Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a global healthcare challenge, requiring cost-effective treatments to improve patient outcomes and resource use. This study assesses the cost-effectiveness of six non-insulin agents (NIAs)—pioglitazone, metformin, dapagliflozin, sitagliptin, empagliflozin, and liraglutide for T2DM management in Iran. Using the UKPDS Outcomes Model 2 (UKPDS-OM2), a 40-year simulation from the healthcare system perspective analyzed data from 440 Iranian patients in the Diabetes Care (DiaCare) study, evaluating direct medical costs and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). Costs were locally sourced, while treatment effects and complication disutility values came from international evidence. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were compared to a threshold of one-time GDP per capita, with uncertainty evaluated via 100 bootstrap iterations. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on sex, age (< 55 vs. ≥55 years), and diabetes duration (< 10 vs. ≥10 years), using the same simulation framework and assumptions. Pioglitazone proved least costly at $1,376.20 PPP with 8.47 QALYs, dominating sitagliptin and empagliflozin, and outperforming metformin, dapagliflozin, and liraglutide, which showed higher costs and limited QALY gains. Subgroup analyses showed that pioglitazone was cost-effective in men, younger patients, and those with longer diabetes duration, while metformin was preferred in women, older patients, and those with shorter disease duration. Bootstrap results showed pioglitazone cost-effective in 52% of iterations and metformin in 46%, with ICERs of $10,554.8–$56,857.13 PPP per QALY. Pioglitazone emerged as the cost-effective option, with metformin as a viable alternative in Iran’s resource-constrained setting. Subgroup analyses highlighted the value of individualized treatment strategies, with pioglitazone and metformin demonstrating variable cost-effectiveness across sex, age, and diabetes duration groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder that has emerged as a global public health challenge1,2. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), approximately 537 million adults were living with diabetes in 2021, with T2DM accounting for over 90% of cases, and this number is projected to rise to 643 million by 20302. The disease imposes a substantial burden on health systems, contributing to complications such as cardiovascular disease, kidney failure, and blindness, which significantly impair patients’ quality of life3,4,5.

Economically, T2DM poses a major challenge, with global healthcare expenditures estimated at $966 billion in 2021, a figure expected to increase as prevalence grows2. In low- and middle-income countries, where resources are limited, the economic burden is particularly pronounced, often leading to catastrophic health expenditures for patients6. In Iran, an estimated 5,702,547 adults (14.15% of those aged 20 years and older) had T2DM in 20227. The total economic burden was $2,905.7 million USD in 2022, including $1,879.2 million USD in direct medical costs, accounting for 12% of Iran’s health expenditure7. Optimal management of T2DM is thus critical to mitigate both health and economic impacts, necessitating strategies that balance clinical efficacy with affordability.

Despite advances in T2DM management, selecting the most appropriate pharmacological intervention remains a complex challenge. These interventions encompass both insulin-based and non-insulin agents (NIAs) therapies, with the latter often serving as important treatments to improve glycemic control and reduce complications8. Commonly used treatments, including Metformin, Pioglitazone, sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors (e.g., Dapagliflozin, Empagliflozin), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors (e.g., Sitagliptin), and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (e.g., Liraglutide), vary widely in their clinical outcomes, side effects, and costs8. For instance, while Metformin is often the first-line therapy due to its low cost and established efficacy, newer agents like SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists offer additional benefits, such as cardiovascular risk reduction, but at significantly higher costs8. These variations create uncertainty in determining which intervention provides the best balance of health benefits relative to cost, particularly in resource-constrained settings. Moreover, patient responses to these therapies differ, with factors such as comorbidities, adherence, and genetic predispositions influencing outcomes. In countries like Iran, where healthcare budgets are limited and out-of-pocket expenses are high, the lack of localized cost-effectiveness data further complicates decision-making, often leading to inefficient resource allocation and suboptimal patient outcomes9.

The choice of pharmacological intervention for T2DM has profound implications for both patients and healthcare systems. Ineffective or overly costly treatments can exacerbate disease progression, increase the incidence of complications, and reduce patients’ health related quality of life (HRQoL), as measured by Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs)8. From an economic perspective, the high costs associated with newer therapies can strain healthcare budgets, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where T2DM prevalence is rising rapidly4. Cost-effectiveness analyses are therefore essential to guide policy decisions, ensuring that limited resources are allocated to interventions that maximize health gains10.

