Abstract

Growing environmental concerns have intensified research into sustainable construction materials, such as natural fiber-reinforced concrete. Among these, lightweight foamed concrete (LFC) stands out for its reduced material consumption, improved thermal insulation, and lower environmental footprint. The integration of natural fibers, such as sugarcane bagasse fiber (SBF), into LFC has the potential to further enhance its performance. This study investigates the influence of varying SBF weight fractions (0%, 1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, and 5%) on the physical, mechanical, and durability properties of LFC with a target density of 1000 kg/m3. The primary objective was to determine the optimal SBF content for achieving superior material characteristics. Experimental results revealed that the inclusion of 4% SBF provided the best overall performance, improving compressive strength by 53%, increasing ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) by 17%, and reducing drying shrinkage by 58% compared to the control mix. Additionally, slump flow decreased progressively with higher fiber content, indicating enhanced cohesion. Water absorption and porosity were significantly reduced with increasing SBF, with the 5% mix showing up to a 19% decrease in water absorption. Thermal conductivity also declined slightly, suggesting improved insulation properties. Microstructural analysis confirmed better fiber-matrix bonding at the optimal fiber content, contributing to the observed improvements in performance. This study offers valuable insights into the mechanical, thermal, and durability characteristics of LFC-SBF composites, highlighting their potential as sustainable construction materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There has been a growing development in recent years towards using lightweight foamed concrete (LFC) in the building of infrastructure and the industrialized building system sector1. LFC has the possibility to be a viable alternative to conventional normal-strength concrete since it minimizes dead loads, promotes energy conservation, and lessens production costs2. LFC is a lightweight compound composed of a filler, binder, clean water and surfactant. It is a highly air-entrained system with a cellular microstructure and has conventionally observed physical and mechanical properties3. The air that is introduced into the matrix of the material during the process of combining the cement slurry with a suitably prepared foam gives the material its lightweight qualities4. Using compressed air, a solution containing water and a foaming ingredient is expanded to form foam. In contrast to normal-weight concrete, LFC possesses a number of distinctive properties that are a result of the presence of air bubbles. These properties, which include low density, excellent thermal insulation properties and good acoustic absorption capability, make LFC an especially desirable material to be employed in the building sector5.

Sugarcane is the most widely cultivated crop in the world6. Each year, the subcontinent produces over 300 million tonnes of sugarcane, which eventually results in the production of about 9 million tonnes of sugarcane bagasse7. In sugar mill boilers, sugarcane bagasse is the most used fuel. Bagasse fiber’s cheap cost, low density, and good mechanical qualities make it an attractive choice for value-added applications such as plastic composite reinforcement8. Sugarcane bagasse is an enormously agricultural byproduct all over the world. In 2024, sugarcane cultivation in Malaysia produced about 215,500 tonnes of bagasse from 750,000 tonnes of sugarcane9. If not handled correctly, this large amount of bagasse might cause environmental problems because it has a lot of moisture in it and could catch fire on its own. But if used correctly, bagasse may be turned into useful things like biofuels, bioplastics, and building materials. This cuts down on waste and helps with attempts to be more environmentally friendly. Bagasse has commercial potential as a cement composite reinforcement. There are several advantages to using natural fiber as reinforcement in cement composites, some of which are related to the fiber’s mechanical and thermal properties. Other advantages include the material’s cost-effectiveness10. Sugarcane bagasse fiber (SBF) is an outstanding example of an abundantly accessible natural fiber and can be implemented in concrete to enhance the property.

LFC consists of a mortar slurry aerated by mechanical preforming, mixing foaming, or chemical aeration11. This creates an air-void system inside the mortar slurry. LFC typically has a dry density that ranges from 550 to 1850 kg/m3, compressive strength that falls below 25 N/mm2, and thermal conductivities that fall somewhere in the range of approximately 0.12–0.95 W/mK12,13. The primary function of this material is to act as a thermal insulator, and it can be used for construction purposes14. When compared to normal-strength concrete and other insulated compounds containing natural or polymeric materials, LFC usually demonstrates superior functional performance15,16. It is, however, a fact that its applications in the construction sector accounted for less than 20% of the total because of a lack of concern, non-reliability of materials, durability, and practicality of technology with regard to its use. In point of fact, the production of a stable LFC is reliant on a number of considerations17. These factors include the choice of materials and surfactant types, the use of additives (both natural and synthetic fibers), the design of the mixture, and the technology that is utilized during the manufacturing process18,19. Because the cement-based material’s properties are vulnerable to the pore regularity, the features of the pores, including their shape, size, and connectivity, are essential components. These have a direct effect on how stress is dispersed throughout the material and its permeability, which reflects its durability and mechanical properties20.

By modifying the typically fragile performance of concrete to elastic–plastic properties21, the fibers inclusion can enhance its load transfer and ductileness. This work is crucial since it may help further LFC’s structural applications. According to Flores-Johnson and Li22, the insertion of a 3% volume fraction of polyvinyl alcohol fibers in LFC of 1000 kg/m3 density had increased the tensile and compressive strengths by 558% and 85% correspondingly associated to the control sample. Additionally, they found that the existence of polyvinyl alcohol fibers in LFC plays an essential role to transform LFC’s brittle nature to a ductile state. Jones and McCarthy23 attempted to use polypropylene fibers with volume fractions of 0.25% and 0.50% to improve the properties of LFC strength of 1400 kg/m3 density. At a volume fraction of 0.50%, the compressive and flexural strengths of the LFC were respectively 52% and 58% higher than those of the control LFC. According to research by Othuman Mydin and Soleimanzadeh24, adding polypropylene fibers to LFC at volume fractions of up to 0.4% increased the LFC’s flexural strength at densities between 600 and 1400 kg/m3. As the fiber volume percentage increased from 0.2 to 0.4%, the void structure became stiffer, most notably in the regions surrounding the fibers.

In spite of the extensive research that has been conducted to evaluate the properties of natural fiber-strengthened cement-based composites, the majority of these efforts have been focused on normal-strength concrete. The effectiveness of LFCs reinforced with natural fibers is not well researched. A LFC specimen containing a volume fraction of 0.45% kenaf fiber and a density of 1250 kg/m3 was demonstrated to have an increased strength than a control LFC specimen as stated by Mahzabin et al.25. LFC reinforced with 0.2% and 0.4% coconut fiber were reported to have excellent mechanical performance according to Othuman Mydin et al.26. Natural fiber reinforcement enhanced the LFC’s tensile, compressive, flexural, and impact resistance. According to research by Liu et al.27, the mechanical characteristics and shrinkage performance of LFC were enhanced by the addition of 0.75% sisal fiber. It was observed by Amarnath and Ramachandrudu28 that the LFC tensile and compressive strengths were improved when sisal fiber was used as reinforcement. Henequen fibers were initiate to progress the properties of LFC by Flores-Johnson et al.29.

The uniqueness of this investigation resides in the innovative application of SBF as an environmentally friendly reinforcement in LFC, tackling both environmental disposal and the increase in efficiency in construction materials. Previous research has examined natural fibers in concrete; however, there has been insufficient focus on agricultural waste fibers in foamed concrete, especially on a systematic analysis of differing fiber contents. This study exclusively examines the influence of various SBF weight fractions on an extensive array of performance measures, including compressive strength, ultrasonic pulse velocity, drying shrinkage, water absorption, porosity, slump flow, and thermal behaviour. The study is also unique since it confirms its results by comparing them to established international design codes as ACI 363R, ACI 318, AS 3600, CEB-FIB, NZS 3101, IS 456, and SBC 304. This makes the findings more reliable. Also, a new empirical relationship has been created to anticipate strength behaviour based on SBF content. This will be useful for mix design in the future. The combination of performance-based analysis with environmental relevance especially in Malaysia, where sugarcane bagasse is a major agro-industrial waste makes this study a big step forward for sustainable construction techniques.

Importance of research

Sugarcane bagasse is a plentiful agricultural byproduct with considerable potential for value-added uses in construction materials. Annually, some 280 million metric tonnes of bagasse are generated globally, and inadequate management may result in environmental complications. When effectively employed, sugarcane bagasse can be transformed into valuable goods such as biofuels, bioplastics, and construction materials. The low cost, low density, and favorable mechanical properties of bagasse fiber render it an exceptional candidate for reinforcing cement composites, hence improving their mechanical and thermal characteristics. LFC, commonly utilized for its thermal insulation capabilities, has demonstrated enhanced performance relative to conventional concrete, particularly when augmented with natural fibers. Notwithstanding comprehensive studies on natural fiber reinforcing in concrete, the application of agricultural waste fibers, such as sugarcane bagasse, in LFC remains insufficiently investigated. This research vacuum offers a substantial opportunity for this study to investigate the possibility of SBF as an eco-friendly reinforcement in LFC.

