Abstract

The “Forest Village” model utilizes forests as a central medium, leveraging rural forest resources as a key asset for rural revitalization. Taking 1140 national forest villages in Southwest China as the research object, the spatial distribution characteristics of national forest villages in southwest China were analyzed from two dimensions, nature and village nature, using ArcGIS 10.8 tools with watersheds as the research unit. The two dimensions of nature and society and their influencing factors were identified by using a combination of methods such as spatial autocorrelation, the closest neighbor index, the standard deviation ellipse, kernel density analysis and OPGD. The results revealed the following: (1) It is sparsely in the west and densely in the east, featuring four high—density cores that radiate outward to the surrounding areas. (2) The most significant among these factors are socio—economic ones, such as GDP density and population density, which demonstrate the notable impact of human disturbances on rural distribution. (3) Among the natural factors, topography and climate exert the most significant influence. Among the remaining factors, the densities of the river network and road network are strongly influenced by urban development, showing a high degree of alignment with the distribution of other social factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

National forest villages refer to ecologically livable villages with excellent performance in terms of well-preserved natural ecological landscape, distinctive characteristics of native fields, prominent forest landscape, remarkable ecological functions, developed forestry industry, beautiful human habitat, and sound management mechanism, etc. As an important carrier of Chinese excellent traditional culture and a model of ecological civilization construction, national forest villages play a key role in the strategy of rural revitalization. However, these villages are facing serious challenges with the advancement of new urbanization: the hollowing out of villages has intensified, urban elements have impacted the original living space within villages, the agricultural production function has become dysfunctional, and the ecological environment has gradually fragmented, and these changes have posed a threat to the sustainable development of the national forest villages1. Therefore, ecological revitalization and environmental governance have become an important part of rural ecological revitalization, as one of the core connotations of rural revitalization, and also an important hand in solving the “three rural” problem(concerning agriculture, rural areas and farmers)2,3; and the development of ecological civilization construction can promote the development of green economy in the countryside, and transform the natural ecological advantages of the countryside into economic benefits.

The study of village morphology originated in Europe in the 1840–1940s, focusing mainly on the impact of natural and man-made environments on village morphology4. The lines separating urban and rural areas have become increasingly hazy due to the progressive complexity, diversity, and high fragmentation of peri-urban landscapes brought about by the steady development of urbanization and rural lifestyles’ difficult transition to urban living processes5. However, the trend of rural construction toward economic development has led to an increase in the waste of land resources, ecological degradation, and constructive destruction. This could exacerbate the polarization of agricultural intensification and abandonment between developed and remote areas6. Conflicts between ecological preservation and economic growth continue to exist in environmentally fragile and distant undeveloped villages, and some villages with declining environmental conditions and low land-use rates have progressively vanished as society has progressed. Among other advantages, villages nearer to the city have more developed green infrastructure and can benefit from the city’s transit convenience. Their development patterns are also influenced by the metropolis7. These have caused academics’ attention to gradually turn toward the effects of urban expansion on rural areas and to include eco-habitat issues in their study agendas. Concepts like eco-village (Robert Gilman,1991), green-village (Evaluation standard of green village, 2022), low carbon community (Japan 2050 Low-Carbon Society Scenario Team, 2008), and other ideas have been put forth to link the individual and the society, to gradually transform people’s traditional lifestyles into sustainable lifestyles through various energy-saving and emission-reduction green measures. This is due to the gradual inclusion of psychological research into the scope of urban planning and rural planning.

The early Green Village and Ecological Village concepts are comparable to the idea of a “forest village”. In China, the research of rural geography has entered a period of vigorous developmentsince the program of “China’s beautiful countryside” was launched in Zhejiang in 2008. Although “forested countryside” belongs to the “beautiful countryside” category, it focuses on the natural landscape resources and forest resource endowment8. All forms of villages, including eco-villages, forest-village, and green-village, are intricately linked to the surrounding natural environment. All of them are designed to establish sustainable environments, with an emphasis on restoring and balancing the natural world and protecting the four material circulation systems that support human life—soil, water, and plants.

With the goal of building forest villages, increasing forest coverage, utilizing all of the abundant forest resources that serve as the foundation for these villages, and creating ecologically sustainable forest villages, China developed the Measures for the Evaluation and Recognition of National Forest Villages and its evaluation indicators in 20199. The first list of national forest villages was released in the same year, and there have been two batches of national forest villages with a total of 7586 villages selected for the list up to now. National forest villages can be built to maximize their aesthetic value and to create a stunning, livable rural setting. There are about 40% of China’s population lives in rural areas. Although the development of rural areas lags behind that of urban areas, the rural revitalization strategy implemented by the country in recent years has brought great opportunities for rural development.

The southwestern region of China features diverse topography and landforms, complex forest types, pronounced vertical climatic variations, and a multitude of ethnic groups. However, rural infrastructure and living conditions in this area remain relatively underdeveloped. The development of tourism has brought both opportunities and challenges to rural areas. This study focuses on the southwestern region of China, examining the spatial distribution characteristics of 1140 national-level forest villages in this area. It constructs a corresponding indicator system to reveal influencing factors and employs the optimal geographical detector method for quantitative and qualitative analysis of the driving factors affecting forest village distribution. Finally, it proposes recommendations for the conservation and development of forest villages. The research findings can, to a certain extent, promote the conservation of forest villages in the southwestern region, advance sustainable village development, and provide a reference basis for future forest village assessment and decision-making. Additionally, it is hoped that this study will offer insights for the sustainable development of forest villages in other countries and regions.

Materials and methods

Study area

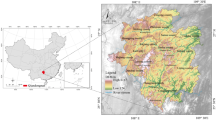

The Southwest region is one of the seven natural geographical divisions of China, including Chongqing Municipality, Sichuan Province, Guizhou Province, Yunnan Province, and the Tibet Autonomous Region, a total of five provinces and municipalities. These areas are uniformly known as the five southwestern provinces, with a total area of 2340,600 km2, accounting for 24.5% of China’s land area. The southwest region occupies a unique geographic area that stretches from the Tibetan Plateau in the south to the tropical rainforests in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan Province, and from the Himalayas in the west to the Sichuan Basin and the upper reaches of the Yangtze River. The region’s large height variation has produced a variety of weather zones as well as abundant biological, mineral, and hydropower resources (Fig. 1).

Climatic conditions

Climatic conditions constitute a highly significant factor in spatial analysis, particularly in rural areas where the impacts of climate must be taken into account10.

