Abstract

Climate change is a key driver of threats to global biodiversity; therefore, assessing its temporal and spatial impacts on endangered species and their habitats is crucial for developing adaptive conservation strategies. This study investigated the habitat dynamics of the endangered Hainan gymnure (Neohylomys hainanensis) by integrating ecological niche modelling using MaxEnt with geospatial analysis using ArcGIS. We considered ten climatic variables, three timepoints (current, 2055, and 2085), and three CO2 emission scenarios. The results showed that 1) the current potential suitable habitat area is 11,092.14 km2 (32.75% of Hainan Island), which is mainly distributed in central Hainan Island; 2) elevation (PC = 78.5%) and Bio1 (PI = 60.0%) are key environmental factors affecting the potential distribution of suitable habitat and have synergistic effects; 3) suitable habitats show shrinking trends under the three future climate scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, SSP5-8.5). Of note, annual average temperatures will significantly increase in the high-altitude areas under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, which will nearly eliminate suitable habitat areas. This study clarifies the geographical distribution range, key limiting factors, and future habitat change trends of N. hainanensis, thereby providing a scientific basis for the species’ adaptive conservation and management and offering reference data on the climate response mechanisms of tropical island species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climatic factors, particularly temperature and precipitation, play a crucial role in shaping the geographical distribution of species1. Global climate change is profoundly impacting Earth’s biodiversity and ecosystems2. Natural populations adapt to climate change through shifts in geographical distribution and alterations in growth and reproduction periods3. Although species exhibit significant variability in their responses to climate change4, the adaptive responses of many species may be insufficient to match the rapid pace and extensive scale of climate change, thereby increasing their vulnerability to population decline or even extinction5. If global temperatures rise to 1.5 °C above the pre-industrial average, almost a third of species worldwide could be at risk of extinction6. Therefore, understanding the impacts of climate change on species distributions holds critical ecological significance7.

Island ecosystems exhibit heightened vulnerability to climatic perturbations due to their geographic isolation, limited dispersal corridors, and high endemicity8. Climate change disrupts island ecosystems, causing habitat loss and fragmentation for animals, particularly endangered species, which increases the risk of species extinction9. Thus, assessing the potential impacts of climate change on island species distributions is crucial for formulating conservation strategies and mitigating extinction risks. Hainan Island (18°10′–20°10′N, 108°37′–111°03′E), located at the northern edge of the tropical zone, is bordered by the Qiongzhou Strait to the north and South China Sea to the south. Hainan is the second largest island in China and covered with the largest contiguous tropical rainforest in the country10. Thus, it is one of the regions with the highest biodiversity in China and a global hotspot for biodiversity research and conservation11,12,13.

The Hainan gymnure (Neohylomys hainanensis) is a small-bodied insectivorous species endemic to Hainan Island that belongs to the class Mammalia, order Eulipotyphla, and family Erinaceidae14. It primarily inhabits tropical rainforests at altitudes of 300–800 m15,16. This species is characterised by its limited mobility, and it primarily feeds on Coleoptera insects, with occasional consumption of grass and seeds17. Due to its limited population, the species was listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the China Biodiversity Red List18,19. Additionally, it has been designated as a key protected wild animal in Hainan Province. Previous research on N. hainanensis has focused on its morphology, chromosome karyotype, and taxonomic status15,20,21,22,23,24, while few studies have modelled its habitat suitability under climate change. This research gap is important to fill given the significant impacts of climate change on island ecosystems, which can lead to habitat loss and fragmentation for animals, especially endangered species. Therefore, investigating the habitat suitability dynamics of N. hainanensis under climate change is crucial for guiding conservation actions.

Species distribution models (SDMs) are used to construct the relationship between species distribution and environmental factors by using known distribution data of species and relevant environmental variables. By employing specific algorithms, SDMs can identify the ecological requirements of species and project the results into different temporal and spatial contexts to predict both the actual and potential distributions of species25,26,27. Among various SDM approaches, the MaxEnt model has been widely used due to its practical advantages, including user-friendly operation, mature algorithmic framework, and high predictive accuracy, even with limited occurrence data. Additionally, its robustness to parameter settings enhances its applicability across diverse studies28,29,30,31,32.

This study used the MaxEnt model and spatial analyses to predict the suitable habitats of N. hainanensis focused on Hainan Island, evaluate its habitat suitability, and identify the key environmental variables influencing its distribution. Furthermore, the spatial patterns of range contraction and expansion were delineated. To our knowledge, this is the first study to model the potential distribution of N. hainanensis under current and future climate scenarios on Hainan Island. By assessing the impacts of climate change on its distribution, our work provides a theoretical basis for the conservation and management of this species. Additionally, it addresses a critical research gap and offers new insights for the ecological management of N. hainanensis.

