Abstract

Cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum [CDDP]) is a widely used anticancer drug with a significant risk of nephrotoxicity. This study aimed to compare the nephroprotective effects of mannitol and furosemide as forced diuretics in patients receiving CDDP-based chemotherapy. This multicenter retrospective study analyzed 472 patients with cancer receiving CDDP (≥ 60 mg/m2) with either mannitol or furosemide as forced diuretics. Patient characteristics were balanced using inverse probability treatment weighting. Nephrotoxicity was assessed using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (ver. 5.0) criteria. The results showed that the incidence of nephrotoxicity was significantly lower in the furosemide group than in the mannitol group (6.2% vs. 23.2%, p < 0.007). The mean serum creatinine increase was significantly lower with furosemide (21.7% ± 19.3%) than with mannitol (29.5% ± 40.7%, p = 0.007). Hypertension, cisplatin dose ≥ 75 mg/m2, absence of magnesium supplementation, and mannitol use were associated with a higher risk of nephrotoxicity. Stratified analysis demonstrated furosemide’s superior nephroprotective effects regardless of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. Thus, furosemide was associated with superior renoprotective effects compared with mannitol in CDDP-based chemotherapy regimens, thereby making it a viable therapeutic alternative to mannitol. Large randomized controlled trials are warranted to further validate our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum [CDDP]) is a platinum-containing agent and an effective anticancer drug for a wide range of solid tumors that inhibits DNA replication by forming DNA cross-links. Numerous serious adverse effects of CDDP have been reported, including nephrotoxicity, bone marrow suppression, hearing loss, tinnitus, and nausea/vomiting1,2. Specifically, CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity necessitates discontinuation or dose reduction of CDDP and significantly impacts subsequent drug therapies1,2. A factor contributing to CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity is that CDDP is excreted from the kidneys via both glomerular filtration and tubular secretion, resulting in CDDP concentrations in the kidneys exceeding blood levels and accumulation in renal parenchymal cells3,4. Additionally, some unbound CDDP that is not filtered by the glomeruli may be excreted from the kidneys through tubular secretion5. During this process, CDDP is actively transported into cells via the organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2), which accumulates in tubular epithelial cells and causes tubular necrosis3,6. The main methods used to prevent CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity include hydration, diuretic administration, and magnesium (Mg) supplementation7,8,9,10,11,12. Importantly, hydration and diuretics are thought to mitigate renal injury by increasing urine output, thereby diluting CDDP concentration within the kidneys7,8, while Mg supplementation addresses hypomagnesemia, which is a common side effect of CDDP13. Hypomagnesemia reportedly upregulates OCT2 expression, potentially increasing renal CDDP accumulation and exacerbating nephrotoxicity14.

The diuretics currently used in clinical practice are the osmotic diuretic mannitol and loop diuretic furosemide7. Mannitol reportedly exerts protective effects against nephrotoxicity in vivo2,15. Additionally, furosemide prevents CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity, and in vivo studies evaluating renal function via blood urea nitrogen have reported that the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is partially preserved in rats administered furosemide16,17. Although the preventive effect of diuretics on nephrotoxicity has been reported, evidence regarding the relationship between diuretic type and nephroprotective effects is insufficient, and an appropriate type of diuretic for preventing nephrotoxicity has not been established. Several previous studies comparing mannitol and furosemide have been published16,18,19,20; however, the results were derived using small sample sizes and are not conclusive regarding their superiority in preventing nephrotoxicity. Here, we examined the effects of mannitol and furosemide on the prevention of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in a relatively large cohort of patients with adjustments for patient characteristics using inverse probability treatment weighting (IPTW), albeit in a retrospective analysis.

