Abstract

Natural gas peak-shaving through seasonal liquefaction and storage provides an effective solution to mitigate fuel supply disruptions and improve energy security in power generation. This study presents the design and multi-domain optimization of a liquefied natural gas (LNG) production cycle using a mixed refrigerant (MR) system. The proposed cycle is optimized thermodynamically and economically, making it adaptable to a wide range of gas-fired power plants. A genetic algorithm (GA) is applied to minimize specific energy consumption (SEC), with the optimization process directly coupled to Aspen HYSYS® (Aspen Technology, Inc., Version 11, https://www.aspentech.com/en/products/engineering/aspen-hysys) simulations for accurate thermodynamic modeling. The framework simultaneously evaluates energy, exergy, and economic performance by optimizing refrigerant composition, pressure levels, and flow rates. The methodology is demonstrated through a case study of the Shahid Mofateh power plant in Iran, which experiences recurring natural gas shortages during winter. The GA-optimized configuration achieved a 12% reduction in SEC (from 0.37 to 0.31 kWh/kg), an exergy efficiency of 37%, and a coefficient of performance (COP) of 2.4. Economic analysis shows a net present value (NPV) of 4.2 million USD, an internal rate of return (IRR) of 13.1%, and a payback period of approximately 6.5 years. These results demonstrate that the proposed GA-based optimization framework is both technically effective and economically viable, and can be adapted for broader deployment in LNG-based peak-shaving systems across power plants with similar seasonal energy challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Iran is one of the largest natural gas reservoir owners and has a vast local distribution network. The high consumption of natural gas in cold seasons and the pressure drop of the natural gas pipeline leading to alternative fuels such as fuel oil, which has many environmental problems1,2. According to the Iranian Environmental Protection Organization, in February 2018, 440,000 barrels of fuel oil were burned daily in the power plants located in Iran, the ratio of energy to the natural gas volume at ambient pressure and the temperature is low; therefore, natural gas storage in hot seasons occupies a large volume. The solution is to reduce the natural gas temperature until it liquefies3,4.

In this study, the term “peak shaving” refers specifically to fuel supply peak shaving in gas-fired power plants, which differs from conventional electrical peak shaving. In regions like Iran, severe natural gas shortages occur during cold seasons due to high residential and industrial demand. As a result, power plants are often forced to switch to fuel oil, causing operational and environmental challenges. To mitigate this, natural gas is liquefied and stored during off-peak periods (typically summer), and regasified during peak winter months to maintain consistent fuel supply. This approach serves as a strategic energy storage solution, allowing the plant to reduce reliance on alternative fuels during seasonal gas supply constraints.

Natural gas liquefaction and storage near power plants or at the original distribution units can solve the lack of natural gas fuel in cold seasons. An essential challenge in expanding the liquid natural gas (LNG) industry is energy-consuming for the liquefaction cycle. Regasification, accompanied by heating and turning liquid into gas, causes a waste of energy. Various methods are used to minimize the power in compression parts of LNG processes5,6.

From the two methods of compression and liquefaction, the second method is more economical and safer to store natural gas. Natural gas liquefaction cycles reduce the gas temperature to the boiling point, and then it can be stored in cryogenic tanks7,8. Power consumption in the compression section of these cycles is the most critical parameter affecting the cycle efficiency in terms of economic aspects.

Nguyen et al.3 used mixed refrigerant methods in an LNG production cycle. They found the best composition of mixed refrigerants by optimization. Mehrpooya & Ansarinasab9 analyzed two simple mixed-component refrigerant processes by exergy and exergoeconomic analyses. They also explored the relationship between capital and operation costs and introduced the components with the highest cost of exergy destruction. They proposed an economic optimization method to examine exergoeconomic factors and exergy destruction cost; the method was based on sensitivity analysis.

Faramarzi et al.10 used exergy and economic analyses to reduce energy consumption and exergy destruction in light gases liquefaction systems including simultaneous production of LNG and liquid hydrogen. Khodaei et al.11 proposed a propane and butane gas liquefaction process. They utilized a genetic algorithm for optimization to minimize the power consumption in the compression part. Moradi et al.12 studied some LNG production cycles to store natural gas near power plants. They considered the properties of the required fuel capacity of different power plants in Iran to use them in a peak shaving system. They identified the key parameters and investigated the effect of the feed gas compositions on the environment.

Linde Company proposed LIMUM1 and LIMUM3 cycles to liquefy natural gas. The LIMUM3 process includes four stages of cooling at different temperatures. LIMUM3 is more complicated than LIMUM1, but The mixed refrigerant method is used in both cycles. LIMUM1 is used in low capacity LNG production processes, under 1600 TPD, while the performance of LIMUM3 is more appropriate in large capacity cycles13.

Aslambakhsh et al.14 optimized an LNG production system with a capacity of 50 tons per day by genetic algorithm method. Wang et al.15 experimentally studied a natural gas liquefaction process assisted by the mixed refrigerant method. They investigated the effect of temperature, pressures, and refrigerant flow compositions on the cycle performance.

Ghorbani et al.16 modified and examined a natural gas liquefaction system. They used advanced exergy and exergoeconomic analyses to identify the highest irreversible exogenous and endogenous devices. Khan and Lee17 studied a new refrigerant composition containing nitrogen, methane, ethane, and propane in a natural gas liquefaction process. By using a new LNG production system, they reduced the total power consumption in the cycle.

