Abstract

The efficient operations of orbital satellite constellations, especially those engaged in the dynamic missions, require propulsion systems capable of continuously performing maneuvers. These maneuvers include not only the orbit phasing, the altitude alterations and the attitude control, but also collision-avoidance, satellites rendezvous and deorbiting maneuvers. These maneuvers require the generation of thrust in multiple directions. The thrust-vectoring capability can be achieved by changing the spacecraft orientation beforehand. However, this approach may lead to inefficient propellant management. Another approach to control the thrust vector direction is the use of propulsion systems with in-built thrust-vectoring capability. One of such propulsion systems is the thruster with close ring-shaped gas discharge chamber providing capability to generate thrust in two and more directions. Such geometry of the gas discharge chamber requires the thorough studies. In this work, the starting modes of the thruster with closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber utilizing krypton and argon are studied. It has been established that the presence of a toroidal magnetic field decreases the ignition thresholds of radiofrequency discharge by 32.4%. It is found that the power consumption for the discharge ignition in the multichannel gas discharge chamber depends significantly on the magnetic field strength. In addition, under certain configurations of the externally-applied magnetic field, a decrease in the discharge ignition thresholds is observed due to the hypothesis of the magnetized electrons circulation in-and-out of the gas discharge chamber.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The space industry is currently undergoing a major evolution, driven by growing interest in the practical use of the Earth orbits and the inner space natural objects’ orbits—for example, the Moon and the Mars for providing the communication services on their surfaces. The demands placed on spacecraft are increasing in order to realize ambitious commercial and scientific space missions. This has led to a change in the way spacecraft can be controlled and consequently to a change in the requirements placed on their propulsion systems (PSs). Whereas in the past the only task of the PSs was to move the spacecraft from the reference orbit to the target orbit1, the increased need for precise positioning of the spacecraft, for example, when building orbital constellations, now requires the PSs to drastically increase the satellites maneuverability2,3,4,5. In many respects, the efficiency and longevity of the PSs ensure the active life of the satellite, as these two parameters allow it to successfully perform the functions assigned to it, which are inextricably linked to maintaining its own position, maintaining the orientation of the solar panels, changing the parameters of its orbit, maintaining a certain position of the antennas, etc., which is impossible without the operation of the PSs. Because of these requirements, electric propulsion systems (EP) are now more and more used onboard spacecraft as the long-lasting systems providing the capability of changing the thrust characteristics in a wide range6.

In order to perform the orbital maneuvers and attitude corrections mentioned above, it is necessary to generate thrust in multiple directions7. It is possible to generate thrust in multiple directions with a single thruster head of PSs by changing the satellite orientation beforehand using the attitude control system. However, this method requires additional unfavorable propellant use. More promising approach is the option of using multiple thrusters, but this approach increases the mass of the PSs, reduces the mass of the spacecraft’s payload, and may not be applicable for the implementation onboard small satellites. The most promising solution to this problem is the thrust-vectoring capability (TVC) realized within a single thruster head.

TVC within a single thruster head is well known for chemical rocket engines8,9, but has not been sufficiently investigated in the field of EP10. There are known ways to implement TVC in the most common types of plasma thrusters—Hall-effect and ion thrusters—for example, using a system of sectioned electrodes11,12,13. There are multiple schemes proposed for other types of EP that are in operation or are achieved the high level of maturity14,15,16,17,18,19. However, they have a number of limitations related to their application, the engineering realization and the performance.

One of the most promising technologies for achieving TVC within a single thruster head is the use of electrodeless plasma thrusters (EPTs)7,17,20,21. EPTs have a number of advantages over other types of EP, including the capability to modifying the thrust characteristics in a wide range of parameters22 and the reduced number of elements, which reduces manufacturing and operating costs and increases the reliability of space missions22. However, the complexity of the processes occurring at the plasma generation and acceleration stages in EPTs may result in the problems with the accurate control of thrust characteristics and their predictability during ground testing and space operation17. According to recent data, the efficiency of EPTs is approaching 30%23.

Known methods of TVC in EPT include the use of three cylindrical gas discharge chambers open at both ends, allowing thrust to be generated in six or more directions7,17. There is also known bi-directional electrodeless plasma thruster (BDEPT) tested in space22. Other known flight-tested EPT with TVC uses variable geometry of the externally-applied magnetic field at the exhaust region. These EPTs with TVC are relatively compact comparing them with the other types of EP of the same power- and dimensions-classes and can be used as a basis for the development of more advanced PSs for small spacecraft, in order to increase their maneuverability, the possibility of varying the thrust characteristics according to the operations performed and the operational efficiency of space missions.

