Abstract

Smoking is both a cause of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and is an important reason for its rising prevalence. However, there is a lack of studies predicting smoking cessation specifically in patients with OSA. This study aimed to identify the factors linked to smoking cessation by examining and comparing the clinical characteristics of current smokers and former smokers with OSA. Eligible adults with a diagnosis of OSA and who were smokers (n = 504) were enrolled in the study. Data on demographics, PSG results, and clinical information were collected. Participants were categorized into current smokers and former smokers based on their smoking status. Logistic regression was used to analyze factors associated with smoking cessation and Cox proportional hazards regression to evaluate the interactions among these factors. Among all patients with OSA included in the study, 69.0% were current smokers, while 31.0% were former smokers. Compared to current smokers, former smokers were generally older, had a longer duration of OSA, exhibited a higher proportion of severe OSA, had more smoking pack-years and a longer smoking duration, a higher BMI, AHI, and ODI, and a lower MSaO2. Logistic regression analysis revealed that smoking cessation was positively associated with factors such as age, disease duration, AHI, BMI, various clinical manifestations, and comorbidities, but negatively associated with MSaO2. The Cox proportional hazards regression model indicated that among the factors related to smoking cessation, OSA severity interacted significantly with hyperuricemia, metabolic syndrome, obesity, and lacunar infarction (all P < 0.05). The factors related to smoking cessation identified in this study should be emphasized in interventions aimed at quitting smoking in OSA patients. Addressing these factors may help prevent the exacerbation of OSA and enhance patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a respiratory syndrome caused by the collapse of the upper airway during sleep1. OSA is associated with a variety of diseases and complications, such as coronary heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, dyslipidemia, and cognitive impairment2,3,4. The clinical manifestations of OSA include drowsiness, snoring, waking up at night, apnea, reduced attention span and open mouth breathing, which often affect the life and work of OSA patients5. OSA has several risk factors, with smoking being a key contributor to both the development and worsening of the condition. Zeng et al. found a significant association between smoking and the occurrence of OSA6. Among OSA patients, compared with non-smokers, moderate to severe OSA is more common among smokers, and the AHI and oxygen saturation decline index are higher. Furthermore, the duration of smoking was significantly correlated with the severity of OSA7. Smoking can cause changes in sleep structure. Jaehne et al. reported that compared with non-smokers, smokers have less sleep time, longer sleep latency, more rapid eye movement sleep, and increased sleep apnea and leg movement8. Smoking can damage the neuromuscular protective reflexes of the upper airway. In animal models, smoke exposure led to a greater decrease in the respiratory rate due to laryngeal irritation and more apnea. So far, no direct reports of damage to the upper airway neuromuscular reflexes during sleep after smoke exposure have been found in humans9. Smoking often induces inflammatory responses and causes upper respiratory tract inflammation, which may increase the risk of OSA. In patients with moderate and severe OSA, an increase in the thickness of the lamina propria of the uvula mucosa was found, and only in smokers did the histology of the uvula mucosa show significant changes7.

Smoking cessation is a key measure for the prevention or treatment of OSA. Chen et al. found that age, pack-years, and BMI were identified as factors promoting smoking cessation in patients with asthma10. Pataka et al. reported that quitting smoking can reduce apnea and hypopnea index (AHI) in OSA patients11. However, there is currently limited data on smoking cessation in OSA patients. In this study, we aimed to discover the clinical characteristics of current and former smokers with OSA in order to identify the key factors driving smoking cessation.

Patients and methods

Study participants and definitions

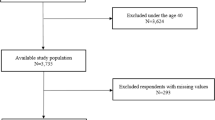

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (Ethical Code: LYF2023-059), all participants signed an informed consent form and all experiments were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Initially, we included 951 OSA patients diagnosed in the sleep laboratory at the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (Hunan, China) between January 2021 and March 2024. OSA was diagnosed by polysomnography (PSG) according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline, with AHI ≥ 5 events/h12. The severity of OSA was defined by the AHI, with an AHI of 5–14 events/h for mild OSA, an AHI of 15–29 events/h for moderate OSA, and an AHI of ≥ 30 events/h for severe OSA12. All enrolled patients were at least 18 years of age. The non-smokers were defined as participants who had never smoked or had smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Smokers were defined as those who smoked continuously for more than 10 pack-years10. The former smokers were defined as participants who had quit smoking for at least six months prior to the study. Patients who had no history of smoking, were less than 10 pack-years, and were younger than 18 years old were excluded. A detailed description of the flow diagram for recruiting OSA patients can be found in Fig. 1.

