Abstract

To evaluate the risk of fetal malformation in pregnant women with pregestational diabetes mellitus based on pre-pregnancy fasting plasma glucose (FPG) levels. This cohort study used the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) database, including 5,687 women with pre-pregnancy diabetes and FPG measurements within one year before conception. Subjects were grouped into three glycemic level categories: low (FPG < 100 mg/dL [< 5.5 mmol/L]), moderate (FPG: 100–125 mg/dL [5.6–6.9 mmol/L]), and high (FPG ≥ 126 mg/dL [≥ 7.0 mmol/L]). The low glycemic group was divided into four subgroups based on FPG levels. The relative risks of fetal malformations were calculated using multivariable analysis compared to a reference group (FPG < 84 mg/dL [< 4.7 mmol/L]). Fetal malformation rates were 10% in the low, 13.6% in the moderate, and 18.6% in the high glycemic groups (P < 0.001). Teratogenic risks were 1.3 times higher in the moderate glycemic group and 1.8 times higher in the high glycemic group compared to the reference group. The high glycemic group had 2.5 times greater risk of cardiac malformations and 3.3 times greater risk of skeletal malformations. Preconceptional FPG levels ≥ 100 mg/dL [≥ 5.5 mmol/L] in women with pregestational diabetes elevate the risk of fetal malformations, especially cardiac and skeletal malformations at FPG levels ≥ 126 mg/dL [≥ 7.0 mmol/L].

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The worldwide prevalence of diabetes or prediabetes in women of childbearing age has steadily increased in association with the growing epidemic of obesity, advancing maternal age, and improved detection due to expanded screening programs1. In Republic of Korea, it was reported that 3.5% and 7.1% of women in their respective 30 s and 40 s have diabetes, and 22.5% and 31.7% of women in their 30 s and 40 s have prediabetes2.

Pregestational diabetes mellitus (PGDM), which refers to type 1 or 2 diabetes that existed before pregnancy, is a significant risk factor for congenital malformations, particularly if blood glucose levels are not well managed during the early stages of pregnancy3,4. It has been reported that women with PGDM have an up to nine-fold greater risk for having babies with malformations, with a prevalence rate of 2.7%–18.6%, compared to the healthy population, which exhibits a prevalence rate of 2–3%5,6,7,8. Importantly, in Korea, the majority of women with PGDM are reported to have type 2 rather than type 1 diabetes, suggesting that findings based on single fasting plasma glucose measurements are likely to be more relevant to women with type 2 diabetes9.

In addition to congenital anomalies, maternal diabetes has also been associated with adverse neonatal outcomes, including abnormal fetal growth and perinatal complications10. Although the mechanism at play is not entirely understood, hyperglycemia during embryogenesis could increase oxidative stress, epigenetic changes, hypoxia, and apoptosis, contributing to DNA damage and a greater risk for congenital malformations11,12,13,14. Therefore, embryopathy associated with diabetes can affect various organ systems during fetal development, although neural tube defects and cardiovascular malformations are the most common and severe congenital anomalies associated with pregnancies in individuals with diabetes. As it is clear that better glycemic management is associated with a reduced risk of congenital anomalies4, determining the optimal threshold of glycemic control, as measured by hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level or fasting plasma glucose (FPG), for women with PGDM planning pregnancy is an ongoing area of research and debate.

The aim of our study was to evaluate both the overall and organ-specific teratogenic risks in women with PGDM based on pre-pregnancy FPG level and to investigate the target range of pre-pregnancy FPG levels to decrease those risks.

Methods

Study population

For collection of national big data, the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) service database, which covers a vast majority of the Korean population (approximately 97%) through the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS), was used. The inclusion of claims data from HIRA allowed a detailed analysis of healthcare usage patterns and medical history among the study participants. Additionally, the study incorporated information from the bi-annual National Health Screening Examination (NHSE) provided by the NHIS and the National Health Screening Program for Infants and Children (NHSP-IC). The NHSE offers insights into pregestational glucose levels, whereas the NHSP-IC, initiated in 2007, provides valuable information on physical examinations, anthropometric measurements, and developmental screening results for infants and children. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Korea University (IRB no. 2023GR0242).

