Abstract

This paper investigates the detection and isolation of false data injection (FDI) attacks in large-scale smart grids. Attackers can devise sophisticated false data injection strategies by tampering with data at the communication layer, potentially bypassing conventional detection mechanisms based on Kalman filters, thereby posing significant threats to grid security. To mitigate such risks, this paper proposes a detection and isolation framework based on adaptive residual observers. The study specifically addresses the distinctive characteristics of FDIAs, with in-depth analysis of generator power output dynamics, biased load conditions, and historical load profiles. An innovative algorithm within the adaptive residual observer framework is introduced to identify anomalous regions within the grid that may be compromised by stealth attacks. The algorithm employs robust analytical redundancy relationships to correlate residual signals with dynamically adjusted thresholds. Through continuous residual monitoring, the observer can detect deviations indicative of potential attacks. The isolation of affected regions is achieved through a consistency verification process supported by a novel logic judgment matrix, which compares observed behavioral patterns against expected operational norms. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, simulation studies are conducted using the IEEE 18-generator 37-bus smart grid model, with performance comparisons to existing methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background

Large-scale power systems constitute one of the most complex cyber-physical systems (CPS) in modern infrastructure1,2. Recent advancements in smart grid control and monitoring, particularly the integration of bidirectional communication and distributed intelligence, have significantly improved power system reliability and operational safety3,4. However, these technological enhancements introduce vulnerabilities when implemented without adequate security measures. Of particular concern is the open architecture of smart grid communication networks, which creates attack surfaces susceptible to cyber threats targeting wide-area measurement systems (WAMS), supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems, and other critical operational components5,6. Such attacks can degrade grid efficiency, compromise control stability, and disrupt service delivery. Consequently, there is increasing emphasis on developing robust supervisory frameworks capable of detecting, analyzing, and mitigating cyber threats to safeguard smart grid operations, protect utility assets, and ensure the integrity of consumer-facing infrastructure.

Over the past decade, substantial research efforts have been dedicated to enhancing communication system security in power grids. Specifically, within communication channels connecting transformer substations to control centers, minimum cut relaxation techniques have been widely adopted as a primary defense mechanism against potential cyberattack pathways7. Concurrently, a cost-constrained optimization framework was proposed to mitigate cyber stealth attacks through strategic security resource allocation8. While these methods effectively restrict false data injection (FDI) attack execution in power systems, their communication channel-level algorithmic designs lack inherent capabilities for detecting such malicious activities9,10. This paper focuses on stealth attacks targeting measurement outputs of load communication channels, as first identified in11,12. Studies13,14 demonstrated that attackers can manipulate system operations and mislead smart grid decision-making processes while evading bad-data detection alarms in the control center.

Research on related works

To swiftly respond to injected stealth attacks in power systems, current detection methods can be categorized into two primary approaches: data-driven and model-based methods15. The data-driven approach involves the collection and analysis of multi-source heterogeneous data, including network traffic and system logs, utilizing machine learning algorithms to construct models for detecting potential attacks16. In17, Alankrita et al., explored the susceptibility of network-connected DC Microgrids to cyber threats, specifically focusing on combating FDI attacks. In18, Wang et al., developed an data-driven attack detection and location method in DC Microgrids. A machine learning-powered restoration framework was introduced to counteract distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) disruptions and malicious data integrity breaches19. A detection model using spatial-temporal features against FDI attacks was developed, where graph convolutional network was employed to disentangle the interactions among buses; temporal convolutional network was constructed to extract the temporal features20. An FDI attack fast detection and pinpoint localization framework was proposed, which can identify abnormal signals and attacked nodes from the unique topology structure and status contiguity of smart distribution networks21. In22, an innovative framework for the classification and detection of FDI attacks was proposed, which can mitigate the risk of strictly stealthy attacks, as any system integrity tampering by an attacker generates a bias. A novel data-driven framework to aid in system state estimation when the power system was under unobservable FDI attacks23. In24, a novel method for estimating and mitigating FDI Attacks was proposed to counter cyber threats targeting Load Frequency Control systems. Although the aforementioned data-based detection methods can effectively identify injected FDI attacks, the process of establishing datasets and the complexity of the models constrain their detection performance25. To address this critical limitation, control theory-based state estimation methodologies have been developed, providing advanced capabilities for detecting and isolating stealth attacks through systematic analysis of system-wide operational states. In26, an attack detection method was proposed, leveraging the multi-state matching approach and an enhanced generative adversarial network for similar daily data preprocessing. A detection and localization method for FDI attack based on the cosine similarity and the partition strategy and detection matrix27. In28, a novel detection and isolation method of FDI attacks against load frequency control was developed. To bolster the reliability and safety of large-scale smart grid systems, Yang et al., address the challenge of detecting FDI Attacks in such systems, taking into account process disturbances and measurement noise29. In30, a detection and location framework against biased load injection attacks consisting of three steps was proposed. In31, a classification of the proposed cyber resilience methods against cyber attacks for smart grids was proposed. While model-based detection methods effectively tackle the issues of data collection and model complexity, enhancing model accuracy and refining threshold design are crucial for improving their detection performance.

Motivated by the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes a decentralized architecture for detecting and isolating stealth attacks in large-scale interconnected power grids. Given the impracticality of centralized data collection and processing in smart grids due to their vast scale, the power system is partitioned into multiple areas based on network topology sparsity and stable power margins. Each area exhibits dense internal connections but sparse inter-area connections. To address potential control center command manipulations that alter load dynamics, we introduce a state observer-based algorithm employing nonlinear observers to detect abnormal signals within these areas. The detection mechanism formulates observed patterns through robust analytical redundancy relations between residuals and adaptive thresholds. Abnormal region isolation is achieved via consistency testing between a logic judgment matrix and the observed patterns. Focusing on the identified abnormal region, generator power variations are derived from control center data. Based on the quantitative relationship between generator power and load dynamics, we develop a decision algorithm to pinpoint loads directly targeted by stealth attacks. This approach isolates load power alterations resulting from malicious control commands. Finally, simulation tests validate the effectiveness of the proposed detection and isolation framework against False Data Injection (FDI) attacks. The primary contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

-

An adaptive residual observer-based attack detection method is proposed. By continuously monitoring these residuals, the proposed adaptive observers can be capable of identifying deviations that suggest the presence of stealth attacks. Additionally, an adaptive detection threshold is designed, by which the attack detection performance against FDI attacks can be improved.

-

A logic judgment matrix-based attack isolation method is developed. The isolation of the affected region under FDI attacks can be achieved via a consistency verification process, guided by a novel logic judgment matrix that evaluates the observed patterns against expected norms.

-

Comparing with works in30,32 and33, simulations on IEEE 37-bus grid system are presented to demonstrate the superiority of the proposed detection and isolation method against FDI attacks.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. “Problem formulation” formulates the regional division problem for large-scale power systems and provides an overview of False Data Injection (FDI) attacks. Section “Detection of false data injection Attack” presents the design of observer-based residual generation and adaptive threshold mechanisms. Section “Isolation of false data injection Attack” details the isolation of abnormal regions, along with biased load identification and prior load analysis. Section “Simulation results” provides a simulation example to validate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm. Section “Conclusion and future works” concludes the paper with a summary of key findings.

Problem formulation

In this section, we will depict the model of power systems and FDI attack, and then formulate the regional division problem.

Power system model

Considering a larger-scale, nonlinear dynamical power system, comprised of n generators and \(n+m\) buses with n corresponding generator terminal buses and m load buses, the rotor dynamics swing equations of generator \(g_{i}\) , \(g_{i}\in \left\{ g_{1},...,g_{n}\right\}\), can be described as11

where \(\delta _{i}\left( t\right)\), \(\omega _{i}\left( t\right)\) denote the rotor angle and frequency of generator \(g_{i}\), respectively, and \(\theta _{i}\left( t\right)\) is the voltage angle at the bus \(b_{i}\), \(b_{i}\in \left\{ b_{1},...b_{n+m}\right\}\). Denote \(E_{i}\), \(V_{i}\) to be the voltage modulus of generator \(g_{i}\) and bus \(b_{i}\), respectively. Diagonal matrices \(M_{i}\) and \(D_{i}\) are the generator inertial and damping coefficient, also \(z_{i}\), \(G_{ik}\) and \(B_{ik}\) are the reactance, conductance and susceptance of the transmission line \(\left\{ b_{i},b_{k}\right\}\). And the input \(P_{Mi}\) is mechanical power input.

Let \(P_{k}\), \(k\in \left\{ 1,...,n\right\}\) denote the total active power injecting into the generator terminal bus \(b_{k}\) as:

where the dependence of the variables on the time t is omitted for brevity.