Materials and methods

Species occurrence data collection and processing

Geographical distribution point data for N. hainanensis were obtained based on (1) a field investigation conducted over the entirety of Hainan Island from March 2020 to February 2025 to record the longitude and latitude of N. hainanensis and (2) records from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) database33, which were accessed on December 17, 2024. A total of 38 occurrence records of N. hainanensis were collected (Fig. 1). To minimise spatial autocorrelation and sampling bias, occurrence points were spatially filtered using the ‘spThin’ package34 in R (version 4.5.0), thereby ensuring a minimum distance of 5 km between points. This process yielded 17 unique occurrence records for model computation.

Spatial distribution of occurrence records for N. hainanensis on Hainan Island. The administrative boundaries were obtained from the Resource and Environment Science and Data Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The map of species distribution was generated using ArcGIS 10.8 (https://rj.taizlkj.cn/cst/?s=arcgis&bd_vid=7243370671383874737).

Current and future environmental variables

Nineteen current biological climate variables (represented by the average values from 1981 to 2010) were obtained from the high-resolution climatology data of the Earth’s land surface area (CHELSA) database. These bioclimatic variables, primarily representing temperature, precipitation, and their seasonal variations35, were selected due to their biological significance and widespread application in species habitat prediction36,37. Elevation data were downloaded from the WorldClim version 2.1 database. Because no future elevation projections are available, we followed the common convention of assuming that elevation remains constant over the current one38. Land-cover projections for each SSP-PCP combination were obtained from the Global-SSP-RCP-LUCC Product (http://www.geosimulation.cn/Global-SSP-RCP-LUCC-Product.html) at a 1 km2 spatial resolution39. Climate and elevation layers were standardised to 0.5 arcmin. To minimise multicollinearity, pairwise Pearson correlations were computed among all bioclimatic variables, and correlated climate variables (|r|> 0.70) were sequentially removed40. Both the elevation and land-cover were incorporated into the modelling framework. After multicollinearity screening and variable selection, ten environmental variables were retained for the final simulation: annual mean temperature (Bio1), mean diurnal range (Bio2), annual precipitation (Bio12), precipitation of driest month (Bio14), precipitation seasonality (Bio15), precipitation of warmest quarter (Bio18), elevation (Elev), crop vegetation coverage (Crop), forest vegetation coverage (Forest), and non-forest vegetation coverage (Non-forest).

For future projections, three shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs) were selected: SSP1-2.6 (low emission scenario), SSP3-7.0 (medium emission scenario), and SSP5-8.5 (high emission scenario). To account for uncertainties in future climate projections, we utilised five global circulation models (GCMs): 1) Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory Earth System Model 4 (GFDL-ESM4), 2) Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace Climate Modeling System 6A-Low Resolution (IPSL-CM6A-LR), 3) Max Planck Institute Earth System Model 1.2—High Resolution (MPI-ESM1-2-HR), 4) Meteorological Research Institute Earth System Model 2.0 (MRI-ESM2-0), and 5) United Kingdom Earth System Model 1.0—Low Resolution (UKESM1-0-LL). Future projections were generated for two time periods based on the multi-model ensemble (MME) mean of the selected GCMs: 2055 (2041–2070 average) and 2085 (2071–2100 average). This approach helped mitigate intermodel variability and provided a more robust estimation of climate change impacts. Both current and future bioclimatic data were derived from the coupled model intercomparison project phase 6 (CMIP6).

Model simulation and evaluation

Model calibration is crucial for constructing robust models to identify the optimal parameter combinations that best represent the phenomenon through data fitting41. We optimised the MaxEnt model parameters using the ‘kuenm’ R package42. The model calibration process used the five available feature classes (FCs), namely, linear (L), quadratic (Q), product (P), threshold (T), and hinge (H), and tested 31 types and combinations: L, Q, P, T, H, LQ, LP, LT, LH, QP, QT, QH, PT, PH, TH, LQP, LQT, LQH, LPT, LPH, LTH, QPT, QPH, QTH, PTH, LQPT, LQPH, LQTH, LPTH, QPTH, and LQPTH. The regularisation multiplier (RM) values were set from 0.1 to 4.0 at 0.1 intervals. The optimal parameters were determined based on statistical significance, predictive performance, and model complexity. Statistical significance was evaluated based on a partial receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis43, predictive performance was assessed via omission rates44, and model complexity was quantified with the corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc). Model selection was also based on the AICc, where the optimal parameter combination corresponded to the lowest AICc value (delta AICc = 0)45. The optimal feature types and regularisation multiplier for the final MaxEnt model were determined through this optimisation process. The maximum number of background points was set to 10,000. Model calibration utilised 75% of occurrence records, with validation and assessment of the model’s predictive accuracy utilising the remaining 25%. Clamping settings were used during extrapolation to reduce uncertainties when the model is projected into new environmental conditions that were not encountered during the training phase46. Model robustness was enhanced by performing 10 replicate runs with cross-validation, and the logistic output format was selected, with all other parameters set to MaxEnt’s default values for consistency.

