Abstract

Human beings regularly adjust behaviors across social contexts as part of impression management (IM). Recently, “camouflaging” has been described as the behavioral strategies autistic individuals employ to blend into neurotypical social norms, often at costs to psychological wellbeing. It remains unclear whether camouflaging is unique to autism or overlaps with established IM constructs in terms of shared latent facets, socio-motivational and cognitive drivers, and mental health outcomes. To address this knowledge gap, we surveyed a representative US general population sample of 972 adults, utilizing self-report measures to assess camouflaging/IM, along with their theoretical socio-motivational and cognitive antecedents and mental health consequences. We first applied joint exploratory factor analysis to identify the latent facets underlying measures across camouflaging and existing IM constructs. Two latent IM facets emerged: “intentional use” (purposeful IM use) and “self-efficacy” (self-perceived IM capacity). Structural equation modeling suggested that greater IM intentional use was driven by socio-motivational pressures and predicted poorer mental health, whereas stronger IM self-efficacy was supported by executive functioning and perspective-taking and linked to better mental health. Neurodivergent traits exhibited unique moderation effects; in those with elevated autistic traits, greater IM intentional use and self-efficacy were both linked to poorer mental health. Yet, in those with elevated ADHD traits, greater IM self-efficacy was linked to better mental health. Critically, greater IM self-efficacy may buffer the negative impacts of IM intentional use on mental health. Our findings reveal an expanded understanding of camouflaging as part of multi-faceted IM, which exhibits complex relationships with mental health, moderated by neurodivergence. The implications point to conceptual and methodological advances for social coping research across neurodiverse groups, especially for developing tailored support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human beings adjust behaviors to project different impressions across social situations. This practice of impression management (IM) serves to secure resources, find employment, build friendships, and, for some, to survive in a hostile social world1,2. The drivers, strategies, and outcomes of IM are modulated by dynamic transactions between individuals and their social environments3. Recently, the concept of “camouflaging” has been associated with IM experiences. Camouflaging describes the conscious and, potentially, non-conscious strategies that some autistic people employ to portray outwardly neurotypical appearances in social interactions. These include strategies that suppress autistic presentations (e.g., inhibiting stimming) or adopt behaviors aligned with social norms (e.g., memorizing conversation scripts)4,5,6. Camouflaging has gained significant attention in autism research lately4,7,8.

We have proposed the transactional IM framework to reconceptualize camouflaging as an aspect of broader IM experiences across human groups3. This framework seeks to unify established IM-related constructs2,9,10,11 with the various concepts being studied in autistic camouflaging research (e.g., “masking”, “passing”, “compensation”, “adaptive morphing”)4,6,12,13, all within a shared theoretical foundation. Importantly, it emphasizes that distinctive IM features can arise from the transactions between individuals and their social contexts. For example, for autistic people or individuals high in autistic traits, camouflaging/IM experiences reflect the interplay between autism-related cognitive characteristics and the social challenges navigating neurotypical settings3. This framework enables researchers to extract shared knowledge across neurodevelopmental and IM research to empirically pinpoint the mechanisms linking camouflaging/IM with social motivations, cognitive capacities, and mental health. Concurrently, the framework enhances the analytic precision to examine if these links vary by individual differences such as neurodivergence (e.g., autistic and ADHD traits).

What does “camouflaging” mean?

Operationalizations of camouflaging vary4,13,14, with definitions focusing on describing self-reported strategy use, the frequency or intentions behind these behaviors, or phenomenological characteristics7,8,15. Most camouflaging research to date relies on the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q)5,15, yet its self-report nature only captures one’s subjectively recalled extent of intentional camouflaging use, rather than actual efforts, efficacy, or outcomes involved16. It is essential to distinguish among these facets because they may differently associate with socio-motivational, cognitive, and mental health factors17,18. Although research utilizing the CAT-Q has linked intentional camouflaging use with adverse mental health, these associations may differ if researchers assess, for instance, individuals’ objective efficacy or subjective confidence in their ability to camouflage. However, there are currently very limited measures available that tap into these alternative facets. Observational and reflective methods seek to quantify one’s camouflaging tendencies but not how “successful” they are5,19,20. The discrepancy-based approach contrasting how observable one’s autistic behavioral appearance is (e.g., as measured by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule) with their self-perceived characteristics (e.g., as measured by self-reported autistic traits) or cognitive features (e.g., mentalizing), only infers camouflaging abilities indirectly15. Therefore, despite various existing tools, the complexity of autistic camouflaging is yet to be fully captured.

Considerable debate persists over conceptualizations of camouflaging16,21,22. Some researchers contend that IM serves only as an analogy to camouflaging23, while others posit that camouflaging should be construed as a subset of ubiquitous IM experiences3,5,19,24,25. One critical way to tackle this debate is to assess camouflaging tendencies in the general population alongside other established IM-related constructs. Our recent analyses from a representative US general population sample showed that neurotypical individuals camouflage too17, as measured by the CAT-Q5,15. The CAT-Q showed nearly identical dimensional structure in the general population compared with findings from autism-enriched samples5,15,17, indicating significant continuity in experiences of camouflaging. In the same sample, CAT-Q scores were strongly associated with Self-Presentation Tactics (SPT) scale scores17, which measure one’s proclivity to engage in specific types of tactics that control one’s public image9. This finding provides initial evidence for conceptual convergence between camouflaging and known IM constructs. Moreover, recent findings show that Japanese autistic adults tend to engage in greater camouflaging with other autistic people than with neurotypical individuals26. Although various interpretations and cultural nuances may be involved, these findings imply that camouflaging could be understood as a general social coping strategy for managing impressions and fostering relationships, rather than an autism-exclusive phenomenon solely to cope with neurotypical social demands27.

Under the transactional IM framework, latent IM facets can potentially be distinguished across IM-related measures. Despite fragmented terminologies, operationalizations of camouflaging and concepts described in past IM research largely overlap. Echoing Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical analysis of IM, the “frontstage” encapsulates actively generated approaches such as deliberate self-presentation tactics and compensation strategies of camouflaging (e.g., generating and memorizing conversation scripts) that explicitly project a favorable image. The “backstage” encompasses socially discredited or discreditable information that is suppressed through defensive approaches such as self-concealment and masking strategies of camouflaging (e.g., inhibiting stimming tendencies)1,3. Meanwhile, as opposed to measuring specific strategies, the IM concept of self-monitoring captures individuals’ sensitivity to particular social situational demands and their capacity to monitor and regulate their own social behaviors accordingly11. Hence, self-monitoring may tap into one’s ability to execute IM.

The psychometric relations between IM (e.g., self-presentation tactics, self-concealment, self-monitoring)2,9,10,28 and camouflaging constructs (e.g., masking, compensation)4,13,15 as well as their plausibly joint latent facets remain unclear. These facets likely have different drivers and relevance for wellbeing across individuals. “Transactional” IM entails that facets such as intention, ability, effort, and efficacy may manifest uniquely depending on the interaction between individual traits (e.g., neurodivergent features) and contextual pressures (e.g., normative social influences). For example, autistic individuals and those with elevated autistic traits may find camouflaging more difficult due to cognitive differences in areas such as social cue reading29. These struggles are compounded by transactions with social contexts, including the stigma, social rejection, and pervasive misfit experienced by many autistic people in neurotypical spaces, which can aggravate the mental health risks associated with camouflaging/IM3. Additionally, the intention behind camouflaging/IM use can vary across social groups. Marginalized individuals (e.g., ethnic, sexual, and gender minorities) may be more compelled to adopt defensive IM to conceal stigmatized traits and reduce discrimination, while dominant social majority groups may employ IM proactively to achieve social advantages2,3,30,31,32. In the following sections, we outline how IM facets relate to cognitive, socio-motivational, and mental health factors, considering as well the modulating roles of neurodivergent (autistic and ADHD) traits.

