Abstract

We report a left upper first molar of a multituberculate mammal, from the Upper Cretaceous La Colonia Formation, Chubut Province, Argentina, which is here assigned to Notopolytheles joelis gen. et sp. nov. (Cimolodonta,?Neoplagiaulacidae). Multituberculates have been previously reported from Gondwanan land masses, but to date, only records from Australia, Madagascar, and India have been taxonomically undisputed. In South America, all previous assignments were debated or later referred to Gondwanatheria. These records include isolated molars attributed to Ferugliotheriidae and Argentodites coloniensis, only known from a plagiaulacoid premolar and originally assigned to the ?Cimolodonta. Since no molar with definitive multituberculate features could ever be found in the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, A. coloniensis was considered a junior synonym of the ferugliotheriid Ferugliotherium windhauseni. Notopolytheles joelis gen. et sp. nov. displays a typical multituberculate molar configuration of three rows of tetrahedral cups, with a cusp formula of 7B:8M:4L similar to Neoplagiaulacidae. The lower position of the buccal cusp row supported by a single large labial root suggest a high level of endemism. This finding provides strong and renewed support for the hypothesis that ferugliotheriids lack a plagiaulacoid p4 and that Argentodites coloniensis is indeed a multituberculate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multituberculata is a monophyletic group of omnivorous and herbivorous mammals that lived during the Mesozoic and early Cenozoic, ranging from the Middle Jurassic1 to the late Eocene2. They occur in a wide range of facies and depositional settings, reflecting their broad environmental distribution (from forested to semiarid and desert habitats), and exhibit arboreal3, cursorial, and fossorial adaptations4,5. Multituberculates had a wide geographic distribution, with a particularly diverse and well-documented fossil record in Laurasia2. Their record in Gondwanan landmasses is less varied, more fragmentary, and a subject of debate. They were reported from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar6, the Early Cretaceous of Morocco in Africa7,8, the Lower–Middle Jurassic of India9, and the late Early Cretaceous of Australia10,11. In South America, the presence of multituberculates has been widely debated12,13,14,15, in part due to the recognition of Gondwanatheria, a group of allotherian mammals found at Cretaceous and Paleogene levels from Patagonia16,17,18, Peru19, West Antarctica20, Madagascar21,22, India23, and with doubts in Africa24.

The phylogenetic relationships of gondwanatherians have been interpreted in different ways: they have been considered either as a southern radiation of multituberculates25, part of an unresolved polytomy with them14, or as their sister taxon within Allotheria26; alternatively, they have been proposed as part of the mammalian stem within the Euharamiyida/Eleutherodontidae clade27 or classified as Mammalia incertae sedis16,28. The Ferugliotheriidae, known exclusively from isolated dental elements, present significant taxonomic challenges within this group15. Before being interpreted as gondwanatherian, Ferugliotherium windhauseni from the Upper Cretaceous Los Alamitos Formation in Patagonia, Argentina29, was initially regarded as a multituberculate and tentatively assigned to Plagiaulacoidea12. Although Ferugliotherium is based on isolated brachyodont molariforms, a fragmentary dentary with a plagiaulacoid p4 was tentatively attributed to this genus30. Additionally, Argentodites coloniensis, which is based on an isolated plagiaulacoid p4 from the Upper Cretaceous La Colonia Formation in Patagonia, was described as a possible cimolodontan multituberculate14 but was later considered a junior synonym of Ferugliotherium windhauseni15. This reinterpretation, which effectively assigns A. coloniensis to Ferugliotheriidae, has fueled ongoing debate over whether multituberculates were truly present in South America. This association was based on the absence of molariforms with the cusp alignment pattern characteristic of Multituberculata and the high diversity of ferugliotheriid molariforms from the Los Alamitos and Allen formations15. As a result, the hypothesis that all plagiaulacoid teeth should belong to ferugliotheriids was maintained, even though no dentaries with both molariforms and a plagiaulacoid premolar were confirmed.

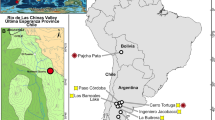

Here, we report the first evidence of a right upper molar unequivocally assignable to the Multituberculata, coming from the Late Cretaceous in Chubut Province in the Argentinian Patagonia (Fig. 1). We argue that this evidence solves a decades-long debate in South American paleontology: it is not a question of whether there were gondwanatherians or multituberculates in the Late Cretaceous of South America but rather that representatives of both groups coexisted.

