy in enhancing autonomic recovery, supporting previous research demonstrating that slow breathing promotes parasympathetic activation10,11. However, temporal dynamics differed notably different between stressors: RB generated sustained parasympathetic activation during 5-minute recovery after mCPT, but elicited fast, temporally limited activation after PASAT-C. These patterns suggest that RB effects after mCPT may build upon existing PNS activation, whereas RB after PASAT-C initially compensated for comprehensive psychophysiological stress in a more transient manner. The exact mechanisms underlying this temporally limited response following cognitive stress warrant further investigation.

HR showed distinct recovery patterns that varied by preceding stressor. After mCPT, which had already decreased HR during the stressor itself, HR did not further decrease during recovery under either intervention. After PASAT-C, which had no significant HR effect but generated a marked decrease in RMSSD and increase in subjective stress, both interventions produced significant HR reductions during recovery. Since HR reflects both sympathetic and parasympathetic input, these findings suggest that HR may serve as a more sensitive stress recovery marker after comprehensive stress responses, such as those observed with PASAT-C in this study27.

Subjective stress, measured with a 1-item pictorial Likert scale, decreased with large effect sizes to similar extents during both recovery interventions after both stress protocols, indicating that a 5-minute break provides substantial subjective stress relief regardless of specific recovery activity.

Notably, RB resulted in significantly lower psychological and physiological strain compared to passive rest only after cognitive stress recovery. Since cognitive stressors provoke both cognitive and emotional responses, RB may reduce subjective strain by regulating both emotional and physiological arousal47. This finding aligns with the dual-process model of stress recovery48, which suggests that effective interventions must address both cognitive-emotional and physiological components of the stress response.

User experiences of stress recovery interventions

RB was consistently perceived as more enjoyable after both stressors, with particularly strong preferences emerging after cognitive stress. Enjoyment is critical for long-term adherence to stress management practices49, suggesting that the light-guided breathing intervention may have substantial potential for sustained use in real-world settings.

User experience profiles also differed between stressors. Following mCPT, RB showed no differences in perceived usefulness or ease of use compared to passive rest. This suggests that while participants found the breathing intervention pleasant, they may not have perceived clear functional benefits for stress recovery after mCPT. This finding is substantiated by similar levels of perceived strain after both recovery interventions.

Following cognitive stress, RB demonstrated higher perceived usefulness but lower ease of use compared to passive rest. This finding indicates that participants recognized RB effectiveness for cognitive stress recovery but also acknowledged the cognitive effort required to engage with the intervention. From a practical perspective, this finding suggests that RB may be most valuable for cognitively demanding work situations where employees are motivated to invest effort in active recovery strategies.

Theoretical implications

These findings contribute to several theoretical frameworks in stress and recovery research. First, they support the concept of stressor-recovery specificity, suggesting that optimal recovery interventions should match the nature of the preceding stressor50. The differential effectiveness of RB aligns with the conservation of resources theory51, which posits that recovery activities should replenish specific resources depleted by stress exposure. Second, our results extend the understanding of RB mechanisms. The sustained parasympathetic activation following mCPT versus the transient response following cognitive stress suggests that RB may operate through different pathways depending on the autonomic starting point. This observation supports the allostatic load model52, which emphasizes flexible physiological responses to changing demands. Third, integrating visual guidance through workplace-compatible lighting represents a novel approach to breathing interventions. High enjoyment ratings suggest that environmental design elements can enhance the acceptability of stress management techniques, supporting ecological approaches to workplace wellbeing53.

Study limitations

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, although the intervention demonstrated the effectiveness of a single RB session in a controlled laboratory setting, further research is needed to examine its effectiveness in real-world workplace environments. Second, the stress induction methods did not address emotional stress, which plays a critical role in occupational stress21. Third, the 1-item pictorial stress scale may have lacked sensitivity to detect intervention-specific changes in subjective stress. Future studies should include multidimensional stress measures. Fourth, emerging evidence suggests that specific breathing techniques may have differential effects on stress modulation54. However, no explicit breathing instructions were given in this study, nor were breathing rates objectively monitored. Fifth, RB was conducted at the workstation in a seated position. However, promoting stress recovery while remaining seated may reinforce sedentary behavior, which is a known risk factor of reduced health55,56. Future studies could explore the combined effects of light physical activity with breathing exercises. Sixth, the study applied RB without real-time physiological feedback. HRV biofeedback training has shown strong effects on stress13 and in simulated work settings17,57. Future studies should investigate the non-inferiority of RB compared to HRV biofeedback. Seventh, the sample consisted of healthy young university students, which limits the generalizability of the findings to broader populations, including older workers or those with pre-existing health conditions. Finally, this study did not control for individual differences in daily-life stress recovery methods, which may have influenced results.

