Abstract

In recent years, the frequent occurrence of dynamic disasters in tunnels with high stress in fault areas has greatly threatened engineering safety. The typical case – a tunnel influenced by fault slip on is taken as a research object. A series of physical simulation experiments and numerical simulations are conducted to analyze the stress evolution laws in the tunnel roof, shoulder, and coal pillar, along with the stress distribution characteristics across the working face at different excavation stages. The disaster mechanisms, the influence law of fault parameters and control measures for such tunnels are clarified. The main experiment results are as follows. The tunnel located in the hanging wall of the fault experiences a more pronounced increase in stress. Additionally, the closer the tunnel is to the fault plane in the hanging wall, the higher the stresses in the roof, shoulders, and coal pillar sides. For example, the stress at measurement point Jβ−3 in the β measurement section is 63.4% higher than that at point Jα−3 in the α measurement section. Moreover, the surrounding rock at different locations of the tunnel is more severely affected by the fault deeper inside, while the shallow parts experience less influence. Meanwhile, the pressure relief effect by the artificial pre-splitting for high-stress tunnels is proven by the established quantitative evaluation indicators for stress increase and decrease. Among them, the application of the new technology results in a maximum reduction of 145.4% in stress change rate. Through this study, a preliminary measure for controlling the surrounding rock of high-stress tunnels in fault areas is proposed, which can provide a reference for the control of similar tunnels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increasing demand for energy and the intensification of mining activities, shallow resources are gradually depleting, and coal mining is progressively extending to greater depths1,2,3. Deep mining environments are facing increasingly complex geological environments, including high ground stress, fault zones, and strong mining disturbances4,5,6. Among them, the tunnels in the deep fault zone are under the influence of the superposition of deep buried high stress and fault structural stress, and the surrounding rock stress is at a very high value7,8,9. At this time, with the emergence of coal mining space, the fault surface near the tunnel is equipped with sliding space, which makes fault sliding extremely prone to occur, and may trigger such tunnel dynamic disaster incidents10,11.

Complex geological conditions, such as faults, disrupt the continuity and integrity of rock layers12, leading to stress concentration near these faults. Numerous scholars have conducted a series of studies using different research methods. In terms of numerical simulation, Shan et al.13 investigated the asymmetric deformation of tunnels under the influence of geological structures and mining activities using numerical simulation by FLAC3D software, analyzing the distribution patterns of deviatoric stress and plastic zones under different distances from the fault plane. Jiang et al.14 used FLAC3D software to simulate and analyze the stress evolution characteristics of the working face in the hanging wall, revealing the formation of high stress concentration zones in the fault pillar and ahead of the working face. Sun et al.15 used FLAC3D software to study the stress distribution law of surrounding rock in deep fault zone tunnels, and analyzed the rock failure mode of such tunnels. Thus, it can be seen that the existing research primarily employs numerical simulation and theoretical analysis to examine stress variation characteristics of working faces and tunnel surrounding rock under fault conditions. However, current research methods have limitations: theoretical analysis and numerical simulation results lack sufficient validation. Physical model tests, which accurately reflect the spatial relationships between geological structures and engineering layouts, serve as an effective means to replicate field conditions for holistic research, addressing the shortcomings of the aforementioned methods16,17,18.

In terms of physical model experiment, Ma et al.19 conducted physical similarity experiments (4.2 × 1.5 × 0.25 m model body size) on two fault structures to study the distribution characteristics of mining-induced stress under fault influence. The results showed that fault slip and dislocation caused by coal mining can lead to rock impact and fragmentation, significantly affecting the behavior of mine pressure. Wang et al.20 conducted a physical model experiment (3.0 × 1.3 × 0.6 m model body size) to determine the main factors that the deformation and failure of fault zone tunnel and reveal the underlying mechanisms. The results show that when crossing a fault, the high static load formed by the coupling of mining stress and fault pillar stress induces mining stress-type fault activation. It can be seen that, at present, the simulation of tunnels in fault structures during the entire mining process is mainly based on two-dimensional plane models. This physical simulation is relatively reliable for studying the stress impact of faults on a certain position of the tunnel, but it cannot study the stress impact of faults on the tunnel as the working face continues to be mined.

To address the issue of stress concentration in the surrounding rock, a pressure relief method is needed to effectively reduce rock mass stress and release energy. Many scholars have conducted extensive research on pressure relief techniques for tunnel surrounding rock. Zhang et al.21 carried out laboratory and field tests on borehole pressure relief, optimizing borehole parameters to effectively reduce stress concentration in coal seams. Cui et al.22 used numerical simulations to study the angle of pressure relief boreholes, proposing a calculation formula for borehole angle design and validating it through typical engineering cases. Chen et al.23 conducted numerical experiments on coal seam water injection ahead of the working face, demonstrating a significant reduction in peak stress within the coal mass, thereby verifying the effectiveness of water injection for pressure relief. Kang et al.24 performed numerical and field tests on hydraulic fracturing for pressure relief in deep mine tunnels, effectively reducing stress in roof rock masses. To achieve precise directional roof cutting, He et al. proposed a method of directional pre-splitting and cutting for surrounding rock pressure relief25. This method exploits the compressive-weakening and tensile-failure characteristics of rock masses, inducing controlled tensile fractures along predetermined directions to form pre-split surfaces. By cutting the roof at designed locations and directions, the roof collapses along the pre-split fractures at the intended height, severing stress transmission between the tunnel roof and the goaf roof, thereby reducing tunnel surrounding rock stress and achieving effective control. This artificial directional pre-splitting technology provides a new idea for the control of tunnels in deep fault zones in principle. However, its control advantage over this type of tunnel needs further verification, and the impact of core technical parameters on its control effect needs to be clarified.