However, the schemes of TVC realization in EPTs discussed cannot provide the capability of generating propulsive forces to cover all the directions and moments that can be required for the high maneuverability of a satellite. assume the use of cylindrical gas discharge chambers, the practical application of which in such devices is fairly well studied. There is a theoretical concept which implies the use of a multichannel gas discharge chamber of closed ring-shaped geometry to create a multidirectional PS based on the EPT24. The practical use of multichannel gas discharge chambers of complex geometry as plasma sources in EP is an unexplored and promising area, which leads to the need for experimental studies to determine the further prospects of this technology. The present work is devoted to the experimental study of the ignition thresholds of the radiofrequency (RF) discharge in the externally-applied magnetic field in the closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber of a multichannel electrodeless plasma source (MCEPS) used as the plasma generating and accelerating part of a multidirectional electrodeless plasma thruster (MDEPT).

Experimental setup

Multichannel electrodeless plasma source

The key feature of the investigated MCEPS is the use of the closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber proposed in work by Shumeiko et al.24. Such a special geometry of the gas discharge chamber and its multiple opening at each open end of which having the magnetic nozzles that can be represented by the electromagnets can allow to select the directions of generating the propulsive forces (see Fig. 1). Thus, MCEPS is capable of generating a space-oriented thrust vector at the direction of interest for the mission operator using a single device onboard the satellite.

The design of the MCEPS is fundamentally similar to existing solutions for the realization of the conventional electrodeless plasma sources. The MCEPS consists of a closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber, an inductor a system of toroidal magnetic field magnets, multiple open-ended tubes attached to the gas discharge chamber at one end and at the other opened to the surroundings, and the magnetic nozzles located at the end of the tubes opened to the surroundings. Plasma formation in the gas discharge chamber is achieved by RF discharge ignition and sustaining—mainly by the generation of azimuthal eddy electric fields under the influence of the external radio-frequency magnetic field of the inductor but there are some other secondary fields that can play its role in the processes of the plasma generation and sustaining. The electromagnetic system that surrounds the gas discharge chamber is designed to generate a toroidal magnetic field in the inner cavity of the gas discharge chamber in order to reduce the electron diffusion rate in the direction perpendicular to the direction of the magnetic field lines, i.e. towards the walls of the gas discharge chamber, and to allow the continuous propagation of the waves occurring in the plasma bulk under the influence of the electromagnetic field generated by the inductor and the externally-applied static magnetic field.

Scheme of experimental MCEPS design: 1—propellant inlet, 2—plasma source openings, 3—toroidal magnetic field electromagnets, 4—inductor. Toroidal electromagnets are represented schematically. Arrow in inner cavity of gas discharge chamber indicates one of directions of toroidal magnetic field lines. Magnetic nozzles are not shown.

Multidirectional electrodeless plasma thruster

The MCEPS that is shown in Fig. 1 is the main element of the plasma generation and acceleration segment of the MDEPT investigated. The design of the MDEPT used in this work is shown in Fig. 2. The MDEPT consists of the plasma acceleration and generation section and the control board that includes the electronics. The propellant storage and supply system (PSSS) is not an integral part of this device in the current experiments, but is an external independent system. The MDEPT accelerator section consists of a MCEPS and iris diaphragms combined with magnetic nozzles mounted at the ends of the gas discharge chamber multiple channels. The peak magnetic field strength at the axis of the closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber generated by the toroidal field electromagnets at \(\:{I}_{tor}\) = 5 A is about 15 mT. The peak magnetic field strength at the center of each of the magnetic nozzles’ electromagnets at \(\:{I}_{coil}\) = 5 A is approximately 13 mT. The diaphragms are used to vary the exhaust orifice diameter of in a wide range of values, similar to the approached used in work25. The diaphragms are controlled by transmitting the torque from three servos through gears. It should be noted that in this work the brushless type of servos is used in order to avoid the desorption of oil vapors inside the vacuum chamber. The control board is hidden in the MDEPT mounting plate and is designed to control the iris diaphragms by means of specialized software installed on a computer and described in more detail in26. The dimensions of the MDEPT studied are 1U, corresponding to 100 mm in each of the three dimensions. It should be noted that the PSSS is represented by a separate independent element in these experiments but in the further work is planned to be integrated with the MDEPT, initially, as the 1U block to develop the 2U-sized propulsion system with the capability of generating propulsive forces minimum in three directions.

