Abstract

Strain engineering of 2D heterostructures is pivotal for next-generation flexible electronics. Here, we investigate the straintronic and spintronic properties of MnO₂/SiC van der Waals heterostructures (vdWHs) using density functional theory (DFT). Our results reveal: (i) a strain-induced transition from Type-I to Type-II band alignment, (ii) emergence of topological signatures under tensile strain, and (iii) enhanced visible-light absorption. The MnO₂/SiC vdWH, with its intrinsic ferromagnetism (4.85 µB) and strain-tunable multitronic responses, offers a unique platform for spintronic and optoelectronic applications unattainable in conventional TMD-based systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Straintronics is an emerging field of research that focuses on improving the electronic properties of materials by applying controllable strain, thereby enhancing device performance and enabling the realization of new quantum states in condensed matter physics. The fundamental concept of straintronics is to induce mechanical deformation in materials to modify their band structure (BS), and consequently alter their electronic, optical, and magnetic properties. This makes them promising candidates for flexible electronic devices, sensors, and memory technologies1,2.

In recent years, a new direction in this field has involved the straintronics of van der Waals (vdW) materials, which have attracted significant attention due to their unique mechanical properties, such as high flexibility and strong resistance to strain3,4,5,6,7. Depending on the stacking structure of the layers, the applied strain in vdW materials can generally be categorized into two types: in-plane and out-of-plane. In the first case, the material is stretched along the two-dimensional (2D) plane, whereas in the second case, it is compressed perpendicularly to the plane8. Notably, in-plane strain has proven to be more effective for engineering the band structure of vdW materials.

The manipulation of band structures through in-plane strain was first demonstrated in graphene, and later extended to black phosphorus and transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs)9,10,11,12. For example, it has been reported that the band gap of monolayer MoS₂ undergoes a transition from direct to indirect under a tensile strain of approximately 1%13. Similarly, strain has been shown to effectively tune the band gap of black phosphorus, making it a valuable candidate for the design of functional electronic and optoelectronic devices10.

Synthesis of heterostructure (HSs) based on vdW compounds, as one of prevalent methos for manipulating their band gaps, has gained much interest in recent years because of the weak nature of vdW forces, good response to the mechanical deformations and wide range of applications14,15. For instance, Wei et al. showed that imposing strain on the HSs between TMDs: MoS2/ MoSe2, MoSe2/ MoS2, MoS2/ WSe2 and WSe2/ MoS2 would result in direct-indirect band gap transition as well as modification in the split between the bonding and antibonding states at symmetry k points. As a notable piont, strain would change the band alignment of these HSs by displacing the band edges. Recent advances in strain engineering of vdWHs focus on TMD-based systems (e.g., MoS₂/WS₂), where strain modulates bandgaps or induces indirect-direct transitions16,17,18. However, strain-induced topological transitions and magnetic responses in oxide/SiC heterostructures remain unexplored. For instance, while Wei et al.19 demonstrated strain-tunable band alignment in TMDs, our work reveals strain-driven topological signatures and spintronic functionality in MnO₂/SiC, enabling ‘multitronic’ behavior absent in conventional systems. While the combination of strain-driven topology, magnetism, and optoelectronics in oxide/SiC heterostructures remains unexplored, MnO₂/SiC is uniquely suited for this due to: (a) MnO2’s high Curie temperature (40 K) and strong spin-orbit coupling, (b) SiC’s robust mechanical stability, and (c) their lattice mismatch (< 5%), enabling efficient strain transfer. This synergy positions MnO₂/SiC as a promising candidate for multiferroic spintronic devices.

Depending on the band alignment profile, heterostructures (HSs) can be classified into three categories: type-I, type-II, and type-III. In type-I HSs, both the conduction band minimum (CBM) and the valence band maximum (VBM) reside in the same layer. As a result, when type-I HSs are illuminated, electrons and holes accumulate within a single layer. This configuration is not favorable for efficient charge-carrier separation but is highly suitable for applications such as lasers and light-emitting diodes (LEDs)20,21,22.