Methods

Setting and patients

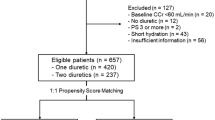

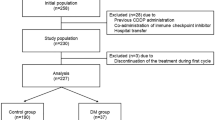

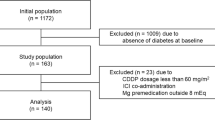

We analyzed patient-level pooled data from a multicenter, retrospective observational study21. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions and by the Ethics Committee of Beppu Medical Center (approval No. 2016-011). All participants were treated in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of Beppu Medical Center, the coordinating center, waived the requirement for informed consent owing to the retrospective nature of the study. Patient data were used after allowing patients to refuse to participate using an opt-out form. We analyzed 472 cancer patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0–2 and creatinine clearance of ≥ 60 mL/min who received CDDP (≥ 60 mg/m2) for the first time and were administered furosemide (20 mg) and/or mannitol (20% 300 mL) as forced diuretics along with conventional high-volume hydration per cycle. Patients treated with the short hydration method were excluded to ensure comparable hydration conditions for evaluating the effects of the diuretics.

Data collection

Data on the following patient characteristics were collected: Mg supplementation, sex, age, ECOG PS, presence of cardiac disease, presence of diabetes, presence of hypertension, chemotherapy regimen, CDDP dose, regular use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), diuretic type, number of chemotherapy courses administered, serum creatinine (SCr) level, occurrence of renal failure, and Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) ver. 5.0 grade. Cardiac disease was defined as angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, arrhythmia, or valvular disease. SCr was measured using an enzymatic method at least 2 weeks after the start of CDDP administration and was used to determine the presence of nephrotoxicity. Based on the CTCAE ver. 5.0 grades for creatinine elevation, the development of nephrotoxicity was defined as an increase in the SCr after CDDP administration of at least one grade higher than that before CDDP administration. All patients received conventional high-volume hydration, and none of them received short hydration. The exclusion ensured a more homogeneous hydration context for evaluating diuretic strategies.

Statistical analysis

We used an IPTW model derived from a logistic regression model to balance observable characteristics among the administered diuretics (covariates: age, male sex, cardiac disease, diabetes, hypertension, albumin level, CDDP dose, Mg supplementation, regular use of NSAIDs, ECOG PS, and cycle of chemotherapy). Inclusion of variables in the model was based on existing knowledge of risk factors for nephrotoxicity and the literature21,22,23,24. The cutoff values for age (63 years), albumin level (3.9 g/L) and cisplatin dose (75 mg/m2) were based on a previous study21. The incidence of nephrotoxicity was compared between the mannitol and furosemide groups using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Chi-square test. Analysis of covariance, with baseline values as covariates, was performed compare the rate of change in SCr. The rates of SCr change were calculated using the following formula:

(maximum SCr - baseline SCr) × 100/baseline SCr.

Additionally, to assess risk factors for nephrotoxicity, we performed a multivariate logistic regression using backward elimination method, adjusting for potential confounding by age, sex, albumin level, diabetes, hypertension, cardiac disease, Mg supplementation, regular use of NSAIDs, CDDP dose, and cycle of chemotherapy. The selection of variables for inclusion in the model was determined a priori, based on the existing literature and their clinical relevance.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-sided). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

We included 472 patients receiving CDDP in this analysis. The types of cancer in the study population are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Baseline characteristics, including sex, age, albumin level, cardiac disease, hypertension, diabetes, ECOG PS, CDDP dose, Mg supplementation, NSAID use, and chemotherapy cycle, are presented in Table 1, listing the unadjusted and adjusted patient characteristics stratified by mannitol or furosemide. The visual plot for the balance diagnostics of IPTW is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. However, an imbalance in NSAID use was observed.

Severity of nephrotoxicity

The severity grades of nephrotoxicity (CTCAE v5) in each group after IPTW adjustment are presented in Table 2. We compared the severity grades of nephrotoxicity between patients treated with mannitol (n = 246) and furosemide (n = 244). The Wilcoxon rank-sum test revealed a statistically significant difference in the distribution of nephrotoxicity severity grades between the two groups (p < 0.001).