Locality and stratigraphic occurrence of Notopolytheles joelis gen. and sp. nov. (a-c) Maps in different scales indicating the locality of the finding. (c) Base map data modified by the authors: © Google Earth, Image © Landsat / Copernicus. Elevation 30 km. (d) Generalized stratigraphic section of the La Colonia Formation with the three facies associations in different green tones.

Results

Systematic paleontology

Mammalia Linnaeus, 1758.

Multituberculata Cope, 1884.

Cimolodonta McKenna, 1975.

?Neoplagiaulacidae Ameghino, 1890.

Notopolytheles joelis gen. and sp. nov. (Fig. 2) urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:7FA4BA86-85CC-4D93-9C67-B9D66426EEFE

Left M1 of Notopolytheles joelis gen. and sp. nov. in different views. (a) occlusal, (b) radicular, (c) labial, (d) lingual, (e) mesial, (f) distal. The cusps rows are identified as lingual (L), medial (M), and buccal or labial (B), and each cusp is numbered from mesial to distal. Other abbreviations: dl.r: distolingual root, la.r: labial root, m.c.: mesial crest of lingual row, ml.r: mesiolingual root. Scale: 1 mm.

Etymology

The genus name refers to ‘southern multituberculate’ and derives from three Greek roots: noto- (south), poly- (many), and theles (protuberance), the last two in reference to the multiple cusps characteristic of multituberculate teeth. The specific epithet joelis is named after Joel Hernán Carino, who discovered the tooth.

Type locality and horizon

Some 12 km north of Arroyo Mirasol Chico (Mirasol Chico Stream) and 9 km south of the provincial road N° 11, in the Cerro Bosta area, Chubut Province, Argentina. Geographic coordinates: 42° 58’ 09.0” S, 67° 36’ 08.2” W (Fig. 1a-c). Middle section or second facies association of the La Colonia Formation38 (Upper Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) (Fig. 1d); Alamitian South American Land-Mammal Age.

Holotype

MPEF-PV 12400, an isolated left M1.

Diagnosis

M1 cusp formula (7B:8M:4L). Notopolytheles joelis differs from ‘Plagiaulacida’ multituberculates in having an M1 third lingual row with four well-developed cusps at the same level as the middle row of cusps, plus a short mesial crest. This third row of cusps is absent in Paulchoffatiidae, whereas it is present as an incipient posterolingual ridge in Allodontidae and Plagiaulacidae. Differs from all other Cimolodonta, especially Neoplagiaulacidae, by the unique configuration of the cusp rows, being the lingual and medial rows of the same height and higher than those of the buccal row, and by the presence of a large labial root that runs mesiodistally below the labial side of the tooth, and two smaller and rounded lingual roots on the distal and mesial sides.

Description

Specimen MPEF-PV 12400 is a well-preserved, isolated, brachydont, multicusped, three-rooted molariform tooth identifiable as a left M1 since its major axis is oriented mesiodistally and has three aligned rows of cusps, characteristic of a multituberculate mammal. It measures 2.88 mm in length and 1.38 mm in width. It is almost complete except for the distal face, which is split posterior to cusps L4, M8, and B7. In occlusal view, it is rectangular in outline and shows seven cusps in the labial (or buccal) row, eight in the middle row, and four in the lingual row (7B:8M:4L). The extension of the single labial root suggests that the missing distal portion was tiny and that most probably there were no additional cusps. The lingual side of the molar is rather straight, whereas the mesiolabial contour is more curved because of the orientation of the buccal cusps. The lingual and medial cusp rows are almost parallel. The cusps of these two rows are of similar height and exhibit greater wear than those of the buccal row, which are positioned on a lower plane of the crown, in contrast to other multituberculates, such as Paulchoffatiidae, in which the lower cusp row of the M1 is the lingual one33.

The four lingual cusps have a tetrahedral configuration with three sides (mesial, distal, and lingual), which are well defined and relatively flat. The lingual side of each cusp in this row forms the inner face of the tooth. In occlusal view, each lingual cusp has three low and rounded ridges or crests: two mesiodistally oriented, creating a continuous alignment from L1 to L4, and one transverse ridge descending labially from the cusp apex. Cusps M5-8 are mirrored relative to L1-4 and are of similar size, except for L1, which is smaller than M5. The transverse ridges of the lingual and medial cusps tend to converge but are only aligned between L2 and M6 (Fig. 2a). In terms of size, L1 < L2 < L3 < L4, and in all cases, similar wear is observed at their apices (Fig. 2a). Mesial to L1 and in the same direction as the lingual row, there is a very low and rounded mesial crest (m.c.) that seems to be delimited by two bulbous structures. This mesial crest is located at the level of the M4 cusp of the medial row (Fig. 2d). As the lingual row disappears mesially, cusps M1-3 outline the lingual margin of the tooth.