Based on this, this paper focuses on typical fault-induced dynamic disaster tunnels under high stress, employing a comprehensive method combining large scale 3D physical model tests and numerical simulations. The study investigates disaster mechanisms and control measures for mining tunnels in high-stress fault zones, comparing the variation and distribution patterns of mining pressure under different influencing factors. Numerical comparative tests are conducted on high-stress tunnels in fault zones under various pressure relief methods to clarify disaster mechanisms induced by faults and mining, as well as the influence pattern and control mechanisms of artificial pre-splitting for pressure relief. It could provide a methodological basis for surrounding rock control in high-stress tunnels within fault zones.

The typical tunnel with high stress in fault zones

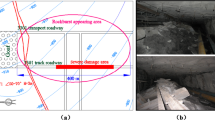

A dynamic disaster accident occurred in the fully mechanized top-coal caving mining face of a coal mine in China, located in a typical high-stress tunnel within a fault zone. This chapter introduces the basic parameters of the working face, tunnel, and fault in this area, as well as the on-site damage conditions, providing a parameter basis for subsequent numerical simulations and physical model tests.

Basic parameters

The maximum burial depth of the accident-prone working face W1 in this mine exceeds 1000 m. Its adjacent W2 working face has already been mined out, leaving a 5 m pillar between the two faces. The fully mechanized top-coal caving technology is adopted in the W1 working face. This method mainly includes two parts: one-time coal mining by the coal cutter and self weight collapse of the top coal. The average coal seam thickness is 9.2 m, the mining height is 3.6 m and the top coal caving thickness is 5.6 m. The immediate roof is siltstone with the thickness of 3.0 m, a main roof of about 17.0 m of fine sandstone, and an immediate floor of roughly 5.0 m of fine sandstone, as shown in Fig. 1. The physical and mechanical parameters of the main coal and rock masses are listed in Table 1.

There is a fault in the working face where the accident occurred, posing a safety hazard. The fault passes through the test tunnel, but the location passed through is at a certain distance in front of the accident area of the tunnel. It has a throw of 0 ~ 15 m (average value of 12 m), a dip angle of 70 degrees, and a dip direction of North West. As shown in Fig. 2, the original measurement section of the tunnel is rectangular, with a width of 4.8 m and a height of 4.0 m. The tunnel is supported by a combination of anchor cables and bolts. The roof is reinforced with cables of 22 mm diameter and 6.3 m length, as well as cables of 22 mm diameter and 3.8 m length. The sidewalls are supported by cables of 22 mm diameter and 3.8 m length, along with rock bolts of 22 mm diameter and 2.5 m length. The spacing between bolts and cable bolts is 900 × 1000 mm. Detailed tunnel support parameters are shown in Fig. 2.

Failure conditions of the surrounding rock in the tunnel

Under the aforementioned tunnel support conditions, a dynamic impact accident occurred in the upper tunnel of the W1 working face, affecting a range of 420 m, as shown in Fig. 1. After the incident, measurement sectional shape sketches are conducted at four typical locations in the tunnel, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The tunnel, after severe contraction deformation, has a height ranging from 1.8 to 3.2 m and a width between 2.3 and 3.8 m. This indicates roof-to-floor deformation of 0.8 to 2.2 m and sidewall deformation of 1.0 to 2.5 m.

Preliminary analysis suggests the following causes. The tunnel where the accident occurred is deeply buried, resulting in high internal stress in the surrounding rock. More importantly, the main fault in this area intersects obliquely with the W1 working face, forming a triangular zone. As the working face advances, the area of this triangular zone gradually decreases, leading to extremely complex stress variations in the tunnel region, compounded by superimposed stress disturbances from the working face mining activities. These factors collectively contribute to the occurrence of the dynamic impact accident.

Further in-depth research is required to investigate the influence of specific fault structures on the disaster mechanisms of high-stress tunnels during mining, the impact patterns of fault parameters, and appropriate control strategies.

Physical simulation experiment on the catastrophic failure of tunnels under high stress in a fault zone

To investigate the stress evolution patterns of the aforementioned high stress tunnels and working faces in fault zones, and to clarify the relationship between tunnel deformation/failure and surrounding rock stress during mining operations, a physical simulation experiment study on catastrophic failure of tunnels under high stress in fault zones is conducted using a coal mining physical simulation test apparatus, as shown in Fig. 3. The simulation area selected for this experiment is taken from the accident area and does not reach the location where the fault passes through the tunnel.

Overall plan design in physical simulation

(1) Similar scale parameters

Based on the dimensions of the physical simulation test device and the simulated object, the geometric similarity ratio is determined to be 1/80, and the stress similarity ratio is set at 1/96 (with a unit weight similarity ratio of 1/1.2). According to the physical simulation similarity theory, the similarity ratios for elastic modulus and cohesion are equal to the stress similarity ratio, while the similarity ratios for strain, internal friction angle, and Poisson’s ratio are all 1.

