Abstract

To develop our proposed technology method to improve retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) detection in optical coherence tomography (OCT) images and compare its efficacy with Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm across multiple retinal diseases and healthy eyes. OCT images from 88 patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) were used for our proposed technology model training and validation. For testing with separate images were obtained from patients with AMD (100), diabetic retinopathy (DR; 50), epiretinal membrane (ERM; 50), branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO; 50), and healthy eyes (50). The proposed technology was used to identify RPE in OCT images using the Pyramid Scene Parsing Network on top of ResNet-50. The accuracy of the proposed technology method in RPE detection was measured using the mean absolute error (MAE) and compared with Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm for each retinal condition. As compared with Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm, the proposed technology showed significantly better MAEs across all conditions: AMD (2.18 vs. 4.79), DR (1.69 vs. 3.17), ERM (1.50 vs. 2.67), BRVO (1.86 vs. 2.98), and healthy eyes (1.59 vs. 2.28). Notably, the proposed technology’s superiority was most evident in the AMD group. The proposed technology method outperformed Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm in accurately visualizing RPE in OCT images across all tested conditions, especially in AMD. Our results indicate the proposed technology’s potential to elevate the RPE segmentation which can lead to enhancing ophthalmology care by providing more accurate OCT imaging analyses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Data obtained from noninvasive optical coherence tomography (OCT) are essential for the current diagnosis of retinochoroidal diseases and a deeper understanding of pathology. OCT technology provides similar images compared to histology because it can provide depth-resolved and registered images of retinal and choroidal tissue layers that can be tracked over time1,2. Therefore, OCT has transformed clinical practice, allowing ophthalmologists to diagnose and monitor the progression of retinal diseases3,4. In fact, based on tomographic images of retinas by OCT, many new findings in recent years have been reported for retinochoroidal diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD)5,6, diabetic retinopathy (DR)7,8, retinal vein occlusion (RVO)9,10, and epiretinal membrane (ERM)11,12.

AMD is a leading cause of blindness in industrialized nations13. As retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells age in AMD, they disrupt the balance of enzymes in the extracellular matrix of the macular region, leading to their accumulation on Bruch’s membrane14,15. The senescence of RPE cells causes immune cells to release vascular endothelial growth factor. AMD is characterized by the proliferation of blood vessels due to calcification, rupture, and phagocytosis of Bruch’s membrane16. In OCT, such changes can be observed by large drusen and elevation toward the RPE line and by fluid deposits, such as intraretinal cystoid fluid accumulation, subretinal fluid, and pigment epithelial detachment17.

Conversely, the development of ophthalmic imaging technologies leads to a growing volume and diversity of retina images, surpassing ophthalmologists’ ability to effectively segment these images17. Therefore, recent OCT models have a built-in algorithm allowing for automated segmentation of each layer of the retina14. Recent reports have shown that retinal layer segmentation and deep learning annotation are superior to conventional image-processing methods18,19,20,21. However, the accuracy of the segmentation becomes inadequate in heavily damaged or degenerated tissue, such as AMD22. Some methods have overcome this limitation but generally require an iterative process and are time-consuming19,23. Fang et al.19 also pointed out that this convolutional neural network is a specialized model for nonexudative AMD spectral domain OCT images and might not apply to retinal segmentation for other diseases. Moreover, according to Dabir et al.24, automatic segmentation showed low accuracy in identifying the correct RPE when analyzing OCT images of AMD patients with choroidal neovascular membranes, where the RPE line is often incorrect. This reason is likely attributed to abrupt changes in retinal layers, caused by structural alterations induced by disease, which weaken the probabilistic assignments of pixels to different classes20. Therefore, developing a method that can automatically and accurately segment AMD-associated RPE, such as our proposed technology method proposed in this study, could significantly enhance the screening and routine testing for large numbers of patients.

In this study, we compared the performance of our novel deep learning automatic segmentation method (the proposed technology method) to the conventional built-in OCT algorithm (Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm) using OCT images of various retinal diseases and those of normal eyes.

Results

We used 3352 OCT images from 88 patients with AMD. For mask images for testing, we could not identify the RPE lines in one patient with AMD. Therefore, we excluded this case (Table 1; Fig. 1).

