Abstract

Thermal imaging, recognized for its non-contact and non-invasive properties, has been extensively used to investigate the physiological effects of emotions. While previous research has linked facial temperature changes to emotional arousal, the relationship between ear temperature and emotion remains unexplored. In this study, we acquired ear thermal imaging data and dynamic emotional ratings from 15 participants watching emotion-eliciting videos. Pixel-wise analysis revealed a negative correlation between ear temperature and emotional arousal across broad outer ear regions, including the antihelical fold, antihelix, and earlobe. These findings established ear temperature as a novel physiological marker of emotional arousal, providing new insights into thermophysiological responses to emotions. This breakthrough has important implications for affective computing, mental health monitoring, and real-time emotion recognition, expanding the potential applications of thermal imaging in emotion assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infrared thermography has emerged as a reliable and noninvasive tool for measuring physiological signals associated with human emotion by detecting the infrared radiation naturally emitted by the body1,2,3. Because it is unaffected by changes in ambient lighting, thermal imaging has found widespread applications in diverse fields, including medical diagnostics, sports science, and robotics4,5,6. The ability to monitor subtle fluctuations in skin temperature, which reflect continuous autonomic responses, is particularly advantageous for individuals with limited communication abilities and those who resist wearing sensors7,8. These temperature changes are mediated by the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system, which is activated during emotional arousal9. By inducing peripheral vasoconstriction and reducing blood flow to the skin, sympathetic activation lowers surface temperature, allowing thermal imaging data to provide a real-time window into an individual’s emotional state10.

Existing research on emotion-related thermal responses has predominantly examined full-face thermal imaging, with a particular emphasis on specific facial regions such as the nose tip11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Several studies have reported a negative correlation between nose-tip temperature and subjective arousal, a finding consistently observed in both adult and pediatric populations11,13,15,16,17. For example, Kosonogov et al.11 measured facial temperature at the nose tip and found significant negative associations with emotional arousal. Similarly, Sato et al.13 and Jian et al.16 demonstrated persistent negative correlations between nasal temperature and arousal over time. Some investigations have also examined temperature changes in the forehead, cheeks, and periorbital areas18,19, demonstrating that these regions exhibit thermal variations corresponding to emotional experiences. Collectively, these findings suggest that facial thermal imaging provides meaningful physiological signals for estimating emotional arousal.

Despite extensive research on facial regions, the ear remains an underexplored site for detecting arousal-related temperature changes. Imanishi et al.20 mapped the auricular arterial network, demonstrating how the posterior auricular, occipital, and superficial temporal arteries interconnect to supply the region. Building on this anatomical foundation, Cakmak et al.21 identified dense peri-arterial sympathetic (TH + , NPY +) terminals around auricular arteries, along with cholinergic/parasympathetic (ChAT + , VIP +) fibers—a distribution consistent with sympathetic vasoconstrictor regulation of local blood flow. The presence of peri-arterial cholinergic fibers indicates a capacity for active vasodilation, and this dual innervation suggests bidirectional vasomotor control (sympathetic constriction vs. active cholinergic vasodilation). In arousal-evoked contexts, however, the auricular response is expected to be sympathetic-dominant, resulting in vasoconstriction, reduced perfusion, and lower skin temperature21. For comparison, the nasal tip—primarily supplied by branches of the facial artery with collateral input from the ophthalmic system via the dorsal nasal artery22,23—is highly responsive to autonomic vasomotor changes but also subject to respiratory cooling, as respiration induces thermal oscillations in the nasal and nostril regions24. By contrast, the external ear is supplied by an arcade formed by the superficial temporal and posterior auricular systems, with posterior auricular dominance across much of the auricle20. This vascular architecture provides a peripheral bed in which sympathetic vasoconstriction during arousal should yield a measurable temperature decline. Accordingly, we hypothesized that ear temperature would decrease in association with increasing emotional arousal.

