Abstract

Recycling construction and demolition waste (C&DW) into recycled concrete aggregates (RCA) is a sustainable strategy to reduce resource consumption and emissions. Most life cycle assessments (LCAs) focus on a single country and region, limiting broader applicability. This study conducts a novel comparative LCA of C&DW recycling systems across six countries and regions. By evaluating energy consumption, global warming potential (GWP), and fossil CO2 emissions in recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) production, significant regional differences are revealed, largely influenced by infrastructure, processing efficiency, and transport. In countries with mature recycling systems, RCA production reduces GWP by up to 97% per ton compared to natural aggregates manufacturing. Conversely, longer transport distances or inefficient operations in less developed systems can offset these benefits. While RCA generally demonstrates lower environmental impacts, its advantage is highly context-dependent. However, standardized global guidelines remain challenging due to regional disparities in waste sources and processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The construction and demolition (C&D) sector accounts for considerable amounts of global solid waste1. By increasing rate of urbanization and infrastructure development, construction and demolition waste (C&DW) has become a serious problem in environmental and economic aspects. Traditional methods of waste management, like landfilling, aren’t more sustainable due to negative environmental impacts2. In response, recycling C&DW into reusable materials, such as recycled concrete aggregates (RCA), has gained notice as a viable strategy to mitigate these impacts. However, C&DW recycling faces systemic barriers across regions, including inconsistent regulatory frameworks, technological gaps, and economic viability challenges. For instance, developing economies often lack infrastructure for efficient sorting and processing, while developed regions struggle with market acceptance of recycled materials and high operational costs3,4.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as a critical tool for evaluating the environmental impacts of C&DW recycling processes. LCA provides a systematic framework to quantify the environmental burdens associated with the entire life cycle of a product or process, from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal5,6. By applying LCA, researchers and practitioners can identify key environmental footprints, compare alternative waste management strategies, and optimize processes to enhance sustainability. However, despite the growing body of literature on C&DW recycling, existing studies often lack a comprehensive, geographically diverse evaluation of environmental impacts, limiting the development of globally applicable sustainable practices. Most research focuses on single-country or regional analyses, neglecting critical variations in waste composition, energy grids, and recycling infrastructure across global contexts. This gap hinders the identification of transferable best practices and context-specific solutions.

Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of LCA to inform sustainable practices in the construction sector. Despite these advancements, comparative studies across diverse economic and regulatory contexts remain rare. Addressing this deficiency, the present study conducts a standardized multi-country LCA of construction and demolition waste (C&DW) recycling, with a focus on recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) production in Brazil, Colombia, Hong Kong, India, Mainland China, and Spain. These countries and regions were purposefully selected to represent a wide spectrum of recycling system maturity and to capture key contrasts in policy frameworks, technological adoption, and energy profiles, enabling a significant understanding of how regional factors influence sustainability outcomes. In this study, maturity is conceptualized as the degree of development of a C&DW recycling system, as indicated by regulatory stringency, technological advancement, market integration, and best practice adoption, enabling this study to reveal how local and systemic factors influence environmental sustainability across contexts.

This study uses LCA to evaluate the environmental impacts of C&DW recycling processes across multiple countries and regions, focusing on the production of RCA. The research adopts the ISO 14040 and 14044 standards to ensure methodological rigor and comparability of results. By providing in-depth, context-specific analysis of critical impact categories such as energy consumption, global warming potential (GWP), and fossil CO2 emissions, the study advances the field beyond generalized findings and offers actionable insights into how regional factors shape sustainability outcomes. The methodology is structured around key phases of LCA: goal and scope definition, life cycle inventory (LCI), life cycle impact assessment (LCIA), and interpretation of results. The cut-off system model is selected to streamline the analysis of multi-output processes, ensuring a clear separation of environmental burdens and benefits associated with waste treatment and resource recovery. Data for the LCI is sourced from a combination of academic literature, industry reports, and the Ecoinvent database, providing a robust foundation for the analysis. The functional unit of 1 kg of recycled concrete aggregate is used to standardize comparisons across different locations and processes.

Moreover, this study provides critical insights into how C&DW recycling practices vary across different regions, offering a foundation for more targeted and effective waste management strategies. By comparing energy consumption, emissions, and processing methods, the analysis reveals that environmental performance depends not only on technology but also on regional infrastructure, policy frameworks, and material flows. These findings move beyond broad generalizations, enabling stakeholders to identify specific areas for improvement based on their local context. The practical implications of this work extend across multiple levels of decision-making. For policymakers, the results highlight where regulatory interventions, such as incentives for electrification or requirements for recycled content, could have the greatest impact. Industry operators can use comparative data to benchmark their performance and prioritize investments in cleaner technologies or logistics optimization. Meanwhile, the standardized LCA approach developed here offers researchers a replicable methodology for future cross-regional studies.

While this study focuses on environmental metrics, achieving full comparability requires decomposition analysis from the source. This framework paves the way for more comprehensive assessments. Future work could integrate economic viability studies to identify cost-effective recycling models or explore social factors, such as the employment impacts of transitioning from informal to formal recycling sectors. Such multidimensional analyses would provide a broader understanding of how C&DW management contributes to sustainable development goals. Ultimately, this research underscores that achieving meaningful progress in C&DW recycling requires both global perspectives and localized solutions. The variations uncovered across regions suggest that prescriptive, one-size-fits-all approaches may be less effective than adaptable strategies that account for regional capacities and constraints. By building on these findings, the construction sector can develop more novel roadmaps toward circularity, ones that balance environmental imperatives with practical implementation realities across diverse economic and operational contexts.

