Abstract

The reliability and robustness of GaN devices continues to suffer from the influence of high dislocation densities. Our group has previously linked dislocations with current leakage paths. In this study, we investigated the localized electroluminescence (EL) signals of these leakage paths in reverse biased GaN pn-diodes grown on a sapphire substrate for their electrical and structural properties. We show that EL signal correlated leakage currents can be modeled by trap-assisted-tunneling (TAT) through segregated impurities at a dislocation. Leakage currents in devices without these leakage paths can be modeled by the Poole-Frenkel (PF) and phonon-assisted-tunneling (PAT) mechanisms. Additionally, we show that this reverse bias leakage, that has historically been attributed to specific dislocation types, cannot be attributed to a specific Burgers vector type.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

GaN is quickly becoming a competitive semiconductor for power electronics, offering high carrier mobility and high breakdown voltages. These properties have allowed for the creation of ~ 8 kV capable diodes and transistors1,2. However, these devices could only reach this performance by avoiding one of the major quality issues in GaN material; threading dislocations (TD).

Lateral devices avoid the impact of leakage at vertical TDs by conducting across horizontal electric fields. Unfortunately, the lateral electric field in off-state operation leads to surface electron trapping which can negatively impact device performance and reduce device reliability. Increasing the source-drain length can reduce the surface electric field and increase breakdown voltage, but at the cost of chip size, which is also impacted when scaling the power output of lateral devices. Larger chip sizes then lead to difficult current extraction and poor reliability3.

Vertical devices are able to scale the breakdown voltage without changing the device footprint and their vertical design has more uniform current density and electric field distribution, which allows increases power density. Vertical designs are therefore highlydesired for future device technologies. However, vertical devices cannot avoid the parasitic leakage of vertical TDs as lateral devices do, which limits the achievable defect free area of vertical devices4,5.

To develop an industry scale device with a high breakdown voltage, low Rds, and high switching power, it is essential to better understand the origin of vertical leakage currents in reverse-biased devices. Many groups have researched leakage currents in GaN devices and have shown that leakage paths at dislocations are visible in EL imaging6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. EL imaging can measure the photons that e-field accelerated carriers generate as they collide with the material they travel through. Therefore, any strongly localized current path appears in EL imaging. The difficulty is in evaluating the electrical properties of these localized leakage sources, and in determining the physical structures responsible for the leakage path.

Many of the previous groups have been forced to use unconventional methods to evaluate the electrical impact of these localized leakage sources; for example, conductive atomic force microscopy or e-beam deposited contacts in etched v-pits. These approaches leave the questions of device level relevance and statistical repeatability largely unanswered. Furthermore, most of the previous studies evaluated either the electrical leakage mechanisms or the physical structure of localized leakage sources, leaving the connection between the two unanswered.

In this study, we resolve these unanswered questions by evaluating the electrical influence of localized leakage currents for 115 diodes at the device level with standard IV curve analysis and we image the physical structures of those localized leakage sources with conventional electron microscopy techniques.

Our device fabrication choices were critical in facilitating the direct measurement of localized leakage currents. GaN pn-diodes grown on sapphire substrates were selected, as the straightforward design of pn-diodes enables direct evaluation of electrical properties while minimizing the impact of variations introduced in the design and fabrication processes. Sapphire substrates were chosen because they offer a balance between industrial production requirements, offering moderate costs, mature epitaxy procedure, large wafer diameters, and a relatively low threading dislocation density (TDD) when compare to GaN-on-silicon.

Besendorfer et al. observed that around 1 in 1000 dislocations exhibits dominant localized leakage19,20. Based on this and the typical 1 × 108 cm−2 TDD for GaN epitaxial layers grown on sapphire substrates, a device containing an average of one dominant localized leakage spot would need a diameter of 20 μm. In contrast, achieving the same localized leakage spot density per GaN-on-silicon diode would require devices as small as 6 μm in diameter. At such a small scale, the complexities of device manufacturing and measurement increase significantly. By opting for GaN-on-sapphire, we were able to fabricate high-quality pn-didoes at a size scale that allowed for comfortable execution of precise electrical measurements.

This approach allowed us to demonstrate that localized leakage sources predominantly dictated the diodes’ electrical behavior. Furthermore, we were able to identify the leakage mechanisms responsible for this localized current and establish that there is no correlation between the observed localized leakage currents and dislocation type.