In contrast, type-II HSs exhibit spatial separation of photogenerated electrons and holes, which significantly enhances their efficiency and makes them excellent candidates for photovoltaic and photocatalytic applications23,24. The transition from type-I to type-II HSs is therefore an intriguing phenomenon and an important research direction for exploring the potential of van der Waals heterostructures (vdW HSs) in optical and electronic devices. Consequently, the search for two-dimensional (2D) materials capable of forming type-II HSs is actively ongoing, although only a limited number of reports have been published so far.

Recently, monolayer MnO₂ has been introduced as an intrinsic ferromagnet with a Curie temperature of about 40 K, which is comparable to the TCT_CTC of Mn-doped GaAs25,26,27,28,29. Moreover, it appears to be superior to other known magnetic monolayers due to its distinctive atomic arrangement and robust magnetic behavior. Interestingly, MnO₂ and SiC monolayers exhibit strong lattice compatibility, and inspection of their band structures predicts the formation of a type-I heterostructure (HS).

In this work, we investigate the effects of in-plane strain on the MnO₂/SiC van der Waals heterostructure (vdWH) using density functional theory (DFT) calculations. In addition to analyzing its electronic behavior and band alignment—which confirm its type-I nature—we also study the influence of biaxial strain on its electronic and optical properties. The MnO₂ monolayer is a strong ferromagnet, and when coupled with SiC, it may serve as a spin injector, providing a vdWH with potential for advanced magnetic and spintronic applications.

Applying tensile strain to this vdWH leads to two remarkable outcomes: (i) a transition from type-I to type-II alignment, and (ii) a shift of conduction levels toward the valence band, accompanied by the transformation of the Γ-point symmetry into a saddle shape. These findings indicate the possible emergence of topological behavior under strain.

Computational details and methods

All calculations were performed using the Wien2K package. For structural relaxation, the PBE-GGA functional30,31 was employed with a 12 × 12 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-mesh and an energy convergence criterion of 10⁻⁵ eV. Ionic forces were converged to < 0.01 eV/Å. Electronic properties were calculated using the HSE06 hybrid functional (α = 0.25, screening length ω = 0.2 Å⁻¹)32 with a 15 × 15 × 1 k-mesh and energy convergence of 10⁻⁶ eV. The DFT-D3 method corrected van der Waals interactions33, and a 20 Å vacuum layer prevented inter-slab coupling.

Results and discussion

Monolayers of MnO2 and SiC have the same lattice structure and very closed lattice constants with mismatch of about 5%. Derived amounts for their lattice constants are respectively \(\:{\text{a}}_{1}={\text{b}}_{1}=2.89\:\text{A}\text{˚}\) and \(\:{\text{a}}_{2}={\text{b}}_{2}=3.07\:\text{A}\text{˚}\), which display good agreement with previous reports25,34,35,36. Figure 1-a shows the top and side view of the MnO2/SiC HS. Separation between the two primary layers is \(\:1.93\:\text{A}\text{˚}\) and vdW switch has been hired for evaluation of the electronic and optical behaviors. Since the maximum amount of appliable strain on complex structures like vdWs has always been a challenging subject,

Applied to this vdWH was biaxial strain from − 10% untill 10%, as per \(\:S=\left(\frac{a-{a}_{^\circ\:}}{{a}_{^\circ\:}}\right)\times\:100\), being \(\:a\) and \(\:{a}_{^\circ\:}\) the relaxed and strained lattice constants, respectively.

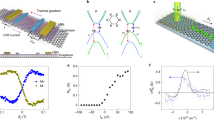

Monolayers of MnO₂ and SiC share the same lattice symmetry and exhibit very close lattice constants, with a mismatch of approximately 5%. The calculated lattice parameters are \(\:{\text{a}}_{1}={\text{b}}_{1}=2.89\:\text{A}\text{˚}\) for MnO2 and \(\:{\text{a}}_{2}={\text{b}}_{2}=3.07\:\text{A}\text{˚}\) for SiC, which are in good agreement with previous reports25,34,35,36. Figure 1a illustrates the top and side views of the MnO₂/SiC heterostructure (HS). The interlayer separation between the two primary layers is 1.93 Å. To evaluate the electronic and optical properties, van der Waals (vdW) corrections were incorporated.