Study design

The study population included women with singleton deliveries, between 2013 and 2020, who participated in the NHSE within one year prior to pregnancy and were diagnosed with any type of diabetes before pregnancy. Patients lacking detailed clinical information were excluded. Women were additionally excluded from the analysis of neonatal outcomes if their children had not participated in at least one of the seven consecutive NHSP-IC health examinations. Women diagnosed with diabetes within one year before conception were identified using the ICD-10 code (E10–14). Incident cases of type 2 diabetes, defined as pregestational diabetes diagnosed prior to pregnancy, were defined in accordance with the recommendations of the Korean Diabetes Association15.

National health screening examination before pregnancy and FPG categorization

Pre-pregnancy factors were obtained from the NHSE database, which consists of two main components: health interviews and health examinations. During the preconception health examination, the participants provided overnight fasting blood samples, from which their blood glucose concentrations were measured in the clinic. FPG levels were analyzed using automatic analyzers approved by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety of Korea and selected by the local laboratories. Pregestational FPG levels were divided into six groups, as follows: 1) FPG < 84 mg/dL [< 4.7 mmol/L] (group 1), 2) FPG 84–89 mg/dL [4.7–4.9 mmol/L] (group 2), 3) FPG 90–95 mg/dL [5.0–5.2 mmol/L] (group 3), 4) FPG 95–100 mg/dL [5.3–5.5 mmol/L] (group 4), 5) FPG 100–125 mg/dL [5.6–6.9 mmol/L] (moderate glycemic group, group 5), and 6) 1) FPG ≥ 126 mg/dL [≥ 7.0 mmol/L] (high glycemic group, group 6). Groups 1–4 were designated as the low glycemic groups, with group 1 used as the reference group in the multivariable analysis.

Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes including congenital anomalies

We used the HIRA database to identify women who had experienced hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, postpartum hemorrhage, or chronic hypertension and who underwent cesarean section during pregnancy based on ICD-10 diagnostic codes. Information regarding neonatal outcomes, such as preterm birth and neonatal sex, was obtained from the NHSP-IC database, as was that about congenital anomalies.

The primary outcomes of this study were any diagnosed neonatal congenital anomalies confirmed within 30 days after birth, based on ICD-10 diagnostic codes (Q11–Q99). Secondary outcomes were organ-specific congenital anomalies, also based on ICD-10 diagnostic codes; relevant ICD-10 codes for organ-specific anomalies were as follows: central nervous system (CNS) anomalies (Q00–Q08), face and neck anomalies (Q10–Q18), cardiovascular anomalies (Q20–Q28), respiratory anomalies (Q30–Q34), gastrointestinal anomalies (Q38–Q45), genitourinary anomalies (Q50–Q56), musculoskeletal anomalies (Q65–Q79), dermatologic anomalies (Q80–Q89), and chromosomal anomalies (Q90–Q99).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are described using mean and standard deviation (SD) and were compared using Student’s t test or analysis of variance for multiple group comparisons. Categorical variables are presented as number and percentage, and the chi-square test was used for comparisons. Study participants were stratified into six groups based on pregestational FPG levels. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to estimate the adjusted odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Adjustment variables were prespecified based on previous literature identifying maternal age, parity, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), socioeconomic status, smoking history, hypertension, and pregestational diabetes as established risk factors for adverse perinatal outcomes. These covariates were included to reduce potential confounding and to ensure that the observed associations reflected the independent contribution of FPG to congenital malformations. Analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

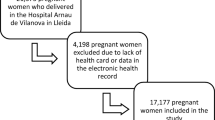

Among 41,858 women diagnosed with diabetes within one year prior to pregnancy, 9,479 women who were screened within one year before pregnancy were initially considered. After excluding 520 cases of multiple pregnancies and 3,272 cases with missing data, a total of 5,687 women was finally included in the study (Fig. 1). The patients were divided into six groups according to pre-pregnancy FPG levels; 1049 patients had FPG < 84 mg/dL [< 4.7 mmol/L] (group 1, 18.4%), 985 patients had FPG 84–89 mg/dL [4.7–4.9 mmol/L] (group 2, 17.3%), 841 patients had FPG 90–94 mg/dL [5.0–5.2 mmol/L] (group 3, 14.8%), 622 patients had FPG 95–99 mg/dL [5.3–5.5 mmol/L] (group 4, 10.9%), 1157 patients had FPG 100–126 mg/dL [5.6–6.9 mmol/L] (group 5, 20.3%), and 1033 patients had FPG ≥ 126 mg/dL [≥ 7.0 mmol/L] (group 6, 18.2%).