Recent research has highlighted the growing role of GA in optimizing LNG processes across both liquefaction and regasification domains. Lee18 applied GA to the multi-parameter optimization of a cascade Rankine cycle for LNG regasification, demonstrating that appropriate cycle configuration and working fluid selection (C₂C₂, C₃C₃, and C₂C₃) can significantly enhance cold energy recovery, achieving up to 96.3 kW of power generation with improved first-law efficiency. In liquefaction optimization, Furda and Variny19 introduced a parallel genetic algorithm interface (PAGAN) for the C3MR process, which enabled a seven-fold reduction in computation time and facilitated large-scale optimization runs that simultaneously minimized cost and CO₂ emissions. Extending these advances to hydrogen systems, Zhang et al.9 proposed a hybrid GA–SA algorithm for large-scale hydrogen liquefaction, which significantly reduced specific energy consumption, improved exergy efficiency, and achieved notable cost and emission reductions. Collectively, these studies underscore the versatility and robustness of GA-based methods and their hybrids in energy system optimization, forming the methodological foundation for the present work, which applies GA directly coupled with Aspen HYSYS simulations to optimize the thermodynamic, exergetic, and economic performance of an LNG peak-shaving cycle. While prior reviews such as Song et al.20 collate multiple mixed refrigerant liquefaction configurations and evaluate their thermodynamic performance—including specific power consumption—those studies do not extend to optimization under plant operating conditions, nor do they assess economic feasibility based on real cost data. In contrast, our work links GA optimization with high-fidelity HYSYS simulation for the Shahid Mofateh power plant, simultaneously optimizing energy, exergy, and the economic returns of the system.

While several researchers have applied optimization to LNG systems, most studies remain theoretical or simplified in scope. For instance, Shirazi and Mowla21 demonstrated ~ 13% reduction in energy consumption applying GA to an SMR process—but only in a simulated setting without economic performance metrics or real-plant data. Mehrpooya and Ansarinasab22 conducted exergoeconomic analysis on MR cycles, computing exergy destruction costs and sensitivity responses, yet without employing optimization or plant-scale application. Ghorbani et al.23 evaluated hybrid MR–absorption cycles, reporting reductions in specific power and capital cost—but again based purely on theoretical modeling. Other studies (e.g. Xu et al.24 optimized refrigerant composition for energy performance under idealized assumptions. In contrast, our work applies GA coupled with plant-specific simulations in Aspen HYSYS, optimized across energy, exergy, and economic domains, and validated for real-world implementation at the Shahid Mofateh plant.

Many studies are in the literature about natural gas liquefaction systems, but optimizing a natural gas fuel peak-shaving system for a power plant is a gap that can be studied more. The novelty of this study is based on two points: first, proposing and optimizing a new peak-shaving process which is designed for the Shahid Mofateh power plant as the case study. The optimization method is based on a genetic algorithm (GA), second, by using an appropriate mixed refrigerant fluid in the proposed peak-shaving system. There was no comprehensive economic analysis on peak-shaving systems; therefore, economic analysis is performed on the proposed cycle in this study. The main objective of the present study is the selection of a suitable peak-shaving system for a power plant. Fuel peak-shaving prevents replacing natural gas fuel with alternative fuels such as fuel oil and diesel. In this study, the fuel peak-shaving of the Shahid Mofateh power plant is investigated. Energy and exergy analyses are performed. The optimized cycle in this study can be used in peak-shaving systems and LNG production processes.

Characteristics of the process

Shown in Figs. 1 and 2 are two pictures of Shahid Mofateh power plant. Figure 1 shows the power plant on a day of winter 2021 when the power plant was using fuel oil instead of natural gas. It is crystal clear that harmful environmental effects occur by using fuel oil. The picture of the power plant in Fig. 2 was taken in spring 2021 when natural gas was used. It can be shown that there is no significant emission compared to that in Fig. 1.

Process description

Shahid Mofateh power plant has four units of 250 MW, and the total capacity of this power plant is 1000 MW. The efficiency is 45.4%. In this paper, the number of peak days is considered 60 days, and the number of non-peak days is 200 days based on the data from the reference1. Block diagrams of the power plant peak-shaving system are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. Figure 3 shows the non-peak condition, and Fig. 4 shows the peak condition.

177,668 tons of LNG is needed for the fuel peak-shaving system in the Shahid Mofateh power plant. Therefore, the capacity of this cycle should be 57,855 Kg/hour of LNG. The proposed cycle in this study is a modified liquefaction process assisted by the mixed refrigerant method. A combination of nitrogen and low boiling point hydrocarbons is used to reduce the power consumption of compressors. The higher heat transfer coefficient of the mixed refrigerant components decreases the needed refrigerant flow and reduces the total power consumption compared to using only nitrogen. On the other hand, the mixed refrigerant method increases the complexity of the process and equipment25. Figure 5 shows the proposed model, a deviation from the reference26.

According to Fig. 5, the NG-in stream passed four heat exchangers. It is liquefied by the mixed refrigerant cycle and reaches the ambient pressure by an expansion valve. Liquid and gas phases are separated in the separator. In the refrigerant part, three compressors and three air coolers are used in the compression unit. Table 1 shows the compositions of the main streams in the proposed cycle.

