Abstract

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICCA) is a highly aggressive bile duct cancer with limited treatment options and poor prognosis. This study aims to develop a gene signature-based model to predict ICCA patient survival. We identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from an ICCA mRNA microarray dataset and applied survival, Cox, and LASSO regression analyses to select key genes for constructing the GPSICCA risk score model. The model was then validated in two additional ICCA cohorts, and its relationship with the tumor microenvironment (TME) was analyzed. Additionally, multiplex fluorescent immunohistochemistry (mfIHC) was conducted to examine the expression of key genes in ICCA samples. The expression of COL4A1, GULP1, ITGA6, and STC1 was used to construct the gene set-based prognostic signature for ICCA (GPSICCA) risk score model, and mfIHC confirmed their expression in ICCA samples. The model effectively stratified patients into high- and low-risk groups, with high-risk patients showing significantly worse survival. The GPSICCA score was positively correlated with stromal and immune scores, suggesting its predictive capability is related to TME involvement in ICCA. The GPSICCA model is a strong predictor of survival in ICCA patients and could help guide treatment strategies and identify potential therapeutic targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a rare and aggressive cancer that arises in the bile ducts, either inside the liver (intrahepatic CCA, or ICCA) or outside of it (extrahepatic CCA, or ECCA). Several risk factors contribute to its development, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis, chronic liver conditions, bile duct cysts, liver fluke infections, and hepatitis B or C infections1,2.

One of the major challenges in treating CCA is that it is frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage, limiting treatment options and contributing to poor outcomes3. Despite advances in cancer therapies, progress in treating CCA has been slow, and the prognosis remains grim. The 5-year survival rate for unresectable ICCA is less than 5–10%, and even for those undergoing liver resection, only 20–35% survive beyond five years4. Given these dismal statistics, there is a pressing need for new therapies to combat this lethal disease.

Predicting clinical outcomes can significantly guide treatment strategies, and the use of biomarkers and prognostic models, particularly those leveraging machine learning, has gained attention in various cancers5. Machine learning, a subset of artificial intelligence, uses statistical methods, probabilistic models, and optimization strategies to enable computers to learn from historical data and uncover subtle patterns within large and/or complex datasets. This ability makes it especially valuable in the medical field, where analyzing intricate genomic and proteomic data is often critical. Consequently, machine learning plays a significant role in cancer diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis6,7.

In the context of ICCA, multiple prognostic models have been proposed to predict the survival of ICCA patients8,9,10. However, traditional approaches, such as the Cox proportional hazards model and the Kaplan-Meier (KM) estimator, often fall short in capturing the complex and nonlinear characteristics of medical data11. Additionally, most published conventional prognostic models have shown limited performance when subjected to external validation12. In contrast, machine learning methods, such as Random Survival Forests and Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO), offer increased flexibility, allowing for the modeling of intricate interactions and hidden patterns with greater accuracy11,13,14. Still, prognostic models for ICCA that incorporate gene expression data and machine learning remain limited.

The tumor microenvironment (TME)—the surrounding non-cancerous cells, extracellular matrix, signaling molecules, and blood vessels—plays a critical role in tumor behavior15,16, and there is compelling evidence linking TME to ICCA progression17,18,19. The TME has demonstrated substantial prognostic significance, with immune infiltration, stromal activation, and immunosuppressive mechanisms emerging as critical factors in predicting patient outcomes20,21. Despite this, there remains a lack of prognostic models specifically focused on TME-related gene expression for ICCA.

In this study, we identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) by comparing tumor tissues with adjacent non-tumor (NT) tissues in an ICCA dataset. Using KM survival and Cox regression analyses, we developed a prognostic model based on the expression of four DEGs. We then confirmed the expression of these DEGs by multiplex fluorescent immunohistochemistry (mfIHC). Finally, we validated this model with two additional ICCA datasets and further explored its connection to TME characteristics.

Materials and methods

Transcriptomic analysis dataset collection and pre-processing

All transcriptomic datasets were sourced from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The microarray dataset E-MTAB-638922, which includes 78 ICCA and 31 NT samples, was processed using the Robust Multi-array Average (RMA) algorithm in the R package “oligo” (v1.64.1) for background adjustment and quantile normalization. Probe annotation was conducted using the GPL17585 platform file from GEO, and the resulting expression data were standardized via z-score normalization. For the CCA microarray dataset GSE897492, containing 118 tumor samples, we applied the “lumi” R package to adjust for background noise, followed by log2(count + 1) transformation and z-score normalization.