Conclusions

This study provides robust evidence that light-guided RB represents an effective intervention for workplace stress recovery. The differential benefits across stressor types highlight the importance of considering stressor-intervention specificity in the design and implementation of workplace stress management programs. The rapid autonomic recovery effects, combined with positive user experiences, support the potential of RB as occupational health intervention. These findings contribute to the growing evidence for brief, targeted stress recovery strategies that can be seamlessly integrated into modern work environments. The development of personalized, context-aware stress recovery interventions that adapt to individual needs and workplace demands represents a promising direction for occupational health research.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CPT:

-

Cold Pressor Test

- HR:

-

Heart Rate

- HRV:

-

Heart Rate Variability

- IBI:

-

Interbeat Interval

- PASAT-C:

-

Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task

- PNS:

-

Parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system

- ηp2 :

-

Partial eta-squared effect size

- RMSSD:

-

Root Mean Squared Successive Differences of IBI data

- SNS:

-

Sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system

References

Lazarus, R.S., & Folkman, S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company, ISBN 9780826141910 (1984).

American Psychological Association. Work and Well-being Survey. (2021). Available from: https://www.apa.org/pubs/reports/work-well-being

World Health Organization. Mental health in the workplace. (2019). Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/in_the_workplace/en/

Xu, G., Zheng, Z., Zhang, J., Sun, T. & Liu, G. Does digitalization benefit employees? A systematic Meta-Analysis of the digital Technology–Employee nexus in the workplace. Systems 13 (6), 409. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060409 (2025).

Richardson, K. M. & Rothstein, H. R. Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: A meta-analysis. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 13 (1), 69–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.13.1.69 (2008).

Joyce, S. et al. Workplace interventions for common mental disorders: A systematic meta-review. Psychol. Med. 46 (4), 683–697. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002408 (2016).

Tamminga, S. et al. Individual-level interventions for reducing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5 (5), CD002892. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002892.pub6 (2023).

Denuwara, B., Gunawardena, N., Dayabandara, M. & Samaranayake, D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of individual-level interventions to reduce occupational stress perceptions among teachers. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health. 77 (7), 530–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/19338244.2021.1958738 (2022).

Shao, R., Man, I. S. C. & Lee, T. M. C. The effect of slow-paced breathing on cardiovascular and emotion functions: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Mindfulness 15 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02294-2 (2024).

Lehrer, P. M. & Gevirtz, R. Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work? Front. Psychol. 5, 756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756 (2014).

Sevoz-Couche, C. & Laborde, S. Heart rate variability and slow-paced breathing: when coherence Meets resonance. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 135, 104576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104576 (2022).

Lin, I. M., Tai, L. Y. & Fan, S. Y. Breathing at a rate of 5.5 breaths per minute with equal inhalation-to-exhalation ratio increases heart rate variability. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 91 (3), 206–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.12.006 (2013).

Goessl, V. C., Curtiss, J. E. & Hofmann, S. G. The effect of heart rate variability biofeedback training on stress and anxiety: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 47, 2578–2586. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717001003 (2017).

Laborde, S. et al. Effects of voluntary slow breathing on heart rate and heart rate variability: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 138, 104711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104711 (2022).

Fincham, G. W., Strauss, C., Montero-Marin, J. & Cavanagh, K. Effect of breathwork on stress and mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised-controlled trials. Sci. Rep. 13, 432. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27247-y (2023).

Steffen, P. R., Austin, T., DeBarros, A. & Brown, T. The impact of resonance frequency breathing on measures of heart rate Variability, blood Pressure, and mood. Front. Public. Health. 5, 222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00222 (2017).

Schlatter, S. T. et al. Effects of relaxing breathing paired with cardiac biofeedback on performance and relaxation during critical simulated situations: a prospective randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. Educ. 22 (1), 422. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03420-9 (2022).