Changes in SCr in all subsequent cycles

The mean rates of SCr change of the mannitol and furosemide groups were 29.5 ± 40.7 and 21.7 ± 19.3 mg/dL, respectively, with a significant difference in the rate of change in SCr between the two groups (p = 0.007) (Table 3).

Risk factors for CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity

The results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses of the risk factors for nephrotoxicity are shown in Table 4. Presence of hypertension (p = 0.017), CDDP dose ≥ 75 mg/m2 (p = 0.005), no Mg supplementation (p < 0.001), and mannitol use (p < 0.001) were associated with a higher risk of nephrotoxicity.

Stratified analysis

A stratified analysis of the incidence of nephrotoxicity was performed by comparing the mannitol and furosemide groups by each risk factor after IPTW adjustment. Among NSAID users, the data showed a significantly higher sum of scores in the mannitol group than in the furosemide group (p < 0.001). Similarly, among NSAID non-users, the mannitol group showed a significantly higher sum of scores than did the furosemide group (p = 0.090). These findings suggest that, after adjusting for patient backgrounds, outcomes in the mannitol group were significantly higher than those in the furosemide group, regardless of NSAID use (Table 5). Furthermore, in a multivariate analysis stratified by NSAID use (yes/no), conducted as a sensitivity analysis, mannitol use was identified as a factor associated with the occurrence of nephrotoxicity, irrespective of NSAID use (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

Herein, we compared the protective effects of mannitol and furosemide on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. The incidence of nephrotoxicity was 23.2% in the mannitol group and 6.2% in the furosemide group, with a significant difference observed (p < 0.007). Additionally, the incidence of Grade ≥ 2 nephrotoxicity was 2.8% in the mannitol group and 0.2% in the furosemide group. The presence of hypertension, CDDP dose ≥ 75 mg/m2, absence of Mg administration, and mannitol use were associated with a higher risk of nephrotoxicity. Notably, mannitol use has been identified as a risk factor for CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity, along with the following well-known risk factors: hypertension21,25, high CDDP dose21,26, and absence of Mg supplementation9,21,27. Our study cohort exhibited a non-negligible imbalance regarding the regular use of NSAIDs, which have been reported to worsen nephrotoxicity24,27. Therefore, we conducted a stratified analysis based on NSAID usage. The results demonstrated that the furosemide group showed significantly better preventive effects against nephrotoxicity regardless of whether NSAIDs were used or not. Furthermore, consistent results were observed in a multivariate analysis stratified by NSAID use (yes/no), which was conducted as a sensitivity analysis. Loop diuretics can decrease effective circulating volume and, in combination with NSAIDs, may increase the risk of prerenal acute kidney injury (AKI) because NSAID-mediated cyclooxygenase inhibition reduces prostaglandin-dependent afferent arteriolar vasodilation and can blunt the natriuretic effect of furosemide. However, in our IPTW-adjusted stratified analysis by NSAID use, furosemide was associated with significantly lower nephrotoxicity than mannitol among both NSAID users and non-users, suggesting that the observed benefit of furosemide is unlikely to be driven by an NSAID–furosemide interaction. Nonetheless, residual confounding cannot be excluded, and future prospective trials should pre-specify interaction analyses for NSAID exposure. Additionally, among female patients, patients with cardiac disease, those with hypertension, and those who received fewer than three cycles of chemotherapy, the mannitol group tended to have a lower incidence of nephrotoxicity. However, across all other strata, the furosemide group exhibited a lower incidence of nephrotoxicity, consistent with the overall findings. Although there is limited evidence for a direct potentiation of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by furosemide, it can reportedly pose an indirect risk through the deterioration of hemodynamic status in patients having cancer with comorbid cardiac disease28. The findings suggest that furosemide may pose a potential risk in patients with cardiac disease, which should be clarified in future research. Furthermore, the subgroups of female sex, patients with cardiac disease, patients with hypertension, and those with fewer than three chemotherapy cycles had very small sample sizes, which may have influenced these results.