Objectives of the research

This study aims to examine the impact of different weight fractions of SBF (0%, 1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, and 5%) on the physical, mechanical, and durability characteristics of LFC with a target density of 1000 kg/m3. The research seeks to identify the ideal SBF content for attaining enhanced material properties, including compressive strength, ultrasonic pulse velocity, drying shrinkage, water absorption, porosity, slump flow, and thermal conductivity. A new empirical connection will be established to forecast the strength characteristics of LFC enhanced with SBF.

Innovation and contribution

This study’s originality resides in the methodical investigation of differing SBF composition in LFC and its effects on numerous performance metrics, a topic that has not been thoroughly examined in the current literature. This research examines the unique effects of SBF in LFC, an area that has been insufficiently explored, in contrast to other studies that concentrated on natural fibers in normal-strength concrete. Furthermore, the study juxtaposes experimental outcomes with recognized worldwide design codes, so augmenting the credibility of the results. The creation of a novel empirical model to forecast the behavior of LFC-SBF composites will yield significant insights for forthcoming mix designs. This discovery is important, especially in Malaysia, where sugarcane bagasse constitutes a substantial agro-industrial waste product. The study seeks to provide sustainable construction solutions through the use of this plentiful waste material, so aiding environmental conservation and the progression of sustainable building methodologies.

Materials and methods

Materials

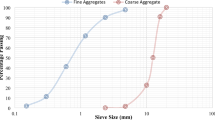

Throughout this investigation, cement designated as CEM I 52.5 R was employed to formulate all combinations in accordance with the specifications set forth in BS EN 197-130. The first setting time for standard Portland cement is 45 min. Moreover, the filler employed was fine river sand. Fine river sand was chosen due of its cohesiveness, elevated surface area, and gradation characteristics. The gradation qualities significantly influence the workability of LFC. The diminished workability of LFC results from the reduced particle size, with the extent of this effect being contingent upon the specific surface area. Additionally, fine filler enhances the compaction efficiency of LFC mixes. Figure 1 illustrates the grading curve of the river sand utilized in this study. The LFC was blended and treated with potable water, adhering to the BS-3148 requirements31. To achieve the desired foaming level, the protein surfactant Noraite PA-1 was utilized. The quantity of surfactant added to the water during the mixing procedure was one part for every thirty-four parts of water. Upon being aerated, the foam solution achieved a density of 70 kg/m3 on the density scale.

Sand grading curve in line with ASTM C33-0332.

The sugarcane bagasse is harvested and processed from a local farm. Sugarcane bagasse is the fibrous residue resulting from the extraction of juice from sugarcane. Figure 2a illustrates the acquired sugarcane bagasse. The sugarcane bagasse obtained from a local farm was subsequently truncated to a length of 80 to 90 mm. The sliced segments were further processed in a water-fed mechanical refiner. The ground stem products were subsequently cleaned and dried in the laboratory utilizing a draining machine. The processed sugarcane bagasse fiber was subsequently air-dried in the laboratory for 72 h. Figure 2b illustrates that the desiccated fiber is referred to as raw sugarcane bagasse fiber (SBF). The processed raw SBF was subsequently packaged in plastic bags and refrigerated. Table 1 illustrates the physical features of SBF, Table 2 presents its chemical composition, and Table 3 delineates its mechanical qualities.

Mix proportioning

In this laboratory investigation, six LFC mixes were prepared. The binder-filler ratio of 1:1.5 was employed for entire mixtures. The water-binder ratio was kept at 0.45. Besides, 6 varying SBF weight fractions were used explicitly, 0% (control), 1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, and 5%. The density of LFC was adjusted to be within a range of 1000 ± 20 kg/m3 for all samples by retaining the fresh density to approximately 1136 ± 20 kg/m3. Table 4 shows the mix proportion of LFC. To attain the LFC to the specified dry density of 1000 kg/m3, the foam volume in the mix had to be meticulously changed while keeping the base slurry composition the same. To make the base mix, standard Portland cement, fine sand, and water were mixed together in a set ratio of water to cement of 0.45. A protein based foaming agent was used to make a stable pre-formed foam, which we then combined with the cement-sand slurry. To get the right density, trial mixes were done where the amount of foam added to the base slurry was changed. Using the density bucket method described in ASTM C79633, we assessed the wet density of each trial mix right after mixing. Once the right amount of foam was found to consistently give a wet density of about 1030 kg/m3, taking into account drying and curing shrinkage, the dry density after 28 days stabilised close to the aim of 1000 kg/m3. This density level was designed to find a balance between workability and mechanical strength on the one hand and thermal insulation and light weight on the other.

Experimental setup

Flow table test

Slump flow was designed to find out the workability as well as the consistency of LFC mixes. Figure 3a shows the setup of flow table test. The result was derived from the vertical and horizontal dispersion diameters of the mix. The slump flow test was achieved by comparing the used 0% to 5% SBF to the slump flow test result. The static free flow test was used to determine the values for the flow table, as per ASTM C230-9734. In the static test, only static gravity load is applied to the material.

Water absorption test

The BS 1881-12235 standard was strictly adhered to establish the LFC water absorption. This standard is recognized as being the single-point absorptivity test that is both the fastest and the least expensive apparatus. Figure 3b shows the cube specimens were kept in a container filled with water. The cube LFC sample size for this water absorption test is 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm The test was performed on day 28. LFC specimens need to be dried for 72 h at 105 °C. When the LFC samples have been removed from the oven, they are allowed to cool at room temperature for 24 h in an airtight container, followed by 30 min of immersion in water. Subsequently, the water absorption is determined by calculating the percentage of the dry specimen’s mass that corresponds to the increase in mass that the specimen experienced as a result of being immersed after a period of 30 min.

Permeable porosity test

After drying out the specimens (cylinders of 100 × 50 mm), they were stuffed into a desiccator and placed under vacuum for three days as shown in Fig. 3c. A three-day oven-dried was conducted in order to determine the composition mass. As soon as the samples had cooled to room temperature, they were removed from the oven. The weight of the specimens should be established so that the oven-dray mass can be calculated, and so that the specimens may be prepared for vacuum saturation at the same time. During this time, the vacuum pumping will continue for a total of three days despite the vacuum line connection being coupled to a pressure gauge. Finally, the permeable porosity of LFC was evaluated using Eq. (1) below:

where Wb represents the saturated in water, Wd represents the oven-dry mass in air, and Ws represents the saturated surface-dry mass in air.

Ultrasonic pulse velocity test

LFC prism measuring 100mm in width, 100mm in height, and 500mm in length were subjected to a UPV test in line with BS12504-436 standard as displayed in Fig. 3d. To appraise the performance of the LFC prisms, UPV was measured in three different conditions, which were directly (Vd), indirectly (Vi), and semi-directly (Vs). At 28 days of age, it is expected that the moisture profile of the LFC along the depth will be relatively stable. Each LFC prism was quantified six times for direct, indirect, and semi-direct UPV and the average of those values is used to determine the prism’s UPV rating.

Shrinkage test

ASTM C87837 was followed during the shrinkage test. This test method measures the length changes that occur in expansive LFC when constrained as exhibited in Fig. 3e. These length changes are the result of the development of internal forces that are caused by the expansive reaction that takes place during the early stages of the hydration process of the cement. The prism sample with dimensions of 75mm × 75mm × 250mm was cast in a steel mould that consisted of a steel rod with a diameter of 4.76 mm, with steel end plates measuring 76 × 76 × 9.5 mm and being held in place by nuts. The measurements of drying shrinkage were taken on days 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, and 56 respectively. For each proportion of LFC in the mix, the results were calculated from an average of three samples.

Compressive strength test

A compression test was performed using LFC cubes sized 100 × 100 × 100mm, in accordance with BS12390-338 as displayed in Fig. 3f. Three LFC specimens were made and examined at varying curing times of 7, 28, and 56 days. Tests were performed on three FC specimens from each age of curing to establish the average compressive strength.

