Abstract

Musa balbisiana peel, a largely underutilized by-product, is konwn as a source of bioactive compounds. This study aims to investigate the extraction of polyphenols and saponins from M. balbisiana peel by microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) combined with optimized extraction conditions by response surface methodology (RSM). In addition, the biologically active constituents in the extract were also determined. Phytochemical screening and quantification revealed that the peel extract was rich in polyphenols and saponins, with total polyphenol content (TPC) and total saponin content (TSC) of 48.82 mg GAE/gDM and 57.18 mg/gDM, respectively, under optimal conditions (81.09% solvent concentration, 4.39 s/min irradiation cycle, 44.54 min microwave time). FT-IR and Raman spectroscopy confirmed the presence of characteristic functional groups of polyphenols and saponins. The purified fraction contained oleanolic acid, which was identified as the major compound after improving the extract’s purity. These findings provide insights into the chemical composition to explain the biological activity of M. balbisiana peel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Musaceae family includes Musa balbisiana, which is common in countries with tropical climates. Its parts are commonly known to contain high levels of polyphenols, flavonoids, tannins and saponins—secondary compounds with potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and inhibitory activities of many enzymes involved in many disorders in the body1,2. M. balbisiana peel has hypoglycemic properties in both in vitro and in vivo models3, as well as the ability to inhibit the enzymes tyrosinase, xanthan-oxidase, and lipase, which are related to skin disorders, gout and obesity4. M. balbisiana fruit contains high levels of polyphenols and saponins, which demonstrate great antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-MCF-7 breast cancer cell properties5,6. Dwiana Savitri et al. demonstrated that M. balbisiana peel extract has anti-inflammatory effects against acne vulgaris by suppressing nodule formation, inhibiting bacterial growth, and decreasing proinflammatory cytokine production7. Thus, it is necessary to study to improve the efficiency of obtaining extracts rich in bioactive substances from M. balbisiana peel, as well as to determine the chemical components to provide a basis for explaining the biological activities of banana peel extracts.

To overcome the disadvantages of traditional extraction methods, such as maceration or Soxhlet, which consume a lot of time, energy and solvent and have limited efficiency, the microwave-assisted extraction method (MAE) is increasingly popular in research to obtain extracts rich in bioactive substances8. Shijarath et al. found the optimal conditions for obtaining polyphenol and tannin-rich extracts from banana peel by microwave-assisted aqueous extraction and demonstrated the effectiveness of this method9. Anal et al., Musa acuminata peel was used as the material for polyphenol extraction. The results showed that M. acuminata peel is a rich source of phenolic compounds with strong antioxidant activity, contributing to slowing down the oxidation process in fish oil. The obtained extracts showed potential in inhibiting lipid oxidation in fish oil, suggesting the possibility of application as a natural antioxidant in the food industry10. In short, MAE is a nonconventional technique that offers a highly efficient, green extraction approach that reduces processing time and solvent consumption while maintaining the stability of heat-sensitive compounds, demonstrating broad applicability in both functional food and medicinal plant studies11.

M. balbisiana is a common plant species in Vietnam and has been used in traditional medicine for ages. However, they are not particularly valuable in daily life. Despite the extensive research on Musa sp., there is a notable lack of systematic studies on the extraction of bioactive compounds, such as polyphenols and saponins, from M. balbisiana peel using microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), as well as on comprehensive characterization of its chemical composition and the relationship between its constituents and biological activities. To address this gap, the present study investigated and optimized MAE conditions to obtain extracts with high total polyphenol content (TPC) and total saponin content (TSC) using response surface methodology (RSM). The functional groups present in the extracts were characterized through FT-IR and Raman spectroscopy, and the extracts were fractionated to identify the predominant compound in the purified fraction via NMR analysis. The findings provide optimized extraction parameters, detailed chemical profiles, and insights into the biological compounds of M. balbisiana peel extracts, highlighting the species’ potential as a valuable source of natural bioactives for applications in pharmaceuticals and functional foods.

Materials and methods

Materials

M. balbisiana peel was collected in An Hoa ward (Tam Nong district, Dong Thap province, Vietnam), collected from fruit reaching about 80–85% ripeness and harvested from the tree after about 115–120 days from flowering. The peel was cleaned, sliced, and dried at 60 °C12 to a moisture content below 10% before being ground into particles of less than 80 mesh. The powder was stored in a sealed bag at 4 °C and used for all experiments4.