Materials and methods

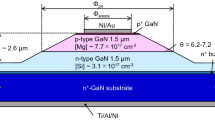

Figure 1 shows a schematic cross-sectional diagram of the 50 to 200 μm diameter circular mesa pn-diodes. These diodes were grown via metal organic vapor phase epitaxy (MOVPE) using an AIXTRON AIX2600G3-HT system to produce a 30 nm thick p-GaN layer with Mg doping of 2 × 1019 cm−3, a 500 nm thick p-GaN layer with Mg doping of 1 × 1019 cm−3, a 5 μm thick n−-GaN layer with Si doping of 4 × 1016 cm−3, a 2.4 μm thick n+-GaN layer with Si doping of 3 × 1018 cm−3, and a 2.2 μm thick uid-GaN layer on a 0.2° m-offcut \(\:\left(0001\right)\) sapphire substrate21. Semi-vertical pn-diodes were fabricated from this epitaxy, as illustrated in Fig. 1, and are described in more detail in Brusaterra et al.22.

Cross-section of the GaN-on-sapphire pn-diodes in this study. The mesa structure contains the p-GaN source and n–GaN drift zones and is surrounded by a low-voltage SiN passivation as well as a high-voltage passivation. The diodes are contacted semi-vertically through a highly doped n+-GaN layer. All layers were grown/deposited on a sapphire substrate.

After processing, reverse bias sweeps were conducted for 115 diodes of diameter 50 μm and for 5 diodes of diameters 200, 150, 100, 75, and 50 μm using a Keithley 2756 A high voltage SMU. The IV behavior of selected diodes was further measured across a temperature range from 60 °C to 200 °C in order to analyze the temperature dependence of the diodes’ current leakage mechanisms. Electroluminescence (EL) images were then taken at −300 V reverse bias for 50 diodes of interest using a Hamamatsu Phemos-1000 with InGaAs camera system to reveal the location of hot-electron emission leakage paths within the active area of the diode. The frontside metallization was then removed, allowing platinum grid structures to be deposited onto the p-GaN surface around the localized EL spots via e-beam deposition using an FEI Helios-66 0 Duel-beam focused ion beam (FIB). EL imaging was repeated from the frontside, followed by electron channeling contrast imaging (ECCI) of the area surrounding the EL spots of interest of 15 diodes using a Zeiss GenimiSEM 500. The platinum grid is visible in both EL and ECCI images, which allowed for the alignment between imaging techniques and correlation of EL spots and local dislocations.

The 15 diodes were prepared for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with a ThermoFisher Scientific Helios5 FIB system. The diodes were prepared with the AutoTEM5 software using an 800 nm target thickness, to ensure the capture of the region of interest, followed by a final sample polish at 5 kV. Subsequent TEM imaging was performed on 14 samples at 200 kV in scanning mode (STEM) at 10.5 mrad convergence with an FEI Tecnai F20. Each sample was imaged in four conditions: along the \(\:\left[1\stackrel{-}{1}00\right]\) zone axis, where all dislocations are visible, in a \(\:\left(0002\right)\) two-beam diffraction condition, where dislocations with a c-component are visible, and in the \(\:\left(11\stackrel{-}{2}0\right)\) and \(\:\left(1\stackrel{-}{1}00\right)\) diffraction conditions, where dislocations with an a- and m-component are visible. It is important to image at least four conditions when classifying dislocations as some fringe cases could otherwise be falsely classified. The samples were tilted 8–10 degrees from the zone axis to reach these two-beam conditions.

Results and discussion

Observation of EL spots in GaN-on-Sapphire pn-diodes

Similar to EL investigations of GaN material from literature, the diodes in this study showed localized EL peaks within the active area of the diodes. The EL imaging in this study was done with an InGaAs camera and primarily shows hot-electron emission at locations of heightened current density. EL imaging of 115 50 μm diodes under reverse bias has shown an average localized EL spot density of 8 × 104 cm−2 or about 3 spots per diode. Local fluctuations in dislocations density are expected and were observed in EL spot density as well, with some diodes show up to 10 spots and some showing no spots at all. Figure 2 shows the EL images of two diodes under − 300 V reverse bias. Diode A represents diodes showingdominant localized EL peaks, and diode B represents diodes showing predominantly background noise. A lack of EL signal at the perimeter of the mesa diodes, in combination with the area scaled IV measurements shown in Fig. 2c, proves that the diodes do not exhibit significant sidewall leakage. The EL intensity of Fig. 2b is scaled 30 times more than in Fig. 2a in order to distinguish the EL signal in 2b from the background noise. At this scaling, a weak localized signal is visible in diode B. This signal is likely similar to the localized signals in diode A, but present at a significantly lower intensity. Literature has shown that dislocations in GaN typically have a higher conductivity than surrounding bulk material, regardless of impurity segregation23. It is therefore likely that the localized signal in diode B corresponds with a dislocation that has little to no impurity segregation and therefore corresponds only weakly to the reverse bias leakage current. This conclusion is confirmed in the IV plots of Fig. 3.