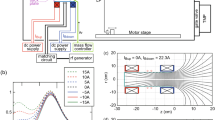

Experimental facility

The schematic diagram of the experimental setup to determine the ignition thresholds of a radiofrequency discharge in an externally-applied static magnetic field in the closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber is shown in Fig. 3. The test bench is constituted by several systems: the vacuum chamber, the vacuum pump system, the inductor, and the diaphragm power supply and control system, the PSSS, and the electromagnet power supply system. The vacuum pump system consists of two lines, a pre-vacuum line and a high vacuum line. An ISP-500 C oil-free scroll pump manufactured by “SHI-MADZU Corp., Kyoto, Japan” is used as the pre-vacuum stage. The high vacuum stage is a TMP-1003 M turbomolecular pump manufactured by “ANEST IWATA, Inc., Yokohama, Japan”. Switching between the lines is done by pneumatic gates. The pressure in the vacuum chamber is measured by a CC-10 vacuum gauge manufactured by “Televac, Inc., Miami, FL, USA” and an ACM 300 capacitive manometer manufactured by “Atovac Co., Ltd., Yongin, Republic of Korea”. The inductor is powered and controlled by a CESAR RF power generator by “Advanced Energy Industries, Inc., Denver, CO, USA” with an operating frequency of 13.56 MHz and maximum power output of 1000 W and a Navio Matching network of similar manufacturer. The RF generator, matching network, and the inductor are connected to each other by an RG-213 cable that is 1 m long. The PSSS consists of the tanks with noble gases—argon and krypton, the electromagnetic gas flow regulator RRG-12, and the flow regulator control unit BUIP-1 M. The propellant flow rate is altered in the ranges from 20 to 160 sccm for krypton and from 15 to 240 sccm for argon. Within these ranges of the propellant flow rates, the pressure in the vacuum chamber is registered in the range from 1.33 × 10− 2 to 13.3 Pa during low and high flow rates of the propellant, respectively. The magnetic nozzles and the toroidal magnetic field coils are powered by the external laboratory power supplies. The current in the electromagnets is changed in the range from 0 to 5 A. The discharge ignition that is visually confirmed by the plasma glowing in the gas discharge chamber is observed through the observation windows of the vacuum chamber. In the experiments, parameters such as the current in the inductor, the type of propellant used, the flow rate of the propellant, the current in the toroidal magnetic field coils and the magnetic nozzles’ electromagnets and the polarity of current switching in the magnetic nozzles are varied. It is reported in the previous works27, that changing the geometry and the parameters of the magnetic field strength affects the ignition threshold of radiofrequency discharges in the medium of noble gases, namely, argon and krypton, which are to be investigated in the present work. Figure 4 shows the exterior of the laboratory setup used in current study.

Operating modes

In this research, by the term threshold electric field for discharge initiation or by its derivatives it is implied that at this field the discharge is initiated and is possible to sustain under certain values of pressure in the gas discharge chamber. More specifically, the change in the current supplied to the inductor and the visual observation are used. The threshold value of the current used for the calculation of the threshold electric field is considered that after which the current is drastically change.

Two series of measurements are carried out: to determine the ignition thresholds of radiofrequency discharge in the external toroidal magnetic field in the closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber for two noble gases—namely, argon and krypton—and to conduct the further studies in the elaboration of the previously established theory by Shumeiko et al. on the influence of the hypothesis of electron circulation in the external magnetic fields created by magnetic nozzles during the process of RF discharge ignition before its ignition27.

In the experiments to determine the ignition thresholds of the RF discharge in the presence of a toroidal magnetic field, several modes of operation of the MDEPT are studied as a function of the current \(\:{I}_{tor}\) in the toroidal field electromagnets for different values of the propellant flow rate in the medium of two noble gases—argon and krypton. MDEPT magnetic nozzles are not active in this type of experiments. Two channels of the gas discharge chamber are completely open (1 and 2), while the aperture installed on channel 3 is completely closed. The summary of the MDEPT modes for the series of experiments to determine the ignition thresholds in the presence of the externally-applied toroidal magnetic field in the closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber are given in Table 1.

The experimental part to determine the influence of the electron circulation phenomenon on the ignition of RF discharge in the closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber is a series of discharge ignition experiments depending on the geometry of the fields generated by the magnetic nozzles in the absence of a toroidal magnetic field and on the values of the propellant flow rates utilizing krypton. The visualization of the modes for this experiment is shown in Fig. 5 and described in Table 2. The configuration of the channels’ diaphragms is similar to modes 1.1 and 1.2.