The medial row is the most extensive of the three and is formed by eight cusps (i.e., M1-8). Cusps M1-4 are similar in size, being larger and having a greater degree of apical wear than distal cusps M5-8. In the cusps of the medial row, the labial faces exhibit flat wear surfaces that descend into the valley separating them from the buccal row. The position of these wear facets appears to alternate with the apices of the cusps in the buccal row, a pattern that becomes particularly evident from M3 onwards (Fig. 2a, e, f). The transverse ridge projecting lingually on cusps M4–M8 is absent on M1–M3. The more mesial cusps are connected by low, rounded ridges, generating a slightly arched alignment between the distal part of M1 and the mesial part of M4. Distally, a roughly straight alignment is observed, from the distal part of M4 to the mesial part of M8 (Fig. 2a). The mesial face of cusp M1 projects a robust, rounded ridge, which descends distolabially and then ascends, thickening before joining cusp B1. This structure, connecting M1-B1 mesially, closes the deep valley separating the medial and buccal cusp rows (Fig. 2e).

The cusp arrangement of the buccal row includes seven cusps and forms an arc on the labial side of the tooth, from B1 to the mesial side of B4, and continues as a straight line converging to M8 between B4 and B7. This arrangement generates a larger basin between the buccal and medial cusp rows at the mesial half of the tooth. In the occlusal view, the position of the buccal cusps is transversely aligned with the valleys separating the medial row cusps, except for B1, which is aligned with the distal portion of M1, and B2, which is aligned with M2 (Fig. 2a). Cusp sizes are variable, with B2 = B3 > B4 > B1 > B5 > B6 > B7. In labial view, the cusps are separated by deep, V-shaped basins (Fig. 2c). Between cusps B1 and B2, the apex of the basin is at a higher position, and between B4, B5 and B6, the angle formed is more acute since these cusps are closer to each other (Fig. 2c). The greatest amount of wear occurs in the apical zone of B2 and continues along the ridge that descends toward the medial valley. Something similar occurs with B1, although with less pronounced wear. The remaining cusps decrease in apical wear toward B7.

In the mesial section of the tooth, an elongated basin is formed between cusps M1, M2, B1, and B2 (Fig. 2a, e). At the mesial face of the tooth, there is a rounded crest connecting cusps B1 and M1, thus closing the mesially basin, between the labial and medial cusp rows. In turn, the distal face of the crown is broken; however, the damage appears to be minimal and likely did not affect additional cusps.

The tooth has three roots (Fig. 2b). On the labial side, there is a single, robust, mesiodistally elongated root below the buccal row. Partially preserved, a second tubular root with a barely visible pulp cavity is located below the M2 and M3 cusps. A distal root appears to have been located beneath cusps L2–3, as inferred from the pulp cavity.

Discussion

Comparative dental morphology

The M1 of Notopolytheles joelis presents the typical features of multituberculate upper molars, which are covered with longitudinal rows of low cusps that vary in height, as observed in Paulchoffatiidae and Pinheirodontidae33. However, in contrast to these groups, the buccal row is the lowest, not the highest, and distally, there is a third lingual row with four cusps, which continues mesially in a short smooth ridge. The development of the third lingual cusp row brings N. joelis closer to Cimolodonta. Nevertheless, the pronounced difference in height of the buccal row distinguishes it from the typical cimolodont molar pattern, which features longitudinal rows of low cusps of subequal height.

Ferugliotherium windhauseni, a debated South American taxon previously regarded as a multituberculate, exhibits a cusp height arrangement in the lower molars that is of interest for comparison with that of N. joelis. This interpretation, however, remains tentative, as its hypodigm consists of isolated elements whose assignment to F. windhauseni may be questioned (see below). Additionally, early occlusal wear produces a flattened tooth surface that obscures height differences between cusp rows. Nonetheless, in the F. windhauseni specimen MLP-PV 88-III-28-1 —initially identified as a right m113 and later as a left m116,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34— the buccal row is higher than the lingual rows. Therefore, it could be inferred that the unknown M1 of F. windhauseni likely exhibited the opposite condition (i.e., a lower buccal row height), similar to that observed in N. joelis. This arrangement of the Patagonian forms contrasts with the lingually highest row in the upper molars of plagiaulacid multituberculates33.

