Abstract

The study aimed to evaluate the potential of incorporating biochar with poultry manure to address the constant challenges of sandy, loam soils due to poor water retention and low soil fertility, and their influence on the growth and yield of Amaranthus cruentus during the Rabi and Kharif seasons. The combined effect of manures on soil health over different seasons was unexplored, so the current research has been taken up to understand the impact of different treatments on physical, chemical, and microbial dynamics in the Rabi and Kharif seasons. Advanced statistical analysis was used to measure the soil and plant factor variations across seasons. Pre- and post-harvest results showed substantial progress in the soil bulk density, water-holding capacity (WHC), and nutrient retention in KR5 (biochar + poultry manure) treatment, where WHC displayed a strong positive correlation with organic matter (r > 0.82). Even chemical analysis indicated increased soil nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and carbon levels. Metagenomic analysis implied microbial diversity and abundance promoting nitrogen fixation and decomposition of organic matter. FTIR and SEM also revealed structural improvements that are beneficial for microbial colonization and nutrient retention. The combination of biochar and poultry manure showed higher growth, increasing plant height by 40 cm and yielding over 550 g/m2 during the Kharif season. The results have revealed that the combination of biochar and poultry manure has improved soil fertility, microbial diversity, and yield of Amaranthus cruentus grown in sandy loam soils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the crucial global challenges in today’s context is the management of agricultural waste, which is associated with environmental effects and complexities in disposal. Improper management of agricultural waste contributes to water pollution from runoff, soil degradation, and greenhouse gas emissions such as nitrous oxide, methane, impairing climate change, and depleting biodiversity1. Recycling agricultural and wood waste not only manages waste disposal but also enhances soil health, decreases nutrient runoff, and improves agricultural resilience2,3,4. Despite these developments, there remained a pointed gap in enhancing these practices for sustainable agricultural productivity. Sandy loam soils are common in many regions, merging the drainage capacity of sandy soils with the nutrient retention of loam soils. Conversely, these soils are extremely vulnerable to deprivation due to insignificant water intrusion, low organic matter, and controlled nutrient retention5,6. These restraints impede microbial activity necessary for nutrient recycling and soil health, while bare sandy loam soils are liable to erosion, intensifying nutrient losses7,8. These adversities are particularly obvious in semi-arid and drought-prone regions, where sustainable management practices are essential for maintaining ecological balance and soil productivity.

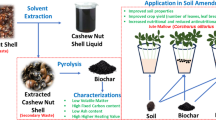

Organic treatments like cow dung, vermicompost, poultry manure, and compost have been mostly utilized to enhance the soil fertility and activity of microorganisms9,10. These materials, however, tend to decompose rapidly and are prone to leaching and volatilization in sandy soils, which diminishes their long-term effectiveness11. This has led to the exploration of more stable soil treatments such as biochar, a carbon-rich material produced through pyrolysis of organic feedstocks under low-oxygen conditions12,13.

Biochar has gained major interest for its versatile application in soil remediation. Previous studies illustrate that adding biochar to soil improves the yields of various crops, like mung beans, soybeans, peas, French beans, and maize14,15,16 . In a study, the application of biochar in Colombian savanna soil notably improved maize yield17. In low-fertility soils, adding biochar has improved bean plants nitrogen fixation14,16,18. The charcoal and compost amendments have exhibited increased recovery of nitrogen compared to mineral fertilization on similar soil types19,20,20. Moreover, biochar application enhanced upland rice yields in low-phosphorus availability sites in northern Laos and Alfisol of Southwest Africa, and improved the response to fertilizer. In the Mediterranean basin, a large volume of biochar applications increased durum wheat biomass and yield by up to 30% over two seasons22,23,24. Despite these promising results, there is a lack of extensive studies investigating the long-term interactions between biochar, organic amendments, and soil microbial communities, particularly in sandy loam soils.

The synergistic utilization of organic treatment, like poultry manure with biochar, has shown the possibility of increasing soil health and crop productivity25, 26. Poultry manure is a nutrient-rich organic amendment that requires critical elements like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium to enhance microbial activity and nutrient availability27. Research indicates that combining poultry manure and biochar amplifies the benefits of both amendments by assisting in nutrient release and improving soil structure21. The past study confirmed that amendments such as palm kernel husk biochar with poultry manure, goat biochar combined with poultry manure, and plantain peel biochar, as a solution combination, could effectively sequester carbon, nitrogen, improve fertilizer efficiency, and improve productivity28. Though the long-term steadiness of these combinations and their effects on crop yield in demanding soil types like sandy loam soils remains unexplored.

Sawdust, a byproduct of the wood industry, raises environmental risks when improperly managed, like air pollution by burning and water contamination through runoff29. Converting sawdust into biochar through pyrolysis mitigates these risks while producing a stable, carbon-rich material with substantial agricultural benefits30. The properties of sawdust biochar, like carbon content, pore structure, and stability, depend on the wood species and processing methods used.

Our study focused on evaluating the impact of Syzygium cumini biochar on the growth, yield, and productivity of Amaranthus cruentus, commonly known as red amaranth. By incorporating Syzygium cumini biochar individually and combining it with poultry manure into the sandy, loam soil, we aimed to assess its influence on soil characteristics and its subsequent effects on the growth parameters of Amaranthus cruentus. To assess the impact of sawdust biochar, as well as a mixture of biochar and poultry manure amendments, on plant growth and yield, a pot experiment was conducted using Amaranthus cruentus as the test plant. Specifically, the study seeks to.

-

1.

Evaluate the combined effect of biochar and poultry manure on the growth and yield of Amaranthus cruentus compared to synthetic fertilizer and unamended soils.

-

2.

Examine the impact of the combination of sawdust biochar and poultry manure-based soil physicochemical characteristics, such as pH, organic carbon content, and nutrient availability.

-

3.

Investigate the impact of biochar and poultry manure on soil microbial biomass and diversity, focusing on their role in improving soil fertility.

Though voluminous work has been carried out on biochar, these studies have overlooked the long-term stability and synergistic effects of the combination with organic treatments. Moreover, these studies are limited to the sandy loam soil, which is vulnerable to nutrient and water deficiency. So, these hypotheses aim to comprehensively evaluate the potential benefits of biochar derived from Syzygium cumini sawdust in combination with poultry manure in improving soil quality and supporting sustainable agricultural practices, addressing a critical research gap in the field.

Materials and methods

Experimental setup and climate details

The study was conducted on sandy loam soil collected from GITAM Universitys farmland, which had not been cultivated for four years. The pot experiments were conducted over two seasons, corresponding to the Rabi and Kharif cropping periods. Specifically, for the Rabi season, seeds were sown in early November 2023, and the harvest was completed by late April 2024. For the Kharif season, seeding commenced in early June 2024 with harvest finalized by mid-October 2024. These timelines align closely with regional agricultural practices.

Soil samples were collected from a depth of 0–20 cm at coordinates 17.7816ºN, 88.3775ºE in 2023. The sandy loam soil, prevalent in most of the region, was chosen due to its moderate water retention, ease of root penetration, and suitability for a wide range of crops, including Amaranthus. The seeds of Amaranthus cruentus were collected from the local market of Visakhapatnam. The Amaranthus crop was selected for its quick adaptability to varied soils and climatic conditions, as well as rapid growth and sensitivity to soil treatments. This might make an ideal indicator crop for assessing treatment effects on soil fertility and plant productivity. The study used a complete block design (CBD) with a factorial arrangement, including three replicates for each treatment combination. The CBD was chosen for its spatial variability within the experimental setup, which is relevant to environmental factors such as light, temperature, and humidity. The collected soil samples were air-dried in the laboratory under shade, following which a 0.2 mm sieve was employed to obtain fine soil to estimate various soil properties. This region, situated at an altitude of 190.29 feet above sea level, receives an average annual rainfall of 755 mm and has a mean temperature of 28.4⁰C. The soil in this farm field is classified as sandy loam. The area experiences a semitropical monsoon climate characterized by a distinct rainfall pattern, temperature, and humidity throughout the year. The average monthly rainfall ranges from a low of approximately 5 mm during the early months of January to April, gradually increasing as the monsoon season approaches, peaking at around 110 mm in September and then tapering off to about 20 mm by November. This pattern reflects the typical monsoon cycle, with significant precipitation concentrated in the middle of the year. In terms of temperature, the region exhibits notable seasonal variations. The mean maximum temperatures range from 28 °C in November to a peak of 40 °C in May. Similarly, the mean minimum temperatures range from a low of 18 °C in November 2023 to a high of 27 °C in May 2024 (Fig. 1). These temperature fluctuations highlight the warm to hot conditions prevalent throughout the year, with the highest temperatures observed just before the onset of the monsoon rains. The relative humidity in the area also shows a moderate range, fluctuating between 55% in April and reaching up to 65% in September. This indicates a generally humid environment, with the highest humidity levels coinciding with the peak of the monsoon season. Overall, the climatic data highlights a typical semitropical monsoon climate, marked by significant rainfall during the mid-year months, high temperatures, and relatively consistent humidity levels.

Preparation for biochar

The sawdust from Syzygium cumini, obtained from a furniture manufacturing warehouse, amounted to 100 kg. The choice was due to its local availability, cost-effectiveness, and high lignocellulosic content. The biochar from Syzygium cumini was produced by first burning the sawdust in a kiln (a type of oven) for 30 min in the absence of oxygen, yielding 1 kg of biochar. Subsequently, pyrolysis was conducted for 100 h at approximately 450 °C31,32. The biochar particles were sieved through a 2 mm sieve for collection. The resulting biochar was analyzed for its contents of carbon (C), nitrogen (N), potassium (K), phosphorus (P), hydrogen (H), and sulphur (S). The procedures for determining organic carbon, moisture content, and water holding capacity followed standard soil analysis methods.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis

The ATR-FTIR Alpha-II model spectrophotometer from Bruker was used for the analysis. The measurements were performed in attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode. About 1 mg of ground sample was placed on the ATR crystal and compressed with a force of 100 N to ensure optimal transmission. Three scans were conducted for each sample, and the spectra were converted to absorbance units before further processing.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis

SEM analysis was conducted using the TESCAN MIRA S6123 device model. The analysis was employed with a magnification of 500X. This technique was utilized to examine the morphological characteristics of both the manures and the soil, providing insights into the topography of the soil samples33. By assessing these features, the SEM analysis offered valuable information about the surface structures and potential interactions of the soil and manure, enhancing the understanding of their physical properties and effects.

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The crystalline phases of treatments KR1 to KR5 were analyzed using a Bruker DB Advance Powder X-Ray Diffractometer S.N.- 216,730). The air-dried samples were finely ground using a mortar and pestle and sieved through a 75-micron mesh to ensure uniform particle size, and the samples were placed onto a sample holder to create a flat, even surface for analysis. The diffractometer was calibrated using a standard reference material, and each sample was scanned, and diffraction patterns were recorded.

Treatment of manures

The seeds were planted in the pot bed after being enriched with manure and fertilizers. The pots were organized in a complete block design with five treatments, where applications were defined as follows: control (no manure treatment – KR1), chemical fertilizer – NPK (urea: 12.98 g, Single Super Phosphate (SSP): 7.1 g, Muriate of Potash (MP): 24.98 g – KR2), biochar (1 kg -KR3), poultry manure (1 kg- KR4), and a combination of biochar and poultry manure (1 kg – KR5). The KR2, KR3, KR4, and KR5 treatments were applied to the soil twice during the experiment. These treatments were applied in two equal doses, half initially incorporated before sowing, and the remaining half applied 30 days after sowing, ensuring sustained nutrient release throughout plant growth. The application rates for biochar and poultry manure in this experiment were determined by the specific pot dimensions, which were 4 inches (10.16 cm) in diameter and 3 inches (7.62 cm) in height. Each pot received 1 kg of material, and when converted to a field equivalent rate, this corresponds to approximately 1234.6 tons per hectare (t/ha) based on a surface area of 0.0081 m2 per pot. This rate is significantly greater than typical field application rates. Biochar is usually applied at 10–30 t/ha and poultry manure at 5–20 t/ha34,35. Such elevated rates are common in pot studies to ensure adequate nutrient availability within the limited soil volume and to facilitate detection of treatment effects under controlled conditions.

Pot experiments have minimal nutrient loss due to small soil volume and enclosure, unlike field conditions, where runoff and leaching reduce nutrient use efficiency and increase environmental impact, necessitating lower, optimized application rates for cost-effective, sustainable field use34,35,36.

Biochar is a carbon-rich material whose effects on methane emissions depend on its type, application rate, and soil environment. Some studies indicate that high biochar rates can stimulate methanogenic microbes in anaerobic soil microsites, increasing methane emissions37. However, biochar can also reduce methane by enhancing soil aeration and supporting methane-consuming microbes[ 37, 38] 14. Poultry manure harbours microorganisms capable of producing methane under anaerobic conditions, but emissions are substantially lower in aerobic soils like sandy loam due to oxygen inhibition of methanogens38,39. Combining biochar and poultry manure with careful rate management can improve nutrient availability while minimizing greenhouse gas emissions34,36.

While the calculated application rates in this pot experiment exceed standard agricultural recommendations, their use is justified within controlled-pot studies designed to mimic improvements achievable in sandy loam soils. Practical field applications require lower, optimized rates to minimize cost, environmental risks, and nutrient loss while maintaining agronomic benefits.

Soil and manure analysis

The soil samples upper layer (0- 20 cm) was collected before being inserted into the pot; the plow layer was a standard depth where most of the microbial activity, root activity, and nutrient cycling occur. Each pot size is about 4 inches wide and 3 inches high; these dimensions were selected to maintain consistency, ensuring uniform soil volume and root zone for all treatments. The physicochemical parameters of the soil and fertilizers were analyzed meticulously. Soil particle composition was determined by weight, with soil samples passed through a series of sieves with varying aperture sizes to classify sand (0.02–2.0 mm), silt (0.002–0.02 mm), and clay (< 0.002 mm). Bulk density was measured using a specialized metal core sampling cylinder of known volume. Soil moisture content was calculated gravimetrically by drying the soil samples to a constant weight, following the method by Misra40. Soil pH was measured using a digital pH meter, as Jackson41 described. Soil organic carbon (SOC) was determined using a titration method adapted from Walkley and Black42 and soil organic matter (SOM) content was calculated by multiplying the total organic carbon content by 1.72. Soil nitrogen was determined using the micro-Kjeldahl method43, and phosphorus was analyzed using UV-spectrophotometry, following44 Potassium content was identified using a flame photometer, as per Pratt45. CHNSO analysis was carried out using instruments provided by the Sophisticated Test and Instrumentation Centre, Cochin University of Science and Technology Campus, Kochi 682 022, Kerala, India. The hydrogen-to-carbon (H/C) and oxygen-to-carbon (O/C) atomic ratios were calculated based on the obtained elemental composition data.

Metagenomic analysis

Metagenomic DNA extraction from soil samples was performed using the Nucleospin Soil Kit (MN), following the manufacturers guidelines to ensure optimal yield and purity of DNA. The quality of the extracted DNA was critically assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. The A260/280 ratio, a key indicator of DNA purity, was measured to confirm that the samples were free from significant protein or phenol contamination, which could interfere with downstream applications. This initial quality check is essential for ensuring the reliability of subsequent molecular analyses.

Following DNA extraction, the preparation of the amplicon library was carried out using the Nextera XT Index Kit from Illumina Inc. This kit is specifically designed for efficient library preparation in metagenomic studies, particularly for targeting the 16S rRNA gene, which is widely used for profiling bacterial communities46. The library preparation process was performed according to the 16S metagenomic sequencing library preparation protocol, ensuring the libraries were compatible with Illumina’s sequencing platforms.

Primers for amplifying the bacterial 16S rRNA gene region were custom-designed and synthesized by Eurofins Genomics Lab. PCR amplification was employed to amplify the 16S rRNA gene region from the extracted metagenomic DNA. A small aliquot of the PCR product, specifically 3 µL, was resolved on a 1.2% agarose gel using electrophoresis at 120 V for approximately 60 min. This step was essential for verifying the size and integrity of the amplified DNA fragments. The gel electrophoresis allowed for the visualization of the PCR products, confirming that the amplification had produced the expected amplicon size, which is indicative of successful target amplification47.

The amplified DNA libraries were subsequently subjected to quality control analysis using the 4200 TapeStation System from Agilent Technologies. The TapeStation analysis, conducted with D1000 ScreenTape, provided a detailed profile of the library sizes, with the mean peak size being a critical parameter. This information was used to determine the appropriate concentration for loading the libraries onto the sequencing platform, ensuring optimal cluster generation during sequencing.

The libraries were then loaded onto the Illumina MiSeq platform for paired-end sequencing. Paired-end sequencing is a powerful technique that allows each DNA fragment to be sequenced from both ends48, providing more comprehensive coverage and higher accuracy in identifying and classifying bacterial species. The libraries were bound to complementary adapter oligonucleotides on a paired-end flow cell during sequencing. These adapters were specially designed to enable selective cleavage of the forward strand, allowing for the reverse strands re-synthesis and subsequent sequencing.

This strategy ensures that both strands of the DNA fragments are sequenced, enhancing the accuracy and depth of the metagenomic analysis49. The resulting sequence data provided a detailed overview of the microbial communities present in the soil samples, offering insights into the diversity and composition of bacteria within the metagenome. Through this meticulous process of DNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing, the study aimed to reveal the microbial dynamics in soil, contributing valuable knowledge to metagenomics and environmental microbiology.

Plant growth and yield parameters

Plant height

The plant height was recorded from the root zone to the tip of the leaf at intervals of 15, 30, 45, and 60 days. The average height of the plants was calculated in centimetres, with measurements taken from five plants per pot50. This systematic approach ensured accurate growth tracking over the specified periods, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of plant development in response to the different treatments applied.

Yield parameters

Following the harvest, the fresh mass of plants of Amaranthus cruentus was measured for each pot and converted into total yield expressed in grams/square meter51.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis examined soil and plant factor variations across distinct seasons (Rabi and Kharif) and phases (preharvest and post-harvest). Here, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the statistically significant differences between the groups. Where ANOVA indicated significant differences (p < 0.05), Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test was applied for mean separation to identify specific group differences, ensuring consistent interpretation of multiple comparisons52.

Complementary to ANOVA, the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to analyze medians when data deviated from normality, providing robust results53. Effect sizes were quantified using eta-squared (ƞ-squared) to represent the proportion of variance attributed to the independent variable54.

All analyses were conducted using MATLAB with the Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox (MathWorks Documentation). Pearson Correlation Coefficient was employed to determine correlations among physical, chemical, and bacterial phylum contributions to the enrichment of sandy loam soils.

Results

Physicochemical parameters of soil and manure

The study has been conducted to analyze the selected soils physical parameters, essential for the growth of the selected crop, Amaranthus cruentus. Before sowing seeds into the pot, the soil and manure analysis (Table 1) was carried out, as shown in Fig. 2. During the Rabi season of preharvest, the bulk density of sandy loam soil showed 1.236 ± 0.05 g/cc in the control, whereas with manures, it ranged from 0.161 ± 0.01 to 0.07966 ± 0.003 g/cc. After the addition of manures to the soil and after the growth and yield of the crop, when the soil was analyzed, there was a reduction in the bulk density was noticed with a range of 0.15 ± 0.01 to 0.976 ± 0.11, though very little change was noticed in the case of control (1.1733 ± 0.055). Similar trends have also been observed in the Kharif season, with control posing a high bulk density compared to other manure addition soils with low bulk density values. A strong negative correlation has been noticed with Proteobacteria (r = −0.6232) and Firmicutes (r = −0.9445), indicating that compacted soils will hinder the activity of microbes due to less pore space and aeration. In both seasons, adding biochar + poultry manure has decreased the bulk density of the soil.

The characteristic sandy loam soil typically exhibits low moisture content. Soil moisture measurements during the study showed the control had the lowest moisture levels, which gradually increased with the addition of manure across both the Rabi and Kharif seasons. The combined biochar + poultry manure treatment demonstrated significantly higher soil moisture levels compared to other manure treatments (Fig. 2). One-way ANOVA revealed significant differences (p < 0.05) in soil moisture and water holding capacity (WHC) among treatments in both seasons, and post hoc analysis using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test indicated that biochar + poultry manure significantly improved moisture retention compared to the control and other manure treatments. Given that some data deviated from normality, the Kruskal–Wallis test was also applied and confirmed the significant treatment effects on moisture content and WHC. Our tests confirmed the challenging water retention in sandy soils but showed that manure applications, particularly biochar + poultry manure, enhanced WHC, with this treatment recording the highest values in both seasons Strong positive correlations existed between WHC and total organic carbon (TOC) in both seasons (r = 0.83 in Rabi and r = 0.84 in Kharif), indicating that higher organic matter content improves water retention. Additionally, WHC correlated positively with Proteobacteria abundance, suggesting soils with greater water content support the growth of nitrogen-fixing microbes. The correlation between seasons was high (r = 0.997), indicating consistent WHC across seasonal variations.

Figure 3 provides the assessment of different chemical parameters of soil in two different seasons (Kharif and Rabi) by the application of different treatments from KR1 to KR5. One of the essential characteristics of the soil is the analysis of total organic carbon (TOC). During Kharif and Rabis post-harvest seasons, the TOC range is from 0.15 to 2.88%. From all the treatments, KR5 has shown the highest levels of TOC post-harvest of Kharif with 2.88%, compared to KR2, which has the lowest levels of 0.152%. This indicates that the treatment KR5 effectively retains the soils organic carbon, enriching the organic inputs that limit carbon loss. Similarly, organic matter also plays an important role in improving soil health, indicating water retention, and increases the availability of nutrients and soil structure; the organic matter is in the range of 0.02 to 0.428%. The post-treatment of Kharif with KR3 treatment has shown 0.42%, which indicates the treatment has been providing a good source of organic matter to the soil.

The hydrogen percentage was determined to understand the decomposition of microbes in the soil and nutrient cycling. The content of hydrogen (H%) varied from 0.51% in treatment KR1 to 4.56% in KR5. The lower levels of hydrogen percent were probably identified in KR1 and KR2, which might be due to less availability of organic matter, which interferes with the bacterial decomposition rate to release the hydrogen. Similarly, the sulphur content in the soil improves soil fertility and the synthesis of plant protein; in the present study, the sulphur content is in the range of 0.04% to 0.62%. Here, the treatment of KR5 also showed a high percentage of sulphur, whereas KR1 and KR2 had less, indicating that many nutrients were unavailable.

Even though the hydrogen-carbon ratio is an important factor in the soil, a high ratio of hydrogen carbon indicates the fresh input of sources, and a lower ratio indicates more decomposed matter; the ratio ranges from 0.2% to 0.58%. Post-harvest of Rabi and Kharif has shown a high H/C ratio, with KR5 showing higher values reflecting more decomposed material in the soil profile. Similarly, the oxygen and carbon ratio has shown significant improvement in the treatment of KR5 (Fig. 3). The seasonal variations of two crops (Rabi and Kharif) notably showed improvement in soil characteristics due to the addition of the manures, whereas the KR5 treatment showed superior results.

The complete dataset included a detailed analysis of six major chemical parameters critical for soil nutrient enhancement: pH, Nitrogen (N), Potassium (K), Phosphorus (P), Carbon (C), and Oxygen (O) across five treatments in two seasons (Fig. 4). Initial measurements before sowing established baseline soil and manure characteristics, showing control soil pH, while chemical fertilizers and organic manures ranged from neutral to alkaline. Post-harvest soil analysis of Rabi and Kharif seasons revealed that KR2 and KR3 treatments exhibited higher alkalinity compared to other treatments. One-way ANOVA demonstrated significant differences (p < 0.05) in nitrogen content among treatments, further clarified by Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc test, which revealed KR5 retained higher nitrogen, notably with a 7.9% increase over control in the Kharif post-harvest. For data that did not meet ANOVA assumptions, the Kruskal–Wallis test was employed to confirm significant differences. Additionally, nitrogen levels in both seasons correlated positively with Proteobacteria abundance (r = 0.6785 in Rabi, r = 0.9123 in Kharif), emphasizing nitrogens essential role in promoting bacterial growth. Phosphorus levels in KR1 are very limited due to the sandy, loam soil nature, but after the addition of synthetic fertilizers and organic manures, the percentage of phosphorus has improved to 16.3% in KR5. The trend of potassium levels was quite different in both the Rabi and Kharif seasons. Initial application of KR2 has provided good retention in the soil after the post-harvest of Rabi, but due to the sandy, loam nature of the soil, the content of potassium was reduced in the post-Kharif season. The addition of organic manure to the soil slowly increased the percentage of potassium, which showed the highest in KR5. The carbon content was also exhibited to be higher in the organic amendments (KR3, KR4, and KR5), with KR5 showing the highest rate, which might be due to the synergetic effect of the combination of poultry manure and biochar, whereas KR1 and KR2 remained at low levels. A similar trend has been observed with the oxygen levels of KR3, KR4, and KR5 in the post-analysis of Kharif, credited to the progressed soil structure and aeration by the organic treatments. Seasonal variation has shown an improvement in chemical characteristics after the post-analysis of Rabi and Kharif, with post-Kharif indicating a higher nutrient availability might be due to the warmer climate promoting the activity of the microbes and the decomposition of organic matter. In all the treatments, KR5 has shown a significant treatment to improve the quality of the sandy loam soil compared to other treatments. The semitropical monsoon climate with distinct wet and dry seasons, high temperatures, and variable humidity may influence biochar and poultry manure efficacy. Biochar’s porous structure can enhance water retention during droughts, while combined amendments improve nutrient retention during intense rains, buffering soil quality against climatic variability.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) assessment

The FTIR analysis was conducted on the treatments of KR1 to KR5 to identify the functional groups present in these treatments to understand their chemical complexity and potential to improve sandy loam soils. The treatments have shown several peaks corresponding to functional groups significantly related to physical and chemical characteristics. The peak at 1604 cm−3 indicates the N–H stretch of amines and amides, indicating the presence of nitrogen compounds, which is a critical indicator of releasing a steady nitrogen source to the soil. The 1404 cm−3 peak indicates the presence of carboxylic acids (O–H) in the KR5 (Fig. 5) have the ability to improve the cation exchange capacity of sandy loam soil; the enhancement of CEC in soils improves the retention of nutrients such as potassium, calcium, and magnesium. The peak at 1332 cm−1 determines the presence of the nitro group (NO3), which implies nitrate assistance to the soil. One of the major macronutrients is required by plants for good growth; this peak indicates that the manure is our nitrate basin, which enhances plant growth and productivity. The functional groups of P = O (phosphine oxides), C-N (amines), and C-O (alcohol and anhydrides) at 1166 cm−1 peak show a distinct composition; these groups help in upgrading the activity of microbes and organic matter, as alcohols and amines provide an energy source for the soil microbes. The 1021 cm−1 peak has been found in all treatments, indicating the C-O alcohols and anhydrides. C–O–C stretching (ethers) and C-F stretching (alkyl halides). Influencing the formation of organic matter, which is very important to sandy loam soils that lack the natural organic content. The identified groups of these treatments provide the essential components such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon, thereby improving the soil parameters to increase the crop yield.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) assessment

The morphology and elemental composition changes observed through SEM–EDX highlight the transformative effects of different amendments on sandy, loam soils, emphasizing their mechanical and biochemical significance. KR1 demonstrates a baseline composition with limited nutrient enrichment and high levels of titanium and iron, indicative of minimal organic interaction, representing a compact structure with dense and irregular, it comprises a granular and rough texture, which indicates the limited porosity that might be able to retain water in the soil. Though KR2 shows a moderate increase in macronutrients like nitrogen and potassium, it is deficient in organic carbon enrichment, and there is a visibility of flaky structures, which show some porosity (Fig. 6). There is a potential increase of carbon content (83.94%), highlighting the potential to enhance soil organic matter, and the morphology of KR3 appeared as a honeycomb, indicating a very good source of porosity, colonization of microbes, and water retention; thus, improving water holding capacity of the soil, which in general shows high transpiration of sandy loam soils. The amendment KR4 indicates a balanced improvement in nutrients such as magnesium, calcium, organic carbon invading microbial activity, and nutrient cycling, and the surface appeared to be rough with small pores, which could be the possibility of intermediate porosity and nutrient retention. The combination of biochar and poultry manure (KR5) with a significant increase of oxygen (40.0%), carbon (47.51%), and silicon (7.91%), showing enhanced water retention, and the morphological structure describes nutrient retention and activity of microbes in the sandy loam soils.

Powder X-Ray diffraction (XRD) assessment

The XRD (Fig. 7) graph illustrates the crystalline phases in all the treatments, KR1 to KR5. The X-axis represents the diffraction angle, indicating specific crystalline compounds, while the Y-axis shows diffraction intensity proportional to phase abundance. As it is clearly noted that KR1 shows peaks at ~ 26.6º and ~ 20.9º, likely SiO2 (quartz), with smaller peaks (~ 12º, ~ 36º, and ~ 50º) indicating feldspars or silicate minerals. KR2 showed a peak at ~ 29.4º and a broad peak (~ 18º, ~ 32º) linked with ammonium nitrate or nitrogen-based compounds (Fig. 7), highlighting fertilizer crystalline structure, whereas KR3 exhibits a broader peak (~ 25º) for amorphous carbon and KR4 indicating peaks at ~ 31.7º, ~ 45º for the presence of hydroxyapatite and ~ 23º and ~ 35º for phosphate or carbonate minters, reflecting nutrient rich manures. Finally, KR 5 shows peaks close to ~ 25º indicating amorphous carbon, and ~ 31.7º & ~ 45º showing the presence of hydroxyapatite, retaining soil quality and silicates at ~ 20.9º, ~ 26.6º & ~ 50º; this analysis highlights the mineralogical impact of individual treatments and their synergistic effects on soil.

Metagenomic assessment

The metagenomic analysis has clearly stated that the KR 5 treatment has enhanced the soil bacterial community, that are very important for nitrogen availability and cycling, leading to soil fertility. The treatment KR5 has described the highest microbial diversity and abundance among all the treatments, with a proper distribution of the main phyla like Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, and Chloroflexi. These bacterial groups are essential for nitrogen fixation, nitrification, and decomposition of organic matter, which precisely enhance the soils nitrogen levels. The combination of biochar and poultry manure in KR5 has created optimum conditions for bacterial colonization due to the presence of nutrients and a stable habitat for microbes due to the porous nature of biochar. The synergistic impact increased microbial activity and enhanced the availability and retention of nutrients in the soil for a very long time. In the case of KR1, due to a lack of amendments, it showed the lowest microbial abundance, and the synthetic treatment (KR2) also indicated less bacterial diversity. Even KR3 and KR4 also showed bacterial diversity, but KR5 showed robust and diverse microbial dynamics. The presence of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes phyla shows the increased nitrogen-transforming bacteria, which boosts the nitrogen cycling process compared to other treatments. Moreover, biochar in KR5 sustains microbial activity (Fig. 8), which might improve soil structure by combining it with poultry manure. This treatment illustrates an integrated approach to soil management for sustainable agriculture.

Growth and yield parameters

Figure 9 demonstrates the effect of different soil amendments on the plant height of Amaranthus cruentus at different stages (15, 30, 45, and 60 days after sowing) during the Rabi and Kharif seasons. Plant height was measured in centimetres, where KR5 has shown improved height compared to other treatments. At its initial state (15 DAS), KR5 showed an advantage when evaluated with other amendments, possibly due to improved soil structure and nutrient availability. As the growth progressed towards 30 DAS, the stage clearly gave a distinction between organic and synthetic inputs, but the performance of KR5 might be due to the synergistic effects of biochar to retain moisture and nutrients, and poultry manure providing a steady supply of organic nitrogen and other required elements. Growth improvement was observed at 45 DAS and harvest (60 DAS), the plant height reaching 40 cm in the Kharif season, highlighting the organic supplement of KR5 (Fig. 10). Other treatments, such as KR4, KR3, and KR2, also showed improvement, but less than KR5. The study also showed the yield of the Amaranthus cruentus crop, which significantly showed a higher rate in the KR5 treatment in both Rabi and Kharif seasons (Fig. 11), with its performance in the Kharif season superior to that in Rabi, likely due to more favourable climatic conditions, such as high moisture availability and temperature during the Kharif season. The yield of KR5 exceeds 550 g per square meter, making it the most efficient treatment. KR4 and KR3 also determined substantially better yields than KR1 and KR2, emphasizing the benefits of organic treatments enhancing soil fertility and microbial activity, which directly influences plant growth and productivity.

Discussion

Physicochemical characteristics of soil

The current research explores the combination of biochar from Syzigium cumin sawdust and poultry manure, which can improve the physical properties of sandy loam soil, a challenging medium for agriculture due to its weak retention of water and high bulk density. The treatments were assessed to evaluate their effects on soil quality, reduce pollutants55), and the growth of Amaranthus cruentus. Due to the coarse texture of sandy loam soil, with large particles that easily drain water quickly and hold fewer nutrients. High bulk density often signifies compacted soil, which inhibits root growth and less water infiltration, but after the addition of organic amendments, a reduction was observed. This could be due to the porous nature of biochar, which might create air pockets in the soil, and organic matter in the poultry manure improves soil aggregation56. After the crop harvest, the bulk density was lower in the amended soils compared to KR1. The reduction in bulk density observed in our study aligns with previous research, which reported that organic amendments improve soil porosity and reduce compaction, making it feasible for microbial activity57,58. The strong negative correlation with Firmicutes and Proteobacteria mirrors earlier research59, exhibiting that those packed soils limit the diversity of microbes due to low aeration. An additional crucial improvement identified is the retention of water,in general, sandy loam soil struggles to hold water due to its large pore size, which leads to fast drying; however, the KR2 and addition of organic amendments has enhanced soil moisture in both the Rabi and Kharif seasons, particularly with the combination of biochar and poultry manure. Our study, associated with60, emphasizes that biochar efficacy in retaining moisture enhances water retention in sandy loam soils. The microporous biochar structure acts like a sponge, holding water, and poultry manure retains organic matter, which retains moisture. This water retention helps provide sufficient moisture content for crop growth, reducing the stress of irregular watering as studied by Osman et al.61. Better soil promotes healthier root development, efficient nutrient uptake, and increased crop productivity.

One of the characteristics that maintains soil health is total organic carbon, which impacts the ability of the soil to retain moisture and nutrients. In general, soil organic carbon ranges from 0.15% to 3.0%62,in the current study, the levels of TOC ranged from 0.15% to 2.88%, which were found after the post-harvest of the Kharif season of KR5 treatment. This improvement might be due to the combined effect of biochar and poultry manure, which improves organic carbon in the soil while reducing the carbon losses through microbial respiration. Biochar exhibits high carbon content, and poultry manure helps in the degradation of organic material, which leads to the maintenance of TOC in sandy loam soils63. It was clearly identified that the presence of TOC is higher in KR3, which supports the idea that biochar application tends to improve the carbon content in the soils due to microbial activity64. The application of KR3 and KR5 has improved the TOC in the soil, which was previously demonstrated by the findings of65, leading to improved soil health and sustainability. The strong positive correlation between WHC, TOC, and microbial activity supports earlier insights66that organic carbon is crucial for the proliferation of microbes and the fixation of nitrogen. Even major studies revealed that the addition of organic treatments not only enriches the soil but also improves plant growth67,68,the same has been noticed in our work with the improved plant growth and yield of the Amaranthus cruentus crop.

The dynamics of hydrogen and sulphur play an important role in soil enrichment and plant growth. As hydrogen serves as an indicator of the activity of microorganisms and the decomposition of organic matter. The lower hydrogen levels might indicate less microbial colonization with low hydrogen release, whereas the high hydrogen levels in KR5 clearly indicate the decomposition of organic matter by microbes that has been related to the study of Wu et al.69,, emphasizing the potential of hydrogen in the rate of decomposition that clearly identified in our study which was facilitated by biochar and poultry manure. Even sulphur has shown a similar trend, exhibiting low in KR1 and KR2 and high in KR5, likely due to the action of sulphur reduction bacteria, which even increases the hydrogen levels, thereby increasing the pH registered,a similar study has been carried out by70. Hydrogen-to-carbon and Oxygen-to-carbon ratios also play a valuable role in considering the degree of organic decomposition. A higher hydrogen to carbon (H/C) ratio might indicate the fresh organic introduction or retention in a longer time, as in KR5, while a lower ratio indicates more decomposed material found in KR1, as reported by69. Similarly, the oxygen-to-carbon ratio also showed a similar trend in the KR5-treated soils.

The study also focused on the availability of macronutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, which play an important role in the growth and development of plants. The percentage of nitrogen has shown a significant increase in the post-harvest of Kharif in KR5, with 25% higher than that of the initial analysis. This might be due to the slow release of nitrogen from the organic treatments from KR5, which reduces the leaching of nitrogen, as it is believed to be a general issue with the texture of the sandy loam soils. Similar studies were carried out by71. The positive correlation with the Proteobacteria (r = 0.6785 in Rabi and r = 0.9123 in Kharif) could be the presence of nitrogen-fixing bacteria, which might enhance the nitrogen levels in the soil, where the findings have been related to72,73,74. According to75,76, the tendency of the biochar to adsorb and release nutrients steadily was also found in our study when it was mixed with poultry manure. Initially, the level of phosphorus was limited due to the nature of sandy loam soils, but it improved and recorded the highest in KR5 with 16.3% post-Kharif season, probably due to improved phosphorus binding capacity with the biochar and the nutrient-rich characteristic of poultry manure77,78. There was a variation in the trend of potassium levels noticed in both the Rabi and Kharif seasons. In all treatments, KR2 has shown high retention of potassium levels but was found to be gradually reduced at post-Kharif season,this might be due to the leaching propensity of sandy soils79. However, a significant increase was noticed in KR5 treatment, showing the highest levels among all treatments of the post-Kharif season,this enhancement can be credited to the synergistic effects of poultry manure and biochar combination, which reduced the potassium leaching and improved its retention in the soil matrix. A set of environmental factors also determines the availability of nutrients in the soil, and the growth of microbes, and their activity also depends on climatic characteristics. The temperature fluctuations influenced the activity of microbes in the soil80,81,82, which helped in nutrient retention,the warmer temperatures promoted good growth of microbes in the soil, making the decomposition of organic matter faster, leading to the availability of nutrients and better crop yield. But in Rabi, slower microbial activity has been displayed, which reflected the influence of the temperature on the biological process of soil, resulting in less nutrient retention. KR5 has consistently shown better results compared to other treatments in these two seasons.

pH plays a vital role in the availability of nutrients at various treatments, before treating the soil with the treatments, the pH has shown basic to slightly alkaline, but after harvest in the case of KR2 and KR3, there has been inclined towards alkalinity; however, KR5 has maintained a balanced pH which might show an optimal condition for microbial activity and nutrient retention.

The long-term application of biochar and poultry manure typically results in sustained or progressively improved soil fertility over several seasons. Biochar’s stable carbon structure enhances soil organic carbon, water retention, and microbial habitat, which cumulatively improve soil physical and chemical characteristics. Poultry manure contributes essential nutrients and organic matter that slowly mineralize, maintaining nutrient availability. Studies show that combined use reduces bulk density, increases porosity and nutrient levels, and supports ongoing crop productivity. While benefits may plateau, these amendments generally prevent fertility decline and promote sustainable soil health in the long term83,84

FTIR, SEM–EDX &XRD assessment

The FTIR (Fig. 5) analysis of different treatments of the present study (KR1 to KR5) projects an advanced chemical profile showing their capacity to improve the physicochemical properties of sandy loam soils, which are often considered to have low organic content and less nutrient retention. N–H stretching of amines and amides clearly indicates the nitrogen, which has a direct impact on chlorophyll synthesis, metabolic pathways, and protein formation; the treatments help in minimal loss through leaching85,86, which is further complimented by the 1332 cm−1 peak, which highlights the bioavailable of nitrogen87. The presence of carboxylic acid (O–H) might enhance the soil cation exchange capacity, which makes retaining cations such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium play an important role in the plant cells osmotic regulation and enzymatic activity88. The presence of phosphine oxides (P = O) indicates that one of the macronutrients, phosphorus, is available for energy transfer and root development. This group could also facilitate the bioavailability of the phosphorus pool, assisting microbial activity and crop productivity89. The presence of C–O–C in the treatment indicates an increase in organic matter. Organic matter is essential for sandy loam soils, which enhances water holding capacity, aeration, and aggregation, further improves energy substrates for soil microbes driving nutrient mineralization, and enhances the soil ecosystem90,91, increasing soil structure and nutrient dynamics. Similarly, the surface morphology and porosity (Fig. 6) of the treatments KR1 to KR5 determine their efficacy in the retention of nutrients and colonization of microbes in sandy loam soils92,93,94. Even the elemental composition of the KR5 sample has shown better results when analysed through EDX (Fig. 6) and could be in a position to boost the soil. Although it has been studied previously that manures are always a provider to improve soil health, our study correlates with95, indicating that these elements, when combined with the deficient concentration of existing elements, improve the quality and enhance crop growth. Secondly, the presence of these phyla, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, and Chloroflexi, also improves soil health and quality, favouring plant growth, as our findings were associated with96,97. In our study, the porosity of the honey web structure in KR3 offers microbial colonization due to porous surface area, which improves microbial activity and nutrient mineralization, and KR5, which exhibits a flake-like structure that increases soil aggregation, clearly showing the growth and yield parameters of the Amaranthus cruentus crop. The XRD (Fig. 7) data clearly stated the presence of the crystalline structure of KR1 and the amorphous nature of other treatments like KR3. The synergistic impact of KR5 is also clearly noted, which is essential for managing these soils. Further enhancement of nutrients and the synergistic impact on soil using the developed materials shows comparable and higher benefits with existing developments, which are summarized in Table 2.

Metagenomic assessment

Microbial communities have an interesting role in nutrient cycling, particularly in nitrogen dynamics103,104. The treated KR5 (biochar + poultry manure) created a conducive environment for the soil microbial colonization and activity. Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, and Chloroflexi have improved nitrogen availability and soil fertility, supporting plant growth105. In particular, Proteobacteria contain nitrogen-fixing genera such as Rhizobiales, which convert atmospheric nitrogen (N2) to plant-available ammonia (NH3) via the nitrogenase enzyme, while other members participate in key nitrogen cycling pathways, including assimilatory and dissimilatory nitrate reduction, nitrification, and denitrification, using genes like nasA, nirA, narG, nirK, nosZ106. Firmicutes contribute primarily to organic matter decomposition and are involved in denitrification, aiding nutrient turnover107,108. Actinobacteria play a role in mineralization and decomposition of organic materials, while Chloroflexi assist in recycling organic carbon and nitrogen, enhancing nutrient retention and cycling109,110.

Similar phyla have been observed in the present study, where Proteobacteria and Firmicutes with higher percentages might contribute to nitrogen cycling pathways such as ammonification, nitrification, and denitrification. The percentage of these phyla has varied from KR1 to KR5, where the presence of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes indicates the nitrogen cycling process. The presence of nitrogen-fixing bacteria such as Rhizobiales within Proteobacteria and nitrifying bacteria like Nitrosomonadaceae improves the nitrogen facility in the soil107,111, converting atmospheric nitrogen to available nitrogen for plant growth. The amendments KR5 (biochar + poultry manure) promote these mechanisms by supplying both a porous microhabitat and organic substrates, which facilitate microbial colonization, provide energy sources, and create a stable habitat for enzymatic activity. Biochar enhances air and water retention and adsorbs nutrients to reduce leaching while poultry manure supplies organic nitrogen and carbon112,113. Together, these amendments increase the abundance and activity of nitrogen-transforming microbes and their corresponding functional genes, which drive the nitrogen cycle and improve sustainable crop growth. Therefore, the amendment KR5 has improved the soil microbial ecology, which has enhanced the nutrient availability in the sandy, loam soils, thereby improving plant growth and yield.

Research shows biochar can promote nitrifying and nitrogen-fixing bacteria, enhancing nitrogen retention and availability. Investigating biochar interactions with specific nitrogen-fixing taxa could reveal targeted strategies to optimize soil fertility and sustainable nutrient management81,82.

Growth and yield parameters

The highest yield observed in the KR5 treatment across both seasons highlights the positive effect of combining biochar and poultry manure on soil fertility and crop productivity. This combination appears to support both immediate nutrient availability and improvements in soil health indicators, suggesting potential benefits for soil quality over time[114][97]. Biochar enhances the soil structure by improving porosity, cation exchange capacity, water retention, and reducing nutrient leaching115,116, whereas poultry manure supplies require macronutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium,in our study, the combination of both biochar and poultry manure has shown a significant increase in plant height and yield. Furthermore, the presence of biochar facilitates the proliferation of microbes by providing a habitat for soil bacteria, whereas poultry manure acts as a substrate, driving microbial activity117, the SEM analysis of our study in the KR5 has clearly indicated the presence of porosity which determines the active colonization of bacteria for the better growth and yield of the Amaranthus cruentus crop. The study was further justified with the metagenomic analysis, where the diverse, abundant microbial communities, like Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Chloroflexi, played an instrumental role in nitrogen fixation, nitrification, and organic matter decomposition, where nitrogen plays a key role in plant growth and yield. Even the Pearson correlation coefficient has also shown a significant positive correlation between nitrogen and Proteobacteria and Firmicutes (r = 0.9123), which clearly indicates that the presence of bacteria traps the atmospheric nitrogen to retain and promote bacterial diversity (Fig. 12).

Biochar produced from poultry manure or woody materials has also demonstrated significant enhancements in soil physical properties, water holding capacity, and nutrient retention in sandy and sandy loam soils. Studies show poultry manure-derived biochar can increase organic carbon 1.75 times more than raw poultry manure and improve physical and chemical properties of the soil118. Although feedstock-specific differences can affect biochar performance99,119, the improvements seen with Syzygium cumini biochar are consistent with those reported for other biochar types in sandy soils120. Enhancements in microbial activity, nutrient cycling, and moisture retention align closely with known benefits from biochar combined with poultry manure, whether derived from poultry manure biochar, wood, or agricultural residues. Thus, while Syzygium cumini biochar shows strong positive effects, these are not unique but reflect the general efficacy of biochar manure mixtures in improving sandy loam soils and supporting plant growth.

While poultry manure and biochar improve soil fertility and crop productivity, limitations include potential nutrient imbalances, variable nutrient release rates, and risk of excess application leading to soil pH changes or nutrient leaching. Biochar production costs and variability in feedstock quality may hinder consistent results. Poultry manure can introduce pathogens or heavy metals if not properly processed. Also, biochar’s benefits may plateau over time, necessitating monitoring and integration with complementary soil practices for sustained fertility and environmental safety34.

Conclusions and future recommendations

The study revealed the transformative impact of organic treatments, particularly the combination of biochar and poultry manure (KR5), on increasing sandy loam soils physical, chemical, and biological properties. The application of manures has significantly reduced soil bulk density and improved water holding capacity, with KR5 showcasing the most among the other treatments in Rabi and Kharif, respectively. This could be due to enhanced porosity and soil structure provided by the biochar, which maintained moisture content and supported microbial activity. Even in the case of chemical parameters, KR5 has shown consistently increased levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, carbon, and micronutrients such as sulphur and hydrogen, which ensured the gradual decomposition of organic matter. The oxygen-carbon and hydrogen-carbon ratios in KR5 suggest that proper decomposition and nutrient cycling have occurred, which might improve soil fertility. The functional group, through FTIR in KR5, showed the presence of nitrogen compounds and carboxylic acids, which help retain nutrients and colonize microbes. The bacterial phyla, such as Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, can improve the nitrogen fixation and decomposition of organic matter, which was found to be higher in KR5. Even plant height and yield have shown higher in KR5. It has been clearly understood that the KR5 amendment has emerged as an efficient treatment in improving soil quality and yield of the Amaranths cruentus crop. Biochar and poultry manure often cost less than synthetic fertilizers, especially in large-scale farming. Poultry manure is a low-cost, locally available organic fertilizer, while biochar, though initially more expensive due to production, can be cost-effective long term by enhancing nutrient use efficiency and soil health.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (Dr. M.K. Reddy) on a reasonable request.

References

Bass, A. M., Bird, M. I., Kay, G. & Muirhead, B. Soil properties, greenhouse gas emissions and crop yield under compost, biochar and co-composted biochar in two tropical agronomic systems. Sci. Total Environ. 550, 459–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.01.143 (2016).

Diop, M., Chirinda, N., Beniaich, A., El Gharous, M. & El Mejahed, K. Soil and water conservation in Africa: State of play and potential role in tackling soil degradation and building soil health in agricultural lands. Sustainability 14(20), 13425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013425 (2022).

Farid, I. M. et al. Co-composted biochar derived from rice straw and sugarcane bagasse improved soil properties, carbon balance, and zucchini growth in a sandy soil: A trial for enhancing the health of low fertile arid soils. Chemosphere 292, 133389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.133389 (2022).

Sinha, A. K. et al. Agricultural waste management policies and programme for environment and nutritional security. Input Use Effic. Food Environ. Sec. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5199-1_21 (2021).

Naorem, A. et al. Soil constraints in an arid environment—challenges, prospects, and implications. Agronomy 13(1), 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13010220 (2023).

Unkovich, M. et al. Challenges and opportunities for grain farming on sandy soils of semi-arid south and south-eastern Australia. Soil Res. 58(4), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR19161 (2020).

Gavrilescu, M. Water, soil, and plants interactions in a threatened environment. Water 13(19), 2746. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13192746 (2021).

Siebielec, S. et al. Impact of water stress on microbial community and activity in sandy and loamy soils. Agronomy 10(9), 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10091429 (2020).

Chaudhari, S., Upadhyay, A. & Kulshreshtha, S. Influence of organic amendments on soil properties, microflora and plant growth. Sustain. Agric. Rev. 52, 147–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73245-5_5 (2021).

Dai, Z. et al. Association of biochar properties with changes in soil bacterial, fungal and fauna communities and nutrient cycling processes. Biochar 3, 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-021-00099-x (2021).

He, Z. et al. The impact of organic fertilizer replacement on greenhouse gas emissions and its influencing factors. Sci. TotalEnviron. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166917 (2023).

Mian, M. M., Alam, N., Ahommed, M. S., He, Z. & Ni, Y. Emerging applications of sludge biochar-based catalysts forenvironmentalremediation and energy storage: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 360, 132131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132131(2022).

Mulinari, J. et al. Biochar as a Tool for the Remediation of Agricultural Soils. Biochar Appl. Bioremed. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-4059-9_13 (2021).

Rondon, M. A., Lehmann, J., Ramírez, J., & Hurtado, M. Biological nitrogen fixation by common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) increases with bio-char additions. Biol. Ferti. soils, 43(6), 699-708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-006-0152-z (2007).

Ingold, M. et al. Effects of activated charcoal and quebracho tannin amendments on soil properties in irrigated organic vegetable production under arid subtropical conditions. Biol. Ferti. soils, 51(3), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-014-0982-z (2015).

Kumari, S. et al. Effect of supplementing biochar obtained from different wastes on biochemical and yield response of French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): An experimental study. Biocatal. Agri Biotechnol, 43, 102432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2022.102432 (2022).

Major, J. et al. Maize yield and nutrition during 4 years after biochar application to a Colombian savanna oxisol. Plant Soil, 333, 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-010-0327-0 (2010).

Jalal, F. et al. Biochar as sustainable input for nodulation, yield and quality of mung bean. J.Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appll. Sci., 10, 510–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43994-024-00121-5 (2024).

Steiner, C. et al. Biochar as bulking agent for poultry litter composting. Carbon Management, 2(3), 227–230. https://doi.org/10.4155/cmt.11.15 (2011).

Oladele, S. et al. Effects of biochar amendment and nitrogen fertilization on soil microbial biomass pools in an Alfisol under rainfed rice cultivation. Biochar, 1, 163–176 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-019-00017-2.

Rasool, A. et al. Effects of poultry manure on the growth, physiology, yield, and yield-related traits of maize varieties. ACS Omega 8(29), 25766–25779. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c00880 (2023).

Vaccari, F. P. et al. Biochar as a strategy to sequester carbon and increase yield in durum wheat. Eur.J.Agron., 34(4), 231-238.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2011.01.006 (2011).

Latini, A. et al. The impact of soil-applied biochars from different vegetal feedstocks on durum wheat plant performance and rhizospheric bacterial microbiota in low metal-contaminated soil. Front. Microbiol, 10, 2694. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02694 (2019).

Leogrande, R. et al. Residual effect of compost and biochar amendment on soil chemical, biological, and physical properties and durum wheat response. Agronomy, 14(4), 749. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14040749 (2024).

Ding, Y. et al. Enhancing soil health and nutrient cycling through soil amendments: Improving the synergy of bacteria and fungi. Sci. Total Environ. 923, 171332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171332 (2024).

Fageria, N. K. Role of soil organic matter in maintaining sustainability of cropping systems. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 43(16), 2063–2113. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103624.2012.697234 (2012).

Adekiya, A. O. et al. Different organic manure sources and NPK fertilizer on soil chemical properties, growth, yield and quality of okra. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73291-x (2020).

Ayito, E. O. et al. Synergistic effects of biochar and poultry manure on soil and cucumber (Cucumis sativus) performance: A case study from the southeastern Nigeria. Soil Sci Ann., 74(4). https://doi.org/10.37501/soilsa/183903 (2023).

Adegoke, K. A. et al. Sawdust-biomass based materials for sequestration of organic and inorganic pollutants and potential for engineering applications. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 5, 100274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crgsc.2022.100274 (2022).

Adesina, I. et al. An overview of biochar application on biological soil health indicators and greenhouse gas emission. Soil. Managt. Sustain. Agri. 143-169. (2022).

Ali, L. et al. Characteristics of biochars derived from the pyrolysis and Co-pyrolysis of rubberwood sawdust and sewage sludge for further applications. Sustainability 14(7), 3829. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073829 (2022).

Grojzdek, M., Novosel, B., Klinar, D., Golob, J. & Žgajnar Gotvajn, A. Pyrolysis of different wood species: influence of process conditions on biochar properties and gas-phase composition. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 14(5), 6027–6037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-021-01480-3 (2024).

Naga J, Kiranmai R. Optimizing Spinacia oleracea L. yield in semi-arid region: The role of hydrogel in water scarcity mitigation.Plant Sci. Today, 12(3)., 1-11. http://doi.org/10.14719/pst.9337 (2025).

Agbede, T. M. et al. Impacts of poultry manure and biochar amendments on the nutrients in sweet potato leaves and the minerals in the storage roots. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 16598. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67486-9 (2024).

Rassem, A. M. & Elzobair, K. A. The effects of biochar and chicken manure on the growth and yield of pea in sandy soil. Bani Waleed Univ. J. Humanit. Appl. Sci. 9(5), 360–367. https://doi.org/10.8916/jhas.v9i5.566 (2024).

Liu, L. et al. Combined effects of biochar and chicken manure on maize (Zea mays L.) growth, lead uptake and soil enzyme activities under lead stress. PeerJ 9, e11754. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11754 (2021).

Somboon, S. et al. Mitigating methane emissions and global warming potential while increasing rice yield using biochar derived from leftover rice straw in a tropical paddy soil. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 8706. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59352-5 (2024).

Qi, J. Q. et al. Effect of different types of biochar on soil properties and functional microbial communities in rhizosphere and bulk soils and their relationship with CH4 and N2O emissions. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1292959. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1292959 (2023).

Jeffery, S., Verheijen, F. G., Kammann, C. & Abalos, D. Biochar effects on methane emissions from soils: a meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 101, 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.07.021 (2016).

Misra, R. Ecology Work Book Oxford and IBH Publishing Company. New Delhi. (1968).

Jackson, M. L. Soil Chemical Analysis 498 (Prentice-Hall Inc., 1958).

Walkley, A. J. & Black, I. A. Estimation of soil organic carbon by the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 37, 29–38 (1934).

Peach, K and Tracy, M. V., “Modern Methods of Plant Analysis, Vol III and IV,” Springer Heidelberg, Berlin, pp. 258–261. (1955).

Olsen, S.R. Estimation of available phosphorus in soils by extraction with sodium bicarbonate (No. 939). US Department of Agriculture. (1954).

Pratt, P.F. Potassium. Methods of soil analysis: Part 2 chemical and microbiological properties. 9, 1022–30. (1965).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41(D1), D590–D596. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1219 (2012).

FastQC: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30(15), 2114–2120. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 (2014).

Estaki, M. et al. QIIME 2 enables comprehensive end-to-end analysis of diverse microbiome data and comparative studies with publicly available data. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 70(1), e100. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpbi.100 (2020).

Ono, K., Miyata, A. & Mano, M. Mase flux measurement site. Agric. Meteorol. Kanto 39, 10–12 (2013).

Ulianych, O. et al. Growth and yield of spinach depending on absorbents’ action. Agron. Res 18(2), 619–627. https://doi.org/10.15159/AR.20.012 (2020).

Zar, J. H. Biostatistical analysis (Pearson Education India, 1999).

McDonald, J. H. Handbook of biological statistics (Sparky House Publishing, 2014).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Routledge Academic, 1988).

Sahu, U. K., Ji, W., Liang, Y., Ma, H. & Pu, S. Mechanism enhanced active biochar support magnetic nano zero-valent iron for efficient removal of Cr(VI) from simulated polluted water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10(2), 107077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2021.107077 (2022).

Are, K. S., Adelana, A. O., Fademi, I. O. & Aina, O. A. Improving physical properties of degraded soil: Potential of poultry manure and biochar. Agric. Nat. Resour. 51(6), 454–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anres.2018.03.009 (2017).

Agbeshie, A. A. et al. Mineral nitrogen dynamics in compacted soil under organic amendment. Sci. Afr. 9, e00488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00488 (2020).

Arshad, M. & Mansoor, M. Unveiling the Transformative Impact of Organic Amendments on Soil Physical Properties. Indus J. Agric. Biol. 2(2), 16–22. https://doi.org/10.59075/ijab (2023).

Hou, X. et al. Changes in soil physico-chemical properties following vegetation restoration mediate bacterial community composition and diversity in Changting, China. Ecol. Eng. 138, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2019.07.031 (2019).

Ibrahimi, K. & Alghamdi, A. G. Available water capacity of sandy soils as affected by biochar application: A meta-analysis. CATENA 214, 106281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106281 (2022).

Osman, A. I. et al. Biochar for agronomy, animal farming, anaerobic digestion, composting, water treatment, soil remediation, construction, energy storage, and carbon sequestration: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 20(4), 2385–2485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-022-01424-x (2022).

Labaz, B., Hartemink, A. E., Zhang, Y., Stevenson, A. & Kabała, C. Organic carbon in Mollisols of the world− A review. Geoderma 447, 116937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2024.116937 (2024).

Song, C. et al. Insight into the pathways of biochar/smectite-induced humification during chicken manure composting. Sci. Total Environ. 905, 167298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167298 (2023).

Li, B. et al. Global integrative meta-analysis of the responses in soil organic carbon stock to biochar amendment. J. Environ. Manage. 351, 119745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119745 (2024).

Morash, J. et al. Using organic amendments in disturbed soil to enhance soil organic matter, nutrient content and turfgrass establishment. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174033 (2024).

Shabir, R., Li, Y., Zhang, L. & Chen, C. Biochar surface properties and chemical composition determine the rhizobial survival rate. J. Environ. Manage. 326, 116594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116594 (2023).

Sarangi, S. S., Sarma, I., Gogoi, S. & Barooah, A. Effect of organic nutrients and bio fertilizers on soil parameters and nutritional content of amaranth. Int. J. Environ. Climate Ch. 13(11), 4326–4330. https://doi.org/10.9734/ijecc/2023/v13i113613 (2023).

Su, J. Y., Liu, C. H., Tampus, K., Lin, Y. C. & Huang, C. H. Organic amendment types influence soil properties, the soil bacterial microbiome, and tomato growth. Agronomy 12(5), 1236. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12051236 (2022).

Wu, X. et al. Microbial interactions with dissolved organic matter drive carbon dynamics and community succession. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1234. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01234 (2018).

Jayalath, N., Mosley, L. M., Fitzpatrick, R. W. & Marschner, P. Addition of organic matter influences pH changes in reduced and oxidised acid sulfate soils. Geoderma 262, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2015.08.012 (2016).

Hadroug, S. et al. Pyrolysis process as a sustainable management option of poultry manure: characterization of the derived biochars and assessment of their nutrient release capacities. Water 11(11), 2271. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11112271 (2019).

Dai, H., Chen, Y., Yang, X., Cui, J. & Sui, P. The effect of different organic materials amendment on soil bacteria communities in barren sandy loam soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 24019–24028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-0031-1 (2017).

Liu, L. et al. Combined Application of Organic and Inorganic Nitrogen Fertilizers Affects Soil Prokaryotic Communities Compositions. Agronomy 10(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy1001013210.3390/agronomy10010132 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. Comparable effects of manure and its biochar on reducing soil Cr bioavailability and narrowing the rhizosphere extent of enzyme activities. Environ. Int. 134, 105277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.105277 (2020).

Gwenzi, W., Nyambishi, T. J., Chaukura, N. & Mapope, N. Synthesis and nutrient release patterns of a biochar-based N-P–K slow-release fertilizer. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 15, 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-017-1399-7 (2018).

Marcińczyk, M. & Oleszczuk, P. Biochar and engineered biochar as slow-and controlled-release fertilizers. J. Clean. Prod. 339, 130685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130685 (2022).

Luostarinen, S., Tampio, E., Laakso, J., Sarvi, M., Ylivainio, K., Riiko, K., Kuka, K., Bloem, E. and Sindhöj, E. Manure processing as a pathway to enhanced nutrient recycling: Report of SuMaNu platform. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-380-037-3 (2020).

Lustosa Filho, J. F., Barbosa, C. F., da Silva Carneiro, J. S. & Melo, L. C. A. Diffusion and phosphorus solubility of biochar-based fertilizer: Visualization, chemical assessment and availability to plants. Soil Tillage Res. 194, 104298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.104298 (2019).

Wulff, F., Schulz, V., Jungk, A. & Claassen, N. Potassium fertilization on sandy soils in relation to soil test, crop yield and K-leaching. Zeitschrift für Pflanzenernährung und Bodenkunde 161(5), 591–599. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.1998.3581610514 (1998).

Curiel Yuste, J. et al. Microbial soil respiration and its dependency on carbon inputs, soil temperature and moisture. Glob. Change Biol. 13(9), 2018–2035. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01415.x (2007).

Zhang, H. et al. Biochar can improve absorption of nitrogen in chicken manure by black soldier fly. Life 13(4), 938. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13040938 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Temperature fluctuation promotes the thermal adaptation of soil microbial respiration. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7(2), 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01944-3 (2023).

Agbede, T. M. & Oyewumi, A. Effects of biochar and poultry manure amendments on soil physical and chemical properties, growth and sweet potato yield in degraded Alfisols of humid tropics. Nat. Life Sci. Commun 22(2), e20230. https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2023.023 (2023).

Udokpoh, U. & Nnaji, C. Reuse of Sawdust in developing countries in the light of sustainable development goals. Recent Progress Mater. 5(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.21926/rpm.2301006 (2023).

Bamdad, H., Papari, S., Lazarovits, G. & Berruti, F. Soil amendments for sustainable agriculture: Microbial organic fertilizers. Soil Use Manag. 38(1), 94–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/sum.12762 (2022).

Sharma, A., Kumar, S. & Singh, R. Synthesis and characterization of a novel slow-release nanourea/chitosan nanocomposite and its effect on Vigna radiata L. Environ. Sci. Nano 9(11), 4177–4189. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2EN00297C (2022).

Luo, G. et al. Organic amendments increase crop yields by improving microbe-mediated soil functioning of agroecosystems: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 124, 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.06.002 (2018).

Adeleke, R., Nwangburuka, C. & Oboirien, B. Origins, roles and fate of organic acids in soils: A review. S. Afr. J. Bot. 108, 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2016.09.002 (2017).

Dao, T. H. Extracellular enzymes in sensing environmental nutrients and ecosystem changes: ligand mediation in organic phosphorus cycling. Soil Enzymol. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-14225-3_5 (2011).