Temperature

The substantial elevation disparities in the southwest region give rise to diverse climatic zone types. Due to the uplift of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, there are significant variations in both temperature and precipitation from northwest to southeast in this area. The eastern part records an average annual temperature of up to 24 °C, while the western part can see the lowest average annual temperature drop below 0 °C, with highly uneven temporal and spatial distributions11. Generally, this region can be categorized into three climatic types: subtropical monsoon climate, marine climate, and plateau climate.

Precipitation

The complex topography in the southwest region results in highly uneven precipitation distribution. The Sichuan Basin experiences notably higher precipitation compared to its surrounding areas. Meanwhile, most other parts of the southwest region exhibit distinct dry and rainy seasons. Spring precipitation shows an increasing trend from west to east, whereas summer precipitation declines from south to north. In autumn, precipitation patterns tend to be more similar across the region12.

Sunshine duration

The intricate topographical structure of the southwest region also leads to significant variations in sunshine duration. Areas with longer sunshine hours are primarily distributed across the higher-elevation regions, including the Tibetan Plateau, Hengduan Mountains, and Yunnan Plateau. In contrast, the Guizhou Plateau and Sichuan Basin experience relatively shorter sunshine durations.

Data sources and data processing

The lists of two batches of national forest villages within the scope of this study, the locations of local municipal and prefectural governments, as well as provincial administrative divisions, were obtained from the official website of the Chinese government (https://www.gov.cn).

Based on commonly employed indicators in prior village research (e.g., elevation, aspect, slope gradient, population density, per capita GDP, road density, and hydrological networks), and aligned with the evaluation criteria for forest villages, three supplementary indicators were integrated: NDVI, mean annual temperature, and precipitation. These were systematically organized into two primary categories and ten subcategories, yielding a robust indicator framework. Refer to Table 1 for the constructed influencing factor system and data sources.

Methods

Spatial autocorrelation

Utilize ArcGIS 10.8 for calculating the Global Moran’s I.Given a set of elements and associated attributes, Global Moran’s I determines whether the pattern expressed is clustered, discrete, or random. The tool assesses the significance of the index by calculating Moran’s I index value, z-score, and p-value. The Global Moran’s I index was calculated as follows.

where n represents the number of watersheds at the third-level, Xi (Xj) represents the total number of national forest villages in watershed i (j); \(\overline{x }\) represents the mean valve of the number of forest villages in the total watersheds; Wij represents the selection weights between watersheds i and j. The value of Moran’s I index ranges from − 1 to 1, and a positive I indicates positive spatial correlation, the larger the I value, the more obvious the spatial correlation; a negative I indicates negative spatial correlation, the smaller the I value, the larger the spatial difference; I = 0 indicates that there is no spatial correlation.

where \({Z}_{i}={y}_{i}-\overline{y }\), \({Z}_{j}={y}_{j}-\overline{y }\), \({S}^{2}=\frac{1}{n}\sum {\left({y}_{i}-\overline{y }\right)}^{2}\), \({w}_{ij}\) represent the value of spatial weights, n represents the total number of all districts on the study area, and LISAi represents the local Moran’s I of watershed i.

Based on the positive or negative values and statistical significance of the local Moran’s I, the LISA cluster map divides spatial units into four types (Table 2).

Kernel density analysis

Kernel density is commonly used to calculate the unit density of point and line element measurements within a specified domain, which can visualize the spatial clustering and dispersion of analytical targets.

For

where I = 1, 2. . ., n are the input points. Disti represents the distance between point i and (x, y) position.

The ArcGIS 10.8 software was used to calculate the kernel density of the first and second batches of forest villages as well as the overall kernel density of all the forest countryside. The results of the calculations were divided into five grades using the natural breakpoint method to have a more direct understanding of the distribution characteristics of the forest villages in the southwest region.

Voronoi diagram

The Voronoi Diagram is a method of dividing the plane proposed by the Ukrainian mathematician George Voronoi. This method divides the plane into regions based on a given set of “seed points”, where all points in each region are closer to the seed point of that region than to any other seed point. Due to the equidistant characteristics of the Voronoi diagram in spatial partitioning, it can be used to solve problems such as the nearest point, the minimum enclosing circle, and many spatial analysis problems, such as adjacency, proximity, and accessibility analysis. The thesis established Voronoi polygons for the overall distribution of forest villages in the southwest region, which to a certain extent can reflect the distribution characteristics and dense areas of the villages.

Spatial statistic

The Spatial Statistic are commonly used to summarize the spatial characteristics of geographic elements: central tendency, discrete, and directional tendency. The Spatial Statistic was calculated as follows.

The Standard Deviation Ellipse tool creates a new output element class in which each case corresponds to an ellipse surface. The attribute values for these ellipsoids will include the X and Y coordinates of the mean center, the two standardized distances (long and short axes), and the orientation of the ellipse. In addition to generating the ellipse, the following results are given: Shape-leng and Shape-Aera are the perimeter and area of the generated ellipse; Center X and Center Y represent the center of the ellipse; XStdDist and YStdDist represent the length of the X-axis and the length of the Y-axis; and Rotation represents the direction and angle of the ellipse. Rotation is the direction of the ellipse.

Optimal parameters-based geographical detectors (OPGD)

Geodetectors are a set of statistical methods for detecting spatial dissimilarities, as well as revealing the driving forces behind them. In OPGD, parameter optimization consists of spatial discretization optimization and spatial scaling optimization, providing a combination of a set of discretization methods and breakpoints for each continuous variable to compute the respective q-value.

where L represents the number of layers divided by a factor; \({N}_{h}\) and \(N\) represent the number of forest villages in layer h and the whole region, respectively; \({{\sigma }_{h}}^{2}\) and \({\sigma }^{2}\) represent the variance of the kernel density valves of forest villages in layer h and the whole region, respectively; and the q-value ranges from 0 to 1; the larger the q-valve is, the stronger the explanatory power of the factor on the distribution of forest villages.

A larger q-value represents a higher significance of the explanatory variables because of low variance within subregions and high variance between subregions. In OPGD, at least two samples per stratum are required to calculate the mean and variance values.

River network buffer

Rivers above the third-level in Southwest China were selected to extract the objects, and 5 km, 10 km, 15 km, and 20 km were chosen as the buffer distances ArcGIS10.8 was used to calculate buffer zones of each third-level river and superimpose the analysis with forested village sites in Southwest China to compare the distribution characteristics of the villages under the rivers of different magnitudes.