Denote \(P_{l}\), \(l\in \left\{ n+1,...,n+m\right\}\), to be the active power injecting into the load bus \(b_{l}\) as

Then the dynamic model of the smart grid system can be described by the following differential algebraic equation

where

Then the dynamic model of the power system can be rewritten as follows

Remark 1

The observability of each group or subsystem is formally verified using rank tests on the matrices defining its dynamics. For a standard linear time-invariant system, this involves applying tests like the Hautus criterion or checking the rank of the observability matrix to the pair \((A_{ii}, C_i)\), which represents the group’s internal dynamics and its output measurement. This analysis determines whether the group’s internal states can be uniquely reconstructed from its outputs, even when interconnections from other groups are treated as unknown inputs or disturbances. In the more general case of a descriptor system characterized by the matrices (E, A, C), the test extends to a generalized rank condition on the system pencil \(\begin{pmatrix} sE - A \ C \end{pmatrix}\) to ensure finite observability. The impact of incorrectly assuming a group is unobservable is catastrophic for attack detection performance. This error breaches the fundamental design principle of residual decoupling, as the states and attacks of the assumed unobservable group are not isolated by a dedicated observer. Consequently, their dynamics leak into and corrupt the residuals of all other monitored groups. This inevitably causes false alarms, where normal fluctuations in the unobserved group are misinterpreted as attacks in observable ones, and missed detections, where actual attacks within the unobserved group go entirely unrecognized. The result is a complete breakdown of fault isolation credibility and a severely compromised diagnostic system.

False data injection attack

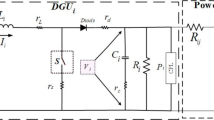

As one of typical false data injection attacks, the stealth attack mode is shown in Fig. 1.

An attacker compromises the cyber layer by gaining access to certain communication channels. This intrusion does not directly alter the actual load dynamics. However, the control center receives false measurements, which evade bad-data detection alarms. Consequently, the control center issues incorrect control commands. These flawed instructions lead to misguided actions. As a result, both load and generator power outputs are adversely affected. This enables the attacker to achieve their intended goal, jeopardizing the safe operation of the power system and endangering other electricity consumers. Based on this, we provide the following definition.

Definition 1

[34] \(\left( \text {Biased load}\right)\) Biased load is that the attacker has a direct impact on the load by getting access to the communication channels or smart meters.

\(\left( \text {Prior load}\right)\) Prior load is that control center makes a series of wrong decisions which acts on the load after receiving the change of biased load.

\(\left( \text {Abnormal region}\right)\) Abnormal region is the region in which prior load is isolated.

In order to detect and isolate the biased load, in which the communication channel is attacked directly by an attacker, we need to find the relationship of the power change among biased load, prior load and generator in abnormal region. The relationship will be specified in detail in the following isolation algorithm. Based on the attack characteristics of FDI attacks, we first need to detect and isolate the abnormal region, and consider the input term \(Bu\left( t\right) \in \mathbb {R} ^{3n+m}\) as the unknown abnormal signals from the wrong instructions of the control center. Then the abnormal region that is subject to the wrong instructions of the control center can be written as

where \(C\in \mathbb {R} ^{\left( 3n+m\right) \times \left( 3n+m\right) }\), and \(y\left( t\right) = \left[ y_{1}\left( t\right) ,...,y_{3n+m}\left( t\right) \right] ^{T}\) is the output vector. Hence, we let the attack term \(Bu\left( t\right)\) as \(B=e_{l_{B}}\), where \(e_{l_{B}}\in \mathbb {R} ^{3n+m}\) denotes the unit indicator vector, \(l_{B}\) is one of the term of the system state \(i_{0}\in \left\{ 1,...,3n+m\right\}\), and \(\left[ e_{l_{B}}\right] _{i_{0}}=1\) when \(l_{B}=i_{0}\), and \(\left[ e_{l_{B}}\right] _{i_{0}}=0\) otherwise. And \(u\left( t\right) =\beta \left( t-T_{Bu}\right) \psi \left( t-T_{Bu}\right)\) where \(\beta \left( t-T_{Bu}\right)\), \(\psi \left( t-T_{Bu}\right)\) and \(T_{Bu}\) are, respectively, the time profile, the unknown bias that is related to the wrong instructions from the control center, and the unknown moment when the stealth attack occurs. The time profile of the attack is modeled as \(\beta \left( t-T_{Bu}\right) =0\) if \(t<T_{Bu}\) and \(\beta \left( t-T_{Bu}\right) =1\) if \(t\ge T_{Bu}\).

Remark 2

The attacker may compromise field devices (smart meters, RTUs) or communication channels (via man-in-the-middle attacks) to inject false data. The adversary possesses knowledge of system topology and parameters but remains unaware of our specific detection mechanisms and adaptive thresholds. While the attacker can read/modify measurement data from compromised nodes, they cannot alter system topology or directly access control center algorithms.

Remark 3

In our work, the primary contribution focuses on developing a novel detection and localization method for bias-based FDI attacks in12,30, rather than on the attack mechanisms themselves. Consequently, we adopted a simplified attack model involving direct measurement injection to clearly demonstrate the core capabilities of our proposed detection framework. This approach aligns with common practices in the initial stages of detection methodology development, where the focus is on validating the fundamental concept against well-established attack models. However, we fully acknowledge the reviewer’s valid point that this abstraction limits the realism of attack scenarios. The omission of protocol-specific vulnerabilities (e.g., in DNP3, IEC 61850, GOOSE) and packet-level effects does represent a limitation in evaluating the practical applicability of our method.

Remark 4

Adversaries conducting reconnaissance (TA0043) gather grid topology and parameter knowledge through open-source intelligence or network sniffing, subsequently gaining initial access (TA0101) via compromised field devices such as smart meters and RTUs or through communication interception techniques like man-in-the-middle attacks. During the collection phase (TA0099), attackers harvest legitimate measurement data to craft stealthy attack vectors, which ultimately enable impact (TA0104) through false data injection that manipulates state estimation–potentially causing operational disruptions or market manipulation. Furthermore, our proposed defense mechanism aligns with the NIST Cybersecurity Framework’s Detect function (Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, Recover) by employing an observer-based detection approach specifically designed to enhance threat visibility in industrial control systems.

The division of regional

Ideally, we aim to detect and isolate Bu(t). However, in large-scale power systems, real-time measurement of every output value may be infeasible. Instead, we assume the smart grid can be partitioned into N coherent areas. Each area \(\sum ^{(I)}\), where \(I \in {1, \dots , N}\), contains disjoint sets of generators and buses. Connections within each area are determined based on clustering. Under these premises, we introduce the following definition.

Definition 2

(Cluster35) A cluster in the network \(G=\left( \nu ,\varepsilon \right)\) is a group \(\nu ^{\left( I\right) }=\left\{ \nu _{1}^{\left( I\right) },...,\nu _{k_{I}}^{\left( I\right) }\right\} \subseteq \nu\) of \(k_{I}\le \left| \nu \right|\) nodes such that the following criteria are both satisfied.

C1: Cluster connectivity: for each pair of nodes \(\nu _{i}^{\left( I\right) }\), \(\nu _{j}^{\left( I\right) }\) in \(\nu ^{\left( I\right) }\), there exists at least one path connecting them entirely composed by elements of the same cluster;

C2: Stable margin: for each group \(\nu ^{\left( I\right) }\), it must hold that a stable power margin assessment system.

In other words, if two nodes are not connected or exhibit dissimilar power margins, they are considered not to satisfy the clustering criteria and are therefore assigned to different clusters. Then the I-th subsystem \(\sum \nolimits ^{\left( I\right) }\) is described by

where we assume the nonlinear subsystem \(\sum \nolimits ^{\left( I\right) }\) comprised of \(n_{I}\) generators and \(n_{I}+m_{I}\) buses, and \(n_{I}\le n\), \(\left( n_{I}+m_{I}\right) \le\) \(\left( n+m\right)\). \(E^{\left( I\right) }\), \(A^{\left( I\right) }\in \mathbb {R} ^{\left( 3n_{I}+m_{I}\right) \times \left( 3n_{I}+m_{I}\right) }\), and \(\phi ^{\left( I\right) }\left( x\right)\), \(P^{\left( I\right) }\left( t\right)\) , \(B^{\left( I\right) }u^{\left( I\right) }\left( t\right) \in \mathbb {R} ^{3n_{I}+m_{I}}\), where \(B^{\left( I\right) }=e_{l_{B}^{\left( I\right) }}^{\left( I\right) }\in \mathbb {R} ^{3n_{I}+m_{I}}\) denotes the unit indicator vector, \(l_{B}^{\left( I\right) }\) is one of the term of the system state \(i_{0}^{\left( I\right) }\in \left\{ 1,...,3n_{I}+m_{I}\right\}\), \(\left[ e_{l_{B}^{\left( I\right) }}^{\left( I\right) }\right] _{i_{0}^{\left( I\right) }}=1\) when \(l_{B}^{\left( I\right) }=i_{0}^{\left( I\right) }\), and \(\left[ e_{l_{B}^{\left( I\right) }}^{\left( I\right) }\right] _{i_{0}^{\left( I\right) }}=0\) otherwise. Then the output of the subsystem \(\sum \nolimits ^{\left( I\right) }\) can be written as

where \(C^{\left( I\right) }\in \mathbb {R} ^{\left( 3n_{I}+m_{I}\right) \times \left( 3n_{I}+m_{I}\right) }\) and \(y^{\left( I\right) }\left( t\right) \in \mathbb {R} ^{3n_{I}+m_{I}}\).