To mitigate stochastic variability and rigorously quantify model performance, we evaluated predictive accuracy with the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) and true skill statistic (TSS)47. AUC interpretation followed established benchmarks: ≤ 0.70 represents poor performance, 0.70–0.80 represents acceptable performance, 0.80–0.90 represents good performance, and > 0.90 represents excellent performance48,49. For TSS, we adopted the standard 0.5 threshold: grid cells with predicted probability ≥ 0.5 were classified as present, whereas those < 0.5 were classified as absent47,50,51.

To investigate the role of environmental variables in modelling, the study employed two widely used evaluation metrics in MaxEnt: percentage contribution (PC) and permutation importance (PI)52,53,54. PC quantifies the contribution of a variable to the model’s regularised gain during training, while PI measures the decrease in training AUC when the values of a variable are randomly permuted. Both metrics were normalised to percentages for ease of interpretation. Higher values of PC or PI indicate greater variable importance in the model55.

Classification of current suitable habitats

The MaxEnt prediction results were visualised and processed using ArcGIS 10.8 (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA), where the data were converted to raster format and reclassified into habitat suitability categories. In the screening model, the 10th percentile training presence logistic threshold (0.15), balance training omission, predicted area and threshold value (TPT) (0.30), and maximum training sensitivity and specificity (MTSS) (0.45) were used as classification thresholds. The output results of the MaxEnt model were then redivided into the following four categories: not suitable (0–0.15), low suitability (0.15–0.30), moderate suitability (0.30–0.45), and high suitability (0.45–1.0). The area of each suitability zone was calculated by counting the number of pixels and converting them to actual surface area56.

Dynamics in future suitable habitats

The 10th percentile training threshold was set as 0.15 for the logic rule, and the MaxEnt output was reclassified into a binary grid (1 = above 0.15, 0 = below 0.15). The 10th percentile training presence logistic threshold categorised fewer than 10% of the training presence locations as unsuitable habitat57. To further analyse the distribution changes of N. hainanensis, we used SDMtoolbox and binary suitability data to examine range shifts across Hainan Island under future environmental scenarios58. Areas were quantified as expanded, contracted, stable (unchanged regions), and unsuitable habitats. Additionally, changes in the geographic centroid of species distribution were calculated to illustrate the dynamic shifts over the coming decades.

Results

Accuracy evaluation of model prediction

Among the 1240 candidate models, a single parameter combination was retained, as shown in Supplemental Table S1 (regularisation multiplier = 1.9, feature class combination = QH). The optimal model exhibited a mean AUC ratio of 1.726, a partial ROC of 0, an omission rate of 0.25, and the lowest adjusted AICc of 329.942. Ten replicate runs yielded an average training AUC of 0.918 ± 0.016 and TSS of 0.641 ± 0.003, thus confirming the high predictive accuracy and reliability of the model for estimating the potential habitat suitability of N. hainanensis.

Current distribution prediction and key environmental factors

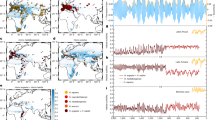

Under current climate conditions, the suitable habitat for N. hainanensis was primarily located in the central part of Hainan Island (Fig. 2). The total potential suitable habitat area was 11,092.14 km2, accounting for 32.75% of Hainan Island. Specifically, high-suitability habitat covered 5053.59 km2 (14.92%), and medium-suitability habitat covered 2090.61 km2 (6.17%). The medium–high-suitability habitat was predominantly found in the central-southern region of Hainan Island, while the low-suitability habitat was mainly found in the northern region (Fig. 2). The importance of the environment can be evaluated by the PC and PI values of the environment variables. The three most significant bioclimatic variables and their PC and PI were as follows: elevation (Elev, 78.5% and 23.3%), annual average temperature (Bio1, 12.3% and 60.0%), and non-forest vegetation coverage (Non-forest 2.2% and 0.9%). The cumulative PC and PI values of these three variables reached 93.0% and 84.2%, respectively (Table 1).

Simulated current habitat suitability for N. hainanensis in Hainan Island. These two maps were generated using ArcGIS 10.8 (https://rj.taizlkj.cn/cst/?s=arcgis&bd_vid=7243370671383874737) based on MaxEnt results.

Prediction of future suitable habitats of N. hainanensis on Hainan Island

Under future climate scenarios, the potential distribution areas of the three suitability classes (low, moderate, and high) exhibited significant changes. By 2055, suitable habitats were projected to decline by 44.18%, 54.84%, and 60.05% under the SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5 scenarios relative to the current conditions, respectively (Fig. 3). Moreover, changes in the suitable habitat areas of the three paths were similar and mainly concentrated in the northern and southeastern region of Hainan Island. By 2085, with increases in carbon dioxide emissions, the suitable habitat area of N. hainanensis showed a dramatic reduction towards the central part of Hainan Island. Particularly under the SSP5-8.5 climate scenario, the suitable habitat of N. hainanensis was nearly eliminated (reduced by 89.79%) (Fig. 3).