Since determining the maximum applicable strain for complex structures such as vdW heterostructures (vdWHs) has always been a challenging issue, we applied biaxial strain in the range of − 10% to + 10%. The strain was defined as:

where a and \(\:{a}_{^\circ\:}\) are the strained and relaxed lattice constants, respectively.

Stability was inspected via binding energy represented in the following equation:

Wherein, \(\:{E}_{\text{M}\text{n}\text{O}2\text{}/\text{S}\text{i}\text{C}}\), \(\:{E}_{\text{M}\text{n}\text{O}2}\) and \(\:{E}_{\text{S}\text{i}\text{C}}\) stand for the total energy of MnO2/SiC vdWH, and that of MnO2 and SiC respectively. While biaxial strains of ± 10% exceed current experimental limits for vdWHs (typically ≤ 5%), computational exploration of extreme strains serves two purposes: (i) It identifies fundamental property trends (e.g., band alignment transitions, topological precursors) that guide targeted experiments, and (ii) It reveals critical strain thresholds for device design. To assess mechanical stability, we calculated the strain-binding energy curve (Fig. 1b). Negative binding energies showing no bond-breaking or structural collapse up to ± 10%. However, we note that experimental realization may require specialized substrates (e.g., piezoelectric materials) or nanoindentation techniques. It is perceivable that lowest value of \(\:{E}_{b}\) relates to the relaxed form (\(\:S=0\)), while for both tensile (negative) and compressive (positive) strains it exhibits an increasing trend. Moreover, the changes of total magnetic moment (\(\:{M}_{tot})\) (in Fig. 1b) is rapidly decreasing for tensile strains, but under the compressive condition, it represents a very mild growth.

In the first step, the electronic properties of the vdWH were examined through the calculated band structure and density of states (DOS) for both spin-up and spin-down channels (Fig. 1c and d). Due to the presence of the transition metal Mn with a half-filled d orbital, magnetic behavior is expected in this system. This expectation is confirmed by the calculated total magnetic moment \(\:{M}_{tot}\) of approximately \(\:4.85{\mu\:}_{B}\). As shown in Fig. 1c, within the GGA approximation, the vdWH exhibits a semimetallic character with a Dirac-type point at the Fermi level for the spin-down channel, while the spin-up channel behaves as a semiconductor with a band gap of about 2.01 eV. This electronic configuration suggests that the system could serve as a promising candidate for spintronic applications. In contrast, within the HSE06 approximation, the vdWH is found to be semiconducting for both spin channels, exhibiting direct band gaps of 1.21 eV and 3.20 eV for spin-up and spin-down states, respectively.

It should be declared that next calculations to extract physical quantities in the following, are based on the electronic states derived from HSE06 approximation. Remarkable is that band gap becomes wider more than doubled by spin flip, hence an external magnetic field could be applied for switching. Furthermore, with reference to Fig. 1d, high density of the electronic states are discernable in the energy range of \(\:-2\:\text{e}\text{V}\) to \(\:-7\:\text{e}\text{V}\) within the valence band, and so is hold in the opposite range of energy within the conduction band .It is worthy of note that electronic levels along the symmetry path of Γ and X tend to be saddle-like. The band structure content is quite reflected in the DOS plot, enriched by involving distinct contribution of the layers. It is worth mentioning that electronic states of MnO2 for up (down) spins have shifted below (above) the Fermi level, but no significant changes have occurred in the electronic feature of SiC. That reveals high sensitivity of the MnO2 layer to external field which brings it forth as a good magnetic switch. Our analysis on the orbital- projected band structure in Fig. 1(e, f) also shows that in two spin channels the CBM and VBM are predominantly contributed by the C atoms, confirming the desired type-I band alignment. Furthermore, the VBM and CBM are mainly from the localized Mn dz2, dyz and C pz orbitals (in spin up) and are from the localized O pz, Si pz and C pz orbitals (in spin dn) (Table 1).