After conversion using the similarity ratios, the length of the W1 working face in the model is 3.25 m, simulating an actual working face length of 260 m. The measurement sectional dimensions of the tunnel in the model are 60 mm in width and 50 mm in height, simulating an actual tunnel measurement section of 4.8 m in width and 4.0 m in height. The simulated fault is set a throw of 15 mm (corresponding to 12 m on site). Simulate rock strata on both sides of the fault and create a set throw during the laying process. The fault plane is simulated by laying mica sheets, with a thickness of 10 mm. The laying direction and angle are set according to the on-site parameters.

(2) Measurement plan

The stress measurement plan for this experiment is as follows. Inside the model, two measurement sections, α and β, are set up along the simulated working face excavation direction, located 0.75 m and 2.25 m from the front surface of the model, respectively. In each measurement section, the stress measurement is conducted at key locations, including the tunnel roof, shoulder, coal pillar, and working face. The specific layout of measurement points is as follows. Tunnel roof measurement points are labeled Dm−n. Tunnel shoulder measurement points are labeled Jm−n. Coal pillar measurement points are labeled Zm−n. Working face measurement points are labeled Gm−n. In the above symbols, m denotes the measurement section, m = α ~ β; and n represents the n measurement point. Among them, the α measurement section is illustrated in Fig. 4(a), and the β measurement section is illustrated in Fig. 4(b). The distances between each measurement point are marked on this figure.

(3) Specific model construction plan

After completing the model filling and installing the measurement points, boundary loading forces are applied to the model in both the vertical and horizontal directions. Based on the aforementioned stress similarity ratio, the simulated vertical in-situ stress at the W1 working face reaches 0.250 MPa, while the horizontal in-situ stress reaches 0.469 MPa. After maintaining the pressure for 24 h, the model excavation commences, which involves four construction steps (Fig. 5), namely: (a) construction of W2 working face, excavation step spacing of 0.2 m, a total of 15 steps; (b) Construction of lower tunnel, excavation step spacing of 0.6 m, a total of 5 steps; (c) Construction of upper tunnel, excavation step spacing of 0.6 m, a total of 5 steps; (d) Construction of W1 working face, excavation step spacing of 0.1 m, a total of 30 steps.

The excavation for four step model construction. (a) Schematic of excavation plan, (Made by SolidWorks 2015) https://help.solidworks.com/2015/chinese/solidworks/install_guide/t_initiating_sw_installation.htm, (b) Four step excavation site photos.

Analysis of physical simulation results

The stress evolution laws in the tunnel roof, shoulder, and coal pillar during the entire Step four process are analyzed, along with the stress distribution characteristics across the working face at different excavation stages.

Stress evolution analysis of the tunnel roof

During the working face excavation (Step four), the stresses at various measurement points on the upper tunnel roof in α and β measurement sections are continuously monitored. The stress evolution curves of the tunnel roof in both measurement sections are plotted in Fig. 6.

The specific analysis of the data pattern in Fig. 6 is as follows.

(1) The α measurement section

As the working face advances, the stress at each measurement point in the tunnel roof increases to a peak. The peak stresses at Dα−1, Dα−2, Dα−3, and Dα−4 are 0.215 MPa, 0.482 MPa, 0.439 MPa, and 0.372 MPa, respectively. The original rock stress is 0.250 MPa, indicating that Dα−1 is in a deformation pressure-relief zone with stress lower than the original rock stress, while Dα−2, Dα−3, and Dα−4 are in a stress-increasing zone with stresses higher than the original rock stress. As mining progresses beyond the measurement section α, the roof stresses at all measurement points drop sharply. This suggests that the tunnel roof collapses along with the overlying strata of the goaf, leading to stress reduction. The post-collapse stresses at all roof measurement points are significantly lower than the original rock stress.

(2) The β measurement section

When the working face is 1500 mm away from measurement section β, the stresses at the roof measurement points begin to rise. This indicates that the advance influence range of such tunnels is approximately 0 ~ 1500 mm, which translates to an on-site advance influence range of 120 m, consistent with field engineering data. The peak stresses at Dβ−1, Dβ−3, and Dβ−4 are 0.239 MPa, 0.517 MPa, and 0.551 MPa, respectively. Due to sensor failure, no valid data are obtained for Dα−2. Similar to the results from the α measurement section, the stress at the shallowest measurement point, Dβ−1, is lower than the original rock stress, indicating a pressure-relief zone. Additionally, once mining advances beyond the β measurement section, the abrupt stress drop at all roof measurement points follows the same pattern as in the α measurement section.

According to the measurement plan, compared to measurement section α, the main fault at measurement section β is closer to the study object—the upper tunnel. Comparing the peak stress data from the two sections, the peak stresses at Dβ−1, Dβ−3, and Dβ−4 increase by 10.0%, 15.1%, and 32.5%, respectively, relative to Dα−1, Dα−3, and Dα−4. This demonstrates that the closer the tunnel is to the fault during mining, the higher the internal roof stress and the greater the risk of dynamic disasters. Furthermore, two additional effects are observed: ① The intact deep surrounding rock in the tunnel roof is more significantly affected by the fault, while the shallow pressure-relief zone is less influenced. ② Due to the fault’s proximity to the tunnel, the peak internal roof stress shifts deeper (from Dα−2 to Dβ−4).