Road network buffer

Using ArcGIS 10.8 software, we clipped out the transportation system in southwest China, encompassing key transportation routes such as provincial highways, national highways, expressways, and railways. We then overlaid the locations of forest villages and established buffer zones at radii of 5 km, 10 km, 15 km, and 20 km. Subsequently, we calculated the number of forest villages within each buffer zone to analyze the impact of the road network on the distribution of forest villages.

Results

Spatial autocorrelation

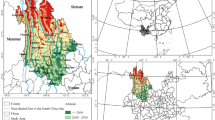

Based on the positive or negative values and statistical significance of the local Moran’s I, the study area contains three types of clusters: HH, LL, and LH. According to the LISA (Fig. 2), a total of 8 third-level watersheds fall into the HH-type distribution, with approximately 48% of the forest villages located within these watersheds, and these HH-type watersheds together make up a bigger cluster of HH-type watersheds. It is located at the confluence of a first- and second-level river and contains one first-level watershed and two second-level watersheds, which are subdivided into nine third-level watersheds. The Yangtze River watershed is the first-level watershed among them, and the Yangtze River mainstream watershed, Yalong River watershed, Jialing River watershed, Min River watershed, and Xijiang River watershed are the second-level watersheds. On this basis, it is subdivided into third-level watersheds: the mainstream watershed below Shigu, the Qingyi-Minjiang River watershed, the Tuojiang River watershed, the Chishui River watershed, the Yibin-Yichang mainstream watershed, and the Beipanjiang River watershed. Almost half of all forest villages in the Southwest are dispersed within HH-type watershed clusters.

The LL-type distribution is mainly in the northern and central regions of the Tibetan Plateau, and there are only 26 forest villages within these regions, accounting for 2.28% of the total. The LL-type area contains two large second-level watersheds, the Qiangtang Plateau instream flow area and the Brahmaputra watershed, under which are divided into three third-level watersheds: the Qiangtang Plateau area watershed, the Lhatse-Paixiang watershed, and the southern TibetRivers watershed. There are very few forest villages distributed within the LL-type area but show a clear tendency of clustering in the vicinity of the Niyangtse in the Qiangtang Plateau instream flow area, as well as in the southern TibetRiver watershed.

The LH-type distribution is presented in the figure as two small areas, both immediately adjacent to the HH-type watershed cluster distribution. These two small-scale areas are the sub-Sinan watershed of the Wujiang River and the Hongshui River watershed, which belong to the two major secondary watersheds, accounting for 44.96% and 13.43% of the watershed, respectively. The region has 46 forest villages in total, with significantly fewer villages in these two small areas than in the neighboring HH-type third-level watershed agglomeration area and the non-significant third-level watershed area, resulting in a numerical trend of “low-lying” villages.

There are 48.07% of the total forest villages are located in HH-type watershed clusters, and another 72 forest villages are located in LL-type and LH-type watersheds, with all of the villages in these three types of watersheds amounting to 54.39% of the total number of villages in the southwest area. The remaining villages are all located in watersheds that do not have distinctive features, and these areas are divided into a continuous, wide-ranging cluster of watersheds, which are concentrated between the HH-type watershed group and the LL-type watershed group, including seven second-level watersheds: the Jialing River watershed, the Minjiang River watershed, the Yalong River watershed, the Nujiang River watershed, Lantsang River watershed, Yuanjiang-Honghe River watersheds, and the southwestern portion of the Xijiang River watershed, with 17 third-level watersheds under their jurisdiction. There are also three small watershed clusters with insignificant distributional characteristics, one of which is in the south-western part of the LL-type watershed cluster, including the Shiquan River watershed and a portion of the western part of the Brahmaputra watershed, which contains two third-level watersheds, namely the western rivers of Tibet and the lower part of the Lazhi section of the Brahmaputra. The last one is in the east, surrounded by the HH-type and LH-level clusters, containing the Wu River watershed, the Xijiang River watershed, and the Dongting Lake watershed, with three third-level watersheds under their jurisdictions. The forest settlements in the region are more evenly spread, with a total of 45.61% (Five hundred and twenty).

Characteristics of spatial aggregation

The average nearest neighbor index is a statistical indicator used to measure the uniformity and clustering degree of spatial point patterns. It measures the clustering degree of the pattern by calculating the ratio of the average distance from each point to its nearest neighbor to the average distance between points in an ideal uniform distribution. By calculating the GIS average nearest neighbor index, we can help understand and describe the clustering nature of spatial point distribution, which has important application value in spatial analysis.

The above table shows the average nearest neighbor index of forest villages in southwest China (Table 3). The p-value is less than 0.01, indicating that it passes the 1% significance level test, and the average closest neighbor index value is 0.341991, which is less than one, indicating that the forest villages in southwest China exhibit significant agglomeration at the third-level watershed scale.

The third-level watersheds in the southwest region are mainly grouped under the Yangtze River Basin, the Southwest Rivers Basin, and the Northwest River Basin, from which rivers are derived at various levels. In Sichuan and Chongqing, the mild climate and well-developed tributary systems have resulted in a large number of forest villages that exhibit clear aggregation characteristics, while Guizhou and Yunnan have a relatively even distribution of tributaries, so there is not a strong aggregation of forest villages. Due to the great altitudinal differences and climatic variations, the Tibetan Plateau has a very small number of forest villages and is concentrated in areas near the Brahmaputra watershed with sufficient water vapor and vegetation.

As shown in Fig. 3, the center of gravity offset for each batch of forest villages was determined using spatial statistics, and a Voronoi Diagram was then made to represent the distribution of forested countryside in the Southwest as a whole. According to the findings, there are two single-center high-density core areas, one double-center high-density core area, four single-center sub-density core areas, and three single-center low-density areas spread over the first batch of forest villages. The overall distribution of the first batch of forest villages is uneven, showing a distribution pattern of “dense in the east and sparse in the west”. The distribution of forest villages in the second batch shows two single-center high-density cores, one double-center core high-density area, three single-center core sub-density areas, and one single-center core low-density area. In contrast to the more regional features of the first batch, the second batch’s overall distribution of forest settlements is uneven, and the degree of agglomeration is progressively growing. Overall, the distribution of the two groups of forest villages exhibits the traits of “high-density core aggregation, high-density continuous distribution,” which are unevenly distributed in the southwest with distinct regional variations and an apparent aggregation trend.