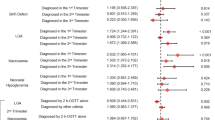

Table 1 presents maternal baseline characteristics, pregnancy outcomes, and type of congenital malformation by group according to FPG level. Across the FPG groups, maternal age and BMI tended to be higher in groups with elevated FPG levels. The proportion of nulliparous women decreased as FPG increased. In terms of pregnancy outcomes, women in groups with higher FPG levels demonstrated increased rates of cesarean section deliveries, hypertensive disease during pregnancy, and preterm delivery. In addition, higher FPG levels were linked to increased neonatal birthweight, a greater rate of low birthweight, and an increased rate of macrosomia. The rate of any congenital malformation was significantly higher in groups with elevated FPG levels, being 18.6% in the high glycemic group (group 6) and 13.6% in the moderate glycemic group (group 5), compared to approximately 10% in low glycemic groups with FPG < 100 mg/dL [< 5.5 mmol/L] (Fig. 2). When examined by specific organ system, only the circulatory system showed a significant difference in the rate of malformation among all patients with an increased frequency of malformations in groups with higher FPG levels.

The results of the regression analysis for the risk of malformation in different groups compared to those with FPG levels < 84 mg/dL [< 4.7 mmol/L] as the reference group after adjusting for maternal age, BMI, nulliparity, chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, fetal sex, and prematurity are shown in Table 2. The risk of any congenital malformation showed no significant difference between groups (groups 2–4) with FPG < 100 mg/dL [< 5.5 mmol/L] compared to the reference group (group 1). However, the risk was 1.31 times greater in the moderate glycemic group and 1.84 times higher in the high glycemic group (Fig. 2). For the circulatory system, there was no significantly different risk among groups 2–4, but the risk was increased by 1.43 times in group 5 and 2.50 times in group 6 compared to the reference group. In the musculoskeletal system, only the high glycemic group (group 6) showed a significantly increased risk, with an adjusted odds ratio of 3.29. Corresponding unadjusted odds ratios are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Discussion

Main findings

In this nationwide population-based cohort study of women with PGDM, there were no significant differences in the overall or organ-specific risks of congenital anomalies among the low glycemic subgroups according to FPG level. Notably, when preconceptional FPG levels were ≥ 100 mg/dL [≥ 5.5 mmol/L] in women with PGDM, there was an elevated risk of overall fetal malformations. Especially, preconceptional FPG level ≥ 126 mg/dL [≥ 7.0 mmol/L] is associated not only with overall- but also organ-specific congenital anomalies of the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems.