Chemicals: Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, gallic acid (Merck). Chemicals and standards used in the study were of analytical grade and sourced from Merck and Sigma Andrich.

Methods

Phytochemical screening

The phytochemical screening of M. balbisiana peel was conducted using the following procedure. The peel powder was soaked sequentially in solvents at a raw material-to-solvent ratio of 1:20 (w/v) using distilled water, 80% methanol (v/v), and 80% ethanol (v/v) for 24 h at room temperature with constant shaking. All mixtures were passed through Whatman No. 1 filter paper. The resulting filtrates were analyzed for phytochemical screening to determine bioactive compound groups, including saponins, alkaloids, tannins, terpenoids, glycosides, anthocyanins, steroids, flavonoids, and polyphenols (Table 1).

Effects of microwave-assisted extraction on bioactives from Musa balbisiana peel

1 g of raw material (according to dried mass) and add MeOH solvent with investigated concentrations (40, 50, 60, 70, 80%) before adjusting the raw material/solvent ratio to 1/30 w/v. Then, the sample was treated with investigated powers (90, 180, 270, 360 and 540 W) for the intervals of 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 min with the investigated microwave irradiation cycle of 2, 3, 4, 5 s/min. Then, the sample continued to be incubated in a 60 °C thermostatic bath for 60 min. After treatment, residue was removed from the mixture by filtering, and then UV–Vis photometry (Genesys 10S UV–VIS, Thermo Scientific, USA) was used to determine TPC and TSC.

Optimization of the extraction by response surface methodology (RSM)

Screening experiments: Conduct screening experiments to determine the influence of four factors: solvent concentration (%), microwave power (W), microwave irradiation cycle (s/min), and microwave time (min). Minitab 19 software was used to construct the experimental matrix and analyze experimental data. The parameters provided by the data processing results indicate the level of influence of each factor.

Optimization experiments: The RSM method was used to investigate the optimal extraction conditions. The optimal experimental Box Behnken (BBK) was chosen for the design experiments. The experimental matrix was established using JMP 10 software with 03 factors and 03 levels (-1, 0, + 1). From four investigated factors, namly solvent concentration (%), microwave power (W), microwave irradiation cycle (s/min), and microwave time (min), three variables exhibiting the most significant effects on the extraction process were identified through preliminary screening and subsequently selected for optimization. The dependent variables (response variables) were total polyphenol content (Y1, mgGAE/gDM) and total saponin content (Y2, mg/gDM). The full quadratic regression is represented in the following equation (Eq. 1).

where Y is the predicted response, β0, βi, βii, and βij are the regression coefficients for the intercept, linear, quadratic and interaction terms, and Xi and Xj are the independent variables. The experimental results obtained by the BBK design will be imported and analyzed using the JMP 10 software.

FT-IR, Raman, NMR spectra determination

The M. balbisiana peel extract was purified preliminarily via a liquid–liquid extraction process with petroleum ether (PE), then n-butanol-water to eliminate impurities such as lipids and pigments. After obtaining the solution, FT-IR and Raman spectra were determined. FT-IR spectrum of the peel extract was recorded on a Tensor 37 Brucker (Bruker Optics, USA) with a KBr beam detector in the absorption mode of 400–4000 cm−116. The Raman spectrum of the peel extract was recorded on a Raman Cora 5X00 spectrometer (Anton Paar, USA). The obtained fractions were continued to be subject to silica gel column chromatography with the elution solvent system of chloroform: methanol (A), ethyl acetate: n-hexane (B), chloroform—n-hexane (C) to collect the fraction with higher TPC and TSC content. The purity was checked by TLC (Thin Layer Chromatography). The purified fraction was determined by the 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR nuclear magnetic resonance spectra on a Bruker Advance DPX-500 NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Berlin, Germany). Purified samples were ultrasonically treated at 75.5 MHz and 27℃, then dissolved in D2O at a concentration of 20 μg/mL for 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectroscopy17.

Analytical methods

Determination of saponin content (TSC): TSC was determined according to the method of Chen et al.18. The results were expressed in mg/gDM. Saponin content was calculated according to the formula:

Cx is the saponin concentration from the standard curve; V is the volume of extract (mL); F is the dilution factor; and m is the mass of dry matter in the raw material sample (g).