Although the large scale power system may be already decomposed into smaller subsystems, \(\sum \nolimits ^{\left( I\right) }\) may still consist of a large number of generators and buses. It still makes the detection and especially the isolation of cyber attacks very difficult. Hence, we present following division algorithm to further decompose subsystem \(\sum \nolimits ^{\left( I\right) }\) into smaller groups. This partitioning enables the creation of dedicated isolation modules for each group, thereby facilitating the isolation of abnormal regions containing unknown attack signals originating from incorrect control center instructions. The division algorithm is described as follows.

The design is realized by decomposing \(\sum \nolimits ^{\left( I\right) }\) into \(n_{I}\) groups, where each group contains one generator and some buses. The connections within a group are dense while the connections between groups are sparse. And then the q-th group is denoted by \(S^{\left( I,q\right) }\), \(q\in \left\{ 1,...,n_{I}\right\}\). These groups may be disjoint or overlapping, and constitute a combined set \(M^{\left( I\right) }\) comprised of \(k_{s}^{\left( I\right) }\) groups \(s\in \left\{ 1,...,2^{n_{I}}-1\right\}\), e.g., if the group \(\left( S^{\left( I,q\right) }:q\in \left\{ 1,2\right\} \right)\), then we can combine set \(M^{\left( I\right) }\) comprised of \(k_{s}^{\left( I\right) }\), \(s\in \left\{ 1,2,3\right\}\), e.g., \(k_{s}^{\left( I\right) }\in \left\{ \left( S^{\left( I,1\right) }\right) ,\left( S^{\left( I,2\right) }\right) ,\left( S^{\left( I,1\right) },S^{\left( I,2\right) }\right) \right\}\). Then we select stable and observable groups from \(k_{s}^{\left( I\right) }\) denoted as \(J^{\left( I\right) }\). We create matrix \(F^{\left( I\right) }\) of dimensions card \(\left( J^{\left( I\right) }\right) \times \left( k_{s}^{\left( I\right) }\right)\), the j-th row corresponds to the j-th element of \(J^{\left( I\right) }\), denoted as \(J^{\left( I\right) }\left\{ j\right\}\), \(j\le 2^{n_{I}}-1\), the p-th column corresponds to the p -th element of \(k_{s}^{\left( I\right) }\), denoted as \(k_{s}^{\left( I\right) }\left\{ p\right\}\), \(p\in \left\{ 1,...,2^{n_{I}}-1\right\}\), if \(J^{\left( I\right) }\left\{ j\right\} \cap k_{s}^{\left( I\right) }\left\{ p\right\} \ne \emptyset\), then \(F_{jp}^{\left( I\right) }=1\), else \(F_{jp}^{\left( I\right) }=0\). Let \(\nu _{o}^{\left( I\right) }\) denote the number of distinct columns of \(F^{\left( I\right) }\), and \(\mu _{o}^{\left( I\right) }\) denote the maximum number of mutually identical columns of \(F^{\left( I\right) }\), then eliminate the row of matrix \(F^{\left( I\right) }\) only when \(\nu _{o}^{\left( I\right) }\) and \(\mu _{o}^{\left( I\right) }\) are not changed after eliminating any row, now the matrix \(F^{\left( I\right) }\) can be denoted as \(F^{*\left( I\right) }\), the row of \(F^{*\left( I\right) }\) is denoted as \(J_{o}^{\left( I\right) }\), therefore matrix \(F^{*\left( I\right) }\) is of dimensions card \(\left( J_{o}^{\left( I\right) }\right) \times \left( k_{s}^{\left( I\right) }\right)\). The decomposition procedure is shown in Algorithm 1.

Then \(J_{o}^{\left( I\right) }\) is the smaller group by decomposing subsystem \(\sum \nolimits ^{\left( I\right) }\). Next step is the design of group \(J_{o}^{\left( I\right) }\). The proposed general strategy for designing \(J_{o}^{\left( I\right) }\) is described next, we consider that the \(\kappa\)-th group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) is characterized by

where \(x^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) is made up of the dynamic of the \(\kappa\)-th group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\), and \(y^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) represents a column vector made up of the output element for the \(\kappa\)-th group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\).

Detection of false data injection Attack

In this section, we present the method to detect the abnormal region affected by the wrong instructions from the control center subject to the stealth attack. First, we design the observer \(N^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) to monitor the group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\). Then, the adaptive thresholds are computed by considering system uncertainty. Based on the comparison of the residual and the adaptive threshold, we judge the occurrence of the stealth attack in this system.

Observer-based residual generation

Considering the system \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\), the estimation model is based on the nonlinear observer as follows

where \(\hat{x}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) is the estimation of \(x^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) and \(L^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) is the observer gain matrix. The objective of this work is to find out the abnormal region affected by the unknown stealth attacks under the following assumptions:

Assumption 1

For each subsystem \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\), the state vector \(x^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) and the input vector \(P^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) generated by a feedback controller denoted by \(C_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\), remain bounded before and after the occurrence of unknown attack.

Assumption 2

The nonlinear model \(\phi ^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( x\right)\) in (9) is said to satisfy a locally Lipschitz condition, and the parameter \(\gamma ^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) denotes the Lipschitz constant for all \(t\ge 0\) such that \(\left\| \phi ^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( x\right) -\phi ^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( \hat{x} \right) \right\| \le \gamma ^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left\| x-\hat{ x}\right\|\).

Assumption 1 and Assumption 2 are standard in attack detection of nonlinear interconnected systems.

Remark 5

The Lipschitz constants \(\gamma ^{(I,\kappa )}\) are not estimated online but are calculated a priori for each defined region I and a set of representative operating points \(\kappa\). This is achieved by numerically bounding the norm of the Jacobian of the nonlinear function over the expected operational domain of each region, defined by practical constraints on voltage magnitudes and phase angle differences. The adaptive threshold logic utilizes this pre-computed set of constants, selecting the value of \(\gamma ^{(I,\kappa )}\) most appropriate for the current estimated operating condition of the system, thereby ensuring robust performance without the need for online recalculation of the observer gains.

Let us define \(e^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) =x^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) -\hat{x}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) as the state estimation error, and under healthy condition, it is uniformly bounded and satisfies \(\left| e^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) \right| \le \overline{e^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }(t)}\) , where \(\overline{e^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }(t)}\) is defined in the following remark.

Remark 6

The observer used in this work is based on the structure observability of Lipschitz nonlinear systems, which is used to observe the states of the subgroups. In the absence of malicious false data injection attacks in the systems, the state estimation under the healthy condition, denoted by \(\hat{x }_{H}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\), satisfies

Let us define \(\overline{e^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }(t)}=x^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) -\hat{x}_{H}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) and \(\overline{r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) }=C^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\overline{e^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) }\) as the state estimation error and the residual under healthy condition, respectively.

