Abstract

Broadband ultra-high resolution spectrometers require arc-second level grating positioning accuracy to achieve picometer to femtometer spectral resolution. Traditional control approaches exhibit significant limitations when confronting system nonlinearities, parameter uncertainties, and external disturbances. This work presents an adaptive PID control methodology integrating Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with Radial Basis Function (RBF) neural networks. The approach establishes a pitch axis dynamic model incorporating friction, gravitational effects, and transmission backlash, then implements an RBF network architecture enabling real-time parameter adaptation. An enhanced PSO algorithm performs global network parameter optimization, creating a dual-stage control framework combining “offline global optimization with online local adaptation.” Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves 0.7-1.0 arc-second angular positioning accuracy—representing substantial improvements in step response characteristics compared to conventional PID and RBF-PID controllers. Under ± 30% system parameter variations, the controller maintains excellent positioning performance with markedly reduced disturbance recovery times. External disturbance testing reveals a disturbance rejection ratio of -25.31 dB, with substantially diminished steady-state accuracy degradation. These findings validate the control strategy’s effectiveness for grating precision positioning applications, offering a novel solution for high-precision spectral measurement technology while providing valuable insights for other precision mechanical systems requiring arc-second level positioning accuracy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Broadband high-resolution spectrometers constitute critical optical measurement instruments in contemporary scientific research, serving indispensable roles in astronomical observations, atmospheric environmental monitoring, material characterization, and biomedical analysis1,2,3,4. Achieving simultaneous broadband coverage and high-resolution detection necessitates sophisticated scanning mechanisms: horizontal rotation enables spectral scanning across wide wavelength ranges, while vertical adjustment modifies grating diffraction orders to attain picometer to femtometer ultra-high resolution5,6. This dual-axis positioning requirement demands precision turntable mechanisms controlling grating orientation in two dimensions: the yaw axis manages large-range spectral scanning for broadband coverage, while the pitch axis executes fine angular adjustments for ultra-high resolution measurements7. Through coordinated dual-axis motion and multi-order diffraction optical design, the system achieves seamless integration of broadband and ultra-high resolution capabilities.

Escalating spectral resolution requirements impose increasingly stringent demands on grating angular positioning accuracy for precise spectral measurements, typically necessitating arc-second level or superior precision1. In high-precision spectral measurements, wavelength calibration accuracy correlates directly with system positioning accuracy. Research indicates that for UV-visible spectrometers, every 0.2 ppm laser wavelength measurement error may induce significant wavelength calibration deviations8. Such extreme precision requirements subject grating scanning mechanism control systems to multifaceted challenges: systems exhibit pronounced nonlinear characteristics including friction variations, gravitational influences, and transmission backlash; parameter uncertainties prove substantial, encompassing load inertia variations, friction coefficient drift, and motor parameter fluctuations; external disturbances such as temperature variations and vibrations impose non-negligible positioning accuracy impacts. These factors collectively constitute fundamental technical barriers to achieving arc-second level precision control.

Alternative approaches to nonlinearity handling in precision positioning have been explored in recent research. Output feedback bounded control methods utilizing Fuzzy Logic Systems have demonstrated effectiveness for addressing hysteresis nonlinearity and input constraints in piezoelectric-driven micropositioning stages through adaptive fuzzy approximation combined with auxiliary design systems9. While both FLS-based methods and the proposed PSO-RBF-PID approach target nonlinearity compensation in precision systems, the methodologies differ in several key aspects. FLS employs rule-based linguistic models with IF-THEN fuzzy rules, whereas RBF networks utilize Gaussian basis functions with continuous parameter space, offering advantages in high-precision numerical optimization. FLS typically relies on adaptive laws with manual rule design, while the PSO-RBF framework performs systematic global optimization of all network parameters offline. Furthermore, FLS methods excel in handling hysteresis and input saturation in piezoelectric systems, while the proposed approach specifically addresses the combined effects of friction nonlinearity, gravitational torque variation, and transmission backlash in rotational positioning systems. The complementary nature of these approaches suggests that precision positioning control benefits from method selection tailored to specific system characteristics: FLS for hysteretic systems requiring linguistic rule interpretability, and RBF-PSO for rotational systems demanding arc-second precision with globally-optimized continuous compensation.

Dual-axis turntable precision positioning systems extend far beyond spectrometer applications, demonstrating broad utility across numerous high-technology domains. In space technology, satellite attitude control and optical remote sensing systems demand arc-second level pointing accuracy for high-resolution Earth observation10; laser communication systems require ultra-high precision beam pointing control to ensure long-distance communication quality11; high-precision radar and radio telescope antenna systems necessitate accurate angular positioning for weak signal capture12; in precision manufacturing, high-end optical component processing equipment and semiconductor lithography systems require ultra-high precision rotational positioning13,14. Wang et al.15 emphasized in their 2024 review that as scientific instruments and high-end equipment advance toward micro-nano scales, angular measurement and control technology has emerged as a common critical factor constraining frontier technology development across multiple fields. These applications similarly emphasize angular positioning accuracy rather than extremely high dynamic response speeds or complex trajectory tracking capabilities, thus presenting common requirements for precision control algorithms.

Traditional control methods encounter obvious limitations when addressing dual-axis turntable precision positioning tasks. Classical PID control, despite widespread application due to its simplicity and stability, struggles with system nonlinearity and parameter variations owing to fixed parameters16. Shi et al.17 demonstrated that even nonlinear PID approaches show performance improvements, yet control accuracy degrades significantly under parameter uncertainty or external disturbances. Regarding fuzzy PID methods, Mohindru18 noted that rule design heavily depends on expert experience with complex parameter adjustment calculations, limiting high-precision scenario applications. Recently, intelligent control technologies have provided novel approaches for such problems. Kim19 proposed model-free intelligent PID control based on RBF neural networks, compensating time-delay errors through RBF networks combined with adaptive robust terms, significantly enhancing system adaptability. Liu et al.20 introduced a PSO-NMPC control strategy for mining loader path tracking in 2024, improving nonlinear model predictive controller performance through particle swarm optimization, with experimental results showing 68.9–89.7% improvements in maximum absolute lateral deviation, demonstrating PSO effectiveness in precision control optimization. Deep reinforcement learning applications in path planning and MIMO systems have also achieved breakthroughs, with research showing DRL can generate high-quality paths through environment interaction learning, exhibiting significant advantages over traditional methods in handling complex nonlinear systems and real-time decision-making21. Nevertheless, existing research presents two limitations: (1) RBF-PID controllers exhibit strong initial parameter dependence and easily converge to local optima; (2) global optimization algorithms possess high computational complexity with insufficient real-time performance22,23.

Addressing these challenges, this research proposes a composite control architecture integrating Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with Radial Basis Function (RBF) neural networks, targeting arc-second level precision positioning for spectrometer grating scanning mechanisms. Kashyap and Parhi24 demonstrated PSO’s excellent performance in optimizing PID control parameters, while Zhu et al.25 confirmed RBF neural networks’ superior adaptability to nonlinear system dynamics. Building upon these foundations, the method’s innovation manifests in three key aspects with specific technical contributions.

First, establishing a dual-stage optimization architecture combining offline global optimization with online adaptive adjustment. Unlike existing RBF-PID approaches that rely solely on online learning and often converge to suboptimal solutions due to poor initialization, our method employs PSO to comprehensively optimize all RBF network parameters including centers, widths, and weights offline before deployment. This pre-optimized network then serves as the foundation for online adaptive tuning, ensuring the controller starts from a near-globally-optimal state.

Second, designing enhanced convergence mechanisms specifically tailored for precision positioning applications. The dynamic learning rate strategy adapts based on real-time error magnitude, while the improved inertial weight function systematically balances exploration and exploitation across the optimization process, significantly improving convergence efficiency compared to fixed-weight PSO approaches.

Third, developing a comprehensive simulation framework that systematically incorporates practical nonlinearities including Stribeck friction characteristics, transmission backlash with hysteresis effects, gravitational torque variations, and multi-frequency environmental disturbances. This framework enables rigorous validation of controller robustness under realistic operating conditions.

Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method successfully improves system positioning accuracy to 0.7–1.0 arc-second levels, representing a 76% improvement over traditional PID controllers, while maintaining stable high-precision control performance under ± 30% system parameter variations and external disturbance conditions. These achievements provide effective technical support for grating precision positioning and offer novel approaches for control strategy optimization in similar precision mechanical systems.

