Abstract

Postdoctoral researchers play a critical role in advancing global science, yet widespread job dissatisfaction threatens both their retention and research productivity. Although prior studies have identified discrete factors affecting postdoctoral job satisfaction, the complex, configurational relationships among them remain poorly understood. To bridge this gap, our study draws on Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory and employs fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) to explore how different configurations of key motivational factors jointly shape postdoctoral job satisfaction. Analyzing data from the 2023 Nature Global Postdoctoral Survey, we identified eight distinct configurational pathways—five associated with high satisfaction and three with low. These findings provide actionable evidence for institutions to tailor support strategies that better serve postdoctoral needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postdoctoral researchers (PDRs), commonly referred to as “postdocs,” are individuals with extensive education, specialized skills, and significant productivity1. They have played a pivotal role in advancing research, innovation, arts, culture, science, and policymaking worldwide2,3,4. At the individual level, research has shown that engaging in postdoctoral positions could not only enhance the quantity of scientific contributions later in one’s academic journey but also facilitate a stronger integration into global academic networks5,6. In this context, the number of PDRs has grown substantially across various countries. Indeed, according to the National Science Foundation, the number of PDRs in science and engineering at U.S. universities rose by 4.9% in a single year, from 62,750 in 2022 to 65,850 in 2023 (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Survey of Graduate Students and Postdoctorates in Science and Engineering).

Nevertheless, this rapid growth has coincided with a deepening career crisis within the postdoctoral workforce. According to the first global follow-up survey conducted by Nature in 2020, involving 7,670 PDRs across 93 countries, nearly 40% of participants planned to leave the scientific research community after one year of work7. The study highlighted that the global postdoctoral community is facing one of the most severe career crises in recent history, with declining job satisfaction identified as the primary driver of this trend. A more recent survey conducted by the US National Postdoctoral Association8 further confirmed that widespread dissatisfaction persists among US PDRs. Such an environment of low job satisfaction not only reduces scientific research output but also leads many PDRs to reconsider their career paths9, exacerbating high attrition rates10,11. In the long run, this trend will inevitably impede national academic advancement and undermine the efficiency of scientific and technological innovation.

It is therefore essential to investigate the mechanisms that enhance postdoctoral job satisfaction to ensure the sustainable development of academia and support countries’ sci-tech advancement. Existing research has identified multiple factors associated with postdoctoral job satisfaction, including the work itself, relationships with management and colleagues12, income, independence in work13, peer support14, work-life balance15, institutional recognition16, and etc. While these findings have greatly advanced our understanding of the correlates of postdoctoral job satisfaction, most studies examined these factors in isolation or as net effects. Therefore, it is quite unclear which combinations of the previously identified factors better explain the obtained assessment outcome.

To address this gap, this study draws on Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory (1959) as a guiding framework to systematically identify the relevant factors and adopts a configurational approach using fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA17) to explore how these factors combine to shape postdoctoral job satisfaction. In doing so, we aim to contribute to better explaining postdoctoral job satisfaction and offer empirical evidence to inform strategies for improving the postdoctoral experience and enhancing job fulfillment.

Literature review and theoretical framework

Postdoctoral job satisfaction and its impact

There is currently no universal agreement among researchers on the definition of job satisfaction. One widely cited definition describes job satisfaction as “the degree to which people like their jobs” (18, p. 7). Scholars often conceptualize job satisfaction as a multidimensional construct, reflecting employees’ feelings toward various aspects of their work, including the work itself, payment, opportunities for promotion, and relationships with colleagues19. In recent years, this foundational concept from organizational behavior has been increasingly applied in educational research to examine postdoctoral job satisfaction. At its core, postdoctoral job satisfaction reflects how PDRs emotionally and cognitively evaluate their work experiences and professional roles20.

Research on postdoctoral job satisfaction has been conducted over the years. As early as 1999, Science reported that PDRs were dissatisfied with work pressure and employment conditions21. More recent global postdoctoral surveys published by Nature found that approximately 60% of respondents were satisfied with their jobs in 2020, but this figure declined to 55% in 2023, indicating a downward trend in overall satisfaction22. Similarly, Nature’s 2021 Global Compensation and Satisfaction Survey revealed an average job satisfaction score of 2.43 out of 5—below the neutral midpoint—highlighting a general sense of dissatisfaction among PDRs23. This growing dissatisfaction inevitably leads to negative consequences at the individual, institutional, and societal levels. Empirical studies have shown that PDRs with lower job satisfaction are more likely to experience mental health problems, particularly when dissatisfaction arises from poor work-family balance or unclear academic career prospects10,24. Professionally, low job satisfaction among PDRs has been associated with reduced research productivity25 and, in more severe cases, a heightened intention to leave academia (e.g.26,27,28). This trend appears to be more pronounced among female PDRs, who tend to be more vulnerable to the negative impacts of dissatisfaction11. At the societal level, these effects not only reduce future research outcomes at universities25 but also result in a loss of personal investment and public resources allocated to postdoctoral training29. Therefore, greater attention must be paid to improving postdoctoral job satisfaction.