Then taking (9) and (10) into account, we obtain

Theorem 1

If the observer gain \(L^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) is chosen such that matrix \(\left( A^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }-L^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }C^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\right)\) is Hurwitz stable, then \(\left| r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) \right| \le \overline{ r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) }\) at all times \(t\in \mathbb {R} \ge 0\) if \(u^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) =0\) at all times \(t\in \mathbb {R} \ge 0\), moreover, in the absence of the attacks, the residual \(\overline{ r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) }\) is stable. Moreover the observer gain \(L^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) can be defined

Proof

Taking the conditions described in Theorem 1 into account, we show that system (12) is uniformly bounded, i.e., \(r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) \le \overline{r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) }\) at all times \(t\in \mathbb {R} \ge 0\) if \(u^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) =0\) at all times \(t\in \mathbb {R} \ge 0\) since the state vector \(x^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) and the input vector \(P^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) generated by the feedback controller \(C_{0}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) remain bounded, in the absence of the attack in the group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\), the residual \(\overline{r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) }\) is stable, where \(\overline{e^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) }\) is defined as stable. It follows that the triple \(\left( E^{\left( I,\kappa \right) },A^{\left( I,\kappa \right) },C^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\right)\) is observable, so that \(L^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) can be chosen to make the pair \(\left( E^{\left( I,\kappa \right) },A^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }-L^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }C^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\right)\) Hurwitz. A Lyapunov function for the system is

We have

Therefore the observer (12) is stable. \(\square\)

Remark 7

From In eq. (13), one can obtain \(\left( {A^{{\left( {I,\kappa } \right)}} - L^{{\left( {I,\kappa } \right)}} C^{{\left( {I,\kappa } \right)}} } \right)^{T} P^{{\left( {I,\kappa } \right)}}\)\(+ P^{{\left( {I,\kappa } \right)T}} \left( {A^{{\left( {I,\kappa } \right)}} - L^{{\left( {I,\kappa } \right)}} C^{{\left( {I,\kappa } \right)}} } \right) + \gamma ^{{\left( {I,\kappa } \right)2}} P^{{\left( {I,\kappa } \right)2T}} P^{{\left( {I,\kappa } \right)}} + I < 0\) . Thus, the In eq. (15) becomes less than equal to 0. Namely, the proposed state observer is stable

Computation of adaptive thresholds

The adaptive threshold denoted by \(\theta ^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) in group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\), is designed to bound the residual where the attack is not injected to this smart grid system. In this section, based on the structure of adaptive threshold for network36,37,38, we compute threshold from two parts: the part of threshold \(\theta _{1}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) related to the residual under healthy condition in group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) and the another part of threshold \(\theta _{2}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) related to various kinds of uncertainties in the group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\). At first, we consider the part of threshold \(\theta _{1}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) as follows

where \(\overline{r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }(t)}\) is defined in Remark 7, denoting the residual under healthy condition in group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\).

Then, we consider the another part of threshold \(\theta _{2}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\). The group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) model (9) under various kinds of uncertainties and not subject to the attack can be expressed as

where \(\Delta g^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( y^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) ,r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }(t),\vartheta \right)\) represents various kinds of model uncertainties including three parts: \(\left. 1\right)\) the error existing in the process of formulating the dynamic model in the group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\), \(\left. 2\right)\) the inevitably error existing in observation process, and \(\left. 3\right)\) the noise \(\vartheta\) including dynamic model process formulation noise and observation process noise. Without loss of generality, we assume that \(\Delta g^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( y^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) ,r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }(t),\vartheta \right)\) is linear and bounded39 as follows

where \(T_{1}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left\| y^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) \right\| _{2}\) is related to the error of the dynamic model formulation in the group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\), \(T_{2}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left\| r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) \right\| _{2}\) is related to the error of observation process in the group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\), and \(T_{3}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) represents the noise which is uniform distribution in the running process of in the group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\).

The residual equation (12) can be rewritten as

Obviously, the complex domain output produced by \(\Delta g^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( y^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) ,r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }(t),\vartheta \right)\) can be expressed as

where s denotes the Laplace operator.

Then the threshold \(\theta _{2}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) is obtained based on the model uncertainties as follows

where

where \(G=\left( j\omega E^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }-A^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }+L^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }C^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\right) ^{-1}\).

Then, the complete threshold \(\theta ^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) of the group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) can be expressed as

Remark 8

The supremum over frequency in Eq. (23) is not computed online at each time step, as this would be computationally intractable for a large-scale system. Instead, the \(\mathcal {H}\infty\) norm \(\Gamma ^{(I,\kappa )} =\underset{{\omega \ge 0}}{\sup }V(\cdot )\) is a constant property of the observer’s error dynamics for a given region I and operating point \(\kappa\). It is pre-computed offline during the observer design phase using standard numerical tools (e.g., solving a Hamiltonian eigenvalue problem). Computational tractability for real-time application is thus guaranteed because the online calculation of the adaptive threshold \(\theta ^{(I,\kappa )}(t)\) reduces to a simple, efficient algebraic operation: \(\theta ^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }=\overline{r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }(t)}+\Gamma ^{(I,\kappa )}\left( T_{1}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left\| y^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) \right\| _{2}\right. \left. +T_{2}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left\| r^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) \right\| _{2}+T_{3}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\right)\) This involves only pre-stored constants and the norms of real-time measurements, ensuring minimal computational overhead. The adaptivity stems from the time-varying signals |y(t)| and |r(t)|, not from online recomputation of the supremum.

Remark 9

To effectively mitigate false alarms arising from model inaccuracies and measurement noise, advanced attack detection systems implement sophisticated robustness strategies that go beyond simple fixed thresholds. These include adaptive thresholds that dynamically adjust to operating conditions, statistical evaluation of residual sequences to quantify the likelihood of faults versus noise, and temporal filtering to confirm persistent deviations. Moreover, the underlying observers are often designed using robust methodologies such as robust observer structures, which explicitly decouple residuals from modeled uncertainties and disturbances. This integrated approach ensures that alarms are triggered primarily by significant and consistent fault signatures, rather than by inherent system noise or modeling imperfections, substantially enhancing detection reliability.

If the residual of every group in the system is smaller than its adaptive threshold, it is no abnormal signal, i.e., the system is not subject to cyber attacks and the control center do not execute the wrong instructions to the group. The decision is made that the abnormal signal from the control center occurs as long as at least one of the groups residual exceeds its adaptive threshold. In other words, by comparing with the adaptive threshold, the residual of the observer can detect the unknown abnormal signal injected in to the groups. The judgment criteria are given as follows

Based on (24), we can detect the unknown abnormal signal in the group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\), and further prepare for the isolation of cyber attack in next section.

Isolation of false data injection attack

On detecting stealth attack in the group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\), this cyber attack isolation procedure in the combined set \(M^{\left( I\right) }\) is presented for isolating the abnormal region affected by the wrong instructions from the control center attacked by the stealth attack. Based on the power change of this abnormal region, we present the decision algorithm to isolate the biased load and prior load.

Isolation of abnormal region

The cyber attack isolation procedure in \(M^{\left( I\right) }\) is initiated for isolating the abnormal region \(k_{s}^{\left( I,p\right) }\) that has been affected by abnormal signal, where \(p\in \left\{ 1,...,2^{n_{I}}-1\right\}\) denotes the p-th region of \(k_{s}^{\left( I\right) }\). The isolation decision is obtained by consistency test about the theoretical model and the observed pattern. The observed pattern is based on the actually observer values. Then the abnormal region can be isolated when the observed pattern and the theoretical model satisfy the consistency test.

We firstly define the logic judgment matrix, denoted by \(F^{*\left( I\right) }\), \(I\in \left\{ 1,...,N\right\}\), obtained from Algorithm 1. The matrix \(F^{*\left( I\right) }\) is binary, consisting of \(J_{o}^{\left( I\right) }\left\{ \kappa \right\}\) rows, \(\kappa \in \left\{ 1,...,N_{C_{I}}\right\}\) and \(k_{s}^{\left( I\right) }\left\{ p\right\}\) columns, \(p\in \left\{ 1,...,2^{n_{I}}-1\right\}\), while every column corresponds to a different combined set \(M^{\left( I\right) }\), the theoretical pattern of the p-th combination \(F_{p}^{*\left( I\right) }\) is defined as

where we assume that one abnormal signal represents the change in the output of the abnormal region if and only if the abnormal signal is in this region. Therefore, \(F_{\kappa p}^{*\left( I\right) }=1\) which indicates that the \(\kappa\)-th group \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\) can detect the abnormal signal if at least one abnormal signal belongs to the aAbnormal region \(k_{s}^{\left( I,p\right) }\), and \(F_{\kappa p}^{*\left( I\right) }=0\) otherwise.

Then, the observed pattern suffered by abnormal signal in \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\), \(\kappa \in \left\{ 1,...,N_{C_{I}}\right\}\), denoted by \(D^{\left( I\right) }\left( t\right)\), can be described as follows.

where \(D^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\), \(\kappa \in \left\{ 1,...,N_{C_{I}}\right\}\) is defined by the designed observer and the adaptive threshold in \(J_{o}^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\). \(D^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) =1\) if the agent residual is bigger than the adaptive threshold, i.e., there is at least one of abnormal signal, and \(D^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) =0\) otherwise.

The attack isolation judgement logic is based on the consistency test. If consistency test is satisfied, \(D^{\left( I,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) =F_{\kappa p}^{*\left( I\right) }\) for \(\kappa \in \left\{ 1,...,N_{C_{I}}\right\}\). Then the region \(k_{s}^{\left( I,p\right) }\) corresponding to the p-th column \(k_{s}^{\left( I\right) }\left\{ p\right\}\) is the abnormal region.