The MR cycle was chosen based on its superior performance in small- to mid-scale LNG systems. Compared to pure refrigerant and cascade systems, MR cycles offer better temperature glide control and improved heat transfer efficiency due to the use of components with varying boiling points. This allows closer temperature matching in the heat exchangers, significantly reducing exergy destruction and compression power. Additionally, MR cycles require fewer compression stages and lower capital investment, which makes them more practical for applications like seasonal peak-shaving. These benefits have been confirmed in prior comparative studies27.

Process simulation

Aspen HYSYS® (Aspen Technology, Inc., Version 11, https://www.aspentech.com/en/products/engineering/aspen-hysys) is used to simulate the process and component properties. Codes for GA is developed in MATLAB R2018b, and they are linked to Aspen HYSYS® (Aspen Technology, Inc., Version 11) to optimize critical parameters. Shown in Fig. 6 is the process simulation from this software. PR-EoS is suitable for the liquefaction of natural gas, mainly processes with mixed refrigerant systems. Morosuk et al.28 and Mehrpoya et al.29 used the PR-EoS method to simulate LNG production processes. In this research, Peng-Robinson equations of state (PR-EoS) predict single and mixed components properties. The constraints and simplifications in this study are considered as follows:

Methods

Energy, exergy and economic analysis

In the thermodynamic analysis, the energy consumption of the LNG liquefaction cycle is calculated and examined with two parameters, including SEC and COP, as follows34,35:

where \(Q_\epsilon\) is the heat taken from the cold flows in the heat exchangers. Exergy analysis is performed for the cycle, and the exergy of the streams, excluding the changes of kinetic and potential exergy, is considered as follows34,36 :

Process flow diagram of Aspen HYSYS® (Aspen Technology, Inc., Version, https://www.aspentech.com/en/products/engineering/aspen-hysys).

where \(\:{W}_{sh}\) is input power in the device, I exergy destruction, and \(\:{Ex}_{Qo}\) is heat transfer exergy, whereas subscripts “p” and “c” means physical and chemical exergy, respectively. Chemical exergy is neglected in this paper because no chemical reaction occurs in the process. Chemical exergy in this study is calculated based on the method of Kotas34,37. Shown in Table 2 are the exergy destruction and exergy efficiency equations for all components38.

An economic analysis is performed to examine the proposed cycles in terms of the CAPEX, OPEX, and O&M expenditures. Cost factors of CAPEX expenditure is shown in Table 3.

In this research, the total CAPITAL cost of liquefaction units is calculated as follows40,42:

The manufacturing cost of heat exchangers in an LNG production unit is based on the heat transfer surface area (A_Hex) and calculated as follows43,44:

The cost of a compressor is calculated as follows45:

where H is the work of the compressor, the amount of annual LNG is calculated as follows46:

where \(\:{Y}_{a}=0.95\) is the annual rate of cycle activity and \(\:{\dot{m}}_{LNG}\) is the mass flow rate of LNG (Serio et al., 2015). 200 working days are considered for the peak-shaving system. The annual cost of CAPEX, which is related to the value of annual interest rate (z) and payment period (t), is given as follows47:

OPEX expenditures include the cost of power consumption, the natural feed gas cost (\(\:{C}_{feed,a}\)), and charging refrigerants (\(\:{C}_{feedf,a}\)) due to gas leakage in cold boxes and pipes. Annual OPEX and O&M expenses are calculated as follows48:

where \(\:{c}_{el}\) is the cost of electricity for one kWh, \(\:{c}_{o\&M}\) the cost factor of operating and maintenance expenditure (\(\:{c}_{o\&M}\)) is assumed from 0.03 to 0.12 for simple and complex cycles, respectively47.

The economic model follows a life cycle cost (LCC) approach over a 10-year system life. Metrics such as NPV, IRR, and PBP are used to assess investment performance, based on annualized cash flow analysis and standard financial assumptions.

It is important to note that the optimization strategy in this study does not involve retrofitting or redesigning the heat exchangers. Instead, performance improvements were achieved through the adjustment of operating parameters (e.g., refrigerant composition and flow conditions) within the design limits of existing equipment. As such, CAPEX remains largely unchanged, and the economic benefits arise from reduction in operational losses, specifically the cost of exergy destruction. This reinforces the role of exergy-based cost evaluation as a key indicator of thermoeconomic improvement in existing systems.

To evaluate the long-term financial viability of the proposed LNG peak-shaving system, standard economic performance metrics were calculated, including net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), and payback period (PBP).

In line with standard exergoeconomic practice, benchmark values from comparable industrial energy system studies were reviewed to validate our economic assumptions. For instance, Galal et al.49 used an interest rate of 10%, a system lifetime of 25 years, and 8,000 operating hours per year as reference parameters. But the present study adopts a 10-year lifetime, 8% interest rate, and 4,800 operating hours/year, reflecting the seasonal and storage-based nature of LNG peak shaving in the Shahid Mofateh power plant context based on the reference20.

Cost assumptions included an electricity price of 0.06 USD/kWh50 and an average LNG market price of 350 USD/ton20. Using the previously estimated CAPEX, OPEX, and O&M, a discounted cash flow model was developed to quantify the economic return of the GA-optimized system.