Determination of total polyphenol content (TPC): TPC was quantified by the Folin-Ciocalteu method based on the study of Feduraev et al. (2019). The absorbance was measured at 765 nm19. Total polyphenol content was calculated by the formula:

where: TPC (mg gallic acid/g dry mass), a is the value from the standard curve with gallic acid (µg/mL); V is the volume of extract solution (mL), and m is the mass of dry matter in the raw material sample (g).

The content of flavonoid (TFC), alkaloid (TKC), tannin (TTC), steroid content (TStC), anthocyanin (TAC), and carotenoid (TCC) was determined via UV–Vis spectrophotometry methods. TFC was determined by the colourimetric method as described by Chlopicka et al.20. TKC was based on the UV–Vis spectrophotometric method and the reaction of alkaloids with bromocresol green (BCG) to determine total alkaloid content; Atropine was used in the standard curve21. TTC was determined, and tannin content was performed according to the method of Tambe et al.22. TStC was determined by tetrazolium according to the Vietnamese Pharmacopoeia V23. TAC was determined using the differential pH method. In principle, anthocyanin pigments undergo reversible structural changes with pH changes, which are manifested by different absorption spectra. When pH = 1.0, the colour in the oxonium form predominates, and the colourless hemiketal forms predominate at pH = 4.524. TCC was determined as described by Kotíková et al.25.

Data analysis

Experiments were arranged in 3 replicates, and the results are presented as mean ± SD. Experimental data were analyzed using SPSS Statistic 20 (IBM Corporation), Minitab 19 (Minitab, LLC) and JMP 10 (SAS Institute Inc.) software systems. Duncan’s new multiple-range tests were used to determine mean differences, and results were considered significant at p < 0.05. Graphs were drawn using Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corporation).

Results and discussion

Phytochemical screening and quality analysis of bioactive compounds

Phytochemical screening was performed as described in Sect. “Phytochemical Screening”. The groups of substances giving characteristic colour results with the reagents were further quantified. The results are presented in Table 2.

From the results of Table 2, it can be seen that the anthocyanins and steroid tests appeared with unclear signals. The saponins, polyphenols, tannins, and flavonoid compounds appeared with distinct characteristics shown through the observed colour intensity. The extract from M. balbisiana peel contains a higher content of saponin and polyphenol, with 36.06 mg/gDM (TSC) and 28.09 mgGAE/gDM (TPC), in particular. The extraction efficiency is attributed to the interaction between the solubility of the solvent and the target compounds. It becomes necessary to study and evaluate the appropriate solvent for each material’s structure and composition since each part has its own unique structure and composition26. Polar solvents such as ethanol and methanol are more effective in extracting bioactive substances than water or non-polar solvents such as hexane. This is also confirmed by previous studies on the recovery of bioactive substances from plants, such as polyphenols and flavonoids. Because their derivatives are often polar (containing many phenol groups in the structure) and, therefore, dissolve better in polar solvents than in non-polar solvents27. The use of aliphatic alcohols (methanol, ethanol) and polar organic solvents (acetone, ethyl acetate) is the most common choice for extracting polyphenols and saponins from plant substrates28.

Thus, the phytochemical screening and quantitative results of active ingredients in M. balbisiana peel extract in different solvents (methanol, ethanol, and distilled water) indicate that the methanol solvent resulted in higher extraction efficiency than ethanol and water. In addition, the polyphenol and saponin content was higher than that of other active ingredients, so TPC and TSC were chosen as target objects for further extraction experiments.

Effects of microwave-assisted extraction method on obtaining polyphenols and saponins-rich extracts from Musa balbisiana peel

The effects of solvent concentration, microwave power, microwave irradiation cycle and extraction time on the extraction efficiency to obtain an extract rich in polyphenols and saponins are presented in Table 4. The experimental results showed that 70% methanol was a suitable solvent concentration for obtaining an extract rich in TPC and TSC from M. balbisiana peel. Solvent concentration has a great influence on the extraction process, such as extraction efficiency, extraction rate, and the compounds to be extracted. As the solvent concentration increases, cell penetration accelerates, and the extraction of natural compounds becomes easier. The structure of the desired compounds can be damaged by a solvent concentration that is too high, leading to a reduction or loss of biological activities. In contrast, low solvent concentration can result in poor extraction efficiency because saturation has not been reached, leading to poor ability to pull substances out of the sample. Microwave power can also change the extraction equilibrium and mass transfer conditions, affecting the release of polyphenols and saponins. The suitable power for extracting polyphenols and saponins from M. balbisiana peel was 270 W. At higher power, the extraction efficiency of the extract is significantly reduced. This phenomenon occurs because the microwave power is too high, causing the chemical decomposition of bioactive compounds in the extract. Therefore, the extraction efficiency of antioxidants obtained from TSC and TPC was lower. The report of I. Hismath et al. showed that increasing microwave power is related to an increasing temperature at a certain level that can simultaneously decompose the polyphenol compounds that have been collected or even break down the polyphenol structure that remains in the plant cells. Besides, it also causes the solvent to evaporate, increasing the cost of the research process29.

