Abstract

In the maintenance of transportation infrastructure, crack segmentation is critical for ensuring road safety and prolonging the service life of bridges and other facilities. Existing methods struggle with complex background interference and intricate crack morphologies (e.g., mesh-like or tree-like morphologies). Meanwhile, high-precision models frequently suffer from excessive computational costs. To address these limitations, this study proposes, a lightweight crack segmentation network based on an Importance-Enhanced Mamba model. Built upon the U-Net architecture, innovatively features a dual-branch design that integrates CNN and Mamba modules for synergistic feature extraction. Within the Mamba branch, we designed an importance-enhanced dynamic scanning module, which adaptively adjusts scanning paths according to actual crack geometries, thereby significantly enhancing the perception of global key crack features. Concurrently, the CNN branch specializes in capturing fine-grained local features such as edges and textures. These complementary features are fused via an attention-guided module, which assigns adaptive weights to enable pixel-wise integration of local and global information, thus preserving both microstructural details and macroscopic relationships of crack. Comprehensive experiments conducted on three public datasets (Crack500, CrackTree260, and CrackForest) demonstrate that outperforms other advanced methods in segmentation accuracy while achieving significant reductions in model parameters and computational complexity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In modern transportation infrastructure construction and maintenance, crack detection serves as a pivotal task for safeguarding road safety and enhancing structural durability. Timely and precise identification of cracks in key facilities such as bridges and roads plays a critical role in rationalizing maintenance scheduling, extending service life, and elevating driving safety1,2. Traditional detection approaches have primarily relied on manual visual inspection, a method fraught with inherent limitations, including substantial labor intensity, prolonged detection cycles, and non-uniform detection outcomes stemming from variations in subjective judgment. These drawbacks collectively render traditional methods inadequate for meeting the operational and maintenance demands of large-scale infrastructure projects3.

With the advancement of automation technology, image processing methods such as edge detection and texture feature analysis have been widely applied in crack detection tasks4. However, the segmentation performance of these traditional approaches depends strongly on the calibration of predefined parameters, leading to significant generalization constraints in complex environments (e.g., uneven lighting and texture interference). Leveraging breakthroughs in deep learning and computer vision, automated crack detection has achieved transformative progress5,6,7. For example, Zhong et al.8 proposed a lightweight dual-encoder framework with cross-feature fusion mechanisms to improve detection accuracy. Additionally, Quan et al.9 integrated transformer architectures into their pipelines, enabling high-precision crack segmentation even in challenging operational scenarios. Even with the progress mentioned earlier, current models continue to encounter difficulties regarding segmentation efficiency. In particular, crack segmentation methods based on the Transformer architecture often have a large number of parameters. Therefore, deploying these models in scenarios with limited computing resources becomes extremely difficult.

In contrast, the Mamba model has gained widespread application in medical image processing due to its significant advantage of linear computational complexity10. Additionally, it can effectively establish long-range dependencies through a state space model (SSM), which is crucial for segmentation tasks involving dense predictions. However, the Mamba model typically employs a static scanning method, performing sequential scans only in horizontal or vertical directions. This approach struggles with irregular complex shapes such as tree-like or network-like structures, limiting Mamba’s performance in crack segmentation tasks.

To achieve an optimal balance between computational resource consumption and segmentation accuracy, we draw inspiration from previous related studies11,12,13 and propose a lightweight crack segmentation network based on the importance-enhanced Mamba model—IEM-UNet. Specifically, IEM-UNet adopts the symmetric encoder-decoder architecture of U-Net as its backbone network, and innovatively uses a dual-branch module that combines convolutional neural networks (CNN) and Mamba as a hybrid feature extraction unit. In the Mamba branch, we designed an importance-enhanced dynamic scanning module that adaptively adjusts the scanning path based on the actual crack shape, enhancing the model’s sensitivity to critical crack regions. Additionally, we employed the SSM module to establish contextual dependencies of cracks, significantly improving the model’s perception of global critical crack features. The CNN branch is used to extract fine-grained local features, such as crack edges and textures. To further enhance segmentation performance, a multi-scale feature aggregation module is introduced to integrate local and global information, ultimately achieving precise and fast crack segmentation. In summary, the contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

(1)

We introduce a lightweight crack segmentation network based on the Importance-Enhanced Mamba model. Extensive experimental results on three public datasets demonstrate that IEM-UNet not only attains segmentation accuracy on par with or even surpassing that of other advanced models, but also effectively manages to keep the model size and computational complexity in check.

-

(2)

We propose a novel dynamic scanning strategy grounded in importance-enhancement, which effectively overcomes the limitations of traditional sequential scanning methods in accommodating complex, variable crack morphologies.

-

(3)

We introduce a dual-branch architecture integrating CNN and Mamba, which facilitates effective extraction of fine-grained local features and global features of cracks. Moreover, we embed a multi-scale feature integration module to merge these features, thus further boosting segmentation performance.