Theoretical cognitive and socio-motivational antecedents of camouflaging/IM

The cognitive mechanisms of camouflaging are not yet clear33. The transactional IM framework proposes candidate mechanisms based on the IM literature3. During social interactions, individuals track dynamic changes in their social space, inhibit socially unfavorable behaviors, and generate favorable ones, all in concert. These processes likely rely on executive functions such as inhibition, planning, working memory, and attention shifting, which are critical for the complex IM decisions involved3. Additionally, successful camouflaging requires decoding evolving social expectations as interactions unfold34. Hence, perspective-taking is likely foundational to supporting social inference to decode and enact the appropriate social script.

Research so far suggests that stronger executive functioning is associated with increased camouflaging in autistic people and IM in the general population33,35,36. The role of perspective-taking is less conclusive37, but initial neuroimaging evidence links together brain areas supporting social inference and perspective-taking with camouflaging/IM in both autistic and neurotypical people38,39,40. There are several potential reasons why a clear link between perspective-taking and autistic camouflaging has not been observed. Mechanistically, executive functioning and perspective-taking may primarily enable an individual’s camouflaging ability rather than intent or frequency. Another possibility is that autistic neurocognitive differences, compounded by the pervasive cross-neurotype socio-communicative disjuncture41,42,43,44, create substantial barriers for autistic people to attend to perspective-taking and social decoding when managing impressions in neurotypical social contexts. Hence, they may use alternative cognitive routes when deciding whether and how to camouflage, such as leveraging exemplar-based memory to reinstate previous social episodes and extract template IM behaviors45.

Camouflaging/IM is driven by relational motivations2,4, as well as other instrumental reasons such as gaining/maintaining employment or enhancing relational self-esteem4,46,47,48,49. The transactional IM framework postulates two core relational motivations: mitigating thwarted belonging and coping with social stigma3. The needs for social affiliation and approval drive individuals to monitor their social actions and facilitate favorable appearances. Many autistic individuals also report social connections and friendships as primary goals of their camouflaging4,7,8,50. Although both neurotypical and autistic people manage impressions and camouflage for interpersonal needs, autistic individuals are particularly susceptible to negative perceptions during initial encounters51,52,53, as well as rejection and loneliness54,55. This lower social favorability baseline means that autistic individuals may be compelled to camouflage more extensively to reduce their social distance with others3,31.

A significant barrier to social affiliation is stigma56,57. Minoritized groups, including autistic people, may use camouflaging/IM to avoid stigmatization4,7,8, reassert devalued identities7, or mitigate threats such as physical harm, discrimination, and trauma58,59,60. One particularly potent form of stigma is internalized stigma18,61, whereby discrediting beliefs about oneself become so ingrained that the individual engages in camouflaging/IM not only to present a social front but also as a self-preservation strategy to ease deep-seated self-disapproval. Many autistic people report autism as being integral to who they are62, but they are urged to camouflage due to strongly felt sense of inferiority and poor self-image after having subscribed to neurotypical social standards25. Compared to perceived or experienced stigma, camouflaging/IM driven by internalized stigma can have more dire consequences for mental health18.

Thwarted belonging and internalized stigma may motivate camouflaging/IM directly or indirectly through social anxiety. Social anxiety may be a key driver of camouflaging/IM as a protective response to perceived social-evaluative threat25,63,64. Strong belonging needs and self-devalued identity can both heighten social anxiety, which in turn prompts camouflaging/IM as a coping mechanism. Consistent with this account, researchers have identified fear of negative evaluation (i.e., a key aspect of social anxiety) to be an important predictor of increased camouflaging as well as a mediator of the positive link between perceived stigma and camouflaging in autistic adults65. In the general population, social anxiety also partially explains the association between greater internalized stigma and greater camouflaging use18. Nevertheless, it remains unknown whether alternative facets of camouflaging/IM follow the same mediative pathways.

The general population is driven by similar social motivations to camouflage and engage in self-presentation as autistic people, including greater social belonging needs, internalized stigma, social anxiety, and public self-consciousness17. However, the transactional IM framework posits that the degree of these social pressures may differ for autistic individuals, as well as the extent of their strategy use and associated cognitive load3. Notably, camouflaging and self-presentation tactics also jointly mediate the relationships between internalized stigma and poor mental health in the general population18. This suggests that although camouflaging/IM is a social coping response, it may fail to alleviate and even exacerbate the mental health burdens that stem from internalized stigma. It is crucial to understand whether this pattern is specific to the intentional use of camouflaging/IM or extends to other facets.

Theoretical mental health consequences of camouflaging/IM

Across the general population, camouflaging and self-presentation are associated with similar mental health experiences, including increased anxiety and depression symptoms, self-regulatory fatigue and inauthenticity18. However, it is unclear if other IM constructs such as compensation13, self-concealment10, or self-monitoring11, or different camouflaging/IM facets, would show converging or diverging mental health associations. Notably, camouflaging/IM is not an inherently negative aspect of human social experience3. It can be constructive for fostering personal wellbeing and social adjustment66,67. Yet, when camouflaging/IM interacts with specific individual traits or contextual pressures, the outcomes can become hazardous68. For example, false self-presentation and the concealment of stigmatized traits in marginalized communities, such as sexually diverse individuals and people with mental illnesses, have been linked to depression, anxiety, suicidality, stress, and identity issues69,70,71,72. Gender identity can also modulate camouflaging/IM effects on mental health, such that women face greater psychological repercussions than men18. The mental health implications of camouflaging/IM in different neurodivergent groups are also gaining traction27,73,74.

The resource-intensive nature of IM imposes a significant cognitive burden, especially on those who must sustain these behaviors for extended periods, lack alternative coping options, or face cognitive challenges75,76. For instance, the additional need to suppress stigmatized autistic behaviors (e.g., literal communication, repetitive movements) and the cognitive burden during camouflaging/IM induced by autism-related cognitive differences (e.g., in social decoding) may both exacerbate the mental health toll. Autistic individuals report heightened distress, anxiety, depression, inauthenticity, and burnout linked to camouflaging4,7,8. These negative outcomes may reflect a greater toll compared with the IM practiced by neurotypical people3,23. Correspondingly, people in the general population with higher compared to lower autistic traits report worse mental health at increased camouflaging levels18. Cognitive ADHD traits (e.g., inattention, impulsivity) may also exacerbate the psychological costs of IM in similar cirumstances77,78. Yet, unexpectedly, individuals with higher compared to lower self-reported ADHD traits exhibit better mental health at increased camouflaging levels18. This divergence underscores the need to tease apart how aspects of neurodivergent features and socio-contextual demands moderate the ways in which different camouflaging/IM facets impact mental health across different individuals.

The current study

As the first empirical investigation examining camouflaging alongside IM and thoroughly testing predictions from the transactional IM framework3, this study confers important updates to our understanding of the facets in how humans present themselves, the links with socio-motivational, cognitive, and mental health factors, and the unique implications of neurodivergence. We had two objectives. First, we examined how camouflaging, as measured by the CAT-Q, relates to other IM constructs including self-presentation, self-concealment, self-monitoring, and compensation. Using joint exploratory factor analysis (EFA), we identified latent facets of IM by examining the shared factor structure across measures. Second, we examined the relationships between these IM facets and their theoretical cognitive (executive functioning, perspective-taking) and socio-motivational (internalized stigma, social belonging needs, social anxiety) antecedents, as well as their theoretical mental health consequences (depression, generalized anxiety, fatigue, subjective inauthenticity) using structural equation modeling (SEM). We then tested moderations of these relationships by autistic and ADHD traits as well as the interactions between IM facets.

Results

The final sample included 972 adults aged 18 years and older from a representative US general population sample. Participants were capable of self-reporting and providing informed consent. Data were collected via the Qualtrics platform, where participants completed a demographic questionnaire (Table 1) and self-report measures (see Methods). Participants completed five self-report measures on camouflaging and IM, including the CAT-Q5 and the Compensation Checklist (COMP)19 measuring camouflaging, the Self-Presentation Tactics (SPT)9 scale measuring self-presentation, the Self-Concealment Scale (SCS)10 measuring self-concealment, and the revised Self-Monitoring Scale (SMS)11 measuring self-monitoring. Autistic traits were measured by the Subthreshold Autism Trait Questionnaire (SATQ)79 and ADHD traits measured by the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale Part A (ASRS-A)80.