Antecedents of postdoctoral job satisfaction

Postdoctoral job satisfaction is shaped by a range of complex and interrelated factors. Building on Herzberg’s two-factor theory, Hagedorn30 categorized academic faculty job satisfaction into three broad domains: demographics, representing personal attributes, motivators and hygienes, referring to individual work experience; and environmental conditions, encompassing organizational and broader contextual influences.

Regarding demographic characteristics, studies have shown that factors such as gender, nationality, academic discipline, and the length of employment significantly influence postdoctoral job satisfaction. Female PDRs often report lower satisfaction due to more adverse working conditions and gender bias11,31, while international PDRs tend to be less satisfied than their local counterparts32. Satisfaction also varies by academic disciplines, with PDRs in humanities and social sciences reporting lower levels than those in the hard sciences32. Additionally, extended periods in postdoctoral positions are associated with declining satisfaction, often reflecting concerns over job insecurity and limited career prospects33,34.

When it comes to individual work-related factors, postdoctoral job satisfaction is influenced by both tangible factors, such as salary35, and less tangible factors, such as opportunities for advancement and professional growth. Specifically, advancement opportunities are critical, as uncertainty about long-term academic prospects can lower PDRs’ job satisfaction32, while growth through skill development contributes positively to their satisfaction36. A sense of responsibility, reflected in job autonomy, is another key driver, as PDRs who have control over their time and research focus reported higher levels of satisfaction24,37. Similarly, PDRs who engage in work aligned with their personal interests are more likely to experience higher job satisfaction20. A sense of achievement, derived from successfully meeting professional goals, can also enhance satisfaction38. Finally, external recognition, particularly through journal publications, reinforces academic success and professional identity, thereby contributing to postdoctoral job satisfaction25.

At the organizational and environmental level, postdoctoral job satisfaction is significantly influenced by institutional support, collegial relationships, and overall workplace climate. For instance, Scaffidi and Berman39 found that PDRs report more positive experiences when they receive quality supervision, have opportunities for collaboration and networking, and work within a nurturing research environment. In addition, a positive collegial climate, characterized by supportive relationships with peers and colleagues, is powerfully associated with greater job satisfaction40. Similarly, a generally positive working atmosphere has been identified as a key contributor to postdoctoral job satisfaction41,42.

While the aforementioned research has identified various factors influencing postdoctoral job satisfaction, such relationships are often presented as symmetrical, linear, and unidirectional, with influencing factors treated as independent of one another. However, postdoctoral job satisfaction is likely shaped by complex combinations of multiple factors, which traditional variance-based methods may fail to fully capture43. To address this, we employed fsQCA, a method designed to analyze complex combinations and interdependencies between various factors. By revealing asymmetric relationships, where the presence and absence of certain conditions lead to different outcomes, our study goes beyond prior studies, offering a novel explanation of postdoctoral job satisfaction.

Theoretical foundation and conceptual model

The Two-Factor Theory, developed by Herzberg and his colleagues44,45, serves as a foundational framework for understanding job satisfaction. Recent studies have extended its application to academic settings, using it to define and categorize the factors that influence job satisfaction among PDRs46. According to the theory, job satisfaction is shaped by two distinct sets of factors: motivators and hygiene factors. Herzberg emphasized that these two sets of factors are not opposites on a single continuum but operate independently. Motivators relate to the content of the work and reflect employees’ psychological needs—such as achievement, recognition, responsibility, meaningful work, opportunities for growth and advancement. Their presence increases satisfaction. In contrast, hygiene factors are tied to the work environment and reflect basic expectations—such as salary, job security, working conditions, company policies, interpersonal relations, and status. While their presence decreases dissatisfaction, they do not directly contribute to satisfaction44,47.

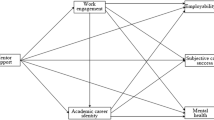

Given that the aim of this study is to identify the factors that contribute to postdoctoral job satisfaction, we adopt Herzberg’s classification and focus on the six core motivational dimensions: achievement, recognition, the work itself, responsibility, advancement, and growth. While other theories, such as Self-Determination Theory48 and the Job Characteristics Model49, also address intrinsic motivation, they focus more on the psychological mechanisms behind motivation. In contrast, Herzberg’s framework provides a clear categorization of motivational factors that directly contribute to job satisfaction, making it more suitable for this study’s focus. Building on this framework, we employed fsQCA to examine how different configurations of these key motivational factors jointly shape postdoctoral job satisfaction. It is important to note that the exploratory nature of fsQCA means this study seeks to identify different configurations of conditions rather than test linear hypotheses. Therefore, we do not propose traditional hypotheses but instead propose the core research question: What configurations of motivators are associated with postdoctoral job satisfaction? To guide this analysis, we present the following conceptual model (see Fig. 1).