Data collection

After the written informed consent was collected, the subjects’ age, gender, duration of illness and smoking status were recorded. The duration of illness was defined as the time from the onset of OSA-related symptoms (such as snoring at night, apnea, daytime fatigue, drowsiness, etc.) in patients to the diagnosis of OSA in the hospital. Height and weight were measured and body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Meanwhile, the results of PSG tests (e.g., AHI, mean oxygen saturation [MSaO2], oxygen desaturation index [ODI]) were recorded.

Patient selection

A total of 504 patients were included in this study (including 156 former smokers and 348 current smokers), and 447 patients were excluded (139 patients lacked registration records of smoking status, 100 patients who refused to participate in the study, 80 patients who never smoked, 95 patients who smoked less than 10 pack years, and 33 patients were younger than 18 years old).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 26.0 software (IBM Corp.) was used for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were described as the mean and standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables were expressed as the number (percentage). The student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test, and the chi-square test were used to determine the differences between the two groups. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) of each adjustment. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression was used to calculate each adjusted hazards ratio (HR). A P value < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographic and sociological characteristics of 504 participants, including 348 smokers and 156 former smokers. The mean age was 47.87 ± 11.78 years for current smokers and 56.43 ± 12.79 years for former smokers (Table 1). There were significant differences in age, OSA duration, severity of OSA, occupation, BMI, AHI, MSaO2, and ODI between current and former smokers. Compared to current smokers, former smokers were older, had longer OSA duration, more severe OSA, higher smoking pack-years, longer smoking duration, higher BMI, AHI, and ODI, and lower MSaO2. Among occupations, a higher percentage of clerks are current smokers compared to former smokers. Detailed information on participant characteristics is shown in Table 1.

Clinical manifestations of the two groups

Table 2 shows the clinical manifestations of the two groups of patients. The incidence of hypomnesia, inattention, palpitations, gasping, hemoptysis, weakness, chest tightness, polydipsia, diuresis, and thirst was significantly higher in former smokers compared to current smokers (P < 0.05; Table 2). There was no significant difference in the incidence of other clinical symptoms between the two groups.

Concomitant diseases of the two groups

Table 4 shows the concomitant diseases of the two groups. The incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypoxemia, asthma, bronchiectasis, hypertension, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, fatty liver, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, obesity, gout, metabolic syndrome, lacunar infarction, arteriosclerosis in lower extremities, carotid atherosclerosis, cerebral arteriosclerosis, and old cerebral infarction was higher in former smokers compared to current smokers. Additionally, the incidence of COPD and hypoxemia in former smokers was predominantly severe, whereas in current smokers it was mainly mild (P < 0.05; Table 3). There was no significant difference in the incidence of other complications between the two groups.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with smoking cessation based on sociodemographic and clinical manifestations

In view of the differences in clinical characteristics between former smokers and current smokers, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors related to smoking cessation. According to sociodemographic characteristics, univariate analysis identified age, disease duration, severity of OSA, smoking years, pack-years, BMI, AHI, ODI and lower MSaO2 as factors associated with smoking cessation. Multivariate analysis further revealed that patients who were older (OR = 1.096, 95% CI = 1.047–1.147, P < 0.001), had a longer duration of OSA (OR = 1.049, 95% CI = 1.000–1.100, P = 0.049), more severe OSA (OR = 66.310, 95% CI = 25.337–173.540, P < 0.001), higher BMI (OR = 1.897, 95% CI = 1.476–2.439, P < 0.001), higher AHI (OR = 90.830, 95% CI = 27.202–303.292, P < 0.001), and lower MSaO2 (OR = 0.730, 95% CI = 0.668–0.797, P < 0.001) were more likely to quit smoking.

Regarding clinical manifestations, univariate analysis identified hypomnesia, inattention, gasping, weakness, chest distress, headache, polydipsia, diuresis, and thirst as related to smoking cessation. Multivariate analysis further revealed that patients with hypomnesia (OR = 3.693, 95% CI = 1.274–10.701, P = 0.016), inattention (OR = 6.071, 95% CI = 1.955–18.850, P = 0.004), gasping (OR = 2.953, 95% CI = 1.323–6.589, P = 0.008), weakness (OR = 5.251, 95% CI = 1.725–15.984, P = 0.004), chest distress (OR = 4.239, 95% CI = 1.845–9.741, P = 0.001), polydipsia (OR = 3.566, 95% CI = 1.666–7.633, P = 0.009), diuresis (OR = 5.263, 95% CI = 2.086–13.280, P < 0.001), and thirst (OR = 5.736, 95% CI = 1.412–19.857, P = 0.015) were more likely to quit smoking (Table 4).

