Abstract

Movements of fishes among habitats often correspond to shifting resource availability and can occur in response to fluctuating freshwater inflows in coastal systems. Seasonal availability of prey can provide resources that increase fitness, yet hydrologic variability can influence the movements of both consumers and prey. Shifts in the timing/magnitude of prey availability driven by climate and water management may lead to a resource mismatch, carrying consequences for growth, survival, and reproduction. Here, we examined how seasonal/interannual variation in prey biomass (sunfishes, Lepomis spp.) affects the body condition of Common Snook (Centropomus undecimalis) in Everglades National Park. Further, we investigated how condition relates to hydrologic variation (water level, temperature, and the duration of marsh drydown). Using GLMMs, we modeled snook condition in relation to sunfish biomass, hydrologic conditions, and fish size. Our results indicate that snook body condition was best explained by a combination of factors, increasing with higher sunfish biomass, lower water levels, during the transition between wet/dry seasons, and with fish size. Population health is not typically included as a management endpoint in monitoring efforts, although quantifying condition is straightforward and cost effective. We highlight that incorporating bioindicators for multiple species into monitoring and assessment could aid in evaluating the efficacy of water management and restoration efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Animal populations depend on the availability of high-quality food resources to provide the energy and nutrients required for growth, survival, and reproduction. Often, consumers ranging from small birds, to freshwater fishes, to large marine mammals depend on resources that vary in both space and time1,2,3,4. Spatiotemporally discrete food resources can disproportionately contribute to the growth and condition of individuals, provide surplus energy that maximizes reproductive success, and increase the survival of offspring5,6,7,8. Consumers move among habitats to take advantage of these resources, and these movements often represent adaptive behaviors that match the timing of favorable habitat conditions and resource availability4,7,9,10. Climate change, anthropogenic habitat alterations, and differential species responses to these changes may alter the timing and magnitude of resource availability in the future, and the ability to track these temporal shifts may lead to matches or mismatches among consumers and critical resources, carrying implications for long-term population trends11,12,13,14,15,16.

For riverine fishes, the magnitude, frequency, duration, timing, and rate of change of freshwater flows can influence the availability/abundance of prey resources, and thus the movements of consumers into profitable foraging areas17,18. In seasonally fluctuating systems, connectivity between river channels and floodplains serves as a vector for the transport of nutrients, organic matter, and organisms that enhance productivity and can provide consumers with access to prey subsidies19,20,21. Past research has illustrated how fish species in diverse regions benefit from floodplain-derived subsidies, including for Northern Pike (Esox lucius) and Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens) in the temperate St. Lawrence River, Canada22,23, cichlids (Cichla spp.) in Venezuela’s tropical Cinaruco River24, and Barramundi (Lates calcarifer) and catfishes (Neoarius spp.) in multiple rivers of Australia25,26,27. Body condition has been linked to floodplain subsidies, and is a useful metric for assessing the fitness of fishes, and which has been linked to health, immune responses, survival, and reproduction23,28,29. While past research has described how environmental conditions affect body condition29,30,31, relatively few studies have explicitly linked variation in the availability and magnitude of floodplain prey subsidies to the body condition of riverine fish, partly due to a lack of high spatial/temporal resolution and long-term community datasets that track this variation2.

Common Snook (Centropomus undecimalis, hereafter snook) are a widely distributed tropical euryhaline fish species that are well-suited for investigating how spatiotemporally patchy prey subsidies affect fish body condition. Snook are found in rivers, estuaries, and coastal waters of the western Atlantic, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico, with their range extending from Brazil to Cedar Key on Florida’s east coast and Cape Canaveral on Florida’s west coast30,32,33. Snook are marine-obligate spawners requiring high salinities for successful reproduction34,35,36, and form spawning aggregations in the lower estuaries, marine inlets, and coastal waters during the wet season when increasing freshwater flows can trigger migrations37,38,39,40,41. Post spawning, snook can move back into coastal rivers that provide both refuge from lethal water temperatures ( < ~ 10 °C) in the winter months33,42, and enhanced foraging opportunities on freshwater prey30,43,44,45,46. Snook are protandrous hermaphrodites, and their transition from male to female has been reported to occur outside of the spawning season47,48. Energy acquisition outside of the spawning season can be important for not only sex transitioning, but also for the maturation and the development of oocytes, and spawning migrations in the following year48.

Past research has linked energy flow from floodplain habitats surrounding coastal rivers to the diet of snook inhabiting the riverine habitats49. In Florida rivers where snook occur, freshwater prey subsidies are concentrated into river channels as water levels recede in adjacent floodplain marshes during the dry season (November to April), and serve as a key resource for snook in the months before/after spawning30,43,44,45,46. A study of snook in the Peace River indicated that body condition was positively correlated with longer floodplain inundation, with condition increasing as water levels dropped seasonally, and stomach contents from gastric lavage consisting of large numbers of floodplain species (e.g., crayfishes, Procambarus spp.; Brown Hoplo, Hoplosternum littorale; sunfishes, Lepomis spp.), illustrating the importance of floodplain prey concentration30. However, the magnitude and species identity of these prey subsidies can vary widely from year-to-year based on hydrologic conditions (e.g., length of floodplain inundation, salinity, and temperature)50,51. Thus, there remains a need for research that quantifies how seasonal and interannual variation in the availability of freshwater prey and associated hydrological conditions that drive both prey production and concentration affect consumer body condition.

In this study, we use a long-term electrofishing dataset (2004–2021) of fish communities in the Shark River, Everglades National Park (ENP), to examine how the magnitude of a freshwater prey subsidy (sunfishes, Lepomis spp.) and hydrologic conditions affect variation in the body condition of snook. Our primary research questions were: how is snook body condition affected by the timing and magnitude of the sunfish prey subsidy, and does seasonal and annual variation in hydrologic conditions (namely marsh water level, temperature, and the duration of floodplain inundation) which drives freshwater prey availability also correlate with snook body condition? We hypothesized that: (1) Seasonal increases in the sunfish prey subsidy will result in higher body condition, (2) Falling water levels will result in higher snook condition, due to prey concentration in the river channels, and (3) Snook condition is highest when marshes water levels first drop below a minimum depth threshold that results in prey movement/concentration, before this seasonal resource becomes depleted due to the foraging activity of mobile predators. To test our hypotheses, we modeled snook body condition in relation to sunfish biomass calculated from long-term sampling data and our focal hydrologic variables.

Methods

Study site

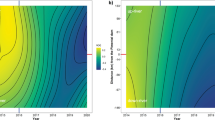

The Shark River is a low-gradient coastal river system in the southwestern region of Everglades National Park, with river channels that extend approximately 32 km inland from the coast and a drainage area of roughly 1700 km2 (Fig. 1). The hydrologic regime is shaped by the regional subtropical climate, and seasonal peaks in precipitation, with more than 75% of the system’s rainfall occurring during the wet season in May-October52,53,54. The magnitude and timing of freshwater flow is influenced by atmospheric teleconnections at both long and short timescales (El Niño Southern Oscillation, Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation), which results in a high degree of interannual variability in seasonal water levels including droughts and prolonged flooding (Fig. 2)54,55,56. Throughout the twentieth century, drastic alterations to the region’s hydrology resulting from intensive water management for urban and agricultural development have reduced freshwater flows by more than half57,58.