The nephrotoxicity observed in this study was predominantly Grade 1 and was generally manageable with supportive care and dose modification. While statistically significant, the clinical relevance of this predominantly mild toxicity may be limited at the individual patient level. Nevertheless, even Grade 1 declines in renal function can accumulate over successive treatment cycles, potentially constraining the cumulative cisplatin dose. Therefore, we recommend caution against overinterpretation of these results and underscore the need for an individualized risk–benefit assessment for each patient.

Previous studies have compared mannitol and furosemide for cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity prevention. A small randomized controlled trial found no significant difference in nephrotoxicity incidence between mannitol and furosemide groups16. However, the furosemide group showed greater urine output at 1 h post-administration, with lower rates of unplanned furosemide administration, fluid loading, and vomiting, but higher incidence of hyponatremia compared to the mannitol group16. A retrospective observational study comparing the nephroprotective effects of mannitol and furosemide with low-dose cisplatin (40 mg/m2) reported no significant differences in SCr changes or hypomagnesemia incidence between groups19. Furthermore, a small randomized controlled trial comparing normal saline, mannitol, and furosemide showed significant differences in decreased 24-h creatinine clearance between the normal saline group and the mannitol group, and between the furosemide group and the mannitol group, suggesting that furosemide and normal saline provided superior nephroprotection compared to mannitol29.

A single-center, open-label, randomized phase II study demonstrated that although mannitol is the standard diuretic in CDDP-based chemotherapy according to conventional CTCAE grading, furosemide can also be considered when assessed by actual SCr level and Cr clearance18. Additionally, mannitol may cause phlebitis, which adversely affects patients’ quality of life. Although the difference was not statistically significant, the incidence of phlebitis was 1.7 times higher in the mannitol arm18.

Furosemide inhibits Na–K–Cl cotransporter 2 in the thick ascending limb, reducing tubular sodium reabsorption and medullary oxygen demand, potentially mitigating ischemic susceptibility during cisplatin exposure30. Altered tubular chloride handling may influence cisplatin aquation kinetics and cellular uptake26,31. Additionally, diuretic-induced changes in luminal flow and sodium delivery can modulate expression/activity of transporters implicated in cisplatin handling (e.g., OCT2, copper transporter 1, multidrug and toxin extrusion 1/2-K) and reduce contact time with proximal tubular cells4,6,32. In contrast, mannitol’s osmotic diuresis may transiently raise intratubular pressure and, in the presence of tubular injury, potentially promote back-leak without directly modulating transporter activity33. These mechanisms could plausibly contribute beyond urine output alone.

Considering the convenience of furosemide administration, furosemide may also be considered in CDDP-based chemotherapy owing to similar serum Cr changes, lower skin toxicity, shorter administration time, and simplicity of the procedure. The optimal choice for individual patients should be made after comprehensively evaluating not only renoprotective effects but also patient characteristics, side effect profiles, feasibility, cost, and other factors.

This study had some limitations. First, it was a retrospective observational study rather than a randomized or prospective study. Despite IPTW and multiple sensitivity analyses, residual and unmeasured confounding cannot be eliminated in this non-randomized design, and the results should be interpreted with caution. Second, individual quantifiable data on heart disease (e.g., cardiac output and ejection fraction) were not available; therefore, heart disease was defined solely based on a history of heart disease, such as angina pectoris or myocardial infarction. Third, data on serum Mg levels, blood glucose and blood pressure, urine dipsticks for hematuria or proteinuria, and urine volume were unavailable, and adjustment for the timing of blood creatinine measurement was not possible due to the observational nature of the study. Fourth, data on potential risk factors, including the use of aminoglycosides, metformin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin II receptor blockers, were not at our disposal. Fifth, the safety profile could not be determined in this pooled analysis because adverse event data were not recorded in the medical records. Sixth, clinical testing was conducted in all cases immediately before each chemotherapy cycle, whereas testing during the treatment cycle varied among cases. Consequently, the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria for AKI could not be used to assess nephrotoxicity in this study. Moreover, eGFR was not used as an outcome measure. Although eGFR is an informative renal function metric, the retrospective design limited our ability to consistently capture all variables necessary for accurate eGFR computation (e.g., body weight contemporary with each creatinine measurement) across all patients. Although we recognize the importance of the KDIGO criteria or eGFR in assessing the details of the development of renal injury, the CTCAE is a standard measure of chemotherapy-induced toxicity in clinical oncology, and we believe it has some relevance in this study. We adopted CTCAE grading as the primary endpoint on the basis of a previous study; however, future studies to assess CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity should pay more attention to this point. Finally, the inclusion of only conventional high-volume hydration and not the short hydration method as a method to prevent nephrotoxicity other than forced diuresis limits the generalizability of the study results. Furthermore, since this study was limited to a high-dose, single-day cisplatin regimen, further investigation is required to determine the applicability of these findings to other malignancies or alternative administration protocols, such as fractionated multi-day schedules. The findings of this study should also be considered in the context of our patient cohort, which primarily consisted of patients with head and neck cancer, esophageal cancer, and lung cancer.