To test this hypothesis, we conducted an experiment in which we acquired unilateral (right) ear thermal images while participants viewed emotionally evocative clips. Following the initial viewing with thermal image acquisition, the clips were presented twice more, during which participants recalled and provided dynamic ratings of emotional valence or arousal using a slider-type affect rating dial, as described in a previous study25. We performed a pixel-based analysis to examine the relationship between ear thermal images and dynamic emotional ratings using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM)26. Originally developed for functional neuroimaging, SPM enabled systematic mapping of temperature fluctuations in the ear associated with subjective emotional ratings, while ensuring robust control of the familywise error (FWE) rate27. Based on the anatomical and physiological characteristics of sympathetic control over the ear, along with previous findings of facial thermal imaging, we predicted that the external ear would exhibit a negative association with dynamic emotional arousal. In addition, full-face thermal images were acquired and analyzed using SPM17. Finally, we exploratorily compared the results between the ear and the nose tip, the latter of which has repeatedly been linked to subjective arousal in previous studies11,13,15,16,17.

Results

Subjective ratings

Figure 1 presents the group mean time courses of the dynamic valence and arousal ratings, demonstrating that the emotional film clips elicited dynamic fluctuations in subjective emotional valence and arousal. Consistent with previous studies using dimensional emotion scales to assess emotion elicitation during film viewing13,28,29,30, emotional clips evoked higher arousal states than neutral clips.

SPM analysis of subjective–thermal associations

To examine the relationship between ear temperature and emotional arousal, a whole-ear analysis was performed using a one-sample t-test on the contrast images derived from the first-level analysis. A significant negative association was observed between ear temperature and emotional arousal (p = 0.004, cluster-level FWE-corrected) (Table 1). The significant cluster was primarily localized to the outer ear region, including the antihelical fold, antihelix, and earlobe, indicating that higher arousal levels were associated with lower temperatures in these areas (Fig. 2). No significant associations were observed for valence at the predefined thresholds.

Significant negative associations between ear temperature and emotional arousal ratings. (a) Statistical parametric map highlighting significant clusters negatively associated with arousal ratings, overlaid onto a representative standardized thermal ear image. The blue crosshair marks the activation focus at the nose tip. (b) Contrast estimate plot (with a 90% confidence interval) at the activation focus, showing the positive contrast with emotional arousal (i.e., negative values indicate negative associations). (c) Group-mean time course of temperature change at the activation focus, aligned with group-mean arousal ratings for reference. Data were sampled from a 5-mm-radius spherical region of interest across five clips presented in the order of anger, sadness, neutral, contentment, and amusement.

For comparison, we performed SPM analysis of full-face thermal images using the same general linear model pipeline and statistical thresholds as in the ear analysis (Fig. 3). Each participant’s full-face thermal images were spatially normalized to a standardized facial template, and contrast images for the arousal regressor were entered into a one-sample t-test at the group level. Significant negative associations with emotional arousal were identified in the nose tip, philtrum, and right periorbital region (Table 2; Fig. 3). Two non-significant clusters were also observed in the left forehead. No significant associations were found with valence ratings. Given our primary focus, we examined activation at the nose tip (Fig. 3) and compared it with the ear (Fig. 2). The contrast estimate for the ear was comparable to, and slightly stronger than, that observed at the nose tip.

Significant negative association between nose-tip temperature and emotional arousal. (a) Statistical parametric map showing significant clusters negatively associated with arousal ratings, overlaid on a representative standardized thermal face image. The blue crosshair indicates the activation focus at the nose tip. (b) Contrast estimate plot (90% confidence interval) at the nose-tip activation focus, showing the positive contrast with emotional arousal (i.e., negative values indicate negative associations).

Discussion

Our results revealed a significant negative association between ear temperature and emotional arousal, representing the first empirical evidence supporting this relationship. This finding is consistent with prior reports showing that the temperature of other facial regions, such as the nose tip, negatively correlates with subjective arousal ratings11,13,15,16,17. No significant association was observed between ear temperature and emotional valence, which also aligns with earlier studies11,17. The present results are in line with anatomical and physiological research indicating that the external ear, including the antihelical fold, antihelix, and earlobe, is subject to autonomic regulation21. The external ear receives peri-arterial autonomic innervation, with its blood supply primarily maintained by the posterior auricular artery and branches of the superficial temporal artery21. These vessels, governed by sympathetic vasomotor activity, regulate local blood flow and, consequently, influence skin temperature21. Since heightened emotional arousal is typically associated with increased sympathetic activation and peripheral vasoconstriction13, a reduction in ear temperature may reflect decreased blood perfusion under aroused states. While previous thermophysiological studies have established that the autonomic nervous system modulates peripheral blood flow in response to emotional stimuli, most research has focused on facial and manual regions, leaving the external ear largely unexplored11,12,13,14. Furthermore, our comparison of contrast estimates further showed that the strength of the association between ear temperature and arousal ratings was comparable to, and slightly stronger than, that of the nose tip. While the analyses differed in detail, these findings suggest that ear temperature, like nose-tip temperature, may serve as a reliable index of emotional arousal. Taken together, our results indicate that the external ear undergoes measurable physiological changes during emotional arousal, expanding the current understanding of autonomic regulation to a previously understudied peripheral site.