Interpretation and implications

Congenital anomalies are the second-leading cause of infant mortality after prematurity, accounting for ≥ 20% of infant deaths16. It has been reported that the prevalence of major congenital anomalies in Republic of Korea, based on the NHIS database, increased from 336 per 10,000 livebirths in 2008 to 564 per 10,000 livebirths in 201417. Although the prevalence of congenital malformation can be variably affected by improvement of prenatal or postnatal diagnosis, parental age; folic acid supplementation; and maternal illnesses and factors like maternal diabetes, infection, obesity, drug exposure, smoking, drinking alcohol, environmental exposure, multiple pregnancies, and other maternal sociodemographic characteristics have also been reported to be risk factors17,18,19,20,21,22. In this study, the low glycemic group had an about 10% overall rate of fetal malformations, while the moderate glycemic group had a 13.6% overall rate, and high glycemic group had an 18.6% overall rate of fetal malformations. As expected, the risk of congenital malformations in women with PGDM in this study was considerably higher than the 2%–4% background risk of congenital anomalies in the general population23,24,25. Our findings suggest that PGDM is a risk factor for congenital anomalies, and high levels of FPG before conception are associated with increased risk. In addition, the frequency of cardiovascular malformation was 5.6%, and the risk of cardiovascular malformation in the high glycemic group was 2.5 times greater than that of the group with FPG levels < 84 mg/dL [< 4.7 mmol/L]. Consistent with our findings, cardiovascular malformations have been reported to account for 3%–9% of pregnancies in individuals with diabetes, which is a rate approximately 2.5–10 times greater than that in pregnancies in individuals without diabetes26. Because the incidence of cardiovascular malformation in the high glycemic group was 11.8% in this study, a detailed antenatal cardiac evaluation in the first and the second trimesters may be required in women with PGDM who have elevated FPG levels. In addition, we showed that the incidence of skeletal malformation in the diabetes population in the current study was 1%, which is greater than in that in the normal population (0.01%–0.1%)4,27,28. A recent systematic review also reported a significant association between maternal diabetes and skeletal malformation, with a 1.9% (range: 0.07%–5.89%) incidence of skeletal malformation in those with PGDM29. In the present study, women in the high glycemic group had a 3.3-fold higher risk of skeletal malformations compared with those with FPG levels < 84 mg/dL [< 4.7 mmol/L]. Although the pathophysiology is not clear, maternal hyperglycemia before and during critical periods in early pregnancy may lead to changes in gene expression, resulting in mesodermal damage and a wide variety of skeletal malformations30. Our findings implicate the importance of preconceptional care for women with PGDM to reduce or mitigate risks for congenital anomalies in their offspring.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include its population-based, large-scale sample derived from national databases, which enabled us to assess associations between FPG categories and subgroups and both overall and organ-specific malformations without the dilution of risk estimates. The current study was a new attempt to investigate the impact of pregestational FPG levels on congenital malformations of newborns by categorizing FPG levels into various ranges. We used FPG rather than postprandial glucose or HbA1c as a primary measure of glycemia because it is used in many other population-based studies31,32. It may be limitation that we could not compare levels of glycemic control between FPG and HbA1c because the data from NHSE do not include HbA1c. However, by grouping FPG into ranges and examining the relative odds ratios, this study provides valuable clinical insights into the effects of glycemic control.

This study also has several limitations. Data on induced abortions or miscarriages before 20 weeks` gestation or stillbirth/termination were not included in this study because our mother–newborn linked dataset was limited to live births. Following improved prenatal early detection of malformations in Republic of Korea, the proportion of fetuses affected by a congenital anomaly that are subsequently aborted might have increased. However, elective abortion or termination is illegal in Republic of Korea, and information about congenital anomalies in abortions or terminations was not available in our national database. Our current study did not distinguish the degree of severity of anomalies, including both major and minor malformations. In addition, we could not exclude the chances of underestimation of events resulting from incorrect or insufficient diagnostic code input. Moreover, the difficulty in classifying subtypes of DM hindered distinction between type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and we were unable to obtain information regarding the use of medication. In addition, the exact timing of FPG measurement in relation to conception could not be determined, as only the most recent health screening result within one year prior to pregnancy was available. This may have limited the precision of our assessment of preconceptional glycemic status. Last, considering the retrospective nature of this study, well-designed prospective studies are needed to address these limitations.

In this study, we categorized pre-pregnancy FPG levels into clinically meaningful groups based on thresholds suggested in previous literature. This categorical approach was chosen a priori to facilitate clinical interpretation and to align with established practices in diabetes and obstetric research. While this method provides straightforward applicability for preconception counseling, we acknowledge that treating FPG as a continuous variable, particularly to visualize risk trends, and applying methods such as ROC curve analysis, Youden’s index, or minimum p-value approaches could yield more precise identification of optimal cutoff values. Future large-scale studies incorporating such analytic techniques will be valuable to further refine the predictive utility of FPG for congenital malformations.