In Fig. 6, the numerical simulation results of pressure inside the gas discharge chamber versus propellant volume flow rates for krypton and argon in the described open-channel configuration are presented. The computational domain corresponds to the ionization region—the intersection point of the inductor’s geometric center with the annular discharge chamber axis. As mentioned earlier, high propellant flow rates cause significant pressure increase in the vacuum chamber (up to 13,3 Pa), which differs from operational conditions of similar plasma thrusters in low Earth orbit. However, studying the characteristics of the proposed thruster at high flow rates is primarily of scientific interest, since such propellant consumption rates still can be of interest onboard small spacecraft for high-thrust modes. At low flow rates, the vacuum chamber conditions can be considered similar to those of comparable plasma thrusters operating in low Earth orbits. Note that the computational domain for the determination of the pressure in the gas discharge chamber corresponds to the ionization region— the intersection point of the inductor’s geometric center with the gas discharge chamber axis.

Results and discussion

Experiments with toroidal magnetic field

In accordance with the methods for obtaining and processing experimental data, for the determination of the values of the threshold azimuthal eddy electric field strength in the inner cavity of the closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber at the moment of the discharge ignition, the values of the current flowing through the inductor are determined for experiments with a toroidal magnetic field. Then, these values of the current are used to calculate the threshold electric field strengths. The results obtained are shown for krypton in Fig. 7 and for argon in Fig. 8.

In Figs. 8 and 9, it is shown that the presence of a toroidal magnetic field to the reduction in the threshold electric field strengths over the whole range of the propellant flow rates studied for both types of noble gases used. The largest reductions in the ignition thresholds compared to the experiments in the absence of the toroidal magnetic field in krypton and argon media are 32.4% (60 sccm, \(\:{I}_{tor}\) = 5 A) and 21.0% (120 sccm, \(\:{I}_{tor}\) = 5 A), respectively. The decrease in the RF discharge ignition thresholds in the presence of the toroidal magnetic field is due to the decrease in the loss rate of the charged particles, namely, electrons, on the walls of the gas discharge chamber, similar to the principle of tokamak operation, which leads to an increase in the number of charged particles in the inner cavity and consequently to the ease of the discharge ignition process.

In order to study this in more detail, the threshold power data at different values of \(\:{I}_{tor}\) for the argon experiments are analyzed. The results were normalized to the peak threshold power value. These normalized results are shown in Fig. 9.

Experimental plot of the normalized discharge threshold power (\(\:{P}_{inductor}/{{P}^{max}\:}_{inductor}\)) versus argon propellant flow rate, parameterized by the current in the toroidal field electromagnets. Maximum power, \(\:{{P}^{max}\:}_{inductor}\), in these series of experiments is 19 W. Measurement errors of \(\:{P}_{inductor}\) and \(\:\dot{m}\) are 2%.

From Fig. 9, it can be concluded that the largest decrease in 60% of the power required for the discharge ignition over the whole range of considered parameters utilizing argon as the propellant is observed at \(\:{I}_{tor}\) = 3 A. For a more detailed study, the total power consumption for the ignition and the sustaining of the discharge in the argon medium, taking into account the energy losses in the electromagnets, is analyzed. The total electrical resistance of the toroidal field electromagnets surrounding the closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber is 0.7 Ohm. Figure 10 shows the total power consumption normalized to its peak value at \(\:{I}_{tor}\) = 0 for different experimental regimes.

From Fig. 10, it can be concluded that the most energy saving mode of the discharge ignition and the sustaining is observed at the current in the toroidal field electromagnets of \(\:{I}_{tor}\) = 1 A. It is noted that the maximum reduction relative to the experiments without a toroidal magnetic field is about 24%. In this mode, the energy consumed for discharge ignition and sustainment across the entire range of argon propellant flow rates is within a range of up to 16 W for the thruster studied. Such low energy consumption suggests the possibility of the device’s practical application onboard small form-factor satellites with low power availability.

It is needed to make an important note. The primary mechanism for the reduction in the threshold electric field for the discharge ignition observed in the current experiments is referred to the decrease in the transverse diffusion of electrons. At the same time, it is acknowledged that the externally-applied static magnetic field may alter the plasma load impedance contributing to the improved efficiency of RF power transfer by affecting the impedance matching conditions of the RF generator-load line. The differentiation of these factors making effects on the threshold electric for the discharge ignition may require further investigation. Nevertheless, in the course of the current investigation their effects can be considered being combined.