Potential distribution changes of N. hainanensis from the present to 2085 under the climate scenarios corresponding to the SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5 pathways. Maps were depicted using ArcGIS 10.8 (https://rj.taizlkj.cn/cst/?s=arcgis&bd_vid=7243370671383874737) based on MaxEnt results.

Dynamic changes of the suitable habitat range of N. hainanensis under future climate scenarios

Under the SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios, the centroid of the of N. hainanensis habitat is projected to shift consistently toward the south-western highlands of Hainan Island (Fig. 4). The magnitude of displacement scales with radiative forcing: in the low-warming SSP1-2.6 scenario, the centroid migrates only modestly; under the moderate-forcing SSP3-7.0 scenario, intensified warming and increasing extreme events drive an intermediate relocation; whereas in the high-forcing SSP5-8.5 scenario, severe climatic stress imposes the largest distributional shift, compelling the species to colonise increasingly remote, high-elevation refugia. Spatial analysis indicates that the habitat range shifts under SSP5-8.5 were more pronounced than those under SSP1-2.6 and SSP3-7.0.

Dynamic changes of potential suitable habitat areas for N. hainanensis on Hainan Island under the future climate scenarios. The map of dynamic changes of potential suitable habitat areas was depicted using ArcGIS 10.8 (https://rj.taizlkj.cn/cst/?s=arcgis&bd_vid=7243370671383874737).

Discussion

The MaxEnt model avoids the subjectivity of mechanistic models and the difficulty in obtaining input parameters of regression models, and it has higher prediction accuracy when dealing with a small number of samples29,59,60. However, the prediction performance of the model is constrained by the spatial aggregation degree of occurrence records. When these occurrence records are highly auto-correlated, the model overfits spatially redundant signals, yielding an inflated prediction that extends well beyond true distributional limits of the species61. This study involved 38 distribution points of N. hainanensis and selected the most representative and independent distribution points, thereby avoiding the problem of model overfitting. However, the potential distribution of N. hainanensis in this study may be absolutely accurate due to the limited sample size. The selection of environmental variables also determines the accuracy of the model’s prediction results62. Although environmental variables (climate data, altitude, and land cover data) were used to construct SDMs, additional microhabitat variables (slope, aspect, air relative humidity, and soil, etc.) were not included. Thus, the models may only approximate rather than precisely predict the species’ suitable habitats.

Furthermore, the resolution of climate data can affect the reliability of model prediction results63. This study utilised CHELSA v2.1 (with a resolution of 1 km) climate data, which can provide a macroscopic climate background for the islands. However, the coarse 1 km resolution smooths out the micro-climate gradients on the islands, thereby increasing the difficulty of identifying key habitats, such as micro-refuges, and potentially leading to incorrect predictions of the expansion or contraction of suitable areas in future scenarios. Based on the above analysis, future research should enhance the accuracy of predicting the species’ spatial distribution by supplementing species occurrence records, selecting more diverse environmental variables (especially microhabitat factors), and incorporating higher-resolution climate and land cover data.

In the present study, the potential distribution range of N. hainanensis was modeled using the MaxEnt and model performance was evaluated using two complementary metrics (AUC and TSS). The AUC values exceeded 0.9 and TSS values exceeded 0.5. This indicates that the model predictions of the potential distribution of N. hainanensis are highly accurate and thus and can provide a reference basis for formulating conservation strategies for this species.

The study demonstrated that the suitable habitats for N. hainanensis are predominantly located in central Hainan Island, which is highly consistent with historical distribution records from areas such as Jianfengling, Yinggeling, Wuzhishan, and Diaoluoshan and the counties of Baisha and Qiongzhong16,17,64,65,66. Notably, the medium and high suitability habitat areas were mainly located within the Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park in the central part of Hainan Island (Fig. 2). This pattern indicates that the species is highly dependent on tropical rainforest ecosystems, with its survival depending on stable humidity, dense understory vegetation, and specific food resources that are predominantly available in the park’s primary and secondary forests.

The species distribution model identified Elev as the primary driver of the potential range of N. hainanensis, accounting for 78.5% of the PC. This highlights the species’ strong dependency on mid- to upper-montane forest habitats in central Hainan (e.g. Wuzhishan, Limushan and Bawangling). However, the PI of Elev was only 23.3%, indicating that its independent contribution to predictive accuracy is modest. The discrepancy arises because elevation is strongly collinear with temperature and precipitation gradients; thus, the climatic variables capture a substantial proportion of the ecological signal encoded by elevation.

Among climatic variables, Bio1 emerged as the critical constraint, with a PI of 60%). For an endothermic small mammal, ambient temperature governs the energy consumption for maintaining body temperature and significantly affects the activity budgets67,68. Moderate montane temperatures therefore enhance the fitness and reproductive output of N. hainanensis. Temperature also indirectly impacts its populations by affecting its primary food source—Coleoptera insects17—whose propagation and distribution are temperature-restricted69,70. Notably, the PC of Bio1 was only 12.3%, signalling that temperature’s influence is not independent but rather is largely mediated by elevation, with the two predictors jointly affecting the species’ potential distribution.