In Multituberculata, the number of cusps in the M1 rows often shows intraspecific variability2, making it unreliable as the sole comparative criterion with Notopolytheles joelis. However, despite several exclusive features (e.g., differences in cusp row height and mesiodistal labial root), N. joelis shows significant similarities with members of the Cimolodonta and is assigned here to them39. Within this group, N. joelis differs from Taeniolabidoidea and Boffidae in that the lingual row disappears mesially, whereas in those groups it extends along the entire length of the tooth2,32. It also differs from the Paracimexomys group, which exhibits fewer cusps in each row and a short distobuccal ridge on M139. Furthermore, it can be distinguished from various Djadochtatherioidea35 (e.g., Catopsbaatar, Kryptobaatar, Tombaatar) by displaying a greater number of cusps in the buccal and medial rows of the M12,32,36, and from other members such as Sloanbaatar by the presence of the lingual row2. Also differs from the known M1 of Kogaionidae and Eucosmodontidae in both the greater number of cusps per row and the degree of development of the lingual row. Among Cimolodontidae, it differs, for example, from Cimolodon electus and C. foxi in having a less convex lingual cusp row. In these species, the more curved lingual row gives M1 a slightly rounded distal outline in the occlusal view37,38,39, whereas in N. joelis, it appears straight and more parallel to the median row. Closer similarities are found with the M1 of Cimolodon nitidus. However, in this taxon, the lingual cusp row presents smaller cusps and extends up to the mesial part of the tooth37,38,39, while in N. joelis, the lingual row is shorter, and the medial cusp row forms the mesiolingual surface of M1.

The most notable similarities in overall molar outline, number of cusps, and extent of the lingual cusp row are found among Neoplagiaulacidae40, and it is tentatively assigned to this family. The main similarities are particularly evident when compared with genera such as Neoplagiaulax, Mesodma, Ectypodus, or Paraectypodus2,40. Nevertheless, the unique and exclusive features of N. joelis, such as the unusually mesiodistally elongated lingual root and the lower position of the buccal cusp row, appear to suggest an early differentiation of this lineage compared to the more homogeneous M1 pattern of the Neoplagiaulacidae.

Taxonomic implications of the finding

Notopolytheles joelis confirms the presence of Multituberculata in South America and prompts a reconsideration of certain aspects of the Patagonian allotherians. The presence of multituberculates in South America has been proposed and debated on several occasions12,13,14, with one of the strongest arguments based on the fossil record of the Ferugliotheriidae, a group alternatively regarded as Multituberculata12, Gondwanatheria38, or placed in a doubtful taxonomic position either as Gondwanatheria or Multituberculata15. Discussions are due to the extremely fragmentary nature of the available materials, especially regarding those of Ferugliotherium and Argentodites.

The holotype and only known specimen of Argentodites coloniensis (MPEF-PV 604), a plagiaulacoid premolar referred to as p4, was first considered as a Multituberculata and tentatively assigned to Cimolodonta14. Additionally, a fragment of a left dentary bearing a laterally compressed, blade-like tooth (MACN-RN 975), together with other isolated plagiaulacoid premolars, was recovered from the Los Alamitos Formation. Unlike the p4 of A. coloniensis, none of these specimens were described as a new taxon or assigned directly to any taxonomic group. However, since no multituberculate-like molariform teeth had been identified in the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, all the plagiaulacoid teeth were considered to belong to Ferugliotheriidae. This included the holotype of A. coloniensis, which was interpreted as the p4 of Ferugliotherium windhauseni15. If the reasoning against considering the Patagonian plagiaulacoid p4s as indisputable Multituberculata was the absence of molars assignable to this group, this is challenged by the present description of Notopolytheles joelis. This new evidence also refutes previous claims that interpreted A. coloniensis as a junior synonym of Ferugliotherium windhauseni, supporting the validity of the former as a valid taxon. This argument opens the possibility that all the plagiaulacoid p4s from Patagonia, as well as that of A. coloniensis, may belong to Multituberculata, warranting a reassessment of the taxonomic placement and diagnosis of Ferugliotheriidae. Like Sudamericidae, Ferugliotheriidae could be characterized by the presence of four molariforms, a broad diastema preceding the incisiform, and the absence of a plagiaulacoid premolar16,31. If Ferugliotheriidae were indeed Gondwanatheria, the simplest explanation is that they never possessed plagiaulacoid premolars, and those from Patagonia should instead be attributed to multituberculates such as N. joelis.