Related work

Within the realm of computer vision, CNNs have found extensive use in crack segmentation tasks14,15. As a classic segmentation architecture, U-Net16 has laid a robust foundation for subsequent research. U-Net++17 incorporates a nested skip connection mechanism to further enhance segmentation accuracy. DeepCrack18 effectively integrates multi-level features via a multi-scale feature fusion mechanism, enabling pixel-level crack segmentation. CrackSegAN19 innovatively introduces an elastic deformation data augmentation strategy, which enhances model stability under complex background interference. Furthermore, to mitigate the gradient vanishing problem in traditional U-Net architectures, RUC-Net20 restores feature propagation paths through residual connections, thereby improving the training stability of deep networks.

Nonetheless, CNNs have an inherent limitation in their ability to capture long-range dependencies because of their localized receptive fields. This limitation is particularly detrimental to dense prediction tasks such as object segmentation, where global contextual information is critical for accurately identifying object boundaries and maintaining the topological consistency of segmentation results21. In comparison, the Transformer architecture utilizes self-attention mechanisms to effectively create global pixel-level dependencies, which greatly improves the topological accuracy of crack modeling due to its strong contextual understanding22,23. CrackFormer24 first achieved cross-channel global information extraction, with subsequent work25 subsequently refining this methodology. FAT-Net26 pioneered a feature-adaptive Transformer module, whereas DTrC-Net27 further optimized intermediate-level feature fusion within this framework. PCTNet28 introduced a dual-attention network and conducted a systematic study on the impact of camera pose on detection performance. TransUnet29 improves segmentation accuracy and efficiency by introducing a self-attention mechanism and global context information transfer. SwinCrack30 achieves adaptive spatial aggregation through Swin-Transformer blocks, enabling more accurate and continuous modeling of cracks.

While the self-attention mechanism in Transformer models allows for the creation of global contextual relationships, its computational complexity increases quadratically with the size of the image.. This incurs substantial computational overhead and memory consumption when processing high-resolution images31,32, thereby posing significant challenges to their practical deployment in resource-constrained scenarios. Consequently, researchers have been exploring efficient alternatives to Transformer models. The Mamba model, which is based on the state space model (SSM), has gained significant interest because of its benefit of linear computational complexity33. It was initially applied to medical image segmentation tasks34,35. Chen et al.36 later pioneered the visual Mamba framework, which effectively establishes global dependencies in crack segmentation while significantly enhancing computational efficiency compared to Transformer architectures. Qi et al.37 further proposed the Channel Parallel Mamba Module (CPM), which decomposes input images along channel dimensions and processes them in parallel via Mamba to further optimize runtime efficiency.

While Mamba demonstrates remarkable advantages in computational efficiency, traditional static scanning mechanisms (horizontal or vertical) struggle to effectively adapt to the intricate crack structures. This gives rise to segmentation inaccuracies in regions featuring blurred boundaries and small crack branches, thereby resulting in a reduction in segmentation accuracy.

Proposed method

We propose IEM-UNet, a lightweight crack segmentation network grounded in the importance-enhanced Mamba model. This framework adds a dynamic scanning module to the original Mamba model and combines it with a CNN network to form a dual-branch structure. This enables accurate segmentation of complex cracks while significantly improving computational efficiency. In this section, we first elaborate on the fundamental concepts and principles of Mamba. We then provide an overview of the IEM-UNet framework, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. Finally, we elaborate on each key component of the framework.

Preliminaries

As a novel neural architecture grounded in the state-space model (SSM), Mamba exhibits remarkable advantages in modeling long-range temporal dependencies. Its core resides in the dynamic modeling of sequence information via continuous-time state-space equations. Moreover, its computational complexity scales linearly, maintaining efficiency even for large input sequences. Formally, the fundamental SSM equation is defined as follows:

where x(t)∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) L and y(t)∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) L represent continuous input and output sequences, respectively, where L denotes the sequence dimension. h(t)∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) N represents the hidden state vector, and N denotes its length. A, B, C, D represent parameter matrices.

Similar to the attention mechanism, the Selective State Space Model (S6) assumes that all input data x have different levels of importance for the output result y. Therefore, S6 further extends SSM by using the input sequence to initialize the parameter matrix. B and C are initialized directly using the linear projection of the input sequence.

where Linear denotes linear projection. Mamba combines SMM and S6. This allows for varying degrees of attention to be paid to the input sequence during training, thereby filtering out irrelevant information and retaining more important information.

However, for discrete input signals, the zero-order hold (ZOH) technique is leveraged to convert them into continuous signals compatible with SSM. Specifically, for a discrete time step k, the input sequence is transformed into a piecewise constant signal by holding the current value constant until the next sampling instant. This discrete-to-continuous mapping mechanism renders SSM compatible with the grid structure of images. The mathematical formulation for this discrete-to-continuous conversion is given as:

where ∆∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) L represents the learnable time step parameter, which is one of the core parameters of Mamba, and I represents the identity matrix.

