Abstract

The increasing environmental concerns associated with conventional petroleum-based plastics have driven the urgent need to develop sustainable, biodegradable alternatives for packaging applications. This research explores the development of an environmentally friendly and strong bioplastic film. It’s made from avocado seed starch and strengthened with cellulose fibers obtained from the enset pseudostem, offering a potential solution to the environmental problems linked to traditional plastic materials. A Central Composite Design (CCD) was employed to optimize key processing parameters: drying temperature (30–70 °C), glycerol concentration (0.1–0.4 mL/g), and starch-to-cellulose ratio (60:40–90:10%w). The optimal formulation, achieved at a drying temperature of 49 °C, glycerol concentration of 0.23 mL/g, and a starch-to-cellulose ratio of 77:23%w, resulted in a bioplastic film with a tensile strength of 10.49 MPa, Young’s modulus of 265.93 MPa, elongation at break of 8.73%, and 41.37% weight loss after two weeks of soil burial. Structural and physicochemical analyses, including FTIR, SEM, DSC, XRD, and RVA, revealed enhanced intermolecular hydrogen bonding, increased crystallinity (~ 26%), and improved thermal stability, suggesting strong molecular interactions between starch and cellulose. The optimized film exhibited favorable barrier properties, with moisture content of 14.3%, solubility of 16.8%, and water vapor permeability of 2.76 × 10⁻¹⁰ g/Pa·s·m. Furthermore, the films showed increased opacity and compact morphology, making them suitable for light-sensitive packaging applications. The developed composite film is a high-performance, eco-friendly alternative to conventional plastics, particularly in food packaging and other single-use plastic products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Conventional plastics are environmentally problematic due to their slow degradation and production from non-renewable resources like petroleum. Their heavy use in packaging has driven global environmental concerns, leading to the development of natural, renewable, and biodegradable materials. The packaging sector is growing due to this shift. While starch films have a long history of use, their low mechanical strength is a key issue. Recent research focuses on creating biocomposites by adding reinforcements and glycerol to starch polymers to improve their properties1.

In Ethiopia, small-scale farms in regions like Bicolo, West Gojjam, Sidama, and the Southern Nations cultivate avocados. The pulp is used industrially, but starch-rich skin and seeds are often wasted. The avocado seeds have high levels of beneficial compounds2. Despite their potential as starch and pigment sources3, avocado seeds are frequently discarded after pulp processing, causing pollution. Using this organic waste for starch-based films could reduce the environmental issues linked to petroleum-based packaging4. Avocado seed starch typically contains 15–25% amylose and 75–85% amylopectin, with relatively small granule size (5–15 μm) and good film-forming properties but limited mechanical strength5,6.

The Lemat enset plant has wild (seed-propagated) and domesticated (cross-pollinated) forms. It’s a crucial, drought-resistant food source for over 20% of Ethiopia’s southern highlands population7. Processing the Lemat enset (Ensete ventricosum) pseudostem cellulose and corm yields both starchy food and fiber8. Enset pseudostem fibers are characterized by high cellulose content (60–70%), good aspect ratio (length/diameter > 100), and excellent compatibility with starch matrices due to their hydrophilic nature. This fiber is sun-dried and used in rural construction for items like sacks, ropes, and binding materials, replacing nails9.

Biopolymers such as polysaccharides (e.g., cellulose, chitosan), starch, proteins, and lipids are commonly used due to their natural and biodegradable properties. Polysaccharides provide mechanical strength and film-forming ability, starch is tasteless and odorless with selective permeability, and proteins are good for transparency and gas barriers. Lipids improve moisture resistance while plasticizers enhance flexibility without compromising biodegradability10. The mechanical properties of biodegradable films can be enhanced by additives such as cellulose fibers or metal oxides. Antioxidants, antimicrobials, and water vapor permeability modifiers provide additional functional properties to films for food preservation10,11. The functional biodegradable films that incorporate antibacterial agents and natural antioxidants to improve food preservation while maintaining environmental benefits12. Polysaccharides such as cellulose and chitosan are shown to form strong, biodegradable films with enhanced barrier properties through nanocellulose technology and additive incorporation. Starch films’ tensile strength and moisture barrier are linked to amylose content and plasticizer use, supported by data on water vapor permeability and film thickness influencing performance13.

Starch is a popular choice for making biodegradable films in numerous applications due to its renewability, abundance, and low cost. However, bioplastics made solely from starch lack sufficient strength and often need reinforcing agents like glass fibers, clays, and natural fibers. These reinforcements are sometimes byproducts or waste from agricultural sources1. Plant-derived cellulosic fibers and polymers are becoming important raw materials for many uses. This is because they’re better for the environment. Also, when a starch base and cellulose fibers bond strongly, the resulting materials perform well mechanically14.

Natural fibers have been prized for centuries as valuable and environmentally sound materials, thanks to their distinctive qualities. They are replacing costly and environmentally damaging synthetic fibers because they are biodegradable. Growing demand and sustainability are driving research into eco-friendly materials based on readily available plant parts15. Environmental and biodegradability are major concerns in new materials design. Plant fibers from diverse resources may reinforce biopolymers and enhance mechanical performance. The most plentiful natural polymer in plant cell walls, cellulose, gives structural reinforcement16. The novelty of this study lies in the first-time utilization of enset pseudostem cellulose as a reinforcing agent in bioplastic films, uniquely combined with avocado seed starch, optimized through response surface methodology for superior mechanical and barrier properties, and thoroughly characterized via structural, thermal, and morphological analyses of this unprecedented biocomposite system.

Materials and methods

Materials and chemicals

Local juice shops in Addis Ababa provided avocado seed kernels for this study. The reinforcing material, natural ensete (ventricosum) pseudo stem fiber, is available in south nation and nationality region, particularly in Hawassa, which is 274.7 km away from Addis Ababa city. Fresh enset pseudostem (approximately 2 kg) was obtained from a local farmer in Hawassa, cleaned to remove dirt and foreign materials, air-dried for 48 h, and then mechanically defibered using a decorticating machine before chemical treatment. Glycerol was purchased in Kirkos sub city market center, Addis Ababa. Chemicals which were used in the experiment are distilled water, glycerol (99.8%), sodium metabisulfite (Na2S2O5) antioxidant and extracting agent, sodium hydroxide (98%), ethanol (98%), potassium iodide (KI), acetic acid (99.8%) and sulphuric acid (98%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich through local distributor Ethiopian Chemical Supplies, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Methods

Starch extraction

One kg of avocado seeds was peeled, washed, and crushed. A wet miller (Model WM-200, Laboratory Equipment Corp., Addis Ababa) processed them into a fine powder, which was mixed with 2 L water and the antioxidant sodium metabisulfite (0.03% mass/liquor ratio) for 24 h to prevent browning. It was filtered using muslin, settled, and washed using distilled water for starch. After three phases of settlement, starch was then subjected to 10 min of centrifugation at 1200 rpm. The reddish-colored topmost part was then gently scooped off, while residual starch was dried in an oven at a temperature of 50 °C for 24 h duration17. The dried starch was subsequently crushed and sieved to 80 μm for homogeneous size.