As shown in the figure, the high-density core areas of the two batches of forest villages are gradually strengthened and differentiation is gradually obvious, and finally together they present four single-center core areas, all of which have kernel density values of more than 33 forest villages/km2. Two of the high-density regions are beneath the Qionglai Mountains, and their distribution finally takes the form of a belt, extending from the center to the periphery. These two cores are in the Zuojiang and Yujiang mainstream watersheds of the Minjiang River watershed, and the two cores are close to each other, both located at the junction of the upper and lower watersheds of the Guangyuan- Zhaohua in Jialing River watershed. Another core area is located at the junction of the Tuo River watershed, the Fuling River watershed, the Qiu River watershed, and the Yibin-Yichang Mainstream watershed of the Yangtze River, which belong to three second-level watersheds: the Min River watershed, the Jialing River watershed, and the Yangtze River Mainstream watershed. The remaining core area is located within the upper Sinan region of the Wu River watershed. In addition to the four high-density core areas, forest villages are densely distributed in patches throughout the western Sichuan plain and the Yunnan-Guizhou plateau, and three sub-density core areas have been formed in the lower Shigu area of the Yalong River watershed in Yunnan province, the lower Bijiangkou area of the Lantsang watershed and the Nampanjiang River watershed, but they are limited in scope and do not lead to large-scale development. On the other hand, subtense cores were formed in a very small part of both the Western Sichuan Plateau and the Tibetan Plateau, located in the Dadu River Basin and the Yarlung Tsangpo River Lazhi to Paixiang Basin, respectively, but with limited diffusion and only small aggregations. Combined with the spacial statistics (Fig. 3d), it can be seen that the distribution of forest villages is gradually shifting toward the northeast, but the change is extremely small, and its center is always in the Yangtze River Basin. A slight shift in the center like this could be caused by more settlements in the northeastern area of the second batch of forest villages. Combined with the Voronoi diagram (Fig. 3e), it can also be found that forest villages are most densely distributed in the lower part of the Tuo River watershed, Qingyi-Min River watershed, Fuljiang River watershed, and Qijiang River watershed in the northeast, and there are two other densely distributed areas in the eastern part of the southwestern region, namely the Yibin-Yichang section of the Yangtze River mainstem watershed and the lower part of the Sinan section of the Wujiang River watershed.

Influencing factors of forest village distributions

Natural factor

-

(1)

Elevation

The explanatory power of elevation is the second highest among all the influencing factors, reaching 56.86%. The superimposition of elevation and the distribution of forested villages in the Southwest region shows a strong positional relationship between forested village distribution and elevation (Fig. 4).

The relationship between forested countryside and elevation can be visualized more clearly by counting forested countryside at different elevations in zones and drawing histograms. As can be seen from the figure, the number of forest villages increases and then decreases with increasing altitude, with the peak occurring between the elevation of 400—500 m, with a total of 117 forest villages. While there are 116 forest villages in areas of 300–400 m at similar altitudes, the total number of villages in these two elevation ranges is 233 (20.44%). In the region of 500–2900 m, although there are fluctuations in the number of villages, the overall trend remains downward until a small peak occurs at 3000 m, and once again declines with increasing elevation. The total number of forested villages in areas below 3,000 m is 1098, accounting for 96.32% of the total number of forested villages in the southwestern region. Because of the harsh climate, there are fewer and fewer forest villages in the highlands as the altitude rises. In fact, most of the Tibetan Plateau has no forested settlements at all. However, in the river basins of southern Tibet and the area downstream of Pai Township along the Yarlung Zangbo River, there are fewer forest villages that are clustered along the river valleys, totaling only 27, accounting for 2.37% of the total. In general, forest villages are typically found in low-elevation plains, hills, or mountainous river valleys that are well-watered and well-vegetated.

-

(2)

Slope and direction of the slope

The explanatory power of slope is 2.10%, and based on the plotted histograms, it can be seen that amount of forest villages decrease gradually with the increase of terrain slope, showing a clear inverse proportional function trend. Slope direction has the lowest explanatory power of 0.79%, so the influence of slope orientation on the distribution of forest countryside is not significant, but still relevant. The total number of villages distributed on the sunny and semi-sunny slopes is 577, while the total number of villages on the shady and semi-shady slopes is 563, which is evenly distributed (Fig. 5).

Combining slope and slope direction, it can be found that the distribution of forest villages is in plain areas with less undulation or in low-elevation hilly areas. However, the villages do not clearly favor any particular slope direction, most likely because in flatter terrain, slope direction is less likely to obstruct sunlight exposure and has less of an effect on the growth of vegetation (Fig. 6 and Table 4).

-

(3)

Annual Average Temperature

The explanatory power of the annual mean temperature is 48.09%. A histogram of the average temperature versus the number of villages for the last 5 years was plotted based on the superposition of the monthly average temperature in Southwest China for the 5 years from 2018 to 2022 (Fig. 7). As can be seen from the figure, the number of forest villages increases and then decreases with increasing temperatures, showing a clear inverted “V” distribution. The peak of the histogram is located in the region of 16 ℃ and contains 251 forest villages, and at the left of the peak, there are a total of 475 forest villages, accounting for 41.67%. On the right side of the peak, there are 665 forest villages, accounting for 58.33% of the total, while the number of forest villages decreases sharply in areas where the average temperature is 18 ℃ or higher. It can be seen that forest villages choose moderate climates, yet they may not always prefer warmer climates.

-

(4)

Annual Average Precipitation

The explanatory power of average annual precipitation is 49.37%, which is the fourth highest among all the influencing factors and has a significant impact on the distribution of forest villages (Fig. 8). The big trend is that the number of villages increases and then decreases as the average annual rainfall increases. However, a closer examination of the smaller trends reveals a narrower “M” shape in the distribution of forest communities. The peak of the entire histogram is at 108 mm of precipitation, which contains 44 forest villages, while at the right of the peak, there are three smaller peak segments, two of which are in the region of 113 mm and 119 mm of precipitation, each containing 34 forest villages, and another smaller peak at 129 mm of precipitation, containing 15 forest villages. In general, on the left side of the peak, there are 950 forest villages, accounting for 83.33% of the total, while on the right side of the peak, there are 190 forest villages, accounting for 16.67%. These lead to the pattern that “forested villages tend to be located in areas of high rainfall and show multiple clusters”.