Our findings have practical implications for emotion sensing, as thermal imaging of the ear may offer diverse real-world applications. Compared with physiological measures such as electrodermal activity, electrocardiography, and respiration, facial infrared thermography is contactless and unobtrusive. Furthermore, compared with traditional facial infrared thermography, ear infrared thermography offers distinct advantages in contexts where face masks are worn, such as during flu seasons or in response to pollen allergies. In situations where individuals wear masks, such as during flu seasons or in response to pollen allergies, traditional face-based thermography may be hindered by partial or complete obstruction of the nose and cheeks. In contrast, the external ear typically remains exposed, making it a viable, contact-free site for continuous emotion monitoring. This characteristic is particularly valuable in clinical mental health settings, where discreet assessment of anxiety or emotional distress through ear temperature monitoring could provide clinicians with real-time, noninvasive physiological data. Additionally, compared to facial regions, which frequently undergo shape changes due to speech and expression, the external ear remains relatively stable, reducing susceptibility to motion artifacts. This stability enhances the reliability of thermal measurements and may improve the detection of subtle shifts in peripheral blood flow. Even when the face is fully visible, tracking ear temperature can serve as a complementary measure to face-focused thermography, providing an independent but equally informative index of arousal-related physiological changes.

Methodologically, our SPM-based pixel-level analysis provided a rigorous framework for detecting thermal variations in the ear, paralleling advanced analytical approaches commonly used in functional neuroimaging27. Analyses were conducted within a standardized ear coordinate system, where the vertical axis extended from the superior helix to the inferior lobule and the horizontal axis from the anterior crus of the helix to the posterior auricular margin, with the origin defined at their intersection. Pixelwise associations between temperature and arousal were estimated in SPM, and multiple comparisons were controlled using random field theory, which accounts for spatial smoothness in thermal images and ensures control of the FWE rate27.

Despite these promising findings, several limitations should be considered to enhance and extend our research. First, our study primarily involved healthy young adults, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Thermoregulatory responses can vary across different age groups and clinical populations; thus, future studies should include a more diverse sample, such as older adults or individuals with autonomic dysfunctions, to determine whether ear temperature remains a reliable marker of emotional arousal in broader populations. Second, while our regression-based approach effectively identified significant associations between ear temperature and arousal, it may not have fully captured complex patterns in temperature changes. Non-linear relationships, individual differences in thermoregulation, or interactions with other physiological factors may influence ear temperature responses in ways that traditional regression analyses might overlook. Third, we did not incorporate additional physiological measures, such as electrodermal activity, which is a well-established marker of sympathetic nervous activity. Future work should record electrodermal activity concurrently with thermal imaging and directly compare it with ear temperature using time-locked analyses. Such an approach would help establish convergent validity and quantify the incremental predictive value of ear temperature beyond skin conductance. Finally, we did not include a dedicated resting baseline block. Incorporating such a condition would facilitate interpretation of absolute temperature changes in response to visual stimuli, and we plan to address this in future work.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated a significant negative correlation between ear temperature and emotional arousal, providing the first empirical evidence that the external ear serves as a physiological marker of emotional states. Using pixel-based SPM analysis, we identified specific regions of the outer ear where temperature fluctuations track changes in arousal, expanding thermal imaging research beyond traditional face-focused approaches. While these results highlight the potential of ear thermography in emotion detection, further research is needed to improve its generalizability and robustness. Future studies should include a more diverse population to determine whether ear temperature reliably reflects arousal across different age groups and physiological conditions. Additionally, incorporating machine learning approaches could help identify more complex thermal response patterns and enhance the accuracy of emotion detection. Addressing these challenges could establish ear temperature measurement as a valuable tool for emotion research with clinical applications.