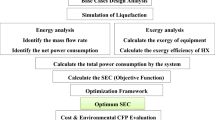

Genetic algorithm optimization

The GA method is based on iteration and genetic theory. The GA method is used to optimize the variables: pressure, mass flow rate, temperature, and percentage of mixed refrigerant components in this study. MATLAB R2018b software in conjunction with Aspen HYSYS® (Aspen Technology, Inc., Version 11, https://www.aspentech.com/en/products/engineering/aspen-hysys) is used for this purpose. Table 4 shows the variables and their range of variation. Additionally, to illustrate the impact of the GA optimization, Table 5 compares key design parameters—such as refrigerant composition, mass flow rate, and pressure—for the base case and the GA-optimized case. The adjustments in these variables directly contributed to performance improvements, including a 12% reduction in SEC and a noticeable decrease in exergy destruction, particularly in the heat exchanger Hex.P2.

The method of GA optimization for the present study is shown in Fig. 7. The GA method is based on the work of He and Lin [53], which is modified for the present study.

In this study, the GA optimization process was subject to a defined set of physical and design constraints to ensure the operational feasibility of the proposed LNG peak-shaving cycle. The key constraints included:

-

Fixed isentropic efficiency of compressors at 0.85.

-

No liquid phase permitted at compressor inlets.

-

Negligible pressure drop and heat loss in heat exchangers.

-

A minimum temperature approach in heat exchangers maintained between 1 °C and 3 °C.

-

Defined variable bounds for mole fractions, flow rates, and pressures (as shown in Table 4).

The GA optimization was validated using coupled simulations in Aspen HYSYS® (Aspen Technology, Inc., Version 11, https://www.aspentech.com/en/products/engineering/aspen-hysys), a trusted platform for cryogenic and LNG process modeling. Although experimental plant data were not available, the simulations were based on the real configuration and operating characteristics of the Shahid Mofateh power plant, providing a realistic and practically relevant framework for validation.

The genetic algorithm achieved convergence at the 97th generation, as shown in Fig. 8, which is earlier than the preset maximum of 200 generations. These parameters—population size of 80 and 200 maximum generations—were chosen based on sensitivity testing. Smaller values led to unstable convergence behavior, while larger values did not significantly improve results but increased computational cost.

A mutation rate of 0.05 was used to preserve diversity in the population and prevent premature convergence to local optima. A crossover fraction of 0.3 promoted exploration of the solution space, while tournament selection ensured that high-quality solutions were retained throughout the iterations. This configuration allowed the GA to effectively minimize SEC with reliable convergence and reasonable computational time (~ 67 min on an Intel i7 desktop with 16 GB RAM). Table 6 summarizes the GA configuration details.

As shown in Fig. 8, the curves decrease at the beginning because GA optimization find the better generation easier. The optimal generation number is 97.

In this study, SEC was selected as the sole objective function for optimization, due to its direct relevance to operational cost and system energy efficiency. While other indicators such as the COP or exergy efficiency were not explicitly optimized, they were evaluated after the GA convergence. The results showed a 6.6% increase in exergy efficiency and a corresponding reduction in exergy destruction, demonstrating that minimizing SEC also improved thermodynamic performance. This single-objective approach provided clear convergence behavior and effective guidance for design optimization within a practical context.

Results and discussion

The power consumed in the compression part is 18,629 kW. COP and Exergy efficiency is 2.4 and 0.37, respectively. Shown in Table 7 is the stream information of the proposed cycle.

Exergy destruction in heat exchangers and compressors is shown in Fig. 9. The total exergy destruction in the whole cycle is 11,743 kW. It is clear from Fig. 2 that the Hex.P2 heat exchanger has the highest exergy destruction among other devices. In the optimized case, the minimum temperature approach in heat exchangers is designed between 1 and 3, which reduces the exergy destruction in the heat exchangers compared to the base case.

Exergy destruction of Hex.p2 is 1631 in the optimized case. Figure 10 shows the exergy destruction in air coolers and expansion valves.

According to Figs. 9 and 10, it is clear that there is more exergy destruction in the heat exchangers than compressors, and air coolers have more exergy destruction than the expansion valves. Shown in Fig. 11 is the comparison of exergy efficiency between devices, including compressors and heat exchangers.

According to Fig. 11, the highest exergy and lowest exergy efficiency go to the heat exchanger (Hex.p3) and compressor (Com.p3), respectively. Figures 12 and 13 show a comparison of hot and cold composite curves in the heat exchanger (Hex.p4) for the GA optimized and base cases. The smaller the area between the two diagrams, the less exergy destruction in the heat exchangers occurs, leading to higher exergy efficiency in the heat exchangers and the whole cycle.

The minimum temperature approach decreased in all heat exchangers of GA optimized cases. The area between cold and hot composite curves was reduced in four heat exchangers. The exergy efficiency of the whole cycle is 37%. In the natural gas liquefaction cycles, the most effective devices in capital cost are heat exchangers and compressors. Figure 14 shows a comparison between the cost of heat exchangers, compressors and other components used in the proposed cycle.