Remark 10

The robustness of the logic judgment matrix \(F^{*\left( I\right) }\) in identifying compromised regions under simultaneous multi-region attacks fundamentally depends on the preliminary results generated by robust observers and adaptive thresholds. Robust observers minimize the influence of model uncertainties and noise on residuals, ensuring that even under multiple concurrent attacks, the residuals retain meaningful information about true anomalies. Adaptive thresholds further enhance discrimination by dynamically adjusting to operational conditions, preventing false alarms due to noise or expected uncertainties. However, while \(F^{*\left( I\right) }\) can theoretically isolate unique fault signatures under ideal conditions, its effectiveness is significantly compromised against coordinated False Data Injection (FDI) attacks, where adversaries exploit system knowledge to create stealthy or ambiguous residual patterns that evade detection or induce misidentification. Practical limitations also include residual masking, nonlinear observer degradation, and inherent model inaccuracies. Therefore, \(F^{*\left( I\right) }\)should not be used in isolation but must be integrated with robust observer-based anomaly detection—to improve overall resilience and ensure reliable attack localization under multi-region threats.

Isolation of biased load and prior load

Attackers compromise communication channels in the power system and directly target the biased load. Although the actual dynamics of the biased load remain unchanged, its measurements are manipulated, leading to incorrect load power data being sent to the control center. As a result, after a series of decision-making processes, the control center executes erroneous control commands. This, in turn, adversely affects the load power of the prior load. Therefore, this section focuses on isolating both the biased load and the prior load. However, in the physical layer of the smart grid, only the power of the prior load is actually altered. As a result, the power output of the generators in the abnormal region may deviate significantly from the actual aggregate demand. To meet the true power demand, the generator output must therefore be adjusted. To isolate the biased load and the prior load, we propose first considering key measurements that reflect changes in generator power within the abnormal region. Meanwhile, in this region, the prior load changes in the same manner as the generator. Since the control center may require up to a second to make decisions, this time window can be used to identify which biased load exhibits the same deviation as the load signal received from the control center. The proposed isolation procedure is summarized in Algorithm 2.

Based on Algorithm 2, the prior load and the biased load can be isolated by analyzing the relationship between generator power and load power within the abnormal region. Thereby, stealth attacks in the power system can be effectively detected and isolated.

Discussion

While the proposed detection framework demonstrates promising performance in offline simulations, its practical implementation requires careful consideration of computational feasibility, latency constraints, and integration with existing grid control infrastructure. In terms of computational demand, the adaptive observers are based on linear matrix operations and recursive updates, which are inherently efficient and suitable for near-real-time execution. However, scalability to very large systems may require further optimization or distributed implementation across multiple processing units. Regarding latency, the algorithm operates at the same timescale as state estimation–typically every few seconds in current SCADA systems and potentially at sub-second rates with PMU-based monitoring. The additional latency introduced by our method is primarily due to the residual evaluation and threshold adaptation steps, which involve limited arithmetic operations. Initial testing suggests this adds minimal delay, but precise quantification will require deployment on embedded platforms or control center hardware.

For integration, the framework can be implemented as a standalone application within the control center environment, receiving measurement data from the state estimator and outputting alarms and localization information to the operator. Compatibility with common utility data formats (e.g., CIM, IEC 61850) and protocols (e.g., DNP3, IEC 104) would be essential. Alternatively, it could be embedded as an additional module in modern EMS software suites. Future work will focus on porting the algorithm to an industrial PC or grid simulator (e.g., OPAL-RT) to rigorously evaluate real-time performance and interoperability under realistic communication and data environments. This will provide concrete data on throughput, latency, and reliability needed for practical deployment.

In practical power grid security applications, the computational complexity of the overall attack detection and localization algorithm is dominated by the robust observer-based state estimation process, which scales cubically with the number of buses in the system, expressed as \(\mathcal {O}(m_{I}^{3})\). This is because the core operation—solving the estimation problem using \(H_{\infty }\) filters or unknown input observers—requires maintaining and updating covariance matrices and solving Riccati equations, whose size is proportional to the system states (primarily voltage magnitudes and angles), which themselves scale linearly with the number of buses. For a large interconnected grid like the Eastern Interconnection in the U.S. (comprising over 50,000 buses), this cubic relationship makes robust estimation computationally intensive, often requiring high-performance computing resources or optimized algorithms. The subsequent evaluation of residuals against adaptive thresholds and the application of the logic matrix \(F^{*(I)}\) for localization add only a linear cost \(\mathcal {O}(N \cdot m_{I})\), which is negligible compared to the observer computation. Therefore, the feasibility of real-time or near-real-time security assessment for large grids hinges almost entirely on the efficiency of the robust observer implementation, making research into decentralized, parallelized, or approximate methods critical for scaling these protection systems.

Simulation results

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm for detecting and isolating stealth attacks, a simulation is conducted using the IEEE 18-generator 37-bus smart grid system shown in Fig. 2. Following Algorithm 1, the grid is partitioned into 6 coherent areas based on the sparsity of the connection topology and the stability of power margins. In this example, the following stealth attack scenarios are simulated:

-

(1)

the measurement output of Bus 3 is directly compromised by an attacker starting at \(t = 3~\text {sec}\) (Case 1),

-

(2)

the measurement output of Bus 35 is directly compromised by an attacker starting at \(t = 5~\text {sec}\) (Case 2).

Case 1: the attack injected to bus 3

In this case, an attack is launched directly on Bus 3 in the smart grid system at \(t=\)3 \(\sec\). The power measurement output in the communication channel is altered with a bias of +20kw. As a result, the control center receives incorrect data and erroneously estimates that the total power demand exceeds the actual value, leading to a corresponding 20kw reduction in the power margin. The control center then makes a decision based on this faulty evaluation–a process that takes approximately 1 \(\sec\). Consequently, the power output at Bus 5 is affected at at \(t=\)4 \(\sec\) due to the erroneous control instruction, resulting in a 20kw decrease. Although the actual load power at Bus 3 remains unchanged, the generator power in Area 1 (monitored via Bus 5) is reduced by 20kw. This discrepancy leads to energy wastage. We systematically analyze the power margin using data acquired and managed by the smart grid control center. The power margin profile of the 6-area grid system is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Only the margin of Area 1 is found the abnormal change. Therefore, stealth attack detection and isolation algorithm is run in Area 1. As shown in Fig. 4,

Area 1 comprises 3 generators and 7 buses. To detect cyber attacks and isolate the biased load and prior load, we partition Area 1 into three connected groups according to Algorithm 1. The grouping is defined as follows: generator \(G_{1}\) along with buses 1 and 2 form Group 1; generator \(G_{2}\) and buses 3 and 4 constitute Group 2; and generator \(G_{3}\) together with buses 5, 6, and 7 belong to Group 3. Meanwhile, we assume that the structure of Group 1 is unobservable. Therefore, the detection and isolation algorithm is executed based on this group. Firstly we construct set \(M^{\left( 1\right) }\) by disjoint or overlapping group 1, 2 and 3 applying Algorithm 1 , i.e., the construct set of all possiple combinations is \(k_{s}^{\left( 1\right) }=\left\{ 1,2,3,\left( 1,2\right) ,\left( 1,3\right) ,\left( 2,3\right) ,\left( 1,2,3\right) \right\}\). Then we exclude the combinations, where the group 1 denotes as \(J^{\left( 1\right) }=\left\{ 2,3,\left( 1,2\right) ,\left( 1,3\right) ,\left( 2,3\right) ,\left( 1,2,3\right) \right\}\) does not ensure the observability (Table 1). Next, we create matrix \(F^{\left( 1\right) }\)

described in Algorithm 1, as shown in Table 4. The number of distinct columns of \(F^{\left( 1\right) }\) is 6, while the maximum number of mutually identical columns is 2. Applying steps 5−15 of Algorithm 1, we create matrix \(F^{*\left( 1\right) }\)

based on the matrix \(F^{\left( 1\right) }\), as shown in Table 2. \(J_{o}^{\left( 1\right) }=\left\{ 2,3,\left( 1,2\right) ,\left( 1,3\right) \right\}\), and the number of this group is \(\kappa =4\). Denote \(J_{o}^{\left( 1,1\right) }\), \(J_{o}^{\left( 1,2\right) }\), \(J_{o}^{\left( 1,3\right) }\), and \(J_{o}^{\left( 1,4\right) }\) to be the Region 2, Region 3, Region \(\left( 1,2\right)\), and Region \(\left( 1,3\right)\), respectively.