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with smoking cessation based on concomitant diseases

According to concomitant diseases, univariate analysis identified COPD, hypoxemia, asthma, hypertension, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, fatty liver, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, gout, metabolic syndrome, obesity, lacunar infarction, arteriosclerosis in the lower extremity, carotid atherosclerosis, cerebral arteriosclerosis, and old cerebral infarction as factors associated with smoking cessation.

Multivariate analysis further revealed that patients with more severe hypoxemia (OR = 21.961, 95% CI = 9.248–121.450, P = 0.040), asthma (OR = 3.373, 95% CI = 1.312–8.671, P = 0.012), hypertension (OR = 5.978, 95% CI = 2.543–14.054, P < 0.001), coronary heart disease (OR = 8.572, 95% CI = 3.377–21.758, P < 0.001), myocardial infarction (OR = 4.219, 95% CI = 1.286–13.835, P = 0.018), diabetes (OR = 6.708, 95% CI = 2.806–16.039, P < 0.001), hyperlipidemia (OR = 8.242, 95% CI = 3.433–19.790, P < 0.001), hyperuricemia (OR = 5.829, 95% CI = 2.386–14.238, P < 0.001), metabolic syndrome (OR = 3.304, 95% CI = 1.391–7.850, P < 0.001), and arteriosclerosis in the lower extremity (OR = 2.844, 95% CI = 1.050–7.706, P = 0.040) were more likely to quit smoking (Table 5).

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis of the interaction between smoking cessation related factors

Consider that OSA is associated with comorbidities and there may be interactions. To further understand the effect of the interaction between OSA and comorbidities on smoking cessation, we assessed the interaction using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression after adjusting for age, sex, occupation, BMI, pack-years and years of smoking. Univariate analysis showed that patients with severe OSA combined with severe hypoxemia, asthma, hypertension, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, and metabolic syndrome were significantly more likely to quit smoking than those with severe OSA alone.

Multivariate analysis further revealed that patients with severe OSA combined with hypertension (HR = 1.967, 95% CI = 1.316–2.940, P < 0.001), diabetes (HR = 2.383, 95% CI = 1.584–3.585, P < 0.001), hyperlipidemia (HR = 1.752, 95% CI = 1.070–2.870, P = 0.026), hyperuricemia (HR = 2.359, 95% CI = 1.564–3.557, P < 0.001), and metabolic syndrome (HR = 1.775, 95% CI = 1.141–2.761, P = 0.011) were more likely to quit smoking compared to patients with severe OSA alone (Table 6).

Discussion

Smoking is a risk factor for several respiratory diseases, including obstructive sleep apnea. This cross-sectional descriptive study found differences between current and former smokers with OSA. Through logistic regression analysis, we identified independent factors that promote smoking cessation in OSA patients. Additionally, Cox proportional hazardss regression analysis revealed that OSA interacts with comorbidities, making patients more likely to quit smoking.

OSA was significantly associated with the risk of smokers compared to non-smokers13. Smoking behavior may contribute to the exacerbation of OSA by altering upper airway inflammation and causing sleep structure disorders14. Long uvula and enlarged tonsils are important causes of upper airway collapse of OSA. Kim et al. found that the lamina propria in uvula mucosa of OSA patients was significantly thickened in severe OSA. Meanwhile, compared with non-smokers, smokers increased the lamina propria thickness of uvula7. This study found that compared with current smokers, former smokers were older, had a longer OSA course, heavier OSA, more severe AHI, larger BMI and ODI, lower MSaO2, smoked longer, and had more pack-years of smoking. These findings suggest that most people with OSA continue to smoke until they develop obvious OSA symptoms themselves. Zeng et al. found an association between severe OSA, smoking years and smoking6. A cross-sectional study showed that in subjects with AHI > 50, smokers had a higher prevalence of OSA, and heavy smokers (≥ 30 pack-years) had a higher AHI than never smokers15. Casasola et al. showed that the amplitude and duration of the decrease of blood oxygen saturation during sleep in smokers was significantly higher than that in non-smokers, indicating that smoking caused more severe nighttime hypoxia16. In terms of occupation, it was found that the proportion of OSA patients who were clerks was higher, which may be related to the pressure of today’s society.