Map of the study area in Everglades National Park where fish community sampling was conducted between 2004 and 2021. Panel (a) shows the location of the Shark River in SW Florida, and panel (b) depicts the 15 electrofishing sites (three transects/site) where fish were captured. Blue dots denote the five upper river sites sampled at higher frequency and used to model how sunfish biomass and hydrologic variation affect snook Kn, and red dots indicate additional sites/transects throughout the river where fish length/weights were used to calculate the mean population average body condition (Kn, calculated for all sites, blue and red dots). Black diamonds show the location of hydrologic monitoring stations where environmental conditions (water level, temperature, salinity) were measured. Figure created using QGIS version 3.28.9 (https://qgis.org/).

Hydrographs of water level in the freshwater marsh of the upper Shark River at station MO215 (see Fig. 1b) for each year of the study (2004–2021). Individual color-coded lines correspond to each sampling year and illustrate the high degree of interannual variability in both the timing and magnitude of freshwater flows. The solid black line represents the long-term mean daily water level for the full period that MO215 has been recording data (1996-present) with the shaded area indicating standard error in water level across the dataset. The horizontal hashed line denotes the 30 cm threshold that corresponds to the beginning of marsh prey concentration in the river channels during falling water levels.

The Shark River consists of distinct habitat zones, with freshwater creeks and marshes in the upper river that transition into mangrove forests, with progressively larger and more saline channels that flow into the Gulf of Mexico39,43,59,60,61. The oligohaline upper river (Fig. 1b) consists of narrow shallow channels bordered by a combination of mangroves and freshwater marshes containing a mix of sawgrass (Cladium spp.) and freshwater woody plant species, with limited tidal influence in the wet season44,62,63,64. Upper river water levels are closely tied to precipitation and conditions in the adjacent marshes, and as water levels drop throughout the dry season (November – April), floodplain species move from the drying marshes into the river channels seeking refuge43,44,45,46. Midriver, a mesohaline central embayment (Tarpon Bay) is marked by a transition from a predominantly freshwater fish community to one primarily consisting of estuarine and marine species, with shallow open habitats and more pronounced tidal fluctuations44,46,61.

Fish sampling

Fish sampling in the Shark River took place between November 2004 and June 2021 as part of the Florida Coastal Everglades Long Term Ecological Research Program65,66. Sampling was conducted throughout the year, with three primary sampling events each year. The first sampling event was performed following the end of the wet season when marsh water levels were near their annual peak (November-December). A second sampling event was conducted during the early dry season as water levels recede (January-March). A third sampling event occurred when water levels neared their minimum in the late dry season (April-May). Sampling consisted of boat-based electrofishing at 15 fixed sites in the upper and middle river44,46. Each site consists of three replicate transects, for a total of 45 transects shocked per seasonal sampling event (Fig. 1b). In many years of study (2010–2014, 2016–2021), additional sampling events were conducted in-between the three primary sampling events at five upper river sites, such that in essence these sites were sampled monthly (15 transects-shown in blue in Fig. 1b). This increase in sampling frequency allowed us to better track the timing and size of the seasonal pulse of freshwater prey entering ecotonal creeks from drying marshes. Further, additional sampling also provided a higher degree of temporal resolution to assess how snook abundance and prey landscapes change seasonally, as marsh water levels recede, and freshwater prey become concentrated in the river channels. Thus, sampling at these upper river sites occurred between two and eight times per sampling year over the course of the study (mean = 5 headwater sampling events/year, n = 73 total sampling events at upper river sites).

Following standardized methods, fish were captured using a boat-mounted GPP 9.0 electrofisher (Smith Root, Vancouver, WA, USA)44,46. At each site/transect, electrofishing was performed while the boat was motored at idle speed along a randomly selected shoreline using a pulsed 2:1 on/off power ratio for a total of 300 s of shock time to standardize sampling effort. Two netters were stationed on the bow of the boat, and once immobilized, fish were netted and immediately transferred to an on-board aerated livewell. Approximately 100 m of shoreline was sampled for each transect, with the total distance sampled (meters) measured by a boat-mounted GPS unit and recorded at the end of each transect in order to accurately calculate sunfish and snook abundance and sunfish biomass per 100 m of shoreline for use in statistical models. For all samples, captured sunfish and snook were identified to the species level, measured (standard length in cm, SL), weighed (grams), and released live after being allowed to recuperate in ambient water. All field protocols and handling procedures for animal subjects in this study were ethically reviewed and approved by Florida International University’s Animal Care and Use Program under protocol numbers IACUC-20-057-CR01 and IACUC-21-003-CR01, and conform to ARRIVE guidelines for reporting studies related to animal research (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Statistical analyses

Snook condition

To examine how seasonal/interannual variation in the magnitude of the freshwater prey subsidy and hydrologic conditions affect snook body condition, we calculated a relative condition factor for the Shark River snook population based on all individuals captured during long-term sampling where length and weight data were available. Relative condition (Kn) was selected as our condition metric, which uses a length-weight regression relationship specific to the study population67. These methods are consistent with previous studies examining the body condition of fishes24,28,29,30,31,68. For each snook where length and weight were measured, relative condition was calculated as W/W’, where W is the measured weight of the fish, and W’ is the estimated mean weight for fish of that length across the entire study population. To estimate the mean weight-at-length relationship for the population, we first log10-transformed fish length (L = standard length in cm) and weight (W = weight in grams), and used a linear regression relationship to produce a value representing the average year-round body condition of all Shark River snook captured throughout the upper and middle river: log10(W) = α + β(log10L), where β is the slope and α is the intercept. To reduce the influence of outliers and instances where field measurement error was suspected, we removed records that were greater/less than two standard deviations of the weight-at-length regression residuals when calculating the mean weight-at-length relationship (detailed in Klassen et al. 2014)69. W’ was then calculated using regression coefficients, where W’ = αLβ, and a relative condition factor value of Kn was calculated for each fish in the dataset (Kn = W/W’). Finally, we selected Kn estimates for use in our statistical models for fish that were captured at the five uppermost river sites (Fig. 1b). These sites were selected because they received the most frequent sampling effort over the long-term dataset, and they are in close proximity to the freshwater marshes and thus experience a higher contribution from freshwater prey subsidies44,46.

Sunfish biomass

To quantify the magnitude of the marsh prey subsidy available to snook where and when they were captured, biomass was calculated from long-term sampling data for sunfishes (Lepomis spp.) at each transect/sampling event for the five upper river sites (Fig. 1b). We chose sunfishes to represent the seasonal marsh prey subsidy not only because the abundance of these prey species in the river channels has been shown to fluctuate in response to seasonal marsh water levels in the Shark River, but also because a reported 80% of prey items found in snook stomach contents during the transition between the wet and dry season consisted of sunfish species43,44,46,51. Exploratory analyses also investigated whether a lagged relationship to prey biomass better explained snook condition. However, when a model which included prey biomass when snook were captured was compared to a model using and prey biomass at the previous sampling event, lagged biomass produced both a higher AICc and that was not statistically significant. Thus, sunfish biomass was selected as our final variable.