IEM-UNet

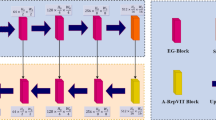

The network architecture of IEM-UNet is depicted in Fig. 1(a). This network adopts the symmetric encoder-decoder framework of U-Net, comprising three core components: an encoder, a decoder, and a bottleneck layer.

The encoder comprises an initial layer and four cascaded processing blocks. Given an input image I ∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) H×W×C, where H, W, and C represent the height, width, and number of channels of the input image, respectively. The initial layer employs DepthWise convolution (DW-conv) to extract low-level features FL ∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) H×W×32 from the input image I, thereby retaining edge and texture details of the target to be segmented. Subsequently, a four-layer cascaded structure is employed, with each layer containing two IE-VSS modules and one Down-Sampling module. The IE-VSS module functions as the primary unit for feature extraction, aimed at capturing long-range relationships between objects in the image.

The Down-Sampling module employs max pooling operations to reduce the spatial resolution of feature maps. Subsequently, the feature map undergoes sequential processing through 1 × 1 convolutions, normalization, and the SiLU activation function, doubling the number of feature channels.

After each processing step, the feature map resolution halves and the number of channels doubles. The feature map dimensions evolve sequentially as \(\frac{H}{2}\times \frac{W}{2}\times 64\), \(\frac{H}{4}\times \frac{W}{4}\times 128\), \(\frac{H}{8}\times \frac{W}{8}\times 256\), \(\frac{H}{16}\times \frac{W}{16}\times 512\). Finally, deep semantic feature encoding is achieved via a single IE-VSS module in the bottleneck layer.

The decoder adopts a mirrored architecture symmetric to the encoder, with its core being the restoration of spatial detail information through a multi-level skip connection mechanism. Each cascaded structure within the decoder comprises two IE-VSS modules and one Up-Sampling module. Transposed convolution is used for Up-Sampling, increasing the resolution of the feature map by two times while reducing the number of channels by half. Subsequently, unsampled features are concatenated along the channel axis with the corresponding encoder—layer features and fed into the IE-VSS module for feature calibration.

Importance-enhanced visual state space model (IE-VSS)

The IE-VSS module, a parallel fusion architecture integrating CNN and Visual State Space (VSS) (as illustrated in Fig. 1(b)), achieves synergistic extraction of local and global information through a dual-branch parallel design. The CNN branch (left) employs 3 × 3 DepthWise convolutions to construct lightweight convolutional modules, which sequentially extract texture, edge, and other fine-grained details from the spatial neighborhood of cracks, generating local features F1 ∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) h×w×c. The right branch of the module is a improved VSS component used to extract global features F2 ∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) h×w×c from images. The AG Modules is a feature fusion module based on the attention mechanism. It is used to better fuse the local features F1 obtained by CNN and the global features F2 obtained by the improved VSS component.

Importance-enhanced scan (IE-scan)

Most existing Mamba architectures employ fixed horizontal-vertical scanning paths, a static strategy that is inconsistent with the spatial anisotropy of cracks. Specifically, real-world cracks often exhibit irregular tree-like branching or mesh-like topological patterns, whereas the predetermined scanning paths of the SS2D module fail to adaptively align with these dynamically changing geometric features. More critically, this static strategy may perform unnecessary processing on non-crack regions, exacerbating background interference and thereby compromising segmentation accuracy.

To address these limitations, we developed a dynamic scanning strategy with Importance-Enhanced (IE-scan). Instead of applying uniform processing across all spatial locations, our approach dynamically filters key regions containing crack features to reconstruct the scanning path.

Specifically, inspired by recent advancements in medical image segmentation38,39, they emphasized the importance of differentiating key target features to enhance segmentation accuracy. Therefore, we attempt to explore dynamically adjusting the image scanning order based on differences in feature importance. Intuitively, this should enhance the model’s adaptability to the irregular shapes of cracks. Furthermore, according to the Class Activation Mapping (CAM) theory40, in a neural network, the activation magnitude reflects the extent to which a neuron responds to input features. Regions with high activation magnitudes typically contain more discriminative information relevant to the task objective. Therefore, we adopt activation intensity as a measure of feature importance.

Consistent with the traditional Mamba model processing method, assume that the feature F∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) h×w×c uniformly divided into n rows and n columns, resulting in N non-overlapping blocks \({f}_{i}\in {\mathbb{R}}\) p×q×c, where i ∈ [1,N], \(p=\frac{h}{n}\), \(q=\frac{w}{n}\). The importance of feature blocks \({f}_{i}\) is calculated as follows:

where, \({\Gamma }_{\text{act}}(\bullet )\) represents the importance of the feature block \({f}_{i}\), p and q represent the length and width of feature block \({f}_{i}\), and \({f}_{i}(j,k)\) represents the sum of the values across all channels in the i-th row and j-th column of the feature block \({f}_{i}\), respectively. This reflects the response intensity and distribution across all channels in the spatial dimension, while also indicating the relevance of this feature block to the segmentation task.