(a) Top and side view of the MnO2/SiC vdWHS with arrows pointing to the biaxial in-plane strain. (b) Binding energy and total magnetic momentum vs. strain. (c) band structure in GGA approximation. (d) band structure and electronic DOS and (e, f) Orbital-projected band structures for spin up and down in HSE06 approximation (Fermi level is set to \(\:0\:\text{e}\text{V}\)).

Figure 2a and b illustrate the effect of applied strain on the electronic properties of the MnO₂/SiC vdWH. For the spin-up channel (Fig. 2a), relative to the Fermi level, the four nearest bands in the valence region are labeled sequentially as 1–4, while the three closest bands in the conduction region are similarly labeled. It can be clearly seen that under compressive strains of 0.04, 0.08, and 0.10, no significant changes occur, except that band 1 in the valence region becomes increasingly curved.

Also, for the tensile strain of -0.04 position and curvature of the graphs are very similar to those of the relaxed case (\(\:S=0\)) and none of importance occurs except from slight displacement of the conduction and valence bands towards the Fermi level and making the gap a bit narrower. However, under the tensile strains of -0.08 and − 0.1 an important event appears and conductive levels shift towards the valence zone, meaning that tensile strain of such orders would transform this vdWHS in spin up into a topological behavior. Noteworthy is the intensity of this shift, in that the bands 1 and 2 which early were in the energy regions of about \(\:2\:\text{e}\text{V}\) and \(\:5\:\text{e}\text{V}\), displace into the new regions of about \(\:-4\:\text{e}\text{V}\) and \(\:-3\:\text{e}\text{V}\). These levels are mostly belonged to the Mn-dz2 and C-pz orbitals and the pertaining electrons must each have consumed energies of about \(\:6\:\text{e}\text{V}\) and \(\:8\:\text{e}\text{V}\), respectively. More interesting is displacement of 4 aforementioned bands below the Fermi level towards energies less than \(\:-4\:\text{e}\text{V}\). This results are presented in Table 2.

Concerning down spins, as summarized in Fig. 2b, under the compressive strain of 0.04 the band gap accepts a mild reduction, but no significant change in the band structure configuration or location of the electronic levels is observed. This consequence is more substantial for higher degrees of compression, besides this phenomenon that gaps below the Fermi level get wider. Presence of filled levels in the valence area (\(\:-1\:\text{e}\text{V}\) to \(\:-2.5\:\text{e}\text{V}\)), gives hope that utilization of MnO2/SiC vdWH under compressive strain, could be convenient for optoelectronic and thermoelectric applications. This idea is reinforced by taking into account the dense aggregation of levels with high DOS below the Fermi level. Further, in the case of tensile strain, it is easily deduced that \(\:S=-0.04\:\)gives rise to no noticeable changes in comparison to \(\:S=0\:\)However, salient changes emerge when system is exposed to the greater orders, \(\:S=\) -0.08 and − 0.1 and thereby five conductive levels, from number 3 till 7, transform to the valence zone. Obviously, this shift, which in turn requires high amount of energy, signifies a topological behavior caused from vdW interaction between the MnO2 and SiC layers. The orbitals participating in this shift are mostly related to the pz, C-s and Si-pz. The magnetic moment (4.85 µB) primarily arises from Mn2+ (d3 configuration). Under tensile strain, the moment decreases to 4.22 µB (Table 2). This weakens superexchange interactions, as confirmed by the reduced exchange splitting in DOS (Fig. 1d).

While our DFT calculations cannot prove topology, the orbital-resolved band structures (Fig. 1e, f) and also Figs. 2a and b, show gap closure at Γ-point—a known precursor to topological transitions37,38 Future work should compute edge states or Chern numbers to validate these predictions. However, definitive confirmation requires calculation of Berry curvature or Zz invariants, which is beyond this study’s scope.