The RNA-seq dataset GSE10794323, which includes 30 ICCA and 27 NT samples, was pre-processed by converting Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads (RPKM) to Transcripts Per Million (TPM), followed by z-score normalization. Patients with an overall survival of less than 30 days in all these cohorts were excluded. A summary of the final samples used is presented in Table S1.

DEG analysis

To identify DEGs between ICCA and NT samples in the E-MTAB-6389 dataset, we utilized the R package “limma” (v3.56.2), applying a |log2 fold change| > 1 and a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05.

Multivariate cox analysis

We conducted multivariate Cox regression analysis using the R package “finalfit” (v1.0.8), including both forward and backward selection, and visualized the results with the “forestplot” R package (v3.1.3).

Prognostic model construction

DEGs identified from the E-MTAB-6389 dataset underwent KM survival analysis and univariate Cox regression using the ‘survidiff’ function within the R package “survival” (v3.7-0). Genes with a P-value < 0.1 in both analyses were further evaluated using LASSO Cox regression with the “Glmnet” R package (v4.1–8). The identified genes are detailed in Table S2. Subsequently, we employed stepwise Cox regression to optimize the model by incorporating the expression of each gene24,25. Genes that significantly enhanced model accuracy were selected to build the final gene set-based prognostic signature for the ICCA (GPSICCA) model. This model was constructed by multiplying the expression level of each marker gene by the respective regression coefficients obtained from stepwise Cox regression.

To validate the model’s predictive capability, we tested it on the GSE89749 and GSE107943 cohorts. The optimal cutoff for high-risk and low-risk ICCA patients was determined using the “surv_cutpoint” function from the R package “survminer” (v0.4.9). KM survival curves were visualized using the “survival” and “survminer” R packages, while heatmaps and bar plots were generated using the “pheatmap” (v1.0.12) and “graphics” (v4.3.0) R packages. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed using the “timeROC” (v0.4) R package.

TME feature analysis

To analyze TME features, we assessed 75, 111, and 30 tumor samples from the E-MTAB-6389, GSE89749, and GSE107943 datasets, respectively, for stromal and immune scores using the R packages “ESTIMATE” (v1.0.13) and “GSVA” (v1.50.0) (Table S3). The Pearson correlation between the risk score and stromal or immune scores was visualized using the R package “ggpubr” (v0.6.0). Survival analysis based on stromal and immune scores was carried out using “survival” and “survminer”.

For cell type delineation in the TME, we used the R package “xCell” (v1.1.0), with the results outlined in Table S4. Panimmune gene set and immunomodulatory gene analyses were performed using “GSVA,” and the results are presented in Table S5 and Table S6, respectively. For both “xCell” and “GSVA” analyses, the following thresholds were applied: overall survival (log-rank test, P < 0.05) and GPSICCA risk score (Pearson correlation test, |r| ≥ 0.40, P < 0.05). The findings were visualized using “forestplot”.

MfIHC

Samples from five patients (2 male and 3 female, aged 49 to 71) who were diagnosed with ICCA and underwent curative intent resection at our hospital between 2019 and 2023 were used for mfIHC analysis. ICCA paraffin Sect. (5 μm thick) were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated with gradient ethanol solutions. The samples were then rinsed with ddH2O and treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide to block endogenous peroxidase activity and underwent antigen retrieval. Blocking was performed using 5% goat serum, after which the sections were incubated with a primary antibody at 37 °C for 2 h and then washed with PBST (PBS + 0.1% Tween 20), followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody solution for 30 min. Next, the sections were washed with PBST again and treated with one fluorophore (RS0039, Immunoway) for 5 min, followed by washing with PBST. Subsequently, the sections were subjected to antigen retrieval again and followed all the IHC steps using another primary antibody. These steps were repeated for every primary antibody. Finally, the sections were washed with PBST and mounted with a 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, stains nuclei)-containing mounting medium (P0131, Beyotime). The results were imaged by a Zeiss LSM 900 confocal microscope. Information on antibodies is presented in Table 1.