We sort all feature blocks in descending order based on their corresponding importance scores, thereby generating a dynamic scanning sequence.

where, \({Scan}_{idx}\) denotes the dynamic scanning sequence derived based on importance.

As shown in Fig. 2, when using a static scanning strategy, the sequence of feature blocks obtained remains fixed. For example, if sequential scanning is performed horizontally, the resulting sequence is {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9}. If sequential scanning is performed vertically, the sequence obtained is {1,4,7,2,5,8,3,6,9}. However, when employing a descending-order scanning method based on importance, the sequence obtained in the example of Fig. 2 could be {4,6,1,5,8,…}. Such scanning sequences can be dynamically adjusted according to the crack morphology.

Improved VSS component

The structure of the improved VSS component is shown in the dotted box in Fig. 1(b). First, input features undergo layer normalization, adjusting the input data to a standard distribution with a mean of 0 and variance of 1. Subsequently, in the first path, feature maps sequentially pass through a linear layer, a deep convolutional layer with SiLU activation, an SS2D module, and layer normalization.

The structure of SS2D is depicted in Fig. 3. To enhance the model’s capability to characterize key semantic regions, importance-enhanced dynamic scanning strategy is employed during the scanning phase, which adaptively adjusts spatial sampling priorities to emphasize salient regions. An input sequence X(t), t ∈ {1} is obtained through IE scan. As shown in Fig. 1(a), the IE-VSS module is employed across four levels of the IEM-UNet encoder. The \(\text{p}\times \text{q}\) (hyperparameters) for the IE-Scan process in each level is set sequentially from top to bottom as \(16\times 16\), \(8\times 8\), \(4\times 4\), and \(2\times 2\), with identical \(\text{p}\times \text{q}\) values across the two IE-VSS modules in each level. The decoder section corresponds layer-by-layer to the encoder.

Additionally, to preserve both horizontal and vertical crack features, the cross-scan method from the base Mamba model is retained. Specifically, cross-scan involves sequential scanning along the horizontal and vertical directions of the input feature map, yielding a total of four input sequences X(t), t ∈ {2,3,4,5}. This branch integrates both scanning strategies (IE-scan and Cross-scan) to enhance the network’s adaptability to complex crack morphologies.

For each input sequence X(t), a shared-weight S6 module is used to model long-range dependencies, thereby generating the output sequence Y(t). Specifically, the projection matrices B and C, along with parameters such as A and D, are shared across time steps within each sequence. For a single sequence, the same set of parameters is used across all time steps. However, weights are not shared between different sequences. Each sequence possesses an independent set of parameters. Without the weight sharing mechanism, each time step would have its own distinct parameters. This would directly lead to an explosion in model parameters, contradicting Mamba’s lightweight nature. Moreover, this approach cannot generalize to sequence lengths not encountered during training.

Then, an inverse scan operation is performed on each output sequence Y(t), restoring it to its initial structure in reverse scan order. Finally, the five restored structures are merged by summation. The merged feature map undergoes layer normalization processing once more. It is worth noting that the computational pipeline of this module maintains linear complexity throughout the entire process, ensuring high computational efficiency. As shown in Table 1, we have used pseudocode to further detail the computational process of SS2D.

The second path adopts a simplified processing pipeline, transforming features solely via a linear projection layer with an activation function. Finally, the output feature maps from both paths are element-wise multiplied to generate global features F2 ∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) h×w×c.

Attention-gated (AG) module

The local features extracted by the CNN branch excel at capturing fine details of cracks but are prone to incorporating irrelevant textures, artifacts, and other background noise. Conversely, the global features obtained by the improved Mamba model effectively compensate for the shortcomings of local features in extracting the overall structure and spatial relationships of cracks. It is important to note that indiscriminate fusion of these two feature types may dilute or even obscure core features due to redundant information, thereby compromising the model’s segmentation performance.

To realize the effective fusion of local feature F1 and global feature F2, an Attention-Gated (AG) module is constructed, as shown in Fig. 4. By automatically assigning feature weights, the fusion ratio of local and global features is controlled pixel-wise to better preserve the crack detail information and global relationship.

Specifically, F1 and F2 first concatenated along the channel dimension to obtain the feature Fconcat ∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) h×w×2c. Then, the number of channels is compressed by 3 × 3 Conv to generate the intermediate feature F3 ∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) h×w×c. In the channel branching, the intermediate feature F3 is subjected to the Global Average Pooling (GAP) to generate the channel descriptor, and sequentially connect the fully connected layers and the Sigmoid function to generate the channel weight ω1 ∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) 1×1×c. In the spatial branch, a 3 × 3 convolution is performed on the intermediate feature F3, and the Sigmoid function is connected to generate the spatial weight ω2 ∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) h× w×1. The weights ω1 and ω2 obtained from the channel branch and the spatial branch are multiplied together to obtain the joint attention weight ωf ∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) h×w×c. Finally, local and global features are fused based on the joint attention weight ωf:

where Ffusion ∈\({\mathbb{R}}\) h×w×c denotes the fused features.