Dual-axis turntable system analysis and modeling

System structure and operating principle

The spectrometer dual-axis turntable system serves as the critical actuating mechanism for achieving broadband high-resolution spectral measurements, with its structural design and dynamic characteristics directly influencing spectral measurement precision and stability. This section provides systematic analysis of the overall system architecture, transmission characteristics, and operating principles, establishing the theoretical foundation for subsequent control algorithm development.

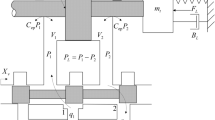

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the mechanical structure adopts a “yaw-pitch” configuration, enabling precise rotational positioning of the grating about the Z-axis (yaw) and X-axis (pitch). The yaw axis handles large-range spectral scanning (typically ± 30°), while the pitch axis performs fine angular adjustments (typically ± 10°). Coordinated motion of both axes constitutes a precise grating positioning system. The experimental setup utilizes a grating measuring 20 cm × 8 cm with approximately 0.32 kg mass, mounted on the pitch axis.

The drive system employs a combination of DC servo motors and harmonic reducers, featuring low backlash and high rigidity characteristics. The pitch axis incorporates a harmonic reducer with reduction ratio n = 20:1, where the transmission relationship between motor and load satisfies:

where \(\:{\theta}_{\text{L}}\) and \(\:{\theta}_{\text{m}}\) represent angular displacements at load and motor ends, respectively; \(\:\omega _{\text{L}}\) and \(\:\omega _{\text{m}}\) denote angular velocities at load and motor ends, respectively; \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{L}}\) and \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{m}}\) represent torques at load and motor ends, respectively; \(\:\text{n}\) is the reduction ratio; and \(\:\eta\) is the transmission efficiency (approximately 0.85). In precision systems, transmission backlash (approximately 0.02°) constitutes a critical factor affecting positioning accuracy.

Position detection employs high-precision magnetoelectric encoders with 0.001° resolution, whose measurement equation can be expressed as:

where \(\:{\delta }_{\text{backlash}}\) represents transmission backlash error and \(\:{\delta }_{\text{sensor}}\) denotes sensor error. Both factors jointly influence system control accuracy.

From spectral measurement principles, a strict nonlinear relationship exists between grating angle and wavelength. According to the grating diffraction equation: \(\:\text{d}\left({sin\alpha +sin \beta}\right) = \text{m}\lambda\), where \(\:\text{d}\) is the grating constant, \(\:{\alpha }\) is the incident angle, \(\:{\beta }\) is the diffraction angle, \(\:\text{m}\) is the diffraction order, and \(\:\lambda\) is the wavelength. For visible-near-infrared scanning in the 300–1100 nm range, the nonlinear relationship between grating angle \(\:{\theta}_{\text{i}}\) and wavelength \(\:{\lambda}_{\text{i}}\) is:

This nonlinear relationship imposes high-precision requirements on the control system, particularly in regions demanding high wavelength resolution.

System dynamic characteristics are primarily influenced by gravitational imbalance and coupled inertial effects. The gravitational torque can be expressed as:

where \(\:\text{m}\) is the grating mass (approximately 0.32 kg), \(\:\text{g}\) is gravitational acceleration, \(\:\text{l}\) is the distance from center of mass to rotation axis (approximately 0.067 m), and \(\:\theta\) is the pitch angle. Additionally, dynamic coupling exists between yaw motion and the pitch axis:

where \(\:{\text{I}}_{\text{y}\text{aw}}\) is the yaw axis moment of inertia, \(\:\text{L}=0.15\text{m}\) represents the effective coupling arm length defined as the distance from the yaw axis to the pitch axis center of rotation, \(\:{\dot\omega }_{\text{yaw}}\) and \(\:\omega _{\text{y}\text{aw}}\) denote the yaw angular acceleration and velocity respectively, and \(\:{\theta}_{\text{pitch}}\) is the pitch angle. This coupling effect is particularly significant during rapid scanning processes, where Coriolis forces and centrifugal forces generate additional torques on the pitch axis when the yaw axis operates at high angular velocities, affecting positioning accuracy.

Comprehensive analysis reveals that the pitch axis control system confronts three challenges: nonlinear characteristics (particularly gravitational and friction nonlinearities), parameter uncertainties, and external disturbances. These characteristics constitute fundamental problems for subsequent control algorithm design and serve as the basis for validating intelligent control algorithm superiority.

Pitch axis mathematical model and transfer function

Pitch axis system dynamic modeling

The precise mathematical model of the spectrometer dual-axis turntable pitch axis control system forms the foundation for control algorithm design. Based on motor drive system physical characteristics and mechanical transmission principles, this section establishes a comprehensive pitch axis dynamic model encompassing electrical and mechanical components.

The pitch axis comprises a DC servo motor, harmonic reducer, and grating load. The electrical component’s dynamic characteristics can be represented by the following differential equation:

where \(\:{\text{L}}_{\text{a}}\) is the armature inductance (2.8 × 10−3 H), \(\:{\text{R}}_{\text{a}}\) is the armature resistance (2.6 Ω), \(\:{\text{i}}_{\text{a}}\left(\text{t}\right)\) is the armature current, \(\:{\text{u}}_{\text{a}}\left(\text{t}\right)\) is the input voltage, \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{e}}\) is the back-EMF constant (0.056 V s/rad), and \(\:\omega _{\text{m}}\text{(}\text{t}\text{)}\) is the motor angular velocity.

The relationship between motor output torque and current is:

where, \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{t}}\) is the torque constant (0.056 N·m/A). For brushless DC motors, typically \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{t}} = {\text{K}}_{\text{e}}\).

The mechanical system dynamics equation must consider rotational inertia, friction damping, and external loads:

where, \(\:{\text{J}}_{\text{eq}}\) is the equivalent moment of inertia, \(\:{\text{B}}_{\text{eq}}\) is the equivalent damping coefficient, \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{L}}\left(\text{t}\right)\) is the load torque, \(\:\text{n}\) is the reduction ratio, and \(\:\eta\) is the transmission efficiency. The equivalent moment of inertia considering the reducer is calculated as:

where, \(\:{\text{J}}_{\text{m}}\) is the motor rotor inertia (\(\:3.5\times 10^{-5} kg m^{2}\)) and \(\:{\text{J}}_{\text{L}}\) is the load inertia (\(\:2.8 \times 10^{-4} kg m^{2}\)).

The load torque \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{L}}\left(\text{t}\right)\) primarily comprises gravitational torque \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{g}}\left(\text{t}\right)\) and frictiona torque \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{f}}\left(\text{t}\right)\):

Gravitational torque can be linearized for small angles as:

Friction torque includes static friction, Coulomb friction, and viscous friction components:

where, \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{s}}\) is the static friction torque (0.012 N m), \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{c}}\) is the Coulomb friction coefficient (0.008 N·m), \(\:{\text{B}}_{\text{L}}\) is the load-side viscous friction coefficient (\(3.4 \times 10^{-4} N m s/rad\)), and \(\:\omega _{\text{L}}\) is the load angular velocity.

System transfer function derivation

To obtain the system transfer function, the differential equations undergo Laplace transformation. Considering that the motor electrical time constant (τe = La/Ra ≈ 1.1 ms) is significantly smaller than the mechanical time constant, inductance effects can be neglected, simplifying the electrical component to:

Substituting Eq. (8) into the mechanical dynamics equation and considering the transmission relationship between load and motor: \(\:{\Omega }_{\text{m}}\left(\text{s}\right) = {\Omega }_{\text{L}}\left(\text{s}\right) = {\Omega }_{\text{m}}\left(\text{s}\right)/\text{n}\), \(\:{\Theta }_{\text{L}}\left(\text{s}\right) = {\Theta }_{\text{m}}\left(\text{s}\right)/\text{n}\), and rearranging yields:

Substituting respective coefficient values and simplifying, the transfer function from motor angle to input voltage becomes:

For analysis convenience, the transfer function is standardized to second-order system form:

where, \(\:\text{K}\:=\:\text{0.0865}\) is the system gain, \(\:\tau =\:\text{0.0538}\text{s}\) is the time constant, and \(\zeta = ~0.939\) is the damping ratio. This indicates near-critical damping with minimal oscillatory characteristics.

Recognizing that nonlinear factors in actual systems, such as static friction, transmission backlash, and load uncertainty, prevent theoretical models from comprehensively reflecting system dynamic characteristics, this research adopts the following transfer function model structure for control algorithm design and simulation based on control system theory analysis and comprehensive pitch axis characteristics:

This model structure possesses clear physical significance: the integral element (1/s) reflects fundamental position control system characteristics, the first-order element represents primary system dynamic response (time constant approximately 26 ms), and the small time delay element (5 ms) simulates system high-frequency dynamics and sensor delay. While maintaining mathematical simplicity, this model structure accurately characterizes three key system properties: integral characteristics (high gain at low frequencies), first-order inertial characteristics (dynamic response), and small time delay characteristics (high-frequency attenuation), providing a reliable foundation for subsequent control algorithm design.