Preconceptional care for glycemic control in women with PGDM can improve pregnancy outcomes, including congenital malformation in offspring33,34. However, this study is the first to suggest an optimal range of pre-pregnancy FPG levels to decrease the risk of congenital malformation as well as the high risk of cardiovascular and musculoskeletal anomalies in women with PGDM.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that suboptimal preconception FPG control in women with PGDM is associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations, especially cardiovascular and musculoskeletal malformations. This national population-based cohort study demonstrates that maintenance of FPG levels < 100 mg/dL [< 5.5 mmol/L] prior to pregnancy can minimize the risk of congenital malformation in the offspring of women with PGDM. Fetal echocardiography with detailed fetal anatomic evaluation will be strongly required during antenatal care, especially when the pre-pregnancy FPG level is ≥ 126 mg/dL [≥ 7.0 mmol/L].

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in the current study are not publicly available due to the nature of ethical restriction. All anonymized data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its additional files on reasonable request.

References

Cho, N. H. et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 138, 271–281 (2018).

Bae, J. H. et al. Diabetes fact sheet in Korea 2021. Diabetes Metab. J. 46, 417–426 (2022).

Temple, R. et al. Association between outcome of pregnancy and glycaemic control in early pregnancy in type 1 diabetes: population based study. BMJ 325, 1275–1276 (2002).

Gabbay-Benziv, R., Reece, E. A., Wang, F. & Yang, P. Birth defects in pregestational diabetes: Defect range, glycemic threshold and pathogenesis. World J. Diabetes 6, 481–488 (2015).

Galindo, A., Burguillo, A. G., Azriel, S. & de la Fuente, P. Outcome of fetuses in women with pregestational diabetes mellitus. J. Perinat. Med. 34(4), 323–331 (2006).

Wender-Ożegowska, E. et al. Threshold values of maternal blood glucose in early diabetic pregnancy-prediction of fetal malformations. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 84, 17–25 (2005).

Wren, C., Birrell, G. & Hawthorne, G. Cardiovascular malformations in infants of diabetic mothers. Heart 89, 1217–1220 (2003).

Reece, E. A. Diabetes-induced birth defects: what do we know? What can we do?. Curr. Diab. Rep. 12, 24–32 (2012).

Kim, H.-S. et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in Korean women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. J. 39, 316–320 (2015).

Heo, A., Chung, J., Lee, S. & Cho, H. Fetal biometry measurements in diabetic pregnant women and neonatal outcomes. Obstetrics Gynecol. Sci. 68, 69–78 (2024).

Weng, H., Li, X., Reece, E. A. & Yang, P. SOD1 suppresses maternal hyperglycemia-increased iNOS expression and consequent nitrosative stress in diabetic embryopathy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 206(448), e441-447 (2012).

Ornoy, A., Reece, E. A., Pavlinkova, G., Kappen, C. & Miller, R. K. Effect of maternal diabetes on the embryo, fetus, and children: congenital anomalies, genetic and epigenetic changes and developmental outcomes. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 105, 53–72 (2015).

Wu, Y. et al. Association of maternal prepregnancy diabetes and gestational diabetes mellitus with congenital anomalies of the newborn. Diabetes Care 43, 2983–2990 (2020).

Dong, M.-Z. et al. Diabetic uterine environment leads to disorders in metabolism of offspring. Front Cell Dev Biol 9, 706879 (2021).

Ko, S. H. et al. Past and current status of adult type 2 diabetes mellitus management in Korea: A national health insurance service database analysis. Diabetes Metab. J. 42, 93–100 (2018).

Almli, L. M. et al. Association between infant mortality attributable to birth defects and payment source for delivery—United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 66, 84–87 (2017).

Ko, J.-K., Lamichhane, D. K., Kim, H.-C. & Leem, J.-H. Trends in the prevalences of selected birth defects in Korea (2008–2014). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 923 (2018).

Jenkins, K. J. et al. Noninherited risk factors and congenital cardiovascular defects: current knowledge: A scientific statement from the American heart association council on cardiovascular disease in the young: endorsed by the American academy of pediatrics. Circulation 115, 2995–3014 (2007).