According to Fig. 14, the cost of manufacturing of heat exchangers is 7.7 million dollars, while the manufacturing cost of compressors is 5.2 million dollars. The total manufacturing cost of all devices is 14.7 million dollars. Figure 15 compares the percentage of the manufacturing cost of compressors and heat exchangers. Shown in Fig. 16 is the annual cost of CAPEX, OPEX, and O&M expenditures. Shown in Fig. 17 is the comparison between different types of expenditures for the proposed cycle. According to Fig. 15, the cost of heat exchangers is 1.5 times higher than the cost of the compressors. Table 8 compares the SEC of the cycle in the present study and other works in the literate.

According to Table 8, the SEC of the cycle in this study is 3% less than that from reference [55] and 6% less than that of Perez and Diez [57]. COP is 2.4 for the GA optimized case, which is 2.2 for the base case. The lower the SEC of a cycle, the lower the power consumption required to produce a certain amount of LNG; thus, the cycle with lower SEC performs better in thermodynamic aspects and economic aspects. GA optimized case has the SEC value of 0.31, which is 12% less than that of the base case. An optimized cycle in this study can be used as a peak-shaving system in the Shahid Mofateh power plant.

In addition to thermodynamic improvements, the proposed system demonstrated strong economic performance based on a life cycle cost (LCC) analysis over a 10-year project period. Key economic indicators were used to evaluate investment viability, including net present value (NPV), Internal rate of return (IRR), and payback period (PBP). The results indicated an NPV of 4.2 million USD, an IRR of 13.1%, and a payback period of approximately 6.5 years, confirming the economic feasibility of the optimized LNG peak-shaving system under typical market conditions.

To assess financial robustness, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. A 20% increase in electricity prices caused the IRR to decrease to 10.2% and the payback period to extend to 7.5 years. In contrast, a 15% increase in refrigerant costs had a smaller impact, slightly lowering the NPV while maintaining profitability. These findings demonstrate that the system is not only energy-efficient but also economically resilient across realistic operating scenarios. The sensitivity analysis results are illustrated in Figs. 18 and 19, which show how IRR and PBP respond to changes in key input costs.

To better contextualize the contributions of this work, a comparative summary of similar studies in the field of LNG liquefaction system optimization is provided in Table 9. While several previous works have explored the use of genetic algorithms or refrigerant mixture tuning to improve energy efficiency, most of them remain either conceptual or simulation-based, without validation against real plant operations or economic feasibility. In contrast, this study presents an integrated optimization framework that simultaneously addresses energy, exergy, and economic performance, and is applied to a real-world case with verified operating data. The comparison below highlights the key differences in terms of optimization scope, SEC improvement, practical applicability, and inclusion of economic analysis.

Although this study is centered on the Shahid Mofateh power plant, the proposed peak-shaving framework has broad applicability to other gas-fired power stations facing similar seasonal fuel shortages. The methodology, including the use of a mixed refrigerant cycle, energy-exergy-economic evaluation, and genetic algorithm-based optimization, can be adapted to different operational scales and ambient conditions. For example, refrigerant composition and compressor operating pressures can be re-optimized for varying inlet gas properties, climate conditions, or plant capacities. The modular structure of the system also allows for integration with different types of existing infrastructure, making it suitable for retrofitting older facilities or planning new LNG-supported installations. Furthermore, since the model is built in Aspen HYSYS® (Aspen Technology, Inc., Version 11, https://www.aspentech.com/en/products/engineering/aspen-hysys) and MATLAB, it can be extended to perform scenario analyses for other power plants with different economic constraints or gas supply profiles. This flexibility positions the framework as a transferable solution for decentralized peak-shaving strategies beyond the specific context of Shahid Mofateh.

For instance, in a colder climate such as that of a northern European power plant, the refrigerant composition could be re-optimized by increasing the propane fraction by approximately 5–10%. This adjustment would improve the cycle’s thermodynamic matching under lower ambient temperatures, thereby enhancing efficiency and reinforcing the adaptability of the proposed framework across diverse climatic conditions.

Conclusion

Main findings and contributions

This study presented a modified LNG-based peak-shaving system tailored for the Shahid Mofateh power plant in Hamadan, Iran, to address the recurring challenge of natural gas shortages during the cold season. The system was designed to liquefy natural gas during off-peak (summer) periods and regasify it during high-demand (winter) periods to avoid reliance on fuel oil and reduce operational costs and emissions. The liquefaction cycle used a mixed refrigerant configuration, chosen for its flexibility and thermodynamic efficiency under partial load conditions.

The proposed system was modeled using Aspen HYSYS® (Aspen Technology, Inc., Version 11,

https://www.aspentech.com/en/products/engineering/aspen-hysys), and its performance was enhanced through single-objective optimization using a GA implemented in MATLAB. The objective function targeted the minimization of SEC, a critical indicator of energy efficiency and operational cost. Key decision variables included the mole fractions of the mixed refrigerant components, system pressures, and flow rates.

The optimization achieved a 12% reduction in SEC, from 0.37 to 0.31 kWh/kg_LNG, and increased the COP to 2.4. Exergy analysis showed that second law efficiency improved by 6.6%, and exergy destruction was significantly reduced in critical components such as the primary heat exchanger (Hex.P2). These improvements were achieved without altering the physical configuration of the plant, indicating the practicality of the solution for retrofitting existing systems.