Sunfish biomass was standardized across each transect, site and seasonal sampling event, and calculated as the weight (wet weight, grams) per 100 m of shoreline (summed weight of all sunfish captured in a transect / total distance sampled in meters x 100). In some cases, weight was only recorded for a subset of sunfishes captured, and for these we followed Klassen et al.69 and estimated species-specific wet biomass using the equation W = aLb, consistent with our weight calculations for snook Kn (described above). Length-weight relationships were derived from linear regression models built for each sunfish species that included all recorded field measurements collected over the course of our study (2004–2021), where W = wet weight biomass in grams, a = the intercept, and b = the SL coefficient (slope) from the regression models. Sunfish biomass was first calculated for each transect, site, and sampling event, and the mean sunfish biomass for each sampling event/site (averaging the biomass among the 3 transects at each site) was then calculated to represent the prey subsidy available to snook on the date and at the sample site where they were captured. Because snook are mobile predators that can take advantage of prey resources beyond their precise capture location (i.e., the ~ 100 m electrofishing transect), using the mean sunfish biomass for the three transects at each site allowed us to capture spatial differences among sample sites while also accounting for fine-scale differences in prey availability.

Statistical models of snook condition

We used Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) with a Gaussian error distribution and sample site as a random effect to investigate how the magnitude of the sunfish prey subsidy and seasonal/interannual environmental variation affect snook body condition. The response variable for our models was the estimated relative body condition (Kn, described above) for each snook captured, weighed, and measured at the five upper Shark River sites over the course of our study. Analyses were performed using R statistical software version 4.2.2 and the glmmTMB package70,71.

Modeling consisted of a four-step process where we first examined all independent variables for collinearity. Second, if collinearity was found, we selected the best fitting variable based on the lowest Akaike’s information criterion (AICc)72 by comparing univariate models for each term. Third, we combined all selected variables into a global model. Finally, we reduced the global model using backward selection using the step() function from the stats package in R. For all models, we calculated R-squared values with the Performance package in R73, in order to obtain the amount of variance explained, and selected a final best fitting model based on the lowest AICc score74,75,76,77. We also inspected model residuals to verify that all modeling assumptions were met and evaluate variance inflation factors (VIF) to ensure that results were not influenced by multi-collinearity using the DHARMa and Performance packages in R73,78.

To test hypothesis 1, that seasonal increases in the sunfish prey subsidy available to snook in the river channels result in higher Kn, we used mean sunfish biomass corresponding to the date and site where each individual snook with a calculated Kn was captured. Exploratory models examined whether sunfish abundance (# of sunfish captured per 100 m) may better predict Kn relative to biomass. However, a comparison of univariate models indicated better performance with biomass (AICc > 2 points lower). Additionally, we considered a lagged variable representing sunfish biomass for the site where each snook was captured during the previous sampling event for that year. However, this variable for lagged biomass was not statistically significant (p = 0.37, R squared < 0.01). Thus, mean site biomass at the time of sampling and without a lag was selected in the final models described here.

To test hypothesis 2, that lower water levels result in higher snook Kn, due to prey concentration in the river channels, we used a variable for daily mean water level relative to the North American Vertical Datum of 1988 (NAVD88) obtained from the Everglades Depth Estimation Network (EDEN, https://sofia.usgs.gov/eden/). Water level data were queried for a monitoring station located in the freshwater marsh just upstream from our sample sites (Fig. 1b, station MO215), and we then subtracted the ground surface elevation to determine the water depth at that station (average ground elevation at MO215 = -9.75 cm). Further, to test hypothesis 3, that Kn is highest when marshes water levels first drop below a minimum depth threshold that results in prey movement/concentration, and before this seasonal resource becomes depleted due to the foraging activity of mobile predators, we calculated a metric for the number of days in the previous 180 days (6 months) that marsh water level dropped below 30 cm, a level that corresponds to marsh flood stage. The ground elevation difference between sawgrass ridges and lower wet-prairie marsh sloughs in the Everglades ranges between approximately 10 and 25 cm (Trexler et al. 2005), and a water level > 30 cm should indicate inundation of most, if not all, habitat in the marshes adjacent to the river channels. Wet season water levels above 30 cm have also been reported to correspond to increases in sunfish biomass in the river channels in the following dry season50,51. The six-month period prior to the body condition measurement was selected for two reasons. First, the dry season in South Florida extends from November to April52. While marsh drying generally occurs in the later part of this period, hydrologic conditions vary from year to year based on variation in the amount of annual precipitation, the occurrence of hurricanes and tropical storms, and water management (Fig. 2). A window of six months allows us to capture marsh flooding and dry down, with varying numbers of days below 30 cm and varying concentrations of prey across the long-term dataset. As the number of days below 30 cm over the past 6 months increases (hereafter drydown threshold), the abundance of freshwater prey first increases with immigration from marshes and then decreases due to predation as the dry season progresses51. Second, the prior 6-month window also indicates the extent of marsh flooding in the previous wet season, a time-period particularly important for freshwater marsh production, and which can affect the overall abundance of freshwater prey each year79,80,81. High values for days < 30 cm in the prior six months indicate overall lower water levels in the previous wet season, an earlier annual drydown, and a longer dry season duration. To evaluate the efficacy of this 30 cm threshold, or whether prey concentration/flood duration may be better represented by other water levels, we also calculated the number of days < 20 cm marsh water level, and number of days < 10 cm water level over the prior six months. When univariate models were compared using AICc, the 30 cm drydown threshold consistently resulted in better model performance (lowest AICc) and was therefore selected for final models.

In addition to our hypothesized drivers, we included water temperature in our model based on observation that temperature influences body condition in other fish species, and affects marsh prey community structure in the Everglades29,51,82. Daily mean temperature data were obtained from the United States Geological Survey time-series for Bottle Creek (Station 022908295) located just upstream of our sample sites via the South Florida Water Management District’s environmental database (DBHYDRO, https://www.sfwmd.gov/science-data/dbhydro). We also included fish size (SL) as a model variable, because larger fish may be better able to capitalize on large-bodied prey species24,68, and larger migratory snook moving into headwater habitats to exploit the freshwater prey subsidy may benefit from increased prey availability relative to the greater population. Further, we included a factor variable for the sampling year to provide further evidence for the role of interannual variability in snook condition and capture additional model variance not captured by our other modeled variables.

Results

Fish sampling

Between November 2004 and June 2021, 2,994 individual snook were captured during standardized electrofishing across all sites in the Shark River. Snook ranged in size from 2.8 to 79.5 cm SL (mean 38.8 +/- 13.7 cm SD), and in weight from 5.6 to 7,880.0 g (mean 854.4 +/- 940.6 g). Snook weights were not recorded in three of the early sampling years (November 2006 – May 2009), and 487 fish that were missing length or weight data were therefore excluded from Kn estimates and statistical models. The 2,507 fish with data on both length and weight were captured at 73 unique sampling events (Supplementary Table 1). When these fish were included in linear regression models to generate mean weight-at-length relationship for the population, 111 individuals (less than 5%) had greater or less than two times the standard deviation of the residuals suggesting field measurement errors and were excluded from further estimates of Kn. In total, 2,396 individuals served as the basis for mean weight-at-length relationship used to calculate Kn. Of these fish, 1,492 snook (62%) were captured at the five upper river sites adjacent to freshwater marshes (Fig. 1b) between 2004 and 2021, and these fish served as the basis for our statistical models.