Analysis of stress evolution in tunnel shoulder zones

As the working face advances (Step Four), continuous measurement is conducted on the stress at various measurement points in the shoulder zones of the upper tunnel at measurement sections α and β. The stress evolution patterns in the tunnel shoulders at these two sections are illustrated in Fig. 7.

The specific analysis of the data pattern in Fig. 7 is as follows.

(1) The α measurement section

As the working face advances, the stress at each measurement point in the tunnel shoulders increases to its peak value. The peak stresses at Dα−1, Jα−1, and Jα−2 are 0.215 MPa, 0.662 MPa, and 0.450 MPa, respectively, with all peak locations situated at the α measurement section. The peak stresses at Jα−1 and Jα−2 reach 2.65 and 1.80 times the original rock stress, respectively. This indicates that the maximum stress in the tunnel shoulders occurs at the middle measurement point (Jα−1), suggesting an overall “increase-then-decrease-to-stabilization” trend in shoulder stress distribution. Once mining progresses beyond the α measurement section, the stresses at all shoulder measurement points drop sharply, following a pattern consistent with the roof stress evolution (not repeated here for brevity).

(2) The β measurement section

When the working face approaches within 1500 mm of the β measurement section, the stresses at shoulder measurement points Jβ−1 and Jβ−2 begin to exhibit an increasing trend. This observation confirms that the advanced influence range of this type of tunnel is approximately 0–1500 mm, which corresponds to an actual mining-induced influence range of 120 m in field conditions - a finding consistent with the roof behavior pattern. The peak stress recorded at Dβ−1, Jβ−1, and Jβ−2 is 0.239 MPa, 1.410 MPa, and 1.230 MPa, respectively. (The stress pattern at Dβ−1 has been previously discussed in the roof section analysis.) Notably, the peak stresses at Jβ−1 and Jβ−2 reach 5.64 and 4.92 times the original in-situ stress level, demonstrating significant stress amplification in the shoulder regions under the combined effects of fault proximity and mining activities.

Comparing the peak stress data at the shoulder sections of the two measurement sections, the peak stresses at points Dβ−1, Jβ−2, and Jβ−3 increase by 10.0%, 53.0%, and 63.4%, respectively, relative to measurement points Dα−1, Jα−2, and Jα−3. Similarly, the closer the tunnel is to the fault during mining, the higher the internal stress in its shoulder section. Compared to the internal stress in the roof surrounding rock, the stress increase in the shoulder section is more significant, making it a more critical factor in triggering dynamic impact disasters in tunnels within high-stress fault zones.

Analysis of stress evolution law inside the coal pillar

As the working face advances (Step four), continuous measurement is conducted on the internal stress of measurement points within the coal pillar of the upper tunnel in measurement sections α and β. The stress evolution patterns inside the coal mass of the tunnels in both measurement sections are plotted, as shown in Fig. 8.

Compared with the α measurement section, the main fault in the β measurement section is located closer to the coal pillar on the upper tunnel side. Analysis of Fig. 8 reveals the following. When the working face advances to the α measurement section, the internal stress in the coal mass reaches 0.691 MPa, 2.8 times the in-situ stress. When the working face reaches the β measurement section, the internal stress increases to 0.717 MPa, 2.9 times the in-situ stress. The results indicate that the internal stress of the coal pillar rises significantly under mining-induced disturbances. The proximity of the fault further amplifies this stress increase, leading to a higher stress concentration.

Analysis of stress distribution patterns in the working face

Taking measurement points above the roof of the working face in the α and β measurement sections as the research subjects, the stress distribution patterns across the entire working face are analyzed for four distinct stages: ① After Step one (W2 Working face excavation completion); ② After Step three (Upper tunnel excavation completion); ③ When Step four reaches the measurement section (Excavation to measurement section); ④ After Step four (W1 Working face excavation completion). The stress distribution results are illustrated in Fig. 9. The stress measurement points include Gi−1 to Gi−13 and Di−2, where i represents α and β (refer to Fig. 4 for specific locations).

Analysis of Fig. 9 reveals that during the three stages—W2 Working face excavating end, upper tunnel excavating end, and excavating to measurement section of W1 Working face—the stress at the upper tunnel is significantly higher than that at the lower tunnel. However, during the W1 working face excavating end stage, the surrounding rock of both tunnels is in a collapsed state, with stresses lower than the in-situ stress, and thus no detailed analysis is conducted for this stage.

The specific analysis for the three stages—W2 Working face excavating end, upper tunnel excavating end, and excavating to measurement section—is as follows.

(1) Stress analysis on both sides of the fault zone in different stages

1) The α measurement section.

-

(i)

During the W2 Working face excavating end and upper tunnel excavating end stages, the stresses on both sides of the fault increase from 0.257 MPa and 0.258 MPa to 0.265 MPa and 0.269 MPa, respectively (Fig. 9a). The stress difference between the left and right sides of the fault is minimal. This is because the W2 Working face is far from the fault, so its excavation has no impact on the fault zone. Similarly, the excavation of the upper tunnel, being small in scale and not intersecting the fault, also does not affect the fault zone.

-

(ii)

During the excavating to the α measurement section stage, the stress on both sides of the fault rises from 0.341 MPa to 0.373 MPa, showing a more pronounced difference compared to the previous two stages.

2) The β measurement section.