Experiments

Dataset

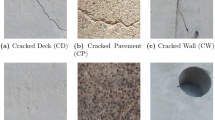

To ensure the reliability and comprehensiveness of the experiment, we employed three publicly available crack segmentation datasets for testing and evaluation—specifically Crack50041, CrackTree26042, and CrackForest43. These datasets encompass a variety of challenging samples, including different lighting conditions, shadow interference, similar background interference, complex crack morphology, and fine cracks.

Crack500 encompasses images gathered from road surfaces constructed with diverse materials, such as asphalt and concrete. These images capture a wide spectrum of lighting conditions and crack degradation levels, and are accompanied by highly accurate pixel-wise semantic annotations. The Crack500 dataset was randomly divided into a training set and a test set, containing 2,244 and 1,124 images, respectively.

CrackTree260 and CrackForest consist of 260 and 118 images with pixel-wise annotations, respectively. Primarily, these datasets feature images of small cracks and those with intricate background noise. Given the modest size of these two datasets, we combined them into a unified dataset and standardized the image dimensions to eradicate resolution disparities. As shown in Fig. 5, to reduce the risk of overfitting caused by the limited number of images and improve the network’s generalization performance, we enhanced the original data by reducing image brightness, adding Gaussian noise, rotating, and cropping the images. We named the merged and enhanced dataset Crack756, which consists of 529 training samples and 227 test samples.

Evaluation indicators

In line with related work in the field1, We assess the model’s segmentation accuracy performance using four metrics: Precision, Recall, F1, and mIoU. Furthermore, we assess the model’s efficiency by considering the number of parameters and the floating-point operations per second (FLOPs):

where TP, FP, and FN represent true positive, false positive, and false negative, respectively.

Experimental setup

The project was implemented using Python 3.11 and the PyTorch 2.3.1 deep learning framework. For the training process, the Adam optimizer was deployed with an initial learning rate set to 0.01, a batch size of 2, and a total of 150 training epochs. Detailed configurations are outlined in Table 2:

Analysis of experiments results

The training loss curves for the proposed method and the comparison methods are shown in Fig. 6. (a) shows the loss curve on Crack500, and (b) shows the loss curve on Crack756. All models tend to stabilize after approximately 50 epochs of training. As shown in Fig. 6, our method achieves smaller training losses on both datasets.

Results on the Crack500

We first evaluated the segmentation performance of various models on the Crack500 dataset, which comprises a large number of highly challenging segmentation instances. These instances place higher demands on the segmentation capabilities of the models, and the results are presented in Table 3.

Compared to models based on Mamba and Transformer architectures, CNN-based models generally performed less well. Among these, DeepCrack improved the F1-score to 68.37% via multi-scale fusion techniques. However, the inherent limitations of CNNs in modeling global context hinder further improvements in segmentation performance when dealing with complex background interference.

Among Transformer-based models, SwinCrack effectively captures long-range dependencies through self-attention mechanisms and achieves the highest Precision (73.38%). Nevertheless, IEM-UNet excels across all models in overall performance: it outperforms all other models in three key metrics—Recall, F1-score, and mIoU—with values of 73.45%, 73.01%, and 72.93% respectively. Moreover, compared to other Mamba-based models, IEM-UNet yields performance gains of at least 2.29%, 0.74%, 0.88%, and 1.02% across the four metrics.

Results on the Crack756

The performance evaluation results on the Crack756 dataset are shown in Table 4. The IEM-UNet model delivered outstanding results across four key metrics: Precision (82.64%), Recall (81.53%), F1-score (81.615%), and mIoU (80.47%). Notably, IEM-UNet exhibited exceptional performance in Recall and mIoU, outperforming all comparative models by at least 1.06% and 0.7%, respectively. While it did not claim the top spot in Precision and F1-score—where the SwinCrack model achieved the highest values of 83.81% and 81.73%, respectively—IEM-UNet still secured second place through its robust performance.

The performance enhancement serves as unequivocal evidence of the efficacy of the importance-enhanced dynamic scanning strategy employed in IEM-UNet. This sophisticated strategy is designed to autonomously adapt the scanning sequence in accordance with the unique characteristics of cracks. It excels in accentuating critical crack information while robustly suppressing interference from background noise. When synergistically combined with the local detail extraction capabilities of CNNs, it substantially bolsters the segmentation performance.