Then we design observer \(N^{\left( 1,\kappa \right) }\) to monitor the group \(J_{o}^{\left( 1,\kappa \right) }\) as described in Section III, and provide the estimation model based on (10). We now consider a numerical realization of 4 regions respectively, while

\(E^{\left( 1,1\right) }=diag\left( 1,0.125,0,0\right)\),

\(E^{\left( 1,2\right) }=diag\left( 1,0.034,0,0,0\right)\),

\(E^{\left( 1,3\right) }=diag\left( 1,1,0.16,0.293,0,0,0,0\right)\),

\(E^{\left( 1,4\right) }=diag\left( 1,1,0.235,0.13,0,0,0,0,0\right)\),

\(A^{\left( 1,1\right) }=\left[ \begin{array}{cccc} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & -0.125 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right]\),

\(A^{\left( 1,2\right) }=\left[ \begin{array}{ccccc} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & -0.068 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right]\),

\(A^{\left( 1,3\right) }=\left[ \begin{array}{cccccccc} 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -0.048 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1.113 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right]\),

\(A^{\left( 1,4\right) }=\left[ \begin{array}{ccccccccc} 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -0.346 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -0.143 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right]\),

\(C^{\left( 1,1\right) }=I_{4}\), \(C^{\left( 1,2\right) }=I_{5}\), \(C^{\left( 1,3\right) }=I_{8}\), \(C^{\left( 1,4\right) }=I_{9}\), \(\gamma ^{\left( 1,1\right) }=2.31\), \(\gamma ^{\left( 1,2\right) }=1.65\), \(\gamma ^{\left( 1,3\right) }=3.27\), \(\gamma ^{\left( 1,4\right) }=2.92\), \(L^{\left( 1,1\right) }=2.5\), \(L^{\left( 1,2\right) }=1.7\), \(L^{\left( 1,3\right) }=3.53\), and \(L^{\left( 1,4\right) }=3.07\) by (13). For the computation of adaptive thresholds, we use the following parameters: \(T_{1}^{\left( 1,1\right) }=0.6\), \(T_{2}^{\left( 1,1\right) }=0.3\), and \(T_{3}^{\left( 1,1\right) }\) chosen randomly from 0 to 0.3 in Region 2; \(T_{1}^{\left( 1,2\right) }=0.37\), \(T_{2}^{\left( 1,2\right) }=0.3\), and \(T_{3}^{\left( 1,2\right) }\) chosen randomly from 0 to 0.3 in Region 3; \(T_{1}^{\left( 1,3\right) }=0.53\), \(T_{2}^{\left( 1,3\right) }=0.5\), and \(T_{3}^{\left( 1,3\right) }\) chosen randomly from 0 to 0.3 in Region \(\left( 1,2\right)\); \(T_{1}^{\left( 1,4\right) }=0.49\), \(T_{2}^{\left( 1,4\right) }=0.41\), and \(T_{3}^{\left( 1,4\right) }\) chosen randomly from 0 to 0.3 in Region \(\left( 1,3\right)\). Then, considering \(\overline{r^{\left( 1,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) }\) under no attack, and the system residuals under the attack are shown in Fig. 5.

The residual and adaptive threshold following the attack inject to the region 3: (a) The residual of the rotor angle in region \(\left( 2\right)\) without abnormal signal, (b) The residual of the rotor angle in region \(\left( 3\right)\) with the abnormal signal, (c) The residual of the rotor angle 1 in region \(\left( 1,2\right)\) without abnormal signal, (d) The residual of the rotor angle 2 in region \(\left( 1,2\right)\) without abnormal signal, (e) The residual of the rotor angle 1 in region \(\left( 1,3\right)\) with the abnormal signal, (f) The residual of the rotor angle 2 in region \(\left( 1,3\right)\) with the abnormal signal.

Figure 5a–f portray the decision making process for the group \(J_{o}^{\left( 1\right) }\). Every subfigure presents the temporal evolution of the magnitude of the residual \(r^{\left( 1,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) (blue real line) and the adaptive threshold \(\theta ^{\left( 1,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) (red dash line). As shown in Fig. 5b and f, the abnormal signal can be detected in \(J_{o}^{\left( 1,2\right) }=\left\{ \left( 3\right) \right\}\) and \(J_{o}^{\left( 1,4\right) }=\left\{ \left( 1,3\right) \right\}\), because the residual are bigger than the adaptive thresholds, and the residuals in \(J_{o}^{\left( 1,1\right) }=\left\{ 2\right\}\) and \(J_{o}^{\left( 1,3\right) }=\left\{ \left( 1,2\right) \right\}\) are smaller than the adaptive thresholds as shown in Fig. 5a, c and d. Based on (26), we can also obtain the observed pattern \(D^{\left( 1\right) }\left( t\right) =\left[ 0,1,0,1 \right] ^{T}\) for \(t\in \left[ 4,12\right)\) sec. Then it can be compared to the columns of the logic judgment matrix \(F^{*\left( 1\right) }\), shown in Table 2, and eventually the region \(k_{s}^{\left( 1,3\right) }=\left\{ 3\right\}\) can be detected and isolated as the abnormal region.

Through the above analysis and according to Algorithm 2, the biased load and prior load can be isolated based on changes in generator power within the abnormal region. In this example, smart meters measure variations in both load and generator power, and the resulting data are transmitted to the control center. The load management function of the control center is considered in this process.

Figure 6 portrays the power change of generator \(G_{3}\). From \(t=\)4 \(\sec\), the power has been reduced about 20kw. We can see clearly the change of buses 1-7 from Fig. 7 and from \(t=\)4 \(\sec\), the power of bus 5 has been reduced about 20kw. Therefore, we can isolate that the prior load is bus 5. Then we can see the power of bus 3 is increased about 20kw from \(t=\)3 \(\sec\) , while the abnormal signal does not be detected by the observer in the group 2, where the bus 3 is located. Therefore we can isolate that the biased load is bus 3.

Case 2: the attack injected to bus 35

In this section, we consider a different situation that bus 35 is induced directly by the stealth attack in this smart grid at \(t=\)5 \(\sec\). The power measurement output from the communication channel is biased -30kw. Then the control center receiving the incorrect data and considering the overall power demand is lower than its actual demand, therefore the power margin is increased by 30kw accordingly. As a result, the control center make the decision, and the process will last for 1 \(\sec\). Therefore, the power of bus 37 is increased 30kw at \(t=\)6 \(\sec\). In fact, the actual load power of the bus 35 does not change, and generator power is overloaded 30kw in Area 6 which obtains from bus 37. As a result, the system instability is caused. We analyze power margin systematically through the data acquisition and management from the control center in operation of the smart grid, and from the power margin of 6-area system as shown in Fig. 12,we can see only the margin of area 6 shows abnormal change. Therefore, we will run cyber attack detection and isolation algorithm in area 6 (Fig. 8).

Area 6 consists of 3 generators and 6 buses as shown in Fig. 9.

In order to detect the cyber attack and isolate the Biased load and Prior load, we divide the region 6 into 3 connected groups based on Algorithm 1, i.e., generator \(G_{16}\) and buses 32 and 33 belong to group 1, generator \(G_{17}\) and buses 34 and 35 belong to group 2, and generator \(G_{18}\) and buses 36 and 37 belong to group 3. Meanwhile, we assume that the structure of group 3 is unobservable. Therefore, based on this group the detection and isolation algorithm is running. Firstly, we construct set \(M^{\left( 6\right) }\) by disjoint or overlapping group 1, 2, 3 applying Algorithm 1, i.e., the construction set of all possible combinations is \(k_{s}^{\left( 6\right) }=\left\{ 1,2,3,\left( 1,2\right) ,\left( 1,3\right) ,\left( 2,3\right) ,\left( 1,2,3\right) \right\}\). Then, we exclude the combinations, where the group 3 denotes as \(J^{\left( 6\right) }=\left\{ 1,2,\left( 1,2\right) ,\left( 1,3\right) ,\left( 2,3\right) ,\left( 1,2,3\right) \right\}\) does not ensure the observability (Table 3). Next, we construct matrix \(F^{\left( 6\right) }\)

as described in Algorithm 1, as shown in Table 4. The number of distinct columns of \(F^{\left( 6\right) }\) is 6, and the maximum number of mutually identical columns is 2. Applying steps 5−15 of Algorithm 1, we create matrix \(F^{*\left( 6\right) }\)

based on the matrix F , as shown in Table 4. \(J_{o}^{\left( 6\right) }=\left\{ 1,2,\left( 1,3\right) ,\left( 2,3\right) \right\}\), and the number of this group is \(\kappa =4\). Denote \(J_{o}^{\left( 6,1\right) }\), \(J_{o}^{\left( 6,2\right) }\) , \(J_{o}^{\left( 6,3\right) }\), and \(J_{o}^{\left( 6,4\right) }\) as the Region 1, Region 2, Region \(\left( 1,3\right)\), and Region \(\left( 2,3\right)\), respectively.