Liang, W. M. et al. Acute effect of breathing exercises on muscle tension and executive function under psychological stress. Front. Psychol. 14, 1155134. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1155134 (2023).

Masmoudi, K., Chaari, F., Ben Waer, F., Rebai, H. & Sahli, S. A single session of slow-paced breathing improved cognitive functions and postural control among middle-aged women: a randomized single blinded controlled trial. Menopause 32 (2), 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000002470 (2025).

Blum, J., Rockstroh, C. & Göritz, A. S. Heart rate variability biofeedback based on slow-paced breathing with immersive virtual reality nature scenery. Front. Psychol. 10, 2172. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02172 (2019).

Chelidoni, O., Plans, D., Ponzo, S., Morelli, D. & Cropley, M. Exploring the effects of a brief biofeedback breathing session delivered through the biobase app in facilitating employee stress recovery: randomized experimental study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 8 (10), e19412. https://doi.org/10.2196/19412 (2020).

Lasauskaite, R., Wüst, L. N., Schöllborn, I. & Richter, M. Cajochen C. Non-image forming effects of daytime electric light exposure in humans: a systematic review and meta-analyses of physiological, cognitive, and subjective outcomes. Leukos 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/15502724.2025.2493669 (2025).

Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E. & Vaschillo, B. Resonant frequency biofeedback training to increase cardiac variability: rationale and manual for training. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback. 25 (3), 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009554825745 (2000).

The WHOQOL Group. Development of the world health organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol. Med. 28 (3), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291798006667 (1998).

Schwabe, L. & Schächinger, H. Ten years of research with the socially evaluated cold pressor test: data from the past and guidelines for the future. Psychoneuroendocrinology 92, 155–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.03.010 (2018).

Lejuez, C. W., Aklin, W. M., Zvolensky, M. J. & Pedulla, C. M. Evaluation of the balloon analogue risk task (BART) as a predictor of adolescent real-world risk-taking behaviours. J. Adolesc. 26 (4), 475–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-1971(03)00036-8 (2003).

Hjortskov, N. et al. The effect of mental stress on heart rate variability and blood pressure during computer work. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 92(1–2), 84–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-004-1055-z (2004).

Wehrwein, E. A., Orer, H. S. & Barman, S. M. Overview of the anatomy, physiology, and Pharmacology of the autonomic nervous system. Compr. Physiol. 6 (3), 1239–1278. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c150037 (2016).

Thomas, B. L., Claassen, N., Becker, P. & Viljoen, M. Validity of commonly used heart rate variability markers of autonomic nervous system function. Neuropsychobiology 78 (1), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1159/000495519 (2019).

Minarini, G. Root Mean Square of the Successive Differences as Marker of the Parasympathetic System and Difference in the Outcome after ANS Stimulation. In: Aslanidis T, editor. Autonomic Nervous System Monitoring—Heart Rate Variability. London: IntechOpen (2020). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.89827

Pereira, T., Almeida, P. R., Cunha, J. P. & Aguiar, A. Heart rate variability metrics for fine-grained stress level assessment. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 148, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2017.06.018 (2017).

Gilgen-Ammann, R., Schweizer, T. & Wyss, T. RR interval signal quality of a heart rate monitor and an ECG Holter at rest and during exercise. Europ J Appl Physio. 119, 1525–1532 (2019).

Rincon Soler, A. I., Silva, L. E. V., Fazan, R. & Murta, L. O. The impact of artifact correction methods of RR series on heart rate variability parameters. J Appl Physio. 124(3), 646–652 (2018).

Nussinovitch, U. et al. Reliability of ultra-short ECG indices for heart rate variability. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 16, 117–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-474X.2011.00417.x (2011).

Buchberger, W. et al. Selbsteinschätzung von psychischem Stress mittels Single-Item Skala. Pflegewissenschaft 22, 24–29. https://doi.org/10.3936/1691 (2019).

Elo, A. L., Leppänen, A. & Jahkola, A. Validity of a single-item measure of stress symptoms. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 29 (6), 444–451. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.752 (2003).

Hicks, C. L., von Baeyer, C. L., Spafford, P. A., van Korlaar, I. & Goodenough, B. The faces pain Scale-Revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain 93 (2), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00314-1 (2001).