Socio-motivational measures assessed social anxiety by the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS)81, social belonging needs by the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire Thwarted Belongingness subscale (INQ-TB)82, and internalized stigma based on self-identified minority identities or social atypicalities by the adapted Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Inventory 10-item version (ISMI-10)61. Self-reported cognitive features included executive functioning as measured by the Amsterdam Executive Functions Inventory (AEFI)83, behavioral inhibition as measured by the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Brief Version (BIS-BRIEF)84, and perspective-taking as measured by the Interpersonal Reactivity Index Perspective-Taking subscale (IRI-PT)85. For mental health, generalized anxiety symptoms were assessed by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7)86, depressive symptoms were assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)87, cognitive exhaustion was assessed by the Self-Regulatory Fatigue Scale Short Form (SRF-S)88, and subjective authenticity was assessed by the Kernis-Goldman Authenticity Inventory Short Form (KGAI-SF)89 and the Self-Concept Clarity (SCC) scale90. All analyses were performed in R version 4.2.191.

IM as a multi-faceted construct

We first derived the associations among the total scale scores of the five camouflaging/IM measures and their correlations with socio-motivational, cognitive, and mental health variables. A Pearson correlation matrix (Fig. 1) revealed that the camouflaging/IM measures were moderately to strongly positively intercorrelated, except for self-monitoring. Further, compared to other camouflaging/IM measures, self-monitoring consistently exhibited opposite association patterns with non-camouflaging/IM variables. Whereas other camouflaging/IM measures were negatively associated with cognitive variables such as executive functioning, inhibition, and perspective-taking, self-monitoring showed positive associations with these cognitive variables. Similarly, whereas other IM measures correlated positively with social belonging needs, internalized stigma, and social anxiety, self-monitoring showed negative or no associations with these socio-motivational variables. Lastly, whereas other IM measures correlated with poorer mental health, self-monitoring showed weak to negligible associations with mental health. These distinct correlation profiles suggest that self-monitoring may represent a unique IM facet.

Correlation matrix of the total scale scores of all variables. Warm color represents positive associations, and cold color represents negative associations. The color gradient represents the strength of the association. Only significant (i.e., p < 0.05 after Benjamini-Hochberg corrections for multiple comparisons) correlations have been depicted. Amsterdam Executive Function Inventory (AEFI); Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Brief Version (BIS-BRIEF); Interpersonal Reactivity Index Perspective-Taking subscale (IRI-PT); Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness scale (ISMI-10); Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire Thwarted Belongingness subscale (INQ-TB); Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS); Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q); Self-Presentation Tactics scale (SPT); Compensation Checklist (COMP); Self-Concealment Scale (SCS); Revised Self-Monitoring Scale (SMS); Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7); Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9); Kernis-Goldman Authenticity Inventory Short Form (KGAI-SF); Self-Concept Clarity scale (SCC); Self-Regulatory Fatigue scale Short Form (SRF-S); Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale Part A (ASRS-A); Subthreshold Autism Trait Questionnaire (SATQ).

We conducted a joint EFA on a randomly selected 50% subsample (N = 486). In this joint EFA, we focused on examining whether different IM and camouflaging measures tap into common latent factors. We used summed scale scores per measure instead of modeling item-level functioning of individual scales. Following the Kaiser criterion (K1 rule), the scree plot indicated that a two-factor solution is optimal. Moreover, the two-factor model corroborated our correlation analyses. Camouflaging, compensation, self-presentation, and self-concealment scores loaded strongly onto one latent factor, while self-monitoring scores loaded by itself onto a second latent factor. The correlation between the two latent factors was negligible, r = 0.15, p < 0.001. Upon reviewing the scale items, we interpreted this distinction between the two latent factors as one of intentional use versus self-efficacy. Most IM and camouflaging scale items predominantly assessed the subjective intentional use of various IM behaviors—essentially, the degree to which participants agree or disagree with enacting specific social behaviors during interactions. Examples include “In social situations, I feel like I’m ‘performing’ rather than being myself” (item 7, CAT-Q) or “I have negative thoughts about myself that I never share with anyone” (item 10, SCS). In contrast, the SMS items were phrased to probe participants’ self-perceived ability when consciously engaging in IM behaviors. These items focused on subjective capability and self-efficacy, with wording such as “I can,” “I am able to,” and “I have the ability to.” Examples include “I can usually tell when I’ve said something inappropriate by reading it in the listener’s eyes” (item 8, SMS) or “In social situations, I have the ability to alter my behavior if I feel that something else is called for” (item 1, SMS).

Empirically validating the transactional IM framework

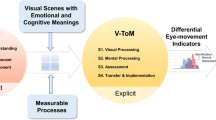

Using the full sample (N = 972), we then used SEM to examine the relations among IM, represented by the intentional use and self-efficacy facets, and the socio-motivational, cognitive, and mental health variables outlined in the transactional IM framework³. For structural paths, executive functioning, perspective-taking, social belonging needs, internalized stigma, and social anxiety were specified as cognitive and socio-motivational latent predictors of IM intentional use and self-efficacy. IM intentional use, IM self-efficacy, social belonging needs, and internalized stigma were further specified as latent predictors of mental health outcomes, which included affective symptoms (reflected by generalized anxiety and depression), fatigue, and authenticity. A full list of the indicator variables reflecting these latent variables is provided in Table 2, and all estimated structural and covariance paths are detailed in Table 3; Fig. 2. After confirming the fit of the final SEM, we additionally tested the moderation effects of autistic and ADHD traits, as well as the interaction effects between IM intentional use and self-efficacy on mental health.

Diagram of the structural model and all structural and covariance paths among the latent variables. The indicator variables are not depicted for clearer visualization. One-headed arrows are unidirectional paths that represent theoretical effects and double-headed arrows represent covariance paths. Black arrows represent significant positive relations, and red arrows represent significant negative relations. Gray dotted arrows represent non-significant paths. Residual error (E); executive functioning (EF); perspective-taking (PersTaking); impression management (IM); social belonging needs (SocNeed); social anxiety (SocAnx); internalized stigma (Stigma); self-regulatory fatigue (Fatigue); affective symptoms (Affect); felt authenticity (Authen).

In the full SEM, all indicator variables loaded substantially onto their respective latent constructs (Table 2). The model fit indices indicated an acceptable fit (robust root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.052 [0.050, 0.054], standardized root mean square residual [SRMR] = 0.066, robust comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.901). Among the significant structural paths (Fig. 2), greater IM intentional use was predicted by lower executive functioning, greater perspective-taking, higher social anxiety, greater internalized stigma, and greater social belonging needs. In contrast, IM self-efficacy was positively predicted by greater executive functioning and greater perspective-taking but lower social belonging needs. For mental health, greater IM intentional use was linked to more affective symptoms, reduced authenticity, and increased fatigue. Conversely, greater IM self-efficacy was associated with fewer affective symptoms, increased authenticity, and reduced fatigue.

Indirect effects yielded additional insights into these relationships. Social anxiety mediated the relationships between internalized stigma and IM intentional use (β = 0.110, [95% CI 0.070, 0.151]), as well as between social belonging needs and IM intentional use (β = 0.110, [95% CI 0.067, 0.154]). Furthermore, IM intentional use emerged as a key mediator of multiple pathways; specifically, it mediated the effects of internalized stigma on poorer mental health, including increased affective symptoms (β = 0.388, [95% CI 0.196, 0.581]), lower authenticity (β = -0.463, [95% CI -0.651, -0.276]), and greater fatigue (β = 0.455, [95% CI 0.216, 0.694]). Similarly, IM intentional use also mediated the links between social belonging needs and poorer mental health, including increased affective symptoms (β = 0.226, [95% CI 0.077, 0.375]) and lower authenticity (β = -0.269, [95% CI -0.434, -0.104]).