Economically, the optimized system showed strong viability. A full 10-year life cycle analysis was performed, calculating key metrics including NPV of 4.2 million USD, IRR of 13.1%, and a PBP of 6.5 years. Sensitivity analysis further confirmed the robustness of the system under fluctuating market conditions, with profitability maintained even under higher electricity or refrigerant costs.

Comparison with similar systems in the literature demonstrated that the proposed GA-optimized cycle achieved superior performance, especially in terms of energy consumption and operational efficiency. Importantly, the optimization strategy focused on modifying operational parameters within existing hardware constraints, enabling both economic and technical feasibility without major capital investments.

In summary, this work offers a validated and cost-effective LNG peak-shaving solution suitable for real-world deployment in seasonal fuel-constrained power plants. It demonstrates the value of integrating thermodynamic modeling, exergy analysis, and advanced optimization techniques for improving system performance and financial outcomes simultaneously.

Suggestions for future works

While this study demonstrated the technical and economic viability of an LNG-based peak-shaving system optimized through genetic algorithms, several areas remain for future exploration. Multi-objective optimization approaches, incorporating second-law efficiency or total exergy cost alongside SEC, could yield more balanced solutions. In addition, dynamic modeling and real-time control strategies would help address transient operating conditions and enhance system adaptability.

Further research may also consider pilot-scale implementation for validation under real operating conditions, integration with renewable energy sources for improved sustainability, and broader application to other power plants with varying climatic or demand profiles. Including environmental metrics such as carbon emissions or life cycle emissions would provide a more comprehensive assessment of the system’s long-term impact.

Statements and Delarations.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CAPEX:

-

Capital expenditure

- COP:

-

Coefficient of performance

- EoS:

-

Equation of state

- FOM:

-

Figure of merit

- LNG:

-

Liquid natural gas

- OPEX:

-

Operation expenses

- O&M:

-

Operating and maintenance expenditure

- SEC:

-

Specific energy consumption

- PR:

-

Peng Robinson

- \(\alpha\) :

-

Pressure cost factor 1

- \(\alpha\) :

-

Pressure cost factor 1

- \(\beta\) :

-

Pressure cost factor 2

- \(\eta\) :

-

Exergy efficiency

- a:

-

Annual

- ac:

-

Actual

- c:

-

Chemical

- i:

-

In

- o:

-

Out

- P:

-

Physical

- rev:

-

Reversible

- \(A_{Hex}\) :

-

Heat transfer surface area(m2)

- \({C_{CAPEX}}\) :

-

Capital cost ($)

- \({C_{OPEX}}\) :

-

Cost of operation($)

- \({C_{O\& M}}\) :

-

Operating and maintenance expenditures($)

- Ccom :

-

Cost of compressors($)

- Cdel :

-

Delivery cost($)

- \(C_{Hex}\) :

-

Cost of heat exchangers($)

- \(C_{oth}\) :

-

Cost of other devices($)

- \({C_{tur}}\) :

-

Cost of turbines($)

- EX:

-

Exergy(KW)

- e:

-

Exergy(KW)

- \(e_{ph}\) :

-

Physical exergy(KW)

- \({f_{p,hex}}\) :

-

The pressure cost factor

- h:

-

Specific enthalpy (Kj/Kg)

- H:

-

Work of compressor or turbine(KW)

- \(\dot{m}_{LNG}\) :

-

The mass flow rate of LNG(Kg/h)

- \(P_{net}\) :

-

Total power consumption (kW)

- \(Q_{CV}\) :

-

Heat transfer (kW)

- I:

-

Exergy destruction(kW)

- S:

-

Specific entropy(\(Kj/K{g^ \circ }C\))

- t:

-

Payment period(year)

- \(\:W\) :

-

Work(kW)

References

Faramarzi, S., Mousavi Nainiyan, S. M., Mafi, M. & Ghasemiasl, R. Genetic algorithm optimization of two natural gas liquefaction methods based on energy, exergy, and economy analyses: the case study of Shahid Rajaee power plant peak-shaving system. Gas Process. 9 (1), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.22108/GPJ.2021.126527.1097 (2021).

Bedakhanian, A. & Assareh, E. Exploring an innovative approach to hydrogen generation for fuel cell energy production by integrating a dual organic Rankine system with an absorption chiller powered by geothermal energy. Energy Nexus. 13 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nexus.2023.100267 (2024).

Van Nguyen, T., Rothuizen, E. D., Markussen, W. B. & Elmegaard, B. Thermodynamic comparison of three small-scale gas liquefaction systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 128 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.09.055 (2018).

Faramarzi, S., Esmat, P., Karimi, E. & Abdollahi, S. A. Energy, exergy, economic, and sensitivity analyses of an enhanced liquid hydrogen production cycle within an innovative multi-generation system. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 149 (8). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-024-12895-1 (2024).

Shi, G., Wang, J. & Gates, I. D. Investigation of enhanced geothermal system in the basal cambrian sandstone Unit, Alberta, Canada. Heliyon 10 (2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24763 (2024).

Szczygiel, I. & Bulinski, Z. Overview of the liquid natural gas (LNG) regasification technologies with the special focus on the Prof. Szargut’s impact. Energy 165, 999–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.10.031 (2018).