Extraction and Preparation of cellulose fiber

Enset fiber was extracted through detergent cleaning, air drying, and pulping 5 g in 300 mL water, followed by filtration and drying. The dried residue underwent alkaline pretreatment with 10% NaOH at a 1:10 ratio (w/v) in a 70 °C water bath for 3 h, then was filtered and washed with hot water to pH 10. The fibers were subsequently treated with 10% acetic acid at 70 °C for 3 h at a 1:10 ratio to achieve delignification and separate cellulose from lignin and hemicellulose, followed by washing to remove residual acid. Bleaching was performed using 10% H₂O₂ in 10% NaOH (1:10 ratio) for 30 min at room temperature and then 30 min at 70 °C, with frequent hot water washing until pure. Finally, the pH was adjusted to 7, the fibers were dried, and the resulting powdered cellulose was sieved through 80 μm to obtain the final product 18,19. Yield of the fiber is calculated using Eq. (1) as follows:

Where Y = yield of fiber, Wi = weight of isolated fiber (g), WS = weight of sample (g).

Yield of starch

Starch yield, on a dry weight basis, is the percentage of starch in the avocado seed sample. The type of seed, extraction agent, and time affect the yield, which is the percentage of starch isolated from the dried kernels20. Yield of the starch is calculated using Eq. (2) as follows:

Where Y = yield of starch, Wi = weight of isolated starch (g), WS = weight of sample (g).

Experimental design and process optimization

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is a statistical approach that helps in planning experiments, creating predictive models, and understanding how different process settings influence the results. An RSM is simple and preferred to other statistical techniques for optimization since it involves fewer experiments21,22. For the experimental design and analysis, Design-Expert version 12.0 was used. To examine response patterns and select the optimum combination of variables, the central composite design (CCD) involving three variables at three different levels was employed. The factor levels were determined through preliminary experiments where we tested wider ranges and selected levels that produced handleable films with measurable properties while avoiding extremes that led to film brittleness or excessive flexibility. Starch and cellulose mixing ratio, glycerol, and film drying temperature were selected as the independent variables. The maximum and minimum values of independent variables (Table 1) were determined as part of the preliminary work for experimental design.

Using statistical software Design-Expert version 12.0, identified the key model that connects the independent components to the response variables. This included a second-order polynomial for a central composite design that eventually resulted in the construction of a quadratic model that included the linear model as given in Eq. (3).

Where; Y is the response variable, A = blending ratio, B = glycerol and C = drying temperature are the codded values of the independent variables, n is the number of independent variables, \(\:\epsilon\:\:\)is the error term, \(\:{\beta\:}_{0}\), \(\:{\beta\:}_{i},\:{\beta\:}_{j\:\:}and\:{\beta\:}_{k\:\:},\:{\beta\:}_{ii},\:\:{\beta\:}_{jj}\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:{\beta\:}_{kk},\:\:{\beta\:}_{ij}\), \(\:{\beta\:}_{ik}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{jk}\) are the constant, linear, quadratic and interaction regression coefficients, respectively.

ANOVA assessed the model’s fit, indicated by R² and adjusted R² values. F and R² values were determined for each response relative to the variables23. Regression coefficients were used to generate 3D surface plots, showing the impact of each variable on the responses while holding others constant. These plots illustrate the main and interaction effects of the variables.

Synthesis of biodegradable films

Biodegradable films were made by solution casting, varying starch-cellulose ratios (90:10 to 60:40 wt%), glycerol (0.1 to 0.4 mL/g), and drying temperatures. Starch (6–9 g) and cellulose (1–4 g) were dissolved in 100 mL water (1:10 ratio). The starch solution was heated to 85℃ at 700 rpm, glycerol was added after 10 min, and the mixture was heated for 20 min. The gel was cooled to 50 ℃ and cast on Petri dishes, then dried at 30–50 ℃ until detached. Films were stored in a desiccator at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) and 50 ± 5% relative humidity for 48 h before testing to ensure equilibrium moisture content for analysis1.

Characterization of barrier properties of biodegradable films

Moisture content

Each sample had its moisture content determined through careful weighing of the films and subsequent oven drying in a 105 °C oven for about 6 h. After the films had attained constant weight (dry weight), moisture content was expressed as a percentage loss in mass based on Eq. (4)24.

Where, MC = moisture content, W1 = initial weight of sample (g), W2 = final weight of sample (g).

Solubility

Solubility was estimated for the deposited films by soaking a weighed 2 cm x 2 cm sample in 50 mL of distilled water in a protected beaker for 24 h under room temperature. The sample was then dried in an oven at 105 °C until it stabilized in weight. The solubility was then computed using Eq. (5)24.

Where, S = Solubility, Wi = initial dry weight (g), Wf = final dry weight (g).

Thickness

A digital micro-meter which has an accuracy of ± 0.001 mm is employed to measure the thickness of the biodegradable film. Five spots on the avocado seed starch-based films were measured using it. To calculate the overall thickness of the resultant starch-based films, they computed an average of these five readings24.

Density

The density of the optimum film was analyzed based on the ASTM D792-91 standard25. The film was sized 2 × 2 cm and weighed (g) on an analytical balance before soaking it in 30 mL distilled water. The amount of fluid displaced after putting the film into the liquid was measured and the film density (ρ) was calculated using Eq. (6).

Where, ρ = density (g/cm3), M = mass (g), V = volume (cm3).

Transparency

For optical transparency measurement preparation, the film sample was cut into small rectangles. One was then inserted inside the spectrophotometer test cell, placing air as a comparison point. The equipment then scanned the sample using light in wavelengths from 200 to 800 nm, as mentioned by Ahmad et al., 201526, through a UV-visible spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Japan). Lastly, the transparency of the film, particularly for a wavelength of 620 nm, was computed through Eq. (7).

T = transparency, T620 = fractional transmittance at 620 nm, X = film thickness (mm).

Water vapor permeability

To determine how readily moisture would pass through the film samples, the gravimetric approach was employed based on the usual procedure in ASTM E96 27 The film samples were sealed carefully on top of a tiny glass cup of silica gel that desiccates the air inside it (10% relative humidity). These cups were then placed in a sealed vessel (a desiccator) flooded with distilled water, producing a highly humid environment (100% relative humidity), and the temperature was maintained constant at 22 °C.

Over a period of two days, the weight of each cup was recorded at regular intervals: 0, 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, and 48 h. The increase in weight due to water vapor permeating the film was measured. To determine how quickly moisture moved through the film, the recorded weight changes over time were analyzed using linear regression. This process generated a line, and its slope indicated the rate of permeation. Ultimately, the film’s water vapor permeability, expressed in g.m⁻¹s⁻¹Pa⁻¹, was calculated using Eq. (8).

Where; WVP = water vapor permeability, G = w/t (g/h) corresponds to the mass of the water absorbed by the system of the time intervals of 8 h, X = average thickness of the biodegradable plastic film, A = the permeation area, and ΔP is the difference between the partial vapor pressure of the atmosphere with silica gel and pure water (52.64 kPa at 22 °C).

Mechanical properties of the films

Tensile strength

Tensile properties followed ASTM D882-10. Film samples (100 mm by 20 mm) were tested for how strong they are when pulled (tensile strength in MPa), how much they stretch before breaking (elongation at break in %, (Eq. (8A))), and how stiff they are (Young’s modulus, (Eq. (8B))). Tests were done at room temperature, 50% humidity, and a speed of 5 mm per min. Thickness helped find the area. A universal Testing machine measured these (ASTM D882-10) using Eq. (9).

Where, TS = tensile strength (MPa), F = force (N), A (mm2) = area (width in mm* thickness in mm) of the sample film

where L is length at break and L₀ is initial length.

where σ is stress, ε is strain, F is force, A is cross-sectional area, and ΔL is change in length.