Results

Establishment of the GPSICCA prognostic model

To create a prognostic model for ICCA, we first analyzed the E-MTAB-6389 dataset to identify DEGs between ICCA tumorous and NT samples. These genes were then assessed using survival and univariate Cox regression analyses, and the resulting 86 genes were further subjected to LASSO regression analysis. 12 out of these genes were selected for subsequent stepwise Cox regression multivariate analysis (Fig. 1A and B, Table S2). From this analysis, 7 genes were identified, among which 4 key genes with hazard ratios (HR) greater than 1 were chosen to construct the optimized GPSICCA model (Fig. 1C, Table S2). The risk score was calculated using the following formula: (1.1771 * expression of COL4A1) + (0.6895 * expression of GULP1) + (0.7011 * expression of ITGA6) + (0.6168 * expression of STC1). We subsequently validated the presence of these genes in ICCA samples using mfIHC. This analysis revealed strong expression of the genes in ICCA samples (Fig. 2). Consistently, CXCL17, which promotes the progression of liver cancer and regulates immune infiltration26,27, was also highly expressed in ICCA samples (Fig. 2).

Performance evaluation of the GPSICCA model

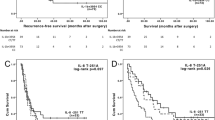

To validate the GPSICCA model’s predictive accuracy regarding clinical outcomes in ICCA patients, survival analyses based on risk scores were conducted. The results showed that patients with a high-risk score (N = 55) in the E-MTAB-6389 cohort had significantly worse overall survival compared to those with a low-risk score (N = 116) (HR = 3.594; P < 0.0001; Fig. 3A). Similarly, in the GSE89749 dataset, patients in the high-risk group (N = 229) had a poorer prognosis than those in the low-risk group (N = 64) (HR = 5.59; P = 0.001; Fig. 3B). In the GSE107943 cohort, patients were also divided into high-risk (N = 21) and low-risk (N = 66) groups, with high-risk patients demonstrating worse survival outcomes (HR = 4.669; P = 0.003; Fig. 3C). The relationship between the expression levels of the 4 prognostic genes, GPSICCA risk score, and clinical outcomes in these cohorts is depicted in Figs. 3D-F. We further evaluated the prognostic performance of the GPSICCA model using ROC analysis. The results demonstrated that the model performed satisfactorily in the E-MTAB-6389 and GSE89749 datasets, particularly in predicting 3-year and 5-year survival. However, its performance in the GSE107943 dataset was less robust, due to the limited number of patients (Fig. 3G-I). These findings suggest that the GPSICCA model effectively predicts survival in ICCA patients.

Evaluation of the GPSICCA model’s predictive power for ICCA patient survival. (A-C) KM survival curves comparing overall survival in ICCA patients with high and low GPSICCA risk scores in three cohorts: E-MTAB-6389 (A), GSE89749 (B), and GSE107943 (C). (D-F) Heatmaps and bar charts showing the relationship between the expression levels of the four prognostic genes and GPSICCA risk scores, along with survival status in the E-MTAB-6389 (D), GSE89749 (E), and GSE107943 cohorts (F). (G-I) ROC curves indicating the prognostic performance of the GPSICCA model in the E-MTAB-6389 (G), GSE89749 (H), and GSE107943 cohorts (I).

GPSICCA risk score correlates with immune or stromal score

Since COL4A1, ITGA6, and STC1 have been linked to TME in other contexts28,29,30, and TME is closely associated with CCA progression, we explored the connection between the GPSICCA risk score and immune/stromal scores, aiming to delineate the mechanism by which our model predicts the survival of ICCA patients. Using the ESTIMATE package, we categorized TME into immune and stromal subcomponents, calculating their respective scores using GSVA. Pearson correlation analysis of 216 patients across 3 cohorts revealed a moderate positive correlation between GPSICCA risk score and immune score (cor = 0.22, P = 0.0012, Fig. 4A) and a strong positive correlation with stromal score (cor = 0.58, P < 2.2e-16, Fig. 4B). Furthermore, both immune and stromal scores were significantly associated with overall survival in ICCA patients (HR = 2.071; P = 0.004 for immune score, Fig. 4C; HR = 1.943; P = 0.004 for stromal score, Fig. 4D). These results suggest that a high GPSICCA score is indicative of a tumor-promoting TME in ICCA.