Zhao, B. et al. Rollover mechanism methodology of LNG tank with gas-liquid stratification based on curvelet finite element method and large eddy simulation technology. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 11 (3). https://doi.org/10.29252/jafm.11.03.27796 (2018).

Tai, N. & Gates, I. D. Cyclic CO2 storage and geothermal energy extraction using a Huff and puff technique in the basal cambrian sandstone Unit, Canada. Geothermics 118 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geothermics.2024.102925 (2024).

Mehrpooya, M. & Ansarinasab, H. Exergoeconomic evaluation of single mixed refrigerant natural gas liquefaction processes. Energy Convers. Manag. 99 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2015.04.038 (2015).

Faramarzi, S., Nainiyan, S. M., Mafi, M. & Ghasemiasl, R. Proposing a simultaneous production cycle of liquid natural gas and liquid hydrogen, in The 29th Annual International Conference of the Iranian Association of Mechanical Engineers and the 8th Conference on Thermal Power Plants, Tehran, Iran, (2021).

Khodaee, M., Ashrafizadeh, A. & Mafi, M. Optimization of propane and Butane gas liquefaction cycle considering compressor technical limitations using genetic algorithm. Modares Mech. Eng. 17 (2), 315–324 (2017).

Moradi, K. M. & Mafi, A. Sensitivity analysis of peak-shaving natural gas liquefaction cycles to environmental and operational parameters. Modares Mech. Eng. 15 (6), 1027–5940 (2015).

Mazaheri, K., Nejati, A. & Kiani, K. C. The application of Suction and blowing in performance improvement of transonic airfoils with shock control bump. Scientia Iranica. 24 (1). https://doi.org/10.24200/sci.2017.4032 (2017).

Aslambakhsh, A. H., Moosavian, M. A., Amidpour, M., Hosseini, M. & AmirAfshar, S. Global cost optimization of a mini-scale liquefied natural gas plant. Energy 148, 1191–1200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.01.127 (Apr. 2018).

Wang, Q. et al. Experimental studies on a natural gas liquefaction process operating with mixed refrigerants and a rectifying column. Cryogenics (Guildf). 99 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cryogenics.2019.02.007 (2019).

Ahmadnejad, A., Ebrahimi, A. & Ghorbani, B. Pinch and exergy assessment of an innovative hydrogen and methane purification process configuration based on solar renewable energy. Fuel 359 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.130391 (2024).

Khan, M. S. & Lee, M. Design optimization of single mixed refrigerant natural gas liquefaction process using the particle swarm paradigm with nonlinear constraints. Energy 49 (1), 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2012.11.028 (Jan. 2013).

Song, Q. et al. Development of natural gas liquefaction processes using mixed refrigerants: a review of featured process configurations and performance, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.A1900143

Shirazi, M. M. H. & Mowla, D. Energy optimization for liquefaction process of natural gas in peak shaving plant. Energy 35 (7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2010.03.018 (2010).

Ghorbani, B., Mehrpooya, M., Shirmohammadi, R. & Hamedi, M. H. A comprehensive approach toward utilizing mixed refrigerant and absorption refrigeration systems in an integrated cryogenic refrigeration process. J. Clean. Prod. 179 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.109 (2018).

Xu, X., Liu, J. & Cao, L. Optimization and analysis of mixed refrigerant composition for the PRICO natural gas liquefaction process. Cryogenics (Guildf). 59, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cryogenics.2013.11.001 (Jan. 2014).

Zoulalian, A. Biomass position for renewable energies: main ways of energetic valorization. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.36884/jafm.3.01.11878 (2010).

Pérez, S. & Díez, R. Opportunities of monetising natural gas reserves using small to medium scale LNG technologies, in International Gas Union World Gas Conference Papers, (2009).

Wu, X., Wang, Z., Dai, X., Ge, Q. & Liu, F. Optimization design and analysis of Single-Stage mixed refrigerant liquefaction process. Front. Energy Res. 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2021.766588 (2021).

Morosuk, T., Tesch, S., Hiemann, A., Tsatsaronis, G. & Bin Omar, N. Evaluation of the PRICO liquefaction process using exergy-based methods. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 27 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2015.02.007 (2015).

Mehrpooya, M., Sadaghiani, M. S. & Hedayat, N. A novel integrated hydrogen and natural gas liquefaction process using two multistage mixed refrigerant refrigeration systems, Int J Energy Res, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 1636–1653, Mar. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/er.4978

Marmolejo-Correa, D. & Gundersen, T. A comparison of exergy efficiency definitions with focus on low temperature processes. Energy 44 (1), 477–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2012.06.001 (2012).

Hai, T. et al. Techno-economic-environmental study and artificial intelligence-assisted optimization of a multigeneration power plant based on a gas turbine cycle along with a hydrogen liquefaction unit. Appl. Therm. Eng. 237 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2023.121660 (2024).

Taghavi, M. & Lee, C. J. Development of novel hydrogen liquefaction structures based on waste heat recovery in diffusion-absorption refrigeration and power generation units. Energy Convers. Manag. 302 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2023.118056 (2024).

Sun, Z., Zheng, X. & Linghu, Z. Flow characteristics of a pipe diffuser for centrifugal compressors. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 10 (1). https://doi.org/10.18869/acadpub.jafm.73.238.26476 (2017).