Methods

Participants

Fifteen healthy Japanese adults (8 females, 7 males; mean ± SD age: 22 ± 2.6 years) participated in this study. The required sample size was determined using an a priori power analysis with G*Power (version 3.1.9.2)31. To estimate the effect size, we reanalyzed data from a previous study that employed similar procedures to measure facial thermal images and dynamic arousal ratings13. A two-stage random-effects analysis with one-sample t-tests (one-tailed) yielded an effect size of d = 0.81 for the negative association between nose-tip ROI activity and arousal ratings. Based on this effect size, with an alpha level of 0.05 and desired power of 0.80, the analysis indicated that a minimum of 11 participants would be required. Participants were recruited through advertisements at Kyoto University and received book coupons valued at 4000 Japanese yen as compensation. All individuals were native Japanese speakers with normal or corrected-to-normal vision and no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders. Eligibility criteria included willingness to undergo both subjective and physiological assessments and no prior exposure to the emotional film clips used in the experiment. Before participation, all individuals provided written informed consent after receiving a thorough explanation of the study procedures. The study protocol was approved by the RIKEN Ethics Committee and adhered to institutional ethical guidelines and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Apparatus

The experiment was conducted using a Windows-based HP Z200 SFF computer (Hewlett-Packard Japan, Tokyo, Japan) running Presentation software (Neurobehavioral Systems, Berkeley, CA, USA) to control stimulus presentation. Visual stimuli were displayed on a 19-inch Iiyama HM903D-A monitor (Tokyo, Japan) with a resolution of 1024 × 768 pixels. Participants provided dynamic ratings using a wired optical mouse (MS116; Dell, Round Rock, TX, USA) connected to a separate Windows laptop (CF-SV8; Panasonic, Tokyo, Japan).

Thermal imaging was performed using an A655sc infrared thermal camera (FLIR Systems, Wilsonville, OR, USA) in conjunction with Research IR Max software (v. 4.40). The camera was positioned on the right side of the participants at a distance of approximately 0.77 m and captured thermal images of the right ear at a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels with a frame rate of 50 Hz. Although additional data, including full-face RGB images, were collected, these were not analyzed in the present study.

Stimuli

Five film clips were presented to elicit a range of emotional responses: Cry Freedom (highly negative, anger), The Champ (moderately negative, sadness), Abstract Shapes (neutral), Wild Birds of Japan (moderately positive, contentment), and M-1 Grand Prix The Best 2007–2009 (highly positive, amusement). These films have been validated in previous studies as effective stimuli for eliciting specific emotional states in Japanese participants13. The mean ± SD duration of the films was 175.8 ± 24 s, with individual runtimes of 157 s (anger), 172 s (sadness), 206 s (neutral), 148 s (contentment), and 196 s (amusement). Additionally, two practice films, including scenes from The Silence of the Lambs and Color Bars from Gross and Levenson13, were used to familiarize participants with the procedure. All videos were presented at a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels, corresponding to visual angles of approximately 25.5° horizontally and 11.0° vertically.

Procedure

The study took place in a soundproof, electrically shielded chamber, with an ambient temperature maintained between 23.5 °C and 24.5 °C, monitored using a TR-76Ui data logger (T&D Corp., Matsumoto, Japan). Upon arrival, participants were informed that the experiment aimed to assess subjective emotional experiences and physiological responses while viewing film clips. They were given approximately 10 min to acclimate to the room conditions before the experiment began.

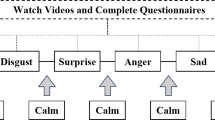

Seated 0.77 m from the monitor, participants watched the films while the thermal camera continuously recorded facial temperature changes at 30 Hz. Two practice trials were conducted to familiarize participants with the rating procedure before the five test films were presented in a pseudorandom order. As shown in Fig. 4, each trial began with a 1-s central fixation point, followed by a 10-s white screen as a pre-trial baseline. The film was then played, and after its conclusion, another 10-s white screen served as a post-trial baseline. Participants subsequently rated their overall valence and arousal using a nine-point affect grid, selecting their response by pressing the corresponding number key (1–9) on the keyboard. During the viewing phase, they were instructed to maintain focus on the screen, watch attentively, and provide ratings after each clip. The inter-trial interval was randomized between 24 and 30 s, during which the screen remained black. This interval length was chosen based on the standard 24-s window for recording skin conductance responses, a measure of sympathetic nervous system activation32. Throughout the experiment, thermal imaging data were continuously recorded, along with digital markers indicating the onset of each stimulus.