Representative horizontal optical coherence tomography (OCT) image obtained by Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm showing a segmentation artifact and its corresponding image. (A) The green line shows the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) line identified by Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The red line shows the RPE line identified by the proposed technology method. In this AMD OCT image, there are parts where Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm cannot correctly detect the RPE line, but the proposed technology method can correctly detect it. (B) Original image corresponding to (A).

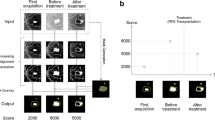

The median MAE values obtained for the AI method and Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm in RPE detection for each image group were as follows: AMD, 2.18 and 4.79; DR, 1.69 and 3.17; ERM, 1.50 and 2.67; BRVO, 1.86 and 2.98; and normal, 1.59 and 2.28. MAEs were significantly better with the proposed technology method than with Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm in all groups (P < .001; Table 2). Furthermore, the range in MAE improvement was smallest in the AMD group (Figs. 2 and 3).

Comparing the proposed technology and Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm in detecting retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) lines in optical coherence tomography images of normal and diseased eyes. The RPE line identified by the proposed technology method (red line) is almost similar to the actual RPE line, but the RPE line identified by Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm (green line) is slightly different from the actual RPE line. (A) The normal image, (B) original image corresponding to (A), (C) diabetic retinopathy, (D) original image corresponding to (C), (E) epiretinal membrane, (F) original image corresponding to (E), (G) branch retinal vein occlusion, (H) original image corresponding to (G), (I) age-related macular degeneration, and (J) original image corresponding to (I). The proposed technology method indicates that the RPE can be identified with higher accuracy in the normal image (A), diabetic retinopathy (C), epiretinal membrane (E), and branch retinal vein occlusion (G) rather than Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm. Also, on the age-related macular degeneration image (I), the RPE line identified by Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm at the lesion site significantly differs from the actual RPE line. However, using the proposed technology method, the RPE line is almost identical to the actual RPE line. Therefore, Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm may not be able to determine the RPE as accurately as the proposed technology methods.

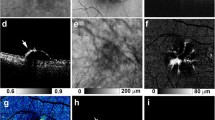

Figure 4 shows comparative images reconstructed from AMD tomographic images obtained from the RPE layer data visualized by the proposed technology and Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm using the RPE layer surface 3-dimensional reconstruction function built into the OCT device. Several small, elevated lesions on the RPE, which could not be visualized well using Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm, were more clearly visualized with the AI method. In addition, there was an instance in the AMD group in which Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm could not sufficiently detect the RPE line (Fig. 4).

Representative horizontal optical coherence tomography (OCT) of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) image and 3-dimensional reconstruction images (the proposed technology method, Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm). Representative horizontal OCT image of the left eye of AMD image (A) and the 3-dimensional surface of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) reconstructed by our proposed technology method (B) clearly shows small elevations, which were indistinguishable when using Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm (C). (D) Presented our proposed findings using an overlay and subtraction display method.

Discussion

The results of our study show that the proposed technology method was significantly more accurate in identifying RPE in OCT images of AMD than Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm. The proposed technology method also showed significantly higher accuracy in identifying RPE than Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm in images with DR, ERM, and BRVO, as well as in normal images without any lesions in the RPE. Prior studies25,26 indicate that the substantial diversity in features, encompassing not just blood vessels but also elements like exudates, cysts, or various pathological and non-pathological anomalies, frequently found in OCT imagery, significantly complicates the task of image segmentation, posing a considerable challenge. Furthermore, a different study27 highlighted that while DeepRetina can automate the segmentation of retinal layers, thus showing significant promise for the early detection of fundus retinal conditions, the task of achieving precise retinal layer segmentation is challenging due to the low resolution of retinal OCT images and disturbances caused by noise. Our results suggested that our proposed technology method using OCT devices in actual clinical practice may able to elevate the quality of ophthalmology care for various retinal diseases, including AMD.