Method

Ethics declarations

This study is based on the secondary analysis of publicly available data from the 2023 Nature Global Postdoctoral Survey, which was accessed from the Figshare repository on 7 May 2025. The dataset comprises fully anonymized and aggregated survey responses, and the authors had no access to any personally identifiable information at any stage of the analysis. All analyses were conducted in accordance with relevant ethical guidelines and regulations.

Sample

The data used in this study is derived from the Nature 2023 Postdocs Survey, which encompasses a wide range of information, including respondent profiles, salary and benefits, job satisfaction, and postdoctoral experiences, among other aspects. The global valid sample size comprises 3,838 respondents. Of these, 1,712 are European PDRs, representing 45% of the total sample. The remaining respondents are distributed across other regions, including North and Central America (38%), Asia (10%), Australasia (3%), Africa (2%), and South America (2%). In terms of disciplinary distribution, the majority of respondents are engaged in biomedical and clinical sciences (53%), followed by ecology and evolution (6%), chemistry (6%), healthcare (6%), agriculture and food (5%), engineering (5%), geology and environmental science (5%), physics (5%), and social sciences (5%). Regarding gender distribution, females constitute 51% of the sample, while males account for 47%. With regard to employment, 61% were working abroad, 48% had been PDRs for two years or less, and 4% were employed outside universities or research institutions. Overall, the survey sample is both extensive and representative, providing a robust foundation for analysis.

Variables

The survey instrument used a 7-point Likert scale, with response options ranging from 1 (“extremely dissatisfied”) to 7 (“extremely satisfied”). The dependent variable, postdoctoral job satisfaction, was measured by the item: “How satisfied are you with your current postdoctoral work?” Guided by the Two-Factor Theory44, which posited that the fulfillment of motivational factors can significantly enhance job satisfaction, this study selected independent variables from survey items reflecting such factors. These include advancement, the work itself, possibility of growth, responsibility, recognition, and achievement. Career advancement was assessed through the item “Career advancement opportunities.” Work itself was measured by “My interest in the work,” reflecting alignment between research tasks and intellectual motivation. Growth encompassed two dimensions: project-based development (“Opportunity to work on interesting projects”) and formal skill acquisition (“Access to workplace-sponsored training and seminars”). Responsibility indicators included autonomy (“My degree of independence”) and agency (“Ability to influence decisions that affect you”). Recognition focused on performance acknowledgment through “Recognition for achievements,” while achievement captured intrinsic motivation via “Personal sense of accomplishment.”

Data analysis

This study adopted fsQCA, a method well-suited for examining complex configurations of constructs50. Unlike traditional correlation-based quantitative methods, fsQCA focuses on how different combinations of antecedent conditions jointly influence an outcome, thereby emphasizing the synergistic effects among multiple influencing factors. A key feature of fsQCA is its ability to distinguish between core and peripheral conditions, where core conditions indicate a strong causal relationship with the outcome, while peripheral conditions exhibit a weaker causal link51. This configurational approach enables fsQCA to overcome certain limitations inherent in linear methods such as multiple regression analysis, particularly in capturing causal asymmetry. Given the multifaceted nature of factors influencing postdoctoral job satisfaction, as evidenced by prior literature, fsQCA was chosen in this study to identify specific combinations of necessary and sufficient conditions that contribute to PDRs’ overall job satisfaction.

Pre-processing

The fsQCA requires the calibration of raw data into a range of values between 0 and 1, where 1 signifies complete affiliation, 0 indicates complete disaffiliation, and values between 0 and 1 represent varying degrees of membership. This process involves defining three critical anchors for each variable: the full membership threshold, the full non-membership threshold, and the crossover point17. These anchors help determine whether a variable is included or excluded from a specific set52. In this study, the direct method17 was employed to address this calibration requirement. Researcher-specified qualitative anchors were used to identify the 5th percentile (minimum threshold), 95th percentile (maximum threshold), and 50th percentile (crossover point) values. Following the approach suggested by Ordanini et al.53, three anchor points were established on a Likert 7-point scale: 6 for complete affiliation, 4 for the crossover point, and 2 for complete disaffiliation. Based on these calibrated fuzzy sets, necessary and sufficient condition analyses were then conducted. The results of these analyses are presented and discussed in the following section.