Literature review

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as a pivotal tool in evaluating the environmental impacts of C&DW recycling, offering insights into the sustainability of different waste management strategies. While existing studies have applied LCA to C&DW recycling, this study addresses three critical gaps in limited cross-country comparisons of operational practices, inconsistent methodological approaches, and insufficient specificity in life cycle inventory (LCI) data for key processes like on-site equipment usage.

Recent studies have increasingly leveraged LCA to evaluate the environmental performance of diverse C&DW recycling strategies. A comparative analysis of end-of-life scenarios for carbon-reinforced concrete has highlighted the environmental advantages of recycling over landfilling7. The environmental impacts of various waste concrete recycling approaches for prefabricated components have been shown to be minimized by incorporating recycled aggregates and supplementary cementitious materials8. Optimization of recycling processes has been emphasized as critical for reducing environmental impacts and carbon emissions9, and the implementation of advanced sorting technologies has been demonstrated to significantly lower the environmental footprint in C&DW management, as evidenced in Hong Kong10. In Italy, the environmental evaluation of recycled aggregates underscores the role of recycling in mitigating resource depletion and landfilling11. The analysis of alternative recycling streams has been broadened by studies examining all-solid-waste high-strength concrete produced from waste rock aggregates, thereby enhancing the generalizability of comparative assessments beyond traditional concrete recycling12. Broader studies further reveal that integrating industrial by-products into concrete can substantially lower greenhouse gas emissions and energy use, with alternative binders like LC3 and geopolymer providing additional sustainability benefits compared to conventional options13,14.

Technological and contextual considerations are also pivotal. Evidence from Malaysia suggests that prefabricated steel PPVC structures can provide long-term environmental and economic gains despite higher initial energy inputs15. (Kim, 2011) found transparent composite facades (TCFS) outperform glass curtain walls (GCWS) in energy efficiency and CO2 emissions over 40 years, underscoring the critical role of material selection in sustainable construction16. Transportation logistics have been identified as a significant factor influencing the life cycle impacts of natural and recycled aggregate concrete17. Additionally, innovative processes such as optimized carbonation of waste concrete powder and accelerated carbonation treatment have demonstrated potential for substantial energy reductions and, in some cases, achieving carbon-negative outcomes18,19. Nevertheless, these studies generally remain limited by their geographic scope, thus constraining their generalizability to other regions with distinct waste streams, infrastructure, and policy environments.

For benchmarking and cross-country analysis, comprehensive reviews of environmental pressures in resource extraction, such as those quantifying CO2 emissions, water use, and land requirements, provide essential datasets for regional impact comparisons and help address gaps in emissions modeling20. Methodological advancements, including the application of multi-criteria decision analysis and dynamic system boundaries, have been proposed to expand LCA beyond static ISO frameworks and better account for transitional scenarios21. Stakeholder analysis on the practical implementation of advanced recycling techniques, such as carbonation curing approach, has further highlighted the relevance of policy engagement and market mechanisms in promoting urban sustainable governance22.

While regional studies (e.g., Italy and the UK) confirm recycling’s benefits over landfilling11,23, their localized focus limits applicability to diverse global contexts. This study bridges that gap by analyzing C&DW recycling across developed and developing economies using standardized functional units and system boundaries. Methodological inconsistencies in LCA studies further complicate the assessment of C&DW recycling’s environmental performance. Many studies have employed varying functional units, system boundaries, and impact categories, leading to challenges in comparing results across studies. For example24, one study identified significant inconsistencies in the definition and application of functional units in LCA studies on C&DW recycling, which can deviate interpretation of environmental impacts. Similarly, the lack of standardized environmental indicators has been a repetitive issue, with studies often employing different metrics to assess impacts, such as energy consumption and global warming potential24,25. These methodological discrepancies highlight the need for standardized LCA methodologies that ensure comparability and reliability of results across different studies.

Data gaps, particularly concerning energy and diesel consumption, have also been a critical limitation in existing LCA studies on C&DW recycling. Many studies have relied on secondary data or averaged values, which may not accurately reflect the real-world energy demands and emissions associated with recycling processes26,27. This lack of detailed LCI data can lead to underestimations of the environmental impacts of C&DW recycling, particularly in terms of direct emissions of CO2, CH4, and N2O from diesel usage. Addressing these data gaps is essential for enhancing the accuracy and relevance of LCA findings and for informing sustainable waste management practices.

This study addresses three research gaps in C&DW recycling through a multinational comparison across different technological and regulatory contexts. Using a cut-off system model with 1 kg RCA as the functional unit, we analyze transportation, sorting, and processing stages through three key indicators: energy consumption, GWP, and fossil CO2 emissions. These metrics were selected for their relevance to recycling operations and policy applications28, providing comparable environmental impact assessment across countries.

The resulting framework offers policymakers benchmarks for comparing recycling performance across regions, while giving operators specific targets for reducing energy use and emissions, particularly valuable for developing economies where C&DW recycling infrastructure is rapidly expanding. By resolving previous methodological inconsistencies and data limitations, this work enables more accurate lifecycle comparisons and better-informed decisions about sustainable construction waste management globally.