Flexural strength test

A rectangular prism with a dimension of 100 × 100 × 500 mm was examined in this study with regard to its flexural strength as displayed in Fig. 3g. BS12390-539 was used as the standard for the test procedures. An examination was conducted on three FC specimens that had been cured for 7, 28, and 56 days. A mean flexural strength was determined for three FC specimens at every curing age.

Splitting tensile strength test

According to BS12390-640, splitting tensile strength was tested as displayed in Fig. 3h. Cylindrical samples were used for the experiments, with a diameter of 200 mm and a length of 100 mm. LFC specimens were fabricated and tested after 7, 28 and 56 days of curing. Based on the data obtained from these three specimens at different curing stages, the average splitting tensile strength was calculated.

Modulus of elasticity test

A 28-day cure was applied to FC specimens in this study prior to measuring their Modulus of Elasicity (MoE). The specimens used in this experiment were cylindrical specimens measuring 100 mm × 200 mm in accordance with ASTM C46941. Three specimens from each curing age were examined in order to determine the average strength characteristics.

Thermal performance assessment

Using the hot guarded plate method, three parameters were measured to investigate the thermal characteristics of LFC varying mixes, namely thermal conductivity, thermal diffusivity, and specific heat capacity as displayed in Fig. 3i. ASTM C177-1942 was followed for the conduct of the test. The dimensions of the sample were 25 mm × 25 mm × 10 mm.

Scanning electron microscopy test

Several LFC specimens were analyzed using SEM to obtain high-resolution images of the surfaces and microstructures according to ISO 1670043. This allows for a thorough inspection of the surfaces of LFC samples, which is useful for spotting any defects. The 120 × magnification used in the SEM study provides enough information for viewing the surface without seriously affecting the FC specimens. A rectangular sample of 14 × 14 × 14 mm was prepared for this test.

Mercury intrusion porosimetry test

As per ASTM D4404-1844, the Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP) technique was used to assess FC pore size distribution and intrusion volume. MIP is a method for testing the pore structure of cement-based materials by measuring how much mercury gets into the pores when the pressure is regulated. In this method, a dried sample is put in a sealed chamber, and mercury is pushed into the pores little by little by using higher and higher pressures. To fill larger pores, the test starts with low pressures of about 0.003 to 0.005 MPa. It then slowly rises to very high pressures of up to 200 MPa to get into fine pores that are only a few nanometres across. To learn about the microstructural features of the material, scientists measure the amount of mercury that enters at each pressure level. This tells them the pore size distribution, overall porosity, and pore connectedness.

Results and discussion

Slump flow

Figure 4 demonstrates the slump flow behavior of LFC containing varying weight fractions of SBF. When the weight fractions of SBF were increased from 1 to 5% in the LFC mixtures, a consistent reduction in slump flow was noted. The control LFC (FC0 mix) has the highest slump flow of 253mm, while the mix with 5% SBF (FC5) gave the lowest value of 203mm. The target slump range for acceptable workability was set between 200 and 250 mm. Notably, slump flow serves as an indicator of the fresh-state workability of LFC, and the recorded values suggest a transition from moderate to low workability with increasing SBF content. As shown in Fig. 3, the slump flow of each lightweight foamed concrete (LFC) mixture exceeded 200 mm, demonstrating good self-flowing and self-leveling properties, which is consistent with findings reported by Jones and Giannakou45 However, the FC5 mix, containing the highest sugarcane bagasse fiber (SBF) content, exhibited a significant reduction in slump flow, resulting in a stiffer cementitious paste. This behavior aligns with observations by Le et al.46, who attributed decreased workability to the more angular particle shapes of SBF and its irregular morphology. The greater surface area of SBF increases inter-fiber abrasion, leading to reduced slump flow as fiber content increases, confirming trends noted in previous studies.

Density

LFC dry density varies depending on the mix compositions, including the type of cement and sand, the form of surfactant, and the presence of additives in the LFC base formulation. Anyway, the final dry density of LFC should be monitored within ± 50 kg/m3 from its target density. Figure 5 illustrates the effect of varying SBF weight fractions on the dry density of LFC mixtures. In general, the dry density of LFC recorded a slight increase with the rise in SBF weight fraction (from 1 to 5%) and the increase of curing period (from day 7 to 56). On day 28, the LFC mixture that included a 5% fraction of SBF weight had the highest dry density of 1027 kg/m3, while the conventional LFC mixture had the lowest density of 1015 kg/m3. As far as curing age is concerned, the density of LFC with the count of a 2% weight fraction of SBF on day 7 was 1006 kg/m3, and it expanded to 1020 kg/m3 on day 28 and achieved a density of 1024 kg/m3. Nevertheless, the dry density on day 56 was still within the recommended value. The differences between the target density and final density were ± 18, ± 21, ± 24, ± 27, ± 29 and ± 34 kg/m3 for control, 1%, 2%, 3%, 4% and 5% SBF. The observed increase in density can be attributed to the higher specific gravity of sugarcane bagasse fiber (SBF) within the cementitious matrix. This is consistent with the findings of Jagadesh et al.47 who reported that natural fibers act as fillers in lightweight foamed concrete (LFC), reducing porosity and void content. The filler effect promotes matrix densification, leading to a notable increase in the overall density of the composite material.

Water absorption

The effect of varying SBF weight fractions on the water absorption capacity of LFC is shown in Fig. 6. The presence of SBF, in general, leads to a significant reduction in water absorption by LFC. The water absorption capacity of LFC gradually decreases as the SBF content increases from 1 to 5%. The minimal water absorption was recorded for the LFC mixture with the existence of a 5% weight fraction of SBF, which was 20.4%. Compared to the control LFC (25.3%), a reduction of 19.4% in water absorption capacity was attained on day 28. A higher concentration of SBF resulted in smaller capillary pores, which decreased the rate of LFC water absorption. The increased content of fibers limited water infiltration into the cement based materials by reducing pore size and volume, a behavior also observed by Rawat et al.48. During drying, sugarcane bagasse fibers (SBF) lost moisture and reverted to their original dimensions, helping maintain the integrity of the pore structure. Higher fiber content contributed to the refinement of pore size, likely due to the formation of additional calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel within the cement matrix. Furthermore, the hydrophobic nature of lignin, a major component of SBF, protects the fibers from hydrothermal degradation, as noted in previous studies. Consequently, LFC composites containing SBF with higher lignin content tend to exhibit lower water absorption values, since lignin acts as a natural barrier that limits moisture ingress and mitigates deterioration.

Porosity

The influence of varying weight fractions of SBF on the porosity of LFC mixtures is indicated in Fig. 7. Generally, it can be seen from Fig. 6 that with the rise in the weight fraction of SBF in LFC, the LFC porosity reduced progressively. The findings reveal that the lowest porosity (50.3%) was achieved with a 5% SBF weight fraction in LFC, while the greatest porosity (53.8%) was attained in the control LFC sample on day 28. A larger volume percentage of SBF in LFC helps to bridge the matrix, lowering LFC porosity. The observed decrease in porosity percentage with increasing sugarcane bagasse fiber (SBF) content may be attributed to reduced water absorption and the void-filling effect provided by SBF within the lightweight foamed concrete (LFC) matrix. This aligns with findings by Jagadesh et al.48, who emphasized that the compatibility between natural fibers and the cementitious matrix is a key factor governing moisture absorption and porosity characteristics. As a result, SBF-reinforced LFC composites demonstrate enhanced resistance to porosity and water absorption, improving their overall durability.

Additionally, the decrease in porosity and water absorption with the addition of SBF to LFC primarily happens because of both the chemical and physical interactions between the SBF and the matrix of cement. SBF has huge amounts of surface area and a porous structure within that permits it to immerse up and keep water while they are being mixed. Throughout the curing process, the water that was absorbed is slowly released. This helps with internal restoration and makes the hydration process more thorough and even. Further hydration renders the microscopic structure denser as well as refined, with lesser unhydrated cement fragments and unconnected pores. SBF also works as a micro-filler, filling up empty areas in the LFC matrix that would otherwise stay as capillary pores. The fibrous network also fills in small crevices and helps keep things from shrinking, which stops more pores from forming as the material dries. The more fiber there is, the more linked and denser the matrix becomes. This makes the pore structure less continuous, which stops water from getting in. Also, the SBF that are bound together and interacting with the cement gel can help pack the particles more tightly and stop free water from moving, which lowers the water absorption capacity even more.