Snook condition

The log10 transformed linear regression equation we derived to estimate the mean weight-at-length relationship and estimate Kn for snook in the Shark River, log10(W) = -1.90 + 3.00(log10L), was highly significant (p < 0.01, R-squared = 0.99). When calculated for all Shark River fish, Kn varied both annually (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1) and seasonally (Supplementary Table 2), ranging from 0.70 to 1.29 (mean 1.00 +/- 0.09). Kn was similar when considering separately the 1,492 individuals captured in the upper river sites, where Kn ranged from 0.74 to 1.28 (mean 1.00 +/- 0.09), with a high degree of variation among seasons (Fig. 4). Between the wet and early dry season, the median body condition increased by 7.5% and then decreased by 1.3% as the dry season progressed from early dry to late dry. The highest annual Kn observed across individuals occurred in the 2010/2011 sampling season (mean 1.05 +/- 0.10), peaking in March/April (mean 1.06 +/- 0.07), and the lowest annual mean was observed in both 2015/2016 and 2020/2021 (mean = 0.93 +/- 0.08) with the lowest Kn observed in February of both sampling years (means of 0.91 and 0.89 respectively).

Plot depicting the relative body condition (Kn) of Common Snook for all individuals captured over the course of the study (2004–2021) where length and weight data were available. Blue dots depict fish from 5 the upper river sites most frequently sampled over time and adjacent to freshwater marshes which were used in statistical models predicting how sunfish biomass and water level affect Kn. Red dots show fish captured lower in the river and in Tarpon Bay which were included in the calculations of the average Kn for the entire Shark River snook population. Solid lines show local regression fitting (loess) curves depicting trends over time for both the modeled upper river fish (blue), and all additional individuals captured over the course of the study (red). Note: snook weights were not recorded during sampling events which occurred between November 2006 and May 2009, and Kn was not calculated for these sampling events.

Violin plots depicting the seasonal variation in the relative body condition of Common Snook (Kn) captured at the five uppermost sites in the Shark River adjacent to the freshwater marshes. Wet season sampling (WET) was conducted in November/December following annual water levels maximums, EARLYDRY samples are collected as water levels recede during the dry season (January – March), and LATEDRY sampling occurred at the end of the dry season (April/May) when water levels approach the seasonal minimum.

Sunfish biomass

In total, 5,674 individual sunfish representing six species (Bluegill, Lepomis macrochirus, Redear Sunfish, Lepomis microlophus, Spotted Sunfish, Lepomis punctatus, Dollar Sunfish, Lepomis marginatus, Warmouth, Lepomis gulosus, and Bluespotted Sunfish, Enneacanthus gloriosus) were captured during the 17 years of electrofishing at the upper river sites, and served as the basis for our biomass calculations. Sunfish biomass was highly variable over time, ranging from a mean of zero sunfish captured (occurring at six different sampling events) to 987.83 +/- 392.63 g/100 m in April 2013 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The highest mean annual biomass was recorded in the 2014/2015 sampling season (mean = 515.51 +/- 385.52 g/100 m). The lowest mean biomass was recorded during the 2015/2016 sampling season with a mean catch across all sites/sample dates of 70.68 +/- 63.21 g/100 m, also corresponding to one of two years where mean Kn was lowest.

Factors affecting snook condition

We modeled snook Kn in relation to variables both representing the magnitude of the sunfish prey subsidy and variation in environmental conditions (Table 1). Three candidate metrics for a marsh drydown threshold representing the timing of freshwater prey concentration and extent of wet season flooding (days marsh water level < 10, 20, 30 cm) were highly collinear (Pearson’s correlation > 0.9), and as described above in the methods, we selected days < 30 cm based on the lowest AICc, highest R2 value, and because only the days < 30 cm metric was statistically significant (Supplementary Table 3). High collinearity (Pearson’s correlation > 0.6) was not detected for any other variable pairings, and six variables were included in the global model: Marsh water level, number of days marsh water level < 30 cm over the previous 6 months, water temperature, sunfish biomass, snook size (SL), and sampling year. The global model was reduced using backward selection, and only temperature was removed. Thus, our final model (Table 2) consisted of five variables (Marsh water level, days marsh water level < 30 cm, sunfish biomass, fish size, and sampling year). The combined fixed effects of this model (marginal R2) captured 22% of the variance in snook Kn (Table 1).

To provide insight into how each variable considered may influence the model, and the relative fit of each fixed effect when considered independently, we also examined univariate relationships between the variables and Kn (Table 1), and plotted the isolated effects of each variable in our final model (Fig. 5). All model variables were statistically significant (p < 0.01). Sampling year had the strongest relationship with Kn (marginal R2 = 0.12), followed by water level (marginal R2 = 0.06), sunfish biomass (marginal R2 = 0.04), fish size (marginal R2 = 0.04), and the number of days the marsh level was < 30 cm (marginal R2 = 0.01). Kn showed a positive relationship with both sunfish biomass and fish size, and a negative relationship with water level and the number of days marsh water levels were below 30 cm (Fig. 5).

Plotted variables for the best-fitting GLMM for the relative body condition (Kn) of Common Snook in the Shark River bounded by a 95% confidence interval. Individual effects of each variable kept in the best model in Table 1 are assessed by holding the other variables at a fixed mean value. Together, these variables explain 22% of the long-term variability in Kn between 2004 and 2021. Note: snook weights were not recorded during sampling events which occurred between November 2006 and May 2009, and Kn was not calculated for these sampling events.

Discussion

In this study, we examined how the magnitude of a freshwater prey subsidy, and the seasonal/interannual variation in water level that drives the timing and size of the prey subsidy, affect the body condition of the ecologically important and popular recreational fish species, Common Snook32,83. Our findings illustrate how snook body condition is affected by a combination of these factors, increasing with higher sunfish biomass, lower water levels, during the transition between wet/dry seasons, and with fish size. The quantity and quality of food resources, and favorable environmental conditions that promote trophic linkages, are critical to the long-term performance of animal populations. This can be particularly important when resources fluctuate in space and time, and seasonal/interannual variation that affects resource availability can carry consequences for the growth, survival, and the reproductive success of individuals and populations7,23,84,85,86,87,88.

Many riverine fishes exploit seasonal prey subsidies maintained by fluctuations in the natural flow regime that provide connectivity between river channels and floodplain productivity18,22,24,25,89,90. Anthropogenic alterations to the landscape, climate change, and management of a limited freshwater supply for multiple uses can impact the magnitude and timing of floodplain resources17,91. Our results show significant relationships between sunfish biomass, water level, fish size, and interannual variation, with fixed effects from our final model accounting for 22% of the variance in snook body condition across 14 sampling years.