Results and findings

Necessity analysis

Prior to conducting the fsQCA configuration analysis, this study first examined whether each antecedent condition qualified as a necessary condition for the occurrence of the desired outcome. Consistency serves as an important indicator for assessing necessary conditions, where a value exceeding 0.9 signifies that the antecedent condition can be a necessary condition for the outcome variable17. Coverage, on the other hand, measures the extent to which the solution accounts for all causal relationships, with values ranging from 0 to 1. Higher coverage values indicate a more robust empirical explanation of the observed results54.

As presented in Table 1, only The work itself (TWI) demonstrates consistency and coverage values of 0.934 (> 0.9) and 0.730 (> 0.5), respectively, meeting the thresholds for a necessary condition. This indicates that TWI qualifies as a necessary condition for high postdoctoral job satisfaction. To further validate this finding, we conducted an XY plot analysis. A necessary influence of X (TWI) on Y (postdoctoral job satisfaction) is confirmed when the consistency of X ≥ Y exceeds that of X ≤ Y. The results show that the consistency of X ≥ Y (0.934) significantly surpasses that of X ≤ Y (0.730), solidifying TWI as an approximate necessary condition for high postdoctoral job satisfaction. In contrast, the consistency values for other antecedent conditions—Advancement (Adv), Growth (Gr), Responsibility (Resp), Achievement (Ach), and Recognition (Rec)—fall below the 0.9 threshold. This suggests that none of these conditions, whether at high or low levels, constitute necessary conditions for high postdoctoral job satisfaction. Similarly, no single variable was identified as a necessary condition for low job satisfaction, indicating that no necessary conditions exist to produce the outcome of low postdoctoral job satisfaction.

Configuration construction

The sufficiency analysis of conditional configurations seeks to determine how different combinations of antecedent conditions contribute to the occurrence of the outcome54. For this analysis, the consistency threshold cannot be lower than 0.9, the frequency threshold, which is sample-dependent, should be greater than 1 for large samples, and the PRI consistency threshold is recommended to be at least 0.7552. In this study, we set the consistency threshold at 0.9, the frequency threshold at 5, and the PRI consistency threshold at 0.75. Based on these parameters, the fsQCA analysis yields three types of solutions: complex, intermediate, and parsimonious. A condition is considered core if it is present in both the intermediate and parsimonious solutions, indicating a strong and stable causal relationship with the outcome. If a condition appears solely in the intermediate solution, it is deemed peripheral, playing a supplementary role. According to this, we identified five configurations linked to high job satisfaction and three configurations associated with low job satisfaction (see Table 2). All configurations exceeded the consistency threshold of 0.9, supporting that configurations H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5 are sufficient for high job satisfaction, while configurations L1, L2, and L3 are sufficient for low job satisfaction.

indicates the presence of core conditions,

indicates the presence of core conditions,  indicates the presence of peripheral conditions,

indicates the presence of peripheral conditions,  indicates the absence of core conditions,

indicates the absence of core conditions,  indicates the absence of peripheral conditions, and “Blank” indicates “do not care”.

indicates the absence of peripheral conditions, and “Blank” indicates “do not care”.In detail, the results reveal two distinct groups of configurations that drive high job satisfaction among PDRs. (1) configuration H1 (Adv ∗ Gr ∗ TWI ∗ ∼Rec), H2 (Adv ∗ Gr ∗ TWI ∗ Resp), H3 (Adv ∗ Gr ∗ TWI ∗ Ach), and H5 (Adv ∗ Gr ∗ Rec ∗ Ach ∗ Resp) consistently identify advancement as the central driver of high job satisfaction among PDRs. However, advancement alone is insufficient and should be supplemented by other motivational factors. In fact, H2, which accounts for the largest proportion of high job satisfaction cases (54.2%), indicates that the combination of growth, responsibility, and meaningful work (the work itself) forms a strong foundation for high job satisfaction when paired with career advancement. Similarly, H3 explains a slightly smaller yet substantial share of satisfied PDRs, with a raw coverage of 53.3%, underscoring the reinforcing effect of achievement and growth opportunities alongside interesting work. In addition, H5 accounts for 48.7% of high job satisfaction cases and demonstrates that a comprehensive integration of advancement, growth, recognition, achievement, and responsibility creates a robust and well-rounded motivational framework. In contrast, H1 explains a smaller proportion of high job satisfaction cases (19.2%). This suggests that while career advancement combined with growth and meaningful work can drive satisfaction even in the absence of recognition, this pathway is less observed among satisfied PDRs. The overall variations in raw coverage highlight that while career advancement is a critical driver, its combination with other motivational factors—particularly growth, responsibility, and meaningful work—produces a more consistent and widely observed pattern of high job satisfaction. (2) configuration H4 (∼Gr*Rec ∗ Resp ∗ TWI ∗ Ach) demonstrates that even in the absence of career growth opportunities, high job satisfaction can still be achieved through recognition and responsibility. This indicates a substitution effect, where recognition and responsibility compensate for the lack of career advancement, thereby driving satisfaction.