The VBM/ CBM shifts under strain and Zoomed insets at Γ-point for saddle-shaped dispersion for two spin up and down directions. (a) For spin up, four bands below the Fermi and 3 conduction bands above the fermi level have been marked by numbers 1–4 and 1,2 and 3, respectively. (b) For spin down, two valence bands below the Fermi level and nine conduction bands above the fermi level have been marked by numbers1,2 and 1–9, respectively. Fermi level is set to \(\:0\:\text{e}\text{V}\).

In the next step, optical absorption of the MnO2/SiC vdWH under strain, along the x (in-plane) and z (normal) directions was investigated and outcomes are depicted in Fig. 3a. The upper panel for z direction shows that absorption has in general a growing trend versus wavelenght, with an outstanding peak at the visible area. In addition, although a partly reduction appears around the UV edge, the curve regains its ascending figure against photons of higher energies. Referring to the lower panel.

A similar trend is observed along the x-axis, except that the absorption in this direction is generally weaker. It should be noted that in both directions, compressive strain reduces the optical absorption, whereas tensile strain significantly enhances it, particularly in the infrared (IR) and visible regions of the spectrum. For example, under a tensile strain of − 0.08, the absorption coefficients in the visible range along the z- and x-axes are approximately 1.5 and 2 times larger, respectively, than their unstrained values at \(\:S=0\). Evidently, the optimum tensile strain is − 0.08, since increasing its magnitude to − 0.10 results in a reduction of optical absorption. By comparing the absorption curves in Fig. 3 with the BSs in Fig. 2, it could be deduced that majority part of the absorbed incident radiation is due to the changes and shift of the mentioned electronic levels. In other words, travel of some electronic levels from conduction to valence territory, is followed by amplification in absorption of electromagnetic waves.

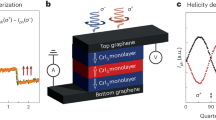

Portrayed in Fig. 3b is the band alignment of the MnO2/SiC vdWH for spin up and down. It is clear that both spin directions reveal the band alignment of type-I, since the valence and conduction edges of MnO2 monolayer are both between those of SiC monolayer. Calculated values of electron affinity (\(\:{{\upchi\:}}^{e}\)) belonging to the MnO2 and SiC monolayers, respectively turned out to be \(\:-2.10\:\text{e}\text{V}\) and \(\:-2.90\:\text{e}\text{V}\) for spin up, but \(\:-2.63\:\text{e}\text{V}\) and \(\:-2.90\:\text{e}\text{V}\) for spin down. Accordingly, conduction and valence band offsets (CBO and VBO) are easily derived in the order as \(\:0.269\:\text{e}\text{V}\) and \(\:0.458\:\text{e}\text{V}\) for spin up, while \(\:0.560\:\text{e}\text{V}\) and \(\:0.164\:\text{e}\text{V}\) for spin down. Inevitably, as soon as this vdWH is assembled, the electrons of MnO2 monolayer gain tendency to migrate towards SiC nearby.

A key aspect of this study is that the conduction band offset (CBO) undergoes a significant change when an external magnetic field is applied. This effect provides, for the spin-down channel, a more favorable voltage for electron-hole transport from MnO₂ to SiC. From an optical perspective, irradiation by an electromagnetic beam generates electron-hole pairs—particularly in the spin-down channel—between the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) of SiC. This, in turn, creates favorable conditions for the emission of photon pairs near the VBM and CBM of SiC.