Kotas, T. J. Exergy analysis of simple processes, in The Exergy Method of Thermal Plant Analysis, Elsevier, 99–161. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-408-01350-5.50011-8. (1985).

Gadhiraju, V. Cryogenic Mixed Refrigerant Processes. In International Cryogenics Monograph Series (Springer New York, 2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-78514-1

Faramarzi, S., Nainiyan, S. M. M., Mafi, M. & Ghasemiasl, R. A novel hydrogen liquefaction process based on LNG cold energy and mixed refrigerant cycle. Int. J. Refrig. 131, 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2021.07.022 (Jul. 2021).

Mafi, M., Naeynian, S. M. M. & Amidpour, M. Exergy analysis of multistage cascade low temperature refrigeration systems used in olefin plants. Int. J. Refrig. 32 (2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2008.05.008 (2009).

Timmerhaus, K. D. Cryogenic process engineering. Encyclopedia Phys. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/b0-12-227410-5/00156-3 (2003).

Javadi, M. A., Hoseinzadeh, S., Khalaji, M. & Ghasemiasl, R. Optimization and analysis of exergy, economic, and environmental of a combined cycle power plant, Sadhana - Academy Proceedings in Engineering Sciences, vol. 44, no. 5, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12046-019-1102-4

Cardella, U., Decker, L. & Klein, H. Roadmap to economically viable hydrogen liquefaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 42, 13329–13338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.01.068 (May 2017).

Faramarzi, S., Nainiyan, S. M. M., Mafi, M. & Ghasemiasl, R. Energy, exergy, and economic analyses of an innovative hydrogen liquefaction process utilising liquefied natural gas regasification system. Int. J. Exergy. 38 (4), 442–456. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijex.2022.124614 (2022).

Faramarzi, S., Gharanli, S., Ramazanzade Mohammadi, M., Rahimtabar, A. & Chamkha, A. J. Energy, exergy, and economic analysis of an innovative hydrogen liquefaction cycle integrated into an absorption refrigeration system and geothermal energy, Energy, vol. 282, p. 128891, Nov. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENERGY.2023.128891

Mafi, M., Amidpour, M. & Naeynian, S. M. M. Development in Mixed Refrigerant Cycles Used in Olefin Plants, in Proceedings of the 1st Annual Gas Processing Symposium, Doha, Ghatar, (2009).

Faramarzi, S. & Khavari, A. An innovative mixed refrigerant hydrogen liquefaction cycle to store geothermal energy as liquid hydrogen. J. Energy Storage. 72, 108008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.108008 (2023).

Dokandari, D. A., Khoshkhoo, R. H., Bidi, M. & Mafi, M. Thermodynamic investigation and optimization of two novel combined power-refrigeration cycles using cryogenic LNG energy, International Journal of Refrigeration, vol. 124, pp. 167–183, Apr. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2020.12.019

Serio, L. et al. CERN experience and strategy for the maintenance of cryogenic plants and distribution systems, in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, (2015). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/101/1/012140

Couper, J. R. Process Engineering Economics (CRC, 2003). https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203911396

Cardella, U., Decker, L., Sundberg, J. & Klein, H. Process optimization for large-scale hydrogen liquefaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 42 (17), 12339–12354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.03.167 (Apr. 2017).

Galal, M., El Maksoud, R. A. & Bayomi, N. N. Exergoeconomic analysis of a steam turbine power plant in a sulfuric acid factory. Results Eng. 24, 103330. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RINENG.2024.103330 (Dec. 2024).

He, T. & Lin, W. Design and analysis of dual mixed refrigerant processes for high-ethane content natural gas liquefaction. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 29, 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjche.2020.09.019 (Jan. 2020).

Ghorbani, B., Hamedi, M. H., Amidpour, M. & Shirmohammadi, R. Mise En place d’un cycle de froid par absorption à La place des cycles DMR et C3MR Dans La structure intégrée NGL, LNG et NRU. Int. J. Refrig. 77, 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2017.02.030 (May 2017).

Lee, S., Long, N. V. D. & Lee, M. Design and optimization of natural gas liquefaction and recovery processes for offshore floating liquefied natural gas plants. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51 (30). https://doi.org/10.1021/ie2029283 (2012).

Perry’s chemical engineers’ handbook,. Choice Reviews Online, 38, 02, doi: https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.38-0966. (2000).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the research and development (R&D) department of Shahid Mofateh power plant and special thanks to MAPNA group (TUGA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Seyyed Amirreza Abdollahi: Conceptualization, simulation, methodology, data analysis, writing—original draft. Arash Nourbakhsh Sadabad: Methodology, data collection, formal analysis, writing—review & editing. Seyyed Amirreza Mousavi Alamdardehi: Investigation, data validation, writing—review & editing. Naser Aslani: Data curation, software implementation, visualization. Reza Zarezadeh: Formal analysis, resources, writing—review & editing. Hamid Majidi: Supervision, project administration, final manuscript review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdollahi, S., Sadabad, A.N., Alamdardehi, S.A.M. et al. Genetic algorithm optimization of a modified peak shaving energy storage system with mixed refrigerant system. Sci Rep 15, 41134 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24873-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24873-0