Motozawa et al.28 reported that they developed and assessed the efficacy of two deep learning models, one for differentiating between normal and AMD-affected eyes using OCT images, and the other for categorizing AMD based on the presence or absence of exudative changes, achieving high classification accuracy in two cases. In our study, we investigated a method to more accurately detect RPE lines in various retinal diseases, including AMD. Therefore, our results demonstrated the possibility of not only distinguishing between normal retina and AMD but also more accurately capturing changes that may occur over time in various retinal diseases, including AMD. Hassan et al.29 suggested that their developed RFS-Net could be a promising diagnostic instrument for autonomously segmenting intraretinal fluid, subretinal fluid, and pigment epithelial detachment abnormalities. However, they only mention that this RFS-Net can grasp fluid with high accuracy. There is no discussion on whether this RFS-Net can correctly determine substantial elements like exudates. In fact, in a recent review30, most of the existing literature on Deep Learning (DL), AMD, and OCT predominantly focus on classification-related tasks, including identifying AMD, distinguishing AMD from various other macular disorders, and conducting detailed categorization of distinct AMD stages or characteristics. Therefore, our research with a more technical emphasis, primarily centered around segmentation using DL, prediction, forecasting, and utilization of multimodal imagery, can be a fundamental knowledge in utilizing DL-based predictive models as clinical decision support tools.

Fang et al.19 reported that their proposed method, a novel convolutional neural network and graph search-based method, could automatically perform segmentation of 9-layer boundaries on nonexudative AMD OCT images. However, those authors also pointed out that their learning-based method would need to be modified and customized in more challenging cases. Their approach is based on a regression method that assumes that the RPE line estimation is a constant value. This can mean that, for OCT images in which the RPE rises almost perpendicularly at a particular coordinate, such as images with exudative AMD, their method cannot accurately construct the elevated shape findings using only the tangent line as a clue. However, our proposed technology method learns various types of retinal lesion images and converts them into feature extraction patterns called filters. Therefore, the proposed technology method can recognize right-angled elevations, a characteristic of AMD, as one of the features and construct an image of it.31 Consequently, our proposed technology method maintains the accuracy of accurately constructing even in the case of OCT images where the RPE rises almost perpendicularly. These findings prompted further consideration of why PSPNet performed effectively in this task compared with other commonly used architectures such as U-Net. We selected PSPNet after comparison with general segmentation architectures, based on its suitability for the characteristics of OCT layer structures, particularly the OS/RPE boundary. The RPE complex often exhibits pathological alterations (e.g., drusen, pigment epithelial detachment, cystic changes) that require integration of global contextual information while preserving boundary precision on the order of only a few pixels. PSPNet, through its pyramid pooling module, explicitly aggregates multi-scale contextual information from global to local levels. In our implementation, we further modified the network by setting stride = 1 for conv2/conv5 and applying a 3 × 3 dilated = 2 convolution in conv5, maintaining an output stride of 16 while expanding the receptive field. This configuration enabled simultaneous preservation of the thin, highly curved boundary geometry and robust discrimination around diseased regions. In addition, the use of an Active-Contour loss (Region/Length with equal weighting) regularized boundary continuity and smoothness, reducing segmentation breaks. Experimentally, PSPNet consistently achieved lower MAE values than the conventional Topcon device algorithm across all disease groups (Table 2), with particularly notable improvement in AMD. In contrast, U-Net, though advantageous for local reconstruction via skip connections, lacks an explicit global pooling pathway and may therefore be less robust when long-range structural cues are critical. Collectively, the architectural design of PSPNet—its integration of multi-scale context, maintenance of spatial resolution, and boundary-aware optimization—aligns well with the demands of this task and the pathological characteristics of our dataset.

These fundamental differences in image construction methods contribute to higher performance by identifying distorted AMD RPE lines, including exudative AMD. Moreover, the results of our analysis using our proposed technology method were superior to those using Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm, even in the images of DR, ERM, and BRVO diseases, in which sudden and local RPE changes are unlikely to occur. Although normal RPE appears to be a smooth continuous curve, it could be a composite of irregular phases. If true, this could explain why our deep learning method produced a more realistic depiction of RPE than Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm, which tends to estimate linearly.