Computational efficiency analysis

Regarding computational efficiency, this study conducted experiments on the Crack756 dataset. The corresponding experimental results are presented in Table 5. On the one hand, models based on the Mamba architecture are significantly more efficient than those based on CNN and Transformer architectures. Focusing on two key efficiency metrics—the number of parameters and the number of floating-point operations (FLOPs)—the Mamba series models outperform traditional architectures. On the other hand, IEM-UNet, with only 10.6 M parameters and 6.2 G FLOPs, achieves the best performance among all tested models. Compared with other models, the number of parameters and FLOPs are improved by at least 30.26% and 27.06% respectively.

Although we did not achieve the best performance in terms of a certain segmentation accuracy metric, this represents the inevitable trade-off between model simplicity and segmentation accuracy. Extensive experimental evaluations clearly show that our method achieves a good balance between these key aspects.

Visualization results.

The notable disparities in performance among various methods become conspicuous in the crack segmentation task within complex scenes. We selected segmentation results from several complex samples for visual analysis, as depicted in Fig. 7.

In the first row of the figure, when encountering interference from abnormal objects like manhole covers, traditional methods predominantly manifest detection omissions and disruptions in the topological structure of dense crack regions (highlighted by the yellow box). The images in Rows 2 and 3 show samples with similar background interference. When the background contains interfering elements highly similar to cracks, the false detection rate of crack edge detail segmentation increases significantly. The images in Rows 4 and 5 respectively present samples with lane line interference and samples under normal environments. The images in Row 6 display segmentation results with shadow interference. For other segmentation models, when crack edges overlap with shadow edges, errors such as discontinuous segmentation tend to occur in the overlapping areas, which leads to a decrease in segmentation accuracy.

In contrast, our proposed method effectively extracts both local and global features of cracks through CNN and Mamba fusion, successfully restoring more comprehensive crack details while ensuring good continuity. It outperforms traditional counterparts in these challenging scenarios.

Ablation experiment

In order to evaluate the individual impact of the IE-Scan, CNN module, and feature fusion modules (AG Modules) on the overall performance of the model, we designed six ablation experiments on the Crack500 dataset. The experimental results are shown in Table. 6.

Compared to the initial Mamba model (Scheme ①), the improved model (Scheme ②) incorporating the proposed IE-Scan module achieves varying degrees of enhancement across multiple performance metrics. Specifically, both Precision and Recall witnessed substantial improvements, unequivocally validating the module’s efficacy in mitigating false positives and false negatives. Moreover, F1 and mIoU increased by 2.56% and 3.67%, respectively, demonstrating that the importance scanning strategy endows the model with heightened sensitivity to global key features.

Building upon Scheme ②, Scheme ③ further incorporates a CNN branch for local feature extraction. We fuse local and global features by concatenating them along the channel dimension. On one hand, experiments comparing Scheme ② and Scheme ③ demonstrate that the CNN branch enhances segmentation performance.

On the other hand, to evaluate the effectiveness of the feature fusion strategy, we replaced the channel concatenation fusion method in Scheme ③ with the feature fusion approach adopted in this paper (labeled as Scheme ⑥). The comparison results demonstrate that Approach 6 achieves higher segmentation accuracy than Approach 3, intuitively proving the effectiveness of the feature fusion method proposed in this paper.

Furthermore, in Scheme ⑤, we directly added local and global features for fusion. Compared to Scheme ⑤, Scheme ④ achieved improvements of 2.64%, 0.59%, 1.21%, and 1.70% across four key metrics. These experiments collectively validate the significant advantages of our feature fusion strategy from multiple dimensions.

Discussion

Extensive experiments across three public datasets demonstrate that IEM-UNet achieve segmentation accuracy on par with other advanced models while maintaining a lightweight architecture. The Mamba module’s strength lies in its exceptional capabilities to model long-range dependencies, which is advantageous for dense prediction tasks like crack segmentation. However, real-world cracks exhibit irregular morphologies (e.g., tree-like or mesh-like structures), rendering Mamba’s conventional horizontal or vertical sequential scanning suboptimal. To address this, IEM-UNet introduces an importance-enhanced dynamic scanning mechanism, which can adaptively adjust the scanning order based on crack features instead of relying solely on a fixed scanning method. Nevertheless, relying solely on Mamba to capture detailed information about cracks poses a certain challenge. Thus, we reintroduce CNN. CNN supplies supplementary local features to enhance IEM-UNet’s segmentation accuracy for cracks.

Nonetheless, IEM-UNet’s element-wise adaptive fusion module incurs additional computational overhead. Future work will focus on designing more efficient fusion modules or exploring lightweight alternatives to further optimize the framework’s computational efficiency without compromising accuracy.

Conclusion

To address the issue that traditional Mamba models struggle to adapt to the complex morphology of cracks, resulting in reduced segmentation accuracy in intricate scenarios, and the high computational costs associated with conventional methods, we propose a lightweight crack segmentation network, IEM-UNet. This network delivers effective improvements in crack detection accuracy while achieving significant reductions in model parameters by optimizing the scanning path of the Mamba model and enhancing mechanisms for extracting and fusing global and local features. Experimental validation on three public datasets (Crack500, CrackTree260, CrackForest) demonstrates that IEM-UNet achieves state-of-the-art segmentation accuracy while reducing model parameters by 23.68% compared to comparable methods, showcasing its superiority in both precision and efficiency. Therefore, the following conclusions are drawn:

-

(1)

The proposed importance-enhanced dynamic scanning mechanism effectively helps the model perceive the complex morphology of cracks, thereby enhancing its ability to capture global features.