Panels (a-b) and (c-d) of Fig. 4 display respectively the band structure and band alignment of the MnO2/SiC vdWH under biaxial strains from − 0.1 to 0.1 As clearly seen for both spin directions, width of the band gap increase by increasing the compressive strain (from 0.04 to 0.1), but decreases by increasing the amount of tensile strain (from − 0.04 to -0.1). Furthermore, by extending the tensile strain from − 0.04 to -0.1 CBM at the M, X and G points shifts downward (upward) for up (down) spins, whereas VBM is located at the Γ point for both spin directions. Notably, by enlarging the tensile strain, a displacement in the bands around the Fermi level, aimed at intersecting it, is observed. In the case of \(\:S=0\:\)edges of the conduction and valence bands are both caused from the MnO2 monolayer, but for intense values of tensile strain and displacement of the electronic levels, CBM would be due to the SiC monolayer. Besides, as reflected in Figs. 3c & d, the type of band alignment remains as relaxed (type-I) for all orders of compressive strains, while the tensile strains of great order (\(\:S\) = -0.08 and − 0.1), cause it to transform into type-II. This transformation is of great importance, since it results in more efficient separation and recombination of electron-holes, which is in turn a crucial parameter for photocatalytic, photovoltaic and optoelectronic activities. Compared to TMD-based vdWHs39,40,41,42,43, MnO₂/SiC offers three unique advantages: (i) intrinsic ferromagnetism enabling spin-filtering without external fields, (ii) strain-driven topological transitions absent in non-magnetic systems, and (iii) enhanced visible-light absorption (2× higher than MoS₂/WS₂ at 500 nm). These properties make MnO2/SiC a superior candidate for multifunctional ‘multitronic’ devices.

Conclusion

Within the framework of DFT studies, the band alignment, as well as the electronic and optical properties of the MnO2/SiC vdWH, were analyzed in both the relaxed state and under compressive and tensile strain. The system was found to be a ferromagnetic semiconductor with a total magnetic moment of 4.85 µB and direct band gaps of approximately 1.21 eV and 3.20 eV at the Γ point for spin-up and spin-down channels, respectively.

Its saddle-type type-I band alignment can be readily transformed into a type-II alignment under suitable tensile strain, wherein the VBM and CBM are localized on the MnO2 and SiC monolayers, respectively, rendering this vdWH suitable for photocatalytic applications. Interestingly, tensile strain induces a saddle-shaped deformation in the conduction band states and shifts them toward the valence region, suggesting the emergence of topological behavior under biaxial strain. Furthermore, the vdWH exhibits high optical absorption, particularly in the visible region and near the UV edge, which is further enhanced under tensile strain, highlighting its potential for optoelectronic applications.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Akinwande, D., Petrone, N. & Hone, J. Two-dimensional flexible nanoelectronics. Nat. Commun. 5 (1), 5678 (2014).

Çakıroğlu, O., Island, J. O., Xie, Y., Frisenda, R. & Castellanos-Gomez, A. An automated system for strain engineering and straintronics of 2D materials. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8 (1), 2201091 (2023).

Deng, S., Sumant, A. V. & Berry, V. Strain engineering in two-dimensional nanomaterials beyond graphene. Nano Today. 22, 14–35 (2018).

Dai, Z., Liu, L. & Zhang, Z. Strain engineering of 2D materials: issues and opportunities at the interface. Adv. Mater. 31 (45), 1805417 (2019).

Miao, T., Yeom, S., Wang, P., Standley, B. & Bockrath, M. Graphene nanoelectromechanical systems as stochastic-frequency oscillators. Nano Lett. 14 (6), 2982–2987 (2014).

Drissi, L. B., Sadki, K. & Kourra, M. H. Mechanical response of SiC sheet under strain. Mater. Chem. Phys. 201, 199–206 (2017).

Li, S. Y., Su, Y., Ren, Y. N. & He, L. Valley polarization and inversion in strained graphene via pseudo-Landau levels, Valley splitting of real Landau levels, and confined States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124 (10), 106802 (2020).

Miao, F., Liang, S. J. & Cheng, B. Straintronics with Van der Waals materials. Npj Quantum Mater. 6 (1), 59 (2021).