The transfer function model serves three critical roles in subsequent control algorithm design. First, it provides the simulation environment for PSO global optimization detailed in Sect. 3.3, enabling evaluation of thousands of candidate RBF parameter sets and convergence to near-optimal solutions before deployment by accurately capturing the system’s integral characteristics, first-order dynamics, and time delay. Second, the model’s nonlinear characteristics, particularly the interaction between integral element and time delay, define the required compensation capability of the RBF network, informing the 5-neuron structure design to approximate nonlinear response while maintaining computational efficiency. Third, the model establishes consistent evaluation criteria across all compared control methods including classical PID, RBF-PID, and PSO-RBF-PID, ensuring fair comparison by providing identical system dynamics, nonlinearities, and disturbances. While this model abstracts certain complexities for mathematical tractability, Sect. 2.3 introduces comprehensive nonlinear elements including friction, backlash, and gravitational effects into the simulation framework, ensuring validated controller robustness extends to realistic operating conditions.

System nonlinear characteristics and environmental impact analysis

Throughout this manuscript, \(\:{\text{B}}_{\text{L}}\) consistently denotes the load-side viscous friction coefficient with value \({{\text{B}}_{\text{L}}} = 3.4 \times {10^{ - 4}}{\text{N m s/rad}}\). While Eq. (12) in Sect. 2.2.1 and Eq. (18) below describe the same physical parameter, they appear in different modeling contexts: dynamic modeling and nonlinearity analysis respectively. For consistency, \(\:{\text{B}}_{\text{L}}\) is uniformly adopted throughout the text to represent this parameter.

The spectrometer dual-axis turntable pitch axis control system exhibits multiple nonlinear characteristics and environmental impact factors that collectively constrain system control accuracy and complicate control algorithm design. Understanding and analyzing these characteristics proves crucial for developing high-performance control strategies.

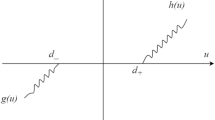

Friction nonlinearity constitutes an important factor affecting precision positioning. System friction torque includes static friction, Coulomb friction, and viscous friction components, with the mathematical mode:

where the parameters are \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{s}}=\text{0.012}\text{N}\cdot \text{m}\) (static friction torque), \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{c}}=\text{0.008}\text{N} \text{m}\) (Coulomb friction coefficient), and \({B_L} = 3.4 \times {10^{ - 4}}{\text{Nms/rad}}\) (viscous friction coefficient) respectively. Friction characteristics discontinuity near zero velocity causes dead-zone phenomena. Specifically: when angular velocity \(\left| \omega \right| < {\omega _{{\text{threshold}}}}\) (threshold approximately 0.001 rad/s), static friction dominates and the system exhibits alternating “stick-slip” behavior; once static friction is overcome during startup, friction force suddenly drops to the Coulomb friction level, inducing position overshoot; during low-speed precision positioning phases (\(|\omega | < 0.01rad/s\)), this nonlinear friction leads to positioning errors up to \(\pm 0.5\text{arc-sec}\), becoming one of the key factors limiting system accuracy. Furthermore, friction characteristics vary with temperature, lubrication state, and operating time, increasing control uncertainty.

Gravitational influence represents a unique nonlinear factor in pitch axis systems. The torque generated by the load grating (0.32 kg) under gravitational action exhibits a nonlinear relationship with angle:

Within large angular ranges, linearization errors approach 5%, significantly affecting system stability. Gravitational torque nonlinear characteristics make fixed-parameter controllers difficult to maintain consistent performance throughout the entire operating range.

Mechanical backlash of approximately 0.02° in the transmission system forms typical dead-zone nonlinearity, resulting in position uncertainty of about 0.001°, directly affecting spectral measurement accuracy. Mathematically, this is represented as a piecewise function:

Parameter uncertainty further complicates control, with significant variations in key system parameters: load inertia varies approximately ± 15% with grating position; friction coefficients fluctuate up to ± 30% due to temperature effects; motor parameters vary approximately ± 8% with temperature changes. Among environmental factors, temperature variations can produce positioning errors of 0.5-1 arc-sec per 1 °C; external vibration disturbances (\(\:{\text{A}}_{\text{d}}\) approximately 0.002–0.005 N·m, \(\:{\text{f}}_{\text{d}}=5-500\text{Hz}\)) and electromagnetic interference (sensor noise approximately 0.05%) also significantly impact system performance.

These nonlinear characteristics present differentiated challenges for various control strategies: traditional PID control has limited adaptability to nonlinearity and parameter variations; RBF neural networks can adapt to system nonlinearity through online learning but face efficiency limitations; while PSO-RBF-PID control through global optimization is expected to improve system adaptability to complex nonlinearity and parameter variations. These characteristics constitute key testing conditions for validating intelligent control algorithm superiority.

Control algorithm design

Classical PID control and theoretical analysis

Classical Proportional-Integral-Derivative controllers are widely applied in precision positioning due to their simplicity and reliability. For the pitch axis system, the continuous-time PID controller is expressed as:

For the established transfer function in Eq. 17, Ziegler-Nichols tuning yields \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{p}}=\text{4.8,}{\text{K}}_{\text{i}}=\text{22.5,}{\text{K}}_{\text{d}}=\text{0.28}\). Practical implementation employs incremental algorithm:

with sampling period \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{s}}=\text{0.001}\text{s}\) and control output \(\:\text{u}\text{(}\text{k})=\text{u}\text{(}\text{k}-\text{1)}+{\Delta }\text{u}\text{(}\text{k}\text{)}\). Incremental implementation offers advantages including anti-integral windup and algorithmic simplicity.

Despite their simple structure, fixed-parameter PID controllers face fundamental limitations for the dual-axis turntable system. These limitations include inadequate adaptation to system nonlinearities such as \(\pm 15\%\) load variation and \(\pm 30\%\) friction changes, phase lag in high-frequency tracking tasks, limited disturbance rejection capability, and difficulty simultaneously achieving fast response and high-precision steady-state performance across different operating points. These limitations motivate the advanced control strategies developed in subsequent sections, with classical PID serving as the baseline for quantifying intelligent control performance improvements.

Adaptive control method based on RBF neural network

Radial Basis Function (RBF) neural networks possess unique advantages in solving nonlinear problems in precision control systems due to their excellent nonlinear mapping capability, fast learning convergence, and structural simplicity. This section designs an adaptive PID control method based on RBF neural networks, addressing traditional PID control limitations when confronting system nonlinearity and parameter uncertainty through online learning and parameter adjustment capabilities.

The RBF neural network adopts a three-layer feedforward structure with basic mathematical expression:

where, \(\:\text{X}\) is the input vector, \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{i}}\) is the center vector of the \(\:\text{i}\)-th hidden neuron, \(\:\phi_{\text{i}}\) is the radial basis function, \(\:{\text{w}}_{\text{ji}}\) is the connection weight from the hidden layer to the output layer, \(\:{\text{b}}_{\text{j}}\) is the output layer threshold, \(\:\text{n}\) is the number of hidden layer neurons, and \(\:\text{m}\) is the number of output layer neurons. The hidden layer neurons adopt a Gaussian function form:

For the spectrometer dual-axis turntable pitch axis control system, a three-input three-output RBF network structure is designed as shown in Fig. 2. The input layer receives system error \(\:\text{e}\left(\text{t}\right)\), error rate \(\:\dot{\text{e}}\left(\text{t}\right)\), and desired angle \(\:{\theta}_{\text{r}}\left(\text{t}\right)\), forming the input vector: \(\:\text{X} = {\left[\text{e}\left(\text{t}\right)\text{,}\dot{\text{e}}\left(\text{t}\right)\text{,}{\theta}_{\text{r}}\left(\text{t}\right)\right]}^{\text{T}}\). Considering the computational efficiency requirements of real-time control, the hidden layer adopts 5 neurons, balancing network performance with computational load. The output layer produces three parameters of the PID controller \(\:\text{Y} = {\left[{\text{K}}_{\text{p}}\text{,}{\text{K}}_{\text{i}}\text{,}{\text{K}}_{\text{d}}\right]}^{\text{T}}\), achieving adaptive control parameter adjustment.