Association between GPSICCA risk scores, immune and stromal scores, and ICCA patient survival. (A, B) Scatter plots illustrating significant positive correlations between GPSICCA risk scores and immune scores (A) as well as stromal scores (B) in ICCA patients. (C, D) KM survival curves showing the overall survival of ICCA patients with high and low immune scores (C) and stromal scores (D).

Association of GPSICCA risk score with TME cell types, panimmune gene sets, and Immunomodulatory (IM) genes in ICCA samples

To further understand the relationship between the GPSICCA score and specific TME cell types, we utilized the “xCell” algorithm. The analysis identified 8 cell types significantly associated with the GPSICCA score. Among these, Th2 cells, mesangial cells, astrocytes, smooth muscle cells, and melanocytes exhibited a positive correlation, while natural killer T (NKT) cells, class-switched memory B cells, and osteoblasts were negatively associated with GPSICCA scores (Fig. 5A).

Next, we examined panimmune gene sets31 and IM genes32 potentially linked to the GPSICCA score. Our findings revealed that 17 gene sets were significantly correlated with the GPSICCA score. Of the 15 positively correlated gene sets, 4 were related to interferon (IFN) responses, while natural killer (NK) and Th17 cell-related gene sets were negatively correlated with the GPSICCA score (Fig. 5B). Notably, gene sets related to NK cells showed differential correlations, as CD56dim NK cells had a positive association. Additionally, the expression levels of IL10, ENTPD1, ITGB2, and TNFRSF14 were positively correlated with the GPSICCA score, while TGFB1, PDCD1, and EDNRB exhibited negative correlations (Fig. 5C). Collectively, these results provide insights into the underlying mechanisms and potential targets associated with the GPSICCA score.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a prognostic model for predicting the survival of ICCA patients by using a publicly available ICCA dataset. The model was constructed using the expression profiles of four DEGs. Its predictive capability was further validated in two additional ICCA cohorts, demonstrating its robustness in different datasets.

The GPSICCA prognostic model, developed using machine learning, may mark a significant improvement in predicting outcomes for ICCA patients by integrating novel gene expression signatures and TME characteristics, features often overlooked by conventional models. Incorporating four key genes (COL4A1, GULP1, ITGA6, and STC1) that are identified through rigorous statistical analysis, the model captures crucial molecular determinants of prognosis. The GPSICCA risk score also correlates strongly with immune and stromal components of the TME, as well as specific immune cell types and immunomodulatory genes, reinforcing its biological relevance. This comprehensive integration enhances predictive accuracy and enables consistent stratification of patient survival across multiple independent cohorts.

Unlike traditional prognostic systems for various cancers that typically stratify patients into three distinct categories—poor, intermediate, and favorable prognosis33,34—the GPSICCA model introduces a two-tier risk classification. Based on the expression of four key genes, the GPSICCA score clearly divides patients into high- and low-risk groups, as consistently demonstrated across multiple independent cohorts. This binary stratification enhances clinical utility by simplifying risk assessment and reducing ambiguity in patient categorization, which may ultimately facilitate more decisive therapeutic planning.

Among the four genes included in the GPSICCA risk score, three—COL4A1, ITGA6, and STC1—are consistently implicated in cancer. COL4A1 encodes a collagen protein and acts as an oncogene in hepatocellular carcinoma by activating the FAK-Src signaling35. COL4A1 also appears to be oncogenic as its overexpression promotes the proliferation of breast and oral squamous cancer cells36,37. Similarly, ITGA6, which encodes α6-Integrin, is a crucial cell adhesion molecule that regulates the malignant behaviors of various cancers, such as breast cancer38, pancreatic cancer39, and ovarian cancer40. ITGA6 promotes proliferation, metastasis, and drug resistance in these cancers41. STC1 also facilitates metastasis and chemoresistance of ovarian cancer cells by controlling the FOXC2/ITGB6 signaling42, promotes metastasis of breast cancer by stimulating the EGFR-ERK-S100A4 signaling43, and predicts poor survival in colorectal cancer patients44. In line with these roles, our analysis found that these genes are overexpressed in ICCA and are linked to unfavorable clinical outcomes, suggesting their oncogenic potential in ICCA, though their precise function in ICCA cells remains to be explored.

In contrast, GULP1 appears to have a context-dependent role in cancer. In urothelial carcinoma, it functions as a tumor suppressor through the NRF2-KEAP1 signaling pathway45. GULP1 also acts as a tumor suppressor in ovarian cancer, with reduced expression due to promoter methylation46. In ICCA, however, GULP1 is upregulated and correlated with poor survival, suggesting it may have an oncogenic function in this context. Its impact on ICCA requires further functional validation.