To explore latent interactions (detailed results available in the Supplemental Materials), we tested three different latent moderated SEMs with identical baseline specifications as the final SEM but included additional latent interaction paths. These three latent moderated SEMs separately examined (1) interactions between autistic traits and all latent predictors (socio-motivational, cognitive, and IM latent facets); (2) the interactions between ADHD traits and all latent predictors; and (3) the interactions between IM intentional use and self-efficacy in predicting mental health. For main effects, greater autistic and ADHD traits independently predicted greater IM intentional use (β = 0.171, p < 0.001 and β = 0.401, p < 0.001, respectively), but greater autistic traits uniquely predicted lower IM self-efficacy (β = -0.885, p < 0.001). Regarding latent interactions, as autistic trait levels increased, greater social anxiety predicted lower IM intentional use (β = -0.120, p = 0.012). Moreover, as autistic trait levels increased, greater IM intentional use predicted increased affective symptoms (β = 0.149, p = 0.013), and greater IM self-efficacy predicted lower authenticity (β = -0.132, p = 0.039). In contrast, as ADHD trait levels increased, greater IM self-efficacy predicted decreased affective symptoms (β = -0.077, p = 0.041). Lastly, among individuals with greater IM self-efficacy, the positive link between IM intentional use and affective symptoms became weaker (β = -0.064, p = 0.016).

Discussion

This study aimed to identify the latent facets underlying IM and camouflaging in the general population, and examine how these IM facets relate to socio-motivational, cognitive, and mental health factors hypothesized in the transactional IM framework3. Camouflaging overlaps conceptually and empirically with established IM constructs, but this overarching IM itself has two distinct facets: intentional use and self-efficacy. IM intentional use was associated with greater social pressures and perspective-taking skills but negatively associated with executive functioning. In contrast, IM self-efficacy was not linked to social pressures but might be enabled by greater perspective-taking and executive functioning. Greater IM intentional use was linked to poorer mental health, whereas greater IM self-efficacy corresponded with better mental health. Additionally, IM intentional use mediated the links from internalized stigma and social belonging needs to adverse mental health. Importantly, IM demonstrated neurodivergence-dependent patterns. Both IM intentional use and self-efficacy were associated with poorer mental health for those with elevated autistic traits, yet IM self-efficacy was associated with more positive mental health for those with elevated ADHD traits. Finally, for those with higher IM intentional use, having greater IM self-efficacy might be protective against associated mental health strains.

“Intentional use” and “self-efficacy” as separable IM facets

The construct of camouflaging, as measured by CAT-Q items derived from autistic people’s lived experiences8,92,93, converges with the general population’s intention to engage in IM. This novel finding highlights a shared, intrinsic human drive, including among autistic people, to manage impressions for social coping. However, intentional use of IM strategies appears distinct from one’s subjective ability to implement them. Variations in IM intentional use and self-efficacy may explain the diverse motivations and capacities observed in autistic camouflaging research22, as well as in broader human societal contexts across different groups (e.g., marginalized communities)10,94 and settings (e.g., social media, online dating, workplaces)37,95. For example, individuals with moderate IM intentional use but high self-efficacy may view IM as an ordinary practice to gain social capital or enhance status2. Conversely, marginalized groups may adopt IM primarily as a self-preservation mechanism, driven by heightened and compelled use of IM56. Autistic individuals with similarly intensified IM intentional use may strive to manage impressions but face challenges due to cognitive differences, adding an extra layer of burden18. Still others, with low IM intentional use and self-efficacy, may forego IM altogether despite social repercussions. Knowledge of how intentional use and self-efficacy interact to mold the IM landscape is critical for facilitating context-situated IM that optimizes self-esteem, social adaptation and wellbeing32.

IM intentional use and self-efficacy, measured by self-report questionnaires in this study, represent two of the several possible facets of IM. A fuller profile of IM facets warrants novel measurements and empirical investigation. For instance, camouflaging has been described both as an instinctive defense mechanism and a deliberate coping decision20,31,96,97. This duality mirrors the “non-conscious” and “conscious” dimensions often attributed to general IM98. An example of this distinction is the habitual use of overlearned behavioral scripts by immigrants assimilating into new cultures99, compared to context-tailored and deliberate self-presentation tactics such as self-promotion, ingratiation, or strategic disclosure of personal achievements and failures in the workplace9,100. There may also be distinctions between “deep” (complex and flexible strategies that necessitate genuine social understanding) versus “shallow” (superficial strategies like imitation, eye contact, and nodding to get by) forms of IM19,35. The effectiveness and practicality of “deep” and “shallow” IM likely depend on one’s level of social adaptability and cognitive capacities, such as verbal versus non-verbal IM skills or perspective-taking14,23. Empirical insights into if and how IM facets present in minimally speaking individuals, those with intellectual disabilities, or other mental health conditions remain scarce101.

“The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak”: mechanistic and wellbeing implications

A key finding is that IM intentional use and self-efficacy have distinct relations with socio-motivational, cognitive, and mental health variables. Specifically, greater IM intentional use is linked to poorer mental health across affective symptoms, fatigue, and authenticity, whereas greater IM self-efficacy correlates with better mental health across the same domains. This contrast echoes with the adage, “the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.” Individuals with strong intentions to use IM strategies but find them more effortful and challenging to undertake may be more vulnerable to mental health harms. In fact, our results suggest that IM self-efficacy may buffer the adverse effects of elevated IM intentional use on affective symptoms. The distinct predictors of IM intentional use and self-efficacy further underscore this dissociation. IM intentional use is positively associated with perspective-taking. One of several possible interpretations is that individuals more attuned to others’ expectations may feel heightened public self-consciousness and social pressure to meet them. This speculation aligns with research linking perspective-taking to greater public self-consciousness102,103, and studies showing how heightened self-focus increases autistic people’s felt pressure to meet inferred social demands25,63. However, IM intentional use is also negatively associated with executive functioning, suggesting that those most motivated to manage impressions may struggle to mobilize the requisite cognitive resources. Equally, reduced executive functioning (e.g., struggling to inhibit socially undesirable behaviors) may amplify the felt need to mask these tendencies in response to social demands. By contrast, IM self-efficacy is associated with both greater perspective-taking and executive functioning. Together, these findings indicate that while the perceived need to manage impressions arises from awareness of social expectations, the self-confidence to do so effectively depends on additional cognitive capacities and is critical for mitigating mental health strains.

The association between IM intentional use and poor mental health appears to stem from socio-motivational pressures. This mediative effect parallels documented qualitative findings on lived camouflaging experiences from autistic people8. Higher levels of internalized stigma and social belonging needs contribute to greater IM intentional use, which, in turn, mediates the relationships between these social pressures and adverse mental health. This suggests that individuals from marginalized groups, such as neurodivergent individuals, may develop heightened IM use to alleviate self-discredited identities and social exclusion. Yet this coping approach comes with psychological repercussions. Such drives and psychological harms can be exacerbated in individuals experiencing multiple social minoritization104, necessitating future research to unpack the impacts of intersectional internalized stigma. Notably, internalized stigma did not directly impact mental health in this model, contrasting with previous findings from the same sample18. A possible explanation is that IM intentional use, now expanded to include the self-concealment construct, may fully mediate the link between internalized stigma and mental health. The intent to hide or suppress one’s true self may be so potent that it substantially accounts for the mental health impacts of internalized stigma.