Methodology

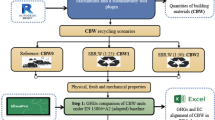

This study applies LCA by ISO standards to evaluate the environmental impacts of recycling construction and demolition waste. The process begins by defining the goal, scope, and system boundaries, utilizing a cut-off system model to simplify multi-output processes. Life cycle inventory data is sourced from a range of reginal-specific cases, focusing on energy consumption and emissions. Environmental impacts are then quantified, offering a systematic framework for analyzing and enhancing sustainable waste management practices, as the general framework for LCA demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Life cycle assessment

LCA is a method used to comprehensively evaluate and quantify the environmental impacts of products or processes. When it comes to managing C&DW, LCA can complement the traditional waste management hierarchy of reducing, reusing, recycling, and disposing29. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has set out the 14040 and 14044 standards, which offer a standardized framework for conducting and reporting LCA studies5,6. These standards outline an LCA study in four stages, including goal and scope definition, life cycle inventory, life cycle impact assessment, and interpretation.

The LCI comprises various independent unit processes forming the system collectively. Some of these processes generate multiple outputs. Each unit process must be simplified to produce a single output to ensure effective LCA calculations. Consequently, a system model separates multi-output unit processes into several single-output processes and interconnects them, consolidating the inputs and outputs into a cohesive product system30,31. The Ecoinvent database31 offers three system models for calculating impacts from the same raw data, each using different assumptions to assess environmental impacts:

-

1.

Cut-off System Model: Separates waste production impacts from treatment benefits, assigning all burdens to production without crediting recovered resources.

-

2.

APOS System Model: Combines production and treatment impacts, allocating them between the reference and recycled products. Both cut-off and APOS are attributional but differ in waste treatment handling.

-

3.

Consequential System Model: Incorporates market dynamics and indirect policy effects, distributing impacts across byproducts while considering broader economic consequences.

Both attributional and consequential modeling approaches have their own advantages and limitations. Attributional approaches focus on quantifying the current environmental impacts of a product, while consequential models aim to capture the potential future impacts or consequences of marginal changes in product demand32. Some argue that the results of consequential models are highly sensitive to geography and local economic factors, making their findings challenging to communicate33. In contrast, attributional approaches provide more interpretable results due to their simplicity34,35.

This study employs the cut-off model to enable consistent comparison of environmental impacts across sites and countries, avoiding speculative projections about future production or technology shifts. The consequential model was not feasible due to limited access to site-specific market data and marginal supply information. However, the cut-off approach has limitations: it assigns all waste treatment burdens to production without crediting material recovery, potentially overestimating impacts for high-recycling systems and neglecting downstream market effects. These constraints should be acknowledged, especially when assessing circular economy systems where recycling and secondary markets are significant36.

Goal and scope

In this analysis, the system boundaries include the transportation of waste to the recycling plant as well as the recycling operations themselves. The recycling process involves several key stages, facilitated by specialized equipment such as loaders, excavators, feeders, crushers, sieves, electromagnets for metal separation, and belt conveyors37. Inventory data for each country and site were sourced from plant surveying, supplemented by complementary data obtained from equipment manufacturers. Additional background data, where necessary, were derived from established databases such as Ecoinvent, and peer-reviewed literature, ensuring comprehensive and reliable life LCI inputs. The data inputs are electricity and diesel, the outputs are CO2, N2O, and CH4 emissions from diesel consumption for the recycling process. Additionally, environmental impacts, including indicators such as energy consumption, global warming potential (CO2, e), and fossil CO2 emissions for producing 1 kg of recycled aggregate from C&DW.

The functional unit is determined as 1 kg of concrete, which is the basis for comparison. Selecting an appropriate functional unit is essential for comparing and evaluating the LCA of alternative products and services. Different functional units can yield varying results for the same product or system38,39. The selection of 1 kg of concrete as the functional unit was based on its suitability for material-level environmental impact assessment, ensuring direct comparability with existing LCA databases and studies while maintaining methodological consistency. This mass-based approach provides unambiguous impact allocation that remains unaffected by variables like density variations in recycled aggregates or strength differences in mix designs, which would complicate volume- or performance-based functional units. While alternative functional units (e.g., 1 m3 for volume or strength-based metrics) may better reflect specific construction applications, they introduce additional assumptions and system boundary complexities that fall outside this study’s focus on fundamental production and recycling impacts5,6.

Life cycle inventory (LCI)

Life cycle inventory (LCI), as outlined by ISO 14040, is an analytical process that entails gathering and finalizing data on the inputs and outputs, or the flow of life cycle stages, for a product throughout its development40. The LCI compiles data for each unit process within the defined system boundary. This data includes the inputs and outputs of resource flows, as well as emissions to air. A unit process is the smallest component of the system for which data is collected, performing a specific sub-function that contributes to the system’s overall function. For processes such as electricity production and transmission, diesel production, and road transport, data were sourced from various references, including government reports, research articles, and the Ecoinvent database.

This study leverages first-hand operational data from recycling plants across countries to conduct a rigorous comparative life cycle assessment of recycled concrete aggregate production. The analysis draws on verified plant-level measurements of electricity and diesel consumption from sources including equipment monitoring systems, government energy audits, and peer-reviewed industrial case studies, ensuring data reliability while acknowledging regional variations in measurement protocols.