Yang, R. et al. Tuning optical signatures of single-and few-layer MoS2 by blown-bubble Bulge straining up to fracture. Nano Lett. 17 (8), 4568–4575 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Strain-modulated bandgap and piezo-resistive effect in black phosphorus field-effect transistors. Nano Lett. 17 (10), 6097–6103 (2017).

Ni, Z. H. et al. Uniaxial strain on graphene: Raman spectroscopy study and band-gap opening. ACS Nano. 2 (11), 2301–2305 (2008).

Farkous, M. et al. Strain effects on the electronic and optical properties of Van der Waals heterostructure MoS2/WS2: a first-principles study. Phys. E: Low-dimensional Syst. Nanostruct. 116, 113799 (2020).

Conley, H. J. et al. Bandgap engineering of strained monolayer and bilayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 13 (8), 3626–3630 (2013).

Zhu, T. et al. Highly mobile charge-transfer excitons in two-dimensional WS2/tetracene heterostructures. Sci. Adv. 4 (1), eaao3104 (2018).

Wang, F. et al. Tuning coupling behavior of stacked heterostructures based on MoS2, WS2, and WSe2. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 44712 (2017).

Nayak, D. & Thangavel, R. Insight into enhanced photocatalytic properties of a type-II MoS 2/ZnO heterostructure and tuning its properties and interfacial charge transfer by strain. New J. Chem. 47 (7), 3328–3340 (2023).

Nayak, D. & Thangavel, R. Strain modulated electronic and photocatalytic properties of MoS2/WS2 heterostructure: A DFT study. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 5 (1), 302–316 (2022).

Nayak, D. & Thangavel, R. Theoretical investigation of electronic and photocatalytic properties of a trilayer VdW MoS2/ZnO/WS2 heterojunction for overall water-splitting applications. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 7 (7), 2642–2652 (2024).

Kumar, A. et al. Fabrication of porous and visible light active ZnO nanorods and ZnO@ TiO 2 core–shell photocatalysts for self-cleaning applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25 (24), 16423–16437 (2023).

Amiri, M., Boochani, A. & Nia, B. A. Electronic, thermodynamic Stability, and band alignment behavior of the CoVSi/NaCl heterojunction. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 11 (11), 114004 (2022).

Özçelik, V. O., Azadani, J. G., Yang, C., Koester, S. J. & Low, T. Band alignment of two-dimensional semiconductors for designing heterostructures with momentum space matching. Phys. Rev. B. 94 (3), 035125 (2016).

Yeganeh, M., Boochani, A., Yari, A., Amiri, M. & Shahraki, A. T. The WS2/AlN heterostructure band alignment by semi-local functional and its optical properties by the Bethe-Salpeter approximation on top of GW calculations. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 148, 106772 (2022).

Peng, Q., Wang, Z., Sa, B., Wu, B. & Sun, Z. Electronic structures and enhanced optical properties of blue phosphorene/transition metal dichalcogenides Van der Waals heterostructures. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 31994 (2016).

Liao, J., Sa, B., Zhou, J., Ahuja, R. & Sun, Z. Design of high-efficiency visible-light photocatalysts for water splitting: MoS2/AlN (GaN) heterostructures. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118 (31), 17594–17599 (2014).

Kan, M., Zhou, J., Sun, Q., Kawazoe, Y. & Jena, P. The intrinsic ferromagnetism in a MnO2 monolayer. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4 (20), 3382–3386 (2013).

Liu, H. J. et al. A metal–insulator transition of the buried MnO2 monolayer in complex oxide heterostructure. Adv. Mater. 28 (41), 9142–9151 (2016).

Morinson-Negrete, J. D., Ortega-López, C. & Espitia-Rico, M. J. Effects of mono-vacancies of oxygen and manganese on the properties of the MnO2/Graphene heterostructure. Materials 15 (8), 2731 (2022).

Mo, Z. et al. Construction of MnO2/Monolayer g-C3N4 with Mn vacancies for Z-scheme overall water splitting. Appl. Catal. B. 241, 452–460 (2019).