Our models indicate a positive correlation between sunfish biomass and snook condition. These results provide additional evidence to past research describing the seasonal importance of marsh sunfishes to snook foraging43,44,46. Boucek and Rehage44 conducted gastric lavage sampling in the Shark River, and found that snook preferentially feed on sunfishes, constituting 80% of prey items present in stomach contents during early marsh drydown. Additionally, Rezek et al.49 used stable isotope analysis coupled with acoustic telemetry, and reported a 69% dietary contribution from freshwater prey for snook, whose distributions are primarily in the upper river. Similar dependencies on specific prey species have been reported for fish in other systems. In Venezuela, 45% of the diet of the piscivorous Cichla temensis (Speckled Pavon) consisted of Semaprochilodus kneri during falling water levels, corresponding to an increase in body condition24,92. Farley et al.23 reported positive correlations between floodplain prey and the body condition of multiple fish species in a large fluvial lake in Quebec, Canada, and that condition was related to flooding duration and magnitude (i.e., the cumulative annual area of the floodplain that was inundated with water). Further, Barramundi in Australia that migrated into freshwater rivers and thus accessed floodplain prey subsides grew 25% faster in the year following migration than non-migratory individuals who remained in the estuary85.

Increases in the annual sunfish prey subsidy during the dry season may be particularly important for snook, because the dry season precedes annual reproductive migrations that begin with the onset of the wet season38,39,40,41, and at a time where body condition may be inherently lower because of energetic expenditures during the prior spawning season. Previous histological studies of female snook have shown how the dry season corresponds to the development and regeneration of oocytes, and high hepato-somatic indices indicate that this time-period is also where sex transition and maturation occurs48. Energy acquired during the dry season can therefore be allocated to sexual maturation, sex transition, downstream spawning migrations, and ultimately reproduction39,48. In five of the seven years (71%) where annual mean Kn was > 1.0, peak sunfish biomass occurred in March and April, just prior to the beginning of the spawning season and corresponding to the dry season period, and when past acoustic telemetry studies in the Shark River have reported the greatest upper river habitat use by tagged fish (up to 70% of acoustic detections recorded in upper river)45.

Our results showed an effect of decreasing marsh water levels on snook condition, illustrating the importance of prey concentration during the dry season. Falling water levels typically correspond to the highest fish density in floodplain river food webs, and an increase in predator-prey interactions93,94. For example, the feeding activity of multiple cichlid species (Cichla temensis, Cichla intermedia) in the Cinaruco River, Venezuela, were highest during falling water levels, also corresponding to the highest mean body condition95,96. Further, an investigation of piscivorous fishes in Upper Paraná River, Brazil, found a negative relationship between prolonged flooding and body condition31. Correlations between fluctuating water level and body condition have also been reported for snook. In a study in the Peace River, Blewett et al.30 used eight years of sampling data to show how snook consumed high numbers of prey originating from river floodplains, and that there was a 1.2-fold increase in body condition as water levels receded at onset of the dry season. The importance of seasonal prey concentration has also been described for other consumers in the Everglades. Nesting and foraging success of Everglades wading birds has been linked to seasonal water level fluctuations in the freshwater marshes, particularly falling water levels which concentrate prey and increase accessibility for consumers97,98.

Our models also indicate a relationship between the number of days that marsh water levels dropped below 30 cm in the six months prior to capture and snook body condition. Kn progressively dropped below the mean with increasing time from this 30 cm water level threshold, which corresponds to the beginning of prey concentration in the Shark River51. Other studies have reported similar findings where body condition is highest during the early stages of drydown. In the St. Lawrence River, Canada, the contribution of floodplain prey to the diets of juvenile fish in Lake Saint-Pierre was highest early in the growing season and when floodplain production was highest22.

Fish size was positively related to snook condition, suggesting that larger snook in the upper Shark River may be better able to capitalize on the marsh prey subsidy. Larger migratory snook move into headwater habitats from marine/estuarine habitats in the dry season to exploit freshwater prey subsidies30,43,45, and we hypothesize that larger migrants may gain additional benefit from consuming larger-bodied prey above the gape-limitations of smaller resident fish. Higher condition in larger fish has also been reported for other fish species. For example, the condition of large Barramundi which feed on inundated floodplains in Australian rivers were higher relative to smaller fish, which was attributed to gape limitation and the ability to consume a wider range of prey sizes68. The condition of large-gaped Barramundi remained higher in the months when floodplains were no longer accessible, suggesting that individuals able to capitalize on floodplain prey can offset weight loss during times of lower prey availability with energy gained from a seasonal subsidy68. Similarly, the condition of large Cichla temensis (> 30 cm) which feed on migratory prey during falling water levels was significantly higher than smaller individuals of the same species, which was partially attributed to gape-limitation and the ability to consume large prey species, specifically Semaprochilodus kneri24. Further, Cargnelli et al.99 found that the condition of Bluegill in a Canadian lake was higher in larger fish following the winter months, indicating that resources acquired months earlier can help sustain fish through harsher conditions. Future research able to make comparisons between movement patterns, energy needs as a function of size, and body condition among smaller resident and larger migratory snook would offer valuable additional insight.

Our results demonstrate that interannual variability has a large impact on snook body condition. Year to year variability in condition has been observed in other fishes. For example, in a 14-year study of 16 fish species in Chesapeake Bay, Latour et al.82 found substantial variation in condition among years, and suggested that variation might be explained by interannual differences in primary productivity. In South Florida, the timing and magnitude of seasonal precipitation varies dramatically from year to year52,55, and periodic droughts or prolonged flooding can have a large effect on water levels, marsh inundation, and marsh prey production, all of which can in turn affect snook condition. For example, water levels were exceptionally high throughout the sampling seasons where annual snook condition was the lowest across our dataset (2015/2016 and 2020/2021, mean Kn = 0.93 both years). In these years, dry season marsh water levels did not drop below 30 cm at all in the 2015/2016 dry season, and did not reach this level until mid-May in 2020/2021, reducing the prey concentration effect throughout much of the dry season. Further, 2015/2016 corresponded to the lowest annual sunfish biomass observed in our study (70.7 g/100m, 75% lower than the 14-year average), and in 2020/2021, peak biomass was not reached until May when water level dropped below 30 cm in the marsh. Conversely, the sampling year with the highest snook condition (2010/2011, mean Kn = 1.05) followed a wet season in 2009 where water levels were above the long-term average, and incidentally, following a cold spell in January 2010 which resulted in 80% declines in snook CPUE43,100,101, which may have reduced competition for prey due to decreases in the relative abundance of snook. Blewett et al.30 reported similar findings for snook in the Peace River, with the highest body condition in years with average or above annual water levels, which would result in higher prey production.

Conclusion

We examined how the body condition of snook is correlated with the magnitude of a freshwater prey subsidy (sunfishes, Lepomis spp.) that originates in the freshwater marshes and is concentrated in river channels during falling water levels in the dry season. Further, we investigated how seasonal and interannual environmental variation, which can influence both floodplain productivity and the accessibility to these prey resources, are related to snook body condition. Using statistical models, we illustrate how a combination of these factors results in both seasonal and interannual variation in body condition. Our results suggest not only that the body condition increases with the magnitude of the sunfish prey subsidy, but also that condition increases during falling water levels and is of most benefit to individuals present near floodplain habitats when prey first becomes available and can fully capitalize on this resource. Body condition can have implications for both individuals and populations and may be an informative management metric that provides additional insight on population health and habitat quality not reflected by relative abundance alone. Population health is not typically included as a management end point, although quantifying condition is straightforward and cost effective, can be calculated from existing sampling data. Incorporating bioindicators for multiple species into monitoring and assessment could aid in evaluating the efficacy of water management/restoration efforts. Findings from the present study provide additional insight into the importance of a key prey resource for a valued fishery, and the environmental conditions that maintain access to this resource. This information can be useful when considering freshwater management decisions in a highly managed landscape. Research that describes how resource availability fluctuates over time as a factor of environmental variation, and how this affects the health of consumer populations, can help inform management decisions aimed at the conservation of ecologically, economically, and socially important species.