InGaAs electroluminescence (EL) images superimposed to greyscale optical images of two 50 μm GaN pn-diodes under − 300 V reverse bias. The EL intensities are scaled differently as the signal from diode A is 30x more intense than that from diode B. Diode A represents diodes with a singular dominant localized EL signal while diode B represents diodes without a dominant localized EL signal. Both diodes show no EL signal at their perimeters. This indicates that the diodes leak through the active area and not along the sidewall. Area scaled IV measurements of diodes with differing areas, Fig. 2c, confirm this as well; though a deviation at low biases is visible. Current density is plotted as an absolute value.

Difference in leakage current behaviors

Figure 3 shows the reverse bias leakage currents for the two diode types. Diode B shows consistently increasing current across all measured temperatures, with little change in the shape of the IV curve. In comparison, diode A shows a strong increase in leakage current at biases below − 75 V and at temperatures below 140 °C. All diodes which did not show strong localized EL signals exhibited IV behavior similar to diode B, and all diodes with singular localized EL signals exhibited IV behavior similar to diode A; indicating that the mechanism of diode A’s increased leakage current is physically localized. Additionally, the localized leakage current is only dominant at high reverse biases and low temperatures, indicating that the diodes must conduct via multiple transport mechanisms.

IV plots for diodes A and B from 0 V to −300 V reverse bias over a temperature range from − 60 °C to 200 °C. Diode B shows a consistent slope across all biases and temperatures. Diode A, with a dominant EL spot, shows a strong increase in leakage current for temperatures below 140 °C and for biases below − 75 V. Current is plotted as an absolute value.

Modeling and fitting of current transport mechanisms

These transport mechanisms should also differ in their respective E-field and temperature dependencies. Table 1 shows that carrier transport mechanisms rarely share E-field and temperature dependencies24,25,26,27,28. Therefore, the transport mechanisms can be uniquely identified by examining the diodes relationship between current and E-field/temperature. This examination is best shown by scaling the IV plot axes to match the E-field dependencies to those shown in Table 1, where E-field maximum is calculated as the potential drop over depletion width. The influence of each mechanism is determined by the absence/presence of an obvious linear relationship in the range of the plotted data where that mechanism is dominant. Figure 4 shows the IV curves of diode B with axes scaled such that any current generated via phonon-assisted tunneling (PAT) will display an obvious linear relationship. It can be seen that linearity is present across all temperatures for the majority of the measured E-field.

At low E-fields, however, a deviation from linearity is seen, caused by the influence of an additional leakage mechanism. Ganichev et al. have shown that devices exhibiting PAT also exhibit this low E-field behavior, where Poole-Frenkel (PF) becomes the energetically favorable leakage mechanism24. Briefly summarized from Ganichev et al., the application of an E-field increases the potential slope of the conduction band. The probability of ionizing a charge center subjected to this sloped potential increases as the slope increases, i.e. as the E-field is increased, because the ionization barrier is decreased as the potential slope increases. Provided the barrier is sufficiently reduced, the charge carriers will be ionized from their centers to the conduction band and are then free to be swept along the conduction band to the contact. Furthermore, as the potential barrier further reduced, the barrier thickness becomes narrow enough to support tunneling. At some point, it is energetically advantageous to tunnel the carrier through the barrier rather than ionize it over the barrier, especially if the carrier’s energy is increased though phonon interaction prior to tunneling. This phonon-assisted-tunneling (PAT) then dominates at higher electric fields. In either case current is generated by transporting the charge center bound carriers to the conduction band and sweeping them along the E-field to the contact. A fit of PF leakage at low E-fields is plotted as a dashed line in Fig. 4, showing a good agreement to the measured device current.

Plot of the IV curves for diode B with the y axis scaled as the natural log of current and the x axis scaled as the square of electric field. This axes scaling will display linearity for current generated by phonon assisted tunneling (PAT). A fit of PAT for diode B at 200 °C is included as a black dotted line. Similarly, a fit for Poole-Frenkel (PF) is plotted as a dashed black line to show the presence of this additional mechanism at low electric fields.