Wang, R. Q., Lei, T. M. & Fang, Y. W. First-principles design of ferromagnetic monolayer MnO2 at the complex interface. Phys. Scr. 98 (6), 065960 (2023).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. J. P. R. Density functional theory (DFT). Phys. Rev., 136(1964), B864. (1964).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B. 46 (11), 6671 (1992).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118 (18), 8207–8215 (2003).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long‐range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27 (15), 1787–1799 (2006).

Rusho, M. A., Kanjariya, P., Rajiv, A., Suleman, A. D., Kareem, R. A., Abdulaali,H. S., Omran, A. A. Development of SiC monolayer for detection of SO3 and NF3 hazardous gases based on DFT calculations. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry, 1244, 115045. (2025).

Zhao, Z., Yong, Y., Zhou, Q., Kuang, Y. & Li, X. Gas-sensing properties of the SiC monolayer and bilayer: a density functional theory study. ACS Omega. 5 (21), 12364–12373 (2020).

Ataca, C., Sahin, H. & Ciraci, S. Stable, single-layer MX2 transition-metal oxides and dichalcogenides in a honeycomb-like structure. J. Phys. Chem. C. 116 (16), 8983–8999 (2012).

Drissi, L. B., Sadki, K., Kourra, M. H. & Bousmina, M. Strain-engineering of Janus SiC monolayer functionalized with H and F atoms. J. Appl. Phys., 123(18). (2018).

Hirahara, T., Otrokov, M. M., Sasaki, T. T., Sumida, K., Tomohiro, Y., Kusaka, S., Chulkov, E. V. Fabrication of a novel magnetic topological heterostructure and temperature evolution of its massive Dirac cone. Nat. commun., 11(1), 4821. (2020).

Din, H. U. et al. Rashba spin splitting and photocatalytic properties of GeC-M SSe (M = Mo, W) Van der Waals heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B. 100 (16), 165425 (2019).

Din, H. U., Idrees, M., Alam, Q. & Amin, B. Van der Waal heterostructure based on BY (Y as, P) and MX2 (M Mo, W; XS, se) monolayers. Appl. Surf. Sci. 568, 150846 (2021).

Ahmad, S. et al. Type-II Van der Waals heterostructures of GeC, ZnO and Al2SO monolayers for promising optoelectronic and photocatalytic applications. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 48 (65), 25354–25365 (2023).

Alam, Q., Sardar, S., Din, H. U., Khan, S. A., Idrees, M., Amin, B., Laref, A. A first principles study of a van der Waals heterostructure based on MS 2 (M = Mo,W) and Janus CrSSe monolayers. Nanoscale Adv.4(17), 3557–3565. (2022).

Din, H. U., Idrees, M., Rehman, G., Nguyen, C. V., Gan, L. Y., Ahmad, I., Amin,B. Electronic structure, optical and photocatalytic performance of SiC–MX 2 (M = Mo, W and X = S, Se) van der Waals heterostructures. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 20(37), 24168–24175. (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Amir Zelati: He calculated the Bandalignment properties and wrote the draft of the article .Jabbar Khodadadi: He made the structures and calculated the mini-position calculations.Halkawt Abdalqadir kh ahmed: He performed band structure calculations under pressure.Rusul Mohsin Moharib AlsarrayShe explain the mathematic relations and depicted the electronic calculations.Sarkut Ibrahim Mahmood: He performed the HSE calculations and collected the references.Khatereh SarvazadShe depicted the band-alignment diagrams and collected the references Farzad AhmadianHe calculated the relaxation of the structures and used from wandervale switch.Maliheh Amiri: She performed calculations of the density of electronic states and calculated the magnetic moment.Arash Boochani: The original idea for this project belongs to him and he wrote and edited the article. Arash Yari: He did the grammatical editing and drew the diagrams.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zelati, A., Khodadadi, J., Abdalqadir kh ahmed, H. et al. Straintronic and spintronic properties of MnO₂/SiC Van der Waals heterostructure: a DFT study. Sci Rep 15, 41319 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25061-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25061-w