Weight loss of the films

Weight loss of the film followed ASTM D5988-03a via soil burial. Film squares (5 cm x 5 cm) were oven-dried, weighed (W1), and buried 10 cm deep in the soil (moistened every other day) for 15 days. Samples were then washed, dried at 60 °C, and reweighed (W2) after reaching constant weight in a desiccator28. The percentage of weight loss (%WL) was then calculated using Eq. (12).

WL = Weight loss, W1 = initial weight (g), W2 = final weight (g).

Structural characterization of starch based biodegradable film

Functional group analysis

FTIR (Thermo Scientific iS50, ABX, USA) determined functional groups, band intensities, stretching vibration, and absorption peaks in powders using a potassium bromide (KBr) beam splitter method adapted from Sudheesh et al., 201929. To prepare the samples, the powder was combined and ground with 200 mg of KBr powder at a ratio of 1:100. Measurements were then conducted across the range of 4000 to 400 cm⁻¹ to identify the present functional groups. Spectral data (transmittance vs. wave number) was exported as an Excel file and graphed using Origin 18.0 software (Origin Lab Co., Massachusetts, USA).

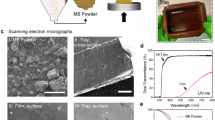

Morphological analysis

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to show the morphological structure30 of the avocado seed cellulose reinforced starch-based biodegradable films (Stereo scan 250 MK3, Cambridge, Japan). The instrument was operated under the following conditions: working distance of 6–13 mm, accelerating voltage of 5–20 keV, and emission current of 75–80 A.

Crystallinity analysis

X-ray patterns of starch-based film-reinforced cellulose were examined using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD-7000, SHIMADZU corporation, Japan) previously provided by Huang et al., 201631. The same protocol was applied since the starch was previously described. XRD analysis was performed at 40 kV and 30 mA, with 2θ ranging from 10° to 40° at a scan rate of 2°/min. The total area under the curve and each peak identified were computed using OriginPro 2018 software. Crystallinity was calculated using the peak deconvolution method: \({\text{Crystallinity }}\left( \% \right){\text{ }}={\text{ }}\left( {{\text{Crystalline area}}} \right)/\left( {{\text{Total area}}} \right) \times {\text{1}}00\)

Thermal analysis

Thermal analysis of the starch film used a DSC (SKZ1052, China), following Lim & Gong (2018)32. A 20 mg film sample in a sealed crucible was heated from 20 to 600 °C at 10 °C/min under nitrogen (50 mL/min), with an empty holder as reference. Origin Pro software analyzed the film’s thermal properties.

Statistical analysis

In all experiments, three identical samples were tested to ensure reliability. The findings are presented as average values, along with their standard deviation (SD) to show the data’s spread. To see if there were any significant differences between the results, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out in addition. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were computed using Expert Design version 12.0 software, which shows the associations among all properties measured. The statistical analyses were carried out using a 95% confidence level, which signifies that a high level of certainty has been achieved in conclusion.

Results and discussion

Yield of starch and fiber extraction

The amount of starch obtained from extraction is primarily influenced by the type of raw material, the substance used for extraction, and the duration of the process. In this study, the starch yield from avocado seeds was measured at 18.34 ± 0.02%. This value shows a slight difference compared to the 19% reported by Macena et al., 202033 and a more significant deviation from the 24.4% found by Bahru et al., 201934. The lower yield compared to Bahru et al. (2019) can be attributed to our use of sodium metabisulfite as an antioxidant, which may form complexes with starch molecules, reducing extractable yield. Extraction yield could be improved by optimizing extraction time, using enzyme pretreatment, or adjusting pH during extraction, though this might affect starch quality. This variation could be attributed to the fact that starch extracted from waste avocado seeds tends to yield less compared to conventional starch sources like cassava, likely due to the inherent characteristics of the starch itself. However, the yield observed in this study falls within the broader range of (18.00–29.33%) reported by de Souza et al., 202135. The yield of the fiber in the study is 45.2 ± 2.1%.

Response surface methodology analysis

Response surface methodology optimized biodegradable film parameters (starch/cellulose ratio, glycerol, drying temperature) for tensile strength, Young’s modulus, elongation at break, and weight loss using a 20-run central composite design. Preliminary experiments defined variable ranges (Table 1). Temperature significantly influenced film properties of strength and flexibility. It initially increased then slightly decreased from 20 to 80 °C. Glycerol concentration (0.1–0.7 mL/g, constant blend/temp) decreased strength/modulus but increased flexibility/weight loss likely due to starch suspension interaction. Cellulose fiber concentration (20–60% w) initially improved strength/flexibility but then decreased possibly related to its interaction within the starch.

Statistical analysis and model fitting

A statistical method called ANOVA was used to check how well the model predicts the material’s strength, stretchiness, and how it breaks down. The ANOVA results showed high F-values for each response model (316.12, 511.94, 83.50, and 415.36 respectively), all with very low p-values (< 0.0001). and very low p-values (< 0.0001) show the model is reliable and the factors tested significantly influence the results. Further testing showed the model closely matches the actual experimental data, as seen in Fig. 1.

Model equations

Table 2 shows the second-degree polynomial equations we developed using a central composite design. These equations link the process variables (from our experiments) to the material’s properties: strength, stiffness, stretchiness, and how it breaks down. We used a quadratic model to find the best fit for the data, and Eqs. (10–13) show these relationships using coded factors.

Where: A, B, and C are blending ratio, glycerol, and drying temperature respectively.

Model summary statistics and analysis of variance (ANOVA)

To determine the most appropriate model, ANOVA and model summary statistics were used for the evaluation of various models. As evident from Tables 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7, the quadratic model consistently had the best R², adjusted R², predicted R², and PRESS values for all measured responses: tensile strength, Young’s modulus, break elongation, and weight loss. The fit summary results also revealed that the quadratic model was the highest recommended among compared models. From the summary statistics, the quadratic model had the best adjusted R² and predicted R², while the cubic model was considered not reliable due to aliasing. The ANOVA analysis revealed significant F-values for the quadratic model for each response: 316.12 for tensile strength, 511.94 for Young’s modulus, 83.50 for elongation at break, and 415.36 for weight loss, all associated with a p < 0.0001.

Tables 4 and 5 present the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for tensile strength and Young’s modulus. The Model F-values of 316.12 and 511.94, respectively, indicate that the models are statistically significant. There’s only a 0.01% probability that such large F-values could arise purely by chance. P-values below 0.0500 signify that specific terms within the model are important. In these cases, the terms A, B, C, AB, AC, BC, A², B², and C² are identified as significant contributors to the model. Conversely, p-values exceeding 0.1 suggest that the corresponding model terms are not significant. If a model contains numerous insignificant terms (beyond those needed for hierarchical structure), simplifying the model might lead to improvement. The 2.24 and 1.63 Lack of Fit F-values suggest that the lack of fitness is not significant in comparison to inherent data variability. There is a 19.81% and 30.32% possibility, respectively, that these Lack of Fit F-values are due to random noise. A non-significant lack of fit is preferable since it ensures a good model that can represent data accurately.

Tables 6 and 7 show the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for elongation at break and weight loss. The Model F-values of 83.50 and 415.36, respectively, suggest that the models are significant, with only a 0.01% probability of such large F-values occurring by chance. P < 0.05 indicates significant model terms, which in this case are A, B, C, AC, BC, A², B², and C². Conversely, p > 0.1 suggests insignificant model terms. If a model has many insignificant terms (excluding those needed for hierarchy), simplifying it might be beneficial. The Lack of Fit F-values of 4.9 and 3.94 implies a 5.28% and 7.94% chance, respectively, of these values occurring due to noise. Since this lack of fit values is not significant, the models are considered a good fit for the data.