As they are bulk leakage mechanisms, PF and PAT are also present in diodes with localized leakage. When investigating the linearity between current and E-field with respect to some additional mechanism, one must be careful to only examine the data range for which the additional transport mechanism is dominant. This range is highlighted in Fig. 5, which is scaled to ln(I/E) vs. 1/E to show linearity when trap assisted tunneling (TAT) is present. From Table 1, it can be seen that PF and PAT mechanisms are temperature dependent, whereas TAT is not. This temperature dependence causes an increasing deviation from TAT linearity with increasing temperature as more and more of the current is generated from the competing mechanisms. Because of this, the TAT linearity is best observed in the − 60 °C curve of Fig. 5, where the low thermal energy inhibits PF and PAT from contributing current.

Plot of the TAT component of the IV curves for diode A, which was isolated by subtracting the current of diode B from the current of diode A. The y axis is scaled as ln(I/E) and the x axis scaled as 1/E; this scaling will display linearity for current generated by trap assisted tunneling (TAT). Only the green highlighted region for electric fields greater than 1 × 106 V/cm is relevant when examininglinearity, as this is the region where the additional leakage mechanism is dominant. Linearity is best observed in the lowest temperate curve, as increasing temperature increases the influence from PF and PAT mechanisms, skewing the linear relationship. In black a fit of TAT for diode A at −60 °C.

While PF ionizes carriers over a potential barrier and PAT requires phonon excitement to facilitate tunneling, TAT can tunnel carriers directly through the potential barrier. TAT is therefore only expected at higher e-fields, where the potential barrier is sufficiently narrow to support this direct tunneling. This transport mechanism generates current in our devices by separating electron-hole pairs in the valance band, the hole then being swept along the E-field to the p-side contact and the electron tunneling to an acceptor trap within the band-gap. That electron then tunnels out of the trap into the conduction band, where it is swept along the E-field to the n-side contact. In our devices, the connection between TAT current and localized EL spots also implies the existence of a locally increased trap density at the location of the EL spots.

It must be noted, that TAT is not the only transport mechanism which exhibits a ln(1/En) vs. 1/E linearity. Band to band tunneling (BTBT) and Foweler-Nordheim tunneling (FNT) also share this relationship with the only differences being the exponent of E. All three mechanisms achieve good linearity at E-field ranges where increased leakage current was seen in the IV curves. While it is impossible from the IV data to distinguish TAT from BTBT or FNT mechanisms, it is valid to exclude FNT as it is a mechanism exclusively relevant in the presence of Schottky barriers and/or triangular potential wells. More work needs to be done to ultimately distinguish between BTBT and TAT; however, literature often supports the presence of localized trap states. The localized leakage seen in the EL images of these diodes is most likely due to the recombination of carriers generated via TAT.

Having isolated likely mechanisms for the leakage seen in these diodes, it becomes possible to apply analytical fitting models. Each of the models is limited to two fitting parameters, an I0 to scale the magnitude of current measured around 0 V, and a single physical parameter. The physical parameters for PF, PAT, and TAT are the Poole-Frenkel constant (βPF), tunneling time (τ1), and trap energy measured from the valance band (ET), respectively. The values obtained after fitting are a βPF value of 4.2 × 10−5 eV V−½ m−½, a τ1 value of 150 ± 4 fs, and an ET-EV value of 0.65 ± 0.2 eV. These values match decently with existing literature29,30,31. An acceptor in n-GaN with this ET value of EC−2.6 eV corresponds with gallium vacancies and associated hydrogen complexes31. It also matches decently with the EC−2.5 eV that Qwah et al. and Robertson et al. chose for their TCAD simulations of TAT at dislocations32,33. The strain field of the dislocations with leakage currents has likely attracted these point defects, heightening the local density and creating the conditions that allow TAT to occur.

IV curves of diodes A and B showing the PF + PAT fits as well as the additional TAT fit for diode A. The fits in dashed black lines are superimposed on the IV data and show good agreement. Areas of deviation arise at low currents where the SMU hit the noise floor, and at the transition from PF to PAT mechanisms around − 25 V to −75 V. Current is plotted as an absolute value.

Fitting was done by first fitting the PF and PAT models to sections of the electric field for which those mechanisms are dominant in diode B. Those fit values were then used as a baseline to which the model for TAT was added. Fitting for TAT was done for all electric field values and repeated for each temperature range independently. Figure 6 shows the modeled IV curves as dashed black lines overlaid on the raw IV data. The fits are generally in good agreement with measured data, deviating slightly at lower voltages. A transitional relationship is expected between the PF and PAT mechanisms, and more work should be done to analytically define this transition. Within the scope of this work, however, a hard transition was made, which has led the sharp change seen around − 25 V, where neither mechanism is singularly dominant. Some minimal sidewall leakage or Shockley-Reed-Hall (SRH) generation could also introduce fitting error at these lower voltages. Additionally, the fits deviate at low currents, where the measurements were influenced by the probe station’s background noise. The equations used for these analytical fitting models are written in Table 1.