Based on isolated elements such as those described here, it is difficult to assess the likelihood that the upper molar of Notopolytheles joelis could belong to any of the plagiaulacoid premolars or even Argentodites coloniensis itself. Several statistical analyses, which are based on length and width measurements of known p4 and M1 from various multituberculate species (Table S1), have been used to estimate the likelihood of this possible correspondence using different inference methods:

-

(1)

A linear regression analysis based on multituberculate species with complete data for p4 width and M1 length (Fig. S1) was used to infer the most likely measurements for the unknown p4 of N. joelis and the M1s of Argentodites coloniensis from Patagonia and Corriebaatar marywaltersae from the Late Cretaceous of Australia. The correlation coefficient (r = 0.93) and coefficient of determination (R² = 0.86) of the analysis suggest a strong predictive power. Residuals were symmetrically distributed around zero without clear trends, indicating no systematic bias in the fitted values. A slight increase in residual dispersion was observed for intermediate fitted values, with no extreme outliers detected (see Table S2 and Fig. S2). The residual analysis indicates that the model does not systematically overestimate or underestimate the values, although some variability is present. The inference for the Gondwanan species with missing data was based on the resulting equation of the analysis (p4 width = 0.58 + 0.31 × M1 length). The inferred values for the p4 of N. joelis and the M1 of A. coloniensis indicate that their estimated size are not identical. Although N. joelis is closer in size to the Australian C. marywaltersae, the latter falls almost entirely within the size range of Mesodma thomsoni, clearly separating it from the Patagonian forms (Fig. S3).

-

(2)

The same dataset, but with all the measurements, was used to perform two PCAs for missing data, and similar results were obtained. In the first analysis with Python, the two components captured more than 99.2% of the total variance (Fig. S4). The PC1 versus PC2 plot reveals a clear separation between A. coloniensis and N. joelis; the former occupies the upper quadrant of the morphospace, whereas the latter falls in the lower half, close to Mesodma gardfieldensis. In the second PCA performed in R, the first two components account for 99.01% of the total variance. N. joelis recovered nearest Ectypodus laytoni and Corriebaatar marywaltersae to A. coloniensis, which was separated from any other taxa in the lower quadrant (Fig. S5). Although these analyses cannot be deemed conclusive, they suggest that N. joelis and A. coloniensis are unlikely to belong to the same taxon.

Conclusion

The present description of an upper molar assignable to a multituberculate resolves longstanding uncertainties and speculations regarding the presence of this mammalian lineage in South America. The geographic and temporal distribution of Cimolodonta extends from the Early Cretaceous (Aptian–Albian) to the late Eocene in the Northern Hemisphere, and the Early Cretaceous of Australia for Corriebaatar marywaltersae10,11. As with Argentodites coloniensis, the Australian record—based solely on plagiaulacoid teeth—has also been questioned6 regarding its assignment to Multituberculata, due to the absence of known molars. In this sense, the M1 of Notopolytheles joelis supports the presence of cimolodontan multituberculates in the Cretaceous of Gondwana (Fig. S6). Furthermore, if its tentative assignment to the Neoplagiaulacidae is confirmed, it would extend the known range of the family to the Southern Hemisphere. Notopolytheles joelis displays distinctive features, such as the lower height of the buccal cusp row and the particular development of a mesiodistal root, which may suggest previously undocumented morphological adaptations in the masticatory mechanics of multituberculates. These traits may also be linked to an earlier radiation of the group in the Southern Hemisphere, potentially promoting modifications in cusp row arrangements not observed in Northern Hemisphere forms.

A second conclusion of our work is that there are no biological arguments supporting the synonymy between Argentodites coloniensis and Ferugliotherium windhauseni, both of which are regarded here as valid taxa, the former as a multituberculate and the latter as a Ferugliotheriidae. It remains impossible to establish whether Ferugliotheriidae should be attributed to Multituberculata, with which they share similarities in enamel structure, or whether they are more appropriately placed within Gondwanatheria. At least three mutually exclusive hypotheses could be considered regarding the phylogenetic placement of F. windhauseni. Depending on how its hypodigm and diagnostic features are interpreted, F. windhauseni could represent: (1) a multituberculate bearing a plagiaulacoid p4, such as that of specimen MACN-RN 975; (2) a basal gondwanatherian lacking this type of tooth and instead possessing a broad diastema between the ever-growing incisiform and molariform teeth, as observed in the more derived gondwanatherian Sudamericidae16,33; or (3) a gondwanatherian with a plagiaulacoid p4 that was subsequently lost in Paleocene forms of Sudamericidae, as posterior teeth increased in hypsodonty. The latter alternative, although less parsimonious given current evidence confirming the presence of multituberculates in Patagonia, cannot be entirely ruled out.