While previous studies have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of T2DM treatments, their findings vary due to differences in populations, healthcare systems, and analytical models. For instance, Guillermin et al. (2012) found that exenatide once weekly dominated sitagliptin and pioglitazone in the U.S11. Laursen et al. (2023) reported that SGLT2 inhibitors were often cost-effective across settings12, while Yuan et al. (2024) showed pioglitazone to be a dominant strategy in a Canadian population with prediabetes13. In the context of Iran, where local data on cost-effectiveness are scarce, there is a pressing need for studies that provide evidence tailored to the national healthcare system, supporting policymakers in optimizing T2DM management strategies.

This study aims to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of NIAs for T2DM, comparing Pioglitazone, Metformin, Dapagliflozin, Sitagliptin, Empagliflozin, and Liraglutide. The primary research question is: which of these interventions offers the optimal approach for managing T2DM in the Iranian healthcare context? The findings are expected to inform clinical guidelines and health policy in Iran, enabling more efficient allocation of resources and improving patient outcomes in the management of T2DM.

Methods

Modeling approach

We used the UKPDS Outcomes Model 2 (UKPDS-OM2) to assess the cost-effectiveness of six NIAs: pioglitazone, metformin, dapagliflozin, sitagliptin, empagliflozin, and liraglutide.

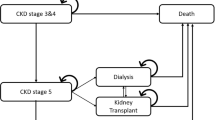

The UKPDS-OM2 is a patient-level simulation tool that predicts the annual probability of diabetes-related events and mortality based on individual risk factors and disease history. This model simulates the long-term outcomes of T2DM, including microvascular complications (such as retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) and macrovascular complications (such as myocardial infarction and stroke) based on data from United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)14. In each yearly cycle, the model calculates the risk of complications and death using parametric proportional hazards equations, comparing these probabilities against random numbers (via Monte Carlo simulation) to determine event occurrence14. Risk factors and event histories are updated annually, and patients continue in the simulation until death or the end of the time horizon14.

The UKPDS-OM2 model internally uses a set of parametric proportional hazard equations, based on the original UKPDS dataset, to estimate annual probabilities of complications and mortality. These equations are driven by updated individual-level characteristics and are not directly defined by user-entered hazard ratios14.

The analysis was conducted over a 40-year time horizon from the healthcare system perspective, considering direct medical costs related to treatment and disease management. A discount rate of 5% was applied annually to both costs and outcomes. Also, we assumed that patients adhered to physician instructions, remaining on their initial treatment throughout the simulation with no switching to other therapies.

A schematic representation of the UKPDS-OM2 model structure used in this study is presented in Fig. 1.

Structure of simulation UKPDS model Source: Reproduced from Hayes et al. (2013)14.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the simulated cohort were derived from a subsample of individuals with T2DM from a large-scale, population-based observational study of diabetes care (DiaCare study) in Iran. This nationwide survey, conducted between 2018 and 2020 across 31 provinces in Iran, included 13,334 participants and provided representative data on patients aged 35–75 years from both urban and rural areas. The detailed sampling methodology of the DiaCare study is provided in the original study protocol15.

In present study a random sample of 500 individuals was initially drawn from the DiaCare database. After excluding incomplete records, 440 samples with complete baseline and clinical parameters were included in the model simulation.

The mean age was 55.13 years, with 44.65% male and a mean diabetes duration of 8.1 years. The mean HbA1c was 8.9%, weight 77.59 kg, and height 1.65 m. The prevalence of smoking was 14.12%, albuminuria 38.27%, and ischemic heart disease (IHD) 9.11%, heart failure 3.64%, myocardial infarction (MI) 7.29%, with other sample characteristics and prior complications available in Table 1.

Treatment effects

The treatment effects of the six NIAs, derived from the latest clinical data, are presented in Table 2, encompassing reductions in HbA1c and changes in body weight relative to placebo.

Costs

In this study, costs related to T2DM treatment and its complications were assessed using data from various sources. These costs were divided into two categories: therapy costs before complications and costs associated with diabetes complications.