Observation of a direct exponential temperature relationship

In order to maintain physically realistic fitting, the models in Table 1 calculate current analytically with as few fitting parameters as possible. However, the temperature dependence of the PAT and PF models is subverted by fitting values for each IV measurement separately, rather than fitting one value for all temperatures collectively. In this way, the temperature dependence is strongly influenced by the magnitude of the fitting parameters, rather than solely by the value of T. This approach is necessary, as the diodes exhibited a direct exponential temperature dependence.

Figure 7 shows the temperature dependence of the leakage currents in diodes A and B at a constant − 250 V reverse bias. Fits for a direct and inverse exponential current-temperature dependence are also overlaid as dashed and dotted lines, respectively. Diode B shows a direct exponential relationship across all temperatures, and diode A deviates from this relationship only for temperatures at which TAT dominates. A similar behavior was seen by Koller et al., and to the best of our knowledge remains otherwise undocumented34. This relationship is unexpected, as temperature dependent transport mechanisms typically have inverse exponential relationships, such as \(\:I\:\propto\:\text{e}\text{x}\text{p}(\frac{q{E}_{a}}{{k}_{b}T})\).

Current vs. temperature plot showing in red squares diode A and in green diamonds diode B; both taken at −250 V reverse bias. The blue circles line shows the current of TAT in diode A by subtracting current of diode B from that of diode A and exhibits an expected non-dependency on temperature. The temperature dependence of diode B is best fit by a direct exponential relationship, which deviates from the expected inverse exponential relationship found in all temperature dependent leakage mechanisms. Current is plotted as an absolute value.

A common approach to explain complex temperature relationships in Si devices is tofit multiple inverse exponential relationships for arbitrary subsections of the temperature spectrum. The decay factor of those fits then corresponds with the activationenergies of theoretical traps states involved in current leakage. This approach yields a multitude of activation energies, whose corresponding trap states dominate only for the particular temperature ranges for which their fits match the data. We agree with Koller’s assessment; without additional data on the devices’ known trap states, this method of analyzing IV curves is at best a phenomenological approximation und unfit to rigorously determine leakage mechanisms. Furthermore, for emerging materials such as GaN, where known trap states have yet to be fully understood, this fitting approach will likely yield false positive results on non-existent trap states. The temperature relationship in these diodes cannot yet be explained analytically, therefore, the temperature dependent PF and PAT parameters remain fit parameters.

An additional line is plotted, showing the result of subtracting diode A’s current from the current of diode B, which isolates the current generated by TAT from that of PF and PAT in diode A. This albeit noisy data is constant for all temperatures, an expected relationship for this TAT model. Qwah and Robertson have recently built this TAT model into their TCAD model of leakage at trap-state decorated threading dislocations in GaN diodes32,33. In order to better understand the physical structures responsible for the TAT current found in these diodes, 14 diodes similar to diode A with singular, localized leakage signals were prepared for TEM analysis.

Analysis of TEM diffraction contrast and dislocation typing

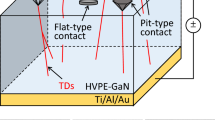

The localization for a diode with a single dominant EL spot is shown in the inset and body of Fig. 8a, as well as the ECCI image of the EL spot area. The EL spot is denoted by a red 1 μm circle surrounding the five pixels of highest EL intensity, which are also shown. A blue square surrounding this EL spot shows the 800 nm thick TEM lamella cut from this diode. Figures 8.b-e are STEM images of that lamella and highlight the EL spot area with a red square, that encloses a 1 µm2 area around the intersection of the EL spot and the p-n interface.

The lamella was analyzed by tilting the sample into different strong two-beam diffraction conditions and using the g·b = 0 disappearance condition to determine Burgers vector type. Figures 8b-e show the four imaging conditions used: along the \(\:\left[1\stackrel{-}{1}00\right]\) zone axis, in a \(\:\left(0002\right)\) two-beam condition, in a \(\:\left(1\stackrel{-}{1}00\right)\) two-beam condition, and in a \(\:\left(11\stackrel{-}{2}0\right)\) two-beam condition, as described in the experimental methods. Assuming that the GaN material only contains dislocations with a Burgers vector parallel to the a-axis, the c-axis, or a linear a + c combination, then these four images allow the dislocations to be characterized as one of these three types. It should be noted here that for the convergent beam used for the STEM analysis, and the ~ 800 nm thick samples, some dislocations will not fully disappear in the g·b = 0 condition. However, a drastic change in contrast is still observed.