IM self-efficacy, in contrast, is associated with better mental health. Although prior research links camouflaging/IM with poorer mental health outcomes7,8, our findings indicate that individuals who report being more skilled at IM may experience it as less psychologically taxing. Furthermore, IM self-efficacy appears unassociated with the socio-motivational drivers tested in this study but rather reliant on executive functioning and perspective-taking capacities. This implies that social pressures such as internalized stigma or belonging needs are less relevant for self-perceived IM capability. It may be the case that more practical, instrumental enablers like status-seeking, self-esteem enhancement, and material or opportunity gains may be more salient correlates of IM self-efficacy across the general population2,32,105. Alternatively, while IM intentional use may be driven by broad, pervasive social pressures, IM self-efficacy may be more responsive to specific situational demands (e.g., circumstantial pressures during job interviews) whereby individuals tailor their social performances to fit varying contexts. However, our interpretations involving IM self-efficacy should be read with caution. The extent to which these associations with the IM self-efficacy facet is due to true underlying abilities or one’s confidence in one’s IM ability cannot be disentangled given the self-report nature of this study.

Both autistic and ADHD traits are subject to social scrutiny and stigma, which may contribute to their links with heightened IM intentional use. However, neurodivergence-dependent nuances were observed. Higher levels of autistic traits, but not ADHD traits, were associated with lower IM self-efficacy. Individuals with more pronounced autistic traits may face additional IM challenges due to cognitive differences that affect social inference29 or persistent social misalignment in neurotypical environments44. In contrast, those with higher ADHD traits may not need to extensively re-learn social expectations during IM, despite other difficulties. Notably, greater autistic traits appeared to amplify the positive link between IM intentional use and affective symptoms but also contributed to a more negative link between IM self-efficacy and authenticity. This pattern likely attests to the immanent harms of pervasively “performing” a different self, even when individuals believe they are apt at doing so. Meanwhile, those with higher ADHD traits, similar to other non-autistic people in the general population, may not have to change themselves so fundamentally but instead engage in camouflaging/IM to optimize behavioral fit with specific situational demands (e.g., classroom or workplace expectations). In such scenarios, IM self-efficacy helps reduce the associated psychological load. The mechanisms for these neurodivergence-dependent distinctions are still unclear, but the findings highlight the need to consider transactionality when delineating the toll of IM on individuals3, especially among neurodivergent individuals.

Lastly, uniquely in individuals with elevated autistic traits, greater social anxiety predicted lower IM intentional use. While counterintuitive at first glance, several viable explanations exist for this moderation effect. With heightened autistic traits, it may be that social anxiety is a less salient driver of IM intentional use due to autism-related cognitive differences that differentially attune social cues, expectations, and felt uncertainty. Alternatively, the use of IM may be more of a survival mechanism for individuals who hold evidently elevated autistic traits to manage tangible threats of harm, bullying, or trauma3,31,106 rather than to mitigate felt anxiety in social situations.

Limitations and future directions

Despite multiple available methods, current measures primarily tap into subjectively recalled camouflaging/IM and do not capture the full conceptual complexity15. We show in this study how significant insights can be gained by marshalling validated self-report instruments from historical and ongoing IM research across diverse domains, including social media107, personality108, school109 and organizational settings49. Specifically, we expand the current understanding of conscious camouflaging by demonstrating its joined facets with IM and the facets’ distinct associations with socio-motivational and cognitive antecedents as well as mental health consequences. Nonetheless, new paradigms are needed to more fully delineate multi-faceted camouflaging/IM, especially for operationalizing and measuring its non-conscious aspects. For example, behavioral priming experiments can gauge camouflaging/IM processes both within and outside conscious awareness98. Dyadic or group interactions coupled with second- and third-party social evaluations provide performance-based assessments of camouflaging/IM effectiveness110. Ecological momentary assessments enable real-time captures of the phenomenological features of camouflaging/IM across real-world, real-time social episodes111,112. Future use of these complementary measures can tackle camouflaging/IM from context-sensitive, objective, and ecologically valid angles, surpassing the limitations of current retrospective self-report tools, to offer a more comprehensive picture of multi-faceted IM and how it manifests across diverse populations and contexts.

While the relationships identified in the current SEM analyses are grounded in theory, they do not entail definitive causal inference. Despite qualitative evidence, no existing quantitative evidence has yet causally linked camouflaging/IM and mental health outcomes4. It is also possible that mental health and camouflaging/IM form a feedback loop: depression and anxiety—initially resulting from camouflaging/IM—may become reinforcing factors that drive further camouflaging as individuals conceal their mental health struggles3. Our cross-sectional data preclude this mechanistic assessment. Such a feedback mechanism might also extend to the socio-motivational factors. Internalized stigma and unmet social belonging needs may initially motivate camouflaging/IM, yet the behavior itself can perpetuate feelings of disconnection and reinforce internalized stigma that drive further camouflaging/IM. This dilemma may be especially prevalent among marginalized groups across domains such as ethnicity, language, sexual and gender diversity, and neurodivergence; it must be unraveled to clarify the conditions that shape camouflaging/IM, attitudes towards its use, and wellbeing outcomes among these groups. Longitudinal studies during key developmental stages such as late childhood and adolescence can provide crucial developmental insights.

Critical factors not assessed in this study are the immediate contextual and distal (e.g., cultural) social influences on camouflaging/IM. Although a general population-based sample enhances the study’s representativeness, it limits our ability to capture cultural nuances and intersectionality. Given that camouflaging/IM involves efforts to blend into the surrounding majority sociocultural context, these strategies are inherently culturally dependent. For example, the growing global research on the CAT-Q has revealed differences in its factor structure and validity in East Asian countries like Taiwan and Japan113,114. In collectivist-prone, face-oriented cultures115, camouflaging/IM may be ingrained in its conformity-oriented social norms and influence mental health in complex ways. On one hand, camouflaging/IM might impose generally fewer mental health costs in these cultures as it is more normalized, widely practiced, and enacted with lower cognitive load116. On the other hand, pervasive social comparison and stringent social expectations could intensify the stakes of camouflaging/IM and its mental health impacts, especially in vulnerable groups such as autistic people. Future research should treat cultural and social contextual differences as essential determinants when considering the transactional nature of IM101.

Other limitations of this study warrant discussion. Given the large-scale survey study format, we only assessed perspective-taking and executive functioning via self-report questionnaires. The IRI-PT subscale and AEFI were used considering their advantages as brief, psychometrically sound instruments that assess corresponding cognitive functions in the context of daily-life behaviors, as perceived by the participants themselves. Nonetheless, we warrant caution in interpreting the findings, which only reflect links between self-perceived (rather than performance-based) cognitive capabilities and IM facets. Future camouflaging/IM research using performance-based cognitive measures are needed to complement the current findings. Another limitation relates to the use of self-reported, dimensional indices of neurodivergent traits. The observed moderation effects of autistic and ADHD traits may not be the same as those of categorical and clinical autism and ADHD diagnoses. To establish generalizability—and to truly harmonize camouflaging with broader IM experiences across human groups—future research should evaluate whether the same IM facets and associated mechanisms can be unveiled in clinically diagnosed individuals.

This study has practical implications for supporting neurodivergent, especially autistic, individuals. For example, although some social skills programs for autistic people incorporate training in contextual awareness and social inference117, the emphasis largely remains on behavior scaffolding, which may inadvertently encourage camouflaging22,118. Our findings suggest that simply increasing the intentional use or frequency of camouflaging/IM may negatively impact mental health. Environment-focused support is needed to change neurotypical social spaces and promote community bridging, which could concurrently reduce the mental health impacts of internalized stigma, social exclusion, and pervasive camouflaging/IM119. Careful refinements can also be made to common behavior-based intervention models. By reconsidering camouflaging and related social coping skills within the transactional IM framework, interventionists can draw from a wider array of social adjustment strategies established in IM research to promote person-environment fit120,121. It is crucial to extract strategies that are applicable to neurodivergent people and to distinguish between clinically valuable versus suboptimal ones. For instance, incorporating context-tailored, adaptive self-presentation techniques may enhance autistic adolescents’ and adults’ self-efficacy, agency, and creativity in navigating social interactions. Conversely, self-suppressive strategies that autistic individuals may internalize as compelled “proper” behavior should be de-emphasized14. Integrating camouflaging and IM research into support models for neurodivergent people could facilitate meaningful improvements in social adaptation while preserving one’s sense of self, agency, pride, and wellbeing.