The therapy costs prior to the onset of complications include the annual expenses of NIAs, physician visits, and related laboratory tests, estimated separately for each treatment strategy. A bottom-up micro-costing approach was employed, involving the identification of all cost components associated with each regimen and assigning unit costs to each element. The unit prices of the medications were sourced from the official 2023 database of the Iranian Food and Drug Administration. Average daily doses for each NIAs were based on national clinical guidelines and supplemented by expert consultation with endocrinologists. Annual drug costs were calculated by multiplying the unit price by the recommended daily dose and then extrapolating to 365 days. In addition to medication costs, routine care costs including an average of four physician visits per year and biannual laboratory monitoring (HbA1c, fasting glucose, lipid profile, serum creatinine, and urine microalbumin) were included using public healthcare tariffs (Table 3).

Within the model framework, the complications linked to diabetes that were taken into account encompass IHD, MI, heart failure, stroke, amputation, blindness, renal failure, and diabetic ulcers. These complication costs, covering both the event occurrence and annual costs in subsequent years, were included in the model when they occurred. The costs were primarily sourced from various local studies, calculated separately for each complication, and adjusted using healthcare inflation rates based on the study year. All costs from previous years were adjusted to 2023 values using official annual inflation rates specific to the health sector, as reported by the Statistical Center of Iran18.

For MI and heart failure, where local data were unavailable, costs were estimated over one year using standard treatment protocols and consultation with clinical experts. Detailed costs of treatment of complications are presented in Table 4.

To clarify the structure of complication-related costs, we distinguished between the initial cost at the time of event and the annual cost in subsequent years. The former represents the acute and often high-cost medical services required during the first year including hospitalization, surgery, and emergency care. In contrast, the cost in subsequent years reflects the chronic, ongoing management of the complication, such as medications, monitoring, outpatient visits, and rehabilitation. These recurring costs were applied annually throughout the patient’s remaining life unless mortality occurred. Due to the absence of detailed year-by-year cost data in Iran, we adopted a fixed annual cost approach for the subsequent years, consistent with standard practices in cost-effectiveness modeling and prior applications of the UKPDS-OM2 framework.

Health related quality of life

Utility values employed to compute QALY as the final outcome were obtained from credible sources. The baseline utility for individuals with T2DM before complications was established at 0.724. Disutility values linked to diabetes-related complications were also gathered and integrated into the model, reflecting the decrease in health-related quality of life for each specific condition. Due to limited local data, these disutility estimates were primarily drawn from the UKPDS-OM2 study (Table 5).

Base-case cost-utility analysis

The primary outcome measure was the Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER), expressed as the additional cost per QALY gained. To determine cost-effectiveness, the cost-effectiveness threshold (CET) was set at one time the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, which corresponds to $17,659 PPP (purchasing power parity)25. The exchange rate used for currency conversion was 89,391 IRR per international dollar, based on the 2023 Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) conversion factor reported by the World Bank26.

Subgroup analyses

To assess the robustness and policy relevance of the findings across different patient profiles, subgroup analyses were performed based on sex (male vs. female), age (< 55 vs. ≥55 years), and diabetes duration (< 10 vs. ≥10 years).

Subgroup cut-offs were chosen based on established clinical and modeling literature: age 55 years reflects the threshold at which cardiovascular risk and diabetes complications increase markedly; diabetes duration of 10 years is widely recognized as a marker of long-term complication risk; and sex differences are routinely explored given documented variations in metabolic response and cardiovascular outcomes. These thresholds are consistent with prior cost-effectiveness analyses in T2DM populations12,14.

Each subgroup was analyzed separately using the same modeling framework (UKPDS-OM2), parameters, and assumptions as in the base-case analysis. The results, including costs, QALYs, and ICERs, are presented in Supplementary Tables S1 to S3.

One-way sensitivity analysis

To evaluate the robustness of the base-case results and identify key drivers of uncertainty, a one-way sensitivity analysis was performed. This analysis was conducted only for the comparison between metformin and pioglitazone, which represented the most relevant and policy-sensitive contrast identified in the base-case scenario. Key model inputs with the greatest uncertainty were independently varied within plausible low and high ranges for each parameter reported in Supplementary Table S4. These included the annual cost of pioglitazone, annual cost of metformin, annual cost of major diabetes complications (amputation, renal failure, and stroke), discount rates for costs and QALYs, time horizon, and disutility values for renal failure and overall T2DM utility in Iranian patients. The impact of each variable on the Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER) of metformin versus pioglitazone was assessed. Results were presented as a tornado diagram, where the horizontal bars represent the range of ICER variation caused by each parameter. A willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of 17,659 PPP USD per QALY gained (equivalent to one time Iran’s GDP per capita) was used as the benchmark for determining cost-effectiveness.