Data availability

The long-term fish community datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available through the Florida Coastal Everglades Long Term Ecological Research Program under the Environmental Data Initiative66.

References

Cotton, P. A. Seasonal resource tracking by Amazonian hummingbirds. Ibis 149, 135–142 (2007).

Cooke, S. J. et al. A moving target—incorporating knowledge of the Spatial ecology of fish into the assessment and management of freshwater fish populations. Environ. Monit. Assess. 188, 1–18 (2016).

Abrahms, B. et al. Memory and resource tracking drive blue Whale migrations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 5582–5587 (2019).

Abrahms, B. et al. Emerging perspectives on resource tracking and animal movement ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 36, 308–320 (2021).

Drent, R. Balancing the energy budgets of arctic-breeding geese throughout the annual cycle: a progress report. Verh Orn Ges Bayern. 23, 239–264 (1978).

Merkle, J. A. et al. Large herbivores surf waves of green-up during spring. Proc. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 283, 20160456 (2016).

Middleton, A. D. et al. Green-wave surfing increases fat gain in a migratory ungulate. Oikos 127, 1060–1068 (2018).

Van der Graaf, A., Stahl, J., Klimkowska, A., Bakker, J. P. & Drent, R. H. Surfing on a green wave-how plant growth drives spring migration in the barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis. Ardea-Wageningen- 94, 567 (2006).

Avgar, T., Street, G. & Fryxell, J. M. On the adaptive benefits of mammal migration. Can. J. Zool. 92, 481–490 (2014).

Lytle, D. A. & Poff, N. L. Adaptation to natural flow regimes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 94–100 (2004).

Deacy, W. W. et al. Phenological tracking associated with increased salmon consumption by brown bears. Sci. Rep. 8, 11008 (2018).

Post, E. & Forchhammer, M. C. Climate change reduces reproductive success of an Arctic herbivore through trophic mismatch. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 363, 2367–2373 (2007).

Santos, R. O. et al. Cause and consequences of Common Snook (Centropomus undecimalis) space use specialization in a subtropical riverscape. Sci. Rep. 15, 2004 (2025).

Schindler, D. E. et al. Riding the Crimson tide: mobile terrestrial consumers track phenological variation in spawning of an anadromous fish. Biol. Lett. 9, 20130048 (2013).

Sergeant, C. J., Armstrong, J. B. & Ward, E. J. Predator-prey migration phenologies remain synchronised in a warming catchment. Freshw. Biol. 60, 724–732 (2015).

Thackeray, S. J. et al. Phenological sensitivity to climate across taxa and trophic levels. Nature 535, 241 (2016).

Palmer, M. & Ruhi, A. Linkages between flow regime, biota, and ecosystem processes: Implications for river restoration. Science 365, eaaw2087. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw2087 (2019).

Poff, N. et al. The natural flow regime: A paradigm for river conservation and restoration. Bioscience 47, 769–784 (1997).

Garcia, A. et al. Hydrologic pulsing promotes Spatial connectivity and food web subsidies in a subtropical coastal ecosystem. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 567, 17–28 (2017).

Junk, W. J., Bayley, P. B. & Sparks, R. E. in Proceedings of the International Large River Symposium (ed Dodge, D. P.) 110–127 (Can. Spec. Publ. Fish. Aquat. Sci).

Winemiller, K. O. & Jepsen, D. B. Effects of seasonality and fish movement on tropical river food webs. J. Fish Biol. 53, 267–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.1998.tb01032.x (1998).

Farly, L., Hudon, C., Cattaneo, A. & Cabana, G. Seasonality of a floodplain subsidy to the fish community of a large temperate river. Ecosystems 22, 1823–1837 (2019).

Farly, L., Hudon, C., Cattaneo, A. & Cabana, G. Hydrological control of a floodplain subsidy to Littoral riverine fish. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 78, 1782–1792 (2021).

Hoeinghaus, D., Winemiller, K., Layman, C., Arrington, D. & Jepsen, D. Effects of seasonality and migratory prey on body condition of cichla species in a tropical floodplain river. Ecol. Freshw. Fish. 15, 398–407 (2006).

Crook, D. A. et al. Tracking the resource pulse: movement responses of fish to dynamic floodplain habitat in a tropical river. J. Anim. Ecol. 89, 795–807 (2020).

Jardine, T. D. et al. Consumer–resource coupling in wet–dry tropical rivers. J. Anim. Ecol. 81, 310–322 (2012).

Jardine, T. D. et al. Fish mediate high food web connectivity in the lower reaches of a tropical floodplain river. Oecologia 168, 829–838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-011-2148-0 (2012).

Abujanra, F., Agostinho, A. & Hahn, N. Effects of the flood regime on the body condition of fish of different trophic guilds in the upper Paraná river floodplain, Brazil. Brazilian J. Biology. 69, 469–479 (2009).

Brosset, P. et al. Influence of environmental variability and age on the body condition of small pelagic fish in the Gulf of lions. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 529, 219–231 (2015).

Blewett, D. A., Stevens, P. W. & Carter, J. Ecological effects of river flooding on abundance and body condition of a large, Euryhaline fish. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 563, 211–218. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps11960 (2025).

Luz-Agostinho, K. D., Agostinho, A. A., Gomes, L. C. & Fugi, R. Effects of flooding regime on the feeding activity and body condition of piscivorous fish in the upper Paraná river floodplain. Brazilian J. Biology. 69, 481–490 (2009).

Munyandorero, J., Trotter, A., Stevens, P. & Muller, R. The 2020 Stock Assessment of Common Snook, Centropomus Undecimalis (Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, 2020).

Hall-Scharf, B. J. et al. How body size and salinity affects thermal tolerance of a range-expanding fish. Mar. Coastal. Fisheries. 17, vtaf023. https://doi.org/10.1093/mcfafs/vtaf023 (2025).

Ager, L., Hammond, D. & Ware, F. Artificial spawning of Snook. Proc. Annual Conf. Southeast. Association Fish. Wildl. Agencies. 30, 158–166 (1978).

Chapman, P., Horel, G., Fish, W., Jones, K. & Spicola, J. Artificial culture of snook, Rookery Bay, 1977, Job Number 2: induced spawning and fry culture. Annual Report on Sportfish Introductions (Florida Games and Fresh Water Fish Commission, 1978).

Tucker, J. W. Jr Snook and Tarpon Snook culture and preliminary evaluation for commercial farming. Progressive Fish-culturist. 49, 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8640(1987)49%3C49:SATSCA%3E2.0.CO;2 (1987).

Boucek, R., Leone, E., Walters-Burnsed, S., Bickford, J. & Lowerre-Barbieri, S. More than just a spawning location: examining fine scale space use of two estuarine fish species at a spawning aggregation site. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 355 (2017).