It can be seen that the general trend of increasing the microwave time from 20 to 40 min is accompanied by an increase in TPC and TSC of M. balbisiana peel extract. After 40 min, the extraction efficiency gradually decreased, which explains that the extract has reached a final equilibrium between the solute concentration in the raw material and the solution according to Fick’s second law of diffusion. Extending the time may result in degradation of phenolic compounds due to exposure to oxygen. Another report by Liu et al. optimized the extraction conditions of flavonoids from sweet potato leaves (SPL) with a raw material/solvent ratio (1/40, w/v), using 72% ethanol as solvent at 57 °C for 76 s, obtaining the highest flavonoid extraction efficiency of 91.65 ± 3.37%30. This finding suggests that optimizing extraction parameters, such as temperature, solvent concentration, and time, is crucial for maximizing yield, with an optimal duration beyond which compound degradation or equilibrium limits further improvement.

Several studies have shown that the percentage of extraction yield tends to increase with increasing microwave frequency in the MAE method; however, higher exposure to microwave power may cause the degradation of bioactive compounds8. Therefore, the selection of an appropriate microwave irradiation cycle in MAE is necessary to achieve high recovery in quality and quantity. Based on the results from Fig. 1, the extraction efficiency of TSC and TPC compounds was investigated at different microwave irradiations ranging from 2 to 5 s/min. At the irradiation from 2 to 4 s/min, the TSC and TPC changed significantly and reached the highest level at 4 s/min. However, the TSC and TPC content obtained tended to decrease significantly at 5 s/min. This may be due to the decomposition of biological compounds when the sample is exposed to microwave radiation for a long time. The results obtained from this study are consistent with the report of N.V. Tang et al. (2017), who also chose the microwave frequency level of 4 s as the optimal parameter for MAE to extract saponin from Phyllanthus amarus31.

Finally, the extraction efficiency from M. balbisiana peels increased with the increase in microwave time from 20 to 40 min. However, when the time was extended to 60 min, the TPC and TSC tended to decrease. This shows that increasing the extraction time did not increase TPC, and TSC recovered because the amount of the polyphenol and saponin of the raw material was fixed. On the other hand, the longer the microwave treatment time, the amount of polyphenols and saponin, which are sensitive to high temperatures, were exposed to heat for a longer time, so some of them would be decomposed, leading to a decrease in TPC and TSC values32.

Thus, the selection of the extraction process parameters, which included methanol 70%, power 270 W, microwave irradiation cycle of 4 s/min and microwave treatment time of 40 min was chosen from these experiments. The extraction method using intermittent microwaves combined with a methanol incubation at 60 °C for 60 min after microwave treatment in this study may have produced a synergistic effect in enhancing the recovery of bioactive compounds from M. balbisiana peel. Microwave energy disrupts the complex lignocellulosic structure of banana peel, weakens the cell wall, and increases the contact between the solvent and the material. The incubation process after microwave treatment further facilitates the penetration of methanol into the plant tissue, thereby more effectively solubilizing compounds such as polyphenols and saponins. The combination of physical (microwave) and chemical (solvent incubation) extraction processes may have resulted in higher extraction yields than either method alone. The incubation process after microwave treatment further facilitated the penetration of methanol into the plant tissue, thereby more effectively dissolving compounds such as polyphenols and saponins. The combination of microwave and solvent incubation extraction processes may have resulted in higher extraction yields than either method alone. Further studies are needed to clarify the influence of parameters such as temperature, incubation time, and solvent polarity on this synergistic effect.

Optimizing the extraction

Screening experiment design

The purpose of the screening experiment was to discover the primary effects and interactions of the investigated factors on polyphenols and saponins extraction from M. balbisiana peel. A 2-level full factorial experimental design was utilized in the study, which involved four influencing factors: solvent concentration (X1), microwave power (X2), microwave irradiation cycle (X3), and microwave time (X4). The results are presented in Fig. 2.