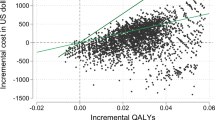

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis (bootstrap)

Bootstrap is a resampling technique widely used to assess uncertainty in statistical models by repeatedly sampling with replacement from the original dataset, thereby estimating the variability of outcomes without requiring strict assumptions about underlying distributions14. In this study, bootstrap analysis was applied through 100 iterations to evaluate the uncertainty surrounding the cost-effectiveness results, specifically targeting costs, QALYs, and the ICER, with the aim of assessing the robustness of the base case analysis.

Also, based on these simulations, a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) was constructed to estimate the probability that each treatment would be considered the most cost-effective option at varying willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds per QALY gained (from $0 to five times the GDP per capita of Iran). The CEAC illustrates the likelihood of each intervention being the optimal choice across a range of WTP values, reflecting decision uncertainty.

All methods were carried out in accordance with internationally recognized guidelines, including the CHEERS 2022 checklist for health economic evaluations27, as well as national ethical regulations for secondary data studies.

All study protocols approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran university of medical sciences (IR.TUMS.EMRI.REC.1401.097).

Results

Base case analysis

In the base case analysis, Pioglitazone had the lowest total expected cost among all evaluated interventions and was selected as the baseline intervention, with an expected cost of $1376.20 PPP and 8.47 expected QALYs. Metformin resulted in a cost of $2036.73 PPP and 8.50 QALYs, Dapagliflozin had a cost of $2190.59 PPP and 8.49 QALYs, Sitagliptin had a cost of $2785.08 PPP and 7.90 QALYs, Empagliflozin had a cost of $3104.81 PPP and 8.19 QALYs, and finally, Liraglutide had a cost of $6054.30 PPP and 8.56 QALYs. Results are presented in Table 6.

Sitagliptin was dominated by Pioglitazone, as they exhibited higher incremental costs ($1599.11 PPP$) alongside reduced QALYs (−0.01). Among the remaining interventions, Metformin, Dapagliflozin, Empagliflozin and Liraglutide incurred higher incremental costs ($660.53 PPP, $814.39 PPP, $1801.86 PPP and $58,978.11 PPP respectively) with modest QALY gains (0.03, 0.02, 0.02 and 0.09 respectively). The ICERs for Metformin, Dapagliflozin and Empagliflozin compared to Pioglitazone were above the cost-effectiveness threshold of $17,659 PPP per QALY, indicating they are not cost-effective, while Liraglutide’s ICER was even higher. Thus, Pioglitazone emerged as the cost-effective option among the six interventions evaluated.

Subgroup analysis results

The subgroup analyses demonstrated variation in cost-effectiveness outcomes across different patient groups. Among male patients and those younger than 55 years, pioglitazone remained the most cost-effective option. In contrast, metformin was cost-effective for female patients and individuals aged 55 years or older. Regarding diabetes duration, metformin was cost-effective in patients with less than 10 years since diagnosis, whereas pioglitazone showed cost-effectiveness in those with disease duration of 10 years or more. These findings underscore the importance of individualized treatment decisions and are summarized in Supplementary Tables S1-S3.

In men and patients < 55 years or ≥ 10 years diabetes duration, pioglitazone had lower costs and comparable or slightly higher QALYs; whereas in women, older adults (≥ 55 years), and those with shorter disease duration (< 10 years), metformin yielded higher QALYs with lower ICERs (Tables S1–S3).