Figure 8 demonstrates the association between water absorption and permeable porosity of LFC with varying SBF weight fractions. There is a solid straight correlation between porosity and water absorption capacity with an R2 (coefficient of determination) value of 0.86. When the water absorption of LFC decreases, the porosity reduces as well.

Water molecules have an influence on the structure and characteristics of the SBF, LFC matrix, and the contact between them. Water intake may also impact matrix structure via mechanisms such as chain reorientation and shrinking. Because of its hydrophobic nature, SBF leads to improved compatibilization between SBF and matrix, resulting in improved bonding and interface adhesion4. This led to reduced porosity and water absorption capacity when the weight fractions increased from 1 to 5%. Vallejos et al.49 reported that the addition of the SBF decreases water absorption in concrete.

Drying shrinkage

Figure 9 depicts the results of LFC shrinkage reinforced with fluctuating SBF weight fractions. The drying shrinkage of LFC utterly follows three definite forms. Initially, instant shrinkage occurs soon after the start of drying and the tendency persists up to 7 days of the test. Then, shrinkage increases progressively over the 28 days drying period, depending on LFC mixtures and weight fractions of SBF. Lastly, the rate of shrinkage turns out to be stable for the mixtures in the presence of SBF, and very little to no shrinkage occurs even with an increment in drying age. LFC with a 4% weight fraction of SBF gave the lowest drying shrinkage compared to the other amount of SBF in LFC. The percentage of improvement was approximately 58% from the control specimen. It should be pointed out that the control LFC specimen still experienced further drying shrinkage even after 28 days of the test. The presence of SBF in LFC plays a vital role in mitigating shrinkage. Consistent with water absorption results, the rate of water absorption decreases as the SBF content increases, which correlates with reduced drying shrinkage. This is because SBF, with its lower absorption capacity, helps retain chemically bound and free water within the matrix, gradually releasing it over time and thereby limiting volume changes during drying. However, as noted by Raj et al.50, higher natural fiber content can also lead to increased drying shrinkage due to the fibers’ water retention ability. The combined influence of drying age and fiber characteristics on shrinkage behavior has been further discussed by Amran et al.1. Additionally, SBF acts as a micro-crack inhibitor within the foam mix, preventing crack propagation and widening, which contributes to shrinkage reduction, as reported by Roslan et al.51.

Ultrasonic pulse velocity

As shown in Fig. 10, various SBF weight fractions have a significant impact of UPV on LFC. The UPV tends to increase as the SBF in the LFC increases. As compared to the control mixes that had the lowest readings of 2122 m/s (direct method), 2053 m/s (semi-direct method), and 2002 m/s (indirect method), 4% SBF resulted in the highest UPV readings of 2475 m/s (direct method), 2390 m/s (semi-direct method), and 2333 m/s (indirect method). UPV measurements are affected by the presence of voids and heterogeneity in LFC. Pulses will move at a faster speed when the density of the LFC increases. Furthermore, if deformation of the LFC is detected, the time trip will be minimized.

Figures 11, 12 and 13 reveal the correlations between direct and indirect UPV, direct and semi-direct UPV, and indirect and semi-direct UPV. The basic regression model was used to detect the aforementioned associations since it is straightforward to calculate. The R2 values of 0.98 (direct–indirect), 0.98 (direct-semidirect) and 0.96 (indirect-semidirect) clearly reveal that the best-fit lines in Figs. 11, 12 and 13 have a strong connection. Direct UPV has an average value that is 3% and 6% greater than semi-indirect UPV and indirect UPV, respectively, for the control LFC specimen. The semidirect UPV of the control LFC is 2.6% more than the indirect UPV. A weak bond between the cement matrix and filler may develop beneath sand aggregate particles when fiber and cementitious materials segregate within the lightweight foamed concrete (LFC). Due to gravity, horizontal planes of weakness often form in the cast LFC, leading to a higher void ratio along the horizontal plane compared to the vertical plane. This explains why indirect ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) measurements tend to be higher in the vertical direction than horizontally. Similar influences of porosity characteristics on UPV were reported by Liu et al.52, who confirmed strong correlations between UPV and pore radius as well as pore distribution, regardless of other major mix components. Additionally, Gong and Zhang53 investigated the impact of pozzolanic powder dosage and type on UPV, noting that increases in pore size or overall porosity typically lead to corresponding increases in UPV values in LFC.

Modulus of elasticity

An increase in the SBF content to 1%, 2%, 3%, and 4% resulted in a corresponding rise in the modulus of elasticity (MoE) by 7.77%, 16.24%, 30.65%, and 53.05%, respectively, compared to the control mix (FC0), as shown in Fig. 14. This trend demonstrates the beneficial effect of SBF in enhancing the stiffness of LFC up to an optimum level. However, with a further increase to 5% SBF, the MoE decreased by 1.53% compared to the control, indicating that excessive SBF content negatively impacts the elastic behavior of the mix.

The MoE for SBF-reinforced LFC ranged from 1.09 GPa to 1.55 GPa for SBF contents between 1 and 4%, with a peak observed at 4%. The decline at 5% can be attributed to reduced workability, SBF agglomeration, and increased porosity, which disrupt the matrix continuity and reduce the material’s ability to resist deformation under stress. These observations are consistent with findings by Amran et al.54, who noted that a reduction in LFC density—caused by increased SBF content or improper compaction leads to a corresponding decrease in both compressive strength and MoE. Similarly, Zhou et al.55 reported that both MoE and compressive strength are highly sensitive to porosity and density in lightweight concrete systems.

Furthermore, Hernandez-Olivares et al.56 demonstrated that the inclusion of short SBF can significantly enhance MoE by improving crack-bridging capacity and resisting deformation. However, beyond an optimal threshold, excessive SBF content contributes to weak zones, higher void content, and uneven stress distribution, all of which reduce stiffness.

Additionally, due to the inherently higher porosity of LFC, the stress–strain curve tends to exhibit sharper curvature near the failure point compared to normal concrete, indicating a more brittle failure mode. This is primarily due to the lower solid content in LFC, which reduces its energy absorption capacity and structural ductility. In related studies, the inclusion of other fibers such as basalt at an optimum dosage of 4% also showed improvement in MoE due to enhanced resistance to deformation under external stress.

Compressive strength

The impact of SBF dosage on the compressive strength with respect to the different curing ages was noted in Fig. 15. For the 7th day of the curing period, the SBF dosage was 1%, 2%, 3% and 4% in LFC; there is a rise in the compressive strength as 1.44%, 5.89%, 31.35%, and 58.43% compared to control concrete was noted. After that, there was a reduction in the compressive strength of 12.53% for 5% SBF dosage associated to conventional concrete. For the 28th day curing period, the SBF dosage was 1%, 2%, 3% and 4% in the LFC; there was an rise in the compressive strength of about 3.65%, 8.9%, 29.21% and 53.37% associated to the control concrete was observed. And after that, there is a reduction in the compressive strength of about 10.86% for 5% SBF dosage compared to control concrete was noted. For the 56th day curing period, the SBF dosage as 1%, 2%, 3% and 4% in the LFC, there is increase in the compressive strength about 3.73%, 7.76%, 28.57% and 50.62% compared to the control concrete was observed. And after that there is a reduction in the compressive strength of about 9.63% for 5% SBF dosage related to control concrete. The increase in compressive strength rate for 7th, 28th and 56th day for 1% dosage of SBF in LFC was observed in the above-mentioned mixes. An increase in compressive strength with the addition of short sugarcane bagasse fibers (SBF) in cementitious composites has been reported by Hernandez-Olivares et al.56. Similarly, the inclusion of natural fibers generally enhances compressive strength. However, the rate of strength improvement varies depending on fiber type, volume fraction, and aspect ratio, as noted by Amran et al.54. Furthermore, Falliano et al.57 emphasized that fiber content, curing conditions, and dry density all significantly influence the compressive strength of fiber-reinforced foamed concrete. These findings align well with the observed trends in this study, highlighting the complex interplay of fiber characteristics and processing parameters on mechanical performance.