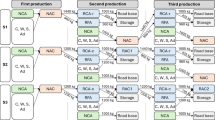

The RCA production processes vary significantly across plants, as evidenced by flowcharts and equipment analyses. While some facilities employ sophisticated, automated systems with high energy efficiency, others rely on traditional, labor-intensive methods. The flow diagram of RCA production among various plants has been shown in Fig. 2. These technological differences directly impact production quality, operational efficiency, and environmental performance. Notably, plants demonstrate varying degrees of dependence on diesel-powered versus electric equipment, creating distinct energy consumption profiles. Through systematic analysis of these process flows and their associated data, environmental impacts and opportunities for optimization could be quantified accurately, particularly in transitioning from diesel-dependent operations to cleaner, more efficient technologies. The raw inventory data for each site and production processes have been extracted and processed from local manufacturers and peer-reviewed literature41,42,43.

This research initially calculates the diesel consumption for C&DW transportation to the recycling plant and machinery such as loaders and excavators operating within the recycling site. In this part, diesel consumption for the transportation of C&DW to recycling units is added to the diesel consumption of handling equipment in the recycling site. For instance, in Brazil, the average transport distance from the construction and demolition waste (C&DW) site to the six nearest recycling plants in São Paulo has been calculated as 20 km, measured from the city’s central point. As the demolished concrete arrives at the site, waste processing begins. During these processes, electrical energy consumption is estimated based on the usage of each piece of equipment, as detailed in the equipment catalog or the electricity bills provided by the manufacturer. The total electrical energy consumption is then calculated in kilowatt-hours (kWh).

Moreover, Table 1 provides a comprehensive inventory of various processes extracted from the Ecoinvent and local databases, detailing their cumulative energy demand (CED) and associated CO2 emissions. This table includes data on electricity production and transmission, diesel production, road transport, wood pellet production, and waste disposal. Each process is quantified in terms of its functional unit (FU), with corresponding values for energy consumption (MJ/FU) and CO2 emissions (kg/FU).

Life cycle impact assessment (LCIA)

In life cycle impact assessment, relevant environmental impact categories like Global Warming Potential (GWP), Energy Consumption, and Fossil CO2 Emissions are selected. The inventory data is converted to potential environmental impacts for each category. Then, the quantities of demolished concrete waste, electricity, and diesel are considered as inputs to the model. The outputs of the process within the model’s scope include the production of 1 kg of RCA. Other outputs are CO2, CH4, and N2O emissions. Afterward, the environmental indicators such as energy consumption, global warming potential, and fossil CO2 emissions are calculated. Finally, energy consumption is assessed using the Cumulative Energy Demand method (version 1.11). The Global Warming Potential (GWP) is evaluated with the IPCC method, applying a 100-year time horizon (2021 version 1.01). Fossil CO2 emissions are quantified using the fossil CO2 into the atmosphere method, facilitated by Simapro software version 9.4.

Results and discussion

Comparative environmental impact analysis

The environmental performance of recycling is influenced by various factors, including transportation distance, energy consumption during plant operations, and the electricity mix used. Using comparative tables and graphs, differences between processes and impacts are investigated. The unit processes and environmental indicators are calculated based on the inventory data in Table 2.

The analysis reveals three distinct energy consumption models in global C&DW recycling plants:

-

1.

Electrically dominant systems like Shanghai’s plant, which achieves near-zero diesel use but remains highly energy-intensive.

-

2.

Balanced hybrid approaches exemplified by Brazil’s Odebrecht plant, combining moderate diesel use with high electrification supported by renewable energy.

-

3.

Diesel-dependent operations seen in Mumbai and Hong Kong.

An inverse relationship exists between electricity and diesel use, suggesting substitution opportunities. While complete electrification remains ideal, strategic electrification of high-load processes can yield significant benefits. Spain’s La Blonga plant emerges as an outlier with dual energy intensity, potentially indicating unique processing requirements or inefficiencies requiring further investigation.

The analysis of CO2, CH4, and N2O direct emissions from diesel across various locations in Fig. 3a, b,c reveals significant differences in environmental impact. Shanghai Plant maintains its position as a low emission benchmark, with minimal diesel related CO2 emissions directly reflecting its near zero diesel dependence. At the other extreme, Mumbai Maharashtra Plant and Spain La Blonga Plant show the highest emission levels, corresponding to their heavy reliance on diesel-powered equipment. Brazil’s facilities illustrate contrasting profiles: the Odebrecht Plant shows intermediate emissions consistent with a partially electrified, hybrid energy model, while the São Bernardo do Campo Plant exhibits higher diesel-related emissions, indicative of more conventional, fuel-dependent operations. Similarly, Colombia’s Greco Plant and India’s IL&FS Plant present balanced hybrid profiles, combining moderate diesel use with some degree of electrification. These regional differences underscore how operational decisions regarding equipment power sources directly shape environmental outcomes.

The climate implications of these emissions necessitate particular attention. While CO2 dominates in terms of total quantity, the presence of N2O (with a global warming potential 298 times that of CO2) means even trace emissions can significantly influence a facility’s overall climate impact44. Plants like India Mumbai and Spain La Blonga, which show the highest N2O emissions, may have disproportionate climate impacts despite what appear to be modest absolute emission values. This finding suggests that emission reduction strategies should prioritize not just total diesel consumption but also technologies that specifically target nitrogen oxide formation during combustion.

Direct emissions from diesel consumption (a) CO₂ (b) N₂O (c) CH₄, generated using Python 3.13 (https://www.python.org/).