One-way sensitivity analysis

The one-way sensitivity analysis, conducted exclusively for the ICER comparison between metformin and pioglitazone, revealed that variations in several parameters meaningfully influenced the cost-effectiveness outcomes. The discount rate for QALYs, discount rate for costs, annual cost of metformin, annual cost of pioglitazone, and time horizon showed the greatest impact on ICER values, which varied between 7,809 and $44,957 PPP per QALY across tested scenarios. Lower discount rates, reduced drug costs, or extended time horizons decreased the ICER of metformin and, in some cases, pushed it below the cost-effectiveness threshold of $17,659 PPP per QALY, suggesting that metformin could become cost-effective under these favorable conditions. Conversely, higher discount rates, increased pioglitazone costs, or shorter time horizons raised ICER values and consistently maintained pioglitazone as the preferred option. Changes in other variables including the annual costs of complications, utility and disutility parameters had negligible influence. The results, presented in the tornado diagram (Figure S1).

Bootstrap findings

Based on the analysis of 100 bootstrap iterations, pioglitazone was cost-effective in 52% of iterations, while Metformin and dapagliflozin demonstrated cost-effectiveness in 46 and 2% of iterations, respectively with ICERs below the threshold of $17,659 PPP per QALY in those scenarios. Other interventions—sitagliptin, empagliflozin, and liraglutide—showed no likelihood of being cost-effective. Table 7 provides detailed ranges of costs, QALYs, and ICERs for all interventions.

The CEAC illustrates that at very low WTP thresholds, pioglitazone has the highest probability of being cost-effective due to its low expected cost. As the threshold increases to approximately twice the per capita GDP, the probability of cost-effectiveness for metformin rises. Newer oral agents, such as dapagliflozin, begin to show an increased probability of being the most cost-effective option from around one times the GDP per capita threshold. empagliflozin becomes a more likely cost-effective option beyond two times the GDP per capita threshold. In contrast, sitagliptin and liraglutide do not demonstrate meaningful probabilities of cost-effectiveness across the examined WTP range, up to five times the GDP per capita (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Present study assessed the cost-effectiveness of six NIAs (pioglitazone, metformin, dapagliflozin, sitagliptin, empagliflozin, and liraglutide) for managing T2DM in Iran. In the base-case analysis, pioglitazone emerged as the cost-effective option among the six interventions compared, with metformin identified as a nearly optimal alternative. One-way sensitivity analysis showed that the comparative cost-effectiveness between metformin and pioglitazone is moderately robust, but influenced by several key assumptions. While pioglitazone remained cost-effective in some scenarios, lower discount rates, longer time horizons, or reduced annual drug costs could decrease the ICER of metformin below the willingness-to-pay threshold, potentially changing the preferred option.

The bootstrap findings and CEAC results reinforce the conclusion that cost-effectiveness is sensitive to the assumed societal WTP. While pioglitazone and metformin demonstrate relatively stable cost-effectiveness under lower WTP thresholds, newer agents such as SGLT2 inhibitors only emerge as viable options at significantly higher thresholds often exceeding two times the GDP per capita. This pattern reflects a fundamental affordability-efficiency trade-off in low- and middle-income settings: although newer drugs may offer incremental health gains, their higher costs limit their acceptability within constrained budgets. The near-zero probability of cost-effectiveness for sitagliptin and liraglutide across a wide WTP range further highlights the need for strategic price negotiations and value-based reimbursement models. These findings underscore the importance of embedding uncertainty analysis within HTA frameworks to inform evidence-based prioritization and sustainable policy decisions.

The subgroup analyses further refined our understanding of cost-effectiveness by highlighting differential outcomes across patient demographics. Specifically, pioglitazone remained cost-effective in male patients and younger individuals (< 55 years), while metformin emerged as the preferred option in female patients and those aged ≥ 55 years. Similarly, patients with a shorter duration of diabetes (< 10 years) benefited more from metformin, whereas pioglitazone was more favorable in individuals with longer disease history. These differences may reflect variations in treatment response, metabolic profiles, and complication risk across groups, suggesting that tailored pharmacological strategies based on patient characteristics may enhance both clinical and economic outcomes in T2DM management.

The results of this study show both similarities and differences with previous research on the cost-effectiveness of NIAs, which can be explained by variations in healthcare systems, study methodologies, drug pricing policies, and access to medications across different settings. Guillermin et al. (2012) conducted a long-term cost-consequence analysis in the United States, comparing exenatide once weekly (ExQW) with sitagliptin and pioglitazone using the IMS CORE Diabetes Model. Their study found ExQW dominated both comparators, yielding 0.28 and 0.24 additional QALYs and cost savings of $2,215 and $933 per patient, respectively, due to reduced cardiovascular and neuropathic complications11. In contrast, our study identified pioglitazone as the cost-effective strategy in the base-case analysis, likely due to its lower acquisition cost in Iran, where over 80% of NIAs are domestically produced, making it more affordable than imported drugs like ExQW28.