Experiments with external magnetic fields of magnetic nozzles

Using the modes for the experiments to determine the influence of the electron circulation phenomenon on the RF discharge ignition threshold presented in Table 2, the discharge ignition processes in the closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber are studied as a function of the geometry of the external magnetic fields generated by magnetic nozzles. Three types of switching polarities of two magnetic nozzles used in these experiments, installed at the open ends of the gas discharge chamber channels are investigated. In two experiments the polarities are the same (modes 2.1 and 2.3), resulting in the collision of two opposite in the direction magnetic fields lines and the generation of two different closed magnetic field circuits with the region of the increased strength in the volume between the magnetic nozzles. In the third experiment (mode 2.2), the polarities are different, leading to the closure of the magnetic field lines and the generation of the common magnetic field in the region between the electromagnets. In the framework of the described experiments, similarly to the experiments with the toroidal magnetic field, the values of the threshold power required for the discharge ignition utilizing krypton as the propellant are determined and the corresponding values of the azimuthal eddy electric field strength on the axis of the gas discharge chamber in the center of the inductor are calculated. The experimental data are shown in Fig. 11.

According to the data obtained, shown in Fig. 11, it can be seen that in the experiments with closing the force lines between the electromagnets, the lowest value of the azimuthal eddy electric field strength, which is necessary for discharge ignition, is observed among the series 2.1–2.3. This phenomenon confirms the theory proposed by Shumeiko27, that is that the electrons are magnetized and can leave the gas discharge chamber through an open end, move along the magnetic field lines and return through another channel into the inner cavity of the gas discharge chamber. This leads to an increase in the number of charged particles, namely, the electrons, in the inner cavity and facilitates the discharge ignition process. It should be noted that the process of the electron circulation is possible only before the discharge is ignited. This method of reducing the discharge ignition threshold can be practically implemented only in the gas discharge chambers of complex configuration, i.e. with several sides of the gas discharge chamber opened to the surroundings. At low propellant flow rates up to 40 sccm utilizing krypton, the presence of any magnetic field lines leads to higher discharge ignition thresholds compared to the experiments without the magnetic field lines. This is due to an additional increase in the free path length of the electrons under the influence of magnetic field lines in an already rarefied medium, which leads to a decrease in the number of electron-atom interactions per unit time and, consequently, to a decrease in the efficiency of the propellant ionization process.

Conclusion

In this work, the ignition thresholds of the radiofrequency discharge in the externally-applied static magnetic field in the closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber are determined. Two series of experiments are conducted: to study the influence of the presence of the toroidal magnetic field on the ignition threshold of the RF discharge, and to conduct the influence of the electron circulation phenomenon in the external magnetic field. During the first series of experiments, it is found that the presence of the toroidal magnetic field at fixed values of the propellant flow rates for both propellants, namely, argon and krypton, leads to the significant reduction in the ignition thresholds of the RF discharge in the closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber. The largest reductions in the discharge ignition thresholds compared to the experiments in without the externally-applied magnetic field and at the current in the toroidal field electromagnets at \(\:{I}_{tor}\) = 5 A in the medium of krypton and argon are 32.4% (60 sccm) and 21.0% (120 sccm), respectively. The decrease in ignition thresholds in the presence of the toroidal magnetic field is due to the decrease in the rate of diffusion of electrons to the walls of the gas discharge chamber in the direction perpendicular to the direction of the magnetic field lines. This leads to the decrease in the rate of reduction of the concentration of charged particles in the inner cavity and, as a consequence, facilitates the process of discharge ignition. It is also found that the greatest decrease in the power ignition thresholds reaches 60% reduction utilizing argon at the current in the toroidal field electromagnets of \(\:{I}_{tor}\) = 3 A and the propellant flow rate of 150 sccm.

In the experiments to determine the influence of the electron circulation phenomenon on the RF discharge ignition thresholds, it is found that the presence of the externally-applied magnetic field generated by the magnetic nozzles, whose magnetic field lines connect to each other outside the open channels of the closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber, also leads to the reduction in the RF discharge ignition thresholds. It should be noted that such a method of reducing discharge ignition thresholds can be practically implemented only in the EPT having the gas discharge chambers of the special configurations such as the MCEPS has.