Under all three future climate scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5), the potentially suitable habitat of N. hainanensis was projected to contract markedly. The magnitude of the habitat loss exhibited a pronounced positive relationship with both radiative forcing intensity and temporal horizon. First, compared to the mainland, the climate system of islands was more vulnerable to the effects of global warming71. In the future climate scenarios, the sensitivity of island climates amplified the pressure on habitat contraction72,73. Consequently, even the SSP1-2.6 scenario projected a 47.7% loss of climatically suitable habitat for N. hainanensis by 2085, whereas SSP5-8.5 projected a reduction of almost 90% (Fig. 3). Second, as a tropical island, Hainan Island has a unique climate characterised by high temperatures and high humidity, with significant vertical climate variations74,75. Due to elevation uplift, the high-altitude areas in the central region, due to the elevation uplift, have formed a cool and humid mountain climate, which is suitable habitat of N. hainanensis. Future climate warming may make cause some areas that were previously suitable for the species’ survival to become unsuitable, resulting in a reduction of suitable habitats and a migration toward higher latitudes or altitudes76,77,78. However, the island’s orographic ceiling (Wuzhishan peak = 1,867 m) provides only limited upslope refuge; thus, habitat loss will be severe. In addition, changes in the island’s climate (such as the intensification of extreme rainfall events occur under the SSP5-8.5 scenario) may lead to habitat fragmentation or loss.

Based on these findings, the following management suggestions are proposed: 1) Conduct systematic field surveys within and around Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park to better understand the distribution of N. hainanensis; 2) Reassess the conservation status of N. hainanensis, which was listed as an endangered species by IUCN in 2015; 3) Prioritise the protection of the current core suitable habitats, focus on establishing ecological reserves and connecting corridors in the high-altitude areas of central Hainan Island; 4) Concurrently advance low-carbon development pathways such as implementing emission-reduction policies, accelerating energy transitions, and alleviating long-term habitat pressure. These actions are crucial for the effectively conserving this endangered species amid ongoing climate change.

Conclusion

This study shows that the current suitable habitats of N. hainanensis (accounting for 32.75% of the entire island) are mainly distributed in central Hainan Island, such as Wuzhishan, Limushan, and Diaoluoshan. Elev and Bio1 jointly act as the key environmental factors influencing the potential distribution of N. hainanensis. Under all three future scenarios, the potential suitable habitats of N. hainanensis show a shrinking trend. In SSP1-2.6, the annual average temperature fluctuates smoothly and most of the potential suitable habitats in the middle and high-altitude areas are retained (47.67% of suitable habitats reduced by 2085). In SSP3-7.0, the imbalance of social development exacerbates climate disturbances, resulting in a habitat shrinkage in 2085 (suitable habitats reduced by 69.96%). In SSP5-8.5, unabated, high-end radiative forcing drives pronounced warming, culminating in an 89.8% loss of habitat by 2085.

This study reveals the geographical distribution range and spatial change trend of the main population of N. hainanensis under future climate conditions, and analyses the main environmental variables affecting its distribution. These findings can provide reference support for the adaptive management of this species and guidance for the subsequent research on the climate response mechanism of tropical island species.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wu, J., Xu, H. G. & Cheng, L. A. Review of impacts of climate change on species. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 27(04), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-4831.2011.04.001 (2011).

Weiskopfa, S. R. et al. Climate change effects on biodiversity, ecosystems, ecosystem services, and natural resource management in the United States. Sci. Total. Environ. 773, 137782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137782 (2020).

Hu, W., Onditi, K. O., Jiang, X., Wu, H. & Chen, Z. Modeling the potential distribution of two species of shrews (Chodsigoa hypsibia and Anourosorex squamipes) under climate change in China. Diversity 14(2), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14020087 (2022).

Moritz, C. et al. Impact of a century of climate change on small–mammal communities in Yosemite National Park. USA. Sci. 322, 261–264. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1163428 (2008).

Hoffmann, A. A. & Sgrò, C. M. Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature 470, 479–485. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09670 (2011).

Urban, M. C. Climate change extinctions. Science 386(6726), 1123–1128. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adp44 (2024).

Elith, J. & Leathwick, J. R. Species distribution models: Ecological explanation and prediction across space and time. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. S. 40, 677–697. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120159 (2009).

Barnett, J. Adapting to climate change in Pacific Island countries: The problem of uncertainty. World Dev. 29(6), 977–993. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00022-5 (2001).

Wetzel, F. T., Beissmann, H., Penn, D. J. & Jetz, W. Vulnerability of terrestrial island vertebrates to projected sea-level rise. Global Change Biol. 19, 2058–2070. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12185 (2013).

Yan, Q. L. et al. Impact of climate change on the potential distribution of wetland Landscape in Hainan Island based on MaxEnt Model. Wetland Sci. Manag. 20(3), 38–44. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-3290.2024.03.07 (2024).