Pataka et al. found that quitting smoking can reduce AHI, which has guiding significance for the prognosis of OSA patients11. Long-term smoking cessation may be beneficial for improving sleep quality. Compared with those who have quit smoking, current smokers have much poorer sleep quality17. In addition, it has been found that the prevalence of sleep—disordered breathing among those who have quit smoking is not significantly higher than that among non-smokers18. Logistic regression analysis indicated that age, disease duration, OSA severity, AHI, ODI, BMI, and lower MSaO2 were factors associated with smoking cessation. Studies hava shown that old age and high BMI are strongly associated with OSA severity, which may encourage OSA patients to quit smoking10,19. OSA patients with high AHI are often accompanied by severe sleepiness, long disease duration, inattention, headache, and open mouth breathing, which affect the life and work of patients. Long-term smoking has been reported to increase the risk of airflow obstruction20. Studies have shown that the number of cigarettes smoked, the duration of smoking, and pack-years are important factors in quitting, and that the more cigarettes consumed and the longer people smoke, the more likely they are to quit21,22,23. Patients with a longer duration of disease may experience poorly controlled symptoms, which could motivate them to quit smoking. Chen et al. found that a longer disease duration increases the likelihood of smoking cessation8. Smoking cessation can lead to withdrawal symptoms, such as insomnia, increased wakefulness and sleep fragmentation, as well as reduced sleep time and sleep efficiency24. In addition, smoking cessation can also cause weight gain25. These factors can reduce the likelihood of successful smoking cessation and increase the relapse rate of smoking.

OSA is a risk factor for several diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, cognitive impairment, and digestive disease26,27,28,29. In this study, in OSA patients, we found that compared with current smokers, former smokers had a higher incidence of respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, digestive diseases, metabolic diseases, and neurological diseases, with corresponding increases in clinical manifestations. Naranjo et al. found that severe OSA could increase the hospitalization rate of COPD patients30. OSA causes abnormal blood pressure and metabolic disorders through hypoxia, endothelial cell dysfunction, inflammation and metabolic disorders, and promotes the occurrence of diseases31. Smoking can cause a series of physiological and pathological changes, such as oxidative stress and increased inflammation32. OSA disrupts sleep structure and causes repeated intermittent hypoxia during the night, leading to increased sympathetic nerve activity, heightened systemic inflammatory responses, and endothelial dysfunction33. Intermittent hypoxia also worsens metabolic dysfunction in obesity, contributing to increased insulin resistance and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease34. Additionally, oxidative stress associated with OSA promotes the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle, exacerbates inflammation, and accelerates arteriosclerosis35.

Studies have shown that quitting smoking is meaningful for preventing the occurrence and aggravation of many diseases36. Logistic regression analysis revealed that multiple comorbidities were associated with smoking cessation in patients with OSA, including hypoxemia, asthma, hypertension, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, diabetes, hyperuricemia, hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, and arteriosclerosis of the lower extremities. Studies have shown that the incidence of cardiovascular disease is significantly reduced after smoking cessation37. Among OSA patients, smokers showed higher triglyceride levels and lower high-density lipoprotein levels compared to non-smokers38. Smoking cessation is an effective measure to reduce lung function decline, while also improving the sensitivity of patients to bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids39. Smoking cessation can increase insulin sensitivity and improve pancreatic β-cell function impairment in diabetic patients40. OSA causes damage to the hippocampus through lack of oxygen, leading to cognitive impairment41. Mons et al. found that smoking was associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment, but that this risk decreased or even subsided after quitting20. A study found that smoking can promote an increase in uric acid. As tobacco exposure increases, the risk of hyperuricemia also rises. However, it is still unclear whether quitting smoking is beneficial for maintaining stable uric acid levels42. When OSA patients who smoke have these comorbidities, the probability of them quitting smoking may increase significantly.

Using Cox proportional hazardss regression, we found that OSA interacts with hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, and metabolic syndrome, and this interaction appears to facilitate smoking cessation in patients with OSA. Patients with OSA often have high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, and a higher BMI than those without OSA43. The main features of OSA, namely intermittent hypoxia, can promote insulin resistance caused by increased adipose tissue inflammation, pancreatic beta cell dysfunction, hyperlipidemia, and decreased triglyceride clearance, resulting in aggravation of metabolic syndrome or increased risk of its occurrence44. Studies have shown that smokers’ smoking behavior can be influenced by health scares, reducing the likelihood of heavy smoking (> 20 cigarettes/day) and increasing the likelihood of smokers quitting, and OSA patients with these comorbidities may be motivated to quit smoking due to concerns about their own health21.