Qwah and Robertson have shown that the carrier generation originates at the p-n interface of the diode32,33. Therefore, any influence on leakage must be present in the area surrounding the carrier generation origin. The Burgers vector types for all the dislocations within a micrometer cube centered at the carrier generation origin of each diode are summarized in Table 2. Each row of the table lists the number of each dislocation type found in the area of interest for each electrically isolated diode. Dislocations with a c-type or a + c-type Burgers vector have periodically been linked to device leakage in the literature; no such clear connection is observed here12,14,15,16. Among the 14 areas of interest successfully investigated, one contained no a-type, one contained no a + c-type, and ten contained no pure c-type dislocations. This dislocation distribution also matches well with a previous TEM study of electrically active dislocations in GaN35. Additionally, open-core dislocations were found outside the defined area of interest, meaning open core dislocations did not produce EL signal in these diodes.

a) ECCI image of the area around the origin of a singular localized EL signal. The inset shows the EL localization for this sample. The five pixels of highest EL intensity and a surrounding 1 μm circle depict the EL localization. The bright structures are platinum orientation marks, also visible in the inset EL image, which allowed for accurate superimposition of EL and ECCI images. b-d) Three bright field scanning transmission electron microscope images of the two-beam analysis. From the left we see: the \(\:\left[1\stackrel{-}{1}00\right]\) zone axis, the \(\:\left(0002\right)\) diffraction condition, the \(\:\left(1\stackrel{-}{1}00\right)\) diffraction condition, and the \(\:\left(11\stackrel{-}{2}0\right)\) diffraction condition. \(\:\left(0002\right)\) shows contrast for dislocations with a c-component Burgers vector while \(\:\left(11\stackrel{-}{2}0\right)\) and \(\:\left(1\stackrel{-}{1}00\right)\) each show both a- and m-components. By comparing the contrasts, the dislocation type can be evaluated. These have been overlaid here as ‘a’ for a- or ‘a + c’ for a- and c- components; as a- and m-components cannot be distinguished, only ‘a’ is assigned to the relevant components. A red box is centered around the origin of EL signal.

The absence of a dislocation type in the area of interest excludes it from being solely responsible for the TAT leakage current. Simply put, if EL signal can be generated in the absence of a specific dislocation type, that specific dislocation type can not be solely responsible for the generation of the EL signal or its associated leakage current. Table 2 contains a diode in which each of the dislocation types is absent, despite the presence of EL signal and associated leakage current, thus we conclude that a-type, a + c-type, c-type, and open-core dislocations themselves are not solely responsible for the presence of EL signal and associated leakage current. Similar results were also observed in an earlier study of AlGaN/GaN HEMTs on Si substrate36.

The Burgers vector type has often been correlated with localized leakage, because it is a singular value that describes many aspects of a dislocations physical structure. However, studies which examine the correlation of leakage current with burgers vector type often conclude that dislocation type alone is not solely responsible for leakage, and often suggest trap state accumulation as a possible cause12,16,36. Our data in Table 2 proves that dislocation type alone is not solely responsible for current leakage, and our TAT modeling suggest trap state involvement. However, our data cannot refute the claim that multiple dislocations types (c-type and a + c-type) can cause leakage current, as Diode-02 and Diode-05 both contain dislocations with a c-component to their Burgers vectors. Therefore, two theories remain possible: either dislocation type is independent of leakage current, or a dislocation with a c-component is required for leakage to occur. More study is required to determine which theory is correct. We are, however, confident that a singular Burgers vector type cannot be solely responsible for leakage at dislocations.

Conclusion

In this study we investigated leakage currents in 115 GaN-on-sapphire pn-diodes. We have shown that the measured reverse bias leakage current is comprised of bulk and localized components corresponding to PF + PAT and TAT mechanisms, respectively. Analytical models for PF and PAT leakage mechanisms fit well to the measured IV curves of diodes without dominant localized leakage currents. The inclusion of an additional analytical model for TAT provides good fitting of the IV curves for diodes with dominant localized leakage currents. A complex, direct exponential temperature dependence was found for PF and PAT models, which requires more study to understand. Despite this, EL microscopy showed that the leakage current associated with TAT in these diodes is localized to sub-micron points within the diode active area. STEM two-beam analysis of the dislocation network at 14 of these localized leakage centers shows that the Burgers vector type is not the predominant factor determining localized TAT leakage.