Lowerre-Barbieri, S. et al. Spawning site selection and contingent behavior in common snook, centropomus undecimalis. PloS One. 9, e101809. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101809 (2014).

Massie, J. A. et al. Primed and cued: long-term acoustic telemetry links interannual and seasonal variations in freshwater flows to the spawning migrations of Common Snook in the Florida everglades. Mov. Ecol. 10, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-022-00350-5 (2022).

Young, J. M., Yeiser, B. G. & Whittington, J. A. Spatiotemporal dynamics of spawning aggregations of Common Snook on the East Coast of Florida. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 505, 227–240. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps10774 (2014).

Young, J. M., Yeiser, B. G., Ault, E. R., Whittington, J. A. & Dutka-Gianelli, J. Spawning site Fidelity, Catchment, and dispersal of Common Snook along the East Coast of Florida. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 145, 400–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/00028487.2015.1131741 (2016).

Howells, R. G., Sonski, A. J., Shafland, P. L. & Hilton, B. D. Lower temperature tolerance of snook, centropomus undecimalis. Gulf Mexico Sci. 11, 8 (1990).

Boucek, R. E., Heithaus, M. R., Santos, R., Stevens, P. & Rehage, J. S. Can animal habitat use patterns influence their vulnerability to extreme climate events? An estuarine sportfish case study. Glob. Change Biol. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13761 (2017).

Boucek, R. E. & Rehage, J. S. No free lunch: displaced marsh consumers regulate a prey subsidy to an estuarine consumer. Oikos 122, 1453–1464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2013.20994.x (2013).

Rehage, J. S. et al. Untangling Flow-Ecology relationships: effects of seasonal stage variation on Common Snook aggregation and movement rates in the everglades. Estuaries Coasts. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-022-01065-x (2022).

Rehage, J. S. & Loftus, W. F. Seasonal fish community variation in headwater Mangrove creeks in the Southwestern everglades: an examination of their role as dry-down refuges. Bull. Mar. Sci. 80, 625–645 (2007).

Taylor, R. G., Whittington, J. A., Grier, H. J. & Crabtree, R. E. Age, growth, maturation, and protandric sex reversal in common snook, centropomus undecimalis, from the East and West Coasts of South Florida. Fish. Bull. 98, 612–612 (2000).

Young, J. M., Yeiser, B. G., Whittington, J. A. & Dutka-Gianelli, J. Maturation of female Common Snook centropomus undecimalis: implications for managing protandrous fishes. J. Fish Biol. 97, 1317–1331. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.14475 (2020).

Rezek, R. J. et al. Individual consumer movement mediates food web coupling across a coastal ecosystem. Ecosphere 11, e03305. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3305 (2020).

Boucek, R. E., Soula, M., Tamayo, F. & Rehage, J. S. A once in 10 year drought alters the magnitude and quality of a floodplain prey subsidy to coastal river fishes. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 73, 1672–1678. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfas-2015-0507 (2016).

Rezek, R. J. et al. The effects of temperature and flooding duration on the structure and magnitude of a floodplain prey subsidy. Freshw. Biol. 68, 1518–1529 (2023).

Abiy, A. Z., Melesse, A. M., Abtew, W. & Whitman, D. Rainfall trend and variability in Southeast florida: implications for freshwater availability in the everglades. PloS One. 14 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212008 (2019).

Price, R. M., Swart, P. K. & Willoughby, H. E. Seasonal and Spatial variation in the stable isotopic composition (δ 18 O and δD) of precipitation in South Florida. J. Hydrol. 358, 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2008.06.003 (2008).

Saha, A. K. et al. A hydrological budget (2002–2008) for a large subtropical wetland ecosystem indicates marine groundwater discharge accompanies diminished freshwater flow. Estuaries Coasts. 35, 459–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-011-9454-y (2012).

Abiy, A. Z., Melesse, A. M. & Abtew, W. Teleconnection of regional drought to ENSO, PDO, and AMO: Southern Florida and the everglades. Atmosphere 10, 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10060295 (2019).

McIvor, C., Ley, J. & Bjork, R. (Lucie, Delray Beach, 1994).

Marshall, F. E., Wingard, G. L. & Pitts, P. A. Estimates of natural salinity and hydrology in a subtropical estuarine ecosystem: implications for greater everglades restoration. Estuaries Coasts. 37, 1449–1466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-014-9783-8 (2014).

Marshall, F. E., Bernhardt, C. E. & Wingard, G. L. Estimating late 19th century hydrology in the greater everglades ecosystem: an integration of paleoecologic data and models. Front. Environ. Sci. 8 https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2020.00003 (2020).

Matich, P. et al. Ecological niche partitioning within a large predator guild in a nutrient-limited estuary. Limnol. Oceanogr. 62, 934–953. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10477 (2017).

Fry, B. & Smith, T. J. Stable isotope studies of red mangroves and filter feeders from the shark river estuary, Florida. Bull. Mar. Sci. 70, 871–890 (2002).

Rosenblatt, A. E. & Heithaus, M. R. Does variation in movement tactics and trophic interactions among American alligators create habitat linkages? J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 786–798. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01830.x (2011).

Boucek, R. E. & Rehage, J. S. Climate extremes drive changes in functional community structure. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 1821–1831. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12574 (2014).

Chen, R. & Twilley, R. R. Patterns of Mangrove forest structure and soil nutrient dynamics along the shark river Estuary, Florida. Estuaries Coasts. 22, 955–970. https://doi.org/10.2307/1353075 (1999).

Childers, D. L. et al. Relating precipitation and water management to nutrient concentrations in the oligotrophic upside-down estuaries of the Florida everglades. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 602–616. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2006.51.1_part_2.0602 (2006).

Childers, D. L., Gaiser, E. & Ogden, L. A. The Coastal Everglades: the Dynamics of social-ecological Transformation in the South Florida Landscape (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Rehage, J. et al. Seasonal Electrofishing Data from Rookery Branch and Tarpon Bay, Everglades National Park (FCE LTER), November 2004 - ongoing (2025). https://doi.org/10.6073/pasta/f1265ccc240aae0955de83cf1ccd09b3

Anderson, R. O. in Fisheries techniques, 2nd edition 447–482(American Fisheries Society, 1996).

Luiz, O. J. et al. Does a bigger mouth make you fatter? Linking intraspecific gape variability to body condition of a tropical predatory fish. Oecologia 191, 579–585 (2019).

Klassen, J., Gawlik, D. & Botson, B. Length–weight and length–length relationships for common fish and crayfish species in the Everglades, Florida, USA. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 30, 564–566 (2014).

Magnusson, A. et al. glmmTMB: generalized linear mixed models using template model builder. R package version 0.1 3 (2017).

R. A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

Akaike, H. In Selected Papers of Hirotugu Akaike 199–213 (Springer, 1998).

Lüdecke, D., Ben-Shachar, M. S., Patil, I., Waggoner, P. & Makowski, D. Performance: an R package for assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. J. Open. Source Softw. 6 (2021).

Anderson, D. R. Model Based Inference in the Life Sciences: a Primer on Evidence (Springer Science & Business Media, 2007).

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: a Practical information-theoretic Approach (Springer Science & Business Media, 2003).

Johnson, J. B. & Omland, K. S. Model selection in ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2003.10.013 (2004).