The influence of solvent concentration, microwave power, irradiation cycle and time was calculated using Minitab 19 software. The TPC and TSC in the extract were significantly affected by solvent concentration, microwave irradiation cycle, and microwave time, as demonstrated by the results. Thus, the three factors that had the greatest influence were chosen for optimal experimental design.

Optimizing experimental design

The optimal conditions were determined by constructing and applying separate quadratic polynomial regression models for each reaction in this study. Through initial screening experiments, three factors that significantly affected TPC and TSC were selected for optimizing MAE conditions with two objectives. These factors were coded as X1, X2, and X3, respectively, which correspond to three experimental levels: − 1, 0, and +1. Specifically, the levels set for X1 (methanol concentration) were 70%, 80% and 90%, respectively; X2 (irradiation cycle) 3, 4 and 5 s/min; and X3 (microwave time) 30, 40 and 50 min. The extraction efficiency was analyzed by constructing the RSM and analyzing the influence of each factor using this code in the experimental design. The JMP 10 software was used to analyze the experimental data according to the established model (Table 3). The analysis findings showed that the independent variables have linear and square effects, interact with each other, and have regression coefficients (Table 4).

The good fit of the model is indicated by the R2 value in the range of 0.8–0.933. Moreover, the F value of lack of fit (p > 0.05) is used to evaluate the model’s fit. The analysis of variance values requires significant values to make the model empirical (p < 0.05).

From the results in Table 4, the polynomial equation has the following form after removing coefficients without statistically significant meaning.

It can be discerned from the regression equation (Y1, Y2) that most factors have a certain influence on the objective function. After conducting ANOVA analysis using JMP, with the peel extract containing TPC, TSC reached a maximum at 48.82 mgGAE/gDM, 57.18 mg/gDM, respectively, when extracted under the following conditions: methanol 81.09%, microwave irradiation cycle 4.39 s/min, microwave time 44.54 min. The RSM demonstrates how the investigated factors affect TPC and TSC, and the model that predicts optimal conditions is simulated in Fig. 3.

Optimization process verification: the experiment was carried out under optimized conditions (repeated 3 times). The experimental TPC and TSC results were 47.49 ± 0.43 (mgGAE/gDM), 54.95 ± 0.21 (mg/gDM), respectively, compared to the predicted values of 48.82 (mgGAE/gDM) and 57.18 (mg/gDM), respectively. This result differed by < 5%, indicating that the experimental saponin content did not differ significantly from the content predicted by the quadratic regression model.

Raman and FT-IR spectroscopic characterization of preliminary purified extracts from M. balbisiana peel

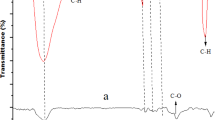

A preliminary purified M. balbisiana extracts were spectroscopically analyzed using Raman and FT-IR techniques to determine its major phytochemical constituents. The Raman spectrum of the extract of M. balbisiana peel displays a series of vibrational bands characteristic of both saponins and polyphenols. Peaks observed at approximately 264 , 402 and 470 cm −1 are attributed to skeletal C–C vibrations within cyclic or fused-ring systems, which are structural features typical of the oleanane-type triterpenoid core present in many saponins34,35. A distinct peak at 827 cm−1 corresponds to β-anomeric vibrations associated with glycosidic linkages, indicative of saponin structures wherein sugar moieties are covalently attached to aglycones such as oleanolic acid36. Supporting this assignment, the band at ~ 1035 cm−1 is consistent with C–O stretching vibrations in glycosidic bonds and polyhydroxylated systems, characteristic of both saponins and polyphenols37. The presence of polyphenolic compounds is further supported by a cluster of bands in the 600–850 cm−1 and 1200–1650 cm−1 spectral regions. Specifically, peaks at 677 and 726 cm−1 correspond to aromatic C–H out-of-plane bending vibrations, typically associated with phenolic compounds such as flavonoids and phenolic acids38. Additional evidence for aromatic functionalities includes bands at 1216 and 1261 cm−1, attributed to C–O–C and phenolic ring deformations, respectively, and a prominent band at approximately 1657 cm−1, indicative of C = C stretching in conjugated aromatic systems39. Collectively, these features strongly suggest the presence of flavonoid-type polyphenols, which are common constituents of plant secondary metabolites (Fig. 4).