-

(2)

The fusion structure of CNN and improved Mamba can more efficiently extract fine-grained local features of cracks and organically combine them with global context modeling. These feature components are fused through a pixel-level adaptive weight module, achieving efficient integration of multi-scale features. This will effectively enhance the model’s segmentation performance for complex cracks and promote the further deployment and application of this model on mobile devices.

Future research will focus on three primary directions: (1) further exploring Mamba-based architectures to handle complex scenarios such as occlusion and variable lighting conditions; (2) constructing large-scale, high-precision crack datasets with diverse environmental backgrounds to enhance model generalization; and (3) optimizing IEM-UNet for edge computing deployment to enable real-time infrastructure inspection in resource-constrained settings. These extensions aim to solidify the practical utility of the proposed framework in real-world transportation infrastructure maintenance.

Data availability

The data used in this study can be obtained from the corresponding authors.

References

Wang, X. et al. ASARU-Net: Superimposed U-Net with residual squeeze-and-excitation layer for road crack segmentation. J. Electron. Imaging 32, 023040–023040. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JEI.32.2.023040 (2023).

Ai, D., Jiang, G., Lam, S.-K., He, P. & Li, C. Computer vision framework for crack detection of civil infrastructure—A review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 117, 105478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105478 (2023).

Luo, J., Lin, H., Wei, X. & Wang, Y. Adaptive canny and semantic segmentation networks based on feature fusion for road crack detection. IEEE Access 11, 51740–51753. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3279888 (2023).

Zhu, X. Detection and recognition of concrete cracks on building surface based on machine vision. Prog. Artif. Intell. 11, 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13748-021-00265-z (2022).

Ren, W. & Zhong, Z. Building construction crack detection with BCCD YOLO enhanced feature fusion and attention mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 15, 23167. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05665-y (2025).

Tang, W., Wu, Z., Wang, W., Pan, Y. & Gan, W. VM-UNet++ research on crack image segmentation based on improved VM-UNet. Sci. Rep. 15, 8938. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92994-7 (2025).

Zhang, Z. et al. Algorithm for pixel-level concrete pavement crack segmentation based on an improved U-Net model. Sci. Rep. 15, 6553. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91352-x (2025).

Qu, Z., Mu, G. & Yuan, B. A lightweight network with dual encoder and cross feature fusion for cement pavement crack detection. CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2024.048175 (2024).

Quan, J., Ge, B. & Wang, M. CrackViT: a unified CNN-transformer model for pixel-level crack extraction. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 10957–10973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-023-08277-7 (2023).

Yang, S., Wang, Y. & Chen, H. Mambamil: Enhancing long sequence modeling with sequence reordering in computational pathology. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, 296–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-72083-3_28 (2024).

Pei, X., Huang, T. & Xu, C. Efficientvmamba: Atrous selective scan for light weight visual mamba. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 39, 6443–6451. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v39i6.32690 (2025).

Liao, W. et al. Lightm-unet: Mamba assists in lightweight unet for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2024. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.05246.https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.05246 (2024).

Bansal, S. et al. A comprehensive survey of mamba architectures for medical image analysis: Classification, segmentation, restoration and beyond. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.02362.https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.02362 (2024).

Iriawan, N. et al. YOLO-UNet architecture for detecting and segmenting the localized MRI brain tumor image. Appl. Comput. Intell. Soft Comput. 2024, 3819801. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/3819801 (2024).

Guo, Q., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhao, M. & Jiang, Y. AIE-YOLO: Effective object detection method in extreme driving scenarios via adaptive image enhancement. Sci. Prog. 107, 00368504241263165. https://doi.org/10.1177/00368504241263165 (2024).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5–9, 2015, proceedings, part III 18. (Springer, 234–241). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-54345-0_3.

Zhou, Z., Siddiquee, M. M. R., Tajbakhsh, N. & Liang, J. Unet++: Redesigning skip connections to exploit multiscale features in image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39, 1856–1867. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2019.2959609 (2019).

Zou, Q. et al. Deepcrack: Learning hierarchical convolutional features for crack detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 28, 1498–1512. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2018.2878966 (2018).

Pan, Z., Lau, S. L., Yang, X., Guo, N. & Wang, X. Automatic pavement crack segmentation using a generative adversarial network (GAN)-based convolutional neural network. Results Eng. 19, 101267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101267 (2023).

Yu, G., Dong, J., Wang, Y. & Zhou, X. RUC-Net: A residual-Unet-based convolutional neural network for pixel-level pavement crack segmentation. Sensors 23, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23010053 (2022).