Despite the limitations, our multicenter sample size was relatively large compared with prior single-center studies, thereby improving statistical precision and increased the potential for application across diverse clinical settings. In this retrospective analysis, furosemide was associated with improved renoprotection, suggesting that it may be a viable therapeutic option. Nevertheless, confirmatory evidence from larger randomized controlled trials is warranted.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the study group. However, restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under a license for the current study and are thus not publicly available. Data is, nevertheless, available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the study group.

Abbreviations

- Alb:

-

Albumin

- CDDP:

-

Cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (cisplatin)

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- Cr:

-

Creatinine

- CTCAE:

-

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- ECOG PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status

- IPTW:

-

Inverse probability treatment weighting

- KDIGO:

-

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

- Mg:

-

Magnesium

- NSAIDs:

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- OCT2:

-

Organic cation transporter 2

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SCr:

-

Serum creatinine

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

References

Hartmann, J. T. & Lipp, H. P. Toxicity of platinum compounds. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 4, 889–901 (2003).

Wensing, K. U. & Ciarimboli, G. Saving ears and kidneys from cisplatin. Anticancer Res. 33, 4183–4188 (2013).

Yao, X., Panichpisal, K., Kurtzman, N. & Nugent, K. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: A review. Am. J. Med. Sci. 334, 115–124 (2007).

Pabla, N. & Dong, Z. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: Mechanisms and renoprotective strategies. Kidney Int. 73, 994–1007 (2008).

Nagai, N. & Ogata, H. Quantitative relationship between pharmacokinetics of unchanged cisplatin and nephrotoxicity in rats: Importance of area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) as the major toxicodynamic determinant in vivo. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 40, 11–18 (1997).

Filipski, K. K., Mathijssen, R. H., Mikkelsen, T. S., Schinkel, A. H. & Sparreboom, A. Contribution of organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2) to cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 86, 396–402 (2009).

Crona, D. J. et al. A systematic review of strategies to prevent cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Oncologist 22, 609–619 (2017).

Pinzani, V. et al. Cisplatin-induced renal toxicity and toxicity-modulating strategies: A review. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 35, 1–9 (1994).

Saito, Y. et al. Premedication with intravenous magnesium has a protective effect against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Support Care Cancer 25, 481–487 (2017).

Hase, T. et al. Short hydration with 20 mEq of magnesium supplementation for lung cancer patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy: A prospective study. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 1928–1935 (2020).

Miyoshi, T. et al. Preventive effect of 20 mEq and 8 mEq magnesium supplementation on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity: A propensity score–matched analysis. Support Care Cancer 30, 3345–3351 (2022).

Takagi, A. et al. Comparison of preventive effects of combined Furosemide and mannitol versus single diuretics, Furosemide or mannitol, on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Sci. Rep. 14, 10511 (2024).

Vickers, A. E. M. et al. Kidney slices of human and rat to characterize cisplatin-induced injury on cellular pathways and morphology. Toxicol. Pathol. 32, 577–590 (2004).