Furthermore, the analysis identifies two groups of configurations that contribute to low job satisfaction among PDRs. (1) configuration L1 (∼TWI ∗ ∼Rec ∗ ∼Adv*∼Ach) highlights that the absence of meaningful work (the work itself) and recognition are primary drivers of low job satisfaction. The lack of advancement and achievement as peripheral conditions exacerbates this effect, further diminishing postdoctoral job satisfaction levels. (2) configurations L2 (∼Gr ∗ ∼Ach ∗ ∼Adv ∗ ∼Rec ∗ ∼Resp) and L3 (∼Gr ∗ ∼Ach ∗ ∼Adv ∗ ∼TWI ∗ ∼Resp) reveal that the absence of personal accomplishment and professional growth significantly undermines job satisfaction. When combined with the lack of career development (advancement), meaningful work (the work itself), and responsibility, these deficiencies result in a significant loss of motivation, as evidenced in the low job satisfaction cases represented by L3.

Discussion

This study employed fsQCA to investigate how configurations of motivational factors, including advancement, growth, the work itself, responsibility, achievement, and recognition, contribute to postdoctoral job satisfaction. Although previous studies have identified these key determinants, they have generally failed to uncover the asymmetric relationships among them. Our fsQCA results demonstrate that postdoctoral job satisfaction stems not from single factors but from distinct, asymmetric combinations of various motivators. These findings provide institutions with clear, strategic directions for enhancing postdoctoral satisfaction. The key findings from the analysis are presented below.

Core drivers of high satisfaction

In the configurational paths for a high level of postdoctoral job satisfaction, advancement constantly emerged as a core condition in four of the five configurations (H1, H2, H3, H5). This suggests that access to career development and promotion opportunities plays a crucial role in shaping postdoctoral job satisfaction. This pattern is supported by empirical studies grounded in Self-Determination Theory, which show that when an individual’s need for competence is fulfilled, their overall job satisfaction is likely to increase55,56. In academic contexts, Bozeman and Gaughan40 also found that access to promotion and tenure opportunities significantly increases satisfaction among university faculty.

Besides advancement as a core condition, other factors such as growth, responsibility, and achievement were identified as peripheral conditions contributing to postdoctoral job satisfaction. This finding confirms that postdoctoral job satisfaction does not result from a single factor but rather from configurations of multiple motivators. While advancement is crucial, it is insufficient by itself to ensure high job satisfaction; its impact is maximized when combined with additional reinforcing factors. For instance, the most frequently observed configurational pathway detected for postdoctoral job satisfaction is H2 (Adv * Gr * TWI * Resp), which suggests that PDRs who not only have access to career development and growth opportunities, but also show strong interest in their work and possess autonomy and control over their tasks, are more likely to report high satisfaction. This result echoes the findings of Marshall57, who argued that the interplay between intrinsic motivators can create a positive feedback loop, where factors mutually reinforce one another, thereby strengthening job satisfaction among university research administrators.

Compensatory motivators when growth is limited

Also in the configurations for high job satisfaction, H4 (~ Gr * Rec * Resp * TWI * Ach) with the presence of recognition and responsibility as core conditions in the absence of growth opportunities, indicates that when growth opportunities are lacking, job autonomy and sense of achievement serve as core compensatory conditions for maintaining high levels of job satisfaction among PDRs. This finding further underscores the importance of autonomy and recognition as key drivers of job satisfaction. Prior research has similarly highlighted the significance of social recognition, academic freedom, and participative decision-making in shaping satisfaction within academic settings58,59.

Furthermore, achievement and the work itself serve as the peripheral conditions, suggesting that the nature of the work and professional accomplishments, when combined with the core conditions of recognition and responsibility, can help compensate for the lack of career development prospects, contributing to sustained satisfaction. This observation partially aligns with Chen’s46 findings, which highlight the importance of job attractiveness and job fulfillment, as well as the establishment of teacher grievance mechanisms and the reward system, in enhancing academic employees’ job satisfaction.

Critical deficits undermine job satisfaction

Regarding the results for low job satisfaction, configuration L1 (~ TWI * ~ Rec * ~ Adv * ~ Ach) suggests that PDRs experience a lower level of job satisfaction when they have little interest in their work, lack recognition, have limited growth opportunities, and feel a lack of achievement. In this configuration, both the work itself and recognition are identified as core conditions contributing to low postdoctoral job satisfaction. When PDRs engage in work that does not align with their interests or is not undertaken for skills development, they are more likely to experience lower job satisfaction60. Additionally, a lack of recognition for their achievements can lead PDRs to consider leaving academia, underscoring the importance of recognition in sustaining job satisfaction37.