Leirgul, E. et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart defects in Norway 1994–2009: A nationwide study. Am. Heart J. 168, 956–964 (2014).

Choodinatha, H. K. et al. Cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Sci 66, 463–476 (2023).

Shin, J. E. et al. Congenital Anomalies in Multiple Pregnancy: A Literature Review. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 79, 167–175 (2024).

You, S. J. et al. The influence of advanced maternal age on congenital malformations, short-and long-term outcomes in offspring of nulligravida: a Korean National Cohort Study over 15 years. Obstetrics & Gynecology Science 67, 380–392 (2024).

Greene, M. F., Hare, J. W., Cloherty, J. P., Benacerraf, B. R. & Soeldner, J. S. First-trimester hemoglobin A1 and risk for major malformation and spontaneous abortion in diabetic pregnancy. Teratology 39, 225–231 (1989).

Holmes, L. B. Current concepts in genetics. Congenital Malformations. N. Engl. J. Med. 295, 204–207 (1976).

Ylinen, K., Aula, P., Stenman, U. H., Kesäniemi-Kuokkanen, T. & Teramo, K. Risk of minor and major fetal malformations in diabetics with high haemoglobin A1c values in early pregnancy. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed) 289, 345–346 (1984).

Al-Biltagi, M., El Razaky, O. & El Amrousy, D. Cardiac changes in infants of diabetic mothers. World J. Diabetes 12, 1233–1247 (2021).

Tinker, S. C. et al. Specific birth defects in pregnancies of women with diabetes: National birth defects prevention study, 1997–2011. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 222(176), e171-176.e111 (2020).

Zhao, E., Zhang, Y., Zeng, X. & Liu, B. Association between maternal diabetes mellitus and the risk of congenital malformations: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Drug Discov. Ther. 9, 274–281 (2015).

Shah, K. & Shah, H. A systematic review of maternal diabetes and congenital skeletal malformation. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 62, 113–122 (2022).

Eriksson, U. J. et al. Pathogenesis of diabetes-induced congenital malformations. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 105, 53–84 (2000).

Danaei, G. et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2· 7 million participants. Lancet 378, 31–40 (2011).

Wei, Y. et al. Preconception diabetes mellitus and adverse pregnancy outcomes in over 6.4 million women: a population-based cohort study in China. PLoS Med. 16, e1002926 (2019).

Davidson, A. J. F. et al. Association of improved periconception hemoglobin A1c with pregnancy outcomes in women with diabetes. JAMA Netw Open 3, e2030207 (2020).

Wahabi, H. A. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of pre-pregnancy care for women with diabetes for improving maternal and perinatal outcomes. PLoS ONE 15, e0237571 (2020).

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center (PACEN) funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number : RS-2023-KH137595). The authors wish to acknowledge the financial support of the Catholic Medical Center Research Foundation made in the program year of 2025.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Subeen Hong: Investigation, Writing—Original Draft Kyung A Lee: : Investigation, Writing—Original Draft Young Mi Jung: Methodology, Resources Heechul Jeong: Formal anlaysis Ji-Hee Sung: Validation, Methodology Hyun-Joo Seol: Investigation, Validation Won Joon Seong: Investigation, Methodology Soo Ran Choi: Investigation, Methodology Joon Ho Lee: Validation, Methodology Seung Cheol Kim: Validation, Methodology Sae-Kyoung Choi: Validation, Methodology Ji Young Kwon: Validation, Methodology Hyun Soo Park: Validation, Methodology Hyun Sun Ko: Conceptualization, Writing—Review & Editing, Funding acquisition Geum Joon Cho: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was also approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korean University Guro Hospital (No. 2023GR0152). All methods were performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Anonymized and deidentifed information for participants was used for analysis, so the requirement for informed consent or parental permission was waived by the Institutional Review Board of the Korean University Guro Hospital.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, S., Lee, K.A., Jung, Y.M. et al. Fetal malformations in women with pregestational diabetes mellitus based on pre-pregnancy fasting plasma glucose levels. Sci Rep 15, 41128 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24954-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24954-0