-

(5)

Road network buffer

The explanatory power of road network density is 27.06%, which is the basic index to evaluate the scale of regional road development and the degree of road network development. Through the superposition analysis (Fig. 9), it can be seen that the road system in the whole southwest region is not developed. Combined with the distribution of the road network, it can be also found that the roads in the southwest region are dominated by provincial highways and national highways. The developed highway network in Southwest China is mainly concentrated in the western part of the Central Sichuan Plain and the southeastern part of the peripheral areas of the core cities, while the development of highways and railroads in the rest of the region is somewhat limited due to the complex and varied natural environments.

Through Arc GIS 10.8, the transportation system in the southwest is cropped out, including important transportation routes such as provincial highways, national highways, high speeds, and railroads (Figs. 10 and 11). As can be seen from the figure, the major transportation routes at all levels are concentrated in the eastern part of Southwest China, which includes the plain areas of the Yalong Jiang watershed, Min Jialing watershed, Yangtze River Main Streams watershed, Wujiang River watershed, Dongting Lake watershed, Xijiang River watershed, and Yuanjiang-Honghe River watershed. These areas tend to have urban agglomerations, flatter terrain, better economic development, and better infrastructure. The farther west you travel, the more isolated and sparsely populated the high mountain valleys and plateau regions become. The road system comprises mostly of national and provincial highways and a tiny number of railroads, and infrastructure development has been sluggish due to restricted economic development brought about by natural limits. A buffer analysis of the roads shows that there are 691,239,128 and 45 forest villages distributed in a directrix distance of 5 km, 5–10 km, 10–15 km, and 15–20 km from the road (Table 5). A total of 1103 forest villages (96.75%) are within the 20 km buffer zone of roads at all levels. This shows that there is a great relationship between forest villages and the distribution of road systems. The number of forest villages within the 20 km buffer zone of open road systems, such as Chinese highways and provincial highways, is 608 and 962, respectively, indicating that open road systems are more closely linked to the population.

-

(6)

River network buffer

The explanatory power of river network density is 5.14%, which has a certain influence on the spatial distribution of rural areas (Fig. 12).

When the tributaries of the third-level rivers are added to the calculation of the buffer zone, there are 1098 villages within all the buffer zones, accounting for 96.32% of the total number of villages, of which 499 villages are distributed within the 5 km buffer zone, 312 villages are distributed within the 5–10 km buffer zone, 208 villages are distributed within the 10–15 km buffer zone, and 79 villages are distributed within the 15–20 km buffer zone (Fig. 13). It can be seen that the largest number of villages is found within 5 km, after which it starts to decrease gradually, while the distribution of villages is rare when the straight-line distance from the river reaches more than 15 km. Comparing the results of buffer analysis of the fifth-level rivers and the third-level rivers, it can be seen that the distribution of forest villages does not depend on large rivers. There are only 383 villages within the 20 km buffer zone of the third-level rivers, while there are 715 villages within the 20 km buffer zone of their major and minor tributaries (the fourth-level and fifth-level rivers), which account for 62.72% of all forest villages (Table 6).

-

(7)

NDVI

NDVI values ranged from − 0.1 to 1.0, with positive values indicating an increasing amount of green vegetation, while negative values close to zero and decreasing indicate the absence of vegetation features such as rocks, soil surface, water, air, ice, and clouds, etc., with strong seasonal variations, therefore the annual average NDVI was chosen for the statistics13,14.

NDVI shows a strong positive correlation with precipitation and temperature, and this feature is especially obvious at high altitudes, so the distribution map of NDVI is similar to the distribution of temperature and precipitation15,16. The NDVI distribution map in the southwest is dark green, while areas with lower temperatures and less precipitation are lighter green. Because of its extreme aftereffects, most high-altitude areas in the west even display a yellow or dark red color, indicating very little to almost no vegetation cover (Fig. 14). Overlay analysis and histograms based on NDVI and the distribution of forested villages in the Southwest show that the number of forested villages increases with increasing NDVI values. When the value of NDVI reaches 0.9, the number of forest villages reaches 138; and it can be found that after the NDVI reaches 0.75, the distribution of the number of forest villages shows an up and down pattern, and in the region of the value of 0.8, there are two peaks, one large and one small, which are 48 and 76 respectively. The mean value of NDVI in the southwest region is 0.79, and there are 713 forest villages, accounting for 62.54% of the total on the left side of the mean value, which shows that the forest villages tend to be distributed in the high-value areas with richer vegetation, including the second-level watersheds, such as Jialingjiang River watershed, the Hanjiang River watershed, the mainstream of the Yangtze River, the main stream of the Yellow River, the Wujiang River watershed, the Dongting Lake watershed, the Xijiang River watershed, the Yuanjiang-Red River watershed, and most areas of the Yalong River, Lantsang, and Nu River watersheds. In contrast, there are only a relatively small amount of forest villages sporadically distributed in the higher elevations where NDVI is lower.

Social indices

-

(1)

Population density

In the later stages of rural settlement (RS) development, social factors play an important role in reshaping the internal structure of RS, and indicators such as population density and road density play an important synergistic role17. Therefore, with an explanatory power of 63.92%, the highest of all the contributing factors, population density is at the top of the list. Population density is the number of people per unit of land area, and the distribution of population density in China is extremely uneven, with densely populated areas along the eastern coast and sparsely populated areas in the western highlands17. Similar patterns can be seen in the distribution of population density in the southwestern region; the plateau of the western areas is sparsely populated, while the highest densities are concentrated in the southeast’s plains and hilly regions or the relatively developed low-elevation mountainous areas. Population density distribution is based on city distribution; high-density centers are found in the center of each city and are correlated with the level of development of individual cities. In the western Sichuan plains, these centers radiate outward to encompass a wide range of urban agglomerations with the highest density of the core (Fig. 15).

In the study area, the highest population density of forest villages is 2686 people/km2, and to visualize the relationship between population density and forest villages, a histogram was plotted based on the distribution of population density in forest villages in the Southwest region. As shown in the figure, the number of forest villages increases and then decreases with the increase in population density, and its highest value is within the range of 100–200 people/km2, with 299 forest villages distributed. The inflection point appears on the left side of the histogram, and the number of forest villages gradually decreases as population density increases on the right side of the inflection point. The mean value of population density is 268.62 persons/km2, and the peak number of forest villages appears in the area lower than the mean value, which shows that forest villages tend to be distributed in areas with lower population density.