In configuration L2 (~ Gr * ~ Ach * ~ Adv * ~ Rec * ~ Resp), the absence of growth and achievement as core conditions in the configuration is sufficient for low job satisfaction. Given the explicitly developmental nature of the postdoctoral position, PDRs typically have high growth need strength60. Without sufficient opportunities for professional growth, they are likely to feel stagnant in their careers, leading to low satisfaction with the postdoctoral experience. Furthermore, the absence of a sense of achievement, namely, the inability to obtain grants and publish high-impact research, is also a main source of low satisfaction for PDRs10. In configuration L3 (~ growth * ~ achievement * ~ advancement * ~ the work itself * ~ responsibility), growth and achievement again emerge as core conditions, while the absence of advancement, the work itself, and responsibility as peripheral conditions further exacerbate this situation. This suggests that, to effectively improve job satisfaction, institutions must not only meet PDRs’ core needs for growth and achievement, but also strengthen career advancement opportunities, ensure meaningful and engaging work, and promote autonomy and responsibility in their roles.

Conclusion and implications

Drawing on Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory, this study employed fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) to explore how postdoctoral job satisfaction is shaped by the alternative configurations of six motivational factors: achievement, recognition, the work itself, responsibility, advancement, and growth. The results identified five configurations associated with high postdoctoral job satisfaction and three configurations linked to low satisfaction. Career advancement emerges as a core driver of high satisfaction, with its impact amplified when combined with other motivators such as growth opportunities, meaningful work, and responsibility. Second, recognition and responsibility function as compensatory core motivators that can sustain high satisfaction levels even when growth opportunities are constrained. Third, a lack of meaningful work and recognition constitutes a central pathway toward low satisfaction. Finally, the simultaneous absence of necessary conditions, growth, and achievement, together with the absence of peripheral factors such as advancement, meaningful work, and responsibility, further contributes to low satisfaction among PDRs.

These findings yielded a number of clear implications for enhancing postdoctoral job satisfaction. First and foremost, institutions should prioritize the development of transparent and structured career advancement pathways for PDRs, including clear criteria for promotion, transition-to-faculty tracks, and access to mentoring or networking opportunities. For PDRs on a defined advancement trajectory, institutions are encouraged to establish integrated career development programs that explicitly link promotion prospects with opportunities for professional growth, intellectually engaging work, and autonomy, thereby amplifying motivational outcomes. In contexts where growth opportunities are limited, creating an empowering work environment by granting PDRs greater intellectual autonomy and by providing regular recognition can serve as an effective compensatory mechanism to sustain their satisfaction. To prevent motivational decline, institutions should also ensure that postdoctoral roles are intellectually engaging and aligned with researchers’ expertise, interests, and long-term goals. Recognition should extend beyond formal achievements like publications and grants to include ongoing efforts, such as collaboration, problem-solving, and mentoring junior colleagues. Finally, attention should be paid to the combined absence of core motivators (i.e., opportunities for growth and a sense of achievement) and supporting conditions (i.e., career advancement prospects, meaningful work, and autonomy). When several of these elements are lacking at once, it may indicate deeper organizational issues. Early identification of such patterns, followed by targeted interventions, is essential for maintaining engagement, motivation, and long-term satisfaction among PDRs.

Like many empirical studies, this research has its limitations. First, the data were based on self-reported questionnaires, which could potentially be influenced by social desirability bias, thereby affecting the accuracy of the findings. To enhance validity, future research could adopt a mixed-methods approach, such as combining self-reports with behavioral observations. Additionally, while this study identified key motivational drivers of postdoctoral job satisfaction based on the two-factor theory, the possibility of the interplay between other influencing factors and alternative configuration paths remains unexplored and needs to be analyzed in future research. Furthermore, future research could adopt longitudinal designs to examine the dynamic evolution of configurational pathways over time. In particular, applying time-series QCA to panel data would offer a promising approach for capturing how pathways to postdoctoral job satisfaction vary across different stages of the academic career.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed for this study can be found in the figshare repository: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Nature_Post-Doctoral_Survey_2023/24236875.

References

O’Grady, T. & Beam, P. S. Postdoctoral scholars: a forgotten library constituency?. Sci. Technol. Libr. 30(1), 76–79 (2011).

Enders, J. Border crossings: Research training, knowledge dissemination, and the transformation of academic work. High. Educ. 49, 119–133 (2005).

Edge, J., & Munro, D. Inside and outside the academy: Valuing and preparing PhDs for careers. Conference Board of Canada= Le conference board du Canada. (2015).

Igami, M., Nagaoka, S. & Walsh, J. P. Contribution of postdoctoral fellows to fast-moving and competitive scientific research. J. Technol. Transf. 40, 723–741 (2015).