During the W2 Working face excavating end and Upper tunnel excavating end stages, the stresses on both sides of the fault increase from 0.251 MPa and 0.263 MPa to 0.259 MPa and 0.267 MPa, respectively (Fig. 9b). This trend is consistent with that observed in the α measurement section and will not be elaborated further. During the excavating to measurement section α stage, the stress on both sides of the fault rises from 0.572 MPa to 0.664 MPa, again showing a significant difference compared to the previous stages.

The data from these two measurement sections indicate that the mining of adjacent working faces and tunnel excavation have a minor impact on the stress distribution around the fault. However, the main fault significantly influences the stress distribution in the surrounding rock after the excavation of the W1 Working face, with higher stress observed on the hanging wall. This also corroborates the higher stress observed in the upper tunnel located on the hanging wall.

(2) Comparative analysis of stress peaks near the upper tunnel at different stages

1) The α measurement section.

At the three stages—W2 working face excavation completion, upper tunnel excavation completion, and excavation to the measurement section of W1 working face—the stress peaks near the upper tunnel were 0.540 MPa, 0.542 MPa, and 0.661 MPa, respectively. It can be observed that the excavation of adjacent working faces and tunnels has a minor impact on the stress of the upper tunnel. In contrast, the mining of the current working face significantly influences the stress of the upper tunnel.

2) The β measurement section.

At the three stages—W2 working face excavation completion, upper tunnel excavation completion, and excavation to the measurement section—the stress peaks near the upper tunnel are 0.472 MPa, 0.503 MPa, and 1.143 MPa, respectively. The excavation of adjacent working faces and tunnels has a limited effect on the stress of the upper tunnel. However, due to the fault being closer to the upper tunnel, its influence on the tunnel is more pronounced, compounded by the mining impact of the current working face. These factors cause a sharp rise in the surrounding rock stress of the upper tunnel, reaching up to 4.6 times the original rock stress, posing a significant risk for dynamic impact disasters.

Combining the results of the physical simulation experiments in Chap. 3, the drastic increase in stress in the overlying strata, roof, shoulder, and coal pillar areas of the tunnel can be attributed to two main factors: mining influence and fault structure influence. The closer the fault is to the tunnel, the more pronounced its effect, with a significantly greater impact on tunnels within the hanging wall strata compared to those in the footwall. This is the primary cause of dynamic impact accidents in high-stress tunnels within fault zones, as studied in this paper. Building on this, further research is needed to explore how specific fault parameters affect the upper tunnel and how to prevent and control such accidents.

Numerical simulation study on fault influence mechanisms and artificial pre-splitting control

Based on physical simulation experiments, using the internal stress of the coal pillar in the upper tunnel as a representative of tunnel surrounding rock stress, this chapter investigates the influence of different fault parameters (fault tendency, fault angle) on the stress distribution around the tunnel. Additionally, it explores the control effect of artificial pre-splitting pressure relief on such tunnels. To address these research objectives, this chapter sequentially conducts numerical simulations on the influence mechanisms of different fault parameters and the artificial pre-splitting control of high-stress tunnels near faults.

Numerical simulation of the influence of fault parameters on tunnels

To clarify the influence of fault parameters on tunnel surrounding rock stress, numerical comparative experiments under different fault parameters are conducted based on physical simulation tests, with the upper tunnel of the W1 working face as the research subject.

Specific simulation plan

The experiment is divided into two parts, including fault tendency and fault angle, numbered I− i and II− j. The specific parameters are shown in Table 2.

(1) In terms of fault tendency (I− i): The main fault tendency on site is North West 70 °, and it is set as the I− 3 plan; In addition, I− 1 is North West 60 °, I− 2 is North West 65 °, I− 4 is North West 75 °, and I− 5 is North West 80 °.

(2) In terms of fault angle (II− j): the main fault angle on site is 70 °, which is set as the II− 3 plan; In addition, II− 1 is 60 °, II− 2 is 65 °, II− 4 is 75 °, and II− 5 is 80 °. The parameters of other working faces, faults, and tunnels are consistent with those on site.

Parameters of the model body

Based on field conditions and physical simulations, a numerical calculation model is established using FLAC 3D. The model measures 450 m in length, 250 m in width, and 200 m in height. The mechanical parameters of each rock layer in the model are assigned according to Table 1, employing the Mohr-Coulomb constitutive model. The bottom boundary of the model is fixed in both vertical and horizontal directions, while the side boundaries are fixed horizontally. The top boundary is set as a stress boundary, with the applied value representing the overburden rock weight (not shown). The model parameters and the stress distribution within the coal seam are illustrated in Fig. 10. About simulated fault parameter, the shear stiffness is set to 109 Pa, the normal stiffness is set to 2 × 109 Pa, the cohesion is set to 5 × 103 N, and the friction angle is set to 17.5°. The excavation plan of the numerical model is consistent with that of the physical simulation tests.

Since the physical simulation has already conducted a detailed analysis of the stresses in different sections of the tunnel, the numerical simulation focuses only on the coal pillar area as a representative case to study the influence of different fault parameters on tunnel stresses. Specifically, five stress measurement points (labeled Z1 to Z5) are arranged within the 5 m-wide coal pillar at 1.0 m intervals.