Müller, B., & Basler, H.D. Kurzfragebogen zur aktuellen Beanspruchung: KAB. Weinheim: Beltz (1993).

Schrepp, M., Hinderks, A. & Thomaschewski, J. Design and evaluation of a short version of the user experience questionnaire (UEQ-S). Int. J. Interact. Multimed Artif. Intell. 4 (6), 103. https://doi.org/10.9781/ijimai.2017.09.001 (2017).

Shaffer, F. & Meehan, Z. M. A practical guide to resonance frequency assessment for heart rate variability biofeedback. Front. Neurosci. 14, 570400. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.570400 (2020).

Brown, T. M. et al. Recommendations for daytime, evening, and nighttime light exposure to best support physiology, sleep, and wakefulness in healthy adults. PLOS Biology 20(3), e3001571. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001571 (2022).

Dickerson, S. S. & Kemeny, M. E. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull. 130(3), 355–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355 (2004).

Lovallo, W. The cold pressor test and autonomic function: a review and integration. Psychophysiology 12 (3), 268–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1975.tb01289.x (1975).

Jdidi, H., Dugué, B., de Bisschop, C., Dupuy, O. & Douzi, W. The effects of cold exposure (cold water immersion, whole- and partial- body cryostimulation) on cardiovascular and cardiac autonomic control responses in healthy individuals: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. J. Therm. Biol. 121, 103857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2024.103857 (2024).

Blascovich, J. & Mendes, W. B. Challenge and threat appraisals: the role of affective cues. In (ed Forgas, J. P.) Feeling and Thinking: the Role of Affect in Social Cognition (59–82). Cambridge University Press (2000).

Kahneman, D. & Prentice-Hall Attention and effort. ISBN 0-13-050518-8 (1973).

Thayer, J. F., Åhs, F., Fredrikson, M., Sollers, J. J. & Wager, T. D. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 36 (2), 747–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.009 (2012).

Taris, T. W. & Schaufeli, W. B. The job demands-resources model: A dual-process model of employee well-being? In (eds Burke, R. J. & Cooper, C. L.) The Handbook of Stress and Health: A Guide To Research and Practice (57–74). Edward Elgar Publishing (2015).

Vitoulas, S. et al. The effect of physiotherapy interventions in the workplace through active micro-break activities for employees with standing and sedentary work. Healthcare. 10(10), 2073. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10102073 (2022).

Sonnentag, S. & Fritz, C. Recovery from job stress: the stressor-detachment model as an integrative framework. J. Organiz Behav. 36 (S1), 72–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1924 (2015).

Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44 (3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513 (1989).

McEwen, B. S. Stress, adaptation, and disease: allostasis and allostatic load. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 840 (1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x (1998).

Thatcher, A. & Yeow, P. H. P. A sustainable system of systems approach: A new HFE paradigm. Ergonomics 59 (2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2015.1066876 (2016).

Laborde, S. et al. Slow-paced breathing: influence of inhalation/exhalation ratio and of respiratory pauses on cardiac vagal activity. Sustainability 13 (14), 7775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147775 (2021).

Biswas, A. et al. Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 162 (2), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-1651 (2015).

Onagbiye, S. O., Guddemi, P. R., Alberti, F., Baattjes, H. & Tsolekile, L. Association between sedentary behaviour and mental health among university students in Western Cape, South Africa, considering physical activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20 (4), 3113. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043113 (2023).

Bahameish, M. & Stockman, T. Short-Term effects of heart rate variability biofeedback on working memory. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback. 49 (2), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-024-09624-7 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C., V.D. and E.M.W.; methodology, M.C., L.G., S.S., V.D., J.W. and E.M.W.; formal analysis, M.C., L.G., S.S.; investigation, L.G. and S.S.; data curation, L.G. and S.S; Writing - original draft preparation, M.C., V.D. and E.M.W.; Writing - review & editing, M.C., L.G., S.S., V.D., J.W. and E.M.W.; project administration, M.C., L.G. and E.M.W.; funding acquisition, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the University of Innsbruck, Austria (No.93/2023). Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to participation. Data confidentiality was guaranteed and the subjects were informed that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Informed consent statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Canazei, M., Glenzer, L., Staggl, S. et al. Light-guided resonant breathing enhances psychophysiological stress recovery in a simulated office environment. Sci Rep 15, 40953 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24813-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24813-y