Notably, the expression of these four genes overlaps with TME regulator CXCL1747, indicating their involvement in the TME of ICCA, particularly COL4A1, ITGA6, and STC1, which are known to influence TME in other cancers29,48,49. The role of GULP1 in TME remains unclear. Our analysis revealed that the GPSICCA risk score is positively correlated with immune and stromal scores, both of which predict poor survival outcomes in ICCA patients. This implies that these genes may influence immune cell infiltration and stromal remodeling in ICCA tissues.

Among the TME cell types correlated with the GPSICCA risk score, Th2 cells had the most significant positive association. Th2 cells’ role in TME varies across cancers; in colon and pancreatic cancers, they have anti-tumor effects, while in breast cancer, inhibiting Th2-mediated immunity improves response to immunotherapy50,51. In ICCA, the positive association of Th2 cells with the GPSICCA score suggests they may be oncogenic, though further investigation is needed. Conversely, the negative association with NKT cells, which typically have anti-cancer functions52, suggests that these cells may be suppressed by the signature genes in the ICCA microenvironment.

Correlation analysis with panimmune gene sets revealed a significant link between the GPSICCA score and IFN responses. Although IFNs generally have anti-tumor effects, in some cases, they may promote immune evasion by cancer cells53, raising the possibility that IFNs could be oncogenic in ICCA. This requires further study. Only two panimmune gene sets, regulating NK cells and Th17 cells, were negatively correlated with the GPSICCA score. NK cells are known to inhibit CCA54,55, while Th17 cells can have both pro- and anti-tumor roles56, though their function in ICCA remains to be elucidated.

Regarding specific immunomodulatory genes, ENTPD1 showed the strongest positive correlation with the GPSICCA score, indicating a potential oncogenic role in ICCA. Consistent with this, ENTPD1, expressed by regulatory T cells (Tregs), enhances the growth of hepatic metastatic tumors by promoting tumor cell proliferation via scavenging extracellular ATP57,58. EDNRB, which showed the strongest negative correlation with the GPSICCA score, is considered a tumor suppressor in other cancers, with higher expression linked to better survival in triple-negative breast cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma59,60. Although the specific roles of these genes in ICCA remain unclear, they could serve as promising therapeutic targets for ICCA patients.

While our prognostic model for ICCA demonstrates significant value in predicting patient outcomes, further validation in larger patient cohorts is necessary to confirm its broader clinical applicability. In particular, it remains to be determined whether the model is universally applicable across all ICCA patients or whether its prognostic value is limited to specific subgroups, such as those undergoing treatments with curative intent, like surgical resection. Additionally, deeper exploration into the roles of the four signature genes will provide critical insights into the underlying mechanisms that drive ICCA progression and the model’s predictive power. To improve the biological relevance and interpretability of the model, it is also crucial to link the aberrant expression of these genes to specific TME cell populations using single-cell profiling techniques. Understanding these cancer-related genes will help establish a stronger foundation for utilizing this model in clinical settings and may reveal therapeutic opportunities for targeting these genes in ICCA treatment.

In summary, this study introduces a novel prognostic model that could enhance ICCA patient stratification and treatment strategies. Moreover, our findings shed light on the molecular basis of ICCA, emphasizing the therapeutic potential of the identified signature genes for future clinical interventions.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are available on the GEO website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi? acc=GSE89749) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi? acc=GSE107943) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi? acc=GPL17585). All other data are included in the manuscript and supplementary files and are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Kongpetch, S. et al. Pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma: from genetics to signalling pathways. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 29 (2), 233–244 (2015). PubMed PMID: 25966424.

Jusakul, A. et al. Whole-Genome and epigenomic landscapes of etiologically distinct subtypes of cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 7 (10), 1116–1135. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-17-0368 (2017). Epub 20170630.

Patel, T. Cholangiocarcinoma–controversies and challenges. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8 (4), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro (2011). 2011.20. PubMed PMID: 21460876; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3888819.

Mavros, M. N., Economopoulos, K. P., Alexiou, V. G. & Pawlik, T. M. Treatment and prognosis for patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 149 (6), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5137 (2014).