Yokoo, K. et al. Enhanced renal accumulation of cisplatin via renal organic cation transporter deteriorates acute kidney injury in hypomagnesemic rats. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 13, 578–584 (2009).

Bégin, A. M. et al. Effect of mannitol on acute kidney injury induced by cisplatin. Support Care Cancer 29, 2083–2091 (2021).

Makimoto, G. et al. Randomized study comparing mannitol with Furosemide for the prevention of cisplatin-induced renal toxicity in non-small cell lung cancer: The OLCSG1406 trial. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 17, 101–108 (2021).

El Hamamsy, M., Kamal, N., Bazan, N. S. & El Haddad, M. Evaluation of the effect of Acetazolamide versus mannitol on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity, a pilot study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 40, 1539–1547 (2018).

Murakami, E. et al. Mannitol versus Furosemide in patients with thoracic malignancies who received cisplatin-based chemotherapy using short hydration: A randomized phase II trial. Cancer Med. 13, e6839 (2024).

Mach, C. M. et al. A retrospective evaluation of Furosemide and mannitol for prevention of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 42, 286–291 (2017).

Ostrow, S. et al. High-dose cisplatin therapy using mannitol versus furosemide diuresis: Comparative pharmacokinetics and toxicity. Cancer Treat. Rep. 65, 73–78 (1981).

Miyoshi, T. et al. Cisplatin-Induced nephrotoxicity: A multicenter retrospective study. Oncology 99, 105–113 (2021).

Motwani, S. S. et al. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for acute kidney injury after the first course of cisplatin. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 682–688 (2018).

Mizuno, T. et al. The risk factors of severe acute kidney injury induced by cisplatin. Oncology 85, 364–369 (2013).

Kidera, Y. et al. Risk factors for cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and potential of magnesium supplementation for renal protection. PLOS One 9, e101902 (2014).

Saito, Y. et al. Risk factor analysis for cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity with the short hydration method in diabetic patients. Sci. Rep. 13, 17126 (2023).

Miller, R. P., Tadagavadi, R. K., Ramesh, G. & Reeves, W. B. Mechanisms of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Toxins 2, 2490–2518 (2010).

Yoshida, T. et al. Protective effect of magnesium preloading on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity: A retrospective study. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 44, 346–354 (2014).

Ronco, C. et al. Cardiorenal syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 52, 1527–1539 (2008).

Santoso, J. T., Lucci, J. A., Coleman, R. L., Schafer, I. & Hannigan, E. V. Saline, mannitol, and Furosemide hydration in acute cisplatin nephrotoxicity: A randomized trial. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 52, 13–18 (2003).

Evans, R. G. et al. Haemodynamic influences on kidney oxygenation: clinical implications of integrative physiology. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 40, 106–122 (2013).

Kelland, L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 573–584 (2007).

Ciarimboli, G. et al. Organic cation transporter 2 mediates cisplatin-induced oto- and nephrotoxicity and is a target for protective interventions. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 1169–1180 (2010).

Better, O. S. et al. Mannitol therapy revisited (1940–1997). Kidney Int. 52, 886–894 (1997).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Miyuki Uoi, Fuyuki Ohmura, Sachi Maesaki, Kyouichi Tsumagari, and Chiaki Yokota for providing support as the investigators of the multicenter observational study that collected the data used in this study. We also thank all the participants in the study and their families.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.H. conceptualized the study. T.H., Y.H., and M.S. analyzed the claims data. MS performed the statistical analyses. T.H., M.S., Y.H., T.M., and T.E. contributed to the interpretation of data and assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. Y.H., T.H., and M.S. prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. Y.H., T.H., M.S., A.Y., M.U., S.U., C.S., T.M., K.M., and T.E. conducted the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Harimitsu, Y., Hayashi, T., Shimokawa, M. et al. Mannitol versus furosemide for prevention of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 41537 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25510-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25510-6