Next, we design observer \(N^{\left( 6,\kappa \right) }\) to monitor the group \(J_{o}^{\left( 6,\kappa \right) }\) as described in Section III, and provide the estimation model based on (10). We now consider a numerical realization of 4 regions respectively, while

\(E^{\left( 6,1\right) }=diag\left( 1,1.14,0,0\right)\),

\(E^{\left( 6,2\right) }=diag\left( 1,1.37,0,0\right)\),

\(E^{\left( 6,3\right) }=diag\left( 1,1,0.66,0.54,0,0,0,0\right)\),

\(E^{\left( 6,4\right) }=diag\left( 1,1,0.59,0.92,0,0,0,0\right)\),

\(A^{\left( 6,1\right) }=\left[ \begin{array}{cccc} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & -0.58 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right]\),

\(A^{\left( 6,2\right) }=\left[ \begin{array}{cccc} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & -0.62 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right]\),

\(A^{\left( 6,3\right) }=\left[ \begin{array}{cccccccc} 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -0.53 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -0.653 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right]\),

\(A^{\left( 6,4\right) }=\left[ \begin{array}{cccccccc} 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -0.39 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -0.47 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right]\),

\(C^{\left( 6,1\right) }=I_{4}\), \(C^{\left( 6,2\right) }=I_{4}\), \(C^{\left( 6,3\right) }=I_{8}\), \(C^{\left( 6,4\right) }=I_{8}\), \(\gamma ^{\left( 6,1\right) }=5.33\), \(\gamma ^{\left( 6,2\right) }=4.37\), \(\gamma ^{\left( 6,3\right) }=7.75\), \(\gamma ^{\left( 6,4\right) }=6.25\), \(L^{\left( 6,1\right) }=5.92\), \(L^{\left( 6,2\right) }=4.74\), \(L^{\left( 6,3\right) }=8.21\), and \(L^{\left( 6,4\right) }=6.64\) by (13). For the computation of adaptive thresholds, we use the following parameters: \(T_{1}^{\left( 6,1\right) }=0.65\), \(T_{2}^{\left( 6,1\right) }=0.57\), and \(T_{3}^{\left( 6,1\right) }\) chosen randomly from 0 to 0.3 in Region 1; \(T_{1}^{\left( 6,2\right) }=0.59\), \(T_{2}^{\left( 6,2\right) }=0.3\), and \(T_{3}^{\left( 6,2\right) }\) chosen randomly from 0 to 0.3 in Region 2; \(T_{1}^{\left( 6,3\right) }=0.62\), \(T_{2}^{\left( 6,3\right) }=0.6\), and \(T_{3}^{\left( 6,3\right) }\) chosen randomly from 0 to 0.3 in Region \(\left( 1,3\right)\); \(T_{1}^{\left( 6,4\right) }=0.59\), \(T_{2}^{\left( 6,4\right) }=0.54\), and \(T_{3}^{\left( 6,4\right) }\) chosen randomly from 0 to 0.3 in Region \(\left( 2,3\right)\). Then consider \(\overline{r^{\left( 6,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right) }\) under no attack, and the system residuals under the attack are shown in Fig. 10,

The residual and adaptive threshold following the attack in the region 3: (a) The residual of the rotor angle in region \(\left( 1\right)\) without abnormal signal, (b) The residual of the rotor angle in region \(\left( 2\right)\) without the abnormal signal, (c) The residual of the rotor angle 1 in region \(\left( 1,3\right)\) with the abnormal signal, (d) The residual of the rotor angle 2 in region \(\left( 1,3\right)\) with the abnormal signal, (e) The residual of the rotor angle 1 in region \(\left( 2,3\right)\) with the abnormal signal, (f) The residual of the rotor angle 2 in region \(\left( 2,3\right)\) with the abnormal signal.

Figure 10a–f portray the decision making process for the group \(J_{o}^{\left( 6\right) }\). Every subfigure presents the temporal evolution of the magnitude of the residual \(r^{\left( 6,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) (blue real line) and the adaptive threshold \(\theta ^{\left( 6,\kappa \right) }\left( t\right)\) (red dash line). As shown in Fig. 10d and f, the abnormal signal can be detected in \(J_{o}^{\left( 6,3\right) }=\left\{ \left( 1,3\right) \right\}\) and \(J_{o}^{\left( 6,4\right) }=\left\{ \left( 2,3\right) \right\}\), because the residual are bigger than the adaptive thresholds, and the residuals in \(J_{o}^{\left( 6,1\right) }=\left\{ 1\right\}\) and \(J_{o}^{\left( 6,2\right) }=\left\{ 2\right\}\) are smaller than the adaptive thresholds as shown in Fig. 10a and b. Based on (26), we can also obtain the observed pattern \(D^{\left( 6\right) }\left( t\right) =\left[ 0,0,1,1\right] ^{T}\) for \(t\in \left[ 6,12\right)\) sec. Then it can be compared to the columns of the logic judgment matrix \(F^{*\left( 6\right) }\), shown in Table 4, and eventually the region \(k_{s}^{\left( 6,3\right) }=\left\{ 3\right\}\) can be detected and isolated as the abnormal region.

Then, we can isolate the biased load and prior load based on the change of generator power in the abnormal region according to the Algorithm 2. In this example, smart meters measure the change of load and generator power, and the measurement results are sent to the control center. We consider the load management function of the control center Fig. 11.

Portrays the power change of generator \(G_{18}\). From \(t=\)6 \(\sec\) the power have been increased about 30kw. We can see clearly the change of buses 32-37 from Fig. 12 that from \(t=\)6 \(\sec\), the power of bus 37 have been increased about 30kw. Therefore, we can isolate that the prior load is bus 37. And we can isolate that the biased load is bus 35 because the power of bus 35 is reduced about 30kw from \(t=\)5 \(\sec\), while the abnormal signal does not be detected by the observer in the group 2, where the bus 35 is located.

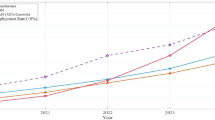

Case 3: Detection performance analysis

To rigorously and comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed framework in detecting and mitigating cyber-attacks on power systems, we meticulously designed and executed a series of 1000 simulated cyber-attacks within the MATLAB/Simulink simulation testing environment on the widely recognized IEEE-37-bus power system. MATLAB/Simulink was chosen for its powerful capabilities in modeling complex power system dynamics and its extensive library of pre-built components, which facilitated the accurate and realistic simulation of the power system under attack scenarios. In each of these simulated attacks, we strategically injected false data that corresponded precisely to \(5\%\) of the nominal voltage amplitude at various buses within the system. This specific percentage was chosen to represent a realistic and challenging attack scenario that could potentially evade traditional detection mechanisms, thereby providing a rigorous test for our proposed framework.

To benchmark the performance of our proposed methodology, we conducted a thorough comparison against three well-established and widely cited FDIA detection approaches. The first approach is based on Extended Kalman Filter (EKF)-based dynamic state estimation in32. The second approach employs Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF)-based dynamic state estimation in33. The third approach involves short-term state prediction techniques in30. To ensure a fair and unbiased comparison, we subjected all four methods (including our proposed framework) to the same set of 1000 simulated cyber-attacks within the MATLAB/Simulink environment and recorded their detection rates, false alarm rates, and overall performance metrics. The comparative analysis of the detection capabilities across these methods is systematically and comprehensively presented in Table 5, which includes detailed statistics on the number of successful detections, missed attacks, and false alarms for each method. This table provides a clear and concise overview of the relative strengths and weaknesses of each approach, enabling researchers and practitioners to make informed decisions about which method is best suited for their specific application and threat environment within the MATLAB/Simulink simulation framework (Table 5).

Experimental results demonstrate the proposed approach achieves a 95.6% detection rate on the IEEE-37-bus testbed, as validated in Table 5. This outcome represents a 1.6% absolute improvement over the next-best performing baseline. In addition, the False Positive Rate under the proposed method can be improved 0.2%. In a sum, compared with detection works, the proposed detection method can enhance the detection performance by introducing the adaptive detection threshold.

Conclusion and future works

This paper proposes an attack detection and isolation framework for large-scale smart grids. First, based on sparsity patterns and stability margins, the large-scale power system is decomposed into smaller grid areas to reduce the complexity of attack detection. In vulnerable areas, an observer-based algorithm is designed to detect abnormal signals. The isolation of abnormal regions is achieved through a consistency test between the logic judgment matrix and the observed behavior patterns. Furthermore, the prior load and biased load are isolated using a proposed algorithm that leverages the relationship between generator and load power. Simulation results demonstrate the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed methodology.