Following the initial trials, participants completed a dynamic rating session. Each film was replayed, and they were asked to recall their emotional experiences from the initial viewing, continuously rating their valence and arousal by moving the mouse. Mouse coordinates were sampled at 10 Hz. Continuous ratings were resampled to 1 Hz and aligned with the 1-Hz thermal timestamps, such that each per-second valence or arousal value corresponded to the temperature from the middle frame of that second. The valence ratings were completed first, followed by arousal ratings. This cued recall method was used to capture continuous emotional ratings, which are difficult to obtain in real time during the first viewing. Previous studies have shown that cued recall ratings align well with real-time continuous ratings for emotional film stimuli13.

Data analysis

Workflow

In this study, we used a structured workflow for analyzing ear thermal images to investigate emotional responses (Fig. 5). The process began with the acquisition of thermal image data while participants viewed emotion-eliciting stimuli. Next, the raw images underwent preprocessing steps, including normalization, conversion to NIfTI format, and smoothing. Each participant’s time series of ear temperature data was then compared with their dynamic self-reported arousal and valence ratings. Subsequently, group-level statistical analyses were performed, and contrast estimate plots with confidence intervals were generated to identify consistent patterns across participants.

Preprocessing

The first stage of preprocessing involved defining and cropping the ear region in each frame of the thermal video. We developed a semi-automated protocol that began with manually placing a fixed-size rectangular bounding box around the ear region in the initial frame. A tracking algorithm then estimated the position of this bounding box in subsequent frames. If misalignment occurred, the process was paused, and the bounding box was manually repositioned before resuming, ensuring consistent cropping of the ear region.

Once cropping was complete, we performed reference-point tracking for alignment. Specifically, markers placed at the top and bottom of the ear in the initial frame were automatically tracked throughout the video. Using the coordinates of these markers, each cropped ear image was rotated and scaled to standardize orientation and size across frames. Finally, each two-dimensional ear image (Fig. 6, left) was appended with a single unit dimension to create a three-dimensional volume, converted into NIfTI format, and optionally smoothed using a small Gaussian kernel (full-width at half-maximum, 2.3 mm; Fig. 6, right). This process prepared the data for SPM, enabling robust analyses of ear temperature fluctuations in relation to emotional arousal and valence.

SPM analysis

SPM analyses were conducted using SPM12 (revision 7487) (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm), implemented in MATLAB R2020a (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). A two-stage random-effects analysis was performed to identify significant pixel-level activations at the population level, following a standard SPM-based statistical mapping approach33.

First, a single-subject analysis was conducted using general linear modeling34, with second-by-second valence and arousal ratings included as regressors. To mitigate low-frequency noise, a high-pass filter based on a discrete cosine basis function with a cutoff period of 128 s was applied. At the second level, contrast images representing the positive and negative associations with valence or arousal from the first-stage analysis were entered into a one-sample t-test. Based on our initial hypothesis outlined in the Introduction, we first examined negative correlations with arousal ratings. Significant activation was determined using an extent threshold of p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons across the entire image, with a cluster-forming threshold of p < 0.01. Other effects were assessed using the same threshold criteria. To enhance visualization, representative thermal ear images were selected using k-medoids clustering, ensuring that the displayed activation maps accurately reflected the central tendencies of the dataset. The resulting activation patterns were overlaid onto these representative thermal ear images to highlight statistically significant regions.

Full-face analysis

Full-face analysis was performed following the procedures described by Tang et al.17. Each video was aligned to a standardized frontal facial template using UV mapping in Blender35. The first frame was manually fitted to the template, and this mapping was propagated across subsequent frames using two glabellar landmarks. Aligned frames were cropped to a fixed facial rectangle and converted into NIfTI format for SPM. Thermal images were then statistically analyzed in SPM using the same procedures described above for the ear.