Our investigation has produced both an evaluation of the electrical leakage mechanisms and a physical analysis of the structures present at localized leakage sources. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first investigation which has demonstrated both of these results on the same device. Understanding the physical structures in connection with the electrical leakage mechanisms that impact GaN devices is critical to improving the electrical properties of future devices. State of the art has continually suggested that the Burgers vector, or dislocation type be the primary factor determining if a dislocation should act as a localized leakage source. Our TEM results on 14 diodes from the same sample reject this suggestion and instead indicate that the dislocation type is not the sole factor determining localized current leakage. Furthermore, the correlation of our leakage mechanism modeling with the modeling work of Quah and Robertson suggest that dislocation bound trap states cause the localized leakage in our samples. This suggests, that future GaN devices can be made more resistant and reliable by sufficiently reducing the trap state inclusion during growth.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Li, X. et al. Demonstration of > 8-kV GaN HEMTs with CMOS-Compatible manufacturing on 6-in Sapphire substrates for Medium-Voltage applications. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 71, 3989–3993 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. 7.86 kV GaN-on-GaN PN power diode with BaTiO3 for electrical field management. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 142105 (2023).

Hu, J. et al. Materials and processing issues in vertical GaN power electronics. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 78, 75–84 (2018).

Oka, T., Ina, T., Ueno, Y. & Nishii, J. Over 10 a operation with switching characteristics of 1.2 kV-class vertical GaN trench MOSFETs on a bulk GaN substrate. in 28th International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs (ISPSD) 459–462 (IEEE, Prague, Czech Republic, 2016). 459–462 (IEEE, Prague, Czech Republic, 2016). (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/ISPSD.2016.7520877

Shibata, D. et al. IEEE, San Francisco, CA, USA,. 1.7 kV/1.0 mΩcm2 normally-off vertical GaN transistor on GaN substrate with regrown p-GaN/AlGaN/GaN semipolar gate structure. in 2016 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 10.1.1–10.1.4 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2016.7838385

Hamachi, T. et al. Comprehensive analysis of current leakage at individual screw and mixed Threading dislocations in freestanding GaN substrates. Sci. Rep. 13, 2436 (2023).

Ishikawa, Y. et al. Characterization of dislocations at the emission site by emission microscopy in GaN p–n diodes. J. Mater. Sci. 58, 9221–9232 (2023).

Koller, C. et al. Trap-Related breakdown and filamentary conduction in carbon doped GaN. Phys. Status Solidi (b). 256, 1800527 (2019).

Kyle, E. C. H. et al. High-electron-mobility GaN grown on free-standing GaN templates by ammonia-based molecular beam epitaxy. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 193702 (2014).

Moroz, V. et al. The impact of defects on GaN device behavior: modeling Dislocations, Traps, and pits. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 5, P3142–P3148 (2016).

Nakano, T. et al. Screw dislocation that converts p-type GaN to n-type: microscopic study on Mg condensation and leakage current in p–n diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 012105 (2020).

Narita, T. et al. Identification of type of Threading dislocation causing reverse leakage in GaN p–n junctions after continuous forward current stress. Sci. Rep. 12, 1458 (2022).

Narita, T. et al. Reliability issues of gate oxides and p-n junctions for vertical GaN metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors (Invited). in. IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS) 1–10 (IEEE, Monterey, CA, USA, 2023). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/IRPS48203.2023.10118047

Usami, S. et al. Correlation between dislocations and leakage current of p-n diodes on a free-standing GaN substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 182106 (2018).

Usami, S. et al. Direct evidence of Mg diffusion through Threading mixed dislocations in GaN p–n diodes and its effect on reverse leakage current. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 232105 (2019).

Usami, S. et al. Correlation between nanopipes formed from screw dislocations during homoepitaxial growth by metal-organic vapor-phase epitaxy and reverse leakage current in vertical p–n diodes on a free-standing GaN substrates. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 58, SCCB24 (2019).

Wach, F. et al. Low field vertical charge transport in the channel and buffer layers of GaN-on-Si high electron mobility transistors. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 41, 1754–1757 (2020).

Yacoub, H. et al. Effect of carbon doping level on static and dynamic properties of AlGaN/GaN heterostructures grown on silicon. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 65, 3192–3198 (2018).

Besendörfer, S. et al. Methodology for the investigation of Threading dislocations as a source of vertical leakage in AlGaN/GaN-HEMT heterostructures for power devices. J. Appl. Phys. 125, 095704 (2019).