To better compare and analyze the stress variation patterns in the surrounding rock of the tunnel under different plans and the degree of fault influence, a quantitative evaluation index called the “coal pillar stress increasing rate (\(\:{\eta}_{{\text{Z}}_{\text{i}\text{-j-l}}}\))” is established for comprehensive assessment. The coal pillar stress increasing rate (\(\:{\eta}_{{\text{Z}}_{\text{i}\text{-j-l}}}\)) represents the percentage increase in tunnel coal pillar stress compared to the original rock stress, calculated as follows:

Where:

\(\:{\eta}_{{\text{Z}}_{\text{i}\text{-j-l}}}\)—The coal pillar stress increasing rate at measurement point l in plan i-j, representing the degree of stress increase at point l compared to the in-situ rock stress in plan i-j. A higher \(\:{\eta}_{{\text{Z}}_{\text{i}\text{-j-l}}}\) indicates a more pronounced influence of the fault on the coal pillar. Here, i denotes the type of plan (i = I ~ II), and j represents the sub-plan under the main category (j = 1 ~ 5). For example, \(\:{\eta}_{{\text{Z}}_{\text{I-1-1}}}\) refers to the stress increasing rate at measurement point l in plan I-1, in %.

\(\:{Z}_{\text{i-j-}\text{ini}}\)—In-situ rock stress at the coal pillar in plan i-j, in MPa.

\(\:{Z}_{\text{i-j-l}}\)—Stress at measurement point l of the coal pillar in plan i-j, in MPa.

Analysis of test results for different fault parameter plans

When the working face advances to the measurement section, the stress distribution at each measurement point of the tunnel coal pillar under different fault tendencies/angles is shown in Figs. 11(a) and 12(a), respectively. The quantitative evaluation indices of surrounding rock stress at the peak stress measurement points under the two conditions are presented in Figs. 11(b) and 12(b), respectively.

The specific analysis of the data pattern in Figs. 11 ~ 12 is as follows.

(1) In the fault tendency plans, the stress within the tunnel coal pillar exhibits a single-peak distribution characterized by “high in the middle and low on both sides,” with the peak stress located at the center of the coal pillar. The peak stresses for each plan are 54.11 MPa, 53.82 MPa, 53.15 MPa, 52.86 MPa, and 51.90 MPa, with coal pillar stress increasing rates of 125.5%, 124.3%, 121.5%, 120.3%, and 116.3%, respectively. As the fault tendency increases, the peak stress within the coal pillar shows an upward trend. This is because a larger fault tendency brings the fault closer to the upper tunnel at the measurement section. This further confirms that the closer the fault is to the upper tunnel, the greater the peak stress within the coal pillar.

(2) In the fault angle plans, the stress within the tunnel coal pillar also displays a single-peak distribution of “high in the middle and low on both sides,” with the peak stress located at the center of the coal pillar. The peak stresses for each plan are 53.95 MPa, 54.36 MPa, 53.21 MPa, 52.93 MPa, and 51.60 MPa, with coal pillar stress increasing rates of 124.8%, 126.5%, 121.7%, 120.5%, and 115.0%, respectively. The influence of fault angle on coal pillar stress differs from that of fault tendency. When the fault angle is 65°, the peak stress within the coal pillar reaches its maximum. Within the range of 65°~80°, a negative correlation is observed between the fault angle and the peak stress in the coal pillar.

The above summarizes the influence of fault parameters on the stress distribution in the surrounding rock of the tunnel. However, further research is still needed to determine how to prevent and control dynamic disasters in tunnels subjected to high stress in fault zones.

Numerical simulation of artificial pre-splitting control in fault zone tunnels

Using the widely adopted artificial pre-splitting technology, this chapter investigates the surrounding rock control during the excavation of high-stress tunnels in fault zones. This technology utilizes the high compressive strength and low tensile strength of rocks to achieve. Specifically, using a directional pre-splitting device, a concentrated blasting force is generated in the set direction of each blast hole, and adjacent blast holes are interconnected through cracks. Therefore, an artificial pre-splitting surface with a set direction is formed, as shown in Fig. 13. The numerical model remains consistent with the one established in Sect. 4.1, with the addition of an artificial pre-splitting simulation.

Specific simulation plan

Based on the I− 3 model from Sect. 4.1 (aligned with field conditions), simulations of artificial pre-splitting roof cutting are conducted. The simulations primarily focus on two aspects: pre-splitting height (height of cutting) and pre-splitting angle (angle of cutting), labeled as III− i and IV− j, respectively. The specific plan parameters are listed in Table 3.

To better compare and analyze the effect of artificial pre-splitting on reducing the stress of surrounding rock in fault area tunnels under different plans, a quantitative evaluation index of coal pillar stress change rate (\(\:{\delta\:}_{{\text{Z}}_{\text{i}\text{-j}}}\)) is established to comprehensively evaluate and analyze the stress of surrounding rock. The stress change rate of coal pillars (\(\:{\delta\:}_{{\text{Z}}_{\text{i}\text{-j}}}\)) refers to the percentage decrease in the average stress of coal pillars in the tunnel compared to the average stress of coal pillars in the uncut tunnel. The calculation formula is as follows.

Where:

\(\:{\delta\:}_{{\text{Z}}_{\text{i}\text{-j}}}\)—The stress change rate of the tunnel coal pillars in the i-j plan, %. The higher the δ (\(\:{\delta\:}_{{\text{Z}}_{\text{i}\text{-j}}}\)), the more significant the impact of roof cutting and pressure relief on the tunnel coal pillars. Among them, i represents different types of plan numbers, i = III-IV, j represents sub plans under the main category plan, j = 1 ~ 5.