The interaction effect of parameters on mechanical properties

The effect of parameters on tensile strength

The tensile strength of biodegradable plastic films is one of the crucial aspects defining capacity for resisting outside pressure and for maintaining film integrity against puncture. The tensile strength of avocado seed starch based biodegradable film was achieved in the range of 4.41–11.01 MPa. Figure 2 (a, b) depicted that avocado seed starch based biodegradable plastic films showed increased tensile strength based on increased blending ratio and glycerol. This is due to the formation of inter-molecular hydrogen bonds between cellulose and avocado seed starch which increases the tensile strength36. However, the tensile strength was found to be lower at the initial and extreme value of glycerol and blending ratio. The addition of glycerol content in amounts higher than 0.3 mL/g lowered interactions between films’ molecules due to a reduction in tensile strength. The presence of glycerol can reduce attractive intermolecular forces around polymer chains by decreasing the internal hydrogen bonding of molecules37. The introduction of cellulose content in amounts higher than 25%, in contrast, lowers tensile strength due to particle agglomeration and low binding capability. Consequently, voids emerge on the film’s surface and the film fractures38. The drying temperature, in Fig. 2 (b, c) showed that at the extreme and initial values, the tensile strength decreases. The lower drying temperature likely allowed the film to retain more moisture, leading to a higher relative humidity. This increased moisture content can result in lower tensile strength39. Increased humidity plasticizes the starch matrix by disrupting hydrogen bonds between starch chains, reducing tensile strength. The tensile strength of 10.49 MPa is comparable to some conventional biodegradable plastics like PLA (20–50 MPa) though lower than conventional PE (20–40 MPa). Cellulose contributes to the film’s stiffness due to strong connections between its molecules. Consequently, when there’s less starch and more cellulose, glycerol, and a higher drying temperature cause a decrease in tensile strength.

The effect of parameters on young’s modulus

Young’s modulus describes how stiff a material is and defines it appropriately. It is a measure of stress divided by strain in the linear portion of a stress-strain curve. The stiffness of biodegradable plastic from avocado seed starch was between 25.9 and 276.77 MPa. Figure 3 (a, b) shows the relationship between biodegradable plastic films and the glycerol and the blending ratio. The previous studies revealed that the high value of Young’s modulus resulted from the lower value of glycerol. However, in this study, Young’s modulus increases with the increase of the glycerol, blending ratio, and cellulose. Gradually, Young’s modulus decreases with the lower and extreme value of the independent variables. The Young’s modulus of the avocado seed starch-based biodegradable film decreased with increasing the glycerol content, due to the introduction of discontinuous is in the polymer matrix of the dried film40. Demonstrates clear glycerol plasticizing effects with tensile strength and modulus decreasing significantly from 9.34 to 1.95 MPa and 620.79 to 36.08 MPa respectively41. The decrease in Young’s modulus of glycerol based nanocomposite film with increasing concentration of the cellulose fiber, while without crystalline cellulose fiber becomes increased42. Thus, the high drying temperature causes the biodegradable plastic to crack easily, and the low drying temperature causes moisture content, which affects the Young’s modulus of the film43. The lower and higher values of the glycerol accounted for the decrease in Young’s modulus.

The effect of parameters on elongation at break

Elongation at break is the extendibility of film length from the initial length to the point of break. Using this parameter elongation at break the stretchability of the biodegradable film was assessed. The desired flexibility of biodegradable packaging film depends on their intended application and subsequent transportation, handling and storage of packaged foods.

The flexibility of the cellulose-reinforced, avocado seed starch-based biodegradable film, as measured by its elongation at break, varied between 3.23% and 8.27%. Figures 4 (a), (b) and (c) illustrate how the amount of glycerol, the blending ratio of the materials, and the drying temperature influenced this property. The findings indicate that increasing the concentration of both cellulose and glycerol led to a decrease in the film’s ability to stretch before breaking. The lower elongation values observed with higher cellulose content might be because more cellulose reduces the attractive forces between the starch molecules and encourages them to clump together44. This aligns with previous research45 showing that adding more cellulose generally makes such films less flexible. The reduction in elongation at break upon adding more cellulose to the avocado seed starch-based biodegradable plastic films could be due to cellulose particles clumping with starch molecules and forming weaker connections between them.

The effect of parameters on weight loss

Film weight loss was tested for two weeks using moistened and non-sterile soil burial methods. One of the most used methods for determining the weight loss of polymeric films is the soil burial method46. The weight loss of reinforced avocado seed starch based biodegradable plastic film was found in the range between 30.7 and 40.7%. Figure 5 (a, b) illustrates the effect of glycerol, blend ratio and drying temperature on film weight loss. The biodegradation rate of the film increases as film cellulose content increases gradually. The increase in the rate of biodegradation may be due to the formation of cellulose molecules’ agglomeration and thus this results in the formation of voids inside the films44. Yet, the weight loss of film drops off in the lower concentration of glycerol and cellulose. This might be because the smaller amount of cellulose fiber leads to high compactness inside and between film chains. While our measurement primarily indicates weight loss, we assume this represents weight loss based on visual observation of film degradation and soil microbial activity. Future studies should include CO₂ evolution measurements to confirm true biodegradation.

Optimum conditions and model validation

The optimal values of the independent variables obtained through numerical optimization were glycerol 0.23 mL/g, blending ratio 77%w, and drying temperature 49 ℃ having optimum response values tensile strength 10.82 MPa, Young’s modulus 268.7 MPa, elongation at break 7.9%, and weight loss 40.4% having desirability 0.963. Reinforced avocado seed starch-based biodegradable film synthesis was optimized to get starch-cellulose plasticized biodegradable plastic film for packaging. Desirability function numerical optimization is used for estimating the composition of a film having optimum properties. Design Expert 12.0 offers different criteria for choosing the desired points for each variable and response, i.e., maximize or minimize the responses. Ideally, the film’s tensile strength should be as high as possible to ensure good packaging integrity for products, a quality enhanced by the reinforcing cellulose mixed with the starch solution. For enhanced environmental sustainability and the flexibility of packaging, the film’s elongation at break and weight loss must surpass those of conventional polyvinyl plastics. To ensure validation of the response surface methodology model predicted optimal conditions, three sets of experimentations were carried out under these optimum conditions as elucidated in Table 8.

Characterization of barrier and mechanical properties of films

A comparison of cellulose reinforced avocado seed starch based biodegradable film with the non-reinforced avocado seed starch biodegradable film is shown in Table 9. The solubility of non-reinforced avocado seed starch based biodegradable films exhibited a higher value than the cellulose reinforced biodegradable films of the same material. Potential use may demand water resistance and non-solubility packaging to enhance the integrity of the products. The non-reinforced avocado seed starch film in this study had higher water vapor permeability than that strengthened by cellulose fibers. The same has been reported in findings for other traditional synthetic plastic films47. The interaction between cellulose and starch granules may create a strong hydrogen bond for this. The tensile strength of reinforced avocado seed starch proved to be superior compared to non-reinforced films and microcrystalline-avocado seed starch film which was reported48. The reinforced film shows lower weight loss because cellulose fibers create a more compact, cross-linked structure that is more resistant to microbial attack compared to the looser structure of pure starch films. However, the reinforced avocado seed starch based biodegradable film Young’s modulus value was observed higher than the non-reinforced films. This might be due to hydrogen bonds formed between the hydroxyl (OH) groups of starch molecules, and the hydroxyl and carboxyl (COOH) groups of cellulose molecules49. The more the Young’s modulus the stiffness of the material is 50.