There were some limitations of this study: (a) This is a cross-sectional descriptive study. Therefore, the results of this study can only provide data related to smoking cessation, and we cannot draw conclusions about the direction of causation. (b) At present, there are few reported factors related to OSA and smoking cessation, so the mechanism needs to be further explored.

Conclusions

In summary, among those who quit smoking, many quit smoking late and do not realize the need to quit until they have obvious clinical manifestations. The factors associated with smoking cessation identified in this study suggest that there are still clinical differences between current smokers and former smokers, and that these factors should be focused on in OSA cessation interventions or in people at high risk for OSA development to improve outcomes in OSA patients.

Data availability

The data used and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request; E-mail: ouyangruoyun@csu.edu.cn.

References

Joosten, S. A. et al. Assessing the physiologic endotypes responsible for REM- and NREM-based OSA. Chest 159(5), 1998–2007 (2021).

Labarca, G. et al. Efficacy of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and resistant hypertension (RH): Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 58, 101446 (2021).

Drager, L. F., Togeiro, S. M., Polotsky, V. Y. & Lorenzi-Filho, G. Obstructive sleep apnea: A cardiometabolic risk in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62(7), 569–576 (2013).

Martinez-Garcia, M. A., Sánchez-de-la-Torre, M., White, D. P. & Azarbarzin, A. Hypoxic burden in obstructive sleep apnea: Present and future. Arch. Bronconeumol. 59(1), 36–43 (2023).

Jackson, M. L., Howard, M. E. & Barnes, M. Cognition and daytime functioning in sleep-related breathing disorders. Prog. Brain Res. 190, 53–68 (2011).

Zeng, X. et al. Association between smoking behavior and obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nicot. Tob. Res. 25(3), 364–371 (2023).

Kim, K. S. et al. Smoking induces oropharyngeal narrowing and increases the severity of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 8(4), 367–374 (2012).

Jaehne, A. et al. How smoking affects sleep: A polysomnographical analysis. Sleep Med. 13(10), 1286–1292 (2012).

St-Hilaire M, Duvareille C, Avoine O, et al. Effects of postnatal smoke exposure on laryngeal chemoreflexes in newborn lambs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2010; 109(6): 1820–6.

Chen, Z. et al. Different clinical characteristics of current smokers and former smokers with asthma: A cross-sectional study of adult asthma patients in China. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 1035 (2023).

Pataka, A. et al. Varenicline administration for smoking cessation may reduce apnea hypopnea index in sleep apnea patients. Sleep Med. 88, 87–89 (2021).

Kapur, V. K. et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: An American academy of sleep medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin Sleep Med 13(3), 479–504 (2017).

Jang, Y. S., Nerobkova, N., Hurh, K., Park, E. C. & Shin, J. Association between smoking and obstructive sleep apnea based on the STOP-Bang index. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 9085 (2023).

Krishnan, V., Dixon-Williams, S. & Thornton, J. D. Where there is smoke there is sleep apnea: Exploring the relationship between smoking and sleep apnea. Chest 146(6), 1673–1680 (2014).

Hoflstein, V. Relationship between smoking and sleep apnea in clinic population. Sleep 25(5), 519–524 (2002).

Casasola, G. G. et al. Cigarette smoking behavior and respiratory alterations during sleep in a healthy population. Sleep Breath. Schlaf Atmung 6(1), 19–24 (2002).

McNamara, J. P. et al. Sleep disturbances associated with cigarette smoking. Psychol. Health Med. 19(4), 410–419 (2014).

Wetter, D. W., Young, T. B., Bidwell, T. R., Badr, M. S. & Palta, M. Smoking as a risk factor for sleep-disordered breathing. Arch. Intern. Med. 154(19), 2219–2224 (1994).

Zhang, Z., Wang, Y., Li, H., Ni, L. & Liu, X. Age-specific markers of adiposity in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 83, 196–203 (2021).

Mons, U., Schöttker, B., Müller, H., Kliegel, M. & Brenner, H. History of lifetime smoking, smoking cessation and cognitive function in the elderly population. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 28(10), 823–831 (2013).

Wang, Q., Rizzo, J. A. & Fang, H. Changes in smoking behaviors following exposure to health shocks in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15(12), 2905 (2018).