-

(2)

GDP density

The histogram indicates a typical inverse proportional downward trend, with the number of forest settlements steadily declining as the GDP density rises (Fig. 6). The peak of GDP density is in the area of 0–5 million yuan/km2 on the left side of the histogram, and a total of 391 forest villages are distributed in this area. There are 57, 569 and 448 villages distributed in areas with GDP density of less than 100, 100–1000, 1000–5000 × 104 yuan/km2, while there are a total of 1047 forest villages within the region of GDP density of 1–50 × 104 yuan/km2, which accounts for 91.84% of the total number. In contrast, only a few forest villages exist around cities with high GDP densities, only 66 of them (Fig. 16).

It is evident that the great majority of forest villages are found in underdeveloped regions with a thriving economy. The majority of the third-level watersheds in the eastern and southern regions of Southwest China are included in these areas, such as the Yangtze River mainstem watershed, the Wujiang River watershed, the Dongting Lake watershed, the Xijiang River watershed, the Yuanjiang-Honghe River watershed, as well as the southern parts of the Jialing River watershed, the Minjiang River watershed, the Yalong River watershed, the Lantsang watershed, and the Nujiang River watershed.

The optimal geodetector result

-

(1)

Single-factor detection

Using Geodetector, the data of each influencing factor was discretized using five methods respectively, and the optimal q-value was filtered out from them, and finally, the calculation results of the 10 types of influencing factors were sorted. The results are shown in the table (Fig. 17). The p-value of each influence factor in the measurements was less than 0.01, which passed the test of significance. As can be seen from the table, the factors influencing the distribution of forested villages are: population density > average land GDP > elevation > average annual rainfall > average annual temperature > road network density > NDVI > river network density > slope > slope direction (Table 7).

-

(2)

Detection of factor interaction

The interaction detection was conducted on the selected 10 influencing factors. The results (Fig. 18) show that among the driving forces under the two-factor interaction, the interaction between X9 ∩ X1 has the strongest driving force, which is consistent with the single-factor detection results. Meanwhile, the interactions between X9 ∩ X10 and any other factors are all enhancing. Additionally, the interactions between X4 ∩ X1 (q = 0.6332) and X5 ∩ X1 (q = 0.6153) also have relatively strong driving forces. However, the interaction between (X3) ∩ X2 (q = 0.0334) is the weakest, which is consistent with the single-factor detection results where the q values of X2 ∩ X3 are the lowest.

Discussion

Characteristics of national forest countryside distribution in southwest China

China boasts a large land area with a three-step topography, particularly in the southwest of the nation, where the intricate topography also results in a wide range of weather conditions. China is also in a period of rapid development, and the level of construction varies greatly from region to region, which has a very different impact on the development of the villages around them18. The closer the village is to the city, the more it is influenced by the city, and the more remote it is, the more likely it is that there will be a lack of public resources, which will lead to deficiencies in all aspects of infrastructure19,20. Overall, the national forest villages in Southwest China can well reflect the above point of view. Because of the region’s unique topography, only the eastern plains and hilly regions have experienced greater development, giving rise to urban agglomerations with strong economic growth and well-developed transportation networks. Therefore, the distribution of national forest villages in Southwest China also shows the overall trend of “dense in the east and sparse in the west”, and in the second-level watershed perspective, there is a clear aggregation of distribution, mainly concentrated in the Jialing River, Minjiang River, Wujiang River, Dongting Lake, and Xijiang River watersheds.

Spatially, the national forest villages in the southwest region have formed a concentrated and continuous distribution pattern of “sparse in the west and dense in the east, with four high-density cores as the center of radial diffusion to the surrounding area”. The formation of this distribution pattern can also fully reflect the strong influence of social development factors on rural development and is also conducive to exploring patterns of rural conservation and development.

Influencing factors

The distribution of national forest villages in the Southwest results from many interrelated causes, which can be roughly divided into natural factors and socio-economic conditions, and In addition, policy orientation also has a certain influence on its distribution 19.

Natural factors

The most significant of the natural influences is the altitude factor, as well as the climatic factor, which is closely related to altitude. Among the many natural factors, altitude, temperature, and rainfall can directly affect the environment in which vegetation grows, and therefore have an intuitive impact on the distribution of forest villages.This is similar to the research conclusions drawn by Zheng Qunming21, Tang Minggui22, and others.The topography of the southwest region is complex, including the southern Tibetan Plateau, the Hengduan Mountains, the Sichuan Basin, and the Yunnan-Kweichow Plateau, with a variety of landforms such as plateaus, mountains, hills, basins, and plains. The large altitudinal and geomorphologic differences in the region have also led to variable climatic characteristics of the Southwest China region, including marine climate, highland monsoon climate, subtropical highland monsoon climate, and the unique highland climate of the Tibetan Plateau, and other types of climates. The distribution of forest villages is greatly influenced by these factors, with the majority of villages located in the plain and hilly eastern basin, which has a pleasant and humid environment. However, despite the mild climate, the southern region of the country has fewer total forest villages than the eastern region due to the region’s predominantly steep and highland terrain. In the western plateau region, a small number of forest villages show a clear tendency to converge and are concentrated in the Southern Tibet Rivers watershed, as well as in the Paixiangxia section of the Brahmaputra watershed. This region has a warm and humid river valley climate due to the convergence of the rivers and the low elevation, which forms a water vapor channel from the southern slopes of the Himalayas to the north23.

The explanatory power of road network density, NDVI, and river network density was similar, with slope and slope direction having the lowest explanatory power. The reason for this is that the river density, NDVI, slope, slope orientation, and road density are all influenced by topography and climate. Among them, the high explanatory power of the road network density is explained by the strong influence of urban development (possibly in a similar way to other socio-economic influences), and the integrity of the transportation system can directly affect the mobility of all types of goods between village-village and village-city. Greater differences in the growth of regional road construction in China have resulted from the uneven economic development of China’s many regions, as well as from poor infrastructure in some rural areas and a lack of investment in public resources24. Among them, the western region, especially the western edge of the mountainous areas and plateau regions due to the traffic flow is not large, the economic level is not high and other reasons, the road construction is slower, which in turn directly affects the degree of development of the village. In addition, the reason for the relatively small explanatory power of river density may be related to the scale of the river. According to previous studies, villages are distinctly hydrophilic, and the high availability of water sources can promote human agglomeration25. However, the study shows that large second-level and third-level rivers have a limited impact on villages, and although most villages are still concentrated in the western Sichuan plains, where there is a high density of rivers, no clear tendency towards clustering is seen. It is hypothesized that they may be more closely associated with smaller, unrecorded tributaries, while maintaining a distance from the larger main streams, thus ensuring that villages benefit from the rivers while avoiding the effects of disasters26.