Kourou, K., Exarchos, T. P., Exarchos, K. P., Karamouzis, M. V. & Fotiadis, D. I. Machine learning applications in cancer prognosis and prediction. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 13, 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2014.11.005 (2015).

Cruz, J. A. & Wishart, D. S. Applications of machine learning in cancer prediction and prognosis. Cancer Inf. 2, 59–77 (2007). Epub 20070211. PubMed PMID: 19458758; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2675494.

Swanson, K., Wu, E., Zhang, A., Alizadeh, A. A. & Zou, J. From patterns to patients: advances in clinical machine learning for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Cell 186 (8), 1772–1791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.035 (2023).

Zhou, S. N. et al. A New Prognostic Model Covering All Stages of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Transl Hepatol. ;10(2):254 – 62. Epub 20210707. (2022). https://doi.org/10.14218/jcth.2021.00099. PubMed PMID: 35528972; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9039701.

Lv, Y. et al. A novel model for predicting the prognosis of postoperative intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 19267. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45056-9 (2023).

Raoof, M. et al. Development and validation of a prognostic score for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. JAMA Surg. 152 (5), e170117–e. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0117 (2017).

Kolasseri, A. E. Comparative study of machine learning and statistical survival models for enhancing cervical cancer prognosis and risk factor assessment using SEER data. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 22203. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72790-5 (2024).

Büttner, S. et al. Quality and performance of validated prognostic models for survival after resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB 23 (1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2020.07.007 (2021).

Shin, S. et al. Machine learning vs. conventional statistical models for predicting heart failure readmission and mortality. ESC Heart Fail. 8 (1), 106–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.13073 (2021). Epub 20201117.

Liu, J. et al. Lasso-Based machine learning algorithm for predicting postoperative lung complications in elderly: A Single-Center retrospective study from China. Clin. Interv Aging. 18, 597–606. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.S406735 (2023). Epub 20230414.

de Visser, K. E. & Joyce, J. A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: from cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell. 41 (3), 374–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2023.02 (2023). .016. PubMed PMID: 36917948.

Jin, M-Z. & Jin, W-L. The updated landscape of tumor microenvironment and drug repurposing. Signal. Transduct. Target. Therapy. 5 (1), 166. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-00280-x (2020).

Yu, X., Zhu, L., Wang, T. & Chen, J. Immune microenvironment of cholangiocarcinoma: biological concepts and treatment strategies. Front. Immunol. 14, 1037945 (2023). Epub 20230417. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1037945. PubMed PMID: 37138880; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC10150070.

Tomlinson, J. L., Valle, J. W. & Ilyas, S. I. Immunobiology of cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 79 (3), 867–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.05.010 (2023).

Fabris, L., Sato, K., Alpini, G. & Strazzabosco, M. The tumor microenvironment in cholangiocarcinoma progression. Hepatology 73 (Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 75–85 (2021). Epub 20201106. doi: 10.1002/hep.31410. PubMed PMID: 32500550; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7714713.

Wu, W. et al. Immune microenvironment infiltration landscape and immune-related subtypes in prostate cancer. Front. Immunol. 13, 1001297. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1001297 (2022). Epub 20230109.

Tie, Y., Tang, F. & Wei, Y. Wei X-w. Immunosuppressive cells in cancer: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. J. Hematol. Oncol. 15 (1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-022-01282-8 (2022).

Job, S. et al. Identification of four immune subtypes characterized by distinct composition and functions of tumor microenvironment in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 72 (3), 965–981. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31092 (2020). Epub 20200816.

Ahn, K. S. et al. Prognostic subclass of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by integrative molecular-clinical analysis and potential targeted approach. Hepatol. Int. 13 (4), 490–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-019-09954-3 (2019). Epub 20190618.

Cai, W. Y. et al. Identification of a tumor Microenvironment-relevant gene set-based prognostic signature and related therapy targets in gastric cancer. Theranostics 10 (19), 8633–8647. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.47938 (2020). Epub 20200709.

Tang, Y., Guo, C., Chen, C. & Zhang, Y. Characterization of cellular senescence patterns predicts the prognosis and therapeutic response of hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 1100285 (2022). Epub 20221216. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.1100285. PubMed PMID: 36589233; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9800843.

Wang, L. et al. CXCL17 promotes cell metastasis and inhibits autophagy via the LKB1-AMPK pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gene 690, 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2018.12.043 (2019).