Figure 4a, b shows the trade-offs between energy consumption and environmental impacts across C&DW recycling facilities. When examining energy consumption patterns, we observe significant variation between facilities. These differences highlight how operational choices, regional energy sources, and output material quality standards shape climate performance. The Shanghai Plant records the highest electricity and total energy use among all sites. Despite low diesel consumption, it exhibits relatively high fossil CO2 emissions, suggesting that while electrification reduces direct emissions, its environmental benefits are limited by the fossil intensity of China’s electricity grid. Brazil’s Odebrecht and São Bernardo do Campo Plants highlight intra-country contrasts. The Odebrecht Plant relies more on electricity and benefits from Brazil’s cleaner, hydropower-based grid, leading to lower fossil CO2 emissions. In contrast, the São Bernardo do Campo Plant has greater diesel dependence but still shows slightly lower fossil CO2 emissions and comparable GWP. This reflects lower total energy consumption, highlighting that both fuel type and process intensity influence emissions. This underscores the importance of grid decarbonization alongside electrification to fully realize climate benefits.

Plants like India Maharashtra and Hong Kong Tuen Mun demonstrate that relatively moderate energy use can still result in disproportionately high emissions due to diesel reliance. Their fossil CO2 and GWP values exceed those of more electrified sites, confirming the need for fuel-specific environmental standards in addition to general energy efficiency metrics. Conversely, Colombia’s Greco Plant and India’s IL&FS Plant exemplify successful hybrid models. With limited diesel and moderate electricity use, both achieve low fossil CO2 emissions and GWP, indicating that balanced operational strategies can deliver strong environmental outcomes even without full electrification. These cases highlight the potential for efficiency gains through operational optimization. The comparison between Spain’s La Blonga and Córdoba Plants further illustrates the role of modernization, output specifications, and process choices. La Blonga plant shows high GWP and fossil CO2 values due to substantial diesel and electricity use, reflecting a transitional hybrid system. This may also stem from the production of higher-quality recycled materials, which often require more energy-intensive processing to meet market standards. Meanwhile, Córdoba plant demonstrates that mature markets can operate efficiently with less emissions by using lower energy input per output. These findings suggest that while full electrification remains a long-term ideal, phased improvements can yield meaningful climate benefits, especially when aligned with cleaner electricity sources. Tiered policy frameworks should reflect local readiness, output quality expectations, and grid contexts to support this transition.

Global warming potential (a) (circle size) and Fossil CO2 emission (b) (circle size) vs. energy consumption across global plants, generated using Python 3.13 (https://www.python.org/).

These findings serve to redefine priorities for sustainable C&DW management by indicating the ways in which regional variations in environmental performance are shaped by underlying systemic barriers. First, the results underscore that the primary challenge is not simply energy reduction, but the procurement of clean energy, a shift that is often impeded by region-specific regulatory frameworks and the availability of renewable energy infrastructure. This finding aligns with several previous LCA studies10,11, which similarly emphasize the decisive impact of regulatory and infrastructural factors on decarbonization potential in recycling systems. Second, the validation of hybrid systems as transitional solutions highlights the importance of regulatory and market incentives in facilitating the phased adoption of electrification, while the absence of clear policy-driven phase-out mechanisms can impede long-term sustainability objectives. Third, the analysis demonstrates that output material quality, which can substantially influence energy and fuel demands, is contingent upon both technological capacity and local market requirements, the patterns corroborated by previous studies highlighting that regions with stricter regulatory standards or higher demand for specialized recycled materials often face increased processing burdens and emissions14.

Importantly, the results highlight the critical role of context-specific innovation, defined as technological, operational, or organizational strategies, that are particularly effective within the unique regulatory, socioeconomic, and infrastructural conditions of a given region. For instance, Shanghai’s advanced automation exemplifies an innovation optimized for its dense urban setting, high energy demand, and particular labor market dynamics. While automation has delivered substantial environmental benefits in Shanghai, its direct transferability to regions with different economic structures or infrastructural constraints may be limited. Conversely, Córdoba’s efficient conventional processes represent a distinct form of innovation, achieving notable performance improvements within the context of its available resources and regulatory environment. Comparative analysis with other plants in the study reveals that Córdoba’s operational model, while highly effective locally, may require significant adaptation to yield similar benefits in other settings. Practical implementation requires regional innovation hubs to adapt to the best global practices, supported by transparent benchmarking of energy sources, emissions, and output quality standards.

Comparative analysis of natural aggregate and recycled concrete aggregate

The comparison of natural aggregates (NA) and recycled aggregates (RCA), considering the data from Tables 2 and 3, highlights significant differences in their environmental impacts. Natural aggregates demonstrate considerable variability in their environmental impacts, with global warming potential (GWP and energy consumption. This wide range reflects differences in extraction methods (crushed vs. rolled) and aggregate types (coarse vs. fine), with crushed materials generally showing higher impacts due to more energy-intensive processing requirements. In contrast, recycled aggregates’ environmental impacts are consistently at or below the lower end of the natural aggregate spectrum, demonstrating RCA’s superior environmental performance.

The data reveals several important patterns. First, the processing method significantly influences environmental impacts for both material types, with crushing operations consistently showing higher energy demands and emissions than rolling. Second, while some natural aggregate scenarios (particularly rolled coarse aggregates) can approach RCA performance levels, recycled materials offer more consistent and reliably lower impacts.