At 4% content, the SBF is well-dispersed within the cementitious matrix, which promotes efficient stress transfer between the matrix and fibers. This allows the fibers to bridge microcracks effectively and delay crack propagation under load, thereby enhancing mechanical performance. Additionally, the natural fibrous nature of SBF contributes to better post-crack behavior. At 4%, this contributes to improved toughness and energy absorption without overly compromising the mix’s homogeneity. However, beyond 4%; specifically at 5% SBF, the compressive strength of the LFC began to decline. This reduction can be attributed to several interrelated factors. Higher fiber content increases the likelihood of fiber agglomeration, leading to clustering within the matrix. These clusters form weak zones where stress can concentrate, resulting in premature failure under mechanical loading. Furthermore, the addition of excessive fibers significantly reduces the workability of the mix, making uniform compaction more difficult to achieve. This can lead to increased void content and poor interfacial bonding in the interfacial transition zones (ITZ), both of which negatively affect compressive strength. Moreover, there is a fiber-matrix imbalance at higher dosages; when the fiber volume exceeds the optimal threshold, it disrupts the continuity and integrity of the cementitious matrix, which is crucial for withstanding compressive forces.

Flexural strength

An increase in the flexural strength of LFC as 8.77%, 14.04%, 42.11% and 71.93% for LFC with dosage as 1%, 2%, 3% and 4% compared to the control concrete was noted for 7th day flexural strength, is observed from Fig. 16. And on further increase in the dosage of SBF to 5% in LFC, there is a decrease in the flexural strength of about 7.02% compared to control concrete. For the 28th day curing period, there is an increase in the flexural strength of about 5.88%, 13.24%, 35.29%, and 63.24% for the LFC with dosage as 1%, 2%, 3% and 4% compared to control concrete was observed. As observed for the 7th day strength, on further increase in the SBF dosage to 5% in LFC, there is a decrease in the flexural strength about 8.82% compared to control concrete. For the 56th day curing period, there is an increase in the flexural strength of about 5.19%, 11.69%, 33.77% and 59.74% for the LFC with dosage as 1%, 2%, 3% and 4% compared to control concrete was observed. Similar to earlier curing periods, on further increasing the dosage of SBF to 5%, there was a decrease in the flexural strength of about 7.79% compared to control concrete. A decrease in the rate of flexural strength gain over the curing period was observed, although the overall increase in flexural strength is attributed to the higher tensile strength and random distribution of sugarcane bagasse fibers (SBF), which help resist crack propagation. Amran et al.54 reported an approximately 54% increase in flexural strength for LFC containing 2% natural fibers compared to fiber-free LFC at 28 days. Similarly, Falliano et al.57 highlighted the influence of fiber content, curing conditions, and dry density on the flexural strength of fiber-reinforced foamed concrete. Moreover, Falliano et al.58 noted that adding about 5% microfibers enhances flexural strength by shifting failure behavior from brittle to more ductile. The non-uniform distribution of fibers also affects flexural strength, as reported by Raj et al.59, who emphasized that fibers inhibit crack propagation, thereby significantly improving flexural performance. These findings are consistent with the trends observed in this study, underscoring the important role of fiber characteristics and distribution in enhancing LFC’s flexural properties.

Splitting tensile strength

The effect of the different dosages of SBF on the LFC is shown in Fig. 17. By increasing the dosage of SBF from 1%, 2%, 3% and 4%, there is an increase in the spilt tensile strength of about 8.57%, 14.29%, 54.29% and 74.29% compared to control concrete was observed for the 7th day curing period. Furthermore, by increasing the dosage of SBF by about 5%, there is a decrease in the spilt tensile strength of about 5.71% compared to control concrete. For the 28th day curing period, the increase in the dosage of SBF as 1%, 2%, 3% and 4%, there is an increase in the spilt tensile strength of about 4.76%, 11.90%, 45.24% and 69.05% compared to control concrete. And on further increase in the SBF dosage of about 5%, there is a decrease in the spilt tensile strength of about 9.52% compared to control concrete. An increase in the spilt tensile strength up to 4% of SBF, is due to the higher tensile strength of SBF and the prevention of cracks in the LFC. The incorporation of natural fibers in cement composites has been shown to enhance tensile strength, as reported by Abedom et al.60. Specifically, the addition of sugarcane bagasse fiber (SBF) has been found to increase tensile strength, as noted by Vallejos et al.49. Amran et al.54 documented approximately a 40% increase in split tensile strength with the inclusion of 3% basalt fiber. This improvement is largely attributed to the slower crack propagation in fiber-reinforced specimens, which delays failure compared to those without fibers, as explained by Wang et al.61. Furthermore, Raj et al.59 highlighted that the enhancement in split tensile strength from both natural and synthetic fibers is influenced by their higher tensile capacity and their non-uniform, random distribution within the matrix. These findings corroborate the results observed in this study, emphasizing the significant role of fiber reinforcement in improving tensile performance.

Thermal conductivity

The influence of the SBF on the thermal conductivity of the LFC is depicted in Fig. 18. The thermal conductivity of the LFC without SBF is observed as 0.3123 W/mK. On the introduction of the SBF as 1%, 2%, 3% and 4%, there is a rise in the thermal conductivity as 0.3189 W/mK, 0.3245 W/mK, 0.3297 W/mK and 0.3365 W/mK was observed. And on further increase in the SBF dosage of about 5% in the LFC, there is a decrease in the thermal conductivity as 0.3276 W/mK. The introduction of fibers into LFC has been shown to reduce thermal conductivity, primarily due to the non-uniform distribution of fibers within the matrix, as observed by Jhatial et al.62. Specifically, thermal conductivity decreases with increasing SBF dosage, which is attributed to the disruption of pore continuity in the LFC. According to Mydin et al.63, the thermal conductivity of foamed concrete is largely governed by pore connectivity and distribution within the cementitious system. Higher heat flow corresponds to increased thermal conductivity, while the presence of SBF affects this property through its chemical composition characterized by a high cellulose content and low extractives resulting in reduced thermal conductivity, as reported by Onesippe et al.64. In fact, Onesippe et al.64 documented up to a 25% decrease in thermal conductivity for LFC with SBF dosages up to 3% compared to control mixes. Additionally, the overall thermal conductivity of LFC depends on the relative proportions and thermal properties of its constituents. Since air has significantly lower thermal conductivity than solid materials, the high void content in LFC strongly influences its thermal behavior, as noted by Amran et al.54. Moreover, variations in LFC density, linked to void volume, directly affect thermal conductivity, highlighting the importance of porosity control in thermal performance.

Thermal diffusivity

The influence of the SBF dosage on thermal diffusivity was noted in Fig. 19. The thermal diffusivity of control LFC without SBF fibers was 0.521 m2/s. And on increasing the dosage of SBF as 1%, 2%, 3% and 4% in LFC, there is an increase in the thermal diffusivity of about 0.528 m2/s, 0.535 m2/s, 0.544 m2/s and 0.551 m2/s. And on further increase in the dosage of SBF to 5%, a decrease in the thermal diffusivity of about 0.541 m2/s was observed. The thermal diffusivity increased by about 1.27%, 2.72%, 4.43% and 5.62% compared to control concrete. When the SBF dosage is increased to 5%, a decrease in the thermal diffusivity was observed of about 3.8% compared to the control concrete. An increase in thermal diffusivity of LFC was observed with the addition of SBF up to a 4% dosage, attributed to the thermal energy storage capacity of SBF. However, beyond this dosage, increased pore connectivity within the fiber network leads to a reduction in thermal diffusivity, as reported by Mydin et al.65. This initial increase in thermal diffusivity is linked to the disruption of pore connectivity caused by SBF incorporation, which limits heat flow through the LFC matrix, as further explained by Mydin63.

The increase in thermal conductivity with higher proportion of SBF in LFC can be explained by several factors that are all associated to the physical properties of the fibers and how they affect the concrete matrix. Primarily, SBF is organic and has little thermal conductivity yet adding them to LFC usually makes the air pockets smaller. The fibrous network breaks up the even distribution of air spaces that the foaming process makes as the SBF concentration goes up. This makes the matrix denser and less aerated. Since air doesn’t carry heat very well, lowering the amount of air in the composite makes it conduct heat better overall. Additionally, the SBF themselves might make heat bridges inside the matrix. As they get more concentrated, they make it easier for heat to go through solid channels instead of the air-filled pores that insulate. This change in structure makes the material better at transferring heat. Third, more SBF usually means better packing density and less porosity. This is good for strength and longevity, but it also means there are fewer air pockets that might stop heat flow. Because of this, the total resistance to heat transmission goes down, which makes thermal conductivity increase.