Godtfredsen, N. S., Prescott, E., Osler, M. & Vestbo, J. Predictors of smoking reduction and cessation in a cohort of danish moderate and heavy smokers. Prev. Med. 33(1), 46–52 (2001).

Kim, Y. J. Predictors for successful smoking cessation in Korean adults. Asian Nurs. Res. Korean Soc. Nurs. Sci. 8(1), 1–7 (2014).

Patterson, F. et al. Sleep as a target for optimized response to smoking cessation treatment. Nicot. Tob. Res. 21(2), 139–148 (2019).

Williamson, D. F. et al. Smoking cessation and severity of weight gain in a national cohort. N. Engl. J. Med. 324(11), 739–745 (1991).

Urbanik, D., Martynowicz, H., Mazur, G., Poręba, R. & Gać, P. Environmental factors as modulators of the relationship between obstructive sleep apnea and lesions in the circulatory system. J. Clin. Med. 9(3), 836 (2020).

Aron-Wisnewsky, J., Clement, K. & Pépin, J. L. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and obstructive sleep apnea. Metabolism 65(8), 1124–1135 (2016).

Light, M., McCowen, K., Malhotra, A. & Mesarwi, O. A. Sleep apnea, metabolic disease, and the cutting edge of therapy. Metabolism 84, 94–98 (2018).

Marchi NA, Solelhac G, Berger M, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea and 5-year cognitive decline in the elderly. Eur. Respir. J. 61(4) (2023)

Naranjo, M., Willes, L., Prillaman, B. A., Quan, S. F. & Sharma, S. Undiagnosed OSA may significantly affect outcomes in adults admitted for COPD in an inner-city hospital. Chest 158(3), 1198–1207 (2020).

Redline, S., Azarbarzin, A. & Peker, Y. Obstructive sleep apnoea heterogeneity and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 20(8), 560–573 (2023).

Badran, M. & Laher, I. Waterpipe (shisha, hookah) smoking, oxidative stress and hidden disease potential. Redox Biol. 34, 101455 (2020).

Monahan, K. D., Leuenberger, U. A. & Ray, C. A. Effect of repetitive hypoxic apnoeas on baroreflex function in humans. J. Physiol. 574(Pt 2), 605–613 (2006).

Iiyori, N. et al. Intermittent hypoxia causes insulin resistance in lean mice independent of autonomic activity. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 175(8), 851–857 (2007).

Lee, J. & Kang, H. Hypoxia promotes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through microRNA-mediated suppression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Cells 8(8), 802 (2019).

Patel, M. S. & Steinberg, M. B. In the clinic. Smoking cessation. Ann. Internal Med. 164(5), itc33–itc48 (2016).

Duncan, M. S. et al. Association of smoking cessation with subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA 322(7), 642–650 (2019).

Lavie, L. & Lavie, P. Smoking interacts with sleep apnea to increase cardiovascular risk. Sleep Med. 9(3), 247–253 (2008).

van Schayck, O. C. et al. Do asthmatic smokers benefit as much as non-smokers on budesonide/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy? Results of an open label study. Respir. Med. 106(2), 189–196 (2012).

Maddatu, J., Anderson-Baucum, E. & Evans-Molina, C. Smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes. Transl Res 184, 101–107 (2017).

Prabhakar, N. R., Peng, Y. J. & Nanduri, J. Hypoxia-inducible factors and obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Investig. 130(10), 5042–5051 (2020).

Kim, Y. & Kang, J. Association of urinary cotinine-verified smoking status with hyperuricemia: Analysis of population-based nationally representative data. Tob. Induc. Dis. 18, 84 (2020).

Geer, J. H. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 52(5), 1835–1838 (2021).

Giampá, S. Q. C., Lorenzi-Filho, G. & Drager, L. F. Obstructive sleep apnea and metabolic syndrome. Obesity Silver Spring 31(4), 900–911 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the voluntary patients involved in the study.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82100039, No. 82170039), the National Key Clinical Specialty Construction Projects of China, and the China Scholarship Council (No. 202406370116).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and design: ZC, RO; Methodology: BW, YS, YO; Data management: ZC, SG; Statistical analysis and interpretation: ZC, XX, RO; All authors contributed to drafting the original manuscript of important intellectual content and final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (Ethical Code: LYF2023-059), all participants signed an informed consent form.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Shang, Y., Wasti, B. et al. Differences in clinical features between current smokers and former smokers with OSA: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 41073 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25032-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25032-1