The mathematical expression of the RBF network-based PID controller is:

where, \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{p}}\left(\text{X}\right)\),\(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{i}}\left(\text{X}\right)\), and \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{d}}\left(\text{X}\right)\) are adaptive PID parameters calculated by the RBF network based on the input states. To ensure control system stability, parameter variation ranges are designed as:

where, \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{p}\text{0}}=\text{4.8}\), \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{i}\text{0}}=\text{22.5}\), \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{d}\text{0}}=\text{0.28}\) are the initial PID parameters, \(\:{\Delta }{\text{K}}_{\text{p}}\), \(\:{\Delta }{\text{K}}_{\text{i}}\), \(\:{\Delta }{\text{K}}_{\text{d}}\) are adjustment ranges, and \(\:{\text{f}}_{\text{p}}\left(\text{X}\right)\), \(\:{\text{f}}_{\text{i}}\left(\text{X}\right)\), \(\:{\text{f}}_{\text{d}}\left(\text{X}\right)\) are RBF network outputs with value ranges of [− 1,1].

The RBF network learning process aims to minimize the objective function:

where, \(\:{{\alpha }}_{\text{1}}=\text{0.6}\), \(\:{{\alpha }}_{\text{2}}=\text{0.}\text{15}\), \(\:{{\alpha }}_{\text{3}}=\text{0.}\text{2}\), \(\:{{\alpha }}_{\text{4}}=\text{0.}\text{05}\) are weight coefficients corresponding to system transient error, dynamic characteristics, cumulative error, and control energy consumption, respectively. Weight updating employs improved gradient descent method:

where, \(\beta =0.8\) is the momentum coefficient, \(\:{\eta}_{\text{0}}=\text{0.}\text{05}\) is the initial learning rate, and \(\:\lambda=\text{1.2}\) is the adaptive adjustment parameter. When the error is large, learning rate is small to prevent drastic parameter changes; when error decreases, learning rate increases to accelerate convergence. Center vector updating employs unsupervised K-means clustering algorithm, where \(\:{\eta}_{\text{c}}\) is the center vector learning rate:

Stability analysis of the RBF-PID control system employs the Lyapunov method. The Lyapunov function is constructed as:

where, \(\:{\text{w}}_{\text{ji}}^{{*}}\left(\text{k}\right)\) is the optimal weight. Through analysis of \(\:{\Delta }\text{V}\left(\text{k}\right) = \text{V}\left(\text{k}+\text{1}\right)-\text{V}\left(\text{k}\right)\), the sufficient condition for system stability is that the learning rate satisfies:

where, \(\:{\lambda}_{\text{max}}\left({\Phi}^{\text{T}}\Phi\right)\) is the maximum eigenvalue of the matrix \(\:{\Phi}^{\text{T}}\Phi\), and \(\:\Phi\) is the radial basis function matrix. Through theoretical analysis and numerical verification, when the learning rate is set to \(\:{\eta}_{\text{0}}=\text{0.05}\), the system can guarantee asymptotic stability.

For system parameter uncertainty and external disturbances, the RBF-PID controller exhibits excellent robustness. Assuming the system model contains parameter perturbations and external disturbances:

where \(\:\Delta \text{K}\) and \(\:\Delta \text{p}\) are parameter perturbations, and \(\:\text{d}\left(\text{t}\right)\) is external disturbance. Theoretical analysis shows that when \(\:|\Delta K|<0.45\) and \(\:|\Delta K|<0.38\) are satisfied, the RBF-PID control system maintains stability. Compared to traditional PID control (stability margins of approximately \(\:|\Delta K|<0.25\) and \(\:|\Delta a|<0.22\)), the RBF-PID controller possesses stronger robustness and can accommodate wider ranges of parameter variations and external disturbances.

The RBF-PID controller achieves online adaptive adjustment of PID parameters through neural networks, effectively addressing nonlinear characteristics and parameter uncertainty of the spectrometer dual-axis turntable pitch axis. Compared to traditional PID control, the RBF-PID controller can automatically compensate for friction nonlinearity and gravitational effects, adapt to system parameter variations, enhance system resistance to external disturbances, and maintain consistent control performance under different operating conditions. However, RBF-PID controller performance largely depends on network initial parameters and learning efficiency, being susceptible to local optimal solutions, which motivates exploration of more advanced global optimization algorithms to further improve control performance.

PSO-RBF-PID composite control strategy design

The selection of PSO, RBFNN, and PID components for the dual-axis turntable system is based on systematic consideration of specific requirements and challenges. The baseline PID controller is chosen for its proven industrial reliability, deterministic behavior, and real-time compatibility with 1 kHz control loops required for arc-second precision. RBF neural networks are specifically selected over alternative architectures due to four critical advantages: local approximation property enabling targeted compensation of nonlinearities in specific operating regions, fast convergence with separable parameter structure compared to multi-layer perceptrons, universal approximation capability with compact structure where 5 hidden neurons prove sufficient for modeling system nonlinear characteristics, and interpretability through Gaussian basis functions providing intuitive understanding of compensation mechanisms. PSO is chosen as the global optimizer over alternatives such as genetic algorithms, simulated annealing, and gradient-based methods due to its derivative-free operation essential for optimizing non-differentiable RBF structures, population-based global search effectively escaping local optima, rapid convergence within 50–100 iterations making offline optimization practical, and simple implementation without complex genetic operators. This synergistic integration creates a control architecture where PID provides stable baseline control, RBFNN enables adaptive nonlinearity compensation, and PSO ensures globally-optimized initialization, specifically addressing the dual-axis turntable’s challenges of arc-second precision requirements, nonlinear friction and gravitational effects, and parameter uncertainty.

While the aforementioned RBF-PID controller possesses adaptive capability, its performance largely depends on RBF network initial parameters and learning efficiency, making it prone to local optimal solutions. To overcome this limitation, this section introduces Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm for global optimization of RBF neural network parameters, proposing a PSO-RBF-PID composite control strategy to achieve higher precision pitch axis control.

Particle Swarm Optimization is a global optimization method based on swarm intelligence that finds optimal solutions by simulating bird flocking foraging behavior. In the PSO algorithm, each particle represents a candidate solution in the solution space, with particle movement guided by individual historical optimal positions and group optimal positions, gradually converging toward the global optimal solution. The particle position and velocity update equations are:

where, \(\:{\text{v}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{k}}\) and \(\:{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{k}}\) are the velocity and position vectors of the \(\:\text{i}\)-th particle at the \(\:\text{k}\)-th iteration, respectively; \(\:{\text{p}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{k}}\) is the individual historical optimal position, \(\:{\text{p}}_{\text{g}}^{\text{k}}\) is the group global optimal position, \(\:\text{w}\) is the inertia weight, \(\:{\text{c}}_{\text{1}}\) and \(\:{\text{c}}_{\text{2}}\) are acceleration constants, and \(\:{\text{r}}_{\text{1}}\) and \(\:{\text{r}}_{\text{2}}\) are random numbers in the [0,1] interval. This research adopts a dynamic inertia weight strategy to balance global exploration and local refinement capabilities:

where \({w_{\max }} = 0.9,{w_{\min }} = 0.4,{K_{\max }} = 100\) is the maximum iteration number, and \(\:\text{k}\) is the current iteration. The \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{max}}\) value was determined from 30 independent optimization runs, showing typical convergence within 75–85 iterations to stable values (Fig. 3), with \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{m}\text{ax}}=\text{100}\) providing adequate safety margin.

Three specific enhancements address RBF network parameter optimization characteristics:

(1) Nonlinear inertia weight decay. Implementation uses \(w(k) = {w_{\max }} - ({w_{\max }} - {w_{\min }}){(k/{K_{\max }})^{1.2}}\), achieving approximately 21% faster convergence than linear decay (\(\:{\alpha }=\text{1.0}\)) by enabling extensive exploration of the 35-dimensional parameter space initially and intensive local refinement later.

(2) Adaptive mutation mechanism. Population diversity is monitored via average pairwise distance \(D(k) = (1/{N^2})\sum \sum \|{x_{i(k)}} - {x_{j(k)}}\|\). Mutation \({x_{g(k + 1)}} = {x_{g(k)}} + 0.15 \times N\)(0, 0.2×search_range) triggers when \(D(k) < 0.1 \times D(0)\) or when global best shows no improvement for 10 consecutive iterations. Ablation studies demonstrate this mechanism eliminates the 23% suboptimal convergence rate observed in 30 test runs without mutation.

(3) Hierarchical parameter optimization. The 35-dimensional space (5 centers×3D + 5 widths + 5 × 3 weights) is processed in three stages: iterations 1–30 optimize centers and widths (20D), iterations 31–60 optimize weights (15D), iterations 61–100 jointly refine all parameters with reduced search range (\(\pm 20 \%\)). This reduces average optimization time from 145 to 78 min.