In addition, the total energy consumption of the multi-channel source studied for the discharge ignition and the sustaining in the presence of the toroidal magnetic field utilizing argon as the propellant is analyzed. The most energy-efficient mode for the plasma source operation under a toroidal magnetic field (considering electromagnet losses) is achieved at \(\:{I}_{tor}\) = 1 A, reducing the power consumption by up to 24% compared to the case without a magnetic field. In this mode, the energy consumed for discharge ignition and sustainment across the entire range of argon propellant flow rates is within a range of up to 16 W. Such a low power consumption allows to consider the possibility of using the MDEPT onboard the satellites of the small form-factor to increase their maneuverability opening novel opportunities for their usage in the dynamic space missions.

A new direction for further investigation in the field of the discharge ignition in the multidirectional electrodeless plasma thrusters involves a comprehensive impedance analysis of the plasma load. This will require a modification of the experimental and theoretical instruments to enable evaluation of the active and reactive components of the antenna-plasma complex impedance while varying the externally-applied static magnetic field.

Methods

Determination of power relationships

In the experiments and data processing, the power in inductor, \(\:{P}_{inductor}\), is considered to be the delivered power from the RF generator. The power in inductor, \(\:{P}_{inductor}\), is used to determine the trends to which the power consumption follows to facilitate the process of transition from using the stationary RF power source to the customized one. For the determination of the power in inductor, the assumption on the negligibility of the wave effects in the short radiofrequency lines comparing to the wavelength is applied. This assumption can be applied in the experiments because the radiofrequency line length used is approximately 22 times shorter than the wavelength corresponding to the current frequency of 13.56 MHz. Even if the wave effects take place in the line between the RF generator and the load—the inductor and the discharge—the terminating impedance can be considered being equal to the line characteristic impedance that is 50 Ohms since the distance between the matching network and the load is negligible in comparison to the wavelength corresponding to the RF current frequency. In the further development of the MDEPT, the RF generator used in the flight tests of the BDEPT and the MTVEPT thrusters will be used implementing which it is possible to not have the distance between the generator output connector. and the inductor22. In light of the assumption made, the power in inductor, \(\:{P}_{inductor}\), is determined as follows:

where \(\:{P}_{forwarded}\) is the power forwarded by the RF generator to the line and the load, \(\:{P}_{reflected}\) is the reflected power, \(\:{P}_{dissipated}\) is the dissipated power.

The dissipated power, \(\:{P}_{dissipated}\), can be described by:

where \(\:{P}_{disline}\) is the power dissipated in the line, \(\:{P}_{dismatch}\) is the power dissipated in the matching network.

The forwarded, \(\:{P}_{forwarded}\), and the reflected, \(\:{P}_{reflected}\), powers are controlled using the RF generator capability to do it.

The power dissipation in the AE Navio Matching network manual, \(\:{P}_{dismatch}\), is up to 1% but not more than 4 W for the used models of the RF generator and the matching network. Thus, it can be described as follows:

For the line based on the cable RG-213 with the whole length of 1 m at the frequency of 13.56 MHz, the power loss will be − 0.02 dB. The corresponding output power, \(\:{P}_{out}\), can be determined as follows:

Expressing from the Eq. (4) the output power, \(\:{P}_{out}\), the following expression can be written:

Then using the forwarded, \(\:{P}_{forwarded}\), and the output, \(\:{P}_{out}\), powers, the power dissipation in the line, \(\:{P}_{disline}\), can be determined as follows:

Using Eqs. (3) and (6), the dissipated power, \(\:{P}_{dissipated}\), can be determined as follows:

Thus, the delivered power can be determined as follows:

The important note is that the thruster is placed inside the vacuum chamber in a way that the inductor is not surrounded by the metal objects to prevent the coupling to the parts of the chamber and, consequently, to prevent power dissipation in regions other than the inner cavity of the gas discharge chamber.

Experimental data obtaining and processing methodologies

In the course of the experimental studies, the values of the power delivered to the inductor and the current flowing through it at the moment of discharge ignition are determined for all the MDEPT operating modes considered. The threshold value of the current used for the calculation of the threshold electric field is considered that after which the current is drastically change. For example, before the discharge ignition, the current was 8 A. If at this value, the current has changed, for example, to 2 A along with the occurrence of the glowing in the gas discharge chamber, the value of 8 A is registered as the threshold current. The fact of discharge ignition is determined visually through the glass observation windows of the vacuum chamber and parametrically by registering the drastic change in the current flowing through the inductor. The preliminary resulting functional dependencies, without any processing of the experimental data, are shown in Fig. 12.

Experimental data before processing. Experimental modes from Table 1. Measurement errors for \(\:{P}_{inductor}\) and \(\:\dot{m}\) are 2%.