Data availability

Codes used in the preprocessing are included in the supplementary information files. The thermal images are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Cruz-Albarran, I. A., Benitez-Rangel, J. P., Osornio-Rios, R. A., & Morales-Hernandez, L. A. Human emotions detection based on a smart-thermal system of thermographic images. Infrared Phys. & Technol., 81, 250–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2017.01.002 (2017)

Kylili, A., Fokaides, P. A., Christou, P., & Kalogirou, S. A. Infrared thermography (IRT) applications for building diagnostics: A review. Appl. Energy, 134, 531–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.08.005 (2014)

Lahiri, B. B., Bagavathiappan, S., Jayakumar, T., & Philip, J. Medical applications of infrared thermography: A review. Infrared Phys. & Technol., 55(4), 221–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2012.03.007 (2012)

Quesada, J. I. P., Salvador, R. P., Cacho, P., Gimeno, F., & Psikuta, A. Effects of graduated compression stockings on skin temperature after running. J. Thermal Biol., 48, 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2015.06.005 (2015)

Tanda, G. Skin temperature measurements by infrared thermography during running exercise. Exp. Thermal Fluid Sci. 71, 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2015.10.006 (2016)

Fernández-Cuevas, I., Bouzas Marins, J. C., Arnáiz Lastras, J., Carmona, P. M. G., Cano, S. P., & García-Concepción, M. Á. Classification of factors influencing the use of infrared thermography in humans: A review. Infrared Phys. & Technol., 71, 28–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2015.02.007 (2015)

Salazar-López, E., Domínguez, E., Ramos, V. J., de la Fuente, J., Meins, A., Iborra, O., & Tomás, J. M. The mental and subjective skin: Emotion, empathy, feelings and thermography. Consciousness Cognition, 34, 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2015.04.003 (2015)

Boccanfuso, L., Wang, Q., Leite, I., Li, B., Torres, C., Chen, L., … & Shic, F. A thermal emotion classifier for improved human-robot interaction. In 2016 25th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN) (pp. 718–723). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2016.7745198 (2016)

Wang, C. A., Baird, T., Huang, J., Coutinho, J. D., Brien, D. C., & Munoz, D. P. Arousal effects on pupil size, heart rate, and skin conductance in an emotional face task. Front. Neurol., 9, 1029. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.01029 (2018)

Alba, B. K., Castellani, J. W., & Charkoudian, N. Cold‐induced cutaneous vasoconstriction in humans: Function, dysfunction and the distinctly counterproductive. Exp. Physiol., 104(8), 1202–1214. https://doi.org/10.1113/EP087718 (2019)

Kosonogov, V., De Zorzi, L., Honoré, J., Martínez-Velázquez, E. S., Nandrino, J.-L., Martinez-Selva, J. M., & Sequeira, H. Facial thermal variations: A new marker of emotional arousal. PLoS One, 12(9), e0183592. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183592 (2017)

Salazar-López, E., Domínguez, E., de la Fuente, J., Meins, A., Iborra, O., Guerra, P., & Montoya, P. The mental and subjective skin: Emotion, empathy, feelings and thermography. Biol. Psychol., 104, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2015.04.003 (2015)

Sato, W., Kochiyama, T., & Yoshikawa, S. Physiological correlates of subjective emotional valence and arousal dynamics while viewing films. Biol. Psychol., 157, 107974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2020.107974 (2020)

Eom, J. S., & Sohn, J. H. Emotion recognition using facial thermal images. J. Ergon. Soc. Korea, 31(3), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.5143/JESK.2012.31.3.427 (2012)

Goulart, C., Valadão, C., Delisle-Rodriguez, D., Caldeira, E., & Bastos, T. Emotion analysis in children through facial emissivity of infrared thermal imaging. PLoS One, 14(3), e0212928. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212928 (2019)

Jian, B. L., Chen, C. L., Huang, M. W., & Yau, H. T. Emotion-specific facial activation maps based on infrared thermal image sequences. IEEE Access, 7, 48046–48052. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2908819 (2019)