These findings strongly support the use of recycled aggregates as a more sustainable alternative to natural materials in construction applications. The environmental benefits of RCA are particularly pronounced in regions with well-developed recycling infrastructure, where optimized processing can minimize energy use and emissions. However, the analysis also suggests opportunities for improving natural aggregate production through the adoption of less energy-intensive processing methods and cleaner energy sources. For maximum environmental benefit, project specifications should prioritize RCA where technically feasible while continuing to optimize natural aggregate production for applications where raw materials remain necessary.

Limitations

It is important to recognize several methodological and data-related limitations inherent in this study. The adoption of the cut-off model, which attributes all environmental burdens associated with waste treatment to the production phase without assigning credits for recovered resources, constitutes a primary constraint. While this approach facilitates methodological consistency and comparability across diverse regional contexts, it may inadvertently lead to an overestimation of environmental impacts, particularly in regions characterized by advanced, high-recycling systems where material recovery and secondary market integration are substantial. The decision to adopt the cut-off approach, rather than a consequential modeling framework, was informed by a constellation of factors extending beyond the frequently cited limitation of access to site-specific market data. Notably, the significant heterogeneity in data availability and quality, the diverse landscape of end-use markets for recovered materials, and the absence of harmonized reporting standards for downstream product flows across countries collectively precluded the reliable allocation of credits for recovered resources or the modeling of downstream market effects. Notable disparities in both the quality and availability of data arose from differences in regional data collection methodologies, reporting standards, and the degree of transparency among governmental and industry sources. These inconsistencies occasionally required the use of estimations and directly influenced the selection of countries and processes, as the study prioritized jurisdictions with sufficiently robust and harmonized data to preserve the validity and comparability of the analysis. The reported impact indicators should be regarded as conservative estimates, particularly for contexts with mature circular economy practices, where the omission of credits for material recovery and market effects may obscure the true extent of environmental benefits. Consequently, caution is warranted when implementing these findings to policy and industry applications, especially in settings with high levels of market integration.

Additionally, the methodological framework employed in this study exhibits inherent limitations with respect to capturing the dynamic trajectory of technological innovation, as it does not incorporate prospective LCA or systematic technological forecasting. Systematic analysis of emerging innovations, such as through patent data, enables designers to anticipate and incorporate new materials and manufacturing methods while prospectively assessing their environmental impacts using LCA methodologies52, thus providing a more dynamic and forward-looking sustainability evaluation. Such an approach would not only facilitate evaluation of sectoral and cross-domain shifts precipitated by technological advancement, but also support iterative improvement through interdisciplinary stakeholder engagement and the establishment of robust feedback mechanisms. While narrowing the scope of data sources may partially address challenges of information overload, it cannot fully resolve the complexities in assessing the sustainability implications of rapidly evolving technological landscapes. Future research should prioritize the development of harmonized data standards, enhanced transparency in reporting, as well as the integration of prospective LCA approaches to more holistically capture the complex, dynamic, and circular nature of contemporary construction and demolition waste management systems.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive comparison of the environmental performance of construction and demolition waste recycling facilities across different regions. The findings demonstrate clear environmental advantages of recycled aggregates over natural alternatives. Recycled materials consistently show lower carbon footprints and energy demands compared to conventional natural aggregates, particularly when contrasted with energy-intensive crushed stone production. However, certain processing methods for natural materials, especially rolled aggregates, can approach the efficiency levels of recycling in optimal conditions.

This study also underscores the complexity of setting a complete standard guideline for comparison across regions. It highlights the importance of considering regional contexts, often requiring a case-by-case or country-by-country approach, with decomposition analysis needed for full comparability. Regional analysis highlights distinct operational models. European facilities showcase advanced approaches, from Spain’s highly efficient Córdoba plant to its La Blonga facility which prioritizes premium quality outputs through more energy-intensive processes. Asian operations present striking contrasts, with China’s electrified plants outperforming diesel-dependent systems in space-constrained urban centers. Developing economies face particular challenges in balancing energy use with emissions, often relying on transitional hybrid systems. The study identifies several actionable pathways for advancing sustainability in C&DW recycling. Process electrification, optimization of material flows, and the integration of renewable energy sources are highlighted as key strategies. For regions with less mature recycling infrastructure, a phased transition from diesel-powered to hybrid and eventually fully electrified systems is recommended.

These findings hold significant implications for both policymakers and industry leaders. Policymakers can leverage regional differences in energy consumption and emissions profiles to develop targeted regulatory frameworks, incentives, and investment priorities that address local systemic barriers while capitalizing on context-specific strengths. Comparative benchmarking, as presented in this analysis, can inform the setting of realistic targets and support the dissemination of best practices tailored to the maturity and needs of each region. For industry practitioners, this study recommends adopting advanced automation where appropriate, optimizing operational processes by drawing on effective models from comparable regions, and investing in technologies and practices with demonstrated efficacy in reducing energy consumption and emissions. Aligning these operational decisions with data-driven insights from this study enables the sector to enhance sustainability performance and proactively respond to evolving regulatory and market dynamics. Looking forward, this research establishes a foundation for ongoing improvements in construction waste management. Future efforts should focus on integrating emerging technologies, enhancing material quality standards, and developing circular business models. Such advancements will be crucial for realizing the full environmental potential of construction material recycling across global markets. The study underscores that while technical solutions exist, their successful implementation requires tailored approaches that consider regional economic and operational realities. By combining global best practices with local adaptations, the construction sector can significantly reduce its environmental footprint while meeting growing infrastructure demands.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

References

Akhtar, A. & Sarmah, A. K. Construction and demolition waste generation and properties of recycled aggregate concrete: A global perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 186, 262–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.085 (2018).