The FT-IR spectrum further corroborates the Raman spectroscopic findings. A broad and intense absorption band at 3494 cm−1 signifies a high density of hydroxyl groups, key functional groups in both polyphenols and the sugar moieties of saponins. The peak at 2939 cm−1 is assigned to aliphatic C–H stretching, primarily arising from CH₂ and CH₃ groups within the hydrophobic triterpenoid backbone of saponins. A carbonyl stretching band at 1690 cm−1 is indicative of carboxylic acid functionalities. In the fingerprint region, absorption bands at 1210, 1091, and 1033 cm−1 correspond to C–O and C–C stretching modes associated with carbohydrate residues and ether linkages, consistent with the structures found in both saponins and polyphenols. The sharp band at 826 cm−1 further supports the presence of β-glycosidic linkages. Additionally, bands at 1459 and 1386 cm−1 are attributed to CH₂ and CH₃ bending vibrations, reinforcing the presence of a saturated hydrocarbon framework, characteristic of triterpenoid saponins with out-of-plane bending of aromatic C–H bonds and glycosidic linkages40, confirming the co-existence of polyphenolic and saponin structures within the extract. Notably, oleanolic acid—a triterpenoid saponin aglycone—exhibited a 77.3% spectral match when comparing the FT-IR spectrum of the extract with reference library spectra, providing strong evidence for the presence of saponins (Fig. 5).

NMR spectroscopic characterization of purified fraction from M. balbisiana peel extract

The structure of the isolated compound was elucidated based on a detailed analysis of its 1H and 13C NMR spectra in DMSO-d₆. The data are in excellent agreement with those reported for the pentacyclic triterpenoid oleanolic acid (C₃₀H₄₈O₃), a well-characterized natural product widely found in medicinal plants. The 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra of the compound called VC in the purified fraction isolated from M. balbisiana peel extract are presented in Figs. 5 and 6.

In the 1H-NMR spectrum, a key diagnostic resonance appears at δ 5.15 ppm (1H, t, J = 3.7 Hz), characteristic of the olefinic proton at C-12. This signal confirms the presence of a Δ12(13) double bond, a structural hallmark of the oleanane-type triterpenoid skeleton. Additionally, a broad singlet at δ 11.13 ppm corresponds to a carboxylic acid proton, indicating the presence of a free carboxylic acid group at the C-28 position. The high-field region (δ 0.70–1.20 ppm) contains multiple singlets and doublets attributable to methyl groups, consistent with the seven methyl substituents typically found in the oleanane framework. These include methyl groups at positions C-23 through C-27, as well as C-29 and C-30, located on tertiary and quaternary carbons of the triterpenoid backbone. The 13C-NMR spectrum further supports the structural assignment. A downfield resonance at δ 179.03 ppm is attributed to the carboxylic acid carbon at C-28. Two prominent signals at δ 122.0 and 144.3 ppm correspond to sp2-hybridized olefinic carbons at C-12 and C-13, respectively, consistent with the Δ12(13) unsaturation. The remaining 27 carbon signals fall within the expected chemical shift ranges for aliphatic methyl groups (δ ~ 15–32 ppm), methylene/methine carbons (δ ~ 20–60 ppm), and oxygenated or bridgehead quaternary carbons (δ ~ 70–80 ppm). Notably, a resonance at δ 78.0 ppm is assigned to the C-3 carbon bearing a hydroxyl group, another diagnostic feature of oleanolic acid. A detailed comparison of all proton and carbon chemical shifts with literature data (Table 5)41. Taken together, the 1H and 13C NMR data, in conjunction with previously reported spectral characteristics, strongly support the identification of the isolated compound VC as oleanolic acid. The proposed structure of this compound is presented in Fig. 7 and 8.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that Musa balbisiana peel is a rich source of bioactive compounds, with saponins and polyphenols as the predominant constituents. MAE was shown to be an effective method for obtaining extracts enriched in these compounds, and the optimized extraction conditions were established via the RSM method. Structural characterization using FT-IR and Raman spectroscopy confirmed the presence of characteristic functional groups, while NMR analysis identified oleanolic acid as the major triterpenoid in the purified fraction. These findings highlight the potential of M. balbisiana peel as a natural source of bioactive compounds for applications in pharmaceuticals and functional foods. Further studies on the biological activities of the extracts should be carried out to support their targeted use in specific products and to expand the knowledge base for practical applications.

Data availability

The corresponding author is willing to share the data supporting the findings of this study upon reasonable request.

References

Nelson, S. C. & Ploetz, R. C. Kepler AK Musa Species (Banana and Plantain) (Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry, 2006).