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., Da Fonseca, G. A. & Kent, J. Biodiversity hot spots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858. https://doi.org/10.1038/35002501 (2000).

Shi, H. T. Retrieval of Terrestrial Vertebrates in Hainan (Hainan Publishing House, 2001).

Jiang, Z. G. & Jiang, E. Y. Biodiversity: Natural Capital of Hainan Island. Forest and Humankind. 10, 31–33 (2021).

Bannikova, A. A. et al. A new species of Neohylomys (Eulipotyphla: Galericidae) from northern Vietnam. Zootaxa 5541(3), 294–306. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5541.3.2 (2024).

Smith, A. T., Xie, Y. & Wang, S. A guide to the mammals of China (Hunan Education Press (in Chinese), 2009).

Abramov, A. V., Bannikova, A. A., Lebedev, V. S. & Rozhnov, V. V. A broadly distributed species instead of an insular endemic? A new find of the poorly known Hainan gymnure (Mammalia, Lipotyphla). ZooKeys. 795, 77–81. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.795.28218 (2018).

Shou, Z. H. & Wang, S. One new genus and one new species of the insectivorous mammal family (Insectivora) from Hainan—Neohylomys hainanensis. Acta Zoologica Sinica. (03), 422–425+429 (1959).

Johnston, C. & Smith, A. T. Neohylomys hainanensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: e. T10588A22326961. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T10588A22326961 (2016)

Jiang, Z. G., Zhou, K. Y. & He, K. Diversity of China’s Mammals Inventory (Straits Publishing Distribution Group (in Chinese), 2024).

Li, Y., Wu, Y., Lin, L. K., Harada, M. & Motokawa, M. First karyological and molecular study of the Hainan gymnure Neohylomys hainanensis (Erinaceomorpha: Erinaceidae). Mammalia 72(4), 344–346. https://doi.org/10.1515/MAMM.2008.037 (2008).

Burkart, E. & Jiang, X. L. Odontological and carniologiccal comparison of the recent hedgehog Neotetracus with Hylomys and Neohylomys (Erinaceidae, Insectivora, Mammalia). Vertebrata Palasiatica. 49(4), 406–422. https://doi.org/10.19615/j.cnki.1000-3118.2011.04.004 (2011).

He, K. et al. An estimation of Erinaceidae phylogeny: A combined analysis approach. PLoS ONE 7(6), e39304. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039304 (2012).

Tu, F. Y., Hou, X. D., Lu, Q. J. & Zhai, X. F. The complete mitochondrial genome Hainan Gymnure Neohylomys hainanensis. F1000Research. 12(249), 294. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.131600.1 (2023).

Zeng, Y. et al. Museum specimens shedding light on the evolutionary history and cryptic diversity of the hedgehog family Erinaceidae. Integr. Zool. https://doi.org/10.1111/1749-4877.12909 (2024).

Guisan, A. & Thuiller, W. Predicting species distribution: Offering more than simple habitat models. Ecol. Lett. 8(9), 993–1009. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00792.x (2005).

Qiao, H. J., Hu, J. H. & Huang, J. H. Theoretical basis, future directions, and challenges for ecological niche models. Sci. entia. Sinica. Vitae. 43, 915–927. https://doi.org/10.1360/052013-192 (2013).

Zhu, G. P., Liu, G. Q., Bu, W. J. & Gao, Y. B. Ecological niche modeling and its applications in Biodiversity conservation. Biodiver. Sci. 21(1), 90–98. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1003.2013.09106 (2013).

Lehmann, A., Leathwick, J. R. & Overton, J. M. Assessing new zealand fern diversity from spatial predictions of species assemblages. Biodivers. Conserv. 11, 2217–2238. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021398729516 (2002).

Phillips, S. J. & Dudík, M. Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: New extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 31(2), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0906-7590.2008.5203.x (2008).

Matyukhina, D. S. et al. Assessing the influence of environmental parameters on Amur tiger distribution in the Russian far east using a MaxEnt modeling approach. Achievements in the Life Sciences. 8(2), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.als.2015.01.002 (2014).

Ab Lah, N. Z., Yusop, Z., Hashim, M., Salim, J. M. & Numata, S. Predicting the habitat suitability of Melaleuca cajuputi based on the MaxEnt species distribution model. Forests 12(11), 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12111449 (2021).

Mu, C. S. & Li, P. B. Assessing the invasion risk of Chelydra serpentina in China under current and future climate change scenarios. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11, 1277058. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2023.1277058 (2023).

Wilson, D. E., Reeder, D. & Sautter, G. Order Erinaceomorpha. Plazi.org taxonomic treatments database. Checklist dataset. https://doi.org/10.15468/c5rvdc accessed via GBIF. org on 2024-12-17. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/4867335332 (2005)

Aiello-Lammens, M. E., Boria, R. A., Radosavljevic, A., Vilela, B. & Anderson, R. P. spThin: An R package for spatial thinning of species occurrence records for use in ecological niche models. Ecography 38(5), 541–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.01132 (2015).

Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G. & Arvis, A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25(15), 1965–1978. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1276 (2005).

Lobo, J. M., Jiménez-Vaverde, A. & Hortal, J. The uncertain nature of absences and their importance in species distribution modelling. Ecography 33(1), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.06039 (2010).

Ashoori, A. et al. Habitat modeling of the common pheasant Phasianus colchicus (Galliformes: Phasianidae) in a highly modified landscape: Application of species distribution models in the study of a poorly documented bird in Iran. Eup. zool. J. 85, 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750263.2018.1510994 (2018).

Huang, R. et al. Predicting the distribution of suitable habitat of the poisonous weed Astragalus variabilis in China under current and future climate conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 921310. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.921310 (2022).

Chen, G. Z., Li, X. & Liu, X. P. Global land projection based on plant functional types with a 1-km resolution under socio-climatic scenarios. Sci. Data. 9, 125. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01208-6 (2022).

Bosso, L. et al. Nature protection areas of Europe are insufficient to preserve the threatened beetle Rosalia alpine (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae): Evidence from species distribution models and conservation gap analysis. Ecol. Entomol. 43, 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12485 (2018).

Steele, K. & Werndl, C. Climate models, calibration, and confirmation. Br. J. Philos. Sci. 64, 609–635. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjps/axs036 (2013).

Cobos, M. E., Peterson, A. T., Barve, N. & Osorio-Olvera, L. kuenm: An R package for detailed development of ecological niche models using Maxent. Peer J. 7, e6281. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6281 (2019).

Peterson, A. T., Papes, M. & Soberon, J. Rethinking receiver operating characteristic analysis applications in ecological niche modeling. Ecol. Model. 213, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2007.11.008 (2008).

Anderson, R. P., Lew, D. & Peterson, A. T. Evaluating predictive models of species’ distributions: Criteria for selecting optimal models. Ecol. Model. 162, 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3800(02)00349-6 (2003).

Warren, D. L. & Seifert, S. N. Ecological niche modeling in Maxent: The importance of model complexity and the performance of model selection criteria. Ecol. Appl. 21(2), 335–342. https://doi.org/10.1890/10-1171.1 (2011).

Elith, J. et al. A statistical explanation of MaxEnt for ecologists: Statistical explanation of MaxEnt. Divers. Distrib. 17(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2010.00725.x (2011).

Allouche, O., Tsoar, A. & Kadmon, R. Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: Prevalence, Kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). J. App. Ecol. 43, 1223–1232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01214.x (2006).

Swets, J. A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 240(4857), 1285–1293. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3287615 (1988).

Shi, X. et al. Prediction of the potentially suitable areas of Litsea cubeba in China based on future climate change using the optimized MaxEnt model. Ecol. Indic. 148, 110093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110093 (2023).

Monserud, R. A. & Leemans, R. Comparing global vegetation maps with the Kappa statistic. Ecol. Model. 62, 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3800(92)90003-W (1992).

Luo, M., Wang, H. & Lyu, Z. Evaluating the performance of species distribution models Biomod2 and MaxEnt using the giant panda distribution data. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 28(12), 4001–4006. https://doi.org/10.13287/j.1001-9332.201712.0115 (2017).

Han, H. et al. Assessing the potential suitability of forest stands as Kirengeshoma koreana habitat using MaxEnt. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 10(2), 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11355-013-0246-3 (2013).

Anadón, J. D. et al. Individualistic response to past climate changes: niche differentiation pro motes diverging quaternary range dynamics in the subspecies of Testudo graeca. Ecography 38, 956–966. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.01163 (2015).

Abolmaali, S. M. R., Tarkesh, M. & Bashari, H. MaxEnt modeling for predicting suitable habitats and identifying the effects of climate change on a threatened species, Daphne mucronata, in central Iran. Ecol. Inform. 43, 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2017.10.002 (2018).

Liu, B. et al. The potential distribution and dynamics of important vectors Culex pipiens pallens and Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus in China under climate change scenarios: An ecological niche modelling approach. Pest. Manag. Sci. 76(9), 3096–3107. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.5861 (2020).

Deng, C. et al. Potential suitable habitats of chili pepper in China under climate change. Plants. 13, 1027. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13071027 (2024).

Capinha, C., Larson, E. R., Tricarico, E., Olden, J. D. & Gherardi, F. Effects of climate change, invasive species and disease on the distribution of native European crayfishes: Global change and European crayfishes. Conserv. Biol. 27, 731–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12043 (2013).

Brown, J. L., Bennett, J. R. & French, C. M. SDMtoolbox 2.0: the next generation Python–based GIS toolkit for landscape genetic, Biogeographic and species distribution model analyses. Peer J. 5, e4095. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4095 (2017).

Matukhina, D. S. et al. Assessing the influence of environmental parameters on Amur tiger distribution in the Russian far east using a MaxEnt modeling approach. Achievem. Life Sci. 8(2), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.als.2015.01.002 (2014).