Blengini, G. .A. Resources and waste management in Turin (Italy): the role of recycled aggregates in the sustainable supply mix. J. Clean. Prod. 18(10–11), 1021–1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.01.027 (2010).

Charef, R., Morel, J. C. & Rakhshan, K. Barriers to implementing the circular economy in the construction industry: A critical review. Sustainability 13 (23), 12989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132312989 (2021).

Tamirat, Y., Hassan, A., Tseng, M. L., Wu, K. J. & Ali, M. H. Sustainable construction and demolition waste management in somaliland: regulatory barriers lead to technical and environmental barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 297, 126717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126717 (2021).

Standardization, I. O. Environmental management: life cycle assessment; Principles and Framework. (ISO, 2006).

Standard, I. Environmental management-Life Cycle assessment-Requirements and Guidelines (ISO, 2006).

Backes, J. G., Del Rosario, P., Luthin, A. & Traverso, M. Comparative life cycle assessment of end-of-life scenarios of carbon-reinforced concrete: a case study. Appl. Sci. 12 (18), 9255. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12189255 (2022).

Jian, S. M., Wu, B. & Hu, N. Environmental impacts of three waste concrete recycling strategies for prefabricated components through comparative life cycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 328, 129463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129463 (2021).

Qiao, L. et al. Life cycle assessment of three typical recycled products from construction and demolition waste. J. Clean. Prod. 376, 134139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134139 (2022).

Hossain, M. U., Wu, Z. & Poon, C. S. Comparative environmental evaluation of construction waste management through different waste sorting systems in Hong Kong. Waste Manage. 69, 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2017.07.043 (2017).

Colangelo, F., Petrillo, A. & Farina, I. Comparative environmental evaluation of recycled aggregates from construction and demolition wastes in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 798, 149250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149250 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Performance assessment of all-solid-waste high-strength concrete prepared from waste rock aggregates. Materials 18 (3), 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18030624 (2025).

Kanagaraj, B., Anand, N., Raj, R. S. & Lubloy, E. Techno-socio-economic aspects of Portland cement, geopolymer, and limestone calcined clay cement (LC3) composite systems: a-state-of-art-review. Constr. Build. Mater. 398, 132484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132484 (2023).

Kanagaraj, B., Anand, N., Alengaram, U. J., Raj, R. S. & Lubloy, E. A Comprehensive Review on Life-cycle assessment of concrete using industrial by-products. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscee.2025.101260 (2025).

Balasbaneh, A. T. & Ramli, M. Z. A comparative life cycle assessment (LCA) of concrete and steel-prefabricated prefinished volumetric construction structures in Malaysia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27 (34), 43186–43201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10141-3 (2020).

Kim, K. H. A comparative life cycle assessment of a transparent composite façade system and a glass curtain wall system. Energy Build. 43 (12), 3436–3445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2011.09.006 (2011).

Hasheminezhad, A., King, D., Ceylan, H. & Kim, S. Comparative life cycle assessment of natural and recycled aggregate concrete: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 950, 175310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175310 (2024).

Kravchenko, E., Sauerwein, M., Besklubova, S. & Ng, C. W. W. A comparative life cycle assessment of recycling waste concrete powder into CO2-Capture products. J. Environ. Manage. 352, 119947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119947 (2024).

Yunhui, P., Li, L., Shi, X., Wang, Q. & Abomohra, A. A comparative life cycle assessment on recycled concrete aggregates modified by accelerated carbonation treatment and traditional methods. Waste Manage. (New York N Y). 172, 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2023.10.040 (2023).

Tost, M. et al. Metal mining’s environmental pressures: A review and updated estimates on CO2 Emissions, water Use, and land requirements. Sustainability 10 (8), 2881. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082881 (2018).

Amaro, S. L. et al. Multi-criteria decision analysis for evaluating transitional and post-mining options—an innovative perspective from the EIT reviris project. Sustainability 14 (4), 2292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042292 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Market stakeholder analysis of the practical implementation of carbonation curing on steel slag for urban sustainable governance. Energies 15 (7), 2399. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15072399 (2022).

Blay-Armah, A., Bahadori-Jahromi, A., Mylona, A. & Barthorpe, M. An LCA of Building demolition waste: a comparison of end-of-life carbon emission. Pro Inst. Civ. Engin -Was Rer Manag (2023).

Bayram, B. & Greiff, K. Life cycle assessment on construction and demolition waste recycling: a systematic review analyzing three important quality aspects. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 28 (8), 967–989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-023-02145-1 (2023).

Banias, G. F. et al. Environmental assessment of alternative strategies for the management of construction and demolition waste: A life cycle approach. Sustainability 14 (15), 9674. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159674 (2022).

Borghi, G., Pantini, S. & Rigamonti, L. Life cycle assessment of non-hazardous construction and demolition waste (CDW) management in Lombardy region (Italy). J. Clean. Prod. 184, 815–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.287 (2018).

Jain, S., Singhal, S. & Pandey, S. Environmental life cycle assessment of construction and demolition waste recycling: A case of urban India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 155, 104642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104642 (2020).

Munir, Q., Lahtela, V., Kärki, T. & Koivula, A. Assessing life cycle sustainability: A comprehensive review of concrete produced from construction waste fine fractions. J. Environ. Manage. 366, 121734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121734 (2024).