Lin, E. S. & Chiu, S. Y. Does holding a postdoctoral position bring benefits for advancing to academia?. Res. High. Educ. 57, 335–362 (2016).

Horta, H. Holding a post-doctoral position before becoming a faculty member: does it bring benefits for the scholarly enterprise?. High. Educ. 58(5), 689–721 (2009).

Woolston, C. Postdoc survey reveals disenchantment with working life. Nature 587(7834), 505–509 (2020).

National Postdoctoral Association. Postdoctoral barriers to success. (2023).

Stephan, P. & Ma, J. The increased frequency and duration of the postdoctorate career stage. Am. Econ. Rev. 95(2), 71–75 (2005).

Van der Weijden, I. & Teelken, C. Precarious careers: postdoctoral researchers and wellbeing at work. Stud. High. Educ. 48(10), 1595–1607 (2023).

Dorenkamp, I. & Weiß, E. E. What makes them leave? A path model of postdocs’ intentions to leave academia. High. Educ. 75, 747–767 (2018).

Hauff, S., Richter, N. F. & Tressin, T. Situational job characteristics and job satisfaction: The moderating role of national culture. Int. Bus. Rev. 24(4), 710–723 (2015).

Sousa-Poza, A. & Sousa-Poza, A. A. Well-being at work: a cross-national analysis of the levels and determinants of job satisfaction. J. Socio Econ. 29(6), 517–538 (2000).

Ducharme, L. J. & Martin, J. K. Unrewarding work, coworker support, and job satisfaction: A test of the buffering hypothesis. Work. Occup. 27(2), 223–243 (2000).

Irawanto, D. W., Novianti, K. R. & Roz, K. Work from home: Measuring satisfaction between work–life balance and work stress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Economies 9(3), 96 (2021).

Weng, Q. & Zhu, L. Individuals’ career growth within and across organizations: A review and agenda for future research. J. Career Dev. 47(3), 239–248 (2020).

Ragin, C. C. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond (University of Chicago press, 2009).

Spector, P. E. Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences (Sage publications, 1997).

Schermerhorn, J. R. Jr., Osborn, R. N., Uhl-Bien, M. & Hunt, J. G. Organizational Behavior (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

Zhang, Y. & Duan, X. Job demands, job resources and postdoctoral job satisfaction: An empirical study based on the data from 2020 Nature global postdoctoral survey. PLoS ONE 18(11), e0293653 (2023).

Nerad, M. & Cerny, J. Postdoctoral patterns, career advancement, and problems. Science 285(5433), 1533–1535 (1999).

Nordling, L. Postdoc career optimism rebounds after COVID in global Nature survey. Nature 622(7982), 419–422 (2023).

Wild, S. Leaving academia for industry? Here’s how to handle salary negotiations. Nature 616(7957), 615–617 (2023).

Yang, L., Cai, W., Wang, W. & Wang, C. How work affects the mental health of postdocs?—an analysis based on nature’s 2020 global postdoc survey data. Int. J. Mental Health Promot. 27(4), 421–449 (2025).

Albert, C., Davia, M. A. & Legazpe, N. Job satisfaction amongst academics: The role of research productivity. Stud. High. Educ. 43(8), 1362–1377 (2018).

Zhou, Y. & Volkwein, J. F. Examining the influences on faculty departure intentions: A comparison of tenured versus nontenured faculty at research universities using NSOPF-99. Res. High. Educ. 45, 139–176 (2004).

Rosser, V. J. & Townsend, B. K. Determining public 2-year college faculty’s intent to leave: An empirical model. J. High. Educ. 77(1), 124–147 (2006).

Ryan, J. F., Healy, R. & Sullivan, J. Oh, won’t you stay? Predictors of faculty intent to leave a public research university. High. Educ. 63, 421–437 (2012).

Van Benthem, K., Nadim Adi, M., Corkery, C. T., Inoue, J. & Jadavji, N. M. The changing postdoc and key predictors of satisfaction with professional training. Stud. Grad. Postdr. Educ. 11(1), 123–142 (2020).

Hagedorn, L. S. Conceptualizing faculty job satisfaction: Components, theories, and outcomes. New Dir. Inst. Res. 2000(105), 5–20 (2000).

Case, S. S. & Richley, B. A. Gendered institutional research cultures in science: The post-doc transition for women scientists. Community Work Fam. 16(3), 327–349 (2013).

Van der Weijden, I., Teelken, C., de Boer, M. & Drost, M. Career satisfaction of postdoctoral researchers in relation to their expectations for the future. High. Educ. 72, 25–40 (2016).

Stanford, M. et al. A Postdoctoral Crisis in Canada: From the ‘“Ivory Tower”’ to the Academic ‘“Parking Lot”’ (Canadian Association of Postdoctoral Scholars, 2009).