In summary, Notopolytheles joelis provides unambiguous evidence confirming the presence of multituberculate mammals in the Late Cretaceous of South America. The temporal co-occurrence of Multituberculata and Gondwanatheria does not appear to be fully represented across all known localities of this age. While in the Allen Formation, only ferugliotheriids have been recovered (i.e., Trapalcotherium matuastensis)41, La Colonia Formation has only yielded evidence of multituberculates (i.e., A. coloniensis and N. joelis). The presence of ferugliotheriids in La Colonia was previously reported34 based on a misattributed lower molar (MLP-PV 88-III-28-1), which comes from the Los Alamitos locality12. Given the uncertain phylogenetic position of Ferugliotheriidae—whether closer to Multituberculata or Gondwanatheria—it remains difficult to assess the potential coexistence of multituberculates and gondwanatherians at the Los Alamitos locality.

Although both groups may have exhibited ecological differentiation based on their distinct records in the mentioned localities, Patagonian multituberculates coexisted with Gondwanatheria during the Cretaceous, but pursued distinct adaptive strategies. The emergence of hypsodonty in the gondwanatherian Sudamericidae represents a clear divergence from all multituberculates and may have facilitated ecological niche differentiation between the two groups. During the Cretaceous, Gondwanatherium patagonicum from the Los Alamitos Formation, like Vintana sertichi from Madagascar21, had already evolved high-crowned teeth. This feature may have been critical for the persistence of Gondwanatheria beyond the K–Pg boundary, as evidenced in Patagonia by Sudamerica ameghinoi from the early Paleocene of Punta Peligro16 and Greniodon sylvaticus from the middle Eocene of Paso del Sapo17. By contrast, Notopolytheles joelis from La Colonia exhibited typical multituberculate traits, such as three cusp rows on the upper molar, but also unique features like a high lower buccal cusp row. Gondwanan multituberculates, in contrast to their Laurasian counterparts, appear to have been confined to the Mesozoic.

Materials and methods

The material described herein was recovered from sediment concentrate samples obtained during Rosendo Pascual’s field campaigns in the 1990s.

Nomenclatural acts

The electronic edition of this article conforms to the requirements of the amended International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN), and the new names contained herein are therefore available under that Code. This work and the nomenclatural acts it contains have been registered in ZooBank, the online registration system for the ICZN. The ZooBank LSIDs (Life Science Identifiers) can be resolved, and the associated information viewed, through any standard web browser by appending the LSID to the prefix “http://zoobank.org/” . The LSID for this publication is: [urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:7FA4BA86-85CC-4D93-9C67-B9D66426EEFE].

Institutional abbreviations

MPEF-PV, Paleontological Museum Egidio Feruglio, Trelew, Argentina. MLP-PV, División Paleontología Vertebrados, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo de La Plata, Argentina. MACN-RN, Colección Nacional de Paleovertebrados, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia”, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Tomography

Tomographic imaging of specimen MPEF-PV 12,400 was performed using a microCT system (Nikon Metrology NV; XT H 225 ST 2x) located at the Constituyentes Atomic Center, National Commission of Atomic Energy (CNEA), San Martín, Argentina. Scans were acquired at a pixel size of 2.36 μm, with an acceleration voltage of 65 kV and no additional filtration beyond the standard 1 mm beryllium (Be) window. The “Minimize Ring Artifacts” scan method was applied to enhance image quality. Image processing, segmentation, and surface model generation were done using ImageJ (version 1.54f) and Avizo 3D (2021, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Anatomical description

The molar cusp formula follows the conventions of describing multituberculate teeth2; the upper molar cusps of each row are identified by uppercase letters: B for buccal or labial cusps, M for the middle row of cusps, and L to designate cusps in the lingual row. Each cusp in each row is numbered from the mesial to the distal position. The cusp formula gives the total number of cusps in each cusp row, starting from the most buccal cusp row and separated by a colon (e.g., 4B:6M:7L).

Statistics

The measurements used in the statistical analyses (Table S1) were taken from the literature10,11,14,42,43,44,45. Regression and principal component analyses (PCAs) were performed with the ‘missMDA’ package in R46, the modules ‘Panda’, ‘sklearn.experimental’, and ‘sklearn.impute’ from the Scikit-learn library for Python47, and PAST48.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript and the supplementary information file.

References

Butler, P. M. & Hooker, J. J. New teeth of Allotherian mammals from the english Bathonian, including the earliest multituberculates. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 50, 185–207 (2005).

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., Cifelli, R. L. & Luo, Z. X. Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs: Origins, Evolution, and Structure (Columbia University, 2004).

Jenkins, F. A. & Krause, D. W. Adaptations for climbing in North American multituberculates (Mammalia). Science 220, 712–715 (1983).