The degeneration of RPE is the most prominent anatomical feature of AMD, in which the pathophysiology is RPE damage due to neovascular development. A correct understanding of the pathogenesis of RPE directly improves the quality of AMD care32,33. One function of OCT is to provide a visually comprehensible representation of the partial elevations of RPE by 3-dimensionally reconstructing multiple cross-sectional images taken at regular intervals. The 3-dimensional surface of the RPE reconstructed by our proposed technology method clearly shows small elevations, which were indistinguishable when using the conventional methods. If the ophthalmologist carefully corrects the mechanically delineated RPE in multiple OCT images taken individually, it is possible to detect the slight elevation of RPE similarly to the proposed technology method, even using previously reported methods19. However, because such tasks require significant time and effort, this process is not viable because it is inefficient in a busy clinical practice. In general, DL has proven to be more effective than traditional approaches due to its ability to leverage a large team of experts and significant monetary investment, resulting in impressive precision across various domains34,35. The accurate and automated depiction of the pigment epithelial layer our method has made possible in this study will make it easier to understand the changes in the pigment epithelial layer in more detail in clinical practice. Furthermore, a more precise understanding of the pigment epithelial layer will significantly increase the accuracy of central retinal thickness36 and macular volume37, which are essential for the long-term management of AMD. If the proposed technology method can automatically and accurately delineate the RPE on each OCT image, then a precise and accurate understanding of the RPE surface image can be achieved in daily clinical practice.

Recent studies using deep learning have reported notably lower segmentation errors than conventional algorithms when evaluated on controlled datasets. For example, Sousa et al.21 reported a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.57 pixels for RPE segmentation in intermediate AMD using a U-Net–based architecture, and Morelle et al.38 achieved an average absolute distance of 0.85 pixels for RPE segmentation on an AMD dataset using a residual encoder–decoder network. Although our median MAE values (≈ 2 pixels for AMD) were higher than those reported in these studies, several factors may account for this difference. First, the ground truth in our study was manually annotated by a single orthoptist, introducing possible systematic bias and inter-observer variability absent in multi-annotator datasets. Second, our dataset was acquired exclusively with a swept-source OCT device (Topcon DRI OCT-1 Atlantis) that has different axial and lateral resolutions and pixel scaling compared with the spectral-domain devices used in other studies. Third, our PSPNet-based architecture was optimized to balance global contextual integration and local boundary preservation across multiple retinal pathologies, rather than to minimize sub-pixel-level MAE in AMD alone. These considerations suggest that the observed differences in MAE reflect variations in dataset composition, resolution, and annotation procedures rather than inferior algorithmic accuracy. Accordingly, we have revised our discussion to clarify that our method demonstrated superiority only relative to the conventional Topcon automated segmentation algorithm, not over all previously reported deep learning models.

This study had some limitations. First, the ground truth for all 3,352 training images was annotated by a single orthoptist. Although the annotator was trained and supervised by a retinal specialist, the use of a single annotator may introduce systematic bias in the delineation of the RPE boundary. Inter-observer variability is an important factor in manual annotation, and future studies should incorporate multiple annotators and consensus labeling to minimize potential bias and enhance reproducibility. Second, the training data consisted exclusively of OCT images from patients with AMD. Nevertheless, our model demonstrated strong generalization performance when applied to images of other retinal diseases such as DR, ERM, and BRVO. This finding suggests that the model successfully captured fundamental morphological characteristics shared across different retinal pathologies, such as smoothness, curvature, and continuity of the RPE layer, rather than features specific to AMD alone. This cross-disease generalizability indicates that PSPNet’s multi-scale contextual learning can extract robust structural representations applicable to various retinal conditions. Second, this was a single-center study. Ideally, multiple institutions would implement the system, and a study would be conducted with larger sample sizes and a greater number of images. Third, the present study is limited to detection of only the RPE layer. A team from Moorfield Hospitals in the United Kingdom and Google reported that they successfully identified various lesions in each layer of the retina using the same OCT equipment as employed in our current study39. However, although much time has passed since that report, the validation of the results is ongoing, and there are no reports of its practical application. The main goal of our study was not to create an AI for OCT that makes diagnoses and decisions on physicians’ behalf but to improve its accuracy to increase its efficiency in daily clinical practice. This system has been successfully implemented in our hospital as a GPU machine attached to the OCT device.