The sudden rise in thermal conductivity upon the addition of 5% SBF is possibly attributed to fiber clumping and enhanced void formation within the LFC matrix. When there are an excessive amount of fibers, they may bond together, which makes additional air pockets and microvoids surrounding SBF bundles. These further air gaps work as thermal barriers by breaking up the solid heat transfer channels, which lowers the entire thermal conductivity of LFC. Furthermore, the larger fiber volume may make the matrix more porous and produce weak points, which would make LFC even better at a barrier, even if the structure is normally more compact with less SBF.

As the volume fraction of SBF in the LFC increased, the thermal conductivity and compressive strength (Fig. 15) transformed into opposite ways. With the addition of 4% SBF, compressive strength improved steadily until it reached an ideal point. This was because the SBF bonded better with the matrix and the pores were refined, which improved load transfer and mechanical performance. On the other hand, thermal conductivity progressively increased up to 4% SBF content. This was because the matrix was denser and had less insulating air gaps, which made it easier for heat to get through. However, at 5% SBF, the compressive strength decreased because the fibers may have clumped together, and the matrix may have broken down. The thermal conductivity, on the other hand, improved unexpectedly, probably because the extra fibers created more voids and air pockets that acted as thermal barriers. This opposite behavior shows the trade-off between the mechanical strength and thermal insulation capabilities of SBF-reinforced LFC.

Specific heat capacity

The effect of the SBF dosage on the specific heat capacity was reported in Fig. 20. The specific heat capacity of the control LFC without SBF was noted as 1012 J/kg K. By increasing the SBF dosage as 1%, 2%, 3%, 4% and 5% in the LFC, there is an upsurge in the specific heat capacity as 1000 J/kg K, 992 J/kg K, 983 J/kg K, 976 J/kg K, and 985 J/kg K. On comparing to the control concrete without fibers, there is a decrease in the specific heat capacity of about 1.19%, 1.98%, 2.87%, 3.56% and 2.67% for the 1%, 2%, 3%, 4% and 5% dosage of SBF in the LFC. The low amount of entrapped air in the LFC mix reduces its ability to store heat within the pores, causing more heat to be released into the surroundings. This phenomenon explains why increasing the SBF dosage leads to a decrease in the specific heat capacity of the LFC mix63. Since LFC is characterized by low density, the air pores largely govern its thermal behavior, resulting in higher heat transfer rates. Furthermore, the increase in SBF content reduces the specific heat capacity due to the fiber’s lower water absorption capacity, which means less energy is required to raise the temperature of the material at constant pressure, as noted by Mydin et. al.66.

SEM analysis

Figure 21 visualizes the microstructural morphology of LFC. The matrix comprises two distinct phases: the air-void phase, produced by the incorporation of preformed foam, and the solid phase, representing the hydrated cement paste, as shown in Fig. 21a. The bubbles introduced into the LFC matrix form microporous structures that weaken interfacial bonding within the matrix. On the other hand, Fig. 21b shows LFC reinforced with a 4% SBF weight fraction, in which the SBF fibers are embedded within the LFC cementitious matrix, effectively reducing both the number and size of the voids. The presence of SBF enhances crack-bridging capacity and may mitigate microcrack formation. Overall, the inclusion of SBF dramatically modifies the microstructure of LFC, promoting densification and improved internal cohesion.

Figure 21c depicts the LFC mixture containing 5% SBF. This mix clearly indicates indications of SBF agglomeration, which intensifies the probability of clumping within the cement-based matrix. The SBF clustering provide discrete weak zones that disrupt matrix regularity, facilitating stress concentration and leading to premature disintegration under mechanical strain. Moreover, the high SBF content considerably decreases the workability of the fresh mix, affecting the attainment of adequate compaction. Furthermore, inadequate SBF dispersion adversely impacts the state of the interfacial transition zones (ITZ), degrading the link between the SBF and the matrix, hence diminishing strength properties.

The incorporation of SBF into LFC contributes to the formation of hybrid composites, as reported by El-Baky et al.67, enhancing the overall structural and functional performance of the material. Additionally, the water-to-cement ratio plays a significant role in influencing pore structure. As shown by Qian et al.68, a higher water-to-cement ratio results in a greater number of small pores and an increased surface area, which in turn leads to thinner pore walls and more interconnected pore networks, as confirmed through SEM analysis.

Pore structure analysis

From Table 5, it is noted that with an increase in the dosage of SBF content, there is a decrease in the intrusion volume of up to 4% of SBF content, and after that, an increase in the intrusion volume is observed. For 1%, 2%, 3% and 4% of SBF content, there is a decrease in the intrusion volume of about 13.68%, 20.41%, 25.52% and 33.55% was observed compared to control FC. Further increase in the SBF content of about 5% and an increase in the intrusion volume of about 27.14% compared to control concrete was noted. The average pore diameter for the LFC with SBF content of 1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, and 5% obtained 11.40%, 16.67%, 21.58%, 25.79%, and 20.35% reduction compared to control concrete. A similar trend for the bulk density and permeability was observed. In addition, the decrease in the bulk density for the FC with SBF content of 1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, and 5% was about 4.41%, 7.03%, 9.31%, 13.34% and 9.30% compared to the control concrete. The relationship between the various pore structure parameters is represented in Fig. 22a–f. Chen et al.69 investigated the impact of pore structure parameters on the permeability characteristics of foamed concrete (FC), highlighting their direct influence on durability. Additionally, Li et al.70 explored how fiber type, size, distribution, and content affect both the mechanical properties and pore structure of fiber-reinforced FC. These findings were further supported by Li et al.71, who confirmed the influence of fibers on mechanical and durability properties through microstructural analysis and established relationships between these performance parameters. Furthermore, Li et al.71 examined the effect of various fiber types on pore structure and their corresponding impact on thermal performance, which was validated using SEM imaging. These studies collectively underscore the critical role of fiber characteristics and pore structure in optimizing the performance of fiber-reinforced FC.

Relationship between the properties

Spilt tensile strength and compressive strength

A relationship between the spilt tensile strength and compressive strength of 28 days for FC with the help of SBF was proposed, as shown in Fig. 23a. The relationships proposed in the various literatures and the international standards were depicted in Table 6 as power equations. Hence, in this study, the power equation is also proposed for the two parameters, as depicted in Eq. 2, with a higher R2 value of 0.987. Based on the R2 value, the proposed equation shows more satisfied models. Three upper predictions of the models and two lower predictions of the models from the literature compared to the experimental work and proposed equation in this study are shown in Fig. 23b.

Flexural strength and compressive strength

The association between the flexural strength and compressive strength for 28 days of FC with SBF is depicted in Fig. 24a. Various relationships, as proposed by the literature and the international standards, were depicted in Table 7 in the form of power equations. Hence, in this study, the power equation is also proposed for the two parameters as depicted in Eq. (9), with a high R2 value of 0.995. Based on the R2 value, the proposed model can show the most satisfactory value. The two upper predictions of the models and major models are lower predictions from the literature compared to the experimental work, and the proposed equation in this study is shown in Fig. 24b.

Modulus of elasticity and compressive strength

Association between the MoE and compressive strength for 28 days of FC with SBF is depicted in Fig. 25a. Various relationships as proposed in the various literatures and the international standards was depicted in Table 8 in the form of power equations. Hence, in this study also the power equation is proposed for the two parameters as depicted in the Eq. 16. Influence of the various models from the literatures compared to the experimental work and proposed equation in this study was shown in Fig. 25b.

Ultrasonic pulse velocity and compressive strength

The relationship between the different types of UPV and compressive strength at 28 days arrived in the form of a polynomial equation as depicted in Fig. 26a–c. The R2 value for the different types of UPV and compressive strength at 28 days is more than 0.85, which depicted that the relationship is very strong. Equations 23, 24 and 25 show the polynomial equation for the different types of UPV and compressive strength. Various models from the literature are depicted in Table 9.

A relationship between the compressive strength of 30 MPa and the UPV was proposed by Nam et al., 2024, which is depicted in Eq. (2). The study also extended the comparison to conventional concrete; the slope for the LPC is lower, and a similar coefficient of determination was noted. The relationship between the compressive strength and the UPV was proposed as an exponential function was studied by Lee et al.84. A higher coefficient of determination (R2) for the exponential equation was observed. There is a change in the microstructure for the concrete having higher compressive strength; hence, UPV is not a governing factor in determining the higher compressive strength. From Fig. 26d–f, it is noted that the two models are overestimated, and all other models are underestimating the compressive strength of LFC. The model proposed by Pyszniak 85. is nearer to the model predicted by the current study.