Moisture content and solubility

Table 9 summarizes the physical parameters of optimally reinforced starch-based biodegradable plastic films. Cellulose provides moisture resistance by forming a physical barrier network within the starch matrix and by its inherently lower hygroscopicity compared to starch, consistently reported by Marichelvam et al. (2019)51. Increased glycerol enhanced moisture uptake due to its hygroscopic nature and -OH groups forming hydrogen bonds with water52,53. However, higher cellulose content reduced moisture absorption as micro-cellulose particles form a strong network, limiting water inclination54. The lower moisture content compared to de Moraes Crizel et al. (2016)55 may be due to cellulose imparting greater moisture resistance.

The optimal reinforced film (23% cellulose, 0.23 mL/g glycerol) showed 16.8% water solubility (± 0.072), aligning56. Decreased solubility with higher cellulose suggests cellulose-reinforced films are less water-soluble than glycerol-reinforced ones. Cellulose’s network formation via hydrogen bonds increases the starch matrix’s cohesiveness, reducing solubility by holding water rather than dissolving on the surface57. This improved water resistance is crucial for applications like food protection.

Film thickness

Film thickness represents a crucial factor when determining both mechanical and physiochemical characteristics. Processing conditions and drying methodologies significantly impact film thickness measurements. Research demonstrates that increasing cellulose content correlates with decreased film thickness, while excessive filler materials result in particle aggregations58. The formation of voids occurs due to high cellulose particle aggregation, which creates poor surface contact area and results in weak interfacial adhesion between fillers and matrix fillers59. Studies revealed that optimal reinforcement occurred at 23% cellulose with 0.23 mL/g glycerol, yielding an average thickness of 0.174 ± 0.034 mm. The findings indicate lower thickness measurements compared to research by de Moraes Crizel et al. (2016)55., potentially attributed to optimal reinforcement material quantities. Glycerol concentration exhibits a direct relationship with film thickness, attributed to enhanced swelling properties and micro-void filling capabilities that increase inter-particle density23. These measurements align with findings reported by Souza de Miranda et al. (2015)60, possibly explained by how continued cellulose content increases lead to particle aggregation, subsequently reducing film thickness through void creation61. The thickness of 0.174 mm makes this film suitable for light-duty packaging applications such as food wraps, disposable bags for dry goods, and agricultural mulch films where moderate thickness provides adequate protection.

Film density

Increasing the amount of fillers such as clays, fibers, calcium carbonate and shell powders increases the density of the film62. This might be due to the addition of cellulose and the incorporation of starch molecules. Adding more plasticizers made the film thicker, wetter, and more soluble. However, it also made the film less dense and absorb less water63. The density was higher than results reported by Pelissari et al. (2017)64 for banana starch films (1.25 g/cm³), likely due to the presence of cellulose fibers. The density of the reinforced avocado seed starch-based biodegradable was found to be higher than the results64. This might be due to the existence of a small amount of glycerol and an adequate amount of cellulose in the synthesized film.

Transparency

The Transparency testing was performed on optimized formulation and improved attribution. It increased with extremely high cellulose content due to micro-void formation65. Conversely, higher glycerol decreased transmittance at 620 nm, likely because its size and molecular weight hinder light transmission. Optimal transparency (3.52 ± 0.035) occurred at 24% cellulose and 0.23 mL/g glycerol. Lower transmittance signifies higher opacity, potentially offering an excellent barrier against light-induced lipid oxidation66.

Increased glycerol significantly reduced transparency, possibly by increasing film thickness67. Glycerol and cellulose as additives in avocado starch films might enhance opacity. Greater film thickness scatters lighter, causing turbidity and lower brightness. The lower transparency observed compared to Admase et al. (2022)68 could be due to the optimal cellulose and glycerol levels affecting film thickness. Higher viscosity might increase thickness, reducing transparency. The inherent brown color of avocado starch could also contribute to lower paste transparency. While well-dispersed starch granules usually increase transparency, the current biodegradable films are less transparent. This could be due to low starch granule dispersion, cellulose concentration, paste turbidity, glycerol concentration, and amylopectin side chain clusters absorbing light, leading to opacity26.

Water vapor permeability

Water vapor permeability (WVP) measures how easily water vapor passes through a film and is crucial for food packaging to control moisture transfer69. The biodegradable film in this study had a WVP of 2.76 × 10− 10g/Pa.s.m. which differs from findings on avocado seed starch48, sisal fiber reinforced potato starch70, and mango seed starch. It is lower than potato starch films (5.2 × 10⁻¹⁰) but higher than synthetic films like PE (10⁻¹² range). Cellulose fibers (Fiber Yield is 45.2 ± 2.1%.) are promising for packaging due to their oxygen barrier and mechanical properties. Higher crystallinity generally leads to lower WVP. The low WVP can be directly attributed to the 26% crystallinity observed in XRD analysis and enhanced hydrogen bonding confirmed by FTIR spectroscopy, which creates a more ordered structure with reduced free volume for water vapor diffusion. The lower WVP observed in the cellulose-reinforced film might be due to the optimal interaction between cellulose and starch molecules and the blend’s adequate crystallinity.

Films with higher amylose content tend to be stronger but more permeable. The lower amylose content in avocado seed starch might contribute to the lower permeability. Glycerol typically increases WVP in starch films; however, in this study, increased glycerol also decreased Young’s modulus and tensile strength71. The difference in permeability between reinforced and non-reinforced films could stem from film preparation, the ratio of starch to cellulose, and the type of plasticizer used. WVP depends on the film’s hydrophilic/hydrophobic balance72. Hydrophobic regions result from cellulose-starch interactions that reduce free hydroxyl groups and create more ordered crystalline domains. The reinforced avocado seed starch film’s low WVP likely results from a higher proportion of hydrophobic regions within its structure.

Characterization of structural properties of optimized biodegradable film

Morphological analysis of the films

Figure 6 presents scanning electron micrographs depicting the morphological characteristics of reinforced avocado seed biodegradable films. Surface analysis reveals minimal porosity while exhibiting notable aggregations of starch and cellulose granular structures throughout the films surface area. The reinforced films surface topology demonstrates considerable roughness, coarseness, and irregular patterns in its structural formation. These observations align with findings reported by75; though contrasting with Barrera et al. (2013)74 who documented smooth surface characteristics in their starch films. The non-uniform surface characteristics observed in current analyses may be attributed to multiple factors: cellulose fiber concentrations, hydrogen bond interactions between starch matrix and cellulose components, and potential structural modifications during the extraction process of both avocado seed starch granules and cellulose fibers33. The morphological variations observed suggest complex interactions between constituent materials. The large fiber structures visible in SEM images represent cellulose fiber bundles that were not completely individualized during processing, indicating partial fiber dispersion in the matrix.

While the present study was found to be comparable with the results reported75. Adding cellulose fiber to starch, a necessary step in creating biodegradable film changes the tiny structures within avocado seed starch films. Perhaps this happens because the avocado seed starch, enset cellulose, and glycerol work together, forming a solid, connected network of molecules. The film’s good mechanical strength, like how well it can resist being pulled apart, might come from how well the glycerol and cellulose mix with the avocado seed starch and the tightly packed arrangement that makes the film stronger overall76.

Functional group analysis of the reinforced film

The avocado seed starch, glycerol, and cellulose get along in the biodegradable films used to analyze FTIR spectroscopy shown in Fig. 7. When they looked at the results for both films (those with added cellulose and those without), they noticed three main zones in the FTIR readings. The signals below 800 cm− 1 seemed to come from the basic movements within the glucose pyranose ring structure. Meanwhile, the signals between 800 and 1800 cm− 1 pointed to vibrations happening within the glucose molecules themselves.