In conclusion, we developed the proposed technology method to improve RPE detection using the globally accepted OCT device and compared its performance with Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm using OCT images of multiple retinal diseases and normal eyes. Our results showed that in all image groups of AMD, DR, ERM, BRVO, and normal eyes, RPE detection by the proposed technology method was significantly more accurate than Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm. Compared with Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm, the proposed technology method’s improvement was particularly significant in the AMD group. The proposed technology method was superior to Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm though not directly comparable to other deep-learning models for more accurate identification of RPE and is expected to be widely implemented in the future.

Methods

Study design and overview

In this retrospective, single-center, cross-sectional study, OCT images were taken between December 20, 2019, and June 1, 2022, at the Tsukazaki Hospital Department of Ophthalmology and were extracted from images stored in the Tsukazaki Hospital Ophthalmology Database. The Ethics Committee of Tsukazaki Hospital approved the study, which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent. The participants were not offered incentives or compensation to participate. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. We excluded OCT images showing multiple retinal diseases and poor-quality images due to intermediate translucent opacity.

We included in the study OCT images (DRI OCT-1 Atlantis, Topcon, Tokyo) of patients that showed any 1 of the following retinal diseases: AMD, DR, ERM, or branch RVO (BRVO), confirmed by an ophthalmologist, and OCT images of normal retinas (“normal”) without any retinal diseases. DRI OCT-1 Atlantis is a swept light source OCT for fundus imaging at a wavelength of 1,050 nm. The imaging protocol was cross scan (6 mm, horizontal and vertical B-scans with 1024 A scans each). All OCT images were taken using this OCT, then cross scans on the fovea were performed by trained certified orthoptists.

The proposed technology model

An orthoptist trained by a retinal specialist identified the upper bounding surface of the RPE complex on the extracted 3352 OCT images of 88 patients with AMD (67 men and 21 women; mean age, 75.3 ± 10.7 years). We then used image-processing software (Photoshop, Adobe, US) to create mask image (3352 images) to train our proposed technology model (Fig. 5). The orthoptist annotated the RPE boundaries on each training mask image (3,352 images) using a graphics tablet (LIFEBOOK WU3/F3; Fujitsu Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) within Photoshop (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Following a consistent rule, the region from the upper edge of the RPE to the lower border of the choroid was labeled white, and all other regions were labeled black. We created an RPE line identification model using the Pyramid Scene Parsing Network (PSPNet)40. The PSPNet model uses an adaptive pooling strategy to concurrently extract feature maps from different regions of an image and pool them to provide semantic segmentation. This aggregation helps the model understand both fine and large-scale context.

Representative horizontal optical coherence tomography (OCT) image of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) image, its mask image and its overlays the original image with the mask. (A) Representative horizontal OCT image of the left eye of AMD. (B) An image based on image A with the region between the upper bounding surface of retinal pigment epithelium and the chorioscleral interface masked (8-bit grayscale, background intensity value of 0, and masked region intensity value of 1). (C) An image showing the region where the original image and the mask are overlaid, highlighted in red.

Its ability to handle multi-scale feature extraction and enhance contextual awareness makes it particularly effective for segmenting complex fundus OCT images, where feature sizes vary significantly and distinguishing between background and foreground is challenging41,42.

Of these 3352 images obtained from 88 patients, 3024 images from 82 patients were used for training, and 328 images from 6 patients were used for validation. Images were divided so that the image data from the same patient were not included in the training and validation sets. We also created mask images to test the proposed technology model by performing 1 scan (macular fixation, cross-scan) and obtaining 2 images from each patient whose OCT images were not included when the proposed technology model was created. We created mask images for the following image groups and the number of images: AMD, 200 images from 100 patients (71 men and 29 women; mean age 75.6 ± 8.4 years); DR, 100 images from 50 patients (35 men and 15 women; mean age 64.6 ± 10.8 years); BRVO, 100 images from 50 patients (29 men and 21 women; mean age 74.3 ± 12.4 years); ERM, 100 images from 50 patients (28 men and 22 women; mean age 72.0 ± 5.4 years); normal, 100 images from 50 participants (26 men and 24 women; mean age 72.0 ± 8.2 years).