Laursen et al. (2023) conducted a systematic review of cost-effectiveness studies on newer NIAs, noting that within-class comparisons often favored injectable and oral semaglutide (GLP-1 receptor agonists) and empagliflozin (SGLT2 inhibitors). However, cross-class comparisons showed mixed results, with SGLT2 inhibitors dominating GLP-1 receptor agonists in six studies and GLP-1 receptor agonists being cost-effective in nine studies12. Our findings differ, as pioglitazone, an older drug, outperformed newer agents like empagliflozin and liraglutide, possibly due to cost advantages in Iran’s resource-limited setting.

Yuan et al. (2024) assessed low-dose pioglitazone (15 mg daily) versus placebo in a Canadian prediabetes population with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) using a 5-state Markov model, finding pioglitazone dominated with $30,287 savings and 6.37 additional QALYs over 36 years13. This supports our base-case finding of pioglitazone’s cost-effectiveness, though in a different population and context. Valentine et al. (2009) assessed pioglitazone versus placebo in high-risk T2DM patients in the US. Pioglitazone increased life expectancy by 0.237 years and QALYs by 0.166, with a lifetime cost increase of $7,305, resulting in an ICER of $44,105 per QALY gained29. This aligns with our base-case finding of pioglitazone’s cost-effectiveness, though the ICER reflects a higher CET in the US compared to Iran’s context.

Despite these cost-effectiveness findings, the selection of NIAs for T2DM patients should not be solely based on economic evaluations. Several factors, including individual patient characteristics, variability in treatment response, lifestyle considerations, potential side effects, and clinical preferences, also play a critical role in therapeutic decision-making. T2DM is a chronic and multifaceted condition, and patients may respond differently to various NIAs, meaning that an option deemed less economically optimal might still be the most clinically appropriate choice for certain individuals. Also, the results of present study indicated that the average cost-effectiveness ratio (ACER) for all evaluated NIAs fell below the cost-effectiveness threshold in Iran, suggesting that these interventions can be considered cost-effective without comparison to each other.

A key strength of this study is the use of the UKPDS-OM2, one of the most reliable and widely used models for evaluating the long-term outcomes of T2DM, which is freely available to researchers14. The choice of this model was due to its appropriate structural alignment with the dataset from the DiaCare study and its ability to simulate both microvascular and macrovascular diabetes-related outcomes, enhancing the robustness of our projections14. Another major strength is the utilization of a sample from the comprehensive DiaCare study in Iran, providing a representative cohort for analysis. Additionally, the simultaneous comparison of six non-insulin interventions commonly used within Iran’s healthcare system offers valuable. The bootstrap analysis further strengthens the study by addressing parameter uncertainty, providing a more comprehensive assessment of variability in outcomes14.

In evaluating diabetes treatments, various economic models have been used, each with unique structural features that can influence results. The UKPDS-OM2 is a patient-level simulation model, which allows for annual updates of individual risk factors and tracks history-dependent complications. This structure enables more granular risk estimation and reflects heterogeneity in patient outcomes over time. In contrast, Markov cohort models—commonly used in earlier studies—assume fixed transition probabilities and homogeneous populations within health states, which can oversimplify the chronic and progressive nature of T2DM.

These structural differences can significantly affect outcomes. For instance, patient-level models like UKPDS-OM2 may yield more conservative or individualized QALY gains, especially when long-term microvascular and macrovascular risks are strongly influenced by baseline heterogeneity. Therefore, the selection of model influences not only ICERs but also the robustness and interpretability of the findings for local policy-making.

However, this study has certain limitations that must be considered. One limitation is the lack of reliable domestic evidence on the disutility associated with diabetes complications, which could have affected the accuracy of QALY estimates in the context. Another limitation is the absence of cost data for certain complications, such as MI and heart failure, which led to the estimation of costs in some cases based on treatment protocols and consultation with clinical specialists, potentially introducing uncertainty into the cost-effectiveness results.