Conclusion

This study examined camouflaging within the broader context of IM and provided initial empirical support for the transactional IM framework. The findings suggest that IM, which includes camouflaging, is a multi-faceted construct. The intentional use of strategies to manage one’s impression reflects a universal human drive, although the degree to which IM is compelled across human groups depends on factors such as social stigma and belonging needs. We also show that IM intentional use is distinct from one’s self-perceived ability to manage impressions effectively. IM intentional use and IM self-efficacy are differently associated with socio-motivational and cognitive enablers, and the two facets interact to shape mental health. Camouflaging/IM further manifests in partly neurodivergence-dependent ways. Longitudinal, experimental, and interventional studies are needed to better understand these mechanisms and establish causal inference. These insights offer key directions for future research and support model development, highlighting opportunities to foster agency, positive self-growth, and life satisfaction across the neurodiverse human population.

Methods

Participants

The study initially included 1,051 adults aged 18 years and older who were capable of self-reporting and providing consent. Recruitment occurred over 26 days using Prolific, an online crowdsourcing site where users volunteer for web-based studies in exchange for monetary compensation. Participants were paid USD $9.50 per hour. The recruitment utilized US general population representative sampling, an algorithm provided by Prolific based on US census data and stratified by age, ethnicity, and sex. Five participants were excluded from the analyses due to implausible age reporting or failing attention checks, and 74 were excluded due to incomplete data. These data exclusion criteria were determined a priori. The final analyzed sample included 972 participants with complete item-level data. This sample consisted of 461 men (self-identified cisgender), 491 women (self-identified cisgender), 17 gender-diverse individuals, and 3 who preferred not to report their gender, with an average age of 44.2 years (range 18 to 90, median 43). Additionally, 72.7% identified as Caucasian, and 7.51% identified as neurodivergent (Table 1). This same sample has previously been used to assess the dimensional structure of the CAT-Q in the general population and its psychological correlates17,18.

Following the resource constraint approach122, this sample size was the largest attainable given the available study resources. Generalized guidelines regarding sample size are difficult to develop for structural equation modeling (SEM), which was the main analysis. The current sample size is above the conventional minimum recommendation of 200 participants123,124,125, which is based on different ratios of numbers of indicator to latent variables126. However, it is below the more recent recommendations of 20:1 observation to parameter ratio127. Adjustments to the model specification were made due to this consideration (see Analysis 2 below).

Procedure and measures

The study design, procedure, and measures were all in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and approved by the Research Ethics Board at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), Toronto, Canada (REB # 079/2021). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study. Participants completed an online survey hosted on the Qualtrics platform, which took an average of 54 min to complete. The survey included a demographic questionnaire and a series of self-report measures that assessed camouflaging and IM constructs, neurodivergent traits, socio-motivational and cognitive variables, and mental health. These measures were selected for their suitability for an online format, brevity, strong psychometric properties, and relevance to key constructs in the transactional IM framework3 (see Supplemental Materials for details on the measures and their psychometrics). All measures analyzed in this study were publicly available for non-commercial, scientific use. To ensure data quality, Prolific employs fraud detection, including strict sign-up verification and monitoring for unusual user activity (https://www.prolific.com/blog/bots-and-data-quality-on-crowdsourcing-platforms).

The CAT-Q5 and the Compensation Checklist (COMP)19 were used to measure camouflaging, and the Self-Presentation Tactics scale (SPT)9 was used to measure the extent people employed different types of self-presentation strategies. The Self-Concealment Scale (SCS)10 measured the extent people conceal negative or distressing personal information, and the revised Self-Monitoring Scale (SMS)11 measured individuals’ subjective ability to modify how they are perceived by others. Regarding neurodivergence, the Subthreshold Autism Trait Questionnaire (SATQ)79 and the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale Part A (ASRS-A)80 were used to measure autistic and ADHD traits, respectively.

Measurements of socio-motivational constructs that are theoretically relevant to the transactional IM framework included the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire Thwarted Belongingness subscale (INQ-TB)82 to measure social belonging needs, the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS)81 to measure social anxiety and avoidance, and the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Inventory 10-item version (ISMI-10)61 to measure self-reported internalized stigma. The ISMI-10 was adapted for the general population, whereby participants reported the most salient minority group that they belong to (e.g., concerning gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, atypical hobbies or interests, physical or mental disabilities), and based their reports of internalized stigma-related experiences on this minority identity. Self-perceived cognitive features included executive functioning as measured by the Amsterdam Executive Functions Inventory (AEFI)83, behavioral inhibition as measured by the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Brief Version (BIS-BRIEF)84, and perspective-taking as measured by the Interpersonal Reactivity Index Perspective-Taking subscale (IRI-PT)85. We used only the PT subscale of the IRI to target one’s self-perceived ability to adopt other’s psychological worldviews in daily situations85, a construct likely central to social decoding and IM decisions3. Measurements for mental health included the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7)86 for generalized anxiety symptoms, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)87 for depressive symptoms, the Self-Regulatory Fatigue Scale Short Form (SRF-S)88 for cognitive exhaustion, and the Kernis-Goldman Authenticity Inventory Short Form (KGAI-SF)89 as well as the Self-Concept Clarity (SCC) scale90 for subjective authenticity.

Statistical analyses overview

There were no missing item-level data for any of the analyses performed. Total scale scores for each construct measure were computed by summing all item scores. For construct measures with subscales, we computed subscale scores by summing all corresponding item scores for that subscale. Items were reverse-coded when needed. All continuous variables were standardized to z-scores. No variable showed notable skewness. Assumption of linearity was confirmed via visual inspection of the correlation scatterplots of all variables. The Breusch-Pagan test suggested no heteroscedasticity in the data128. Although the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality was significant, we further assessed normality of residuals via visual inspection of the density and Q-Q plots. The datapoints for all variables did not deviate far from the reference line. As the data may be partially non-normally distributed, adjustments were made during the SEM specification (see Analysis 2).

Following the two objectives, two sets of analyses were conducted sequentially. We first examined how camouflaging fits into the overall IM profile. We evaluated how IM-related constructs (i.e., camouflaging, compensation, self-presentation, self-concealment, self-monitoring) are associated with each other and with different factors across social motivation, cognition, and mental health. First, we used joint exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to identify the latent facet structure of different IM construct measures. Second, we used the identified IM facets to test a SEM that empirically evaluated the transactional IM framework3. The SEM examined how different IM facets are associated with theoretical socio-motivational and cognitive antecedents, and different mental health consequences. Additionally, we assessed how these paths are moderated by autistic and ADHD traits, as well as how identified latent IM facets interact in their relations to mental health. Although the SEM assumes directionality in the relationship paths, the cross-sectional nature of our data means that the current set of analyses cannot establish directionality or causality of the effects. All analyses were performed in R version 4.2.1.

Analysis 1: joint exploratory factor analysis identifying latent IM facets underlying camouflaging/IM constructs

We first computed a Pearson correlation matrix using the full sample to observe whether different IM measures show different patterns of association among themselves and with other socio-motivational, cognitive, and mental health variables. The total scale score of each construct measure was entered into the correlation analyses. This initial step offered preliminary insights on potential facet patterns among camouflaging/IM measures. Then, we conducted a joint EFA on the total scale scores of all camouflaging/IM measures. Joint factor analysis across validated measures is an established technique in several fields of psychology to elucidate the latent factor structure of constructs such as personality functioning and executive functions129,130,131. In the current dataset, the CAT-Q, COMP, SPT, SCS, and SMS were all internally consistent with good to excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α ranged from 0.83 to 0.97).