Symonds, M. R. & Moussalli, A. A brief guide to model selection, multimodel inference and model averaging in behavioural ecology using akaike’s information criterion. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 65, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-010-1037-6 (2011).

DHARMa Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level / Mixed) Regression Models v. R package version 0.4.5 (2022).

Chick, J. H., Ruetz, C. R. & Trexler, J. C. Spatial scale and abundance patterns of large fish communities in freshwater marshes of the Florida everglades. Wetlands 24, 652–664 (2004).

Trexler, J. C. & Goss, C. W. Aquatic fauna as indicators for everglades restoration: applying dynamic targets in assessments. Ecol. Ind. 9, S108–S119 (2009).

Trexler, J. C. et al. Ecological scale and its implications for freshwater fishes in the Florida everglades. The Everglades, Florida Bay, and Coral Reefs of the Florida Keys: an Ecosystem Sourcebook. CRC, Boca Raton, FL, 153–181 (2002).

Latour, R. J., Gartland, J. & Bonzek, C. F. Spatiotemporal trends and drivers of fish condition in Chesapeake Bay. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 579, 1–17 (2017).

Fedler, T. The economic impact of recreational fishing in the everglades region 1–17 (2009).

Isaac, V. J., Castello, L., Santos, P. R. B. & Ruffino, M. L. Seasonal and interannual dynamics of river-floodplain multispecies fisheries in relation to flood pulses in the lower Amazon. Fish. Res. 183, 352–359 (2016).

Roberts, B. H. et al. Migration to freshwater increases growth rates in a facultatively catadromous tropical fish. Oecologia 191, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-019-04460-7 (2019).

Brandt, L. A., Beauchamp, J. S., Jeffery, B. M., Cherkiss, M. S. & Mazzotti, F. J. Fluctuating water depths affect American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) body condition in the Everglades, Florida, USA. Ecol. Ind. 67, 441–450 (2016).

Briggs-Gonzalez, V. S., Basille, M., Cherkiss, M. S. & Mazzotti, F. J. American crocodiles (Crocodylus acutus) as restoration bioindicators in the Florida everglades. Plos One 16, e0250510 (2021).

Strickland, B. A., Gastrich, K., Beauchamp, J. S., Mazzotti, F. J. & Heithaus, M. R. Effects of hydrology on the movements of a large-bodied predator in a managed freshwater marsh. Hydrobiologia 1–18 (2022).

Bunn, S. E. & Arthington, A. H. Basic principles and ecological consequences of altered flow regimes for aquatic biodiversity. Environ. Manage. 30, 492–507 (2002).

Castello, L., Isaac, V. J. & Thapa, R. Flood pulse effects on multispecies fishery yields in the lower Amazon. Royal Soc. open. Sci. 2, 150299 (2015).

Poff, N. L. Beyond the natural flow regime? Broadening the hydro-ecological foundation to Meet environmental flows challenges in a non‐stationary world. Freshw. Biol. 63, 1011–1021 (2018).

Winemiller, K. O. & Jepsen, D. B. Migratory Neotropical Fish Subsidize Food Webs of Oligotrophic Blackwater Rivers (University of Chicago Press, 2004).

Pereira, L. S., Tencatt, L. F. C., Dias, R. M., de Oliveira, A. G. & Agostinho, A. A. Effects of long and short flooding years on the feeding ecology of piscivorous fish in floodplain river systems. Hydrobiologia 795, 65–80 (2017).

Massie, J. A. et al. Long-term patterns in the relative abundance of Common Snook as a factor of shifting environmental conditions in the Florida coastal everglades. Mar. Coastal. Fisheries. 17, vtaf026. https://doi.org/10.1093/mcfafs/vtaf026 (2025).

Jepsen, D., Winemiller, K., Taphorn, D. & Olarte, D. R. Age structure and growth of Peacock cichlids from rivers and reservoirs of Venezuela. J. Fish Biol. 55, 433–450 (1999).

Jepsen, D. B., Winemiller, K. O. & Taphorn, D. C. Temporal patterns of resource partitioning among cichla species in a Venezuelan Blackwater river. J. Fish Biol. 51, 1085–1108 (1997).

Beerens, J. M., Gawlik, D. E., Herring, G. & Cook, M. I. Dynamic habitat selection by two wading bird species with divergent foraging strategies in a seasonally fluctuating wetland. Auk 128, 651–662 (2011).

Botson, B. A., Gawlik, D. E. & Trexler, J. C. Mechanisms that generate resource pulses in a fluctuating wetland. PloS One. 11, e0158864 (2016).

Cargnelli, L. M. & Gross, M. R. Fish energetics: larger individuals emerge from winter in better condition. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 126, 153–156 (1997).

Boucek, R. et al. An extreme climate event and extensive habitat alterations cause a non-linear and persistent decline to a well-managed estuarine fishery. Environ. Biol. Fish. 1–15 (2022).

Stevens, P. et al. Resilience of a tropical sport fish population to a severe cold event varies across five estuaries in Southern Florida. Ecosphere 7 https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1400 (2016).

Funding

Funding was provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers through a Cooperative Agreement through the South Florida - Caribbean Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit, and the National Science Foundation through the Florida Coastal Everglades Long Term Ecological program under Grant # DEB-2025954. We thank our collaborators at Everglades National Park, Florida International University (FIU), and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute for their support of our research. We thank Drs. John Kominoski, Elizabeth Anderson, and Rene Price at FIU for their contributions during manuscript revisions, and to two anonymous reviewers for their contributions during the peer review process. We also express thanks to the FIU University Graduate School for financial support provided to J. Massie during the early development of this manuscript through a Dissertation Year Fellowship, and to Coastal Carolina University for support during the final stages of analysis, writing, revision, and production. This is contribution #2067 from the Institute of Environment at Florida International University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. – Primary author of the main manuscript text and preparation of all figures and tables, formulation of research questions and hypotheses, data collection, interpretation, and analysis.R.R. – Major contributions to writing of manuscript, formulation of research questions and hypotheses, data analysis and interpretation of analyses.W.J. – Major contributions to writing of manuscript, formulation of research questions and hypotheses, and interpretation of analyses.R.S. – Major contributions to writing of manuscript, formulation of research questions and hypotheses, and interpretation of analyses.N.V. – Collected data used in analyses, field study implementation, provided feedback on intellectual content, and contributed to the writing and revisions of manuscript.R.B. – Collected data used in analyses, field study implementation, provided feedback on intellectual content, and contributed to the writing and revisions of manuscript.J.R. – Funding acquisition, study design, major contributions to writing of manuscript, formulation of research questions and hypotheses, field study implementation and data collection.All authors reviewed and approved the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The field procedures for animal subjects were ethically reviewed and approved by Florida International University’s Animal Care and Use Program under protocol numbers IACUC-20-057-CR01 and IACUC-21-003-CR01. Fish sampling was in accordance with IACUC protocol and was performed under the approved United States Department of the Interior National Park Service permit number EVER-2021-SCI-0050.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Massie, J.A., Rezek, R.J., James, W.R. et al. Linking a seasonal freshwater prey subsidy to the body condition of an estuarine consumer in a subtropical coastal river. Sci Rep 15, 41217 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25211-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25211-0