NDVI, on the other hand, is strongly influenced by climate, showing different temperature/precipitation correlations in the dry and wet seasons, and a significant positive correlation in the highlands. According to the study, most of the villages are located in areas with high NDVI values, and at the same time, these areas almost coincide with climatically favorable areas, which is consistent with the strong link between NDVI and climate, where a more favorable climate nourishes the growth of vegetation, and a better ecological condition provides a good habitable condition for human beings.

Socio-economic conditions

Among the 10 selected influencing factors, socio-economic factors including population density and GDP density have the most significant influence on the distribution of forest villages. Since forest villages, as an artificially selected type of village, are significantly influenced by human promotion, and the closer they are to the city, the more advantageous the villages are in terms of resource allocation. As transitional village-urban settlements, they enjoy the associated benefits of urban development and planning, such as upgrading village infrastructure and ecological restoration and protection. Based on the central place theory proposed by W. Christaller and A.Lösch, the basic function of the city is to provide goods and services to the surrounding area, and it is located in the most critical position on the transportation network in an area that offers a very wide range of goods and services27. Cities and towns serve as important administrative, cultural, and service centers for the countryside; while the countryside complements the productive, cultural, and social potential, and thus the rural areas of the countryside may bear a part of the important responsibility for ecological protection28. Therefore, in areas close to cities, the distribution of forest villages will be strongly influenced by socio-economic factors, and ultimately show the distribution of “taking the city as the high-density core, and radially spreading down in all directions”. However, although the density cores of the distribution of forest villages are radially dispersed around the cities, their clusters are located in areas that are at a certain distance from the city but enjoy the joint benefits of urban development29.

Policy orientation

In contrast to previous research findings, this study reveals a significant positive correlation between socioeconomic factors and the spatial distribution of forest villages. This discrepancy may stem from information barriers in policy transmission and the Matthew effect caused by uneven development: Firstly, as a human-selected special settlement type, forest villages demonstrate amplified influence of socioeconomic conditions (e.g., local governments’ application enthusiasm and funding capabilities) on selection outcomes during the initial evaluation stages with limited samples. Subjective factors like expert preferences and evaluation criteria tend to disproportionately favor regions with stronger economic foundations. Secondly, the hierarchical attenuation effect in policy information dissemination enables developed regions to access evaluation policies earlier and optimize application materials, while underdeveloped villages often miss application windows due to information delays. This policy information gap, when combined with insufficient sample sizes, further reinforces the artificial association between economic factors and selection outcomes30.

Advantages and limitations

This study examines the spatial distribution characteristics of Forest Villages within China’s Southwest region, utilizing natural factors and socioeconomic indicators. Analysis from a macro perspective reveals the substantive influence of various factors on this distribution. Notably diverging from prior findings, economic and demographic factors exhibit a significant impact on village distribution. This phenomenon might be directly attributable to the criteria established by the National Forest Village Evaluation Index and the overarching construction goals of Forest Villages, namely “implementing rural revitalization and building beautiful villages.”

Furthermore, Forest Villages represent the outcome of a selection process. During the initial phase with limited sample sizes, the potential for human bias in this selection is relatively pronounced; discrepancies in local policy implementation could also contribute. Consequently, this study possesses inherent limitations.

While macro-level analysis provides valuable strategic guidance and conservation recommendations for Forest Village development in Southwest China, it fails to address specific construction and sustainable development challenges at finer scales. A more nuanced approach, involving the expansion and stratification of influencing factor screening coupled with the isolation of dominant variables, could yield more comprehensive analytical outcomes.

Future research should prioritize investigating Forest Villages at smaller scales. Such focused inquiry would prove instrumental in informing targeted village construction, development strategies, and conservation efforts.

Conclusion

The distribution characteristics of the first and second batches of national forest villages in Southwest China and their relationships with different influencing factors were quantitatively and qualitatively analyzed through spatial analysis, Geodetector, and frequency analysis. The results of this analysis were as follows.

-

(1)

A centered and continuous distribution pattern of “sparse in the west and dense in the east, with four high-density cores as the center spreading radially to the surrounding areas” is generally seen in the distribution of national forest communities in Southwest China. However, due to the great differences in topography and climate in southwest China, the four high-density cores are all located in basins, plains, and hills, including the Jialingjiang, Minjiang, Wujiang, Dongting Lake, and Xijiang river watersheds, and show a clear aggregated distribution within the basin cluster. The HH-type watersheds together form the largest and only HH-type watershed group in the southwest region, and two small LH-type watersheds are distributed immediately adjacent to the HH-type watershed group, while the LL-type watersheds form an extensive watershed group in the western Tibetan Plateau region.

-

(2)

Factors affecting the distribution of the National Forest countryside are complex, diverse, and coupled with each other, collectively influencing the distribution of the countryside. The most significant of these factors are socio-economic factors, including GDP density, and population density, which show the significant influence of anthropogenic disturbances on the distribution of countryside. Villages located at key positions on the transportation network and near areas that can provide a wide range of goods and services are able to access more development resources.Among the natural factors, the influence of topography and climate is the most significant, and among the remaining factors, the density of the river network and road network are strongly influenced by urban development, showing a high degree of consistency with the distribution of other social factors. The slope is influenced by the topography of the land, and the relatively gentle and low-elevation plains and hills are ideal areas for forest villages. Being close to water sources, having flat terrain, possessing a relatively good ecological environment, and enjoying moderate rainfall and heat conditions constitute the natural foundations for site selection of forest villages.NDVI, on the other hand, is strongly influenced by climate, and the distribution areas with high values are consistent with areas with relatively high temperatures and precipitation, which implies that places with a warm and humid climate have a good ecological environment and are suitable for the development of forest villages. All types of influencing factors are characterized by different degrees of common effects.

This study offers a relatively comprehensive analytical approach for the spatial distribution of forest villages. The research findings unveil the spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of forest villages in southwest China, which holds significant importance for the conservation and development of forest villages within the study area. Moreover, it provides a high reference value for establishing application criteria and relevant indicator systems for forest villages across China. Additionally, it offers certain insights for the research on spatial distribution, conservation, and development of various types of characteristic villages.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Li. J., Feng J. Research progress and prospect on the hollowing-out problem in rural China [J/OL]. Resour. Sci., 1–23 [2025–09–28].