During the experiments, it is observed that the value of the current delivered to the inductor changes significantly at the moment of the discharge ignition. This is due to the change in the load characteristics in the inner cavity of the gas discharge chamber due to the occurrence of the charged particles inside the gas discharge chamber. To obtain the data on the threshold electric field strengths, the inductor currents at which the drastic change in the current occurred and at which there is a visually detectible glowing of the discharge in the gas discharge chamber are used for the analysis.

The relationship between the power consumed by the inductor and the corresponding current in the inductor circuit is determined experimentally using a PEM Rogowski monitor from “Power Electronic Measurements Ltd, Long-Eaton, UK” (see Fig. 13).

Based on the available experimental data (see Fig. 13), the obtained values are interpolated. The current in the inductor is measured by the PEM Rogowski monitor. The sixth order polynomial is used as an interpolation curve, which makes it possible to obtain values of adj. R2 ≈ 0.997 acceptable for subsequent analysis. Based on the obtained dependence, it is possible to estimate the inductor current over the entire range of characteristic values of the power delivered to the inductor. The measured error in determining the current from the approximation curve is no more than 5%. The extrapolation of the current values is performed for the power range of 2 to 14 W. For these power range the experimental measurements are omitted because the power vs. current dependence in the range from 14 to 35 W exhibits a straightforwardness without fluctuations.

To determine the azimuthal electric field strength on the axis of the gas discharge chamber corresponding to the breakdown in the gas medium, it is necessary to know the current flowing through the inductor and the inductor characteristics.

The threshold current that is required to ignite the discharge, is used to calculate the values of the azimuthal electric field strength at the moment of discharge ignition. The alternating current applied to the antenna in accordance with Ampere’s law generates an alternating axial magnetic field \(\:{B}_{z}\)21:

where \(\:\omega\:=2\pi\:{f}_{RF}\) is the cyclic frequency of the alternating current flowing through the antenna, \(\:{\mu\:}_{0}=1.26\cdot\:{10}^{-6}\) H/m is the vaccuum permeability, \(\:{I}_{RF0}\) is the amplitude value of the current force, \(\:N\) is the equivalent number of turns of the inductor, \(\:l\) is the length of the inductor21.

To calculate the equivalent number of turns \(\:N\) for the antenna used, the inductance equation for a magnetic inductor of inductance \(\:L\) is used21:

from which the equivalent number of turns can be expressed21:

where \(\:S\) is the cross-sectional area of the inductor. By determining the inductance, the equivalent number of turns \(\:N\) can be estimated.

The measured inductance for a 40 mm long antenna was 17 µHn. According to Faraday’s law and Maxwell’s equations, the axial alternating magnetic field \(\:{B}_{z}\) induces an azimuthal eddy electric field \(\:E\):

where \(\:r\) is the distance from the axis of the gas discharge chamber to the antenna21.

The azimuthal eddy electric field determines the discharge initiation threshold for a given value of magnetic field and propellant flow rate. The distance from the axis of the gas discharge chamber to the antenna is 11 mm. On the basis of expressions (1)–(4) and measured parameters of the inductor, it is possible to estimate the strength of the azimuthal eddy electric field at the moment of discharge ignition.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Choueiri, E. Y. A critical history of electric propulsion: the first 50 years (1906–1956). J. Prop. Power. 20, 193–203. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.9245 (2004).

Pashaev, A. D., Shumeiko, A. I. & Telekh, V. D. Determination of the minimum size of a small spacecraft of the Cubesat standard for the possibility of using modern propulsion systems. AIP Conf. Proc. 2549, 050002. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0107879 (2023).

Rafalskyi, D. et al. In-orbit demonstration of an iodine electric propulsion system. Nature. 599, 411–415. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04015-y (2021).

Liddle, J., Holt, A. P., Jason, S. J., O’Donnell, K. A. & Stevens, E. J. Space science with cubesats and nanosatellites. Nat. Astron. 4, 1026–1030. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-020-01247-2 (2020).

Massey, R., Lucatello, S. & Benvenuti, P. The challenge of satellite megaconstellations. Nat. Astron. 4, 1022–1023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-020-01224-9 (2020).

Lev, D. et al. The technological and commercial expansion of electric propulsion. Acta Astronaut. 159, 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2019.03.058 (2019).

Shumeiko, A. I., Telekh, V. D. & Mayorova, V. I. Development of a novel wave plasma propulsion module with six-directional thrust vectoring capability. Acta Astronaut. 191, 431–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2021.11.028 (2022).

Resta, E., Marsilio, R. & Ferlauto, M. Thrust vectoring of a fixed axisymmetric supersonic nozzle using the shock-vector control method. Fluids. 6, 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids6120441 (2022).