Miao, D. Skull morphology of Lambdopsalis bulla (Mammalia, Multituberculata) and its implications to mammalian evolution. Contrib Geol. Univ. Wyo. Spec. Pap. 4, 1–104 (1988).

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. & Gambaryan, P. P. Postcranial anatomy and habits of Asian multituberculate mammals. Fossils Strata. 36, 1–92 (1994).

Krause, D. W. Gondwanatheria and ?Multituberculata (Mammalia) from the late cretaceous of Madagascar. Can. J. Earth Sci. 50, 324–340 (2013).

Sigogneau-Russell, D. First evidence of multituberculata (Mammalia) in the mesozoic of Africa. Neues Jahrb Geol. Palaeontol. Mon. 1991(2), 119–125 (1991).

Hahn, G. & Hahn, R. New multituberculate teeth from the early cretaceous of Morocco. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 48, 349–356 (2003).

Parmar, V., Prasad, G. V. & Kumar, D. The first multituberculate mammal from India. Naturwissenschaften 100, 515–523 (2013).

Rich, T. H. et al. An Australian multituberculate and its palaeobiogeographic implications. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 54, 1–6 (2009).

Rich, T. H. et al. Second specimen of Corriebaatar Marywaltersae from the lower cretaceous of Australia confirms its multituberculate affinities. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 67, 115–134 (2022).

Krause, D. W., Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. & Bonaparte, J. F. Ferugliotherium Bonaparte, the first known multituberculate from South America. J. Vertebr Paleontol. 12, 351–376 (1992).

Krause, D. W. Vucetichia (Gondwanatheria) is a junior synonym of Ferugliotherium (Multituberculata). J. Paleontol. 67, 321–324 (1993).

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., Ortiz-Jaureguizar, E., Vieytes, C., Pascual, R. & Goin, F. J. First? Cimolodontan multituberculate mammal from South America. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 52, 257–262 (2007).

Rougier, G. W., Martinelli, A. G. & Forasiepi, A. M. Mesozoic Mammals from South America and their Forerunners (Springer, 2021).

Pascual, R., Goin, F. J., Krause, D. W., Ortiz-Jaureguizar, E. & Carlini, A. A. The first gnathic remains of Sudamerica: implications for Gondwanathere relationships. J. Vertebr Paleontol. 19, 373–382 (1999).

Goin, F. J. et al. Persistence of a Mesozoic, non-therian mammalian lineage (Gondwanatheria) in the mid-Paleogene of patagonia. Naturwissenschaften 99, 449–463 (2012).

Goin, F. J. et al. First mesozoic mammal from chile: the southernmost record of a late cretaceous gondwanatherian. Bol. Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. (Chile). 69, 5–31 (2020).

Goin, F. J., Vieytes, E. C., Vucetich, M. G., Carlini, A. A. & Bond, M. Enigmatic mammal from the paleogene of Peru. Nat. Hist. Mus. Los Angeles Co. Sci. Ser. 40, 145–153 (2004).

Goin, F. J. et al. First gondwanatherian mammal from Antarctica. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 258, 135–144 (2006).

Krause, D. W. et al. First cranial remains of a gondwanatherian mammal reveal remarkable mosaicism. Nature 515, 512–517 (2014).

Krause, D. W. et al. Skeleton of a cretaceous mammal from Madagascar reflects long-term insularity. Nature 581, 421–427 (2020).

Prasad, G. V. R. et al. A new late cretaceous gondwanatherian mammal from central India. Proc. Ind. Natl. Sci. Acad. Part. B. 73, 17–22 (2007).

O’Connor, P. M. et al. A new mammal from the Turonian–Campanian (Upper Cretaceous) Galula Formation, Southwestern Tanzania. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 64, 65–84 (2019).

Krause, D. W. & Bonaparte, J. F. Superfamily Gondwanatherioidea: a previously unrecognized radiation of multituberculate mammals in South America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 9379–9383 (1993).

von Koenigswald, W., Goin, F. J. & Pascual, R. Hypsodonty and enamel microstructure in the paleocene gondwanatherian mammal Sudamerica ameghinoi. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 44, 263–300 (1999).

Gurovich, Y. & Beck, R. The phylogenetic affinities of the enigmatic mammalian clade Gondwanatheria. J. Mamm. Evol. 16, 25–49 (2009).

Huttenlocker, A. K. et al. Late-surviving stem mammal links the lowermost cretaceous of North America and Gondwana. Nature 558, 108–112 (2018).