As shown in Fig. 4, the PSO-RBF-PID control system comprises desired angle input, error calculation, PSO-optimized RBF neural network model, PID controller, dual-axis turntable pitch axis system, and performance evaluation modules. The RBF neural network takes error signal e(t), error rate ė(t), and desired angle θr(t) as inputs, outputting adaptive PID parameters Kp, Ki, and Kd to achieve online controller adjustment.

The PSO algorithm primarily optimizes three parameter types: RBF network center vectors \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{i}}\), width parameters \(\:{{\sigma }}_{\text{i}}\), and connection weights \(\:{\text{w}}_{\text{i}}\). Considering the RBF network has 5 hidden layer neurons and 3 outputs, particle dimension is 35. A hierarchical optimization strategy is adopted to reduce search space complexity: first optimizing center vectors and width parameters, then optimizing weights, and finally fine-tuning all parameters. The optimization objective of the PSO-RBF-PID control algorithm is to minimize the comprehensive performance index function:

where, \(\:\text{T}\) is the evaluation time window, and \(\:{{\alpha }}_{\text{1}}=\text{0.5}\), \(\:{{\alpha }}_{\text{2}}=\text{0.}\text{2}\), \(\:{{\alpha }}_{\text{3}}=\text{0.}\text{1}\), \(\:{{\alpha }}_{\text{4}}=\text{0.}\text{2}\) are weight coefficients. This index function comprehensively considers system transient response, dynamic characteristics, control energy consumption, and steady-state accuracy requirements.

As shown in Fig. 5, control algorithm implementation adopts a “offline optimization + online adjustment” dual-stage strategy. In the offline optimization stage, the PSO algorithm iteratively optimizes RBF network parameters through system simulation models, ensuring convergence to near-global optimal solutions; in the online control stage, optimized network parameters are used for real-time control while preserving RBF network adaptive learning capability to achieve dynamic parameter fine-tuning.

The PSO-RBF-PID controller possesses clear advantages compared to traditional methods: obtaining more reasonable network initial parameters through PSO global optimization, avoiding local optima; adopting a composite mechanism of “global optimization + local adaptation” to balance offline optimization and online learning; the optimization process comprehensively considers multiple performance indicators, achieving optimal balance among various indices. Theoretical analysis indicates that this controller can address system nonlinear characteristics, parameter uncertainty, and external disturbances, and is expected to significantly improve spectrometer dual-axis turntable control performance. PSO offline optimization focuses on system global performance, including step response, sinusoidal tracking, and anti-disturbance capability, while RBF network online learning concentrates on adapting to system dynamic characteristic changes. The two complement each other, providing reliable assurance for high-precision control of spectrometer dual-axis turntables.

Simulation implementation and results analysis

Simulation environment and model construction

This research constructs a simulation environment for the spectrometer dual-axis turntable pitch axis control system using the MATLAB/Simulink platform to comparatively analyze performance differences among traditional PID, RBF-PID, and PSO-RBF-PID control algorithms. The simulation system employs a fixed-step solver with 1000 Hz sampling frequency and 0.001 s time step, ensuring capture of rapid system dynamics while meeting real-time control precision requirements.

As shown in Fig. 6, the simulation system adopts modular design consisting of signal source module, controller module, controlled object module, and performance analysis module. The signal source module generates step signals, sinusoidal signals, and complex trajectory signals, covering various typical operating conditions encountered in actual spectrometer operation. The controller module encapsulates the three control algorithms for comparison, ensuring identical operating conditions.

The evaluation index system includes transient performance indicators (rise time \(\:{\text{t}}_{\text{r}}\), overshoot \(\:{\sigma }\%\), settling time \(\:{\text{t}}_{\text{s}}\)), steady-state performance indicators (steady-state error \(\:{\text{e}}_{\text{ss}}\), root mean square error RMSE), and control energy indicator \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{u}}\). The system also incorporates parameter perturbation modules and external disturbance injection functions to test controller robustness.

Simulation testing encompasses three groups of typical operating conditions: step response testing, sinusoidal tracking testing, and complex trajectory tracking testing, plus system parameter variation and external disturbance testing. Through these tests, the superiority of the three control strategies in spectrometer dual-axis turntable pitch axis control is systematically analyzed.

Key control parameters and their selection principles are summarized in Table 1. PSO parameters include population size of 30 balancing search diversity and computational cost for the 35-dimensional optimization space, maximum iterations \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{m}\text{ax}}=\text{100}\) providing safety margin beyond typical 75–85 iteration convergence, inertia weight range with \(\:{\text{w}}_{\text{m}\text{ax}}=\text{0.9}\) and \(\:{\text{w}}_{\text{m}\text{in}}=\text{0.4}\) following linear decay to balance exploration and exploitation phases, acceleration constants \(\:\text{c}_{1}=\text{c}_{2}=2.0\) following standard PSO configuration, and mutation threshold of 10 iterations for diversity injection. RBF network employs 5 hidden neurons sufficient for approximating pitch axis nonlinearities while maintaining sub-millisecond computation, K-means clustering for data-driven center initialization, width range [0.1, 2.0] covering input space while preventing overfitting, weight range [− 3.0, 3.0] bounded to ensure stability margins, and conservative center learning rate \(\:{\eta}_{\text{c}}=\text{0.01}\) preventing online drift from PSO-optimized positions. PID base parameters \({K_{p0}} = 4.8,{K_{i0}} = 22.5,{K_{d0}} = 0.28\) are obtained from Ziegler-Nichols tuning, with adjustment ranges \(\Delta {K_p} = \pm 2.0,\Delta {K_i} = \pm 10.0,\Delta {K_d} = \pm 0.15\) allowing 40–50% parameter variation for nonlinearity compensation. Performance weights are \(\:{\alpha }_{1}=0.5\) for transient error, \(\:{\alpha }_{2}=0.2\) for dynamic characteristic, \(\:{\alpha }_{3}=0.1\) for control energy, and \(\:{\alpha }_{4}=0.2\) for steady-state precision, prioritizing position accuracy. Simulation employs 1000 Hz sampling frequency, 10× faster than system bandwidth of approximately 25 Hz, satisfying Nyquist criterion with margin and ensuring deterministic real-time compatibility.

Control performance comparative analysis

Performance of the three control algorithms is systematically compared through three typical operating conditions: step response, sinusoidal tracking, and complex trajectory tracking, comprehensively evaluating their applicability in precision positioning, dynamic tracking, and complex tasks.

Step response performance comparison

To evaluate fundamental dynamic characteristics of control systems, step tests with amplitudes of 1.0° and 1.1° are designed (sampling frequency 1000 Hz). Figure 7 shows response curves of the three controllers to 1.1° step signals and parameter adaptive adjustment processes.

As shown in Fig. 7a, traditional PID exhibits longer rise time and obvious oscillation; RBF-PID shows improved response speed but maximum overshoot; PSO-RBF-PID achieves optimal balance between response speed and stability, demonstrating fast transient response and good damping characteristics. Figure 7b shows the parameter adaptive adjustment process of the PSO-RBF-PID controller: in early response stages, proportional gain Kp rapidly increases to accelerate system response; when error decreases, integral gain Ki and derivative gain Kd gradually adjust to suppress oscillation; approaching steady state, Ki decreases to reduce overshoot while Kd maintains appropriate levels to provide sufficient damping.

Step response performance analysis (a) Response comparison of three controllers to 1.1° step signal with target angle changing from 0 to 1.1° at t = 2s (b) Parameter adaptive adjustment curves of PSO-RBF-PID controller showing (i) proportional gain \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{p}}\) adjustment, (ii) integral gain \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{i}}\) adjustment, and (iii) derivative gain \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{d}}\) adjustment.

Table 2 quantifies key performance indicators of the three controllers. Regarding rise time, PSO-RBF-PID demonstrates significant performance improvements under both 1.0° and 1.1° step conditions; for overshoot, PSO-RBF-PID maintains relatively consistent overshoot characteristics under both conditions, beneficial for subsequent calibration; concerning settling time, PSO-RBF-PID exhibits faster settling characteristics; for steady-state error, PSO-RBF-PID achieves 0.7-1.0 arc-second accuracy, showing significant improvement compared to traditional PID and RBF-PID controllers, meeting high-precision positioning requirements.

Combining theoretical analysis with experimental data, PSO-RBF-PID controller advantages in step response testing primarily stem from its “global optimization + local adaptation” mechanism. PSO optimization ensures RBF network initial parameters approach globally optimal states, while real-time adaptive mechanisms dynamically adjust control parameters according to system states, effectively compensating for system nonlinear characteristics and parameter uncertainty, achieving excellent balance between fast response and high-precision steady state.