Afridi, S. et al. Techniques of fluidic thrust vectoring in jet engine nozzles: a review. Energies. 16, 5721. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16155721 (2023).

Shumeiko, A., Telekh, V. & Ryzhkov, S. Thrust-vectoring schemes for electric propulsion systems: A review. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 38, 103401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cja.2025.103401 (2025).

Stark, W., Gondol, N. & Tajmar, M. Concept and design of a hall-effect thruster with integrated thrust vector control. J. Electr. Prop. 1, 21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44205-022-00023-w (2022).

Ding, M. et al. Performance and plume characteristics of a Hall-effect thruster with asymmetrical gas supply. Vacuum. 190, 110285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacuum.2021.110285 (2021).

Gozhaya, E., Kudriavtzev, S. & Nikulin, N. SPT thrust vector control. In 34th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, AIAA-1998-3643. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.1998-3643 (AIAA, 1998).

Chen, Z. et al. Plume deflection using an asymmetrical magnetic nozzle for an applied-field magnetoplasmadynamic thruster—an experimental demonstration and numerical analysis. Acta Astronaut. 209, 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2023.04.042 (2023).

Takahashi, K. & Imai, R. Two-dimensional deflection of a plasma plume exhausted from a magnetically steered radiofrequency plasma thruster. Phys. Plasmas. 29, 054501. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0090476 (2022).

Caldarelli, A. et al. Radial characterization of an ion beam in a deflected magnetic nozzle. J. Electr. Prop. 1, 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44205-022-00012-z (2022).

Shumeiko, A. I., Jarrar, F. S. & Swei, S. S. Advanced wave plasma thruster with multiple thrust vectoring capability. In AIAA SCITECH 2022 Forum, 2190AIAA. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2022-2190 (2022).

Merino, M. & Ahedo, E. Contactless steering of a plasma jet with a 3D magnetic nozzle. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 26, 095001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6595/aa8061 (2017).

Merino, M., García-Lahuerta, D. & Ahedo, E. Plasma acceleration in a magnetic arch. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 32 (6), 065005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6595/acd476 (2023).

Vincent, S. P. H. et al. I. A birdcage resonant antenna for Helicon wave generation in TORPEX. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 95 (9), 093505. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0212529 (2024).

Chabert, P. & Braithwaite, N. Physics of Radio-frequency Plasmas (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Shumeiko, A. I., Pashaev, A. D., Savelev, P. O. & Telekh, V. D. In-orbit demonstration of bi-directional electrodeless plasma thruster. Int. Astronaut. Congress. 2024, 358–366. https://doi.org/10.52202/078371-0040 (2024).

Takahashi, K. 30% conversion efficiency from radiofrequency power to thrust energy in a magnetic nozzle plasma thruster. Sci. Rep. 12, 18618. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22789-7 (2022).

Shumeiko, A. I., Jarrar, F. S. & Swei, S. S. M. Electrodeless plasma thruster with closed-ring-shaped gas discharge chamber. U S Patent. 12, 012,234 (2024).

Andronov, A. A. et al. Plume characterization of electrodeless plasma thruster with configurable exhaust. Symmetry 17, 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17050661 (2025).

Shumeiko, A. I. & Telekh, V. D. Direct thrust measurements of 2U-sized bi-directional wave plasma thruster. AIP Adv. 2171, 170019. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0160582 (2023).

Shumeiko, A. I., Telekh, V. D. & Ryzhkov, S. V. Starting modes of bi-directional plasma thruster utilizing Krypton. Symmetry 15, 1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym15091705 (2023).

Funding

This work was performed at large-scale research facility “Beam-M” of Bauman Moscow State Technical University following the government task by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (FSFN-2024-0011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I.S. and A.A.A.; methodology, A.I.S. and A.A.A.; software, A.I.S. and A.A.A.; validation, A.I.S., A.A.A., A.D.P., P.O.S., and V.D.T.; formal analysis, A.I.S. and A.A.A.; investigation, A.I.S. and A.A.A; resources, A.I.S.; data curation, A.I.S. and A.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.I.S. and A.A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.I.S. and A.A.A.; visualization, A.I.S. and A.A.A.; supervision, A.I.S.; project administration, A.I.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shumeiko, A.I., Andronov, A.A., Pashaev, A.D. et al. Starting modes of multidirectional electrodeless plasma thruster with closed ring-shaped gas discharge chamber. Sci Rep 15, 41032 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24995-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24995-5