Swargiary, A. et al. Phytochemistry and pharmacological property of Musa balbisiana Colla: A mini-review. Pharmacogn. Rev. 15(29), 91–95. https://doi.org/10.5530/phrev.2021.15.11 (2021).

Hoang, T. N. N. et al. Comparative study on the hypoglycemic effects of different parts of Musa balbisiana. Food Sci. Nutr. 12(12), 10347–10356. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.4573 (2024).

Nhon, H. T. N. et al. The inhibition activity on tyrosinase, xanthine oxidase, and lipase of Musa balbisiana parts grown in Vietnam. Food Sci. Nutr. 12(10), 7428–7437. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.4364 (2024).

Nhon Hoang, T. N. et al. Phytochemical screening, extraction, and determination of the bioactivities of the extract-enriched polyphenols and saponins from Musa balbisiana fruit. J. Food Process. Preserv. 203, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/2581641 (2023).

Huyen N. T. T. et al. Anti-Lipase and MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation Inhibition in Vitro of the Extract-Enriched Polyphenols and Saponins from Musa balbisiana fruit. Tạp chí Khoa học Đại học Công Thương. 24(1) (2024). https://doi.org/10.62985/j.huit_ojs.vol24.no1.24.

Savitri, D. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of banana (Musa balbisiana) peel extract on acne vulgaris: In vivo and in silico study. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 18(6), 1586–1598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2023.07.008 (2023).

Chizoba Ekezie, F.-G. et al. Microwave-assisted food processing technologies for enhancing product quality and process efficiency: A review of recent developments. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 67, 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2017.05.014 (2017).

Shijarath, T. R. et al. Microwave assisted aqueous extraction of phenolic compounds from pomegranate and banana peels: Process modelling and optimization. Food Humanit. 3, 100456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foohum.2024.100456 (2024).

Anal, A. K., Jaisanti, S. & Noomhorm, A. Enhanced yield of phenolic extracts from banana peels (Musa acuminata Colla AAA) and cinnamon barks (Cinnamomum varum) and their antioxidative potentials in fish oil. J. Food Sci. Technol. 51(10), 2632–2639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-012-0793-x (2014).

Bagade, S. B. & Patil, M. Recent advances in microwave assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from complex herbal samples: A review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 51(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408347.2019.1686966 (2021).

ElGamal, R. et al. Thermal degradation of bioactive compounds during drying process of horticultural and agronomic products: A comprehensive overview. Agronomy 13(6), 1580. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13061580 (2023).

Nhon, H. T. N. et al. Saponin extraction from inflorescence of Musa balbisiana. HUIT J. Sci. 25(1), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.62985/j.huit_ojs.vol25.no1.162 (2025).

Bhandary, S. K. et al. Preliminary phytochemical screening of various extracts of punica granatum peel, whole fruit and seeds. J. Health Allied Sci. NU 02(04), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1703609 (2020).

Shaikh, J. R. & Patil, M. K. Qualitative tests for preliminary phytochemical screening: An overview. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 8(2), 603–608. https://doi.org/10.22271/chemi.2020.v8.i2i.8834 (2020).

Hoa V. T. T., Khoi N. T. & Nhon H. T. N. Purification and characterization of fucoidan extracted from Ceratophyllum submersum algae. J. Sci. Technol. Food. 19(1), 104–113 (2019).

Palanisamy S. et al. Isolation of fucoidan from Sargassum polycystum brown algae: Structural Characterization, in Vitro Antioxidant and Anticancer Activity. 102, 405–412 (2017).

Chen, Y., Xie, M.-Y. & Gong, X.-F. Microwave-assisted extraction used for the isolation of total triterpenoid saponins from Ganoderma atrum. J. Food Eng. 81(1), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2006.10.018 (2007).

Feduraev, P. et al. Variation in phenolic compounds content and antioxidant activity of different plant organs from Rumex crispus L. and Rumex obtusifolius L. at different growth stages. Antioxidants 8(7), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox8070237 (2019).

Chlopicka, J. et al. Total phenolic and total flavonoid content, antioxidant activity and sensory evaluation of pseudocereal breads. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 46(2), 548–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2011.11.009 (2012).

V.L. Singleton, R Orthofer, & Lamuela-Raventós R., Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and sntioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. In: Methods in Enzymology. 299(1999), 152–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99017-1.