Bonaparte, J. F. A new and unusual late cretaceous mammal from patagonia. J. Vertebr Paleontol. 6, 264–270 (1986).

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. & Bonaparte, J. F. Partial dentary of a multituberculate mammal from the late cretaceous of Argentina and its taxonomic implications. Rev. Mus. Argent. Cienc. Nat. B Rivadavia. 8 (1), 1–9 (1996).

Pascual, R., Goin, F. J., González, P., Ardolino, A. & Puerta, P. F. A highly derived docodont from the Patagonian late cretaceous: evolutionary implications for Gondwanan mammals. Geodiversitas 22, 395–414 (2000).

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. & Hurum, J. H. Phylogeny and systematics of multituberculate mammals. Palaeontology 44, 389–429 (2001).

Hahn, G. & Hahn, R. The dentition of plagiaulacida (Multituberculata). Geol. Palaeontol. 38, 119–159 (2004).

Pascual, R. & Ortiz-Jaureguizar, E. The Gondwanan and South American episodes in mammalian evolution. J. Mammal Evol. 14, 75–137 (2007).

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. & Hurum, J. H. Djadochtatheria – a new suborder of multituberculate mammals. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 42, 201–242 (1997).

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., Hurum, J. H. & Lopatin, A. V. Skull structure in Catopsbaatar and the zygomatic ridges in multituberculate mammals. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 50, 487–512 (2005).

Fox, R. C. Early Campanian multituberculates (Mammalia: Allotheria) from the belly river Formation, Alberta. Can. J. Earth Sci. 8, 916–938 (1971).

Eaton, J. G. Santonian (Late Cretaceous) mammals from the John Henry member of the straight cliffs Formation, Utah. J. Vertebr Paleontol. 26, 446–460 (2006).

Hunter, J. P. & Archibald, J. D. Geological Society of America Special Paper 361,. Mammals from the end of the age of dinosaurs in North Dakota and southeastern Montana, with a reappraisal of geographic differentiation among Lancian mammals. In The Hell Creek Formation and the Cretaceous–Tertiary Boundary in the Northern Great Plains: An Integrated Continental Record of the End of the Cretaceous (eds Hartman, J. H., Johnson, K. R. & Nichols, D. J.) 191–216 (2002).

Zhang, Y. Phylogenetics of Neoplagiaulacidae (Multituberculata). PhD thesis, The Ohio State University (2015).

Rougier, G. W. et al. Mammals from the Allen Formation, late Cretaceous, Argentina. Cretac. Res. 30, 223–238 (2009).

Donohue, S. L., Wilson, G. P. & Breithaupt, B. H. Latest cretaceous multituberculates of the black Butte station local fauna (Lance Formation, Southwestern Wyoming), with implications for compositional differences among mammalian local faunas of the Western interior. J. Vertebr Paleontol. 33, 677–695 (2013).

Novacek, M. & Clemens, W. A. Aspects of intrageneric variation and evolution of Mesodma (Multituberculata, Mammalia). J. Paleontol. 51, 701–717 (1977).

Archibald, J. D. A Study of Mammalia and Geology across the Cretaceous–Tertiary Boundary in Garfield County, Montana (University of California Press, 1982).

Jepsen, G. L. Paleocene faunas of the Polecat Bench Formation, Park County, Wyoming: Part I. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 83, 217–340 (1940).

Josse, J. & Husson, F. missMDA: a package for handling missing values in multivariate data analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 70, 1–31 (2016).

Kanagachidambaresan, G. R. & Bharathi, N. Learning Algorithms for Internet of Things: Applying Python Tools to Improve Data Collection Use for System PerformanceApress,. (2024).

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T. & Ryan, P. D. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4, 9 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Carino, L. Carrera Aizpitarte, L. A. Sesma Talavera, C. Torossian, P. Valtueña, and J. P. Pérez Panera for their laboratory assistance, which included sediment sieving, microvertebrate recovery, and specimen preparation. We also thank P. Puerta for providing information on localities surveyed during the 1990s field campaigns, M. Tomeo for assistance with Figure 1, and J. Leite for his advice. We particularly appreciate J. Schultz and J. D. Archibald for facilitating access to key bibliographic resources, and D. García-López, F. Tolchard, and F. D. Seoane for their valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.N.G. and F.J.G. conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. N.A.V. performed the microCT scan. J.N.G. prepared the supplementary information, all the final figures and the table. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gelfo, J.N., Goin, F.J. & Vega, N.A. First unambiguous evidence of Multituberculata from the Late Cretaceous of South America. Sci Rep 15, 41500 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25255-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25255-2