In the future, the following works will be considered: Detection and localization of hybrid attacks, such as denial of service attacks and FDI attacks;elastic response and self-healing capability of the power grid under attack. in addition, the design of hybrid attacks considering the protocol-specific vulnerabilities (e.g., in DNP3, IEC 61850, GOOSE) and packet-level effects.

Data Availability

The data analysed during the current study are included in this article.

References

Sahu, A. et al. Design of next-generation cyber-physical energy management systems: monitoring to mitigation. IEEE Open Access J. Power Energy 10, 151–163 (2023).

Pham, N. H. et al. Real-time cyber-physical power system testbed for optimal power flow study using co-simulation framework. IEEE Access 12, 150914–150929 (2024).

Wang, Y., Chen, C.-F., Kong, P.-Y., Li, H. & Wen, Q. A cyber-physical-social perspective on future smart distribution systems. Proc. IEEE 111(7), 694–724 (2023).

Liu, Y., Ştefanov, A., Semertzis, I. & Palensky, P. GraphCCI: Critical components identification for enhancing security of cyber-physical power systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2, 340–349 (2024).

Rajkumar, V. S., Ştefanov, A., Presekal, A., Palensky, P. & Torres, J. L. R. Cyber attacks on power grids: Causes and propagation of cascading failures. IEEE Access 11, 103154–103176 (2023).

Vu, L., Nguyen, T.-L., Abdelrahman, M. S., Vu, T. & Mohammed, O. A. A cyber-HIL for investigating control systems in ship cyber physical systems under communication issues and cyber attacks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 60(2), 2142–2152 (2024).

Li, Z. S., Wu, G., Cassandro, R. & Wang, H. A review of resilience metrics and modeling methods for cyber-physical power systems (CPPS). IEEE Trans. Reliabil. 73(1), 59–66 (2024).

Iranpour, M. & Narimani, M. R. Analyzing the impact of AC false data injection attacks on power system operation. IEEE Texas Power and Energy Conference (TPEC). College Stat. TX, USA 2025, 1–6 (2025).

Ye, J. & Yu, X. Detection and estimation of false data injection attacks for load frequency control systems. J. Modern Power Syst. Clean Energy 10(4), 861–870 (2022).

Asadi, Y., Farsangi, M. M., Amani, A. M., Bijami, E. & Alhelou, H. H. Data-driven automatic generation control of interconnected power grids subject to deception attacks. IEEE Int. Things J. 10(9), 7591–7600 (2023).

Pasqualetti, F., Dorfler, F. & Bullo, F. Attack detection and identification in cyber-physical networks - part I: Models and fundamental limitations. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 58(11), 2715–2729 (2013).

Forystek, M. & Syrmakesis, A. D., et al. Exploring the Effects of Load Altering Attacks on Load Frequency Control through Python and RTDS, (2025), arXiv:2504.08951, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.08951.

Du, M., Wang, L. & Zhou, Y. High-stealth false data attacks on overloading multiple lines in power systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 14(2), 1321–1324 (2023).

Narang, J. K. & Bag, B. A stealth false data attack on state estimation with minimal network information. In: 2024 Third international conference on power, control and computing technologies (ICPC2T), Raipur, India, pp. 630-635 (2024)

Syrmakesis, Andrew D. & Hatziargyriou, Nikos D. Cyber resilience methods for smart grids against false data injection attacks: categorization, review and future directions. Front. Smart Grids 3, 1–12 (2024).

Syrmakesis, A.-D. A hybrid framework for the cyber resilience enhancement of frequency control in smart grids. Natl. Techn. Univ. (2024). https://doi.org/10.12681/eadd/57208.

Avadh Pati, A. & Adhikary, N. Detection and mitigation against false data injection attacks using SHT and ANN in distributed control of DC microgrid. Elect. Power Syst. Res. 241, 111356 (2025).

Wang, X. et al. Data-driven-based detection and localization framework against false data injection attacks in DC microgrids. IEEE Int. Things J. 12(17), 36079–36093 (2025).

Syrmakesis, A. D., Alcaraz, C. & Hatziargyriou, N. D. DAR-LFC: A data-driven attack recovery mechanism for load frequency control. Int. J. Crit. Infrastr. Prot. 45, 100678 (2024).

Wang, X., Hu, M., Luo, X. & Guan, X. A detection model for false data injection attacks in smart grids based on graph spatial features using temporal convolutional neural networks. Elect. Power Syst. Res. 238, 111126 (2025).

An, Haopeng et al. Cluster partition-fuzzy broad learning-based fast detection and localization framework for false data injection attack in smart distribution networks. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 40, 101534 (2024).

Xin, L., He, G. & Long, Z. Stealthy false data injection attacks detection and classification in cyber-physical systems using deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 22, 141–153 (2025).

Hallaji, E., Razavi-Far, R., Wang, M., Saif, M. & Fardanesh, B. A Stream Learning Approach for Real-Time Identification of False Data Injection Attacks in Cyber-Physical Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forens Sec. 17, 3934–3945 (2022).

Syrmakesis, A. D., Alhelou, H. H. & Hatziargyriou, N. D. A novel cyber resilience method for frequency control in power systems considering nonlinearities and practical challenges. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 60(2), 2176–2190 (2024).

Du, D. et al. A review on cybersecurity analysis, attack detection, and attack defense methods in cyber-physical power systems. J. Modern Power Syst. Clean Energy 11(3), 727–743 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Modeling and detection of false data injection attacks in cyber-physical distribution system with load aggregator interaction. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 40, 10245 (2024).

Zhang, G. et al. Joint detection and localization of false data injection attacks in smart grids: An enhanced state estimation approach. Comput. Elect. Eng. 120, 109834 (2024).

Syrmakesis, A. D., Alhelou, H. H. & Hatziargyriou, N. D. Novel SMO-based detection and isolation of false data injection attacks against frequency control systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 39(1), 1434–1446 (2024).

Yan, J.-J., Yang, G.-H. & Wang, Y. Dynamic reduced-order observer-based detection of false data injection attacks with application to smart grid systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 18(10), 6712–6722 (2022).

Wang, X. Y., Luo, X. Y., Pan, S. Y. & Guan, X. P. Detection and location of bias load injection attack in smart grid via robust adaptive observer. IEEE Syst. J. 14(3), 4454–4465 (2020).

Syrmakesis, A. D., Alcaraz, C. & Hatziargyriou, N. D. Classifying resilience approaches for protecting smart grids against cyber threats. Int. J. Inf. Sec. 21, 1189–1210 (2022).

Kurt, M. N., Yilmaz, Y. & Wang, X. D. Real-time detection of hybrid and stealthy cyber-attacks in smart grid. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics. Secur. 14(2), 498–513 (2019).

Sargolzaei, K., Abbaspour, A., Crane, I. D. & Dixon, W. E. Detection and mitigation of false data injection attacks in networked control systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 16(6), 4281–92 (2020).

Ekram, H., Poor, H. V. & Han, Z. Smart grid communications and networking. Cambridge University Press, (2012).

Reppa, V., Polycarpou, M. M. & Panayiotou, C. G. “ Distributed fault detection in sensor networks via clustering and consensus” in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Osaka, Japan, Dec. 15-18 (2015).

Kerrache, C.A., Lakas, A. & Lagraa, N. “ Detection of intelligent malicious and selfish nodes in VANET using threshold adaptive control” in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Electronic Devices, Systems and Applications (ICEDSA), Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates, Dec. 6-8 (2016).

Chae, Y., Katenka, N. & Dipippo, L. Adaptive Threshold Selection for Trust-Based Detection Systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), Barcelona, Spain, Dec. 12-15 (2016).

Chellal, A., Boughanem, M. & Dousset, B. Multi-criterion Real Time Tweet Summarization Based upon Adaptive Threshold. In Proceedings of IEEE/WIC/ACM Conference on Web Intelligence (WI), NE, USA, Oct. 13-16 (2016).

Akhrif, O. et al. Application of a multivariable feedback linearization scheme for rotor angle stability and voltage regulation of power systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 14(2), 620–628 (1999).

Funding

This work is supported by2023-2024 Cangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Plan Self-Funded Projects(23244101021).

Funded by Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department (ZC2023092).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chengbin Gao: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing. Xue Yu: Writing - original draft, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Formal analysis. Chengbin Gao , Yao Du, Bo Gao, Danyang Tian: Writing - Review & Editing, Methodology. Tiantian Hou: Supervision, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions