Abstract

E. coli mastitis is a major production disease in dairy cattle and requires alternative treatments to antibiotics. In this context, phages are of growing interest, but their host specificity remains a challenge in therapy. This study aimed to characterize eight newly isolated phages for the control of E. coli mastitis, to assess their efficacy in milk and to investigate their specificity. Physicochemical characterization of the phages was performed, followed by in vitro stability and lytic activity assays in raw and heat-treated milks. Genome sequencing of phages and bacteria was performed to investigate phage attachment. Phage stability was maintained across physiological pH and temperature ranges, as well as in raw milk. Phage lytic activity demonstrated bacterial decreases below detection level, but regrowth occurred in raw milk after 5 h of incubation with 3/8 phages. A narrow host range was linked to the diversity of the bacterial collection and to the presence of two receptor-binding proteins among Tevenvirinae. Indeed, structural analysis of the proteins revealed a variable region in the long tail fiber and a conserved short tail fiber. In conclusion, phage specificity was mainly associated with the long tail fiber and milk components didn’t hinder the efficacy of phages to control bovine mastitis, although resistance should be investigated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mastitis is an inflammatory response of the udder tissue mainly due to bacterial infection and is responsible for the most prevalent production disease in dairy cattle1. Escherichia coli (E. coli) is present in environmental reservoirs2 and is considered as a major bacterial species responsible for mastitis3. The clinical signs manifest themselves acutely and are characterized by inflammation of the affected quarter2 and general clinical signs in case of systemic dissemination4. In addition to the decrease in milk production, the milk quality of the affected quarter can be altered5. The management of E. coli mastitis mainly involves supportive treatment (fluid therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, frequent milking) and antimicrobials6, which contribute to the development and spread of antibiotic resistance.

A report from the World Health Organization (WHO) indicated the urgent need for new antibiotics targeting, among others, Enterobacteriaceae7. Since the development of new antibiotics is costly and underwhelming8, the use of bacteriophages (phages) is of growing interest in this context. These viruses are able to infect and kill their bacterial hosts and are the most prevalent microbiological entity worldwide9. Phages are composed of single or double-stranded DNA or RNA and play a role in maintaining the balance of bacterial populations and driving their evolution10. Several advantages of phages include their specificity for prokaryotic cells, aptitude to replicate at the site of infection, and ability to co-evolve with their host11. Nevertheless, this co-evolution can also lead to bacterial resistance12 and host specificity can challenge the selection of appropriate phages.

The use of viruses as a treatment entails a detailed characterization to select candidates that could safely overcome bacterial infection. Intramammary phage treatments involve a direct contact of the phages with milk components but also with the mammary epithelium and the immune system. Milk is a complex medium, and several components may interact with phages. For instance, immunoglobulins can inhibit the adhesion of microorganisms, agglutinate bacteria between each other and neutralize viruses13. Lactoferrin and lactoperoxidase also demonstrated antimicrobial and antiviral activities14,15.

The high specificity of phages enables them to target the specific strain responsible for the infection. However, lack of understanding of the phage-bacteria interactions and variability in the underlying mechanisms make it difficult to predict the appropriate phage, especially when their host range is narrow. This specificity is determined by phage adsorption, which initiates the replication cycle of phages. Adsorption involves the host recognition by receptor-binding proteins (RBPs), which are often located at the tip of the tail region16. The diversity of bacterial receptors and RBPs explain why there are almost limitless possibilities of interactions. Considering E. coli, the first obstacle faced by most tailed phages for their adsorption is the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O-antigen17. Since this antigen is highly variable, phages using this receptor have a narrow host range, which is serogroup specific. Moreover, this antigen can be masked by exopolysaccharides, which require specific enzymes for their degradation18. Other parts of the LPS or outer membrane proteins can also serve as receptors. After a first reversible attachment, secondary receptors are involved, depending on the phage morphology: siphoviruses attach mostly to porin outer membrane proteins, podoviruses on LPS core and myoviruses can use both19. The size of phage genomes also involves different immune responses of bacteria19.

The aims of this study were to assess the suitability of newly isolated and characterized phages for intramammary use against E. coli responsible for bovine mastitis and to identify and analyze phage RPBs to obtain insights into phage interactions with their hosts.

Results

Bacterial collection, antibiotic susceptibility profiles and genomic analysis

All 53 strains from the bacterial collection were grown on Coliform Extra Selective (ES) agar (Merck Millipore, USA) and were indole positive. Antimicrobial susceptibility tests demonstrated various phenotypes and 6/53 strains showed an extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) profile (Table 1). Among the 35 serogroups identified, serotype O8:H25 was predominant, accounting for 9/53 strains. No O-antigen was detected for strains 831 and 846, nor was H-antigen detected for strain 812. Few strains were related to several O-antigens (strains 2 and 855: O101 or O9; strain 834: O13, O129 or O135; strain 844: O17, O73 or O77). Twenty-four different sequence types (STs) were found, and 17/53 strains belonged to ST58, which was partially associated with serotype O8:H25 (Fig. 1).

Bacteriophage isolation and genomic analysis

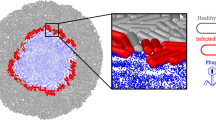

Seven phages were isolated from wastewater and 1 phage was isolated from cow slurry. Two phages were isolated against E. coli 824, two other phages against E. coli 814 and the last four against E. coli 819 (Fig. 2). All phages belong to the Caudoviricetes class, which are double-stranded DNA tailed phages. Five different genera were identified via BLASTn and phage AI: Phapecoctavirus, Gamaleyavirus, Drulisvirus, Tequatrovirus and Mosigvirus. The genome size ranged between 42,674 and 169,529 bp. The GC content ranged from 35.41 to 51.15%. The in silico phage AI model predicted lytic phages with a level of confidence between 93.88% and 97.74%. However, the genome annotation revealed the presence of genes encoding a phage anti-repressor protein and an integrase in the phage vB_EcoP_ULIVPec3Lys (ULIVPec3Lys) which was reclassified as lysogenic. All other phages were exempt of genes associated with lysogeny, as well as virulence and resistance genes. All phages presented high similarities to existing E. coli phages when the nucleotides were blasted (BLASTn) (Supplementary Table S1). Based on the in silico phage AI model and the morphology of related phages, the morphologies of all isolated phages were predicted to be Myoviruses, except for the two Phapecoctavirus which were predicted to be Podoviruses. Phages ULIVPec7-8-9-10 were isolated against the same strain (E. coli 819), belong to the Tevenvirinae subfamily and are phylogenetically related: ULIVPec7-8-10 belong to the Tequatrovirus genus, whereas ULIVPec9 belong to the Mosigvirus genus. ULIVPec1 and ULIVPec2 are also related and were isolated against the same strain (E. coli 824). ULIVPec3Lys and ULIVPec4 were isolated against the strain E. coli 814 but belong to distinct families (Fig. 2).

Host range of bacteriophages and correlation with bacterial serotypes

The phages lysed between 1.89% and 33.96% of the 53 strains from our collection. A total of 29/53 E. coli were not lysed by any phage. ULIVPec3Lys and ULIVPec4 presented the narrowest host range, whereas ULIVPec2 presented the broadest one. The results were clustered according to the bacterial serogroup and the phage genus (Fig. 1). ULIVPec1 and 2 lysed the same strains of serogroup 8 but ULIVPec2 had a wider host range. ULIVPec7-8–9-10 lysed several serogroups and had similar host ranges. In contrast to Tequatrovirus phages, the Mosigvirus phage ULIVPec9 did not lyse serogroups O24 and O113 (Fig. 1). The detailed host range is presented in the Supplementary Table S2.

Receptor-binding protein determination

Regarding Tevenvirinae (ULIVPec7-8-9-10), a distinct multiple alignment was performed for all phages with their 4 most homologous phages in the NCBI databases, based on the E value (Supplementary Table S2). Genomic analysis highlighted four different genes encoding the long tail fiber (LTF): a proximal subunit, 2 hinge connectors and a distal subunit, followed by a chaperone. The multiple alignment allowed the identification of low-identity regions that were compatible with RBPs at the C-terminal region of the LTF distal subunit and in the short tail fiber (STF) (Supplementary Figure S1). Both proteins were related to RBPs and depolymerase activity according to the predictive models used. The protein structure of the last 223 amino acids of the LTF distal subunit was predicted and showed a folded trimer with a needle-like shape. The structure of the STF revealed a linear conformation terminating at a tip that contained a receptor-binding domain, preceded by a β-helical structure (Fig. 3). The LTF needle and STF structures of the related phages were also predicted and aligned with the isolated phages to determine the normalized root-mean-square deviation (RMSD100) between pairs of structures. The mean RMSD100 values of the related LTF needle and STF were respectively 28.14 (sd = 16.66) and 10.21 (sd = 4.61) (Fig. 4).

Predicted structure of newly isolated Tevenvirinae receptor binding proteins (RBPs) and structure alignments. RBPs of Tevenvirinae were identified in the short tail fiber (STF) and the needle of the long tail fiber (LTF). The complete predicted structures of the STF and LTF needle were obtained with Alphafold and are depicted in a gradient from red to blue, representing the N-terminal to the C-terminal region. (a) Straight trimer predicted structure of the STF. (b) The structure of the LTF involves a proximal subunit (light blue), two connectors (yellow) and a distal subunit (orange). The needle of the distal subunit include a knob, a stem and a tip, which is the receptor. The predicted structure of the needle is a folded trimer. (c) Alignment of the STF C-terminal region for the isolated Tevenvirinae. A beta-helical structure (red square) was observed in the structure. (d) Alignment of the LTF tip for the isolated Tevenvirinae.

Temperature and pH stabilities

All phages were stable from 25 °C till 45 °C after 1 h of incubation. At 60 °C, 4/8 phages showed a decrease of at least 2 log plaque-forming units (PFU)/mL, while the remaining phages were inactivated (Fig. 5A). All phages were stable at pH values ranging from 4 to 10, and ULIVPec4 was stable at a pH of 12, although a tenfold decrease (Fig. 5B).

Phage stability at different temperatures and pH values. (a) Phage titers on a logarithmic scale of plaque-forming units/mL (log PFU/mL) after 1 h of incubation at temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 60 °C. (b) Phage titers in log PFU/mL after 1 h of incubation at 37 °C at pH values ranging from 2 to 12. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

Stability of phages in milk

All the data were normally distributed. The one-way ANOVA analysis showed significant titer difference between groups (inoculum, 6 h incubation in raw milk, 6 h incubation in heat-treated (HT) milk) for phages ULIVPec2 (p = 0.01), ULIVPec3 (p = 0.01) and ULIVPec8 (p = 0.0005). The Bonferroni’s multiple comparison exhibited a significant lower titer in HT milk in comparison to the control group for the same 3 phages (p = 0.0036, p = 0.0036, p = 0.0009; alpha = 0.016). A higher titer was observed in raw milk in comparison to HT milk for phage ULIVPec8 (p = 0.0002, alpha = 0.0016). For the 5 remaining phages, no difference in titer was observed in the different groups (Fig. 6).

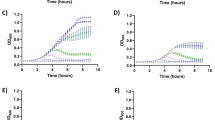

In vitro efficacy of phages in milk

The multiplicity of infection (MOI) of phages for optimal replication was 0.01 (Supplementary Figure S2). This MOI was used as an inoculum in milk samples. Phages led to a significant bacterial decrease (p = 6.58e-7) regardless of the type of milk. The random effect of phages contributed little to the variance (variance = 0.08019, sd = 0.2832), while the residual variance was higher (variance = 1.00990, sd = 1.0049). The bacterial decrease was sometimes below the limit of detection (BLD) of 333 CFU/mL. Only samples inoculated with ULIVPec4 showed a decrease in the bacterial titer (BLD) after 1 h of incubation. In raw, HT and UHT milk, a bacterial decrease BLD occurred at 3 h post-inoculation for respectively, 7/8, 8/8 and 5/8 phages but bacterial regrowth occurred 2 h later for 4, 6 and 3 phages, respectively (Fig. 7). An interaction between the phage treatment and the incubation time was highlighted (p < 2e-16 after 3 and 5 h of incubation). Despite bacterial regrowth, multiple comparisons revealed a significant phage effect on the bacterial reduction at all time points, with an enhancing effect over time. After 1 h of incubation, the bacterial reduction was significant but moderate (raw milk: 7.25 vs 5.78, p < 0.0001; HT milk: 7.35 vs 6.68, p = 0,021; UHT milk: 7.45 vs 6.56, p = 0.0025). In contrast, after 3 and 5 h of incubation, a greater reduction was observed, with differences exceeding respectively 6 and 8 log units (p < 0.0001 for all milk types).

In vitro efficacy of phages in milk. Bacterial titrations on a logarithmic scale of colony-forming units/mL (log PFU/mL) over incubation time. BLD = below limit of detection. Dotted lines = control group (bacteria in milk); solid lines = treatment group (bacteria + phage in milk); Blue = UHT milk; Orange = HT milk; Green = raw milk. Error bars represent the standard deviation. The limit of detection was set at 333 CFU/mL, and values BLD were assigned as half of the limit.

Two unexpected values were excluded from the data: one data for ULIVPec1 in raw milk after 1 h of incubation and one data for ULIVPec9 in UHT milk after 1 h of incubation. The two remaining data points from the triplicate were kept.

Discussion

Although no specific E. coli pathotype is exclusively associated with mastitis, the fact that our strains were isolated from bovine mastitis was important to take into account their virulence traits required to colonize and multiply in the udder, while escaping the innate immune system5. The diversity of the collection was confirmed with the serotype and ST profiles. This is opposed to other infections caused by E. coli, where predominant types are prevalent, such as serotype O80:H2, which is associated with ST 301 and is responsible for diarrhea and hemolytic and uremic syndrome in children20. However, some serogroups and STs were predominant in our collection as already reported for STs 10, 58 and 88, which were also identified among bovine mastitis strains21. These STs could be likely linked to virulence traits required for intramammary infection.

To standardize milk composition, raw milk free from contamination and samples from a unique farm were used for the in vitro studies. Indeed, the low SCC suggested the absence of mastitis and a determined bacterial concentration was manually inoculated into the sample. The purpose of comparing the stability and lytic activity of phages in raw milk with those in HT and UHT milk was to determine whether different heat-treatments and homogenization process influenced the results. Indeed, in certain conditions, proteins associated with milk-fat globules and agglutination of the strains can inhibit phage efficacy in raw milk, preventing bacterial reduction22,23. The heat-treatment of milk inactivated the heat-sensitive components that may interact with the phages. However, no significant effect of the milk type was highlighted on the bacterial reduction. This positive outcome could be linked to phage characteristics and agglutination properties that depend on the bacterial species.

The in vitro assessment of phage efficacy demonstrated a significant reduction in bacterial titer compared to the control. By modeling the phages as a random effect, the variance and standard deviation suggested that the observed variation in bacterial reduction occurred largely within phage measurements rather than between phages. Although bacterial regrowth was observed for 3/8 phages, the incubation time of phages significantly reduced bacterial titers compared to the control. The observed bacterial reduction was sometimes below the limit of detection (< 333 CFU/mL) which was caused by the titration technique. This explains why bacterial regrowth was observed even if no bacteria were titrated at the previous timepoint. Zhang and colleagues reported complete bacterial reduction after 1 h of incubation without regrowth in UHT milk when the phage PH444 targeting E. coli was used24. The regrowth observed in our study could be linked to bacterial resistance to phages, which is common and can occur even after a few hours’ incubation25. To avoid this phenomenon, an association of phages and antibiotics are typically used, which has shown synergistic effects in human treatments26. Moreover, a recent study highlighted that the use of Klebsiella phage cocktails has shown positive results in raw milk, possibly because of virulence trade-offs27. However, even with the use of cocktails, their study highlighted bacterial regrowth following an undetectable bacterial level in raw milk after 144 h at 5–9 °C and 9 h at 25 °C. In our study, samples were inoculated at a biological temperature of 37 °C, which facilitates bacterial and phage multiplication and thus resistance. Finally, the low MOI used in our study was optimal for phage replication but may not be ideal for bacterial reduction, which could promote resistance. In therapy, bacteriophage-insensitive mutants can be an obstacle. A recent study28 involving difficult-to-treat human infections treated with bacteriophages reported phage resistant bacteria in 7/16 patients. They observed that increasing the MOI led to a better lytic activity, until a certain concentration where bacterial regrowth appeared sooner and more frequently. In vitro antibiotic synergy was demonstrated in 90% of the patients, as well as antibiotic re-sensitization and reduced virulence in certain strains. This highlights the complexity of the phage-bacteria interaction, suggesting that efficacy cannot be assessed based solely on resistance.

In this study, the milk did not come from mastitis cases, which shows a different composition: it contains immune components (somatic cells), a different pH, and an unknown bacterial strain at an undetermined concentration. To stimulate an immune response without inducing infection, LPS infusion in the teat before milking could be performed. Based on the stability results, the increased pH of milk during mastitis should not affect the phage stability. The in vitro efficacy of phages for intramammary use should be evaluated under the most representative conditions of the mammary gland, including incubation of raw mastitis milk at 37 °C.

Additional in vitro models such as MAC-T cells should be used to further investigate the effects of phages on the mammary epithelium and the effects of the immune response. Preliminary in vivo studies in Galleria mellonella and mice could be performed to evaluate the survival rate after bacterial infection29 and assess the effect of phage treatment on murine mammary glands30. If successful, these phages could be administered intramammarily to cows with mastitis once the causative bacterial strain is isolated and its susceptibility to the phages is confirmed.

As the narrow host range of the isolated phages may be a challenge, part of the host specificity was investigated by studying RPBs of the Tequatrovirus and Mosigvirus phages. Interestingly, these phages were isolated against the same bacterial strain (E. coli 819), suggesting a similar adsorption mechanism. Indeed, analyses highlighted that these two genera belong to the Tevenvirinae subfamily, which has a LTF needle used as primary receptor for reversible attachment to surface proteins such as OmpC, Tsx and FadL or LPS when the first are not available19. This is followed by a detachment of the STF from the baseplate, which irreversibly attaches to the LPS inner core16. Our predicted STF structure showed a beta-helical structure, which might be associated with enzymatic activity17 and could participate in peptidoglycan degradation prior to DNA injection.

The structure alignment of RBPs outlined the main finding of our analysis, where respective low and high identities between the LTF needle and STF were calculated, suggesting that the host specificity is mainly linked to the needle conformation rather than the STF conformation.

The observed RBP conformation changes caused by genomic mutations could have considerable effects on host specificity, since a single amino acid change in the tip of the tail fiber can change the host range31. The type of Tevenvirinae receptors is consistent with the lack of association between the host range and the serogroup, as explained above. Indeed, some serogroups were lysed by particular phages, but all strains of a unique serogroup were not necessarily lysed. This is opposed to other subfamilies in which the phages attach to the O-antigen17. Different attachment mechanisms are involved depending on the subfamily. Moreover, homologous phages exhibiting different host ranges display overall genomic similarity but low sequence identity in their RBPs, whereas phages with identical host ranges may have divergent genomes but share highly conserved RBP sequences (Supplementary Table S3). Genomic database studies can provide valuable information for identifying the attachment mechanisms, as realized for the BASEL collection19. Similarly, the attachment specificities of Tevenvirinae characterized in this study could be transposed to related phages in other collections. Analyzing the host range with related bacterial species causing bovine mastitis could be performed to evaluate if other bacteria could be lysed by our phages.

The in silico phage AI model predicted lytic cycles for the phage ULIVPec3Lys, which presented an integrase and an anti-repression protein. Interestingly, phages belonging to the same genus were also predicted to be lytic in the literature32,33. It has been suggested that lytic phages could be derived from temperate phages by deletion and rearrangements in the lysogeny module34. Detailed annotation should be performed to avoid incorrect classification of the phage replication cycles. Moreover, only opaque lysis was described in the host range of this phage, which can indicate a temperate phage. Accurate determination of the replication cycle and verification of the absence of virulence and resistance genes are crucial for ensuring the safety of bacteriophages intended for therapeutic use.

In conclusion, 8 phages were isolated against E. coli strains responsible for mastitis. In vitro studies in raw milk demonstrated the stability of the phages and their ability to decrease the bacterial titer. However, resistance rapidly occurred and could be bypassed by a higher MOI and the use of a phage cocktail. A cocktail could also broaden the host range to target natural infections and delay bacterial regrowth. Indeed, the presence of 2 RBPs on Tevenviridae were associated with a diversity in the host range. A specific and reversible attachment by the LTF is followed by an irreversible and less specific attachment by the STF. Unfortunately, the bacterial receptors were not identified, but this could be resolved with an automated docking model that would show the interaction of the RPB on its host. Targeted knockout of the identified receptors could then validate their essential role by impairing phage adsorption. Further strategies should be implemented to minimize resistance, and characterization of resistant strains should be conducted to elucidate the mechanisms responsible for the bacterial adaptation and to evaluate the resulting fitness trade-off.

Materials and methods

Bacterial collection

Fifty-three strains were isolated between 2017 and 2023 from bovine mastitis originating from independent farms, except for the strain 821 and 835, 843 and 845, 836 and 848. Fifty strains were isolated from the Regional Animal Health and Identification Association (ARSIA, Wallonia) and 3 strains were isolated in the Fundamental and Applied Research in Animal Health (FARAH) bacteriology laboratory in 2023. Fifty strains were isolated in Belgium, 2 in Luxembourg and 1 in Germany (Table). Milk samples analyzed at ARSIA were spread on Columbia agar with sheep blood (ThermoFischer Scientific, USA) and Gassner agar (ThermoFischer Scientific, USA), and identified with MALDI-TOF (Bruker, USA). Three new strains were isolated in Walloon farms from cows diagnosed with mastitis by spreading milk samples on Mac Conkey agar (VWR, Belgium). Lactose positive colonies were further identified with API 20E galleries (bioMérieux, France). The identity of all 53 strains was confirmed on Coliform Extra Selective (ES) agar (Merck Millipore, USA) and with an indole test. The phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility to beta-lactams was assessed by the disk diffusion method using Mueller-Hinton agar (Becton Dickinson, Erembodegem, Belgium) and SIRscan Discs (i2a, France) (Table 1). Inhibition diameters were compared to the veterinary breakpoint of the French Society of Microbiology (CASFM-vet) (V1.0, 2022) and to the breakpoint of the European Committee of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (V12.0) if no CASFM-vet data were available.

Bacteriophage isolation

Phages were isolated with the enrichment method, as described in the literature with a few modifications35. Five different wastewater samples were collected in the surroundings of Liège (Belgium) in March 2023 and 1 slurry sample was collected in a Walloon farm during the same period. The slurry sample was tenfold diluted in sterile water and all samples were centrifuged (9,500 g, 10 min) and filtered at 0.2 μm. Five mL of each environmental sample were mixed with an equal volume of 2-times concentrated Luria Bertani (LB) broth (Merck Millipore, USA) supplemented with 1 mM of MgSO4 and CaCl2 (Merck Millipore, USA), as well as 100 µl of E. coli strains 814, 824 or 819 (OD600 = 0.3). Growth controls were prepared identically, except that PBS (Oxoid, UK) replaced the environmental sample. All samples were incubated at 37 °C. A decrease in turbidity in the environmental samples compared to the controls indicated phage replication. These samples were further filtered, and three-times subcultured on enriched LB agar by transplanting single identified lysis plaques in 200 µl of TN buffer (Tris 10 mM (Merck Millipore, USA), NaCl 150 mM (Merck Millipore, USA), pH 7.5). Pure clones were amplified to reach at least 10e8 plaques-forming units (PFU)/mL by adding the phage to enriched LB broth inoculated with the bacterial host. The lysate samples were then incubated overnight at 37 °C, centrifuged and filtered at 0.2 μm.

Bacterial genomic sequencing and genome analysis

Genomic DNA of the bacterial strains was extracted via a NucleoSpin® Microbial DNA Mini Kit (Machery-Nagel, Germany). The DNA concentration and purity were measured by NanoDrop (Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Sequence libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT DNA preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using half-volume reaction. DNA was sequenced with the NovaSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) to generate paired-end reads of 2 × 150 bp. Reads were assembled via SPAdes (v3.9.0).

Bioinformatic analysis were performed using the following pipelines of the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (https://www.genomicepidemiology.org) with default parameters: SerotypeFinder 2.0.1, VirulenceFinder 2.0.5, MLST 2.0 and CSI Phylogeny 1.4. The maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was processed with FigTree (v1.4.4).

Bacteriophage genomic sequencing and genome analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted as previously described36. The DNA concentration and purity measures, the library construction, the sequencing and the assembly were performed as described for the bacterial sequencing. The nucleotide similarities were assessed with BLASTn (National Library of Medicine, USA; https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Taxonomy and morphology of the phages were predicted with phage AI (https://app.phage.ai) and confirmed by comparing them with related phages from BLAST. Gene structure and functional annotation were performed with VIGOR 4 via BV-BRC (3.32.13a) (https://www.bv-brc.org). Certain protein functions were assessed with BLASTp (National Library of Medicine). A proteomic tree based on the genome taxonomical system was obtained using VIPtree (v4.0) (https://www.genome.jp/viptree).

Bacteriophage specificity

To determine the potential RPBs of Tevenvirinae phages, the genomes of their 5 highest homologous phages, based on the lowest expected hits (E values) from BLASTn, were investigated (Supplementary Table S1). A Multiple Alignment of the selected phages was performed using fast Fourier transform (MAFFT) in Geneious Prime 2024.0.7 (https://www.geneious.com). Regions with low identities and located in the tail region were suspected to be potential RBPs. Specific models such as Phage Depolymerase Finder (Galaxy Version 0.1.0, https://galaxy.bio.di.uminho.pt) and Phage RBP detect (v3)36 were used to refine the selection. The selected RBPs were compared to the literature16,17,37 and the structures of the proteins were modeled using AlphaFold238. For each protein, the 3D structure with the highest confidence score was selected, aligned and visualized with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 3.0 Schrödinger, LLC) and the NGLViewer R package (v1.3.4). Finally, the RMSD score was calculated with the rmsd function of the R package bio3d (v.2.4.5). This RMSD was normalized (Carugo and Pongor)39to become size independent. In the calculation of the normalized RMSD, the number of equivalent amino acids was obtained by aligning the amino acid sequences of the monomers of the proteins using “pairwise alignment” function of the pwalign R package (v.1.2.0). After alignment, the number of non-gaps positions was counted and multiplied by three (as the compared proteins are trimers) to obtain the number of equivalent amino acids.

Bacteriophage host range

Using the 53 strains from the bacterial collection, the host range of bacteriophages was determined by the spot test method adapted from Navez et al.40. For each phage, drops of 4 µL were spotted in triplicate on enriched LB agar with bacterial overlay (OD600 = 0.3). The plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C and the lysis plaques were scored as follows: confluent lysis, semi-confluent lysis, opaque lysis, countable lysis plaques, no lysis.

Optimal multiplicity of infection (MOI)

The MOI that produced the highest phage titer was determined as described by Li and Zhang41, with few modifications. Samples containing 5 mL of enriched LB broth were inoculated with 100 µL of phages at 10e6 PFU/mL and 100 µL of bacteria at a concentration ranging from 10e3 to 10e8 CFU/mL. Samples were incubated at 37 °C during 3.5 h and titrated. Titration consisted of triplicate 10-fold dilutions of phages in PBS, followed by 3 µL spots of each dilution on enriched LB agar covered by the host bacteria (OD600 = 0.3). After overnight incubation, plaques were counted, and the titer was calculated in PFU/mL. The MOI of the sample with the highest titer was selected for in vitro studies.

Temperature and pH stabilities

Temperature and pH stability were performed as described in the literature, with few modifications40.

Temperature stability was assessed by incubating 1 mL of phage lysate (ultrafiltered phages in enriched LB at a concentration of approximately 10e8 PFU/mL) at different temperatures (25 °C, 37 °C, 45 °C, and 60 °C).

For pH stability, 100 µL of 10e9 PFU/mL phage lysate were diluted in 900 µL of PBS at different pH values (2, 4, 7.4, 10, and 12). All the samples were incubated for 1 h and subsequently titrated in triplicate.

Milk samples

To select cows with minimal risk of mastitis (SCC < 2 × 10e5 cell/mL), monthly analysis of the SCC of each cow and a California mastitis test (CMT) were performed before sterile sampling. Half of the sample was stored at 4 °C, while the other half was heat-treated (HT) at 70 °C for 35 min and immediately stored at 4 °C. To ensure the absence of bacterial contamination, 100 µL of raw and HT milks were spread on LB and Mac Conkey agar. UHT whole milk (3.6% fat) was purchased from a local supermarket (Carrefour, Belgium).

Stability of phages in milk

A total of 0.5 mL of each phage at a known titer was added to 5 mL of raw or HT milk and the phage concentration was assessed after 6 h of incubation at 37 °C.

In vitro assessment of phage efficacy

For each phage, 100 µL of the phage (10e6 PFU/mL) and its bacterial host (10e8 CFU/mL) were incubated at the previously determined optimal MOI of 0.01 in 5 mL of raw, HT and UHT milk. The bacterial inoculum was titrated and bacterial titrations of the samples were performed at 1, 3 and 5 h of incubation with agitation at 37 °C. The control group consisted of the same milk samples inoculated with 100 µL of bacteria. All titrations were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses of the phage stability in milk were performed on GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA, www.graphpad.com). The normality of the data was investigated with Shapiro-Wilk and D’Agostino and Pearson tests. A one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons were performed to investigate the stability of the phages.

Regarding the in vitro assessment of phage efficacy, all analyses were performed with RStudio (RStudio Team (2025.09.0). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston; http://www.rstudio.com). A linear mixed-effects model was performed using the lme4 and lmerTest R packages. The normality of residuals was investigated using quantile-quantile plots and histograms of residuals. Following model fitting, a three-way ANOVA was performed with Satterthwaite’s method and multiple comparisons were conducted using estimated marginal means (emmeans R package). Values below the limit of detection (BLD) were considered as half of the limit of detection, which corresponded to log 2.2214 CFU/mL.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or Supplementary Table S4. Complete genome of the phages are deposited in the GenBank database with the following accession numbers: SAMN49823483 (vB_EcoM_ULIVPec1), SAMN49823484 (vB_EcoM_ULIVPec2), SAMN49823485 (vB_EcoP_ULIVPec3Lys), SAMN49823486 (vB_EcoP_ULIVPec4), SAMN49823487 (vB_EcoM_ULIVPec7), SAMN49823488 (vB_EcoM_ULIVPec8), SAMN49823489 (vB_EcoM_ULIVPec9), SAMN49823490 (vB_EcoM_ULIVPec10).

References

Hogeveen, H., Steeneveld, W. & Wolf, C. A. Production diseases reduce the efficiency of dairy production: A review of the results, methods, and approaches regarding the economics of mastitis. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 11, 289–312 (2019).

Hogan, J. & Smith, K. L. Managing environmental mastitis. Veterinary Clin. North. America: Food Anim. Pract. 28, 217–224 (2012).

Krishnamoorthy, P. et al. An Understanding of the global status of major bacterial pathogens of milk concerning bovine mastitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis (Scientometrics). Pathogens 10, 545 (2021).

Sepúlveda-Varas, P., Proudfoot, K. L., Weary, D. M. & Von Keyserlingk, M. A. G. Changes in behaviour of dairy cows with clinical mastitis. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 175, 8–13 (2016).

Goulart, D. B. & Mellata, M. Escherichia coli mastitis in dairy cattle: Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment challenges. Front. Microbiol. 13, 928346 (2022).

Suojala, L., Kaartinen, L. & Pyörälä, S. Treatment for bovine Escherichia coli mastitis – an evidence-based approach. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 36, 521–531 (2013).

World Health Organization. WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. https://www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed (2017).

Laxminarayan, R. et al. Antibiotic resistance—the Need Global Solutions 13, 1057–1098 (2013).

Comeau, A. M. et al. Exploring the prokaryotic virosphere. Res. Microbiol. 159, 306–313 (2008).

Salmond, G. P. C. & Fineran, P. C. A century of the phage: past, present and future. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 777–786 (2015).

Kortright, K. E., Chan, B. K., Koff, J. L. & Turner, P. E. Phage therapy: A renewed approach to combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Cell. Host Microbe. 25, 219–232 (2019).

Teng, F. et al. Efficacy assessment of phage therapy in treating Staphylococcus aureus-induced mastitis in mice. Viruses 14, 620 (2022).

Korhonen, H., Marnila, P. & Gill, H. S. Milk Immunoglobulins and complement factors. Br. J. Nutr. 84, 75–80 (2000).

Drobni, P., Naslund, J. & Evander, M. Lactoferrin inhibits human papillomavirus binding and uptake in vitro. Antiviral Res. 64, 63–68 (2004).

Seifu, E., Buys, E. M. & Donkin, E. F. Significance of the lactoperoxidase system in the dairy industry and its potential applications: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 16, 137–154 (2005).

Nobrega, F. L. et al. Targeting mechanisms of tailed bacteriophages. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 760–773 (2018).

Pas, C., Latka, A., Fieseler, L. & Briers, Y. Phage tailspike modularity and horizontal gene transfer reveals specificity towards E. coli O-antigen serogroups. Virol. J. 20, 174 (2023).

Labrie, S. J., Samson, J. E. & Moineau, S. Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 317–327 (2010).

Maffei, E. et al. Systematic exploration of Escherichia coli phage–host interactions with the BASEL phage collection. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001424 (2021).

Mainil, J. et al. Emerging hybrid shigatoxigenic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli serotype O80:H2 in humans and calves. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. e00011-25. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00011-25 (2025).

Nüesch-Inderbinen, M. et al. Molecular types, virulence profiles and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli causing bovine mastitis. Vet. Rec Open. 6, e000369 (2019).

Gill, J. J., Sabour, P. M., Leslie, K. E. & Griffiths, M. W. Bovine Whey proteins inhibit the interaction of Staphylococcus aureus and bacteriophage K. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101, 377–386 (2006).

O’Flaherty, S., Coffey, A., Meaney, W. J., Fitzgerald, G. F. & Ross, R. P. Inhibition of bacteriophage K proliferation on Staphylococcus aureus in Raw bovine milk. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 41, 274–279 (2005).

Zhang, H. et al. Isolation and characterization of a relatively broad-spectrum phage against Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 206, 197 (2024).

Antoine, C. et al. K1 capsule-dependent phage-driven evolution in Escherichia coli leading to phage resistance and biofilm production. J. Appl. Microbiol. 135, lxae109 (2024).

Van Nieuwenhuyse, B. et al. Bacteriophage-antibiotic combination therapy against extensively drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection to allow liver transplantation in a toddler. Nat. Commun. 13, 5725 (2022).

Yoo, S. et al. Designing phage cocktails to combat the emergence of bacteriophage-resistant mutants in multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiol. Spectr. 12, e01258–e01223 (2023).

Pirnay, J. P. et al. Personalized bacteriophage therapy outcomes for 100 consecutive cases: a multicentre, multinational, retrospective observational study. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 1434–1453 (2024).

Laforêt, F. et al. In vitro and in vivo assessments of two newly isolated bacteriophages against an ST13 urinary tract infection Klebsiella pneumoniae. Viruses 14, 1079 (2022).

Ngassam-Tchamba, C. et al. In vitro and in vivo assessment of phage therapy against Staphylococcus aureus causing bovine mastitis. J. Global Antimicrob. Resist. 22, 762–770 (2020).

Taslem Mourosi, J. et al. Understanding bacteriophage tail fiber interaction with host surface receptor: the key blueprint for reprogramming phage host range. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 12146 (2022).

Alexyuk, M. S. et al. Complete genome sequence of a Gamaleyavirus phage, lytic against avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Microbiol Resour. Announc 11, e00896–e00822 (2022).

Morozova, V. et al. Isolation and characterization of a novel Klebsiella pneumoniae N4-like bacteriophage KP8. Viruses 11, 1115 (2019).

Lucchini, S., Desiere, F. & Brüssow, H. Comparative genomics of Streptococcus thermophilus phage species supports a modular evolution theory. J. Virol. 73, 8647–8656 (1999).

Antoine, C. et al. In vitro characterization and in vivo efficacy assessment in galleria Mellonella larvae of newly isolated bacteriophages against Escherichia coli K1. Viruses 13, 2005 (2021).

Boeckaerts, D., Stock, M., De Baets, B. & Briers, Y. Identification of phage receptor-binding protein sequences with hidden Markov models and an extreme gradient boosting classifier. Viruses 14, 1329 (2022).

Hu, B., Margolin, W., Molineux, I. J. & Liu, J. Structural remodeling of bacteriophage T4 and host membranes during infection initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, (2015).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with alphafold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Carugo, O. & Pongor, S. A normalized root-mean-spuare distance for comparing protein three-dimensional structures. Protein Sci 10, 1470–1473 (2001).

Navez, M. et al. In vitro effect on piglet gut microbiota and in vivo assessment of newly isolated bacteriophages against F18 enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). Viruses 15, 1053 (2023).

Li, L. & Zhang, Z. Isolation and characterization of a virulent bacteriophage SPW specific for Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis of lactating dairy cattle. Mol. Biol. Rep. 41, 5829–5838 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Support Unit for Research and Teaching – Educational and Experimental Farm (Care-FEPEX, ULiège, Belgium), the Intermunicipal Association for Flood Protection and Wastewater Treatment of the Municipalities of the Province of Liège (AIDE, Liège, Belgium), Dr Célia Pas and Dr Fanny Laforêt for the scientific discussion, and Prof. Etienne Thiry for the language revision.

Funding

This program benefited from the financial support of Wallonia in the frame of a BioWin’s Health Cluster and Wagralim’s Agri-food Innovation Cluster program (Vetphage).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: T.D. and D.J.; Formal analysis: D.J., T.C., C.T.; Investigation: D.J., C.T., T.C.; Methodology: D.J., C.T., T.C., A.C.; Resources: S.M.; Supervision: T.D., H.T.; Writing: D.J. and T.D.; Review and editing: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jacob, D., Céline, A., Thomas, C. et al. Host-specificity and therapeutic potential of novel Escherichia coli-targeting bacteriophages for bovine mastitis control. Sci Rep 15, 41071 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25008-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25008-1