Chen, W., Mu, Q. & Qi, J. TrUNet: Dual-branch network by fusing CNN and transformer for skin lesion segmentation. IEEE Access. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3463713 (2024).

Wang, W. & Su, C. Automatic concrete crack segmentation model based on transformer. Autom. Constr. 139, 104275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104275 (2022).

Liu, C., Zhu, C., Xia, X., Zhao, J. & Long, H. FFEDN: Feature fusion encoder decoder network for crack detection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 15546–15557. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2022.3141827 (2022).

Liu, H., Miao, X., Mertz, C., Xu, C. & Kong, H. Crackformer: Transformer network for fine-grained crack detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (3783–3792). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00376 (2021).

Liu, H., Yang, J., Miao, X., Mertz, C. & Kong, H. CrackFormer network for pavement crack segmentation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24, 9240–9252. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2023.3266776 (2023).

Wu, H. et al. FAT-Net: Feature adaptive transformers for automated skin lesion segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 76, 102327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2021.102327 (2022).

Xiang, C., Guo, J., Cao, R. & Deng, L. A crack-segmentation algorithm fusing transformers and convolutional neural networks for complex detection scenarios. Autom. Constr. 152, 104894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2023.104894 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. Dual attention transformer network for pixel-level concrete crack segmentation considering camera placement. Autom. Constr. 157, 105166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2023.105166 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. TransUNet: Rethinking the U-Net architecture design for medical image segmentation through the lens of transformers. Med. Image Anal. 97, 103280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2024.103280 (2024).

Wang, C., Liu, H., An, X., Gong, Z. & Deng, F. SwinCrack: Pavement crack detection using convolutional swin-transformer network. Digit. Signal Process. 145, 104297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsp.2023.104297 (2024).

Wang, Z., Zheng, J., Zhang, Y., Cui, G. & Li, L. Mamba-unet: Unet-like pure visual mamba for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2024. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.05079. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.05079 (2024).

Ruan, J., Li, J. & Xiang, S. Vm-unet: Vision mamba unet for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.02491. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.02491 (2024).

Liu, X., Zhang, C. & Zhang, L. Vision mamba: A comprehensive survey and taxonomy. arXiv 2024. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.04404. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.04404 (2024).

Wang, J., Chen, J., Chen, D. & Wu, J. LKM-UNet: Large kernel vision mamba unet for medical image segmentation. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (360–370). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-72111-3_34 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. Swin-umamba: Mamba-based unet with imagenet-based pretraining. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (615–625). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-72114-4_59 (2024).

Chen, Z., Shamsabadi, E. A., Jiang, S., Shen, L. & Dias-da-Costa, D. Vision Mamba-based autonomous crack segmentation on concrete, asphalt, and masonry surfaces. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.16518. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2406.16518 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Vmamba: Visual state space model. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 37, 103031–103063 (2024).

Lu, L., Yin, M., Fu, L. & Yang, F. Uncertainty-aware pseudo-label and consistency for semi-supervised medical image segmentation. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 79, 104203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2022.104203 (2023).

Li, H., Nan, Y., Del Ser, J. & Yang, G. Region-based evidential deep learning to quantify uncertainty and improve robustness of brain tumor segmentation. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 22071–22085. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-022-08016-4 (2023).

Zhou, B., Khosla, A., Lapedriza, A., Oliva, A. & Torralba, A. Learning deep features for discriminative localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2921–2929). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.319 (2016).

Yang, F. et al. Feature pyramid and hierarchical boosting network for pavement crack detection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 21, 1525–1535. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2019.2910595 (2019).

Zou, Q., Cao, Y., Li, Q., Mao, Q. & Wang, S. CrackTree: Automatic crack detection from pavement images. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 33, 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2011.11.004 (2012).

Shi, Y., Cui, L., Qi, Z., Meng, F. & Chen, Z. Automatic road crack detection using random structured forests. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 17, 3434–3445. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2016.2552248 (2016).

Ma, J., Li, F. & Wang, B. U-mamba: Enhancing long-range dependency for biomedical image segmentation. arXiv 2024. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.04722. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.04722 (2024).

Funding

This research was funded by Pilot Project for Building a Country with Strong Transportation Network of Research Institute of Highway, Ministry of Transport (grant number QG 2021-3-15-5), Key Science and Technology Project of the Transportation Industry (grant number 2021-ZD1-032).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J. and Y.W. mainly proposed the concept and methods. Y.W. and Z.W. were responsible for the algorithm implementation. J.J., L.Z., and X.C. verified the overall content. X.C. and Z.W. preprocessed the experimental data. Y.W. was responsible for writing, editing, and reviewing the draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Jin, J., Chen, X. et al. A lightweight crack segmentation network based on the importance-enhanced Mamba model. Sci Rep 15, 41549 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25504-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25504-4