We first visualized the eigenvalues of the principal components derived from camouflaging/IM measures in a screeplot. Using the elbow method, we identified two components as the optimal solution. We then performed the joint EFA with the oblimin oblique rotation using the fa function of the psych R package132,133. The joint EFA allowed us to directly assess how the facets of IM were captured by different camouflaging/IM measures. We made the a priori decision to randomly assign 50% of the sample to the joint EFA to delineate latent IM facets. We subsequently used the entire sample to maximize statistical power when validating the derived IM facet structure via a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which was embedded within the full SEM (see Analysis 2).

Analysis 2: structural equation model of IM facets, socio-motivational, cognitive, and mental health factors

We conducted SEM using the full sample (N = 972) to estimate the predicted relations among the identified IM facets and socio-motivational, cognitive, and mental health variables, as theorized by the transactional IM framework3. Following the results of Analysis 1, we specified two IM latent variables: IM intentional use and IM self-efficacy. Latent cognitive variables included executive functioning and perspective-taking, and latent socio-motivational variables included social belonging needs, internalized stigma, and social anxiety. Latent mental health variables included affective symptoms, fatigue, and authenticity. All latent variables were reflective. For the full model specification information on latent and indicator variables, see Table 2.

Given the number of latent variables and potential model parameters, we balanced practical feasibility of model estimation by limiting the number of indicator variables but also maintaining well-reflected latent variables with as much analytical resolution as possible. To ensure that each latent variable was identifiable, we followed recommended guidelines to have at least two indicators per latent variable127,134. To minimize model complexity, we used the following specification procedure: (1) We used total scale scores as indicators where more than two scales reflect a latent construct (e.g., AEFI and BIS-BRIEF reflected executive functioning; therefore, the total scale score of AEFI and that of BIS-BRIEF were two indicators of executive functioning); (2) we avoided using single-item indicators when only one scale reflected a latent construct—hence, we used subscale scores when available (e.g., LSAS avoidance and anxiety subscale scores reflected social anxiety), and we used item-level scores when the selected measure was unidimensional (e.g., IRI-PT item scores reflected perspective-taking). Model fit was assessed using multiple indices, with the following cut-off values indicating an acceptable to good fit: robust comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ 0.90, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.08, and robust root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.06125.

We first assessed the measurement model of all theoretical latent constructs through a CFA. A few principles guided our decisions when specifying the optimal measurement model. First, we removed indicators with unacceptable to poor factor loading (< 0.32) or high residual covariance123,124. One item (item 4) from the IRI-PT, two items (items 2 and 9) from the ISMI-10, and the “relational orientation” subscale score from the KGAI-SF were dropped based on these criteria. The “relational orientation” subscale from the KGAI-SF measures whether one expresses themselves authentically with close others rather than an intrapersonal sense of authenticity89. Two items from the CAT-Q (items 12 and 24) were dropped a priori based on previous instrument validation study using the same general population sample17, whereby these items did not load onto any of the three factors of the CAT-Q. The final fit of the CFA was assessed, and all factor loadings were confirmed to be at least minimally salient (i.e., above 0.32)123,124 before we proceeded to adding theoretical structural and mediation paths to develop the full SEM.

For structural paths, we specified executive functioning, perspective-taking, social belonging needs, internalized stigma, and social anxiety as the cognitive and socio-motivational latent predictors of IM intentional use and self-efficacy. We also specified IM intentional use, IM self-efficacy, social belonging needs, and internalized stigma as latent predictors of mental health variables (including affective symptoms, fatigue, and authenticity). For all structural and covariance paths, see Table 3. The SEM was estimated using the maximum likelihood with robust standard errors estimator due to potential data non-normality. This was done using the sem function of the lavaan R package135. After initial model estimation, we incorporated sparing model modifications into the final SEM to account for additional, theoretically viable relations among the indicator variables based on inspection of modification indices. Specifically, we allowed for estimation of residual covariances among indicators from the same scale to account for shared method variance (e.g., similar or reversed item wording)134. Finally, we included simple mediation paths to assess, firstly, the indirect effects from internalized stigma and social belonging needs to both IM intentional use and self-efficacy through social anxiety, and secondly, the indirect effects from internalized stigma and social belonging needs to mental health through both IM intentional use and self-efficacy. Social anxiety and the two IM facets were deemed significant mediators if the 95% confidence intervals of the indirect effect estimates excluded 0. The confidence intervals were computed via the delta method given our use of the robust maximum likelihood estimator function for the overall SEM.

After the model was confirmed, we nested it within three new models to examine additional latent interaction effects136. We first tested two models that added the moderation effects of autistic and ADHD traits respectively on all structural paths predicting IM intentional use and self-efficacy, as well as on the structural paths predicting affective symptoms, fatigue, and authenticity by IM intentional use and self-efficacy. We then tested a third model that included the latent interactions between IM intentional use and self-efficacy in predicting affective symptoms, fatigue, and authenticity. Latent interaction terms (e.g., between IM intentional use and self-efficacy) were created via aggregating the product terms of their corresponding observed indicators using the indProd function in the semTools R package135,137. The indicator variables were double-mean centered138, once prior to creating the product terms and again prior to fitting the model with the latent interactions. The model fit of the additional SEM with latent interactions were not interpreted as these indices would be skewed136.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request at [mengchuan.lai@utoronto.ca].

References

Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self In Everyday Life. In Social Theory Re-Wired (Routledge, 2023).

Leary, M. R. & Kowalski, R. M. Impression management: A literature review and two- component model. Psychol. Bull. 107, 34–47 (1990).

Ai, W., Cunningham, W. A. & Lai, M. C. Reconsidering autistic ‘camouflaging’ as transactional impression management. Trends Cogn. Sci. 26, 631–645 (2022).

Cook, J., Hull, L., Crane, L. & Mandy, W. Camouflaging in autism: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 89, 102080 (2021).

Hull, L. et al. Development and validation of the camouflaging autistic traits questionnaire (CAT-Q). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 819–833 (2019).

Libsack, E. J. et al. A systematic review of passing as non-autistic in autism spectrum disorder. Clin. Child. Fam Psychol. Rev. 24, 783–812 (2021).

Zhuang, S. et al. Psychosocial factors associated with camouflaging in autistic people and its relationship with mental health and well-being: A mixed methods systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 105, 102335 (2023).

Field, S. L., Williams, M. O., Jones, C. R. G. & Fox, J. R. E. A meta-ethnography of autistic people’s experiences of social camouflaging and its relationship with mental health. Autism 28, 1328–1343 (2024).

Lee, S. J., Quigley, B. M., Nesler, M. S., Corbett, A. B. & Tedeschi, J. T. Development of a self-presentation tactics scale. Personal Individ Differ. 26, 701–722 (1999).

Larson, D. G. & Chastain, R. L. Self-concealment: Conceptualization, measurement, and health implications. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 9, 439–455 (1990).

Lennox, R. D. & Wolfe, R. N. Revision of the self-monitoring scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 46, 1349–1364 (1984).

Lawson, W. B. Adaptive morphing and coping with social threat in autism: an autistic perspective. J. Intellect. Disabil. - Diagn. Treat. 8, 519–526 (2020).

Livingston, L. A., Shah, P. & Happé, F. Compensatory strategies below the behavioural surface in autism: A qualitative study. Lancet Psychiatry. 6, 766–777 (2019).

Lawson, W. Adaptive morphing and coping with social threat in autism: an autistic perspective. J. Intellect. Disabil. - Diagn. Treat. 8, 519–526 (2020).

Hannon, B., Mandy, W. & Hull, L. A comparison of methods for measuring camouflaging in autism. Autism Res. 16, 12–29 (2023).

Williams, Z. J. The construct validity of ‘camouflaging’ in autism: Psychometric considerations and recommendations for future research - reflection on Lai et al. (2020). J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 63, 118–121 (2022).

Ai, W., Cunningham, W. A. & Lai, M. C. The dimensional structure of the camouflaging autistic traits questionnaire (CAT-Q) and predictors of camouflaging in a representative general population sample. Compr. Psychiatry. 128, 152434 (2024).

Ai, W., Cunningham, W. A. & Lai, M. C. Camouflaging, internalized stigma, and mental health in the general population. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 70, 1239–1253 (2024).