Tang, B., Sato, W., Shimokawa, K., Hsu, C. T., & Kochiyama, T. Development of pixel-based facial thermal image analysis for emotion sensing. Comput. Hum. Behavior Rep. 19, 100761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2025.100761 (2025)

Love, T. J. Thermography as an indicator of blood perfusion. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 335(1), 429–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb50766.x (1980)

Mostafa, E., Farag, A., Shalaby, A., Ali, A., Gault, T., & Mahmoud, A. Long term facial parts tracking in thermal imaging for uncooperative emotion recognition. In 2013 IEEE Sixth International Conference on Biometrics: Theory, Applications and Systems (BTAS) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/BTAS.2013.6712739 (2013)

Imanishi, N., Nakajima, H., & Aiso, S. Arterial anatomy of the ear. Okajimas Folia Anatomica Japonica, 73(6), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.2535/ofaj1936.73.6_313 (1997)

Cakmak, Y. O., Cotofana, S., Jäger, C., Morawski, M., Sora, M. C., Werner, M., & Hammer, N. Peri-arterial autonomic innervation of the human ear. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 11469. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29839-z (2018)

Nguyen, J. D., & Duong, H.. Anatomy, head and neck, lateral nasal artery. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546681/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (2022)

Rohrich, R. J., Gunter, J. P., & Friedman, R. M.. Nasal tip blood supply: an anatomic study validating the safety of the transcolumellar incision in rhinoplasty. Plastic Reconstructive Surg., 95(5), 795–799. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199504001-00004 (1995)

Jiang, S., Chan, J., & Stupak, H. D.. The use of infrared thermal imaging to determine functional nasal adequacy: a pilot study. OTO open, 5(3), 2473974X211045958. https://doi.org/10.1177/2473974X211045958 (2021)

Ruef, A. M., & Levenson, R. W. Continuous measurement of emotion: The affect rating dial in Handbook of Emotion Elicitation and Assessment.(eds. Coan, JA & Allen, JJB) 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195169157.003.0018 (2007)

Friston, K. J. Statistical parametric mapping. Neuroscience databases: a practical guide, 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-1079-6_16 (2003)

Brett, M., Penny, W., & Kiebel, S. Introduction to random field theory. In Human brain function (2nd ed., pp. 867–879). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2007.09660 (2003)

Hagemann, D., Naumann, E., Maier, S., Becker, G., Lürken, A., & Bartussek, D.. The assessment of affective reactivity using films: Validity, reliability and sex differences. Personality Individual Diff., 26(4), 627–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00159-7 (1999)

Sato, W., Noguchi, M., & Yoshikawa, S.. Emotion elicitation effect of films in a Japanese sample. Soc. Behavior Personality: Int. J. 35(7), 863–874. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2007.35.7.863 (2007)

Sato, W., & Kochiyama, T.. Exploration of emotion dynamics sensing using trapezius EMG and fingertip temperature. Sensors, 22(17), 6553. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22176553 (2022)

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A.. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146 (2007)

Breska, A., Maoz, K., & Ben‐Shakhar, G.. Interstimulus intervals for skin conductance response measurement. Psychophysiology, 48(4), 437–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01084.x (2011)

Holmes, A. P., & Friston, K. J. Generalisability, random effects & population inference. NeuroImage, 7(4), S754. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-8119(18)31587-8 (1998)

Friston, K. J., Holmes, A. P., Worsley, K. J., Poline, J. P., Frith, C. D., & Frackowiak, R. S. Statistical parametric maps in functional imaging: a general linear approach. Human Brain Mapping, 2(4), 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.460020402 (1994)

Soni, L., Kaur, A., & Sharma, A. A review on different versions and interfaces of Blender software. In 2023 7th International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI) (pp. 882–887). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICOEI56765.2023.10125672 (2023)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Junyao Zhang and Masaru Usami for technical support and Professors Shin’ya Nishida and Michio Nomura for helpful advice. Our study was supported by funds from JST SPRING (JPMJSP2110).

Funding

Funding was provided by Japan Science and Technology Agency, JPMJSP2110

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: BT and WS. Performed the experiments: BT and WS. Analyzed the data: BT. Wrote the paper: BT and WS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, B., Sato, W. Ear thermal imaging for emotion sensing. Sci Rep 15, 41571 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25422-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25422-5