Sinusoidal tracking performance comparison

Spectrometer operation often requires periodic scanning motion, with sinusoidal tracking performance directly affecting spectral measurement accuracy. This section designs two typical operating conditions: high-frequency mode (5 Hz, amplitude 0.2°) simulating fast scanning, and low-frequency mode (0.5 Hz, amplitude 2°) simulating precision scanning, corresponding to high-throughput analysis and high-resolution analysis requirements, respectively.

High-frequency mode tracking results are shown in Fig. 8. From global waveform comparison in Fig. 8a, traditional PID and RBF-PID controllers both exhibit obvious phase lag and amplitude attenuation; although PSO-RBF-PID controller also shows some amplitude attenuation, phase characteristics are significantly improved. Error curve analysis in Fig. 8b indicates that PSO-RBF-PID tracking accuracy is obviously superior to the other two methods. Local magnification regions in Fig. 8c,d clearly present significant differences in phase characteristics among the three controllers: traditional PID phase lag reaches 99.92°, RBF-PID is 73.70°, while PSO-RBF-PID reduces to 26.56°, with phase tracking characteristics significantly improved. This accuracy improvement is crucial for spectrometer wavelength resolution, enabling equipment to identify more subtle spectral changes.

Low-frequency operating condition test results are shown in Fig. 9. Under this condition, all three controllers can track reference signals relatively well, but error curves in Fig. 9b reveal substantial control accuracy differences: PSO-RBF-PID controller’s maximum error is approximately 0.12°, obviously superior to traditional PID; moreover, PSO-RBF-PID error distribution is more uniform with reduced standard deviation, indicating relatively consistent control accuracy throughout the entire scanning range.

The parameter adaptive adjustment mechanism of PSO-RBF-PID controller exhibits differentiated characteristics under different frequency conditions as shown in Fig. 10. Under high-frequency conditions (Fig. 10a), control parameters show large-amplitude periodic adjustments synchronized with input signal frequency; under low-frequency conditions (Fig. 10b), parameter adjustment amplitude is smaller but maintains periodic variations. This adaptive mechanism enables the controller to dynamically optimize control behavior according to signal frequency characteristics: under high-frequency conditions, large parameter adjustments compensate for system phase and amplitude characteristics; under low-frequency conditions, parameter fine-tuning maintains stable tracking accuracy.

Table 3 summarizes key performance indicators of sinusoidal tracking tests. Under high-frequency conditions, PSO-RBF-PID controller’s root mean square error (RMSE) shows significant reduction compared to traditional PID, with maximum tracking error also significantly improved; under low-frequency conditions, all indicators demonstrate excellent optimization effects, with amplitude attenuation characteristics also improved. For spectrometer systems, reduced phase lag and improved amplitude characteristics directly enhance wavelength calibration accuracy and spectral measurement consistency.

Complex trajectory tracking performance comparison

Actual spectral measurement processes typically involve non-periodic complex motions including acceleration-deceleration and fine positioning stages. To simulate this working environment, a composite trajectory signal containing multiple dynamic characteristics is designed with the following specifications. The trajectory covers total travel of 1.5° over 10 s, structured in three phases: acceleration phase from 0 to 3 s with linear velocity ramp from 0 to 0.3°/s, constant velocity phase from 3 to 7 s maintaining baseline velocity of 0.3°/s with superimposed multi-frequency oscillation, and deceleration phase from 7 to 10 s with linear velocity ramp from 0.3°/s to 0.

During the constant velocity phase, the reference signal incorporates three sinusoidal components to simulate realistic environmental disturbances and fine scanning requirements. The mathematical expression is \({\theta _r}ef(t) = {\theta _b}ase(t) + {\Sigma _i}{A_i}\sin (2\pi {f_i}t + {\varphi _i})\) for t ∈ [3, 7]s, where Component 1 has amplitude \(\:\text{A}_{1}=0.025^{\circ}\), frequency \(\:\text{f}_{1}=2 \text{Hz}\), and phase \(\:{\varphi }_{1} =0^{\circ}\) representing low-frequency drift; Component 2 has amplitude \(\:\text{A}_{2}=0.015^{\circ}\), frequency \(\:\text{f}_{2}=5\text{Hz}\), and phase \(\:{\varphi }_{2} =\pi\text{/4}\) representing mid-frequency vibration; Component 3 has amplitude \(\:\text{A}_{3}=0.010^{\circ}\), frequency \(\:\text{f}_{3}=10\text{Hz}\), and phase \(\varphi_{3}=\pi\text{/2}\) representing high-frequency disturbance. The total amplitude envelope reaches 0.05° spanning 2–10 Hz bandwidth. This multi-frequency design specifically challenges the controller’s ability to simultaneously track mixed low-frequency drifts and high-frequency perturbations, maintain stable baseline motion while rejecting oscillatory components, and transition smoothly between acceleration, constant velocity, and deceleration phases without exciting mechanical resonances.

Figure 11 shows complex trajectory tracking performance analysis. From overall trajectory tracking curves in Fig. 11(a), the three controllers exhibit different performance characteristics in complex trajectory tracking tasks. PSO-RBF-PID controller demonstrates superior tracking accuracy for reference signals containing multi-frequency components; RBF-PID controller ranks second; traditional PID controller shows relatively poor performance when tracking high-frequency components, with certain deviations from target trajectories. The constant velocity segment local magnification in Fig. 11(b) further reveals capability differences among the three controllers in handling micro-oscillation signals. PSO-RBF-PID can follow signal changes relatively well, while traditional PID shows obvious phase lag and amplitude distortion. Tracking error comparison (Fig. 11(c)) shows that at points with large trajectory change rates, all controllers produce larger error peaks, but PSO-RBF-PID error amplitude is obviously smaller than the other two schemes. Figure 11(d) demonstrates the parameter adaptive adjustment mechanism of PSO-RBF-PID. At points with large trajectory change rates, all three control parameters show obvious adjustment peaks; during constant velocity micro-oscillation segments, parameters exhibit small periodic adjustments synchronized with input signal frequency characteristics. This real-time parameter adjustment based on system states is the key mechanism for its excellent performance.

Table 4 data indicates that PSO-RBF-PID controller demonstrates superior comprehensive performance in composite trajectory tracking compared to the other two controllers. Its RMSE and IAE both show better control effects; maximum trajectory deviation is also improved. Regarding control energy consumption, PSO-RBF-PID is slightly higher than the other two controllers, reflecting reasonable trade-offs between high-precision control and energy consumption.

Integrating results from three test categories, PSO-RBF-PID controller demonstrates optimal performance under various typical operating conditions, with advantages particularly pronounced when processing high-frequency signals and complex trajectories. Through the strategy combining PSO global optimization with RBF network online learning, the nonlinear and parameter uncertainty problems difficult for traditional control methods to address are successfully resolved, providing effective solutions for high-precision control of spectrometer dual-axis turntables.

Comparative experiments with other control methods

To comprehensively evaluate the PSO-RBF-PID controller, Fuzzy-PID and Sliding Mode Control (SMC) are introduced for comparison beyond the classical PID and RBF-PID. The Fuzzy-PID controller employs seven membership functions (NB, NM, NS, Z, PS, PM, PB) with 49 fuzzy rules for adaptive parameter adjustment. The SMC is designed with sliding surface \(\:\text{s} = {\dot{e}}+\lambda \text{e}\text{(}\lambda=\text{25)}\), control law \(\:\text{u} = {\text{u}}_{\text{e}\text{q}} + {\text{u}}_{\text{s}\text{w}}\), where equivalent control \({\text{u}}_{\text{eq}}=(\lambda K/{\tau }^{2}) e + ((2\zeta /\tau + \lambda)K/{\tau }^{2}){\dot{e}}\), switching control \(\:{\text{u}}_{\text{s}\text{w}}= - \varepsilon \cdot \text{sign}\text{(}\text{s}\text{)(}\varepsilon =\text{0.5)}\), and boundary layer \(\:\text{|}\text{s}\text{|<}{\varphi } \text{(}{\varphi } =\text{0.01)}\) to reduce chattering.

Figure 12 presents the step response comparison for 1.0° step input. The response curves show that PSO-RBF-PID achieves the fastest rise and smallest steady-state deviation, converging rapidly despite some overshoot. SMC exhibits good rapidity and smaller overshoot but shows slight oscillation in steady state. Fuzzy-PID has smooth response but longer rise time. RBF-PID shows obvious overshoot. Classical PID presents the longest rise time and oscillatory decay.