For the test dataset, B-scan images were randomly selected from patients whose images were not used for training or validation. The same inclusion and exclusion criteria as those applied to the training dataset were adopted, and random sampling was repeated until the required number of images was obtained. Image IDs were carefully checked to ensure no overlap with those used in the training dataset, thereby minimizing any potential selection bias.

Network architecture

We used the PSPNet on top of ResNet-50.40,43 To expand the receptive field without reducing the resolution of the feature map, we laid 2 variations over it. First, the strides of conv2 and conv5 were 1. Second, the kernel size of 3 × 3 convolution layers in conv5 were dilated by a factor of 2.44 Thus, the feature map size was 1/16 of the input image. For the pyramidal pooling module, we used a 4-level pooling module with bin sizes of 1 × 1, 2 × 2, 3 × 3, and 6 × 6, with an average pooling operation. The output of each pooling layer was followed by a 1 × 1 convolution layer to reduce the channel dimension to 512 and then up-sampled to yield a size feature similar to the original feature map via bilinear interpolation. The different feature levels were concatenated to comprise the final feature map. Two 2-dimensional convolution layers followed the final feature map to generate a final prediction that had the same size as the input image (Fig. 6).

We trained the model with the Adam optimizer using a SoftMax layer and active contour (AC) loss with equal weights for Region and Length for up to 100 iterations on a single graphics processing unit (GPU)45. The initial learning rate was 0.0002 and was attenuated by dividing by 2 after every 5 iterations. If the AC loss of the validation set did not improve over 10 iterations, we stopped the training and retrieved the weight with the minimum AC loss. All of the above parameters were determined based on their validation set performance.

We augmented the data by jointly applying affine and elastic transformations over the inputs and ground truth segmentations to improve the generalization abilities of our model. We also applied intensity transformations and additive Gaussian noise over inputs. As data augmentation techniques, we randomly applied horizontal flipping, affine transformation, brightness and contrast adjustment, gamma correction, and Gaussian noise.

Evaluation and statistical analysis

For mask images for testing, the boundary detection between the outer segment tip (OS)/RPE was performed using Topcon Advanced Boundary Segmentation methods (version 1.6.1.8)6 and the artificial intelligence boundary segmentation model. The mean absolute error (MAE) of the identified position was obtained in pixel units for the identified position on the mask images. The MAE was visualized using a box plot to compare the MAE between the proposed technology and conventional methods for each disease. The upper edge of the annotation mask’s Y-coordinate was evaluated as the RPE layer’s ground truth (y_i), and the MAE was calculated as the average of the absolute difference (d_i) between this and the Y-coordinate (y′ _i) computed as the result of conventional segmentation by Topcon or inference by PSPNet (Figs. 7 and 8). We determined the MAE using the formula below:

Representative horizontal optical coherence tomography (OCT) image of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) identification and its corresponding image. (A) Representative horizontal OCT image of the left eye of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) showing the identification of RPE using the proposed technology and conventional methods. The green line shows the RPE line identified by the conventional method. The red line shows the RPE line identified by the proposed technology method. In this AMD OCT image, there are parts where Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm could not correctly detect the RPE line, but the proposed technology method did. (B) Original image corresponding to (A).

Calculation of mean absolute error between ground truth and topcon/pyramid scene parsing network per image. The upper edge of the annotation mask’s Y-coordinate was evaluated as the retinal pigment epithelium layer’s ground truth (y_i) (red line), and the mean absolute error was calculated as the average of the absolute difference (d_i) between this and the Y-coordinate (y′_i) computed as the result of conventional segmentation by Topcon or inference by Pyramid Scene Parsing Network (green line).

To determine whether the proposed technology model’s OS/RPE boundary identification has a significantly smaller MAE than Topcon’s automated segmentation algorithm, we conducted a one-sided test for each patient using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (Python version 3.9.10, SciPy version 1.8.0). P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Keane, P. A. et al. Evaluation of age-related macular degeneration with optical coherence tomography. Surv. Ophthalmol. 57, 389–414 (2012).