\(\:{\stackrel{-}{Z}}_{\text{I-3}}\)—The average stress of the tunnel coal pillars in the I− 3 plan, MPa. The average stress of coal pillars in tunnels that have not been artificially pre cracked.

\(\:{\stackrel{-}{Z}}_{\text{i-j}}\)—The average stress of the tunnel coal pillar in the i-j plan, MPa.

Analysis of test results for different control parameter plans

When the mining face reaches the measurement section, the stress distribution of different artificial pre-splitting parameters (height of cutting, angle of cutting) at each measurement point of the coal pillar is shown in Fig. 14 (a) and Fig. 15 (a), respectively. Among them, the quantitative evaluation indicators of the surrounding rock stress at the measurement points corresponding to the peak stress of the coal pillar under the two conditions are shown in Fig. 14 (b) and Fig. 15 (b), respectively.

The specific analysis of the data pattern in Figs. 14 ~ 15 is as follows.

(1) In the artificial pre-splitting height plans, the stress within the tunnel coal pillar exhibits a single-peak distribution characterized by “high in the middle and low on both sides,” with the peak located at the center of the coal pillar. Compared to tunnels without artificial pre-splitting, the internal stress of the coal pillar in each pre-splitting plan is reduced to varying degrees. The stress change rates in the coal pillar for Plans III− 1 to III− 5 are 118.9%, 113.6%, 102.5%, 97.5%, and 91.9%, respectively. This demonstrates that the artificial pre-splitting technique effectively reduces the surrounding rock stress of the tunnel. The optimal artificial pre-splitting height is 15 m (Plan III− 1), which provides the best pressure relief effect for tunnels in high-stress fault zones.

(2) In the artificial pre-splitting angle plans, the internal stress distribution of the tunnel coal pillar is generally consistent with that of the pre-splitting height plans. Among Plans IV− 1 to IV− 3, the internal stresses of the coal pillars show little variation, with stress change rates ranging from 102.5% to 145.4%. However, in Plans IV− 4 to IV− 5, the internal stress of the coal pillars increases significantly, and the stress change rates drop noticeably to 37.4%~42.0%. This indicates that when the artificial pre-splitting angle is within 0 ~ 10°, the internal stress of the coal pillar is significantly lower than when the angle is 15 ~ 20°. Therefore, the optimal angle should be selected within the 0 ~ 10° range, with the specific value determined based on the engineering requirements for blasting and pre-splitting on-site.

The above data demonstrate that artificial pre-splitting roof cutting enhances rock strata caving, reduces the rotation of overlying strata in the fault zone above the tunnel, alleviates stress concentration to some extent, and lowers the risk of dynamic impact disasters.

Conclusion

A typical case study of high-stress tunnels within fault zones is conducted to explore the factors of and control measures of fault slip induced disasters through a series of experiments. The physical simulation experiments of surrounding rock failure in high-stress tunnels within fault zones are carried out. The disaster law of such tunnels is clarified. Furthermore, two types of numerical simulations are performed to investigate the influence of fault parameters and control measures for such tunnels is also carried out. The impact patterns of different fault parameters on working face stress, as well as the pressure relief effects of high-stress tunnels under various artificial pre-splitting parameters, are revealed. The specific conclusions are as follows.

(1) The physical simulation experiment result shows that after mining through a fault—i.e., when the fault has slip space—the influence of the fault on high-stress tunnels becomes significant. Tunnels located in the hanging wall of the fault experience a more pronounced increase in stress, and the sharp stress increase of such tunnels in the fault hanging wall caused by the fault and mining activities is the internal factor triggering dynamic disasters. Additionally, the closer the tunnel is to the fault plane in the hanging wall, the higher the stresses in the roof, shoulders, and coal pillar sides. For instance, the stress at measurement point Jβ−3 in the β measurement section is 63.4% higher than that at point Jα−3 in the α measurement section. Moreover, the deeper surrounding rock of the tunnel is more severely affected by the fault, while the shallow parts experience less influence.

(2) Two types of numerical simulations results show that when the fault angle ranges between 65° and 80°, there is a negative correlation between the fault angle and the peak stress in the coal pillar, and the peak stress inside the coal pillar tends to rise with the fault tendency increasing. Additionally, artificial pre-splitting of the roof enhances the broken expansion degree of the caving rock strata, reduces the rotation of overlying strata above the tunnel in the fault zone, alleviates stress concentration to some extent, and lowers the risk of dynamic impact disasters. Regarding the selection of pre-splitting control parameters, the case in this study serves as an example. The optimal artificial pre-splitting height is 15 m, and the optimal pre-splitting angle is in a range of 0 ~ 10°, which provides the best pressure relief effect for high-stress tunnels in fault zones.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

He Manchao, W. Rock dynamics in deep mining[J]. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 33 (09), 1065–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2023.07.006 (2023).

Kang Hongpu, G., Fuqiang, X., Gang, R. & Huaiwei Mechanical behaviors of coal measures and ground control technologies for china’s deep coal mines–A review[J]. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 15 (01), 37–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2022.11.004 (2023).

Yu Bingbing, Y., Renshu, Z., Jinjing, W. & Yanbing A new method for multi-dimensional impact risk quantization and pressure-relief evaluation of deep rockburst mines based on FCM-EWM[J]. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 161, 106609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2025.106609 (2025).