Table 5 quantifies key performance indicators. PSO-RBF-PID achieves 30.3ms rise time, representing 41.4% improvement over classical PID (51.7ms), demonstrating the fastest dynamic response. Most critically, PSO-RBF-PID achieves 0.7 arc-sec steady-state error, significantly outperforming SMC (1.4 arc-sec), RBF-PID (1.8 arc-sec), Fuzzy-PID (2.1 arc-sec), and classical PID (3.6 arc-sec), with over 50% improvement compared to the second-best method. Notably, while Fuzzy-PID improves classical PID through rule-based design, discrete rule precision limitations restrict its arc-second level control capability. Although SMC demonstrates good robustness, the inherent switching mechanism causes control signal chattering (peak-to-peak approximately 0.3 V), potentially exciting mechanical resonances.

Figure 13 presents sinusoidal tracking performance in high-frequency mode (5 Hz, 0.2° amplitude). Global waveform comparison (Fig. 13(a)) shows classical PID exhibits severe phase lag and amplitude attenuation, while PSO-RBF-PID tracking curve fits the reference signal most closely. Tracking error comparison (Fig. 13(b)) demonstrates PSO-RBF-PID has the smallest error oscillation amplitude. Local magnification analysis (Figs. 13(c)(d)) further reveals phase tracking characteristic differences: classical PID suffers severe phase lag, while PSO-RBF-PID tracking waveform nearly coincides with the reference signal.

Quantitative indicators show PSO-RBF-PID achieves 26.6° phase lag and 227.7 arc-sec RMSE, representing 59.2% and 53.1% improvements respectively compared to Fuzzy-PID (65.3°, 485.2 arc-sec), and 48.9% and 33.3% improvements respectively compared to SMC (52.1°, 341.8 arc-sec). This advantage stems from its unique design: PSO performs global search in 35-dimensional parameter space, avoiding Fuzzy-PID rule design subjectivity; RBF network’s Gaussian basis functions provide smooth continuous compensation, avoiding SMC switching mechanism chattering; the dual-stage strategy of offline global optimization and online adaptive learning achieves optimal balance between global performance and local flexibility. Comparative experiments validate PSO-RBF-PID’s significant advantages in steady-state accuracy and high-frequency dynamic tracking, providing an effective control solution for spectrometers and other ultra-precision systems.

Anti-disturbance performance and robustness testing

In engineering application environments, control systems inevitably face challenges from parameter uncertainty and external disturbances. This section evaluates robustness performance of the three control algorithms through system parameter variation adaptability testing and external disturbance suppression capability testing, providing theoretical basis for spectrometer dual-axis turntable applications in actual environments.

System parameter variation adaptability test

During long-term spectrometer operation, system parameters undergo changes due to temperature drift, component aging, and load variations. Control algorithm adaptability to parameter changes directly affects instrument long-term stability and reliability. This section designs two parameter perturbation test types: system gain variation (± 30%) and load inertia variation (± 20%), with parameters suddenly changed during stable system operation (at t = 1s and t = 3s) to evaluate control algorithm adaptability.

Figure 14 shows step response characteristics under system gain parameter variation conditions. In the gain increase of 30% test (Fig. 14a), all three controllers exhibit different degrees of overshoot, with PSO-RBF-PID controller showing relatively small overshoot amplitude and faster recovery speed. Under gain decrease of 30% conditions (Fig. 14b), PSO-RBF-PID demonstrates smaller undershoot amplitude and shorter recovery time, reflecting good gain robustness.

Inertia parameter variation test results (Fig. 15) further verify excellent PSO-RBF-PID controller performance. When inertia increases by 20% (Fig. 15a), PSO-RBF-PID controller maintains small overshoot amplitude and smooth adjustment process; when inertia decreases by 20% (Fig. 15b), system dynamic characteristics accelerate, but PSO-RBF-PID can still avoid high-frequency oscillations in RBF-PID and excessive response problems in traditional PID, maintaining system stability.

Table 6 quantifies key performance indicators of the three controllers under parameter variation conditions. PSO-RBF-PID controller demonstrates superior adaptability performance under all parameter variation conditions, with integral absolute error (IAE) showing improvement compared to other controllers, and disturbance recovery time also exhibiting excellent characteristics. Particularly under the more stringent condition of 30% gain decrease, PSO-RBF-PID performance advantages are more obvious, reflecting effective reduction of control system sensitivity to parameter changes.

Excellent parameter adaptability performance of PSO-RBF-PID controller stems from its dual optimization mechanism: reasonable network structure obtained through PSO global optimization provides favorable initial characteristics for the controller, while RBF network online learning capability enables the controller to adjust PID parameters according to actual system dynamic characteristics, achieving adaptive compensation. This “global optimization + local adaptation” composite mechanism effectively reduces controller sensitivity to parameter changes, enhancing system adaptability, which is significant for spectrometer long-term stable operation under complex environments with temperature fluctuations and load variations.

External disturbance rejection capability test

Spectrometers in actual working environments are frequently affected by external factors including mechanical vibrations, electromagnetic interference, and temperature fluctuations. This section designs two typical test scenarios comprising step disturbance and continuous sinusoidal disturbance to evaluate control algorithm anti-disturbance capability.

The continuous sinusoidal disturbance parameters consisting of 4 Hz frequency and 0.075° amplitude are selected based on three considerations aligned with realistic spectrometer operating conditions. Regarding frequency selection, 4 Hz is chosen to approximate the system natural frequency of approximately 4 Hz calculated from damping ratio \(\:\zeta =\text{0.939}\) and time constant \(\:{\tau }=\text{0.0538}\text{s}\), representing the most challenging condition for disturbance rejection as it risks resonance excitation; to match typical environmental vibration frequencies in laboratory settings including building structural modes ranging from 2 to 6 Hz and HVAC systems ranging from 3 to 5 Hz; and to test controller bandwidth adequacy where 4 Hz approaches the Nyquist limit for the system’s bandwidth of approximately 25 Hz. Regarding amplitude selection, 0.075° equivalent to 270 arc-sec represents 7.5% of the 1° nominal positioning command simulating realistic environmental disturbance magnitude relative to target signals; represents approximately 100 to 300 times the arc-second precision target creating significant challenge without overwhelming the control system; and is comparable to measured vibration amplitudes in precision optical instruments with typical range from 50 to 400 arc-sec. The combined 4 Hz and 0.075° condition specifically tests the controller’s capability to reject near-resonance disturbances of substantial magnitude while maintaining arc-second precision, which is critical for spectrometer applications where environmental vibrations must not degrade spectral resolution.

Step disturbance simulates sudden impacts to the system. After the system stably tracks 1° target value, a step disturbance with amplitude 0.1° equivalent to 10% of the input signal is applied at t = 2s. Sinusoidal disturbance simulates environmental vibration by applying continuous sinusoidal perturbation with frequency 4 Hz and amplitude 0.075° equivalent to 7.5% of the input signal.

Figure 16a shows system response characteristics under step disturbance. After disturbance application, all three controllers produce different degrees of deviation, with PSO-RBF-PID controller showing relatively small deviation amplitude. Error curves in Fig. 16b show that PSO-RBF-PID controller has excellent recovery characteristics with relatively short recovery time. More noteworthy is that after system restabilization, PSO-RBF-PID controller achieves excellent steady-state characteristics, while traditional PID controller exhibits certain residual deviation.

System performance under continuous sinusoidal disturbance shown in Fig. 17 focuses on evaluating controller disturbance rejection capability. The disturbance rejection ratio quantifies controller attenuation capability for external disturbances. For sinusoidal disturbance with frequency \(\:\omega _{\text{d}}\) and amplitude \(\:{\text{A}}_{\text{d}}\) applied to the system, the steady-state output oscillation amplitude \(\:{\text{A}}_{\text{o}\text{ut}}\) is measured, with the rejection ratio in decibels calculated as \(\:\text{DR}\text{(}\text{dB})=20\text{log}_{10}\text{(}{\text{A}}_{\text{o}}\text{ut}/{\text{A}}_{\text{d}}\text{)}\). For the PSO-RBF-PID controller under 4 Hz sinusoidal disturbance conditions: the input disturbance amplitude is \(\:{\text{A}}_{\text{d}}=0.075^{\circ}=270\text{arc-sec}\), the steady-state output oscillation amplitude measured from the error signal in Fig. 17(b) after transient decay at t > 3 s is \(\:{\text{A}}_{\text{o}\text{ut}}=\text{46.8}\text{arc-sec}\), yielding rejection ratio \(\:\text{DR}=\text{20}\text{log}_{10}\text{(46.8/270)=20}\text{log}_{10}\text{(0.173)=-25.31}\text{dB}\). This indicates the controller attenuates the 4 Hz disturbance by a factor of 5.77× which equals approximately 10^(25.31/20).