The 2800–3600 cm− 1 region showed C–H bond stretching, and O–H bond stretching and oscillation, potentially due to the films’ water affinity were observed between 3000 and 3600 cm− 1. Peaks at 2929.80 cm− 1 (reinforced) and 2938.00 cm− 1 (non-reinforced) within the 2800–3000 cm− 1 range indicated symmetric C–H stretching77. The peak at 1749.1 cm− 1 attributed to C = O stretching.

The absorption peaks were similar for both film types, with slight wave number differences at the end. Numerical fluctuations between films suggest increased intermolecular hydrogen bonding due to the cellulose filler. The absence of new peaks (except at the end) in the reinforced film indicates no new chemical reactions between the components, supporting Ibrahim et al. (2019)77.

Sharp peaks at 1010.5 and 1388.3 cm− 1 (reinforced) and 1025.4 and 1324.8 cm− 1 (non-reinforced) were attributed to C-O-H stretching and C-C/C-O coupling, possibly indicating tightly bound water in the reinforced film, consistent with Y. Zhang & Han (2006)78.

Looking closer at the 850 to 400 cm− 1 range, slight variations in how the glucose pyranose ring bent were noticeable. This might be because the cellulose and the softened starch were interacting. Examining these specific groups of atoms is important for figuring out if any new connections formed when the bioplastic was made from starch, glycerol, and cellulose.

Figure 7:

Crystallinity analysis of the film

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to analyze the crystalline and amorphous structures of the biodegradable films. Crystalline regions are characterized by strong peaks, while amorphous regions appear as flat areas in the diffractogram. Figure 8 displays the XRD analysis of the reinforced bioplastic film, revealing three primary peaks at 2θ values of 3.48°, 17°, and 19.7°. The reinforced avocado seed starch exhibited increased crystallinity, likely due to the addition of cellulose to the starch matrix and the interaction between cellulose and starch molecules, a finding supported by Supanakorn et al. (2021)79 and broadly consistent with Domene-López et al. (2019)80. The strong peaks at 3.48° and 19.7° in the reinforced film may indicate strong hydrogen bond interactions between cellulose and starch molecules81.

Conversely, the reinforced avocado seed starch also showed low-intensity or flat peak regions, indicating amorphous zones within the plastic film. This amorphous nature might be attributed to the incorporation of glycerol, which can disrupt the crystallinity of the reinforced bioplastic82. The increase in crystalline peaks with fillers like chitosan, fiber, and clay is often due to molecular miscibility with starch, as is the case with cellulose.

The relative crystallinity of the reinforced avocado seed starch biodegradable film was found to be 26%, a result similar in pattern and range to that reported by Salleh et al. (2009)83.

Thermal analysis of the film

Differential scanning calorimetry, or DSC, is a technique that tracks how much heat a material absorbs or releases as it warms up or cools down. This helps scientists understand the steps involved in a reaction. Figure 9 shows DSC curve for the strengthened biodegradable film. It begins with a heat-absorbing (endothermic) process that starts at room temperature and goes up to 300 °C. The first peak at 90 °C likely indicates water evaporation, and the second peak at 235 °C might be due to volatile components. Above 300 °C, the curve enters an exothermic region with a large peak around 450 °C, attributed to the decomposition of the film’s components: glycerol, cellulose, and starch.

Adding cellulose increases the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the avocado seed starch-based film due to interactions within the matrix. Glycerol decomposes in a single step via evaporation, with maximum degradation around 150 °C. Avocado seed starch granules show two degradation phases: initial water and volatile component loss, followed by a major decomposition step involving molecular structural changes around 450 °C. These findings are broadly supported by J. Chen et al. (2020)81.

Conclusion

Avocado seed starch and enset pseudostem cellulose were used to develop strong, sustainable bioplastic films. Starch properties were analyzed. Film synthesis (starch, cellulose, glycerol) was optimized by varying glycerol, cellulose, and drying temperature. Higher glycerol increased water uptake, while cellulose reduced it and improved strength, weight loss, and heat resistance. Excess glycerol weakened strength but increased stretchiness. Optimal conditions (49 °C, 0.23 mL/g glycerol, 77:23 starch: cellulose) yielded a film with 10.49 MPa tensile strength, 265.93 MPa Young’s modulus, 8.73% elongation, and 41.37% weight loss. The cellulose-reinforced film showed superior strength and reduced stretch compared to other bioplastics, with enhanced thermal stability and crystallinity. The developed bioplastic film shows promise for applications in food packaging (particularly for dry goods and light-sensitive products due to its opacity), agricultural mulch films, disposable cutlery coating, and short-term packaging applications where weight loss is advantageous. The film’s barrier properties make it suitable for moisture-sensitive product packaging. This bioplastic’s barrier properties and weight loss make it promising for industrial packaging, highlighting the potential of agricultural waste for high-performance, sustainable bioplastics.

Data availability

The data sets presented during or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sartika, M., Lubis, M., Harahap, M. B., Afrida, E. & Ginting, M. H. S. Production of bioplastic from avocado seed starch as matrix and microcrystalline cellulose from sugar palm fibers with schweizer’s reagent as solvent. Asian J. Chem. 30, 1051–1056 (2018).

Segovia, F. J., Hidalgo, G. I., Villasante, J., Ramis, X. & Almajano, M. P. Avocado seed: A comparative study of antioxidant content and capacity in protecting oil models from oxidation. Molecules 23, 2421 (2018).

KAHN, V. Characterization of starch isolated from avocado seeds. J. Food Sci. 52, 1646–1648 (1987).

Mohammed, H. N., Beeram, E., Divya, B. J., Pallavi, C. & Demir, H. Current Research in Agricultural and Food Science Vol. 1. (Book Publisher International (a part of SCIENCEDOMAIN International), (2020). https://doi.org/10.9734/bpi/crafs/v1

Martins, S. H. F., Pontes, K. V., Fialho, R. L. & Fakhouri, F. M. Extraction and characterization of the starch present in the avocado seed (Persea Americana mill) for future applications. J. Agric. Food Res. 8, 100303 (2022).

Wang, J., Li, Y., Jin, Z., Cheng, Y. & Physicochemical Morphological, and functional properties of starches isolated from avocado Seeds, a potential source for resistant starch. Biomolecules 12, 1121 (2022).

Borrell, J. S., Biswas, M. K., Goodwin, M. & Blomme, G. Enset in ethiopia: a poorly characterized but resilient starch staple. Ann. Bot. 123, 747–766 (2019).

Berhanu, H. et al. Characterization of crop residues from false banana /Ensete ventricosum/ in Ethiopia in view of a full-resource valorization. PLoS One. 13, e0199422 (2018).

Dube, A. M. Isolation and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from ensete ventricosum pseudo-stem fiber using acid hydrolysis. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-022-02987-z (2022).

Evyan, Y. C. Y., Liew, M. S., Patricia, J., Chong, M. Y. & Zairul, Z. A. Biodegradable food packaging and film: a short review. Food Res. 6, 1–12 (2022).

Wang, Q. et al. A review of multilayer and composite films and coatings for active biodegradable packaging. NPJ Sci. Food. 6, 18 (2022).

Shaikh, S., Yaqoob, M. & Aggarwal, P. An overview of biodegradable packaging in food industry. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 4, 503–520 (2021).

Singh, S. et al. A comprehensive overview of biodegradable packaging films: part I—sources, additives, and Preparation methods. Discover Food. 5, 41 (2025).