Although the UKPDS-OM2 model is widely validated and used in various settings, it was originally developed using data from a UK-based cohort of primarily white, middle-aged individuals. Therefore, its direct applicability to non-UK populations such as Iran may be limited. In this study, while the model structure was not recalibrated, we utilized a nationally representative Iranian cohort from the DiaCare study as input data to improve contextual relevance. While full recalibration was not feasible, we undertook several steps such as using national utility values, local expert validation, and plausibility checks to enhance its applicability. Nevertheless, the lack of a fully localized model remains a limitation of this study.

In Iran, the national diabetes control program focuses primarily on screening, diagnosis, and lifestyle modification. Pharmacological treatment is guided by national guidelines, yet the insurance coverage for newer anti-diabetic agents remains limited. The findings have significant implications for clinical practice and health policy in Iran, where T2DM affects 14.15% of adults aged 20 years and older and accounts for 12% of total health expenditure in 20227. Our findings suggest that pioglitazone offers a highly cost-effective alternative, especially for male, younger, and long-duration patients. Pioglitazone’s position as the cost-effective option in the base-case analysis suggests it could be prioritized in guidelines and insurance coverage. Also, the bootstrap results support metformin as a cost-effective alternative, given its affordability.

These insights can be used by policy-makers to prioritize cost-effective medications in the basic health insurance benefit package; design value-based pricing or reimbursement schemes; reduce financial barriers to effective treatment by targeted subsidies; allocate budget more efficiently to maximize population-level QALY gains; reassess current reimbursement status of newer drugs based on cost-effectiveness, not only clinical efficacy.

Conclusion

Findings suggest pioglitazone emerged as the cost-effective strategy among the evaluated NIAs for T2DM management in Iran, closely followed by metformin as a viable alternative. Sensitivity analysis further indicated metformin’s potential as a cost-effective option in numerous scenarios. These results underscore pioglitazone and metformin as economically viable choices in Iran’s resource-constrained setting. Policymakers should prioritize these affordable therapies to enhance T2DM management and optimize resource allocation.

Subgroup analyses highlighted the value of individualized treatment strategies, with pioglitazone and metformin demonstrating variable cost-effectiveness across sex, age, and diabetes duration groups. These findings support the integration of personalized approaches in national treatment guidelines and reimbursement policies.

Exploring the cost-effectiveness of combination therapies, particularly those involving affordable drugs like pioglitazone and metformin, could offer insights into optimizing treatment strategies. Moreover, incorporating real-world data from Iranian patients, including subgroup analyses based on factors such as age, comorbidities, or disease severity, would enhance the applicability of findings to diverse clinical scenarios.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to licensing and ownership restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Goyal, S. & Vanita, V. The rise of type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents: an emerging pandemic. Diab./Metab. Res. Rev. 41 (1), e70029 (2025).

Magliano, D. J., Boyko, E. J. IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th edition scientific committee (International Diabetes Federation, Brussels, 2021).

World Health, O. Global Report on Diabetes (World Health Organization, 2016).

Al-Worafi, Y. M. Epidemiology and Burden of Diabetes Mellitus in Developing Countries, in Handbook of Medical and Health Sciences in Developing Countries: Education, Practice, and Research, Y.M. Al-Worafi, Editor. Springer International Publishing: Cham. pp. 1–27. (2023).

Zakir, M. et al. Cardiovascular complications of diabetes: from microvascular to macrovascular pathways. Cureus 15 (9), e45835 (2023).

Rahman, T., Gasbarro, D. & Alam, K. Financial risk protection from out-of-pocket health spending in low-and middle-income countries: a scoping review of the literature. Health Res. Policy Syst. 20 (1), 83 (2022).

Mohammadi, A. et al. Economic burden of type 2 diabetes in Iran in 2022. BMC Public. Health. 25 (1), 35 (2025).

ElSayed, N. A. et al. Introduction and methodology: standards of care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care. 46 (Supplement_1), S1–S4 (2022).

Jahanmehr, N. et al. The projection of iran’s healthcare expenditures by 2030: evidence of a Time-Series analysis. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 11 (11), 2563–2573 (2022).

European Observatory Health Policy Series, in Health system efficiency: How to make measurement matter for policy and management, J. Cylus, I. Papanicolas, and P.C. Smith, Editors. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies © World Health Organization 2016 (acting as the host organization for, and secretariat of, the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies). Copenhagen (Denmark). (2016).