Guymer, R. H. et al. Incomplete retinal pigment epithelial and outer retinal atrophy (iRORA) in age-related macular degeneration: CAM report 4. Ophthalmology 127, 394–409 (2020).

AttaAllah, H. R., Mohamed, A. A. M. & Ali, M. A. Macular vessels density in diabetic retinopathy: quantitative assessment using optical coherence tomography angiography. Int. Ophthalmol. 39, 1845–1859 (2019).

Dong, Y. et al. Association of optical coherence tomography and optical coherence tomography angiography retinal features with visual function in older adults. JAMA Ophthalmol. 140, 809–817 (2022).

Waldstein, S. M. et al. Characterization of Drusen and hyperreflective foci as biomarkers for disease progression in age-related macular degeneration using artificial intelligence in optical coherence tomography. JAMA Ophthalmol. 138, 740–747 (2020).

Zekavat, S. M. et al. Photoreceptor layer thinning is an early biomarker for age-related macular degeneration: epidemiologic and genetic evidence from UK biobank OCT data. Ophthalmology 129, 694–707 (2022).

Lois, N. et al. Evaluation of a new model of care for people with complications of diabetic retinopathy: the EMERALD study. Ophthalmology 128, 561–573 (2021).

Gurudas, S. et al. Multicenter evaluation of diagnostic Circulating biomarkers to detect sight-threatening diabetic rretinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 140, 587–597 (2022).

Scott, I. U. et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes after anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for macular edema in participants with hemiretinal vein occlusion compared with participants with central retinal vein occlusion: study of comparative treatments for retinal vein occlusion 2 (SCORE2) report 18. JAMA Ophthalmol. 140, 458–464 (2022).

Yiu, G. et al. Predictors of as-needed Ranibizumab injection frequency in patients with macular edema following retinal vein occlusion. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 249, 74–81 (2023).

Wang, L. C. et al. Correlations between clinical and histopathologic characteristics in idiopathic epiretinal membrane. Ophthalmology 129, 1421–1428 (2022).

Shin, D. Y. et al. Fluctuation of intraocular pressure and vascular factors are associated with the development of epiretinal membrane in glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 254, 69–79 (2023).

Flaxman, S. R. et al. Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990–2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 5, e1221–e1234 (2017).

Del Priore, L. V., Kuo, Y. H. & Tezel, T. H. Age-related changes in human RPE cell density and apoptosis proportion in situ. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 3312–3318 (2002).

Ciulla, T. A. Evolving pathophysiological paradigms for age related macular degeneration. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 85, 510–512 (2001).

Deng, Y. et al. Age-related macular degeneration: epidemiology, genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and targeted therapy. Genes Dis. 9, 62–79 (2022).

Dodo, B. I., Li, Y., Eltayef, K. & Liu, X. Automatic annotation of retinal layers in optical coherence tomography images. J. Med. Syst. 43, 336 (2019).

De Fauw, J. et al. Clinically applicable deep learning for diagnosis and referral in retinal disease. Nat. Med. 24, 1342–1350 (2018).

Fang, L. et al. Automatic segmentation of nine retinal layer boundaries in OCT images of nonexudative AMD patients using deep learning and graph search. Biomed. Opt. Express. 8, 2732–2744 (2017).

Mukherjee, S. et al. Retinal layer segmentation in optical coherence tomography (OCT) using a 3D deep-convolutional regression network for patients with age-related macular degeneration. Biomed. Opt. Express. 13, 3195–3210 (2022).

Sousa, J. A. et al. Automatic segmentation of retinal layers in OCT images with intermediate age-related macular degeneration using U-Net and DexiNed. PLOS ONE. 16, e0251591 (2021).

de Sisternes, L. D., Hu, J., Rubin, D. L. & Marmor, M. F. Localization of damage in progressive hydroxychloroquine retinopathy on and off the drug: inner versus outer retina, parafovea versus peripheral fovea. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 56, 3415–3426 (2015).

de Sisternes, L. et al. Automated intraretinal segmentation of SD-OCT images in normal and age-related macular degeneration eyes. Biomed. Opt. Express. 8, 1926–1949 (2017).