Hazrati, K. Z., Sapuan, S. M., Zuhri, M. Y. M. & Jumaidin, R. Preparation and characterization of starch-based biocomposite films reinforced by Dioscorea hispida fibers. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 15, 1342–1355 (2021).

Jaiswal, D., Devnani, G. L., Rajeshkumar, G. & Sanjay, M. R. Review on extraction, characterization, surface treatment and thermal degradation analysis of new cellulosic fibers as sustainable reinforcement in polymer composites. Curr. Res. Green. Sustainable Chem. 5, 100271 (2022).

Gloria Ivette Bolio-López, Genaro Cadenas-Madrigal & Lucien Veleva & Extraction of cellulose fibers from tó leaf petioles. (Calathea lutea) and characterization. Inter. J. Innovative Sci. Eng. Technol., 2, 977–981 (2015).

Cornelia, M. & Christianti, A. Utilization of modified starch from avocado (Persea Americana Mill.) seed in cream soup production. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 102, 012074 (2018).

Temesgen, A. G., Eren, R. & Aykut, Y. Investigation of mechanical properties of a novel green composite developed by using Enset woven fabric and Bioresin materials. Polym. Bull. 81, 4199–4219 (2024).

Gabriel, T., Belete, A. & Syrowatka, F. Extraction and characterization of celluloses from various plant byproducts. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 158, 1248–1258 (2020).

Shahrim, N. A., Sarifuddin, N. & Ismail, H. Extraction and characterization of starch from Mango seeds. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1082, 012019 (2018).

Desai, K. M., Survase, S. A., Saudagar, P. S., Lele, S. S. & Singhal, R. S. Comparison of artificial neural network (ANN) and response surface methodology (RSM) in fermentation media optimization: case study of fermentative production of scleroglucan. Biochem. Eng. J. 41, 266–273 (2008).

Anderson, M. J. & Whitcomb, P. J. RSM Simplified: Optimizing Processes Using Response Surface Methods for Design of Experiments (Productivity, 2016).

Saberi, B. et al. Mechanical and physical properties of pea starch edible films in the presence of glycerol. J. Food Process. Preserv. 40, 1339–1351 (2016).

Kaur, R. & Yadav, N. Biodegradable polymeric film for food packaging. J. Appl. Packaging Res. 11, 21–35 (2019).

Ginting, M. H. S. et al. Utilization of avocado seeds as bioplastic films filler Chitosan and ethylene glycol plasticizer. Asian J. Chem. 30, 1569–1573 (2018).

Ahmad, M. et al. Optical and thermo-mechanical properties of composite films based on fish gelatin/rice flour fabricated by casting technique. Prog Org. Coat. 84, 115–127 (2015).

Chambi, H. N. M. & Grosso, C. R. F. Mechanical and water vapor permeability properties of biodegradables films based on methylcellulose, glucomannan, pectin and gelatin. Ciência E Tecnologia De Aliment. 31, 739–746 (2011).

Vargas, C. G., Costa, T. M. H., de Rios, A., Flôres, S. H. & O. & Comparative study on the properties of films based on red rice (Oryza glaberrima) flour and starch. Food Hydrocoll. 65, 96–106 (2017).

Sudheesh, C., Sunooj, K. V., George, J., Kumar, S. & Sajeevkumar, V. A. Physico-chemical, morphological, pasting and thermal properties of stem flour and starch isolated from Kithul palm (Caryota urens) grown in Valley of Western Ghats of India. J. Food Meas. Charact. 13, 1020–1030 (2019).

Sharma, V. & Bhardwaj, A. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) in food quality evaluation. in Evaluation Technologies for Food Quality 743–761 (Elsevier, (2019).

Huang, W. et al. Strong and rapidly self-healing hydrogels: potential hemostatic materials. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 5, 2813–2822 (2016).

Lim, D. B. K. & Gong, H. Highly stretchable and transparent films based on cellulose. Carbohydr. Polym. 201, 446–453 (2018).

Macena, J. F. F., de Souza, J. C. A., Camilloto, G. P. & Cruz, R. S. Physico-chemical, morphological and technological properties of the avocado (Persea Americana Mill. cv. Hass) seed starch. Ciência E Agrotecnologia 44, (2020).

Bahru, T. B., Tadele, Z. H. & Ajebe, E. G. A review on avocado seed: functionality, composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Chem. Sci. Int. J. 27, 1–10 (2019).

de Souza, J. C. A., Macena, J. F. F., Andrade, I. H. P., Camilloto, G. P. & Cruz, R. S. Functional characterization of Mango seed starch (Mangifera indica l). Res. Soc. Dev. 10, e30310310118–e30310310118 (2021).

Zhang, W. et al. Mechanochemical activation of cellulose and its thermoplastic Polyvinyl alcohol ecocomposites with enhanced physicochemical properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 83, 257–263 (2011).

Liu, F. et al. Study of combined effects of glycerol and transglutaminase on properties of gelatin films. Food Hydrocoll. 65, 1–9 (2017).

Ilyas, R. A., Sapuan, S. M., Ishak, M. R. & Zainudin, E. S. Development and characterization of sugar palm nanocrystalline cellulose reinforced sugar palm starch bionanocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 202, 186–202 (2018).

Harsojuwono, B. A., Arnata, I. W. & Mulyani, S. Biodegradable plastic characteristics of cassava starch modified in variations temperature and drying time. J. Chem. Process. Eng. Res. 49, 1–5 (2017).

Muñoz-Gimena, P. F. et al. Avocado seed starch-Based films reinforced with starch nanocrystals. Polym. (Basel). 16, 2868 (2024).

Tarique, J., Sapuan, S. M. & Khalina, A. Effect of glycerol plasticizer loading on the physical, mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of Arrowroot (Maranta arundinacea) starch biopolymers. Sci. Rep. 11, 13900 (2021).

Kusmono, K., Wildan, M. W. & Lubis, F. I. Fabrication and characterization of Chitosan/Cellulose Nanocrystal/Glycerol Bio-Composite films. Polym. (Basel). 13, 1096 (2021).

Martins, I. M. G. et al. New biocomposites based on thermoplastic starch and bacterial cellulose. Compos. Sci. Technol. 69, 2163–2168 (2009).

Xiao, Y., Liu, Y., Kang, S. & Xu, H. Insight into the formation mechanism of soy protein isolate films improved by cellulose nanocrystals. Food Chem. 359, 129971 (2021).

Orts, W. J. et al. Application of cellulose microfibrils in polymer nanocomposites. J. Polym. Environ. 13, 301–306 (2005).

Tai, N. L., Adhikari, R., Shanks, R. & Adhikari, B. Aerobic biodegradation of starch–polyurethane flexible films under soil burial condition: changes in physical structure and chemical composition. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation. 145, 104793 (2019).

Fernandez-Saiz, P., Lagaron, J. M., Hernandez-Muñoz, P. & Ocio, M. J. Characterization of antimicrobial properties on the growth of S. aureus of novel renewable blends of gliadins and Chitosan of interest in food packaging and coating applications. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 124, 13–20 (2008).

Lubis, M., Harahap, M. B., Ginting, M. H. S., Sartika, M. & Azmi, H. Production of bioplastic from avocado seed starch reinforced with microcrystalline cellulose from sugar palm fibers. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 13, 381–393 (2018).

Maulida, S. M. & Tarigan, P. Production of starch based bioplastic from cassava Peel reinforced with microcrystalline celllulose avicel PH101 using sorbitol as plasticizer. in J Phys. Conf. Ser 710 (2016).