Besendörfer, S. et al. Interplay between C-doping, Threading dislocations, breakdown, and leakage in GaN on Si HEMT structures. AIP Adv. 10, 045028 (2020).

Brunner, F., Brusaterra, E., Bahat-Treidel, E., Hilt, O.& Weyers, M. GaN drift layers on Sapphire and GaN substrates for 1.2 kV class vertical power devices. Phys. Rapid Res. Ltrs. 18, 2400013 (2024).

Brusaterra, E. et al. Optimization of vertical GaN drift region layers for avalanche and Punch-Through Pn-Diodes. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 44, 388–391 (2023).

Besendörfer, S. et al. The impact of dislocations on AlGaN/GaN Schottky diodes and on gate failure of high electron mobility transistors. Sci. Rep. 10, 17252 (2020).

Ganichev, S. D. et al. Distinction between the Poole-Frenkel and tunneling models of electric-field-stimulated carrier emission from deep levels in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 61, 10361–10365 (2000).

Kuksenkov, D. V., Temkin, H., Osinsky, A., Gaska, R. & Khan, M. A. Origin of conductivity and low-frequency noise in reverse-biased GaN p-n junction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 72, 1365–1367 (1998).

Chien, N. D. et al. Theoretical evaluation of maximum electric field approximation of direct band-to-band tunneling Kane model for low bandgap semiconductors. J. Phys. : Conf. Ser. 726, 012002 (2016).

Zhang, H., Miller, E. J. & Yu, E. T. Analysis of leakage current mechanisms in Schottky contacts to GaN and Al0.25Ga0.75 N∕GaN grown by molecular-beam epitaxy. J. Appl. Phys. 99, 023703 (2006).

Yang, Q. K., Fuchs, F., Schmitz, J. & Pletschen, W. Investigation of trap-assisted tunneling current in InAs/(GaIn)Sb superlattice long-wavelength photodiodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 4757–4759 (2002).

Bisi, D. et al. Deep-Level characterization in GaN HEMTs-Part I: advantages and limitations of drain current transient measurements. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 60, 3166–3175 (2013).

Ganichev, S. D. et al. Carrier tunneling in High-Frequency electric fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 2409–2412 (1998).

Mukherjee, K. et al. Understanding the leakage mechanisms and breakdown limits of vertical GaN-on-Si p + n – n diodes: the road to reliable vertical mosfets. Micromachines 12, 445 (2021).

Qwah, K. S., Robertson, C. A., Wu, Y. R. & Speck, J. S. Modeling dislocation-related reverse bias leakage in GaN p–n diodes. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 36, 075001 (2021).

Robertson, C. A., Qwah, K. S., Wu, Y. R. & Speck, J. S. Modeling dislocation-related leakage currents in GaN p-n diodes. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 245705 (2019).

Koller, C., Pobegen, G., Ostermaier, C. & Pogany, D. Evidence of defect band in carbon-doped GaN controlling leakage current and trapping dynamics. in 2017 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 33.4.1–33.4.4IEEE, San Francisco, CA, USA, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2017.8268491

Scales, Z. F., Koller, C., Lymperakis, L., Nelhiebel, M. & Stoeger-Pollach, M. The role of carbon segregation in the electrical activity of dislocations in carbon doped GaN. J. Appl. Phys. 136, 045704 (2024).

Besendörfer, S., Meissner, E. & Friedrich, J. Statistical investigation of dislocation induced leakage current paths in AlGaN/GaN HEMT structures on Si and the impact of growth conditions. Appl. Phys. Express. 15, 095502 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action of Germany (03EN4033A, 03EN4033E, and 03EN4033F) - HoverGaN. This work was partly supported by ECSEL JU through the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program and Germany, France, Belgium, Austria, Sweden, Spain, and Italy, under Grant 101007229.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.D.K. planned the series of experiments, performed IV, EL, and ECCI analyses, modeled electrical data, and wrote the manuscript. R.N. aided in data collection and analysis. A.T. performed TEM analysis and wrote manuscript sections corresponding to TEM. S.B. designed pin-diode layout. E.M. and R.W. advised, reviewed, and corrected the writing of the manuscript. F.B. designed, developed, and performed MOVPE sample growth. E.T. designed layout and epitaxial layer stack of the pn-diodes and processed the heterostructures into functional pn-diodes together with E.B. J.S. coordinated and advised all research efforts. All authors discussed and reviewed the contents of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kinstler, A.D., Neumann, R., Taylor, A.A. et al. Direct investigation of localized leakage currents in GaN-on-sapphire pn-diodes. Sci Rep 15, 39578 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25338-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25338-0