Dabir, S. et al. Need for manual segmentation in optical coherence tomography angiography of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. PLOS ONE. 15, e0244828 (2020).

González-López, A., de Moura, J., Novo, J., Ortega, M. & Penedo, M. G. Robust segmentation of retinal layers in optical coherence tomography images based on a multistage active contour model. Heliyon 5, e01271 (2019).

Kepp, T. et al. Segmentation of retinal low-cost optical coherence tomography images using deep learning. SPIE Med. Imaging. arXiv2001.08480v1 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. DeepRetina: layer segmentation of retina in OCT images using deep learning. Transl Vis. Sci. Technol. 9, 61 (2020).

Motozawa, N. et al. Optical coherence tomography-based deep-learning models for classifying normal and age-related macular degeneration and exudative and non-exudative age-related macular degeneration changes. Ophthalmol. Ther. 8, 527–539 (2019).

Hassan, B. et al. Deep learning based joint segmentation and characterization of multi-class retinal fluid lesions on OCT scans for clinical use in anti-VEGF therapy. Comput. Biol. Med. 136, 104727 (2021).

Koseoglu, N. D., Grzybowski, A. & Liu, T. Y. A. Deep learning applications to classification and detection of age-related macular degeneration on optical coherence tomography imaging: a review. Ophthalmol. Ther. 12, 2347–2359 (2023).

Menteş, J. & Yıldırım, Ş. Optical coherence tomography characteristics of quiescent type 1 neovascularization in eyes with nonexudative Age-related macular degeneration. Turk. J. Ophthalmol. 49, 84–88 (2019).

Borrelli, E. et al. Postreceptor neuronal loss in intermediate age-related macular degeneration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 181, 1–11 (2017).

Vujosevic, S. et al. Quantitative choriocapillaris evaluation in intermediate age-related macular degeneration by swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography. Acta Ophthalmol. 97, e919–e926 (2019).

Diao, S. et al. Classification and segmentation of OCT images for age-related macular degeneration based on dual guidance networks. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 84, 104810 (2023).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Schmidt-Erfurth, U. & Waldstein, S. M. A paradigm shift in imaging biomarkers in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 50, 1–24 (2016).

Chakravarthy, U. et al. Impact of macular fluid volume fluctuations on visual acuity during anti-VEGF therapy in eyes with nAMD. Eye 35, 2983–2990 (2021).

Morelle, O. et al. Accurate Drusen segmentation in optical coherence tomography via order-constrained regression of retinal layer heights. Sci. Rep. 13, 8354 (2023).

Moraes, G. et al. Quantitative analysis of OCT for neovascular age-related macular degeneration using deep learning. Ophthalmology 128, 693–705 (2021).

Zhao, H., Shi, J., Qi, X., Wang, X. & Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proc 30th IEEE Conf Comput Vis Pattern Recognition. 6230–6239 (2017).

Safai, A. et al. Quantifying geographic atrophy in Age-Related macular degeneration: A comparative analysis across 12 deep learning models. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 65, 42 (2024).

Danilov, V. V. et al. ML-driven segmentation of microvascular features during histological examination of tissue-engineered vascular grafts. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 12, 1411680 (2024).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 770–778 (2015).

Yu, F. & Koltun, V. Multi-scale context aggregation by dilated convolutions; (2015).

Chen, X. et al. Learning active contour models for medical image segmentation. In 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 11624–11632 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The orthoptists of Tsukazaki Hospital contributed to the collation of the data. We would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study, HT and DN; data analysis and interpretation, MT; writing of the article, HT and DN; critical revision of the article, HT, DN, MT, KM, NI, DK and KA; final approval of the article, HT, DN, MT, KM, NI, DK and KA; data collection, KM and NI.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tabuchi, H., Nagasato, D., Tanabe, M. et al. Evaluation of deep learning-based retinal pigment epithelium segmentation for a widely used optical coherence tomography device. Sci Rep 15, 41310 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25221-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25221-y