Zhang Jicheng, L. et al. Dual-scale insights of two-phase flow in inter-cleats based on microfluidics: interface jumps and energy dissipation[J]. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 35, 451–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2025.01.010 (2025).

Jiang Zhenhua, Z., Jicheng, Y. & Lijun, L. Coordinated control of pressure relief and energy absorption support of deep mining roadway[J]. Phys. Fluids. 37 (04), 047138. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0267108 (2025).

Guo Shan, H., Manchao & Jeon Seokwon. Visualization test and numerical simulations of 2D blasting crack propagation[J]. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 17 (08), 4871–4888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2024.10.013 (2025).

Zhang Jicheng, L. et al. Microfluidic diagnostics: evolution of gas critical paths based on dynamic alterations of cleats wettability[J]. Chem. Eng. J. 515, 163662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2025.163662 (2025).

Guo Shan, H., Manchao, Z., Quan, S., Yulong, W. & Chao, L. Tensile fracture characteristics and directional fracturing mechanism of 2D blasting: experimental investigation and theoretical modelling[J]. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 187, 106059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2025.106059 (2025).

Zhang Jicheng, L., Dawei, Y., Dawei, Z., Xiaoyang, L. & Xuelong, F. Gas recovery and flowback in trans-coal-rock fracture: an in-situ wettability microscale visualization insight[J]. Gas Sci. Eng. 142, 205707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgsce.2025.205707 (2025).

Guo, F., Nong, Z., Xiaowei, F., Zhengzheng, X. & Li, Y. Autonomous prediction of rock deformation in fault zones of coal roadways using supervised machine learning[J]. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 147, 105724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2024.105724 (2024).

Liu Hongtao, Z. et al. Asymmetric deformation and stability control of the roof plate of a return mining roadway through a normal fault[J]. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 58 (2), 2165–2183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-024-04284-9 (2025).

Chen Andong, L., Zhiqiang, N., Lichao, X. & Pengzu, J. Deformation identification and treatment measures for a TBM tunnel crossing a fault zone: A case study[J]. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 162, 106681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2025.106681 (2025).

Shan Renliang, L. et al. Research on the mechanism of asymmetric deformation and stability control of near-fault roadway under the influence of mining[J]. Eng. Fail. Anal. 127, 105492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2021.105492 (2021).

Jiang Jinquan, W., Quanlin, Q. & Hua Evolutionary characteristics of mining stress near the hard-thick overburden normal faults[J]. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 31 (06), 881–887 (2014). (In Chinese).

Xiaoming, S., Jian, W., Chengyu, M. & Zhibiao, G. Control mechanism and technology in the deep-buried through-fault mining roadways[J]. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 29 (06), 100106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kscej.2024.100106 (2025).

Ghabraie Behrooz, R., Gang, Z. & Xiangyang, S. Physical modelling of subsidence from sequential extraction of partially overlapping Longwall panels and study of substrata movement characteristics[J]. Int. J. Coal Geol. 140, 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2015.01.004 (2015).

Jiang Zhenhua, J. et al. Shuai. Research on cooperative control method of comprehensive pressure relief and anchor grouting reinforcement in deep mining roadways[J]. Geomechanics and geophysics for Geo-Energy and Geo-Resources, 10(01): 79. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-024-00765-x

Li Zhenlei, D. et al. Investigation and analysis of the rock burst mechanism induced within fault–pillars[J]. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 70, 192–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2014.03.014 (2014).

Ma Zhenqian, L. et al. Real-time detection and information-based construction of roadways passing through faults: a case study[J]. Environ. Earth Sci. 80, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-021-09610-w (2021).

Wang Hongwei, J. et al. Main factors that control roadway damage when a steeply dipping coal seam crosses a fault[J]. Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk. 15 (01), 2344798. https://doi.org/10.1080/19475705.2024.2344798 (2024).

Zhang Shichuan, L., Yangyang, S., Baotang, S., Xizhen, G. & Liqun Effective evaluation of pressure relief drilling for reducing rock bursts and its application in underground coal mines[J]. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 114, 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2018.12.010 (2019).

Cui Feng, Z., Tinghui, L., Xingping, C. & Jiantao Shan Pengfei. Study on the evolution law of overburden breaking angle under repeated mining and the application of roof pressure relief[J]. Energies 12 (23), 4513. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12234513 (2019).

Chen Yuexia, C., Tingxiang, C. & Xuexi, C. Peng. Comparative analysis of gas-solid-liquid coupling behavior in front of the working face before and after water injection during coal mining[J]. Nat. Resour. Res., 30(02): 1561–1575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11053-021-09816-6 (2021).

Kang Hongpu, L., Huawen, G., Fuqiang, M., Xianzhi, F. & Yanjun Understanding mechanisms of destressing mining-induced stresses using hydraulic fracturing[J]. Int. J. Coal Geol. 196, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2018.06.023 (2018).

He Manchao, Z. & Guolong, G. Longwall mining cutting cantilever beam theory and 110 mining method in China—The third mining science innovation[J]. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 7 (05), 483–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2015.07.002 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Xinjiang Autonomous Region (Grant No. 2024B01017-3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W : Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. M: Methodology, Data curation. Z: Investigation. J: Validation. N: Resources. J: Writing - review & editing. C: Supervision. W: Software.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Yao, M., Liao, Z. et al. The disaster law and control measures of high-stress tunnels in fault areas: a case study. Sci Rep 15, 41562 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25448-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25448-9