As shown in Fig. 17(a), the PSO-RBF-PID controller demonstrates good attenuation effect for 4 Hz disturbance signals with disturbance rejection ratio reaching − 25.31 dB, showing significant improvement compared to classical PID at -19.55 dB. Comparative values for other controllers include: Classical PID achieves output oscillation amplitude \(\:{\text{A}}_{\text{o}\text{ut}}=\text{113.2}\) arc-sec with rejection ratio \(\:\text{DR}=-\text{19.55}\text{dB}\) corresponding to 3.38× attenuation; RBF-PID achieves \(\:{\text{A}}_{\text{o}\text{ut}}=\text{73.6}\text{arc-sec}\) with \(\:\text{DR}=-\text{22.57}\text{dB}\) corresponding to 4.77× attenuation. Error curve analysis in Fig. 17b shows that PSO-RBF-PID controller error presents regular sinusoidal waveform with relatively small maximum amplitude, improved compared to both classical PID and RBF-PID. Regarding steady-state effects, the PSO-RBF-PID controller demonstrates superior disturbance rejection capability. This superior disturbance rejection stems from optimized RBF basis functions providing accurate disturbance pattern recognition and adaptive PID parameters generating appropriate compensatory control actions synchronized with disturbance frequency.

Table 7 summarizes key performance indicators of the three control algorithms in anti-disturbance testing. PSO-RBF-PID controller demonstrates superior performance in most evaluation indicators compared to the other two schemes, whether in recovery capability from sudden disturbances or suppression effects on continuous disturbances.

Excellent anti-disturbance performance of PSO-RBF-PID controller stems from its unique dynamic compensation mechanism. PSO global optimization enables RBF networks to more accurately capture system nonlinear characteristics and disturbance patterns; real-time adaptive adjustment can promptly respond to system changes caused by disturbances, suppressing disturbance effects through dynamic PID parameter adjustment. Particularly when processing continuous periodic disturbances, PSO-RBF-PID controller demonstrates characteristics similar to internal model control, capable of learning disturbance spectrum features and providing targeted compensation.

Integrating system parameter variation adaptability and external disturbance suppression capability test results, PSO-RBF-PID controller demonstrates clear advantages in addressing system uncertainty and external disturbances, providing effective solutions for spectrometer dual-axis turntables to maintain high-precision operation in complex working environments. Compared to traditional PID controllers that are easily affected by disturbances and basic RBF-PID controllers limited by initial parameter selection, PSO-RBF-PID controller achieves superior control robustness and accuracy through its “global optimization + local adaptation” mechanism, meeting spectrometer system requirements for precision positioning and stable operation.

Conclusion

This work presents a PSO-RBF-PID composite control strategy for precision angular control of spectrometer dual-axis turntables. The research demonstrates that this method can improve pitch axis positioning accuracy to 0.7-1.0 arc-second levels, satisfying the technical requirements of broadband high-resolution spectral measurements.

By integrating the global optimization capability of particle swarm optimization algorithms with the online learning characteristics of RBF neural networks, the designed controller effectively addresses system nonlinear characteristics and parameter uncertainty problems. Simulation results confirm that when system parameters undergo ± 30% variations, the controller maintains excellent positioning accuracy and rapid recovery characteristics. Additionally, this controller achieves disturbance suppression capability of -25.31 dB, significantly outperforming traditional PID control methods.

The primary contribution of this research lies in establishing a “offline global optimization + online adaptive adjustment” dual-stage control architecture, overcoming the limitation of pure RBF-PID controllers being prone to local optima. This design approach provides reference value for other electromechanical systems requiring high-precision positioning.

Research limitations are primarily manifested in two aspects: first, the simulation model does not fully consider the influence of environmental factors such as temperature variations; second, the real-time performance of the control algorithm requires validation on actual hardware platforms. Future work will focus on conducting physical verification experiments and exploring algorithm optimization strategies to meet the real-time requirements of engineering applications. Simultaneously, consideration will be given to extending this control method to coordinated control of other axes to further improve the comprehensive performance of the entire dual-axis turntable system.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yang, Q. Broadband high-resolution line-imaging spectrometer with a large working distance range. Opt. Commun. 583, 131802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2025.131802 (2025).

Hao, J. et al. Detection of low concentrations of the l-valine solution using high-resolution THz-ATR spectroscopy. Opt. Commun. 583, 131779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2025.131779 (2025).

Catalucci, S. et al. Optical metrology for digital manufacturing: a review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 120, 4271–4290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-022-09084-5 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Controlling the wavefront aberration of a large-aperture and high-precision holographic diffraction grating. Light Sci. Appl. 14, 112. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-01785-2 (2025).

He, X. et al. Optimization of production process parameters for Polishing machine tools in crankshaft abrasive belt based on BP neural network and NSGA-II. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 134, 3971–3983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-024-14250-y (2024).

Guojun, Y. et al. Separation detection and correction of mosaic errors in mosaic gratings based on two detection lights with the same diffraction order and different incident angles. Opt. Lasers Eng. 128, 106281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlaseng.2020.106281 (2020).

Park, H. C. et al. A nonlinear backstepping controller design for high-precision tracking applications with input-delay gimbal systems. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 9, 530. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9050530 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Wavelength calibration of a solar spectral irradiance radiometer and validation by correlation photon coincidence counting. Sol Energy. 264, 112035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2023.112035 (2023).

Chen, L. & Xu, Q. Fuzzy-Based Adaptive Reliable Motion Control of a Piezoelectric Nanopositioning System. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 32(8), 4413–4425. https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2024.3399115 (2024).

Sheng, K. & Wang, Z. Y. Spontaneous spin and Valley polarizations in novel RuO₂(MgF)₂ and RuO2(ZnF)₂ ferrovalley semiconductors with ultrahigh curie temperatures. Acta Mater. 291, 120988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2025.120988 (2025).

Park, S. C. & Kim, H. Semiconducting transport properties of graphene doped by metal oxide. Solid State Commun. 402, 115964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssc.2025.115964 (2025).

Xu, B. et al. High-accuracy target tracking for multistatic passive radar based on a deep feedforward neural network. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 24, 1214–1230. https://doi.org/10.1631/FITEE.2200260 (2023).

García Peña, D. et al. Exploring deep fully convolutional neural networks for surface defect detection in complex geometries. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 134, 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-024-14069-7 (2024).

Furui, Z. et al. Analysis and correction of geometrical error-induced pointing errors of a space laser communication APT system. Int. J. Optomechatronics. 15, 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15599612.2021.1895923 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. A review: High-Precision angle measurement technologies. Sensors 24, 1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24061755 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Interpretability of deep convolutional neural networks on rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Meas. Sci. Technol. 33, 055005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6501/ac41a5 (2022).

Shi, X., Zhao, H. & Fan, Z. Parameter optimization of nonlinear PID controller using RBF neural network for continuous stirred tank reactor. Meas. Control. 56, 1835–1843. https://doi.org/10.1177/00202940231189307 (2023).

Mohindru, P. Review on PID, fuzzy and hybrid fuzzy PID controllers for controlling non-linear dynamic behaviour of chemical plants. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57, 97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-024-10743-0 (2024).

Kim, S. J., Suh, J. H. & Model-Free, R. B. F. Neural network Intelligent-PID control applying adaptive robust term for quadrotor system. Drones 8, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8050179 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. PSO-NMPC control strategy based path tracking control of mining LHD (scraper). Sci. Rep. 14, 28516. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79248-8 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Recent progress, challenges and future prospects of applied deep reinforcement learning: A practical perspective in path planning. Neurocomputing 608, 128423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128423 (2024).

Ren, L. et al. A novel chaotic particle swarm optimized backpropagation neural network PID controller for Four-Switch Buck–Boost converters. Actuators 13, 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/act13110464 (2024).

Nayak, J. et al. 25 years of particle swarm optimization: flourishing voyage of two decades. Arch. Comput. Meth Eng. 30, 1663–1725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-022-09849-x (2023).

Kashyap, A. K. & Parhi, D. R. Particle swarm optimization aided PID gait controller design for a humanoid robot. ISA Trans. 114, 306–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2020.12.033 (2021).

Zhu, F. et al. Dung beetle optimization algorithm based on quantum computing and multi-strategy fusion for solving engineering problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 236, 121219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121219 (2024).

Acknowledgements