Livingston, L. A., Shah, P., Milner, V. & Happé, F. Quantifying compensatory strategies in adults with and without diagnosed autism. Mol. Autism. 11, 15 (2020).

Cook, J., Crane, L., Bourne, L., Hull, L. & Mandy, W. Camouflaging in an everyday social context: an interpersonal recall study. Autism 25, 1444–1456 (2021).

Fombonne, E. Camouflage and autism. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 61, 735–738 (2020).

Lai, M. C. et al. Commentary: ‘Camouflaging’ in autistic people – reflection on fombonne (2020). J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 62 (2021).

Petrolini, V., Rodríguez-Armendariz, E. & Vicente, A. Autistic camouflaging across the spectrum. New. Ideas Psychol. 68, 100992 (2023).

van der Putten, W. J. et al. Is camouflaging unique for autism? A comparison of camouflaging between adults with autism and ADHD. Autism Res. 17, 812–823 (2024).

Chapman, L., Rose, K., Hull, L. & Mandy, W. I want to fit in… but I don’t want to change myself fundamentally: A qualitative exploration of the relationship between masking and mental health for autistic teenagers. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 99, 102069 (2022).

Funawatari, R. et al. Camouflaging in autistic adults is modulated by autistic and neurotypical characteristics of interaction partners. J. Autism Dev. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-024-06481-5 (2024).

Lai, M. C., Lin, H. Y. & Ameis, S. H. Towards equitable diagnoses for autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder across sexes and genders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 35, 90 (2022).

Turnley, W. H. & Bolino, M. C. Achieving desired images while avoiding undesired images: exploring the role of self-monitoring in impression management. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 351–360 (2001).

Velikonja, T., Fett, A. K. & Velthorst, E. Patterns of nonsocial and social cognitive functioning in adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 76, 135–151 (2019).

Pachankis, J. E., Mahon, C. P., Jackson, S. D., Fetzner, B. K. & Bränström, R. Sexual orientation concealment and mental health: A conceptual and meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 146, 831–871 (2020).

Pearson, A. & Rose, K. A conceptual analysis of autistic masking: Understanding the narrative of stigma and the illusion of choice. Autism Adulthood. 3, 52–60 (2021).

Leary, M. R. & Baumeister, R. F. The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 32, 1–62 (Academic Press, 2000).

Hull, L., Petrides, K. V. & Mandy, W. Cognitive predictors of self-reported camouflaging in autistic adolescents. Autism Res. 14, 523–532 (2021).

Steinmetz, J., Sezer, O. & Sedikides, C. Impression mismanagement: people as inept self-presenters. Soc. Personal Psychol. Compass. 11, e12321 (2017).

Livingston, L. A., Colvert, E., Team, S. R. S., Bolton, P. & Happé, F. Good social skills despite poor theory of mind: exploring compensation in autism spectrum disorder. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 60, 102–110 (2019).

Lai, M. C. et al. Quantifying and exploring camouflaging in men and women with autism. Autism 21, 690–702 (2017).

Sezer, O. Impression (mis)management: when what you say is not what they hear. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 44, 31–37 (2022).

Farrow, T. F. D., Burgess, J., Wilkinson, I. D. & Hunter, M. D. Neural correlates of self-deception and impression-management. Neuropsychologia 67, 159–174 (2015).

Wang, Y. & de Hamilton, A. F. Social top-down response modulation (STORM): A model of the control of mimicry in social interaction. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6, 153 (2012).

Lai, M. C. et al. Neural self-representation in autistic women and association with ‘compensatory camouflaging’. Autism 23, 1210–1223 (2019).

Stark, E., Stacey, J., Mandy, W., Kringelbach, M. L. & Happé, F. Uncertainty attunement’ has explanatory value in Understanding autistic anxiety. Trends Cogn. Sci. 25, 1011–1012 (2021).

Van de Cruys, S. et al. Precise minds in uncertain worlds: predictive coding in autism. Psychol. Rev. 121, 649–675 (2014).

Murray, D., Lesser, M. & Lawson, W. Attention, monotropism and the diagnostic criteria for autism. Autism 9, 139–156 (2005).

Milton, D. E. M. On the ontological status of autism: the ‘double empathy problem’. Disabil. Soc. 27, 883–887 (2012).

Livingston, L. A. & Happé, F. Conceptualising compensation in neurodevelopmental disorders: reflections from autism spectrum disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 80, 729–742 (2017).

Barrick, M. R., Shaffer, J. A. & DeGrassi, S. W. What you see may not be what you get: relationships among self-presentation tactics and ratings of interview and job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 94, 1394–1411 (2009).

Pryke-Hobbes, A. et al. The workplace masking experiences of autistic, non-autistic neurodivergent and neurotypical adults in the UK. PLOS ONE. 18, e0290001 (2023).

Allen, K. A., Gray, D. L., Baumeister, R. F. & Leary, M. R. The need to belong: A deep dive into the origins, implications, and future of a foundational construct. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 34, 1133–1156 (2022).

Bolino, M., Long, D. & Turnley, W. Impression management in organizations: critical questions, answers, and areas for future research. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 3, 377–406 (2016).

Tierney, S., Burns, J. & Kilbey, E. Looking behind the mask: social coping strategies of girls on the autistic spectrum. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 23, 73–83 (2016).

Alkhaldi, R. S., Sheppard, E. & Mitchell, P. Is there a link between autistic people being perceived unfavorably and having a mind that is difficult to read? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 3973–3982 (2019).

Grossman, R. B., Mertens, J. & Zane, E. Perceptions of self and other: social judgments and gaze patterns to videos of adolescents with and without autism spectrum disorder. Autism 23, 846–857 (2019).

DeBrabander, K. M. et al. Do first impressions of autistic adults differ between autistic and nonautistic observers? Autism Adulthood. 1, 250–257 (2019).

Gurbuz, E., Riby, D. M., South, M. & Hanley, M. Associations between autistic traits, depression, social anxiety and social rejection in autistic and non-autistic adults. Sci. Rep. 14, 9065 (2024).

Quadt, L. et al. I’m trying to reach out, i’m trying to find my people: A mixed-methods investigation of the link between sensory differences, loneliness, and mental health in autistic and nonautistic adults. Autism Adulthood. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2022.0062 (2023).

Newheiser, A. K. & Barreto, M. Hidden costs of hiding stigma: ironic interpersonal consequences of concealing a stigmatized identity in social interactions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 52, 58–70 (2014).

Zhang, M., Barreto, M. & Doyle, D. Stigma-based rejection experiences affect trust in others. Soc. Psychol. Personal Sci. 11, 308–316 (2020).

Maïano, C., Normand, C. L., Salvas, M. C., Moullec, G. & Aimé, A. Prevalence of school bullying among youth with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Res. 9, 601–615 (2016).

Botha, M. & Frost, D. M. Extending the minority stress model to understand mental health problems experienced by the autistic population. Soc. Ment Health. 10, 20–34 (2020).

Weiss, J. A. & Fardella, M. A. Victimization and perpetration experiences of adults with autism. Front. Psychiatry. 9, (2018).

Boyd, J. E., Otilingam, P. G. & DeForge, B. R. Brief version of the internalized stigma of mental illness (ISMI) scale: psychometric properties and relationship to depression, self esteem, recovery orientation, empowerment, and perceived devaluation and discrimination. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 37, 17–23 (2014).

Botha, M., Dibb, B. & Frost, D. M. Autism is me’: an investigation of how autistic individuals make sense of autism and stigma. Disabil. Soc. 37, 427–453 (2022).

Bargiela, S., Steward, R. & Mandy, W. The experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: an investigation of the female autism phenotype. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 46, 3281–3294 (2016).

Pyszkowska, A. It is more anxiousness than role-playing: social camouflaging conceptualization among adults on the autism spectrum compared to persons with social anxiety disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 55, 3154–3166 (2025).