Study limitations and future directions

This investigation offers significant insights into the impact of sugarcane bagasse fiber (SBF) on lightweight foamed concrete (LFC) properties; nonetheless, some limitations must be addressed in subsequent research.

-

1.

This study analyzed SBF content within a defined range (0% to 5%). Future research may examine a wider range of fiber contents and assess the impact of extremely high or low fiber levels on LFC characteristics.

-

2.

The experimental results were derived under regulated laboratory circumstances, which may not entirely reflect the behavior of LFC in practical applications. Field testing is essential to evaluate the performance of SBF-reinforced LFC under real construction situations, encompassing exposure to environmental variables like as temperature variations, humidity, and load-bearing stresses.

-

3.

The research concentrated on short-term durability characteristics. Prolonged testing, including accelerated aging and exposure to diverse environmental cycles, would facilitate the assessment of the long-term performance and durability of LFC-SBF composites.

-

4.

Although the results are encouraging at the laboratory level, subsequent research must tackle the obstacles associated with expanding the application of SBF in LFC for extensive construction endeavors. This entails evaluating the viability of large-scale production of LFC-SBF mixtures and comprehending the possible problems related to mix uniformity, cost, and quality assurance.

-

5.

Subsequent analyses could evaluate the performance of LFC-SBF composites against other natural fiber-reinforced concrete systems and synthetic fiber composites to ascertain the relative benefits of SBF in LFC.

In conclusion, although the present study provides significant insights into the viability of SBF as a reinforcement material for LFC, it is imperative to extend the research through long-term, real-world testing and to investigate additional parameters to comprehensively grasp its practical application and potential for large-scale utilization.

Conclusions

This work examined the mechanical, microstructural, and durability characteristics of leight-weight foamed concrete (LFC) composites reinforced with sugarcane bagasse fiber (SBF). The workability, density, and ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) were also assessed. The following findings are derived from the analysis:

-

1.

The slump flow consistently diminished as the SBF weight fraction in the LFC mixtures escalated from 1 to 5%. The mix containing 5% SBF exhibited the lowest slump value of 203 mm, whereas the control mix (without SBF) demonstrated the highest value of 253 mm. In parallel, dry density exhibited a slight rise from day 7 to 56, correlating with both the rising SBF content and extended curing duration.

-

2.

The incorporation of SBF markedly influences LFC’s water absorption capacity and permeable porosity. As the SBF weight fraction escalates from 1 to 5%, both parameters exhibit a progressive decline, indicating enhanced matrix densification and reduced connectivity.

-

3.

LFC drying shrinkage typically exhibits three unique patterns. Initially, immediate shrinkage transpires quickly after the commencement of the drying process, and this tendency endures for up to 7 days post-test. Among the various weight fractions of SBF, the LFC with 4% SBF exhibited the lowest drying shrinkage. As the SBF in the LFC rises, the ultrasonic pulse velocity also tends to increase. The use of 4% SBF with LFC yielded the highest ultrasonic pulse velocity measurements.

-

4.

The SEM results demonstrate that the presence of SBF enhances the bridging force across the matrix fracture and may mitigate microcracking. The insertion of SBF markedly modifies the microstructure of LFC.

-

5.

Seven new predictive models were provided based on cube compressive strength, and a comparison of these models with several existing models from the literature and experimental data was presented.

-

6.

This study is constrained to a maximum SBF concentration of 5% and a target LFC density of 1000 kg/m3, feasibly limiting the generalizability of the results. The durability under harsh climatic conditions and the long-term performance were not evaluated. Furthermore, the laboratory-scale environment may not accurately represent real-world settings.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper.

References

Amran, Y. H. M. Influence of structural parameters on the properties of fibred-foamed concrete. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 5, 16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41062-020-0262-8 (2020).

Ramamurthy, K., Nambiar, E. K. K. & Ranjani, G. I. S. A classification of studies on properties of foam concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 31, 388–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2009.04.006 (2009).

Lesovik, V. et al. Improving the behaviors of foam concrete through the use of composite binder. J. Build. Eng. 17, 101414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101414 (2020).

Ahmad, F., Qureshi, M. I., Rawat, S., Alkharisi, M. K. & Alturki, M. E-waste in concrete construction: Recycling, applications, and impact on mechanical, durability, and thermal properties—A review. Innov. Infrastruct. Sol. 10(6), 246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41062-025-02038-2 (2025).

Kearsley, E. P. & Wainwright, P. J. Porosity and permeability of foamed concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 31, 805–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(01)00490-2 (2001).

Siddique, R. & Cachim, P. Waste and Supplementary Cementitious Materials in Concrete: Characterisation, Properties and Applications 1–599 (Woodhead Publishing, 2018).

Modani, P. O. & Vyawahare, M. R. Utilization of bagasse ash as a partial replacement of fine aggregate in concrete. Procedia Eng. 51, 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2013.01.007 (2013).

Li, Y., Chai, J., Wang, R., Zhang, X. & Si, Z. Utilization of sugarcane bagasse ash (SCBA) in construction technology: A state-of-the-art review. J. Build. Eng. 56, 104774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104774 (2022).

Oktarini, D., Mohruni, A.S., Sharif, S. & Yanis, M. Optimization of sugarcane process production using response surface methodology (RSM) and artificial neural networks (ANNs). J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. (2025) 42–54. https://doi.org/10.37934/araset.60.1.4254.

Ahmad, F. et al. Effect of metakaolin and ground granulated blast furnace SLAg on the performance of hybrid fibre-reinforced magnesium oxychloride cement-based composites. Int. J. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40999-025-01074-4 (2025).

Hadipramana, J., Samad, A. A. A., Zaidi, A. M. A., Mohammad, N. & Riza, F. V. Effect of uncontrolled burning rice husk ash in foamed concrete. Adv. Mater. Res. 626, 769–775. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.626.769 (2013).

Bing, C., Zhen, W. & Ning, L. Experimental research on properties of high-strength foamed concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 24, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0000353 (2012).

Dawood, E. T. & Hamad, A. J. Toughness behaviour of high-performance lightweight foamed concrete reinforced with hybrid fibres. Struct. Concr. 16, 496–507. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.201400087 (2015).

Abbas, W., Dawood, E. & Mohammad, Y. Properties of foamed concrete reinforced with hybrid fibres. In: MATEC Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France., 162, 02012. (2018).

Hulimka, J., Krzywoń, R. & Jędrzejewska, A. Laboratory tests of foam concrete slabs reinforced with composite grid. Procedia Eng. 193, 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.06.222 (2017).

Mindess, S. Developments in the Formulation and Reinforcement of Concrete (Woodhead Publishing, 2019).

Yip, C. C., Marsono, A. K., Wong, J. Y. & Amran, M. Y. H. Flexural strength of special reinforced lightweight concrete beam for Industrialised Building System (IBS). J. Teknol. 77, 187–196. https://doi.org/10.11113/jt.v77.3505 (2015).

Mydin, M A. O, Musa, M. & Ghani, A.N.A. Fiber glass strip laminates strengthened lightweight foamed concrete: Performance index, failure modes and microscopy analysis. In: AIP Conference Proceedings., 2016(1), 020111. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5055513

Nasir, A., Butt, F. & Ahmad, F. Enhanced mechanical and axial resilience of recycled plastic aggregate concrete reinforced with silica fume and fibers. Innov. Infrastruct. Sol. 10(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41062-024-01803-z (2024).

Maganti, T. R., Kandikuppa, C. S., Gopireddy, H. K. R., Dugalam, R., & Boddepalli, K. R. Enhanced compressive strength and impact resistance in hybrid fiber reinforced ternary-blended alkali-activated concrete: An experimental, weibull analysis and finite element simulation. Composites Part C Open Access. 100629. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomc.2025.100629

Maganti, T. R. & Boddepalli, K. R. Synergistic enhancement of compressive strength and impact resistance in alkali-activated fiber-reinforced concrete through silica fume and hybrid fiber integration. Constr. Build. Mater. 471, 140702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.140702 (2025).

Flores-Johnson, E. A. & Li, Q. M. Structural behaviour of composite sandwich panels with plain and fibre-reinforced foamed concrete cores and corrugated steel faces. Compos. Struct. 94, 1555–1563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2011.12.017 (2012).

Jones, M.R. & McCarthy, A. Behaviour and assessment of foamed concrete for construction applications. In: Proc. of the International Conference, University of Dundee, Scotland, UK. 61–88 (2005).