Tambe, V. D. & Bhambar, R. S. Estimation of total phenol, tannin, alkaloid and flavonoid in Hibiscus tiliaceus Linn. wood extracts. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2(4), 41–47 (2014).

Ministry of Health, Vietnam—Vietnamese Pharmacopoeia (2018).

Mónica G. M. & E. W. R., Characterization and measurement of anthocyanins by UV‐Visible Spectroscopy. Current Protocols in Food Analytical Chemistry. 00 (1) F1. 2.1-F1. 2.13. (2001) https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142913.faf0102s00.

Kotíková, Z. et al. Determination of antioxidant activity and antioxidant content in tomato varieties and evaluation of mutual interactions between antioxidants. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 44(8), 1703–1710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2011.03.015 (2011).

Kandasamy, S. et al. Antioxidant properties of isolated compounds from banana rhizome. J. Food Sci. 79(5), H988-1001. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.12414 (2014).

Qiu, Y., Liu, Q. & Beta, T. Antioxidant properties of commercial wild rice and analysis of soluble and insoluble phenolic acids. Food Chem. 121(1), 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.12.021 (2010).

Stalikas, C. D. Extraction, separation, and detection methods for phenolic acids and flavonoids. J. Sep. Sci. 30(18), 3268–3295. https://doi.org/10.1002/jssc.200700261 (2007).

Hismath, I., Aida, W. M. W. & Ho, C. W. Optimization of extraction conditions for phenolic compounds from neem (Azadirachta indica) leaves. Int. Food Res. J. 18, 931–939 (2011).

Liu, J. et al. Optimization of ultrasonic–microwave synergistic extraction of flavonoids from sweet potato leaves by response surface methodology. J. Food Process. Preserv. 43(5), e13928. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpp.13928 (2019).

Nguyen, V. T. et al. Microwave-assisted extraction as an advanced technique for optimization of saponin yield and antioxidant potential from Phyllanthus amarus. Sep. Sci. Technol. 52, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/01496395.2017.1374972 (2017).

Barve, K. H., Laddha, K. S. & Jayakumar, B. Extraction of saponins from safed musli. Pharmacogn. J. 2(13), 561–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0975-3575(10)80060-4 (2010).

Caporaso, N. et al. Effect of olive mill wastewater phenolic extract, whey protein isolate and xanthan gum on the behaviour of olive O/W emulsions using response surface methodology. Food Hydrocoll. 61, 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.04.040 (2016).

Brody, R. H., Edwards, H. G. & Pollard, A. M. Fourier transform-Raman spectroscopic study of natural resins of archaeological interest. Biopolymers 67(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/bip.10059 (2002).

Edwards, H. G. & Ali, E. M. Raman spectroscopy of archaeological and ancient resins: Problems with database construction for applications in conservation and historical provenancing. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 80(1), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2011.01.030 (2011).

Yu, M. M. et al. Raman microspectroscopic analysis of triterpenoids found in plant cuticles. Appl. Spectrosc. 61(1), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1366/000370207779701352 (2007).

Synytsya, A. Fourier transform Raman and infrared spectroscopy of pectins. Carbohyd. Polym. 54(1), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0144-8617(03)00158-9 (2003).

Movasaghi, Z., Rehman, S. & Rehman, I. U. Raman spectroscopy of biological tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 42(5), 493–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/05704920701551530 (2007).

Reitzenstein, S. et al. Nondestructive analysis of single rapeseeds by means of Raman spectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 38(3), 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.1643 (2006).

Lin-Vien, D. et al. The Handbook of Infrared and Raman Characteristic Frequencies of Organic Molecules (Elsevier, 1991).

Seebacher, W. et al. Complete assignments of 1H and 13C-NMR resonances of oleanolic acid, 18α-oleanolic acid, ursolic acid and their 11-oxo derivatives. Magn. Reson. Chem. 41(8), 636–638. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrc.1214 (2003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hoang Thi Ngoc Nhon: Conceptualization (lead), Investigation (equal), Methodology (lead), Writing review (lead) and Editing (lead). Luu Thi Quynh Hoa: Conceptualization (equal), Investigation (lead). Nguyen Van Anh: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal). Le Thi Hong Anh: Conceptualization (equal), Writing review (equal).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoang, T.N.N., Luu, T.Q.H., Anh Nguyen, V. et al. Optimization of extraction and structural characterization of bioactive compounds from Musa balbisiana peel. Sci Rep 15, 41031 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24874-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24874-z