Guillermin, A. L. et al. Long-term cost-consequence analysis of exenatide once weekly vs sitagliptin or Pioglitazone for the treatment of type 2 diabetes patients in the united States. J. Med. Econ. 15 (4), 654–663 (2012).

Laursen, H. V. B. et al. A systematic review of Cost-Effectiveness studies of newer Non-Insulin antidiabetic drugs: trends in Decision-Analytical models for modelling of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacoeconomics 41 (11), 1469–1514 (2023).

Yuan, F., Spence, J. D. & Tarride, J. E. Cost-Utility analysis of Low-Dose Pioglitazone in a population with prediabetes and a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 13 (21), e034531 (2024).

Hayes, A. J. et al. UKPDS outcomes model 2: a new version of a model to simulate lifetime health outcomes of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus using data from the 30 year united Kingdom prospective diabetes study: UKPDS 82. Diabetologia 56 (9), 1925–1933 (2013).

Shafiee, G. et al. Management goal achievements of diabetes care in iran: study profile and main findings of diacare survey. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 22 (1), 355–366 (2023).

Tsapas, A. et al. Comparative efficacy of glucose-lowering medications on body weight and blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 23 (9), 2116–2124 (2021).

Tsapas, A. et al. Comparative effectiveness of Glucose-Lowering drugs for type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and network Meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 173 (4), 278–286 (2020).

Iran, S. C. Consumer Price Index – Health Sector. (2023).

Shirvani Shiri, M. et al. Hospitalization expenses and influencing factors for inpatients with ischemic heart disease in iran: A retrospective study. Health Scope. 11 (1), e117711 (2022).

Kazemi, Z. et al. Estimation and predictors of direct hospitalisation expenses and in-hospital mortality for patients who had a stroke in a low-middle income country: evidence from a nationwide cross-sectional study in Iranian hospitals. BMJ Open. 12 (12), e067573 (2022).

Movahed, M. S. et al. Economic burden of stroke in iran: A Population-Based study. Value Health Reg. Issues. 24, 77–81 (2021).

Shahtaheri, R. S. et al. Long-term cost-effectiveness of quality of diabetes care; experiences from private and public diabetes centers in Iran. Health Econ. Rev. 12 (1), 44 (2022).

Jha, V. et al. Global economic burden associated with chronic kidney disease: A pragmatic review of medical costs for the inside CKD research programme. Adv. Ther. 40 (10), 4405–4420 (2023).

Javanbakht, M. et al. Health related quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in iran: a National survey. PLoS One. 7 (8), e44526 (2012).

Bank, W. GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) - Iran, Islamic Rep.

Bank, W. PPP conversion factor, GDP (LCU per international $) - Iran, Islamic Rep.; Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.PPP?locations=IR

Husereau, D. et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) Statement: Updated Reporting Guidance for Health Economic Evaluations Vol. 7, p. 23814683211061097 (MDM Policy & Practice, 2022). 1.

Zarei, L. et al. Affordability of medication therapy in diabetic patients: A Scenario-Based assessment in iran’s health system context. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 11 (4), 443–452 (2022).

Valentine, W. J. et al. Long-term cost-effectiveness of Pioglitazone versus placebo in addition to existing diabetes treatment: a US analysis based on proactive. Value Health. 12 (1), 1–9 (2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD: Conceptualization, data collection, modeling, interpretation of results, writing - review and editing of the manuscript, final approval of the version to be published.RD: Conceptualization, critical review of the methodology and model structure, interpretation of results, final approval of the version to be published.SD: Interpretation of results, writing - review and editing of the manuscript,, final approval of the version to be published.RH: Conceptualization, data collection, critical review of the methodology, review and editing of the manuscript, final approval of the version to be published.GSH: Supervision, Validation of clinical content, review and editing of the manuscript, final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All study protocols approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran university of medical sciences (IR.TUMS.EMRI.REC.1401.097).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Darvishi, A., Daroudi, R., Dehghan, S. et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of six non insulin agents for type 2 diabetes in Iran using a patient level simulation with UKPDS OM2. Sci Rep 15, 41536 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25456-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25456-9