Manfredi, S. & Pant, R. Supporting Environmentally Sound Decisions for Construction and Demolition (C & D) Waste Management: A Practical Guide to Life Cycle Thinking (LCT) and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). (Publications Office, 2011).

Frischknecht, R. et al. The ecoinvent database: overview and methodological framework. pp) Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 10 (1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1065/lca2004.10.181.1 (2005). (7.

Wernet, G. et al. The ecoinvent database version 3 (part I): overview and methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 21 (9), 1218–1230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1087-8 (2016).

Ekvall, T. et al. Attributional and consequential LCA in the ILCD handbook. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 21 (3), 293–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-015-1026-0 (2016).

Searchinger, T. et al. Use of U.S. Croplands for Biofuels Increases Greenhouse Gases Through Emissions from Land-Use Change. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1151861 (2008).

Brander, M., Tipper, R., Hutchison, C. & Davis, G. Technical Paper: Consequential and attributional approaches to LCA: a Guide to policy makers with specific reference to greenhouse gas LCA of biofuels. (Econometrica press, 2008).

Ekvall, T. Attributional and consequential life cycle assessment. Sustainability Assessment at the 21st century. 13 (2019).

Allacker, K. et al. Allocation solutions for secondary material production and end of life recovery: proposals for product policy initiatives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 88, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2014.03.016 (2014).

Liu, X. et al. Discrepancies in life cycle assessment applied to concrete waste recycling: A structured review. J. Clean. Prod. 434, 140155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.140155 (2024).

Silva, R. V., de Brito, J. & Dhir, R. K. The influence of the use of recycled aggregates on the compressive strength of concrete: a review. Eur. J. Environ. Civil Eng. 19 (7), 825–849. https://doi.org/10.1080/19648189.2014.974831 (2015).

Visintin, P., Xie, T. & Bennett, B. A large-scale life-cycle assessment of recycled aggregate concrete: The influence of functional unit, emissions allocation and carbon dioxide uptake. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119243 (2019).

Ekvall, T. & Weidema, B. P. System boundaries and input data in consequential life cycle inventory analysis. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 9 (3), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02994190 (2004).

Agrela, F. et al. Environmental assessment, mechanical behavior and new leaching impact proposal of mixed recycled aggregates to be used in road construction. J. Clean. Prod. 280, 124362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124362 (2021).

Gayarre, F. L., Pérez, J. G., Pérez, C. L. C., López, M. S. & Martínez, A. L. Life cycle assessment for concrete kerbs manufactured with recycled aggregates. J. Clean. Prod. 113, 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.11.093 (2016).

Pradhan, S., Tiwari, B., Kumar, S. & Barai, S. Comparative LCA of recycled and natural aggregate concrete using particle packing method and conventional method of design mix. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.328 (2019).

Rizwan, M., Tanveer, H., Ali, M., Sanaullah, M. & Wakeel, A. Role of reactive nitrogen species in changing climate and future concerns of environmental sustainability. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-34647-2 (2024).

Dias, A. et al. Environmental and economic comparison of natural and recycled aggregates using LCA. Recycling 7 (4), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling7040043 (2022).

Braga, A. M., Silvestre, J. D. & de Brito, J. Compared environmental and economic impact from cradle to gate of concrete with natural and recycled coarse aggregates. J. Clean. Prod. 162, 529–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.057 (2017).

Estanqueiro, B., Dinis Silvestre, J., de Brito, J., Duarte, M. & Pinheiro Environmental life cycle assessment of coarse natural and recycled aggregates for concrete. Eur. J. Environ. Civil Eng. 22 (4), 429–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/19648189.2016.1197161 (2018).

Fraj, A. B. & Idir, R. Concrete based on recycled aggregates–Recycling and environmental analysis: A case study of paris’ region. Constr. Build. Mater. 157, 952–964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.09.059 (2017).

Tosic, N., Marinkovic, S., Dasic, T. & Stanić, M. Multicriteria optimization of natural and recycled aggregate concrete for structural use. J. Clean. Prod. 87, 766–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.10.070 (2015).

Hossain, M. U., Poon, C. S., Lo, I. M. & Cheng, J. C. Comparative environmental evaluation of aggregate production from recycled waste materials and Virgin sources by LCA. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 109, 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2016.02.009 (2016).

Marinković, S., Radonjanin, V., Malešev, M. & Ignjatović, I. Comparative environmental assessment of natural and recycled aggregate concrete. Waste Manage. 30 (11), 2255–2264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2010.04.012 (2010).

Spreafico, C. et al. Using patents to support prospective life cycle assessment: opportunities and limitations. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 30 (2), 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-024-02404-9 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the financial supports from the Innovandi Global Cement and Concrete Research Network, as part of its Core Project 11: LCCA/LCA study/framework for the comparison of different methods of recycling concrete.

Funding

This study is funded by the Core Project 11 of the Innovandi Global Cement and Concrete Research Network: LCCA/LCA study/framework for the comparison of different methods of recycling concrete.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Seyyed Ahmad Hosseini: Writing—original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Vahid Asghari: Writing—review & editing, Methodology. Xiaoyi Liu: Writing—review & editing. Shu-Chien Hsu: Writing—review & editing. Chi Sun Poon: Writing—review & editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hosseini, S.A., Asghari, V., Liu, X. et al. Cross-country life cycle assessment of construction and demolition waste recycling with evaluation of energy use, carbon emissions, and regional trade-offs. Sci Rep 15, 41377 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25387-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25387-5