Zhao, X. J. et al. Impact of sample size and spatial distribution on species distribution model. J. Lanzhou Univ. 54 (2), 208–215. https://doi.org/10.13885/j.issn.0455-2059.2018.02.010 (2018).

Liu, T., Cao, J. H., Qi, R., Li, B. & Gao, B. Q. Research of potential geographical distribution of Picea purpures based on GIS and MaxEnt under different climate conditions. Acta Bot. Boreal. Occident. Sin. 42(03), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.7606/j.issn.1000-4025.2022.03.0481 (2022).

Gan, R. X. et al. Analysis of the potential distribution of Meriones meridianus in China under climate change. Acta Agrestia Singica. 30(12), 3372–3380 (2022).

Patiño, J. et al. Spatial resolution impacts projected plant responses to climate change on topographically complex islands. Divers. Distrib. 29, 1245–1262. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13757 (2023).

Xu, L. H., Liu, Z. H. & Yu, S. M. Birds and Beasts in Hainan Island (Science Press (in Chinese), 1983).

Wu, Y., Jiang, H. S., Peng, H. Y., Li, S. L. & Wang, W. Y. Preliminary study on the species diversity of mammals in the Diaoluoshan nature reserve. Journal of Guangzhou University (Natural Science Edition). 2(06), 505–511. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-4229.2003.06.003 (2003).

Jiang, H. S. et al. Biodiversity and Conservation of Hainan Yinggeling Nature Reserve (China Forestry Publishing House (in Chinese), 2013).

Paise, G. & Vieira, E. M. Daily activity of a neotropical rodent (Oxymycterus nasutus): Seasonal changes and influence of environmental factors. J. Mammal. 87 (4), 733–739. https://doi.org/10.1644/05-MAMM-A-158R5.1 (2006).

Vieira, E. M., Baumgarten, L. C., Paise, G. & Becker, R. G. Seasonal patterns and influence of temperature on the daily activity of the diurnal neotropical rodent Necromys lasiurus. Can. J. Zool. 88(3), 259–265. https://doi.org/10.1139/z09-142 (2010).

Kim, S., Park, H., Park, I., Han, T. & Kim, H. G. Effect of temperature on the development of Alphitobius diaperinus (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Int. J. Indust. Entomol. 35(2), 106–110. https://doi.org/10.7852/ijie.2017.35.2.106 (2017).

Dodge, C. & Stouthamer, R. Effect of temperature on fecundity, development, and emergence of the invasive ambrosia beetle Euwallacea kuroshio (Coleoptera: Scolytinae). Agr. Forest. Entomol. 23(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/afe.12407 (2020).

Tan, H. J., Cai, R. S., Du, J. G. & Hu, W. J. Climate change and marine ecosystems: Impacts adaptation and vulnerability—Interpretation of the IPCC AR6 WGⅡ Report. Trans Atmos. Sci. 45(4), 489–501. https://doi.org/10.13878/j.cnki.dqkxxb.20220411001 (2022).

Jackson, M. M., Gergel, S. E. & Martin, K. Effects of climate change on habitat availability and configuration for an endemic coastal alpine bird. PLoS ONE 10(11), e0142110. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142110 (2015).

Kougioumoutzis, K. et al. Impacts of climate and land use change on endemic plant distributions in a Mediterranean Island Hotspot: The Case of Evvia (Aegean, Greece). Climate. 13, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13050100 (2025).

Zhang, C. H. et al. The influence of the mountainous terrain in the central part of Hainan Island on the weather and climate. Adv. Meteorol. Technol. 10(04), 70–73 (2020).

Wu, S. A., Xing, C. A. & Zhu, J. J. Analysis of climate characteristics of Hainan Island. J. Trop. Biol. 13(4), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.15886/j.cnki.rdswxb.2022.04.001 (2022).

Parmesan, C. & Yohe, G. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 421, 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01286 (2003).

Bertrand, R. et al. Changes in plant community composition lag behind climate warming in lowland forests. Nature 479, 517–520. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10548 (2011).

McCain, C. M. & Colwell, R. K. Assessing the threat to montane biodiversity from discordant shifts in temperature and precipitation in a changing climate. Ecol. Lett. 14(12), 1236–1245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01695.x (2011).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Jichao Wang for providing the research platform. This study was supported by the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 323MS037 and 321RC544).

Funding

This study was supported by the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 323MS037 and 321RC544).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: F.T.; methodology: Y.Q., C.M.; formal analysis: Y.Q., C.M.; data collection: Y.Q., Y.Y., F.T.; writing—original draft preparation: Y.Q., C.M., F.Y.; writing—review and editing: Y.Q., C.M., F.Y.; supervision: F.T. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yaqin Qiao and Chaosheng Mu are co–first authors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiao, Y., Mu, C., Yang, Y. et al. Effects of climate change on the habitat suitability of the endangered Hainan gymnure (Neohylomys hainanensis) on Hainan Island. Sci Rep 15, 41092 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24884-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24884-x