Ibrahim, M. I. J., Sapuan, S. M., Zainudin, E. S. & Zuhri, M. Y. M. Physical, thermal, morphological, and tensile properties of cornstarch-based films as affected by different plasticizers. Int. J. Food Prop. 22, 925–941 (2019).

Marichelvam, M. K., Jawaid, M. & Asim, M. Corn and rice starch-based bio-plastics as alternative packaging materials. Fibers 7, 1–14 (2019).

Chen, P., Xie, F., Tang, F. & McNally, T. Influence of plasticiser type and nanoclay on the properties of chitosan-based materials. Eur. Polym. J. 144, 110225 (2021).

Tarique, J., Sapuan, S. M. & Khalina, A. Effect of glycerol plasticizer loading on the physical, mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of Arrowroot (Maranta arundinacea) starch biopolymers. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–17 (2021).

Wilpiszewska, K. & Czech, Z. Citric acid modified potato starch films containing microcrystalline cellulose reinforcement–properties and application. Starch-Stärke 66, 660–667 (2014).

de Crizel, M., Costa, T. H. & de Oliveira Rios, T. M. Hickmann Flôres, S. Valorization of food-grade industrial waste in the obtaining active biodegradable films for packaging. Ind. Crops Prod. 87, 218–228 (2016).

Luchese, C. L., Spada, J. C. & Tessaro, I. C. Starch content affects physicochemical properties of corn and cassava starch-based films. Ind. Crops Prod. 109, 619–626 (2017).

Deepa, B. et al. Biodegradable nanocomposite films based on sodium alginate and cellulose nanofibrils. Materials 9, 50 (2016).

Khan, A. et al. Mechanical and barrier properties of nanocrystalline cellulose reinforced Chitosan based nanocomposite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 90, 1601–1608 (2012).

Dasan, Y. K., Bhat, A. H. & Ahmad, F. Polymer blend of PLA/PHBV based bionanocomposites reinforced with nanocrystalline cellulose for potential application as packaging material. Carbohydr. Polym. 157, 1323–1332 (2017).

de Souza, C. et al. Effect of the glycerol and lignin extracted from Piassava fiber in cassava and corn starch films. Mater. Res. 18, 260–264 (2015).

Farooq, M., Zou, T., Riviere, G., Sipponen, M. H. & Österberg, M. Strong, ductile, and waterproof cellulose nanofibril composite films with colloidal lignin particles. Biomacromolecules 20, 693–704 (2018).

Moo-Tun, N. M., Iñiguez-Covarrubias, G. & Valadez-Gonzalez, A. Assessing the effect of PLA, cellulose microfibers and CaCO3 on the properties of starch-based foams using a factorial design. Polym. Test. 86, 106482 (2020).

Sanyang, M. L., Sapuan, S. M., Jawaid, M., Ishak, M. R. & Sahari, J. Effect of plasticizer type and concentration on physical properties of biodegradable films based on sugar palm (Arenga pinnata) starch for food packaging. J. Food Sci. Technol. 53, 326–336 (2016).

Pelissari, F. M., Andrade-Mahecha, M. M., Amaral Sobral, P. J. & Menegalli, F. C. do Nanocomposites based on banana starch reinforced with cellulose nanofibers isolated from banana peels. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 505, 154–167 (2017).

Chen, F. & Chi, C. Development of pullulan/carboxylated cellulose nanocrystal/tea polyphenol Bionanocomposite films for active food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 186, 405–413 (2021).

Galus, S. & Kadzińska, J. Moisture sensitivity, optical, mechanical and structural properties of Whey protein-based edible films incorporated with rapeseed oil. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 54, 78–89 (2016).

Nordin, N., Othman, S. H., Rashid, S. A. & Basha, R. K. Effects of glycerol and thymol on physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of corn starch films. Food Hydrocoll. 106, 105884 (2020).

Admase, A. T., Sendekie, Z. B. & Alene, A. N. Biodegradable film from Mango seed kernel starch using pottery clay as filler. J. Polym. Environ. 1–16 (2022).

Beigmohammadi, F., Barzoki, Z. M. & Shabanian, M. Rye flour and cellulose reinforced starch biocomposite: A green approach to improve water vapor permeability and mechanical properties. Starch-Stärke 72, 1900169 (2020).

Moran, J. I., Vazquez, A. & Cyras, V. P. Bio-nanocomposites based on derivatized potato starch and cellulose, Preparation and characterization. J. Mater. Sci. 48, 7196–7203 (2013).

Li, W., Wang, S., Wang, W., Qin, C. & Wu, M. Facile Preparation of reactive hydrophobic cellulose nanofibril film for reducing water vapor permeability (WVP) in packaging applications. Cellulose 26, 3271–3284 (2019).

Othman, S. H. et al. Physical, Mechanical, and water vapor barrier properties of Starch/Cellulose Nanofiber/Thymol Bionanocomposite films. Polym. (Basel). 13, 4060 (2021).

Taylor, J., Zhang, K. & Wang, D. Industrial and nonfood applications. In Sorghum and Millets 393–420Elsevier, (2019).

Barrera, G. N. et al. Evaluation of the mechanical damage on wheat starch granules by SEM, ESEM, AFM and texture image analysis. Carbohydr. Polym. 98, 1449–1457 (2013).

Ashori, A. Effects of graphene on the behavior of Chitosan and starch nanocomposite films. Polym. Eng. Sci. 54, 2258–2263 (2014).

Thulasisingh, A. et al. Biodegradable packaging materials. Polymer Bulletin 1–30 (2021).

Ibrahim, M. I. J., Sapuan, S. M., Zainudin, E. S. & Zuhri, M. Y. M. Potential of using multiscale corn husk fiber as reinforcing filler in cornstarch-based biocomposites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 139, 596–604 (2019).

Zhang, Y. & Han, J. H. Plasticization of pea starch films with monosaccharides and polyols. J. Food Sci. 71, E253–E261 (2006).

Supanakorn, G., Taokaew, S. & Phisalaphong, M. Ternary composite films of natural rubber, cellulose microfiber, and carboxymethyl cellulose for excellent mechanical properties, biodegradability and chemical resistance. Cellulose 28, 8553–8566 (2021).

Domene-López, D., García-Quesada, J. C., Martin-Gullon, I. & Montalbán, M. G. Influence of starch composition and molecular weight on physicochemical properties of biodegradable films. Polym. (Basel). 11, 1084 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Preparation and performance of thermoplastic starch and microcrystalline cellulose for packaging composites: extrusion and hot pressing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 165, 2295–2302 (2020).

Boonsuk, P. et al. Modified cassava starch/poly (vinyl alcohol) blend films plasticized by glycerol: structure and properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 137, 48848 (2020).

Salleh, E., Muhamad, I. I. & Khairuddin, N. Structural characterization and physical properties of antimicrobial (AM) Starch-Based films. 428–436 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the University of Gondar and Addis Ababa Science and Technology University for facilities and technical help. Gratitude also goes to Adama Science Technology University and Bahir Dar Institute of Technology staff for XRD and DSC analyses. Addis Ababa Science and Technology University is acknowledged for laboratory and instrument access.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Negese Alemu Tassew and Tebelay Liknawa contributed to experimentation, data collection; Reddy Prasad reviewed and edited the whole article.; R. Ramesh performed the visualization, conceptualization, supervision and Meketaye Abera Endeshaw data analysis, and software.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tassew, N.A., Andualem, T.L., D M, R.P. et al. Avocado seed starch bioplastic film reinforced with enset cellulose for sustainable packaging. Sci Rep 15, 41075 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24935-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24935-3