Ding, S., Wu, L. & Ke, K. Historical review of the “No. 1 central document” on rural, agricultural and peasant issues: Current dilemmas, policy motivations and implementation outcomes. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 27(01), 1–10 (2025).

Xicheng, W. & Ping, Z. An analysis of Xi Jinping’s important expositions on rural ecological revitalization from a holistic perspective. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 23(03), 1–9 (2022).

Yang, X. Advances in quantitative research methodologies for the spatial layout of rural settlement in recent 20 years. Urban Plan. Int. 5(04), 72–80 (2020).

Marc, A. Landscape change and the urbanization process in Europe. Landsc. Urban Plan. 67(1–4), 9–26 (2004).

Medeiros, A., Fernandes, C., Goncalves, J. F. & Farinha-Marques, P. A diagnostic framework for assessing land-use change impacts on landscape pattern and character—A case-study from the Douro region, Portugal. Landsc. Urban Plan. 228, 104580 (2022).

Pacione, M. Models of urban land use structure in cities in the developed world. Geography 86(2), 97–119 (2022).

Kong, X. S., Fu, M. X., Sun, J. W. & Cui, J. X. Multi-scale differentiation characteristics and optimization zones of forest villages in China. Geogr. Res. 41(07), 2051–2064 (2022).

National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Measures for the Evaluation and Recognition of National Forest Villages (Trial Implementation). 2019.

Valjarevic, A. GIS and remote sensing methods in predicting the dissipation time of rural settlements under the influence of climate change in the Republic of Serbia. J. Urban Manag. 14, 500–511 (2025).

Zeng Jian, Xu. et al. Spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of temperature over the past century in southwest China. J. Chengdu Univ. Inf. Technol. 37(04), 412–421 (2022).

Ruoyi, C. Analysis of the seasonal variation characteristics of precipitation in southwest China. J. Nat. Sci. 8(5), 8 (2020).

Chuai, X. W., Huang, X. J., Wang, W. J. & Bao, G. NDVI, temperature and precipitation changes and their relationships with different vegetation types during 1998–2007 in Inner Mongolia, China: Changes in NDVI, temperature and precipitation in inner Mongolia. Int J Climatol. 33(7), 1696–1706 (2013).

Schnur, M. T., Xie, H. & Wang, X. Estimating root zone soil moisture at distant sites using MODIS NDVI and EVI in a semi-arid region of southwestern USA. Ecol Inform. 5(5), 400–409 (2010).

Sidi Almouctar, M. A., Wu, Y. P. & Kumar, A. Spatiotemporal analysis of vegetation cover changes around surface water based on NDVI: a case study in Korama basin, Southern Zinder, Niger. Appl. Water Sci. 11(4), 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-020-01332-x (2020).

Jin, K., Wang, F. & Li, P. Responses of vegetation cover to environmental change in large cities of China. Sustainability. 10(1), 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010270 (2018).

Yang, R., Xu, Q. & Long, H. L. Spatial distribution characteristics and optimized reconstruction analysis of China’s rural settlements during the process of rapid urbanization. J. Rural Stud. 47(Part B), 413–424 (2016).

Yansui, L., Yang, Z. & Yuheng, Li. China’s rural territorial system and the rural revitalization strategy. Acta Geogr. Sin. 74(12), 2511–2528 (2019).

Wang, C. et al. Rural settlement restructuring based on analysis of the peasant household symbiotic system at village level: A case study of Fengsi Village in Chongqing, China. J. Rural Stud. 47(Part B), 85–495 (2016).

Li, H. B. et al. Evolution and transformation mechanism of the spatial structure of rural settlements from the perspective of long-term economic and social change: A case study of the Sunan region, China. J. Rural Stud. 93, 234–243 (2022).

Qunming, Z., Tian, T. & Xiaoya, Y. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of national forest villages in China. China Ecotourism 11(03), 441–454 (2021).

Tang Minggui, Hu. et al. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of forest villages in China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 38(10), 258–266 (2022).

Li, W. T., Li, X. Y., Zhang, L. L. & Cheng, D. Climatic characteristic analysis of cloud water over the tibetan plateau. Clim. Environ. Res. 23(5), 574–586 (2018).

Li, S. S., Sun, J. W. & Hu, A. J. Construction of infrastructure multiplicity and coordinated development of china’s regional economy. Journal 23(3), 50–60 (2024).

Su, H., Wang, Y. W., Zhang, Z. & Dong, W. Characteristics and influencing factors of traditional village distribution in China. Land. 11(10), 1631 (2022).

Zhou, Y. X. & Tangjun, L. V. Research on relationship between the evolution of settlement form and the change of flood control function: A case study from Gaoyao area, Guangdong province. Geograph. Res. 33(3), 439–450 (2014).

Zhang, L. & Yu-Qi, L. U. Spatial analysis of the central place system based on accessibility. Scientia Geograph. Sinica 33(6), 649–658. https://doi.org/10.13249/j.cnki.sgs.2013.06.649 (2013).

Jaszczak, A., Vaznoniene, G., Kristianova, K. & Atkočiūnienė, V. Social and spatial relation between small towns and villages in peripheral regions: evidence from Lithuania, Poland and Slovakia. Eur. Countrys. 13(2), 242–266 (2013).

Qian, J., He, S. & Smith, D. Rural-urban interfaces and changing forms of relational and planetary rurality. J. Rural Stud. 116, 103614 (2025).

Zeng, R. X. & Yang, C. Policy cocoon: The failure of policy communication of in the information age and its solution. Chin. Public Adm. 9, 132–141 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the 2024 Southwestern Forestry University Education Science Research Projects [grand numbers YB202407], the Yunnan Provincial Education Department Scientific Research Fund [grand numbers 2024Y588], and the Professional Degree Graduate Students Teaching Case Library Construction of Yunnan Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jia Liu and Yushu Gong: Conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, methodology, data curation, funding acquisition. Changle Ma: Conceptualization, validation, Writing-Review& Editing, Funding acquisiton, Supervision, Project administration. Lixing Yang: software, formal analysis, investigation. Lijuan Wang: software, writing—review and editing. Qing Gui: resources, data curation. Lixue Cheng: formal analysis. Rongmei Zhang: writing—review and editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Gong, Y., Ma, C. et al. A study on the spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of forest villages in southwest China based on OPGD. Sci Rep 15, 41336 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25234-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25234-7