Li, L. et al. CXCL17 expression predicts poor prognosis and correlates with adverse immune infiltration in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 9 (10), e110064. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110064 (2014). Epub 20141010.

Shin, H. J., Gil, M. & Lee, I. S. Association of Elevated Expression Levels of COL4A1 in Stromal Cells with an Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment in Low-Grade Glioma, Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Skin Cutaneous Melanoma, and Stomach Adenocarcinoma. J Pers Med. ;12(4). Epub 20220328. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12040534. PubMed PMID: 35455650; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9029283.

Kim, H. S. et al. Tumor endothelial Cells-Associated integrin Alpha-6 as a promising biomarker for early detection and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 15 (16). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15164156 (2023). Epub 20230817.

Lin, H. et al. Stanniocalcin 1 is a phagocytosis checkpoint driving tumor immune resistance. Cancer Cell. ;39(4):480 – 93.e6. Epub 20210128. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2020.12.023. PubMed PMID: 33513345; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8044011.

Huang, P. et al. Construction and Validation of a Tumor Microenvironment-Based Scoring System to Evaluate Prognosis and Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Lung Adenocarcinoma Patients. Genes (Basel). ;13(6). Epub 20220526. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13060951. PubMed PMID: 35741714; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9222903.

Thorsson, V. et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity. ;48(4):812 – 30.e14. Epub 20180405. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.023. PubMed PMID: 29628290; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5982584.

Finley, D. S., Pantuck, A. J. & Belldegrun, A. S. Tumor biology and prognostic factors in renal cell carcinoma. Oncologist 16 (Suppl 2(Suppl 2), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2011-S2-04 (2011). PubMed PMID: 21346035; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3868202.

Park, J. et al. Transcriptome profiling-based identification of prognostic subtypes and multi-omics signatures of glioblastoma. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 10555. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47066-y (2019).

Wang, T. et al. COL4A1 promotes the growth and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by activating FAK-Src signaling. J. Experimental Clin. Cancer Res. 39 (1), 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-020-01650-7 (2020).

Jin, R. et al. The highly expressed COL4A1 genes contributes to the proliferation and migration of the invasive ductal carcinomas. Oncotarget 8 (35), 58172–58183. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.17345 (2017). Epub 20170421.

Tian, X., Sun, J., Li, C. & Zhang, K. COL4A1 promotes the proliferation and migration of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells by binding to NID1. Exp. Ther. Med. 25 (4), 176. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2023.11875 (2023). Epub 20230307.

Brooks, D. L. P. et al. ITGA6 is directly regulated by hypoxia-inducible factors and enriches for cancer stem cell activity and invasion in metastatic breast cancer models. Mol. Cancer. 15 (1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-016-0510-x (2016).

Wu, Y. et al. ITGA6 and RPSA synergistically promote pancreatic cancer invasion and metastasis via PI3K and MAPK signaling pathways. Exp. Cell Res. 379 (1), 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.03.022 (2019).

Wei, L., Yin, F., Chen, C. & Li, L. Expression of integrin α–6 is associated with multi drug resistance and prognosis in ovarian cancer. Oncol. Lett. 17 (4), 3974–3980. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2019.10056 (2019).

Khademi, R. et al. Regulation and Functions of α6-Integrin (CD49f) in Cancer Biology. Cancers (Basel). ;15(13). Epub 20230702. (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15133466. PubMed PMID: 37444576; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC10341356.

Lin, F. et al. Stanniocalcin 1 promotes metastasis, lipid metabolism and cisplatin chemoresistance via the FOXC2/ITGB6 signaling axis in ovarian cancer. J. Experimental Clin. Cancer Res. 41 (1), 129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-022-02315-3 (2022).

Liu, A. et al. Stanniocalcin 1 promotes lung metastasis of breast cancer by enhancing EGFR–ERK–S100A4 signaling. Cell Death Dis. 14 (7), 395. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-023-05911-z (2023).

Tamura, S. et al. Clinical significance of STC1 gene expression in patients with colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 31 (1), 325–329 (2011). PubMed PMID: 21273618.

Hayashi, M. et al. GULP1 regulates the NRF2-KEAP1 signaling axis in urothelial carcinoma. Sci Signal. ;13(645). Epub 20200818. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.aba0443. PubMed PMID: 32817372.