Othuman Mydin, M. A. & Soleimanzadeh, S. Effect of polypropylene fiber content on flexural strength of lightweight foamed concrete at ambient and elevated temperatures. Adv. Appl. Sci. Res. 3, 2837–2846 (2012).

Mahzabin, M. S., Hock, L. J., Hossain, M. S. & Kang, L. S. The influence of addition of treated kenaf fibre in the production and properties of fibre reinforced foamed composite. Constr. Build. Mater. 178, 518–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.05.169 (2018).

Othuman Mydin, M. A. & Mohd Zamzani, N. Coconut fiber strengthen high performance concrete: Young’s modulus, ultrasonic pulse velocity and ductility properties. Int. J. Eng. Technol. UAE 7(2), 284–287. https://doi.org/10.14419/ijet.v7i2.23.11933 (2018).

Liu, Y., Wang, Z., Fan, Z. & Gu, J. Study on properties of sisal fiber modified foamed concrete. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 744, 012042. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/744/1/012042 (2020).

Amarnath, Y.; Ramachandrudu, C. Properties of Foamed Concrete with Sisal Fibre. In: Proc. of the 9th International Concrete Conference 2016: Environment, Efficiency and Economic Challenges for Concrete. University of Dundee, Dundee, UK. 4–6. (2016).

Flores-Johnson, E. A. et al. Mechanical characterization of foamed concrete reinforced with natural fibre. Mater. Res. Proc. 7, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.21741/9781945291838-1 (2018).

BS EN 197-1; Cement—Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. British Standards Institute: London, UK. (2011).

BS 3148:1980 Methods of Test for Water for Making Concrete (Including Notes on the Suitability of the Water). British Standards Institute: London, UK. (1980).

ASTM C33-03; Standard Specification for Concrete Aggregates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, United States. (2003).

ASTM C796/C796M-19; Standard Test Method for Foaming Agents for Use in Producing Cellular Concrete Using Preformed Foam. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, United States. (2019).

ASTM C230-C 230M; Standard Specification for Flow Table for Use in Tests of Hydraulic Cement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, United States. (2003).

BS EN 1881-122; Testing Concrete—Method for Determination of Water Absorption. British Standards Institute: London, UK, 2011.

BS EN 12504-4; Testing Concrete in Structures Determination of Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity. British Standards Institute: London, UK. (2021).

ASTM C878/C878M; Standard Test Method for Restrained Expansion of Shrinkage-Compensating Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, United States. (2014).

BS EN 12390-3; Testing Hardened Concrete—Compressive Strength of Test Specimens. Standards Institute: London, UK. (2019).

BS EN 12390-5; Testing Hardened Concrete—Flexural Strength of Test Specimens. Standards Institute: London, UK. (2019).

BS EN 12390–6—Testing Hardened Concrete—Tensile Splitting Strength of Test Specimens. Standards Institute: London, UK. (2023).

ASTM C469–02; Standard Test Method for Static Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete in Compression. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, United States. (2014).

ASTM C177–19; Standard Test Method for Steady-State Heat Flux Measurements and Thermal Transmission Properties by Means of the Guarded-Hot-Plate Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, United States. (2019).

ISO 16700; Microbeam Analysis—Scanning Electron Microscopy—Guidelines for Calibrating Image Magnification. Technical Committee : ISO/TC 202/SC 4 ICS : 37.020. (2016).

ASTM D4404-18; Standard Test Method for Determination of Pore Volume and Pore Volume Distribution of Soil and Rock by Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, United States, (2018).

Jones, M. R. & Giannakou, A. Preliminary views on the application of foamed concrete in structural sections using pulverized fuel ash as cement or fine aggregate. Mag. Concr. Res. 57(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1680/macr.57.1.21.57866 (2010).

Le, D. H., Sheen, Y. N. & Lam, M. N. T. Self-compacting concrete with sugarcane bagasse ash–ground blast furnace slag blended cement: fresh properties. EES Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 143(1), 012019. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/143/1/012019 (2010).

Jagadesh, P., Ramachandramurthy, A., Murugesan, R. & Sarayu, K. Micro-analytical studies on sugar cane bagasse ash. Sadhana 40, 1629–1638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12046-015-0390-6 (2015).

Rawat, S., Saliba, P., Estephan, P. C., Ahmad, F. & Zhang, Y. Mechanical performance of hybrid fibre reinforced magnesium oxychloride cement-based composites at ambient and elevated temperature. Buildings 14(1), 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14010270 (2024).

Vallejos, M. E. et al. Composites materials of thermoplastic starch and fibers from the ethanol-water fractionation of bagasse. Ind. Crops Prod. 33, 739–746 (2011).

Raj, B., Sathyan, D., Madhavan, M. K. & Raj, A. Mechanical and durability properties of hybrid fiber reinforced foam concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 245, 118373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118373 (2020).

Roslan, A. F., Awang, H. & Mydin, M. A. O. Effects of various additives on drying shrinkage, compressive and flexural strength of lightweight foamed concrete (LFC). Adv. Mater. Res. 626, 594–604. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.626.594 (2013).

Liu, X. et al. Simulation of ultrasonic propagation in porous cellular concrete materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 285, 122852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122852 (2021).

Gong, J. & Zhang, W. The effects of pozzolanic powder on foam concrete pore structure and frost resistance. Constr. Build. Mater. 208, 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.02.021 (2019).

Amran, Y. H. M. et al. Performance properties of structural fibred-foamed concrete. Results Eng. 5, 100092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2019.100092 (2020).

Zhou, H. & Brooks, A. L. Thermal and mechanical properties of structural lightweight concrete containing lightweight aggregates and fly-ash cenospheres. Constr. Build. Mater. 198, 512–526 (2019).

Hernandez-Olivares, F., Medina-Alvarado, R. E., Burneo-Valdivieso, X. E. & Zuniga-Suarez, A. R. Short sugarcane bagasse fibers cementitious composites for building construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 247, 118451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118451 (2020).

Falliano, D., Domenico, D. D., Ricciardi, G. & Gugliandolo, E. Compressive and flexural strength of fiber-reinforced foamed concrete: Effect of fiber content, curing conditions and dry density. Constr. Build. Mater. 198, 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.197 (2019).

Falliano, D., Parmigiani, S., Suarez-Riera, D., Ferro, G. A. & Restuccia, L. Stability, flexural behavior and compressive strength of ultra-lightweight fiber-reinforced foamed concrete with dry density lower than 100kg/m3. J. Build. Eng. 51, 104329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104329 (2022).

Raj, A., Sathyan, D. & Mini, K. M. Physical and functional characteristics of foam concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 221, 787–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.06.052 (2019).

Abedom, F. et al. Development of natural fiber hybrid composites using sugarcane bagasse and bamboo charcoal for automotive thermal insulation materials. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 2508840. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/2508840 (2021).

Wang, D., Ju, Y., Shen, H. & Xu, L. Mechanical properties of high-performance concrete reinforced with basalt fiber and polypropylene fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 197, 464–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.181 (2019).

Jhatial, A. A., Goh, W. I., Mohammad, N., Alengaram, U. J. & Mo, K. H. Effect of polypropylene fibres on the thermal conductivity of light weight foamed concrete. MATEC Web Conf. 150, 03008. https://doi.org/10.10151/matecconf/201815003008 (2018).

Mydin, M. A. O. Assessment of thermal conductivity, thermal diffusivity and specific heat capacity of lightweight aggregate foamed concrete. J. Teknologi 78(5), 477–482 (2016).

Onesippe, C. et al. Sugar cane bagasse fibres reinforced cement composites: Thermal considerations. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 41(4), 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2010.01.002 (2010).

Mydin, M. A. O. et al. Thermal conductivity, microstructure and hardened characteristics of foamed concrete composite reinforced with raffia fiber. J. Market. Res. 26, 850–864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.07.225 (2023).

Mydin, M. A. O., Mohamad, N., Samad, A. A. A., Johari, I. & Munaaim, M. A. C. Durability performance of foamed concrete strengthened with chemical treated (NaOH) coconut fiber. AIP Conf. Proc. 2016, 020109. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5055511 (2018).

El-Baky, M. A. A., Megahed, M., El-Saqqa, H. H. & Alshorbagy, A. E. Mechanical properties evaluation of sugarcane bagasse—Glass/polyester composites. J. Nat. Fibers 18(8), 1163. https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2019.1687069 (2021).