Teelken, C. & Van der Weijden, I. The employment situations and career prospects of postdoctoral researchers. Empl. Relat. 40(2), 396–411 (2018).

Faupel-Badger, J. M., Nelson, D. E. & Izmirlian, G. Career satisfaction and perceived salary competitiveness among individuals who completed postdoctoral research training in cancer prevention. PLoS ONE 12(1), e0169859 (2017).

Davis, G. Improving the postdoctoral experience: An empirical approach. In Science and Engineering Careers in the United States: An Analysis of Markets and Employment (ed. Davis, G.) (University of Chicago Press, 2009).

Guo, Y., Tian, Y. & Cai, N. Why do postdoctoral fellows intend to leave? An empirical analysis based on a global survey. Curr. Psychol. 43(38), 30211–30220 (2024).

López-Núñez, M. I., Rubio-Valdehita, S., Diaz-Ramiro, E. M. & Aparicio-García, M. E. Psychological capital, workload, and burnout: what’s new? the impact of personal accomplishment to promote sustainable working conditions. Sustainability 12(19), 8124 (2020).

Scaffidi, A. K. & Berman, J. E. A positive postdoctoral experience is related to quality supervision and career mentoring, collaborations, networking and a nurturing research environment. High. Educ. 62, 685–698 (2011).

Bozeman, B. & Gaughan, M. Job satisfaction among university faculty: Individual, work, and institutional determinants. J. High. Educ. 82(2), 154–186 (2011).

Moors, A. C., Malley, J. E. & Stewart, A. J. My family matters: Gender and perceived support for family commitments and satisfaction in academia among postdocs and faculty in STEMM and non-STEMM fields. Psychol. Women Q. 38(4), 460–474 (2014).

Grinstein, A. & Treister, R. The unhappy postdoc: a survey based study. F1000Research 6, 1642 (2018).

Woodside, A. G. Moving beyond multiple regression analysis to algorithms: Calling for adoption of a paradigm shift from symmetric to asymmetric thinking in data analysis and crafting theory. J. Bus. Res. 66(4), 463–472 (2013).

Herzberg, F., Mausner, B. & Synderman, B. S. The Motivation to Work (Wiley, 1959).

Herzberg, F., Mausnes, B., Peterson, R. O. & Capwell, D. F. Job Attitudes; Review of Research and Opinion (Psychological service of Pittsburgh, 1957).

Chen, C. Y. Are professors satisfied with their jobs? the factors that influence professors’ job satisfaction. SAGE Open 13(3), 21582440231181516 (2023).

Lacy, F. J. & Sheehan, B. A. Job satisfaction among academic staff: An international perspective. High. Educ. 34(3), 305–322 (1997).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55(1), 68 (2000).

Hackman, J. R. & Oldham, G. R. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 16(2), 250–279 (1976).

Kraus, S., Ribeiro-Soriano, D. & Schüssler, M. Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) in entrepreneurship and innovation research–the rise of a method. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 14, 15–33 (2018).

Fiss, P. C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 54(2), 393–420 (2011).

Ragin, C. C. The Comparative Method: Moving beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies (University of California Press, 2014).

Ordanini, A., Parasuraman, A. & Rubera, G. When the recipe is more important than the ingredients: A qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) of service innovation configurations. J. Serv. Res. 17(2), 134–149 (2014).

Rihoux, B. & Ragin, C. C. Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques (Sage, 2009).

Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H. & Ryan, R. M. Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psych. Organ. Behav. 4, 19–43 (2017).

Battaglio, R. P., Belle, N. & Cantarelli, P. Self-determination theory goes public: experimental evidence on the causal relationship between psychological needs and job satisfaction. Public Manag. Rev. 24(9), 1411–1428 (2022).

Marshall, D. M. A Qualitative Study of the Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors Contributing to Job Satisfaction and Profession Longevity in University Research Administrators (Capella University, 2015).

Shin, J. C. & Jung, J. Academics job satisfaction and job stress across countries in the changing academic environments. High. Educ. 67(5), 603–620 (2014).

Mgaiwa, S. J. Academics’ job satisfaction in Tanzania’s higher education: The role of perceived work environment. Soc. Sci. Hum. Open 4(1), 100143 (2021).

Miller, J. M. & Feldman, M. P. Isolated in the lab: Examining dissatisfaction with postdoctoral appointments. J. High. Educ. 86(5), 697–724 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XB conceptualized the study, analyzed the data, and drafted & revised the manuscript. XW discussed preliminary results with XB and provided feedback on the first and final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bing, X., Wan, X. Configurational impact of motivational factors on postdoctoral job satisfaction. Sci Rep 15, 41146 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24859-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24859-y