Maldonado, L. et al. Integrated transcriptomic and epigenomic analysis of ovarian cancer reveals epigenetically silenced GULP1. Cancer Lett. 433, 242–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2018.06.030 (2018).

Hiraoka, N. et al. CXCL17 and ICAM2 are associated with a potential Anti-Tumor immune response in early intraepithelial stages of human pancreatic carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 140 (1), 310–21e4. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.009 (2011).

Qian, X. et al. COL4A1 promotes gastric cancer progression by regulating tumor Invasion, tumor microenvironment and drug sensitivity. Curr. Med. Chem. (2025). Epub 20250407. doi: 10.2174/0109298673351943250314074632. PubMed PMID: 40197201.

Yang, Y., Yin, S., Li, S., Chen, Y. & Yang, L. Stanniocalcin 1 in tumor microenvironment promotes metastasis of ovarian cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 12, 2789–2798. https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.S196150 (2019). Epub 20190411.

Jacenik, D., Karagiannidis, I. & Beswick, E. J. Th2 cells inhibit growth of colon and pancreas cancers by promoting anti-tumorigenic responses from macrophages and eosinophils. Br. J. Cancer. 128 (2), 387–397. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-02056-2 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Pharmaceutical targeting Th2-mediated immunity enhances immunotherapy response in breast cancer. J. Translational Med. 20 (1), 615. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-022-03807-8 (2022).

Kronenberg, M. & Engel, I. NKT cells in the antitumor response: the β version? J. Clin. Invest. 134(4), e177663. (2024). Epub 20240215. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci177663. PubMed PMID: 38357925; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC10866647.

Zhang, X. et al. Double-edged effects of interferons on the regulation of cancer-immunity cycle. Oncoimmunology 10 (1), 1929005. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402x.2021.1929005 (2021). Epub 20210630.

Oliviero, B. et al. MICA/B-targeted antibody promotes NK cell-driven tumor immunity in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Oncoimmunology 11 (1), 2035919 (2022). PubMed PMID: 35223192; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8865231.

Jung, I. H. et al. Vivo study of natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity against cholangiocarcinoma in a nude mouse model. Vivo 32 (4), 771–781 (2018). PubMed PMID: 29936458; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6117784.

Karpisheh, V. et al. The role of Th17 cells in the pathogenesis and treatment of breast cancer. Cancer Cell. Int. 22 (1), 108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-022-02528-8 (2022). Epub 20220305.

Sun, X. et al. CD39/ENTPD1 expression by CD4 + Foxp3 + regulatory T cells promotes hepatic metastatic tumor growth in mice. Gastroenterology 139 (3), 1030–1040. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.007 (2010). Epub 20100625.

Feng, L. et al. Vascular CD39/ENTPD1 directly promotes tumor cell growth by scavenging extracellular adenosine triphosphate. Neoplasia 13 (3), 206–IN2. https://doi.org/10.1593/neo.101332 (2011).

Liu, S., Zhang, J., Zhu, J., Jiao, D. & Liu, Z. Prognostic values of EDNRB in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncol. Lett. 20 (5), 149 (2020). Epub 20200824. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.12012. PubMed PMID: 32934717; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7471672.

Zhang, L. et al. The clinical significance of endothelin receptor type B in hepatocellular carcinoma and its potential molecular mechanism. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 107, 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexmp.2019.02.002 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the funding support from the Startup Fund for Scientific Research of Fujian Medical University, Sanming City Science and Technology Plan Project, Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, Joint funds for the innovation of science and technology of Fujian Province, Quanzhou High-level Talent Project.

Funding

This study was funded by the Startup Fund for Scientific Research, Fujian Medical University (2022QH1110), Sanming City Science and Technology Plan Project (2023-S-105), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2024J01665), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2024J01678), Joint funds for the innovation of science and technology, Fujian Province (2024Y9383), Joint funds for the innovation of science and technology, Fujian Province (2024Y9384), Quanzhou High-level Talent Project (2021C048R).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DYX, HTL and XQM performed all the experiments and all the bioinformatics analyses of the article, wrote the manuscript. YMS visualized the data. WW and LPW conceived and designed the manuscript, provided methodological support. DYX, HTL and LPW provided financial support.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted following the guidelines and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University (No.194[2023]).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, D., Lin, H., Ma, X. et al. A novel tumor microenvironment-related gene signature for prognostic prediction of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 41570 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25463-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25463-w